Storybelly Digest: 14 Days in October

Afternoon, Storybellers, Debbie here with some context for my documentary novel Countdown.

Tomorrow, October 14, marks the date in 1962 that a U-2 spy plane flying over Cuba captured photographic evidence of a Soviet missile buildup 90 miles off the coast of Florida. The Cold War began heating up.

When you’re a kid, you can’t really understand the scaffolding that underpins adult concerns. Nor should you have to, of course. But that lack of understanding can lead to some pretty serious heart palpitations.

Even if you’ve got adults who talk with you about your fears, there is by nature a lack of context available to young minds and hearts. We haven’t lived long enough yet.

And, often, when a bunch of kids get together, there is a great willingness to pre-disasterize the possibilities. Right?

I was in that boat — along with so many of my classmates and friends — in October 1962, when President Kennedy appeared on television to tell the American public that Russia had installed operational medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles on the shores of Cuba — missiles that could reach most major US cities from Cuba.

“Pointed right at us,” said one of the parents in our neighborhood. “We’d all better get ready for World War III.”

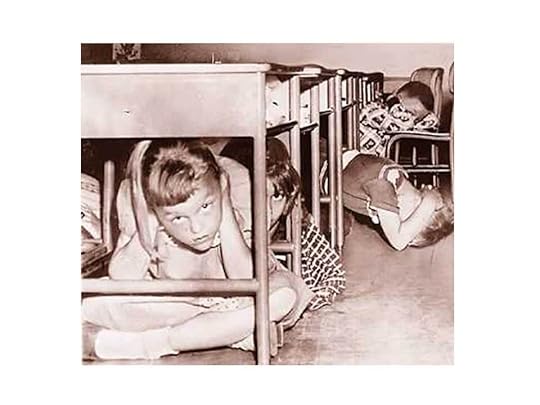

At school we began duck-and-cover drills every day. If we were walking down the hallway when the siren sounded, we were to hug the wall with our bodies rolled up, hands clasped behind our necks, heads tucked into our laps.

We were marched into the cafeteria to watch Civil Defense films. Every day during those two weeks, we were tested to make sure we were ready in case of nuclear attack by the Russians.

President Kennedy addressed the nation on October 22 and said:

It shall be the policy of this Nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.

I could not fathom it. I wrote a letter to President Kennedy:

If you would just invite me to the White House, I could tell you why you don’t want to blow up the world.

Because when you are nine — or ten, or seventy-two — you get it.

It’s simple.

Just stop.

All of this was scary enough, but none of it compared to the fear I felt at home. My father was the Chief of Safety for the 89th Military Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base just outside of Washington, DC, and one of his responsibilities was to ensure safety on the tarmac for Air Force One, the blue-and-white jet that still today flies the president and other dignitaries from Andrews to wherever they need to go.

Dad took dozens of photos of safety violations as part of his job, including this one of Air Force One on the flight line in 1962.

Dad took dozens of photos of safety violations as part of his job, including this one of Air Force One on the flight line in 1962.Dad was on high alert for the two weeks of the Cuban Missile Crisis — we didn’t see much of him — and Mom was busy preparing us for nuclear attack.

She never said so. I found out because I opened the downstairs closet door to get whatever-it-was I was after — I no longer remember what — and instead of what was usually there, I encountered a fallout shelter’s worth of supplies:

Canned and boxed food. Blankets and pillows. Matches and candles and Sterno. Flashlights and batteries. Water in canning jars. Clorox. Rags. A radio. A first-aid kit. Aspirin. A box of Saltines. Campbell’s soup.

I remember the wash of fear that instantly drenched me — a crackling tingle I could almost hear — from head to foot, across my shoulders, down my arms, into my fingers. I was rooted to the spot; I could not look away. I still remember sucking in a gasping breath and inventorying what I saw.

I knew what this closet meant:

My mother was afraid. How could that be?

From there it wasn’t hard to make a leap to:

There might come a day when my mother and father could not protect me, and they knew this. And then what would happen?

It had never occurred to me that that could happen. I was nine-years-old. My parents were omnipotent — like all parents seemed to me then.

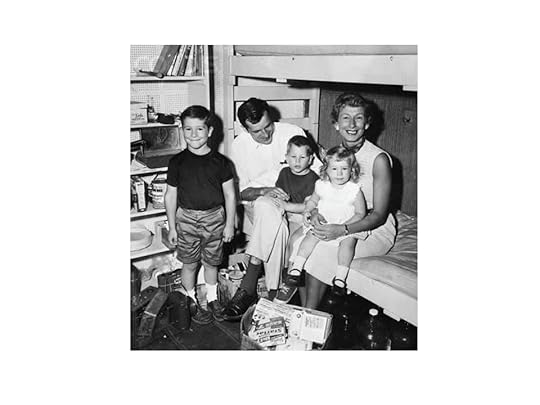

The “happy family in the bomb shelter,” from Life Magazine. (Photos here are from Countdown’s scrapbooks; credits are listed in backmatter.)

