Figma - The untold story

Reshuffle is now available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle formats.

Both paperback and hardcover are now available in India as well.

Figma has had quite a ride in recent years, from Adobe’s acquisition attempt and regulatory scrutiny to a massive IPO followed by a quick reality check.

Crashing the gates of a well-defended incumbent is one thing. Getting them to pay a premium for you, and eventually getting investors to shower you with an even higher premium and devalue the incumbent in the process - that’s no joke.

Figma’s success is often explained with familiar reasons: it enabled real-time collaboration, grew through strong network effects, delivered great user experience, and cracked enterprise adoption.

All of that is true. But if those really are the factors that explain its success, why couldn’t Adobe, with its resources and dominance, simply do the same?

Adobe had the talent, the cash, and the incentive. Collaboration isn’t a deep trade secret, and enterprise distribution is Adobe’s home turf.

The answers to this question, again, circle back to well-worn tropes

Incumbents are slow, startups move fast.

Ideas are cheap, execution is the differentiator.

These explanations are, in a phrase - true, but utterly useless - and examples of what I’ve previously called consensus theater.

The problem with consensus theater is that the topic ends right there. Everyone leaves the room feeling smart, yet not a single person has a clue on how to apply this newly acquired insight the right way.

So the real answer must lie somewhere deeper.

This is the untold story of Figma.

First time here? Sign up now.

Figma - the well-worn story

Figma - the well-worn story If you’re not entirely familiar with Figma, let’s first start with the well-worn story used to explain Figma’s success.

Figma is a cloud-hosted design tool that allows multiple people to design, comment, and iterate on the same design project.

Figma saw that design isn’t only about designers, but about how entire teams collaborate around the design workflow. Designers, product managers, engineers, even execs. Unlike traditional design software, it treats design as a collaborative, multiplayer activity rather than a solo task.

That shift from individual productivity to organizational collaboration created Figma’s advantage by driving virality and network effects within and across teams.

The more designers used Figma, the more they pulled in non-designers. And the more non-designers used it, the more value it had for designers as feedback got faster and decisions were made sooner. This became Figma’s compounding engine, as its usage expanded across entire companies and across networks of collaborators.

This ‘collaboration drove network effects’ story is the well-worn story used to explain Figma’s success.

Adobe and Figma - divergence on the cloudBoth Adobe and Figma have built large sucecssful businesses on the cloud. But their approach couldn’t be more different.

Adobe moved from selling a box of software with one‑time licenses to selling subscriptions, but the mental model stayed the same: a powerful tool for a single user. The primary customer, for all purposes, remained the same - the designer.

Instead of merely delivering design software over the cloud, Figma reimagined design from a single-player execution-oriented activity to a multi-player coordination-oriented activity.

All these differences are non-trivial. And execution is important.

But it still doesn’t quite explain why it wasn’t just difficult - but impossible - for Adobe to copy Figma.

The real reason Adobe couldn’t do what Figma did was architecture,

not execution.

Adobe’s software was architected in a world of desktop software. Figma’s software was architected for the cloud.

In other words, Figma is cloud-native, Adobe is not.

That doesn’t mean Adobe didn’t build a business on the cloud. It did - and a very successful one at that. However, it ported the architecture of its desktop business and layered it onto the cloud.

In other words:

Adobe used the cloud as a new distribution channel and a new revenue model. No small feat - and not the sign of a slow-moving incumbent struggling to execute.

So all those tropes used to explain Adobe’s inability to ‘do a Figma’ don’t quite make sense.

Figma, instead, reimagined every aspect of its business around the capabilities of the cloud.

This is where things get interesting.

Let’s dig in.

The ideas used in this deep-dive are explained in my new book Reshuffle.

If you’d like to get daily updates on lessons from Reshuffle, follow me on LinkedIn where I post ideas from the book regularly.

How Figma built a cloud-native businessThe most important difference between Adobe and Figma is the one that is also least understood.

The most important difference is in how the two companies view the very logic of design work.

Adobe's design logic is built around the design file (.psd, .ai) as the atomic unit of work.

Figma’s design logic is built around an element in the design file - a button, icon, or type style - as the atomic unit of work.

This might seem like an insignificant difference but ends up changing the nature of business models each company can support, the stakehodlers it can serve, and even the structure of the larger industry around them as well as the basis on which other industry players collaborate and compete.

