CMP#230 Agatha, the Scooby-Doo heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#230 A very posthumous novel, or Agatha, the Scooby-Doo heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#230 A very posthumous novel, or Agatha, the Scooby-Doo heroine

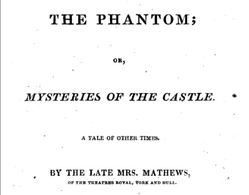

This post is yet another entry in the series clearing up the

tangled attribution

chain of aspiring authoress

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

(EKM) who died in 1802. 23 years after her death, London publisher Oddy & Co. issued an inexpensive one-volume novel titled The Phantom, or, Mysteries of the Castle, “by the late Mrs. Mathews, of the Theatres Royal, York and Hull." The story was offered for a mere four shillings--you can compare some other prices on their "new publications" list at right.

This post is yet another entry in the series clearing up the

tangled attribution

chain of aspiring authoress

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

(EKM) who died in 1802. 23 years after her death, London publisher Oddy & Co. issued an inexpensive one-volume novel titled The Phantom, or, Mysteries of the Castle, “by the late Mrs. Mathews, of the Theatres Royal, York and Hull." The story was offered for a mere four shillings--you can compare some other prices on their "new publications" list at right.James Burmester, an antiquarian book expert, pointed out that this London edition appears to be a re-issue of an earlier book that never made it onto any publication lists. Although the London publishers are on the title page, a publisher based in Hull has his imprint on the back of the title page and at the end. And Hull is where EKM lived with her aspiring actor husband Charles Mathews before they moved to York.

But what about this business of being of the Theatres Royal [in] York and Hull? It's Charles Mathews' second wife who was the actress, not EKM. But Anne Jackson Mathews --herself a published authoress--was alive when The Phantom came out; she was not "the late" Mrs. Mathews.

In Charles Mathews' memoir, there is no mention of EKM ever treading the boards--can she be described as being "of the Theatres Royal, York and Hull"? My research has turned up the fact that EKM did take to the stage, once in York and once in Hull, on her husband's "benefit nights." (Those are special performances when the profits from the night go to the featured performer.) So, while it might be an exaggeration, EKM could technically be described as being of the Theatres Royal of York and Hull.

This declaration jazzed up the title page of The Phantom and made the connection to the by-then-famous Charles Mathews clear to the reading public. More about EKM's theatrical career another time. Now, on to the novel itself... In previous posts, I discussed the characteristics of EKM's writing--characteristics that she shared with dozens if not hundreds of other writers, such as rapturous appreciation for scenery, moral didacticism, a heavy reliance on metaphorical phrases like "tear of sympathy" and "balm of consolation," narrative interjections and forewarnings, and so on. So instead, let's meet our (standard) characters of this gothic thriller.

We begin with our bad guy

We begin with our bad guyOur tale is set in medieval times. Mortimer Mordaunt, the Earl of some random castle somewhere in England. “The earl’s person was handsome and majestic, yet the deep furrows of care were imprinted on his brow. An air of conscious superiority marked his every action, while beneath the specious mask of politeness, he endeavoured to conceal an haughty, vindictive, and imperious spirit.”

“In pursuit of a favorite scheme his mind was strong and inventive. Religion he contemned as the work of priestcraft, and the resource of weak and enthusiastic minds.” (Here we see how people used the word “enthusiastic” in those days to signify over-the-top and irrational religious devotion.)

The earl is the guardian of the beautiful Agatha, whose parentage is a mystery. She has been raised in a nearby convent.

The earl knows he should leave Agatha in the convent and encourage her to take her vows, but “her loveliness continually disarmed him of those suggestions of prudence.”

The lovely Agatha

The lovely AgathaOur heroine checks all the boxes. She has “dark and expressive eyes" and a "luxuriance of bright amber hair” and "“a bosom unsullied as the mountain snow.” She is “unaccustomed to the gaudy scenes of life, and... Agatha breathed not a wish beyond the sanctuary which had sheltered her infant years, nor sighed for other society than those friends who had cherished the seeds of virtue in her mind, and stored it with useful and elegant instruction.”

Agatha is brought from the convent to the castle--and of course she is enraptured by the scenery along the way: “the castle, the surrounding country, the hoarse murmurs of the river, and the melodious songs of the warblers, all had power to cheer and enliven the heart of the innocent traveller. Her mind, pure and unsullied from baneful passions, received with enthusiastic rapture, the sentiments which scenes like these engender in the heart consecrated to virtue. Happy, thrice happy state of purity!”

