Knowledge Management Thought Leader 127: Hirotaka Takeuchi

Hirotaka Takeuchi is a Professor of Management Practice in the Strategy Unit at Harvard Business School. He co-authored “The New New Product Development Game” which influenced the development of the Scrum framework. His research interests focus on the knowledge creation process within organizations, the competitiveness of Japanese firms in global industries, and the link between strategy and innovation.

In 2016, Takeuchi-san co-founded the Global Academy Corporation. The organization aims to help Japanese businesses reach their full potential by providing both offline and online learning programs to employees of member companies. His early non-academic career included work at McCann-Erickson in Tokyo and San Francisco and at McKinsey & Company in Tokyo.

Here are definitions for five of Takeuchi-san’s specialties:Agile Methodology: A way to manage a project by breaking it up into several phases. It involves constant collaboration with stakeholders and continuous improvement at every stage. Once the work begins, teams cycle through a process of planning, executing, and evaluating. Continuous collaboration is vital, both with team members and project stakeholders. Innovation : The process by which an idea is translated into a good or service for which people will pay. Knowledge Creation : Inventing new concepts, approaches, methods, techniques, products, services, and ideas that can be used for the benefit of people and organizations. Strategy : A set of guiding principles that, when communicated and adopted in the organization, generates a desired pattern of decision making. The way that people throughout the organization should make decisions and allocate resources in order accomplish key objectives. A strategy provides a clear roadmap that defines the actions people should take (and not take) and the things they should prioritize (and not prioritize) to achieve desired goals.Tacit Knowledge: Knowledge that cannot be articulated. It lives in people’s heads and is made up from individual experiences and contexts. It’s not written down and it only comes to the surface when someone asks a question.Takeuchi-san created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about Takeuchi-san, see Profiles in Knowledge.

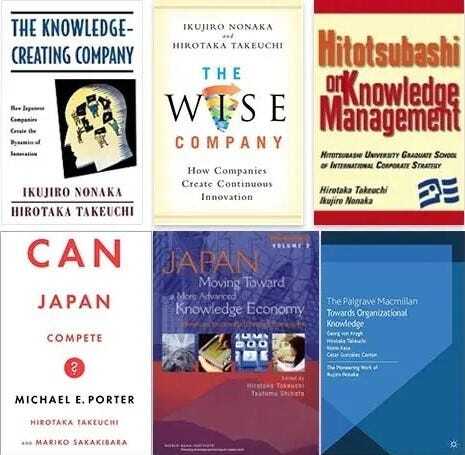

Books

Books The New New Product Development Game

The New New Product Development GameLeading companies show six characteristics in managing their new product development processes:

1. Built-in Instability: Top management kicks off the development process by signaling a broad goal or a general strategic direction. It rarely hands out a clear-cut new product concept or a specific work plan. But it offers a project team a wide measure of freedom and also establishes extremely challenging goals.

2. Self-organizing Project Teams: A project team takes on a self-organizing character as it is driven to a state of “zero information” — where prior knowledge does not apply. Ambiguity and fluctuation abound in this state. Left to stew, the process begins to create its own dynamic order. The project team begins to operate like a start-up company — it takes initiatives and risks, and develops an independent agenda. At some point, the team begins to create its own concept. A group possesses a self-organizing capability when it exhibits three conditions: autonomy, self-transcendence, and cross-fertilization.

Autonomy. Headquarters’ involvement is limited to providing guidance, money, and moral support at the outset. On a day-to-day basis, top management seldom intervenes; the team is free to set its own direction. In a way, top management acts as a venture capitalist.Self-transcendence. The project teams appear to be absorbed in a never-ending quest for “the limit.” Starting with the guidelines set forth by top management, they begin to establish their own goals and keep on elevating them throughout the development process. By pursuing what appear at first to be contradictory goals, they devise ways to override the status quo and make the big discovery.Cross-fertilization. A project team consisting of members with varying functional specializations, thought processes, and behavior patterns carries out new product development. While selecting a diverse team is crucial, it isn’t until the members start to interact that cross-fertilization actually takes place.3. Overlapping Development Phases: The self-organizing character of the team produces a unique dynamic or rhythm. Although the team members start the project with different time horizons — with R&D people having the longest time horizon and production people the shortest — they all must work toward synchronizing their pace to meet deadlines. Also, while the project team starts from “zero information,” each member soon begins to share knowledge about the marketplace and the technical community. As a result, the team begins to work as a unit. At some point, the individual and the whole become inseparable. The individual’s rhythm and the group’s rhythm begin to overlap, creating a whole new pulse. This pulse serves as the driving force and moves the team forward.