Adobe’s shift to the cloudTake Adobe’s file-based architecture.

When Adobe moved its Creative Suite into the cloud, it didn’t rethink its core assumptions about how work happened. Photoshop and Illustrator were still built around the same atomic unit: the file.

Designers opened a PSD, worked in layers, saved, and sent it off, repeating the process every time someone else needed to make edits. Files lived on individual machines, and sharing meant duplication. Each round of revisions spawned new versions, which needed to be tracked and reconciled manually. This file‑centric architecture defined how Adobe’s products and business were structured.

Technically, that approach imposed hard limits. Adobe’s products assumed that a single designer would work on a file at a specific stage in the workflow. Simultaneous collaboration was not possible.

Figma’s shift to the cloudThe cloud introduced four architectural enablers that Adobe’s model didn’t fully exploit.

First, always-on connectivity ensured that design assets could reside on the network, rather than on a hard drive.

As a result, one version of the truth could exist on a server, accessible simultaneously by everyone. This single source of truth enabled collaboration.

Collaboration was further strengthened by moving most of the processing to the cloud, enabling users to collaborate in real-time even if they had low processing power on their devices.

Finally, thanks to an API‑driven architecture, individual design elements could be stored and referenced dynamically, rather than frozen in a single monolithic file.

Figma reimagined all of design work around these four capabilities of the cloud.

It replaced the file with the element - a button, icon, or type style - as the basic unit of work. The ‘design document’ existed only on Figma’s servers. Instead of saving and sending files, users accessed a shared space directly.

Because everything lived in the cloud, Figma reimagined design for collaboration. Multiple stakeholders on a project, such as designers, product managers, and marketers, could be working on the same file simultaneously, seeing changes as they occur, without worrying about whose version is the latest.

Changes and permissions could be tracked and managed at the level of a design element. Each element was addressable in a database: change a component once and that change propagated everywhere it appeared. Permissions replaced ownership; engineers, product managers, and marketers could view or comment without being sent anything.

The shift from ‘file’ to ‘element’ as the atomic unit of work had another important effect. Because of the element-based architecture, Figma users could create shared libraries of reusable design components, like buttons, icons, type styles, and color palettes, that teams could use across multiple files and projects. Instead of duplicating these elements in each file, designers simply reference a single source of truth.

This creates consistency, simplifies updates (change once, update everywhere), and enables cross-functional teams to work with aligned visual standards. Shared libraries shift design from isolated file ownership to coordinated, system-level collaboration.

This architecture created strategic separation from Adobe. Adobe used the cloud to deliver the same file‑based logic more efficiently. Figma used the cloud to replace that logic entirely.

By shifting the unit of work from file to element, Figma enabled real‑time collaboration, created a shared design environment that expanded who could participate, and made Adobe’s model feel increasingly constrained by its own architecture.

Like it so far? Share it further!

How Figma restructured an entire industryThe shift from file to element delivered three critical blows to Adobe.

1. WORK: It broke Adobe’s control over the unit of workFiles reflected individual work, handed off between collaborators in sequential stages. Figma upended this by unbundling the file into its constituent elements.

This unbundling turned design into a live system, rather than a sequence of files.

It enabled co-editing, granular permissions, and instant updates across all design artifacts. The value shifted from discrete deliverables to ongoing coordination.

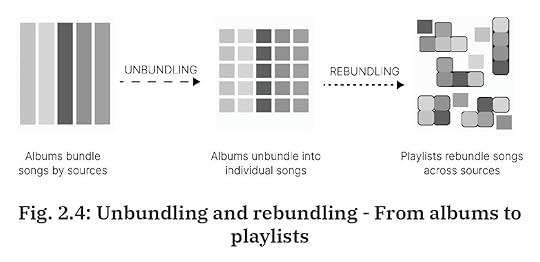

Unbundling changes the unit, which in turn changes architecture. In music, the album was once the atomic unit because the architecture of vinyl and CDs forced songs into bundles. With MP3s, the atomic unit shifted to the song. That simple shift enabled entirely new architectures of distribution: Napster, iTunes, and eventually Spotify.