The “happy family in the bomb shelter,” from Life Magazine. (Photos here are from Countdown’s scrapbooks; credits are listed in backmatter.)People ordered plans to build bomb shelters in their yards, like Uncle Otts does in Countdown. And I made plans of my own: If the air raid siren went off for real — not the “Alert” tone, but the “Attack” tone — which we had been schooled to listen for — I would NOT duck and cover under my desk. I would run to the other side of the school, to my little brother’s classroom, and I would yank him out of there, and we would run home as fast as we could. We were “walkers,” anyway, we always walked to school, and we didn’t live far away.

My reasoning was, if I was going to die, I was going to do it in the arms of my family. I didn’t know then — and no one told me, or the American people — that had those Russian missiles been fired, we all would have been vaporized.

My heroine in Countdown is Franny Chapman, age eleven. She is a stand-in for me, as is her little brother Drew, who is nine, and her older sister Jo Ellen who is nineteen. Each character in the book represents a facet of that time period, from Franny’s Air Force pilot dad to Uncle Ott’s who tries to build a bomb shelter, to the teachers, neighbors, and friends, along with the customs and norms that peopled my world in 1962.

Writing Countdown helped me understand what I couldn’t grasp when I was nine. What the heck was it all about? I needed to know.

Writing Countdown took me back to a more innocent time as well, if you can call almost being blown up an innocent time.

I think you can. It’s those opposites that Uncle Edisto talks about in Each Little Bird That Sings. We can’t live life without them.

I think of young people today — my grandgirls especially… and all the students I’ve worked with for over 25 years, working in schools, presenting books, asking young people to tell their stories, workshopping with them across the country, watching them build their scaffolding, face their fears, find their anchors, and write their stories.

In my experience, what they lack is what I lacked in 1962: Context. That will come.

What they have now is what I had in 1962, and maybe this is the most important thing: A heart that wanted safety, and happiness, and love. For everyone.

I know we can’t always choose what happens in the world. What we can do is learn to choose our response.

Which is why I wrote this conversation in Countdown between Franny and her older sister Jo Ellen, who is preparing to go south for Freedom Summer soon. I want young readers to think about how they do have choices to make, as their context grows, and as their hearts expand.

Franny begins:

“I’m going to change the world, too,” I say.

“What’s your plan?”

“I’m writing a letter to Chairman Khrushchev.”

“You are?”

“I am. I’m composing it at night, in bed.”

“What does it say?”

“It says I want to meet him. If I could just talk with him, I know I could convince him to stop scaring the pants off everybody.”

I can’t help it — I cringe, waiting for Jo Ellen to laugh at me. Instead she says, “That’s a good idea. How would you convince him of that?”

I sit up straight to make my point.

“I would tell him we’re all just people, here in America, and we don’t want to hurt anybody. We just want to live and be happy.”

“My thoughts exactly,” says Jo Ellen. “But don’t you think he knows that, Franny?”

“Well, evidently not! If he knew it, he wouldn’t behave like this.”

“He knows it, Franny. It’s complicated. I don’t think anyone wants to bomb anyone else.”

“How can you be so sure?”

Jo Ellen drops her compact into her purse, looks at me, and says, “There is more going on in the world than the Russians and the Americans screaming at each other about atomic bombs, Franny. Things that are just as scary, actually.”

She sits next to me on the bed, takes my hand in hers, and says, “There are always scary things happening in the world. There are always wonderful things happening. And it’s up to you to decide how you’re going to approach the world… how you’re going to live in it, and what you’re going to do.”

I don’t know what the heck she’s talking about.

“Are we going to get bombed by the Russians, Jo Ellen?”

“No.”

“I’m not so sure. I’m still writing my letter.”

“Good. That’s one way to change the world.”

Who we listen to — and how we listen, and how facts and wisdom are dispensed — matters.

I take my life and I turn it into stories. I say I write for ten-year-old me, as I have a vivid memory of my childhood years and I have stories to share, but really, my stories are for all ages.

Young people, though…. young people are just beginning to try and make sense of their world. I hope a book like Countdown helps.

I know it helps me to “write my letter.”

xoxo Debbie