Health Risks of Wildfire Smoke: New Study Insights

As I write this nearly 340,000 acres are on fire in the US, with new, large fires reported in Alaska, Idaho, and California. Smoke from those and other recent wildfires move on the wind to areas far away from the actual fires, making a large number of people breathing the smoke.

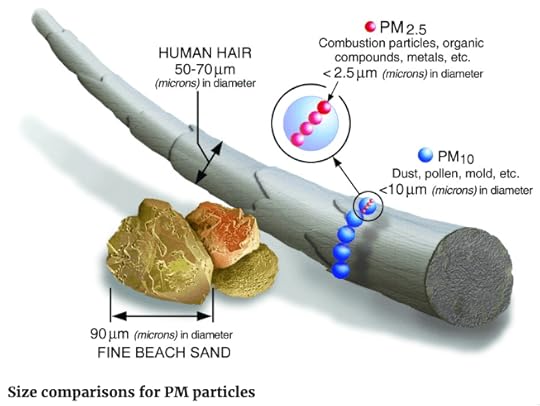

After the many California fires in 2020 more than 36,000 people died from breathing in large amounts of ultrafine particles. Those particles, called PM2.5, are smaller than 2.5 microns in size and are particularly harmful for people with asthma, heart conditions, and the elderly.

Exactly how those particles damaged the body isn’t well understood yet. “We’re in the preschool stage of development,” said environmental epidemiologist Joan Casey of the University of Washington. Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke remains largely unknown.

New StudyBut a new study by researchers at the University of Montana is providing some clues. Immunologist Christopher Migliaccio jumped at the chance to study the health effects of smoke after a 2017 wildfire near Seeley Lake, northwest of Helena. Residents on and near the lake suffered 49 days of smoke-filled air.

Migliaacio and his team studied 95 residents over time and discovered that 10 percent were suffering from diminished lung function right after the fire. That percentage jumped to 46 percent a year later, indicating that health effects take longer to appear than first thought.

Literally toxic airOne of the issues scientists face in understanding wildfire smoke concerns non-organic toxins in the smoke. The Paradise fire last year, for instance, consumed not just forested land but homes, cars, trucks, paints, appliances, electronics, flooring, insulation, water pipes, and many other manmade materials. Toxins released from those items include:

Toxic gases, called volatile organic compounds or VOCsCarbon monoxideNitrogen oxidesLead, zinc, chromium, and other heavy compounds from the burning of vehiclesAsbestosDioxinThe Donora Death Fog happened more than 75 years ago, and still we don’t know as much as we should about the devastating health effects of wildfire smoke. The Clean Air Act, initiated after the Donora disaster, treats wildfire as an “exceptional event,” and so leaves it without regulation.

With wildfires becoming more common, especially in the West, and significant industry-fueled air pollution continuing in many parts of the country, the nation can’t afford any more rollbacks of environmental safeguards. Fight back NOW, before it’s too late.