Image source: Reshuffle

2. ORGANIZATION: It shifted value and power from execution to governanceIn the old world, the unit of value was the act of execution. Who could design faster, deliver cleaner, export assets better.

But with shared elements and real-time updates, execution is commoditized. What matters more is managing permissions, rights, auditability, and collaboration across a multi-player workflow. Governance becomes the new source of leverage.

Design teams can now design coherently at scale. This requires governance: control over how components are created, reused, evolved, and deprecated.

When value shifts from execution to governance, the organizational budgets that pay for your software also change.

In execution-led tools, software is paid for by the teams doing the work - designers, engineers, marketers - because the tool helps them complete specific tasks faster. But in governance-led systems, value comes from managing consistency, control, and coordination across the organization. The budget often shifts upward, because the tool becomes strategic infrastructure, rather than just a productivity aid.

3. INDUSTRY: It eroded Adobe’s closed-loop power and changed industry structureOnce elements were unbundled from the file and individually addressable, they could be packaged into shared libraries, which acted as central sources of truth reused across files and teams.

This restructured the industry from siloed, file-based workflows to interoperable design ecosystems.

When Figma moved design from static files to dynamic elements, it reshaped the structure of the ecosystem. In traditional file-based systems, value was created and captured inside closed loops: files lived on local drives, changes were tracked by humans, and tools were optimized for ownership and execution. The dominant logic was self-contained workflows: a designer edited a file, exported assets, and handed them off, often using proprietary formats inside siloed tools.

But element-level architecture unbundles the design process into modular, reusable pieces. This naturally dissolves the boundary between inside the tool and outside the tool. With components living in shared libraries and third-party tools can plug into atomic design elements through APIs, interoperability was invevitable.

This shift fractured the vertically integrated model Adobe had dominated. Just as the modular web displaced proprietary desktop software, Figma’s architecture enables a loosely coupled, composable ecosystem of tools. integrating at the level of individual design elements. Value no longer accrues to those who own the file, but to those who coordinate the system, through reusable design tokens, shared standards, and governance mechanisms.

So when people say Figma succeeded because of collaboration, they’re not wrong. But they’re also not getting at what really drove Figma’s success.

The real transformation lies in how element-level coordination reshaped the structure of work, the boundaries of the ecosystem, and the source of strategic control.

Applying Figma’s lessons todayFigma delivered three shocks to Adobe’s architecture:

The unit of work changed

The nature of the organizational system changed

The structure of the competitive ecosystem changed

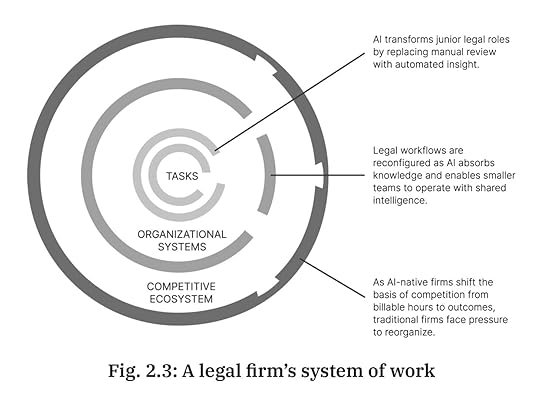

In my book Reshuffle, I explain how the transformative effects of technology play out across the entire system of work:

Consider, for instance, how an AI-native legaltech firm drives changes at all three levels:

Image source: Reshuffle

Much like Figma did with the cloud, companies leveraging AI are poised to trigger a similar structural shift.

Where Figma unbundled the file, AI unbundles today’s human-dominant knowledge workflows into tasks, which can be recombined into fundamentally new workflows.

This eventually changes how work is structured, how workflows and orgs are organized, and how companies compete.

Yet, most players today are doing what Adobe did - they are slapping AI onto the old logic without rearchitecting their business around what AI makes newly possible.

Eventually, you can’t have an ‘AI strategy’

unless you first have an ‘AI-native’ architecture.

That is the untold story of Figma’s success - and that is the lesson that will remain lost on companies that merely interpret Figma as a beneficiary of collaboration software alone.

Get into the weeds with ReshuffleIf you’ve enjoyed reading this post, you should check out my new book Reshuffle.

If you’d like to get daily updates on lessons from Reshuffle, follow me on LinkedIn where I post ideas from the book regularly.