A Fish Knife

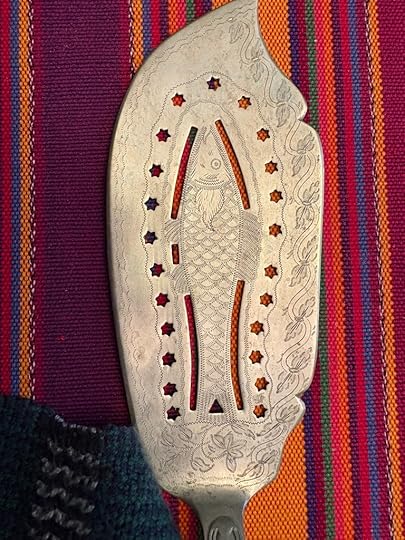

I have a fish knife. Not the kind fishermen use to clean their catch or remove the scales. It’s a serving knife made of sterling silver, about 11” long, with an engraved fish on the blade, surrounded by punched stars and etched greenery. The handle has “EHT” engraved on it. I have no idea whose initials those might be. Worse, I’ve never used it to serve fish, though occasionally it’s been helpful in getting a piece of pie out of the tin.

It’s spent the last several decades rattling around in a drawer with my other mismatched flatware, mostly inherited from dead relatives.

But this oddly ornate serving utensil is part of a national story that began in the Gilded Age, a story that includes several men who had a lot of money and at least one woman who didn’t.

The Influence of the Gilded Age

The Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain, usually refers to the period between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War I. It describes a period of rapid expansion in the US, accompanied by widespread corruption and material excess. John Jacob Astor is a good poster boy for the era, but John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, or J. P. Morgan would also serve.

John Jacob Astor was born in 1763, in Waldorf, Germany, the son of a butcher. He immigrated to the US after the Revolutionary War and, with some help from his older brother, got involved in the fur trade in the northern territories. Since fur was vitally important in cold climates and Europeans had already killed off their fur-bearing animals, Astor saw an opportunity in buying otter and beaver pelts from traders, cleaning them up, and selling them to European markets. It was bloody, smelly work, but it made him a 300% profit over costs – or better. Then he decided to eliminate the middleman and headed west to negotiate directly with the traders and trappers. He often paid less than he promised for the pelts or substituted liquor for trade goods. Sometimes he paid so little to the traders that they wound up killing their trappers, usually Indians, rather than pay them for the pelts they brought in.

When demand for furs began to slow, Astor, with the help of his wife, Sarah Todd Astor, turned to buying up real estate, especially in New York City. The flood of new immigrants meant housing was at a premium, and Astor and his son eventually controlled most of it. He made his biggest returns on overcrowded tenements that were divided and subdivided until a family might be living in an area about the size of an elevator. Even then, the family might rent out bed space to a lodger.

At the same time, Astor joined the opium smuggling trade, shipping opium from what is now Turkey to China and later to England.

He made another fortune by lending money at exorbitant rates and by establishing company stores where employees had to pay high prices or buy on credit because there was no other option.

But Astor wasn’t alone at the top. Powerful monopolies controlled shipping, mining, railroads, meat packing, textiles, oil, coal, steel, tobacco, even fruit. The robber barons, as they became known, ignored criticism and brutally put down any worker efforts to unionize or demand better working conditions. Put this together with new waves of immigrants desperate for work and no income tax until 1913 (the 16th amendment), and you have the formula for the top 1% controlling most of the country’s wealth in the Gilded Age.

Once they had it, they flaunted it. This photo shows a sitting room in John Jacob Astor’s house in New York City.

In addition, they built summer homes north of the city or farther up the coast in Newport, Rhode Island.

Eventually, Astor was considered the richest man in America. But he needed more than money. He needed respectability. A history of success, a lineage, a heritage. He wanted a connection to older European families. Specifically, royalty. His house had to have the same décor as the royal homes in Europe. No longer the son of a butcher or a fur trader with blood on his hands, he saw himself as a king, blessed by God with rare talents that separated him from ordinary men.

The other robber barons agreed. The elaborate dinners given by Queen Victoria (1837 – 1901) helped cement her reputation and power, so the Gilded Age barons followed her example, down to the table settings and silverware. The centuries-old estates of European aristocrats provided the design templates for homes of the Gilded Age leaders. In fact, many of the greatest homes of the era sported paintings, sculptures, carpets, tapestries, and furniture purchased directly from European castles, in some way carrying with them their old-world blood claims to power.

If you want a first-hand look at this kind of life, check out the “cottages” on Bellevue Avenue in Newport. The largest, “The Breakers,”(shown in the photos) is worth the admission price just so you can gawk at the extravagance of the rooms, especially the main hall.

Other super-rich folks built their summer homes along the same street. That way they could compete and socialize with the right sort of people. Interesting side note: Beachwood, the Astor mansion in Newport, was purchased by Larry Ellison, the billionaire founder of Oracle software, in 2010, so it is no longer open to the public. But it still belongs to the 1%.

The Gilded Age was clearly an era of inequality built on greed. And yet – and here’s the odd part – working people became fascinated with the super-rich.

When the glitterati gave a party, ordinary people lined up on the streets to watch the aristocrats arrive. Local papers provided lists of all the guests and described the decorations and clothing in detail. Even the place settings. It sold a lot of papers.