But she is very uneasy to take up residence with the Earl Mowbray, who clearly, ahem, admires her. Agatha tells the neighbourhood religious hermit of her troubles, “she saw the tear of commiseration gather in his eye, then burst from its bounds, and stray to his venerable beard. Affected by his tender sympathy, she pressed the extended hand of her worthy preceptor to her ruby lips, and with winning softness wiped away the tear of feeling.” The castle is haunted by a phantom who shows up to give Agatha some timely advice. “’Fear not, my child,’ said the phantom, ‘I come to warn you of impending dangers, to strengthen, not to terrify. Mowbray speeds his way to the castle, beware of his evil machinations, avoid the murderer, the murderer of thy mother!’ ‘Gracious God!’ exclaimed Agatha, ‘my mother’s venerated name; tell me, celestial being, in pity tell me, who was my mother?’ ‘Time,’ replied the phantom, ‘and holy angels will withdraw the veil of mystery, adieu!’”

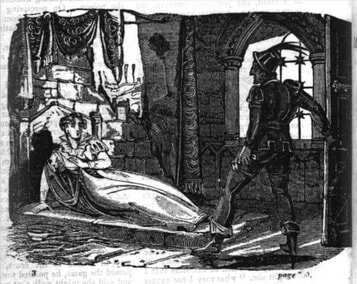

Original frontispiece The threat

Original frontispiece The threatThe danger, it becomes clear, is the lascivious propositions of Agatha's evil guardian. “[A] glow of virtuous indignation dyed her cheeks as she exclaimed, 'leave me, my lord, nor even dare again to insult me with proposals which my soul shrinks from with disdain!'

'Haughty girl,' replied he earl, 'do not provoke my vengeance, remember thou art in my power, tremble therefore, and be submissive.'

'Never! My heart scorns fear and submission, let the guilty tremble, and bow their heads to the dust, I am innocent!'

'You will repeat of this', said the earl, and hastened from the chamber."

The earl refrains from forcing himself on his niece and decides instead he had better have her killed--you'll find this same plot point in Ann Radcliffe's The Romance of the Forest. Just as with Radcliffe, it turns out the evil Earl is a usurper who has deprived his older brother of his birthright.

One of the earl's house guests, the handsome Adolphus De Burney, falls in love with Agatha, so he helps her escape through a secret tunnel to the home of the neighborhood hermit. Then he escorts her to a more distant convent, in the hopes that the Earl can't find her there. But he has to set out for the Crusades, so the lovers (I mean that in a romantic sense) must part.

One of the earl's house guests, the handsome Adolphus De Burney, falls in love with Agatha, so he helps her escape through a secret tunnel to the home of the neighborhood hermit. Then he escorts her to a more distant convent, in the hopes that the Earl can't find her there. But he has to set out for the Crusades, so the lovers (I mean that in a romantic sense) must part. The evil Earl recaptures Agatha. He locks her up for the time being in his spare castle, overseen by “the loquacious [servant] Debora.” Debora is thrown into a flurry when her master arrives, “ye blessed saints defend us… here’s the earl arrived, and with him such a train of servants; well, well, I must hasten down to receive him, though I never was worse prepared to see his lordship; the castle, as I may say, is all at sixes and sevens… Lord bless us, was ever the like before?”

In contrast, the female servant in Romance of the Forest isn't loquacious (in fact she has no dialogue at all). She isn't used as a confidante for the heroine or a device for exposition, either.

At any rate, Agatha manages to escape. Two mysterious female pilgrims show up and tell Agatha to come with them. Agatha is escorted back to St. Mary's convent.

Title page of "The Phantom" (detail)

Scooby Doo revelation

Title page of "The Phantom" (detail)

Scooby Doo revelation

We learn that sadly, the hero Adolphus has perished in a shipwreck so Agatha decides to stay at the convent and become a nun. Here is when EKM lets us know that the supernatural Phantom is not a phantom after al! It's Matilda, Agatha's mother (also one of the two mysterious female pilgrims). It might comfort Agatha in her heartbreak to know that her mother is alive, but nah... “Matilda had formed a wish of discovering herself to her daughter, but for the present determined to banish the pleasing idea, fearing it would draw her mind from her religious duties.” Makes sense. And at any rate, there is only one proper time for making astounding revelations, and that is of course, the moment when Agatha is about to take the veil.

Our hero De Burney arrives in the nick of time! He's not dead after all! Our heroine faints, and wakes up to see her father, also returned from the dead, hanging over her.

"At that instant a female rushed into the room, and flinging back her veil, discovered to the enraptured eyes of [dad] Mowbray--Matilda! His adored and long lamented wife! A scene ensued so unexpectedly tender that no being, save a celestial habitant of heaven, can pourtray it. The mind, possessed of sensibility, may imagine what words are inadequate to express."

