Day of the Dead - Honoring the Grandmothers

I come from along line of strong, independent, defiant, flawed women. I see myself in all ofthem, all the way back to my great-grandmother.

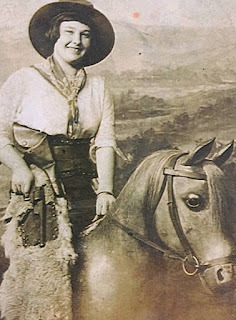

Bertha Gifford, my great-grandmother

Bertha Gifford, my great-grandmotherBerthaGifford, born Bertha Alice Williams, was my mother’s grandmother. She married aman much older than she, and he was unfaithful. When he died, she married a manmuch younger than she. She could, because she was beautiful, but also becausethere had to be something—I mean, I never met her—but for a man of 20 to love awoman of 30, and pursue her, and marry her—there had to be something more thanjust carnal lust. Unless she was the one pursuing him, in which case, knowingthese women as I do, he never had a chance.

But Berthaand Gene were together for decades, faithfully, each committed to the other.Even when Bertha was accused of poisoning people she had cared for as anuntrained “volunteer nurse” in their community, Gene remained loyal to her. Andeven when Bertha went to trial and was subsequently remanded to an institutionfor the criminally insane, Gene stuck by her for years, driving downthe long, slow gravel roads of Missouri to see her as often as he could… untilhe finally took up with another woman. (Lucky for him she was incarcerated….)

Someone intheir community told a snoopy reporter that Bertha once chased a man off oftheir property with a butcher knife. This story was offered as evidence thatBertha was insane and capable of murder. Was she, though? Because I havequestions about that. Where was Gene when this happened? And for what purposehad the man come on their property? Because this is what I know about somemen—starting with my stepfather and including men I’ve worked with and men withwhom I once attended church—some men believe that they can take what they wantfrom a woman, that it’s their role to dominate, her role to submit. Berthastrikes me as a woman who didn’t cotton to that, a woman who stuck up forherself, and yes, a woman who would grab a butcher knife from the kitchen whenthreatened and stand up to a man and say, “Touch me again and there’s going tobe blood shed and it isn’t going to be mine.” Because I have said these wordsto a man, although I did not have any sort of weapon in my hand when I said it.Is this proof of my own insanity? Am I capable of murder? I will answer aresounding yes to that, given certain circumstances.

My grandmother, Lila Clara Graham (West/Parrack)

My grandmother, Lila Clara Graham (West/Parrack)Bertha’s onlydaughter was my grandmother, born Lila Clara Graham. Lila, a child fromBertha’s first marriage, married a Missouri man, but they soon moved to Detroitso her husband could get in on the growth of this new technology, theautomobile. The marriage didn’t last, but Lila provided for herself by runninga boarding house. Okay, full disclosure, this is what I was told when I wasyoung. In my thirties, after Lila had passed, and I began to ask some criticalquestions of my mother while researching Bertha’s life and alleged crimes, mymother explained that, well, yes, the establishment was actually a “blind pig,”the boarding house being a cover for the illegal sale of alcohol duringprohibition.

“A lot ofdifferent people would come and go,” my mother said, “and it wasn’t the bestclientele, if you know what I mean. That’s why my mother sent me down toMissouri to live with my grandmother. She didn’t want me to be exposed to thekinds of people who hung around there.”

It wasn’tuntil many years after my mother’s passing that I learned from her stepsisterthat the “boarding house” was neither hotel nor blind pig. In truth, Lila ran abrothel. Thus the shady clientele. Thus the need to shield her daughter fromwhat was actually going on with all those folks quite literally “coming andgoing.”

Mygrandmother saved enough money in the 1940’s to move to the West Coast. Gotherself a cute little apartment in Los Angeles and took a job as a cook in abar. She did this on her own, no man in sight. And this was the grandmother Iknew, the one whose daily uniform, whether at home or at work or visiting ourfamily in Lakewood, was a comfortable cotton dress with short sleeves and afull skirt to accommodate her large, round body, covered always with a clean,ironed apron. She made her own clothes, and she made clothes for me and mysister. She came to visit often, sitting at the kitchen table with coffee or acocktail, snapping green beans or shucking corn, gossiping with Mom about theneighbors or talking shit about the men in their lives. Until Mom told her to “stop spoiling” us, shealways brought gifts for us kids—coloring books for the girls, those littlebalsa wood airplanes with plastic propellers that wound up with a rubber bandfor the boys, cinnamon raisin bread, and hugs. Big, soft, laughing Grandmahugs.