We still find lifestyles of the rich and famous fascinating. Julian Fellows, the creator of Downton Abbey, has a new hit, The Gilded Age, which features several of the enormous mansions in Newport. The Breakers, along with Marble House, Chateau sur Mer, and The Elms serve as backdrops to this well-dressed production. Their opulence helps describe and define the people who play out their personal dramas there.

The Rise of the Fine Hotel

Exclusivity was always part of the Gilded Age appeal. But later, this sense of grandeur became somewhat more widely available in the most fashionable hotels, like the Waldorf, opened in 1893, and the Astoria, opened in 1897, by competing members of the Astor family. There, rich people could enjoy the same sort of luxury the very rich enjoyed, including fine dining. The photo shows a main ground floor room in the Waldorf, clearly modeled after the decor of the Gilded Age estates.

You could also go to an important dinner at the Waldorf and, for that moment at least, become one of the elite. The photo (left) shows a banquet held at the combined Waldorf-Astoria hotel in 1903. Clearly, the dress code was very strict.

If you look at the scene from Titanic in which Jack Dawson, played by Leonardo diCaprio, is invited to join the group for dinner in the first class dining room, you’ll notice the amazing array of silverware in each place setting. “Is all this for me?” Jack asks Molly Brown, who whispers, “Just start at the outside and work your way in.” In truth, knowing which utensil to use was a kind of test. Only those raised with money would know. It was as telling as the clothes you wore. https://www.google.com/search?q=You+Tube+Titanic+dinner+scene+with+Jack+and+Rose&oq=You+Tube+Titanic+dinner+scene+with+Jack+and+Rose&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUY

You can still buy full sets of sterling silver dinerware, if you’d like. They cost about $4000, though a set of English King Gold by Tiffany and Co Sterling Silver Flatware (gold over silver) service for 12 would cost you about $60.000! Sets like this are advertised as suitable for the elite, those who want to set a dining table of “unmatched luxury and heritage. It’s interesting that you get heritage along with luxury. A prestigious family history is apparently included in the purchase.

The Legacy of the Gilded AgeThe Panic of 1893 led to bank and business failures. In many ways, it was the beginning of the end for the Gilded Age, but the ostentatious display of wealth continued well into the Progressive Era. And the not-so-fancy people took notes on it. Even if they did not have millions, they could set a beautiful table, with fine china and silverware, kind of like the really rich folks. So they did. Eventually, fancy plates, silverware, and glasses became an important part of many households, handed down from one generation to the next and brought out for special occasions.

Now, though, people don’t see these things as all that impressive. Few people hold formal dinner parties. Even fewer care how you’re supposed to hold a pickle fork or an oyster spoon. Grandma’s collection of silver and china often sits unused in the basement.

That’s probably why the fish knife wound up in my drawer.

Women’s Wealth

But there’s another way of seeing that silverware.

The Gilded Age was an exclusive rich white man’s club. Women were useful in ensuring the legacy would continue through children and for displaying the husband’s wealth. But they had very little real power.

They couldn’t vote. (Women didn’t get the vote in the US until 1920, and women of color weren’t included until 1965.) They had no financial independence. (Up until 1974, a woman could not open a bank account in the US in her own name without her husband co-signing, or apply for a credit card, or get a home loan without her husband’s permission. An unmarried woman would be refused immediately.)

During the Gilded Age, when a woman married, her wealth became her husband’s property, even if she brought the money into the marriage.

However, there were exceptions. She could keep her jewels and precious metals, especially silver and gold.

Therefore, her collection of silver flatware, silver coffee service, and silver serving dishes became more than a pretty addition to the table or a way to impress guests. It was an emergency fund, her protection against the threat of destitution. As were her jewels. Many women, faced with bills to pay, secretly sold off some of their jewels and substituted fakes, hoping no one would notice.

So the silver fish knife represented two things to whoever “EHT” was: status and wealth. It said she was someone of a certain class because she had an array of silver dining implements and knew how to use them. Perhaps more importantly, It also represented her personal wealth, which was not under her husband’s control.

And it was something she could pawn when she needed cash. For reference, a sterling silver asparagus server, offered in a 2021 Jewelry, Silver, and Rare Coins Auction, sold for $310. It makes me look at the fish knife with new respect.

Sources and interesting reading:

Donnely, Leeann, “Dinner Is Served: Setting the Banquet Hall Table,” including information on A Vanderbilt House Party – The Gilded Age, https://www.biltmore.com

“English King Gold by Tiffany and Co Sterling Silver Flatware Set 12 Service 256 pieces,” originally sold for $250,000, available on Ebay, https://www.ebay.com/itm/156915667985trjoarns=amchiksrc%3DITM…

“John Jacob Astor,” Britannica Money, https://www.britannica.com/money/John-Jacob-Astor-American-businessman-1763-1848

“John Jacob Astor,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Jacob_Astor

Lewis, Jone Johnson, “ A Short History of Women’s Property Rights in the United States,” Thought Co, https://www.thoughtco.com/property-rights-of-women-3529578

Little, Leland, “Queen Victoria at the Table: The Original Influencer,” https://www.lelandlittle.com/story/queen-victoria-at-the-table-the-original-infuencer/106751/

“ A Piece for Every Food,” Antiques Q&A, https://antiquesqa.blogspot.com/22019/04/a-piece-for-every-food.html/

“Waldorf-Astoria (1893 – 1929)” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waldorf-Astoria_%281893-1929%29

Photos taken from sources listed