To Sheepscar And Beck

Sheepscar Beck, said Ralph Thoresby, the first historian of Leeds, “is the nameless water, that Mr William Harrison, in his description of Britain, (published in the reign of Queen Elizabeth), mentions as running into the Aire, on the north side of Leeds, from Wettlewood (as it is misprinted for Weetwood), This beck proceeds from a small spring up on the moor, a little above Adel, and yet had some time ago [previous to1714], eight mills upon it, in its four miles’ course. The first is that of Adel near unto which is the Roman camp, and the vestigial of the town lately discovered; and the last before its conjunction with the Aire is this at Sheepscar, which above eighty years ago [before 1714] was employed for the grinding of red wood, and making rape oil, then first known in these parts. It was converted into a corn mill in the late times, but upon the Restoration, when the king’s mills recovered their ancient soke, it dwindled into a paper mill, not for imperial, but for that coarse paper called “emporetica”, useful only for chapmen to wrap wares in. It was afterwards made a rape mill again, as it now stands.”

It’s worth pointing out that Thoresby made an unsuccessful investment in the Sheepscar rape oil mill and lost quite a chunk of his capital.

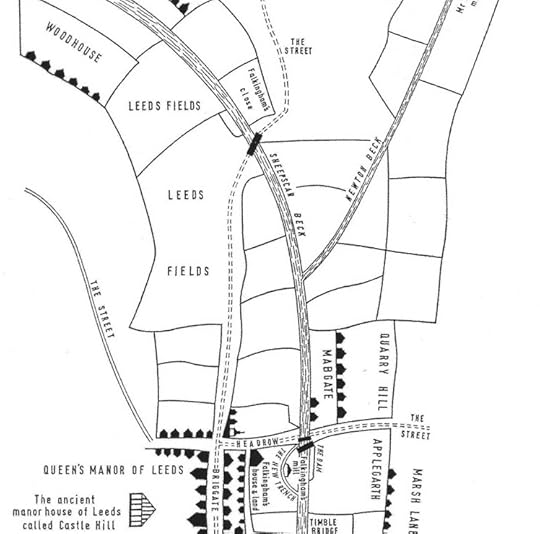

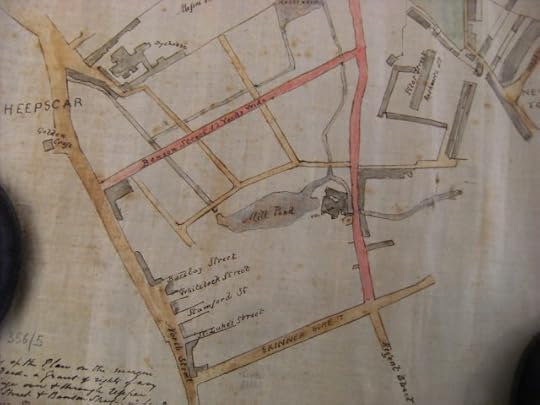

Sheepscar Beck is actually one of two streams that meet near the bottom of the area (along the way it’s also known as Meanwood Beck on its trail across the area from its proper origin on Ilkley Moor). It comes in the from northwest, while Gipton Beck arrives from the north. It’s most clearly illustrated on the most ancient map of Leeds, created for a court case in the 1570s, where Gipton Beck is mysteriously called Newton Beck (the new New Town for part of the area didn’t appear until later).

Together, they become Lady Beck, or Timble Beck, going down Mabgate, then through Leeds (Timble Bridge, covered over more than a century ago, crossed the water at the bottom of Kirkgate) to reach the River Aire close to Crown Point Bridge.

Sheepscar Beck on the left, meets Gipton Beck

Sheepscar Beck on the left, meets Gipton BeckEarly on it ran as free as if had been in the country, but as Leeds expanded, the beck was culverted and largely covered over. However, you can still see a few traces at the bottom of Sheepscar, where the two streams meet and the mill pond would have been, just below Bristol Street.

It’s also easy to track here and there along Mabgate – a bridge crosses it on Hope Street – before one final glimpse as it vanishes underground, not too far from the Eastgate roundabout.

Going underground

Going undergroundThe culverting and covering of Timble Beck was a massive undertaking, as this picture shows.

Where Timble Bridge once stood.

By several names, beck and bridge have featured in any number of my books. It was a totem throughout the Richard Nottingham series, and has played a large role in the Simon Westow books. For the most part, Leeds hasn’t been kind to its own history, treating it as something in the way instead of worth saving.

But the beck, or what few bits you can still see, is history right under your feet. It’s powered mills, it’s flowed through the history of this place. These days it’s greatly diminished, but the role it played in helping Leeds develop, especially Leeds industry, is huge.

Lady Beck/Timble Beck

Lady Beck/Timble BeckSince you’ve read this far, can I put in a quick plug for my upcoming book, A Rage Of Souls, which will be published October 7. It’s the eighth and final Simon Westow, every bit as dark and explosive as you could wish. Please ask your library to buy a copy, and you can pre-order it for yourself right here. Thank you and keep Leedsing. If that’s’ not a word, it should be.