Ruling in the Name of a Dead King

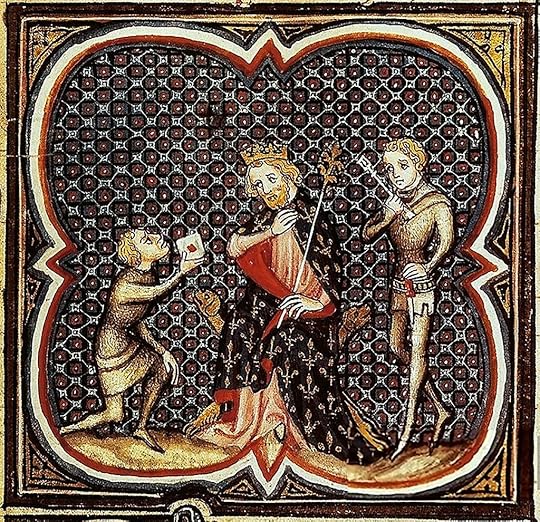

Charles Martel, as depicted in the Grandes Chroniques de France, compiled from the 13th to 15th centuries (public domain image)

Charles Martel, as depicted in the Grandes Chroniques de France, compiled from the 13th to 15th centuries (public domain image)While researching my forthcoming novel Duchess of the New Dawn, I came across something that sounds too weird to be true. When Frankish King Theuderic IV died in 737, his mayor of the palace, Charles Martel (aka the Hammer), my heroine Chiltrude’s father, made a choice unlike those of his predecessors. Instead of setting up a new king, Charles ruled in the name of the dead one — for several years.

At that time, Charles held the real power. He raised the armies and waged war. But the moral authority came from the king, and at that time, only a Merovingian could wear the crown. Apparently, Theuderic had not sired a son, but that would not have stopped Charles. He was no stranger to placing Merovingians on the throne.

Dagobert III, probably a teenager, was king when Charles’s own father, Mayor of the Palace Pippin of Herstal, died in 714, sparking a war for succession between Charles and his stepmother, Plectrude. A year later, Dagobert passed away from an illness. Apparently, he had a son, who would have been an infant or still in utero.

Plectrude’s mayor Ragamfred elevated a monk who assumed the name Chilperic II. About a year later, Charles set up Clothar IV, whom we know almost nothing about, as his king.

Plectrude surrendered to Charles in 717, but the fighting continued. A little more than a year later, Clothar passed, which allowed Charles to make a deal with Chilperic. Had Clothar been murdered? We will likely never know. However, people who were inconvenient to Charles, including his own nephews, had a mysterious way of disappearing or dying.

Chilperic’s reign lasted until his death in 721. Chilperic may have fathered a son (the future Childeric III), but Charles elevated Theuderic, son of Dagobert. The reason is a matter of speculation – sources from early medieval times are often scant on details. Rulers needed support from elite families, and one possibility is that Theuderic, although a boy, would have had more backing.

Theuderic IV, as envisioned by a 19th century artist among the Portraits of Kings of France (photo by ALAIN XD, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Theuderic IV, as envisioned by a 19th century artist among the Portraits of Kings of France (photo by ALAIN XD, CC BY-SA 4.0)Theuderic might have been about 20 when he died. So, why did Charles not choose another king? Perhaps by 737, Charles was powerful enough that the moral authority from a dead king was just as good as a live one.

Another question comes to mind: Why did Charles not seize the throne for himself? In an age when record-keeping was nonexistent and Frankish kings had multiple wives and concubines, it would not be that difficult for him to slip in a Merovingian ancestor.

One possible answer might be hair – or lack of it. Merovingian kings were required to have long hair that never got cut. We don’t know what Charles looked like, but if he had been balding — he was about 51 when Theuderic died — he might have believed his magnates wouldn’t accept him as monarch.

Or maybe Charles was content to have the power without the title. After Charles died in October 741, his sons Karlomann and Pippin found it not so easy to rule without a king. After a few wars with nearby dukes (including Chiltrude’s brother-in-law), they installed Childeric III in 743.

Sometimes, novelists omit a bizarre but true event because readers won’t believe it, which is a valid reason, especially if the occurrence has a minor effect on the story. After all, the key word in historical fiction is fiction. But Charles ruling in the name of a dead king is too big an issue to leave out. That choice plays a large role in the plot and my characters live with the implications of Charles’s choice after he dies.

Preorder Duchess of the New Dawn now on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other vendors.

Sources

The Merovingian Kingdoms 450 – 751 by Ian Wood

The Age of Charles Martel by Paul Fouracre

The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar and Its Continuations, translated by J.M. Wallace-Hadrill

Images via Wikimedia Commons