4. Multilearning: Because members of the project team stay in close touch with outside sources of information, they can respond quickly to changing market conditions. Team members engage in a continual process of trial and error to narrow down the number of alternatives that they must consider. They also acquire broad knowledge and diverse skills, which help them create a versatile team capable of solving an array of problems fast. Such learning by doing manifests itself along two dimensions: across multiple levels (individual, group, and corporate) and across multiple functions. We refer to these two dimensions of learning as “multilearning.”

5. Subtle Control: Although project teams are largely on their own, they are not uncontrolled. Management establishes enough checkpoints to prevent instability, ambiguity, and tension from turning into chaos. At the same time, management avoids the kind of rigid control that impairs creativity and spontaneity. Instead, the emphasis is on “self-control,” “control through peer pressure,” and “control by love,” which collectively we call “subtle control.” Subtle control is exercised in the new product development process in seven ways:

Selecting the right people for the project team while monitoring shifts in group dynamics and adding or dropping members when necessary.Creating an open work environment.Encouraging engineers to go out into the field and listen to what customers and dealers have to say.Establishing an evaluation and reward system based on group performance.Managing the differences in rhythm throughout the development process. The rhythm is most vigorous in the early phases and tapers off toward the end.Tolerating and anticipating mistakes. The key lies in finding the mistakes early and taking steps to correct them immediately.Encouraging suppliers to become self-organizing. Involving them early during design is a step in the right direction. But the project team should refrain from telling suppliers what to do.6. Transfer of Learning: The drive to accumulate knowledge across levels and functions is only one aspect of learning. We observed an equally strong drive on the part of the project members to transfer their learning to others outside the group. Knowledge is also transmitted in the organization by converting project activities to standard practice. Naturally, companies try to institutionalize the lessons derived from their successes.

To achieve speed and flexibility, companies must manage the product development process differently. Three kinds of changes should be considered.

First, companies need to adopt a management style that can promote the process. Executives must recognize at the outset that product development seldom proceeds in a linear and static manner. It involves an iterative and dynamic process of trial and error. To manage such a process, companies must maintain a highly adaptive style.Second, a different kind of learning is required. Under the traditional approach, a highly competent group of specialists undertakes new product development. An elite group of technical experts does most of the learning. Knowledge is accumulated on an individual basis, within a narrow area of focus — what we call learning in depth. In contrast, under the new approach (in its extreme form) nonexperts undertake product development. They are encouraged to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills on the job. Unlike the experts, who cannot tolerate mistakes even 1% of the time, the nonexperts are willing to challenge the status quo. But to do so, they must accumulate knowledge from across all areas of management, across different levels of the organization, functional specializations, and even organizational boundaries. Such learning in breadth serves as the necessary condition for shared division of labor to function effectively.Third, management should assign a different mission to new product development. Most companies have treated it primarily as a generator of future revenue streams. But in some companies, new product development also acts as a catalyst to bring about change in the organization.From Knowledge to Wisdom (Chapter 1 in The Wise Company: How Companies Create Continuous Innovation)All the knowledge in the world did not prevent the collapse of the global financial system or stop institutions like Lehman Brothers and market leaders like Kodak, General Motors, and Circuit City from failing. All those failures took place at a time when knowledge has become much more abundant, free, limitless, global, open, deeper, and connected, as we mentioned in the Preface. How can that be? The problem, we find, is threefold.

First, we are not harnessing the right kind of knowledge. The two types of knowledge we identified in our first book, The Knowledge- Creating Company, are now well known: explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge. Executives tend to rely on explicit knowledge; it can be codified, measured, and generalized. Wall Street firms believe they can manage greater risk by using numbers, data, analytics, and scientific formulae instead of making judgments about loans one at a time.

