Do You Know How To Do A Deep Dive?

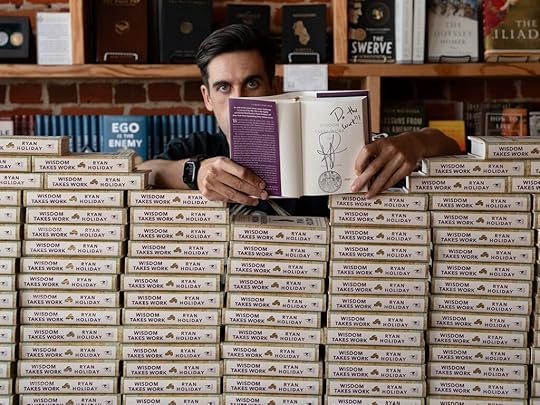

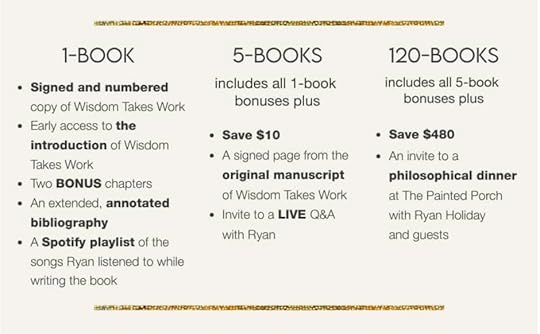

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work , comes out in 13 DAYS! If you’ve gotten anything out of my writing over the years, it would mean the world if you preorder a copy . Preorders are the single best way to support an author and help a book get off the ground. To make it worth your while, I’ve put together a bunch of bonuses—signed and numbered first editions, a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and more. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

I thought I knew a lot about Lincoln.

I’ve read biographies—an embarrassing amount of them honestly. I’ve watched documentaries. I’ve interviewed scholars. I’ve traveled to many of the sights. I’ve read many of his favorite books. I’ve immersed myself in the world he lived in. I once stood transfixed, for hours, in front of Krzysztof Wodiczko’s art piece, which projected the faces and experiences of American veterans on the face of Lincoln’s statue in Union Square Park in New York.

I’ve even written about him quite a bit in my books.

So when I sat down to put together what was intended to be Part III of Wisdom Takes Work, I thought I was set.

It turns out I wasn’t even close.

I was stuck and I could not find the words. That might seem like writer’s block but it wasn’t—because writer’s block doesn’t exist. What is real is lacking material and that’s what I was facing.

So I got to work.

I read Michael Gerhardt’s 496-page book on Lincoln’s mentors.

I read Hay and Nicolay.

I read Doris Kearns Goodwin’s 944-page Team of Rivals.

Still, there was more to know.

So I read David S. Reynolds’s 1088-page Abe, David Herbert Donald’s 720-page Lincoln, and Garry Wills’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book specifically about the Gettysburg Address (Wills’s book has many more pages than the address has words).

I spoke with the documentarian Ken Burns about him, and Doris too.

I went back through the books I’d already read (William Lee Miller, especially, but also Harold Holzer, Joshua Wolf Shenk, and Carl Sandburg).

I read Lincoln’s own writings, his letters and his speeches.

I reviewed my pictures from trips to Gettysburg, Antietam, and Ford’s Theater.

I went, multiple times in the course of writing the book, and looked up at the Lincoln Memorial.

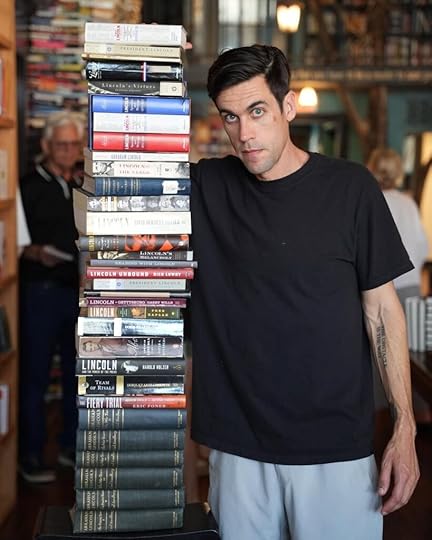

In the end, I spent hundreds of hours reading thousands and thousands of pages on the man. Here’s what that looks like in physical terms.

Basically, what I was doing was a deep dive. Fittingly, Lincoln’s own education was itself a kind of lifelong series of self-directed deep dives. He got his start in law, for instance, when he met a lawyer named John T. Stuart, who allowed Lincoln to borrow some of his law books. “If you wish to be a lawyer,” Lincoln would later tell a young man, “attach no consequence to the place you are in, or the person you are with; but get books, sit down anywhere, and go to reading for yourself. That will make a lawyer of you quicker than any other way.”

His campaign against slavery, too, began by going deep. “He searched through the dusty volumes of congressional proceedings in the State library,” William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, recalled, “and dug deeply into political history.” His way, Herndon observed, was to dig up a question by the roots and dry it out by the fires of the mind, until he could see it for what it was.

Do you know what Lincoln did after the Civil War broke out? He broke out an old habit, which he’d had since his time in Washington as a congressman: He called for books from the Library of Congress, reading everything he could about strategy and tactics, including books published by his own generals. He was, by the end of the war, according to General W. F Smith, “the superior of his generals in his comprehension of the effect of strategic movements and the proper method of following up victories to their legitimate conclusions.”