It turns out that Agatha's father also turned hermit, i.e., he is a man who, on being told his wife and child had died while he was away at war, abandoned his title and responsibilities, and left his dependents and tenants to the mercies of his evil younger brother. He was therefore unaware that his wife, fearing for her virtue and life, had run away from the castle and was living in a cave with her faithful female attendant. As we've seen she occasionally haunted the castle to reproach the evil usurper and to falsely tell Agatha that he was "the murderer of thy mother". But she didn't rescue her daughter by taking her back through the secret tunnel to the same cave. Just... hanging out in a cave for years on end while dad was hanging out in his hermitage near that other castle. But let's not bicker and argue about whose actions made whose life miserable.

When the family is unexpectedly reunited and the false earl exposed as an usurper, Daddy Earl instantly forgives his wicked younger brother to demonstrate his Christian principles, and phantom/wife/mother calls on the heroine (whose real name is Victoria) to do the same: "'[C]onfirm that pardon which your noble sire has awarded to his brother.' 'May heaven bless me,' exclaimed Victoria, in a solemn tone of voice, as she bent over the unhappy Mortimer “as I forgive him.”

It is understood that evil uncle Mortimer will end his days in a monastery. Victoria and Adolphus are married and mom and dad renew their vows. Curtain.

Note the mark of the original Hull publisher and the obsolete use of the long "s". Plots and sub-plots

Note the mark of the original Hull publisher and the obsolete use of the long "s". Plots and sub-plotsThe main narrative I've described is abruptly interrupted three times for the dramatic backstories of three unlucky couples whose romances were thwarted. Inset narratives were exceedingly common in novels of this era--Austen used inset narratives, but more skillfully, as for example, when Colonel Brandon tells his story in Sense & Sensibility. Brandon's story is integrated into the plot. EKM's three sub-plots arguably serve as a tragic contrast to the main plot, and although I haven't read a lot of gothic novels, I suppose it was a common trope of the genre to include several tragic sub-plots involving separated lovers, as for example in Glenmore Abbey (1805) . These sub-plots also padded out the story, and The Phantom, already a short novel, would be much shorter without them. At a time when novelists could spin out a dilemma for chapter after chapter, EKM was quite terse. Here is her entire description of Adolphus' campaign in the Holy Land, something that would have taken--what, more than two years?: "Soon as the crusaders were landed on the shores of Palestine, they had repeated skirmishes, in which Prince Edward bore the palm of victory. In one of these skirmishes, Adolphus de Burney received a wound in his side, which had nearly proved fatal, and he was borne off the field of battle on the bucklers of his soldiers....[he convalesces and] the idea of again beholding his beloved Agatha enlivened his heart; joy sparkled in his eyes, and the roseate glow of hope animated his cheeks. The voyage was short and pleasant; they were now within sight of Albion’s white cliffs, and the sailors hailed with rapturous shouts their native shore.”

The Phantom reads as the production of a teenager who is a big fan of Gothic novels. There's nothing wrong with that--its how many writers learn their craft, by imitating others. I really need to read Percy Bysshe Shelley's two gothic novels that he published when he was a teenager sometime. There is no mention of The Phantom in Anne Jackson Mathews' memoir of her husband but she does say "no publisher thought [EKM's writings] worth much more than the cost of printing." I'm guessing EKM paid to have the novel printed (just as Austen did with Sense & Sensibility) but the gamble did not pay off in Hull and she was left with a lot unsold novels. A foreword that is also a disclaimer

By the 1820s, the craze for gothic novels had passed, although the genre still had its fans, of course. I don't know who arranged for the 1825 re-issue of The Phantom. Presumably it was either Charles Mathews, in fond memory of his first wife, or it was Anne Jackson Mathews, who saw a way of disposing of a pile of remaindered books. Who wrote this deprecatory foreword? Was it Anne Jackson, or the publisher?: “The following pages will not attract admiration for the brilliancy of the thoughts, the elegance of the diction, or the strict originality of the character—but the sensible and feeling heart will be interested in the fate of Agatha, who, amidst misfortunes of the most trying nature, preserves the dignity of a virtuous mind, and struggles to bear with calmness and resignation, the unmerited persecutions of [the villain who commits] deeds at which humanity shudders, and pity shrinks from, aghast and trembling.”

For more about the Gothic novels of this era, Ann B. Tracy's The Gothic Novel 1790-1830: Plot Summaries and Index to Motifs is a valuable guide, with an index like no other, with entries for "passage, subterranean," and "relative, lost, discovery of" and "veil-taking, disrupted."

For more about the way writers of this era used words like "serious" and "enthusiast" to refer to religion, I recommend Brenda Cox's book, Fashionable Goodness, Christianity in Jane Austen's England.

Previous post: West Indians in children's books

Previous post: West Indians in children's books

Published on October 14, 2025 00:00

No comments have been added yet.