Lila laugheda lot, clacking her dentures closed so they wouldn’t fall out of her mouth. Shetaught me my first Spanish words and phrases— con leche, mañana, café—whenI was Kindergarten age. Because when she came to L.A. and worked in the bar,she had Spanish-speaking customers. So she learned to speak as much of thelanguage as she needed to in order to serve her customers. Imagine that.

Lila, mygrandmother, never spoke of Bertha, her mother, never gave a hint that shelived with this secret… that she lived with so many secrets. When her marriageended and she was alone in a big city, she found a way to survive. And when shecould, she pulled up stakes and struck out for the Pacific Ocean, reinventingherself again. She didn’t have a single relative living in California when shecame here. I wish now I could ask her why she came, what her dream was. I wishI could ask about her mother. Mostly I just wish I could hug her again andthank her for my lifelong love of cinnamon raisin toast.

My mom, in uniform

My mom, in uniformMy mother,Arta Ernestine West, was born to Lila and her husband in Detroit. But shethought of Missouri as her second home, loved life on the farm with Bertha andGene, loved fishing in the Meramec River, loved her horse, Babe, loved schooland winning spelling bees. (I never once beat her at Scrabble, but Lord knows I tried.) She loved James, her uncle, Bertha and Gene’s son, who was fouryears her senior. They were hanging out together the day the sheriff drove upand took Bertha away to jail, the day my mother’s life changed forever andbecame one of shame and secrets. Mom had just turned ten.

At twelve,back in Detroit, she was sent to live with her father and stepmother while sherecovered from an illness.

“Ernestinewas very, very sick,” her stepsister told me. “I hope it’s okay to tell youthis; she had syphilis.” (Years before, a doctor had confided to me privatelythat he was treating her for tertiary syphilis. In a terribly awkwardconversation, I tried to explain to my mother, in her late eighties by then,why he was prescribing certain antibiotics. The conversation did not go well.)

Apparentlyone of the customers from the so-called boarding house had… Well, there’s noneed to elaborate… just… more shame and secrets.

My mom leftschool and married the first time at age 15 and was divorced a year or so later.In her early twenties, she roamed around the country, picking up gigs as a nightclubsinger. In 1943, at the age of 25, she enlisted in the branch of service known thenas the Women’s Auxiliary Air Corps, where she learned to drive and service thelarge military vehicles used in WWII.

Until myadulthood, I had no idea Mom had been married three times before she married mydad. I also didn’t know how bad their marriage had been until a family friend,a man who’d been the kid down the street from us in the 1950’s, told me thestory of how Mom and Dad had been at the neighbors’ house for a cocktail partyone night and had exchanged heated words. Mom sassed him, and my father slappedher, at which point my mother grabbed an empty beer bottle and said somethingto the effect of “Come on, Pete, come at me again.”

Shades ofBertha, no?

My fatherdied in 1963, and my mother, with the GED she earned while in the service,found a job working as a clerk for a school district. Somehow she managed tofeed four kids and keep us in clothes until we were old enough to care forourselves.

As I said, Icome from a long line of strong, independent, defiant, flawed women. And I amgrateful every day for that strength of character, that defiant independence,that willingness to do what needs to be done in order to survive. When Idivorced, and my husband abandoned his children, refusing to pay child support,I went to college, earning my degree in four years while raising four kids onmy own and living at the poverty level. People sometimes ask how I did it. Thisis what I learned from these women: We do what we have to do to survive.

What Ilearned further from these women is that no good comes from carrying the weightof shame and secrecy. Unlike them—and because of them—I try to live my life insuch a way that my children and my grandchildren can ask me anything, and I cantell them the truth.

No more secrets.No more shame.

And because Ibelieve in life after death, I know that these three women are with me alwaysin spirit and in power. Lordy, I just wish I could hear what those old gals aregossiping about now.