Nowhere was this ability to see things plainly more evident than in the Gettysburg Address, which was just 271 words long. You might think such a short speech was easy to write, in fact, it was the descendent of a decade-plus-long deep dive into language, elocution, rhetoric, history, law, politics and the founding ideals of the nation—a word he repeated in the speech five times. It was an expression of the work Lincoln did to get to the “nub” of a subject, as his law partner said. As Wills writes in Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, Lincoln was able to, as a result of his masterful understanding of the issues and opportunity at hand, to effectively redefine and refound the nation in a single speech, in a way that two and a half years of war had not been able to.

Going deep in order to get to the nub of subjects—this is a skill you need to have. Whether you are an author, a politician, a lawyer, entrepreneur, scientist, educator, parent—it doesn’t matter you have to be able to pursue an idea, a question, a thread of curiosity until you’ve wrapped your head completely around it.

In Right Thing Right Now, I spend a lot of time talking about the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who like Lincoln was able to strike a defining blow against slavery. Obviously this is what we’re talking about when we talk about justice. But how did he do it? Clarkson knew slavery was wrong. He even wrote a convincing essay on it.. But he soon realized that if he was going to do something about it, he would really have to understand slavery—as a business, a logistical enterprise, and a set of cultural assumptions passed down for thousands of years to justify it. So he immersed himself in the abolitionist movement, meeting and learning from the earliest activists, reformers, and freed slaves. He visited slave ships. He would recall that the almost uninhabitable quarters, the chains and grates, filled him “with melancholy and horror,” kindling, he said, “a fire of indignation.” But now his anger was fueled by facts, and he wanted more. He spoke to everyone he could find who had been to Africa, recording their accounts in his notebooks. He scoured records at the Custom House, poring over muster rolls, ship logs, trial transcripts, and insurance files.

Often falling asleep over paperwork, surrounded by his research, Clarkson persisted for years. By the end, no one knew more about the slave trade—he was more informed than many traders and investors themselves, since so much of what they did depended on deliberate ignorance.

You can’t solve a problem you don’t understand. You can’t lead a field you haven’t immersed yourself in. You must go down the rabbit hole. You must go deep. You must swarm the topic.

This has been my approach to pretty much everything I’ve done since dropping out of college. It’s how I figured out how to be a writer. It’s how I figured out how to be a researcher. It’s how I figured out how to be a parent. It’s how I figured out how to run a bookstore. Indeed, my whole life has been built on deep dives.

If our goal is to get not just smarter or more knowledgeable, but wiser, we cannot be content to learn in half measures. We must go as deep as we possibly can. We don’t just read a book on a topic. We have to read everything we can find on it. We don’t just ask a question or find an expert. We have to find every expert we can and ask them every question they’re willing to answer. We don’t just look at what’s there. We have to explore the remotest corners, every facet, from every angle. We have to hear from people we agree with and from people we disagree with. We have to go out and get real experience.

As an old man Marcus Aurelius would reflect on the most important lesson he had learned from his philosophy teacher Rusticus: “to read attentively—not to be satisfied with ‘just getting the gist’ of things.” Go “directly to the seat of knowledge,” he said. Immerse yourself in the craft, business, sport, or profession. Seek out tutors and mentors and peers. Travel. Observe. Ask questions. Go way beyond the “gist.”

The great biographer David McCullough talked about swarming the subjects he wrote about—reading their diaries, their favorite books, biographies of their heroes, newspapers from their time, and, most importantly, spending time in the places they had spent time. “I believe strongly,” he once said, “that terrain, landscape, the physical environment is not just important in understanding someone or something—it’s elemental. Therefore, I go to where things happened.”

The jazz legend Miles Davis didn’t just go down to the club and listen to music. “I would go to the library and borrow scores by all those great composers, like Stravinsky, Alban Berg, Prokofiev. I wanted to see what was going on in all of music,” he explained. All of music. Old stuff. New stuff. The greats. The weirdos. “Knowledge is freedom and ignorance is slavery,” he said, “and I just couldn’t believe someone could be that close to freedom and not take advantage of it.”

The Wright brothers didn’t discover flight through a single epiphany but through countless hours watching birds. “We couldn’t help but thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts,” one Kitty Hawk resident recalled. “They’d stand on the beach for hours, watching the gulls flying, soaring, dipping.” They even studied how paper fell and floated to the ground, again and again.

Wilbur’s notebooks are filled with drawings of birds, notes on flight techniques across species, and how weather affected flight. They include sketches of wind-tunnel tests and designs. Others had observed birds, but no one had gone so deep—or spent so much time—studying the mechanics of flight and wings.

To capture the progression from ignorance to knowledge to wisdom, McCullough used the example of the pilot’s cockpit. You can get a pretty good understanding from someone describing what a cockpit is. An even better understanding from reading about cockpits. An even better understanding from looking at pictures. An even better understanding from watching videos. An even better understanding from sitting in a cockpit. And an even better understanding from flying a plane.

This is our job. To make things clear. To get to the nub of things. To find what is important and discard the rest. To go deep. To swarm.

This, of course, takes time.

It takes curiosity.

It takes patience and persistence.

Most of all, as I put in the title of the new book, it takes work.

***

For the past six years I’ve been going deep on the four virtues, and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the Stoic Virtues series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

The book comes out October 21st, but it would mean the world to me if you could preorder the book from dailystoic.com/wisdom . Preordering a book is the number one thing you can do to support an author as they get a book off the ground. It’s how publishers determine how many copies to print, whether other bookstores will carry it, and where the book will land on the bestseller list.

To make ordering it early worth your while, I put together a bunch of bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and a bunch of other stuff. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.