The proponents of the market view the world as a test tube, in which variables can be controlled, right down to the conditions in which people live. They work from the premise of a perfectly competitive market, in which every participant has complete information and behaves with complete independence. The same kind of thinking prevails in the US automobile industry, which usually relies on offering financial incentives rather than understanding customer needs.

Dependence on explicit knowledge prevents companies from coping with change. The scientific, deductive, theory- first approach assumes a world independent of context and seeks answers that are universal. However, social phenomena — and that includes business and companies — are context dependent. Analyzing them is meaningless unless people’s subjective goals, values, and interests, as well as the interdependent relationships among them, are considered. Yet, managers fail to do that.

Second, we are not practicing what Peter Drucker espoused, namely, “making” the future. Thanks to scientific discoveries that deal with the environmental, energy, and biodiversity challenges facing the globe, and the technological advances that have helped develop smarter systems, the future is approaching faster than we have imagined.

Managers should be asking themselves: What kind of a future do we want to create? According to our novel inside- out approach to strategy, which we will discuss later in the chapter, companies differ fundamentally because they envision different futures. The specific future that a company’s top management wants to create must be based on subjective goals, beliefs, and interests. People throughout the organization should be aligned around these goals, and should be connected by their social relationships. They should share feelings, emotions, and perspectives with each other, intuitively understand the contexts facing them, and take appropriate actions.

Above all, creating the future must extend beyond the narrow interest of the company. It must be about pursuing the common good. Managers need to ask if decisions are good for society as well as for their companies; management must serve a higher purpose. Only then will companies start thinking of themselves as social entities that have been charged with a mission to create lasting benefits for society. Doing so will also recover the founding agenda of the social sciences, which is to improve the human condition.

Third, we may not be cultivating the right kind of leaders. What a novel, dynamic, and unstable world needs are “wise” leaders who can act as thinking agents of change. Such leaders will make judgments knowing that everything is contextual, will make decisions knowing that everything is changing, and will take actions knowing that everything depends on doing so in a timely fashion. They must see what is good, right, and just for society while being grounded in the details of the ever- changing front lines of business. Thus, they must pair micromanagement with big- picture aspirations about the future.

In addition, the world needs wise leaders who can resist the lure of short- termism and who understand how their companies can operate sustainably. Such leaders realize that no company will survive in the long run unless it creates a future that rivals cannot, offers more value to customers than competitors, lives in harmony with society, has a moral purpose, and pursues the common good as a way of life.

The New Dynamism of the Knowledge-Creating Company (Chapter 1 in Japan, Moving Toward a More Advanced Knowledge Economy — Volume 2: Advanced Knowledge Creating Companies)The Japanese Approach to Knowledge

Views a company as a living organism, rather than as a machineFocuses on justifying belief much more than on seeking truthEmphasizes tacit knowledge over explicit knowledgeRelies on self-organizing teams, not just existing organizational structures, to create new knowledgeTurns to middle managers to resolve contradictions between top management and front-line workersAcquires knowledge from outsiders as well as insidersTo become team leaders in the knowledge economy, middle managers must meet a number of qualifications. They need to be skilled at:

Coming up with hypotheses in order to create mid-range conceptsIntegrating various methodologies for knowledge creationEncouraging dialogue among team membersUsing metaphors and analogies in order to help others generate and articulate imaginationEngendering trust among team membersEnvisioning the future course of action based on an understanding of the pastCoordinating and managing projects.To create a knowledge spiral, a number of different conversions or syntheses need to take place. These include a conversion or synthesis across:

Tacit knowledge and explicit knowledgeLevels (individual, group, and organizational) within the companyFunctions, departments, and divisions within the companyLayers (top-management, middle manager, and front-line worker) within the companyKnowledge inside the company and knowledge outside the company created by suppliers, customers, dealers, local communities, competitors, universities, government and other stakeholdersThese synthesizing capabilities make or break the knowledge creation process.

[image error]