A grandiose failure?

It’s difficult to assign a definite cause to the short life of Raphael’s, a Chicago restaurant that opened in October 1928 and seemed to have closed by the following July. It would make perfect sense if it had failed after the Wall Street crash at the end of October 1929, but it seems to have closed while the boom was still in progress. [Above: Detail of a platter from Raphael’s shown below, with a fanciful depiction of the building.]

Then again, Prohibition was in effect and that almost undoubtedly contributed to failure. But whatever the cause, Raphael’s on Chicago’s south side didn’t even make it to its first birthday as far as I can tell.

Judging from its exotic design, the restaurant clearly had grand aspirations. Its financial backing totaling $300,000 amounted to a small fortune at that time, equal to nearly $5,700,000 today. At least two thirds of the capital came from a major Chicago investment banker. The remaining $100,000 presumably was furnished by the restaurant’s nominal owner, Edwin Raphael.

In June of 1928, as construction began, the Chicago Tribune ran a snarky story that managed to insult the design as well as Chicagoans’ taste in general. It said that the building “should make one think he’s in Persia, provided he doesn’t know too much about Persian Architecture,” and that it was aimed at “Chicago’s epicureans – if we have any.” [Above: Raphael’s main dining room in 1929]

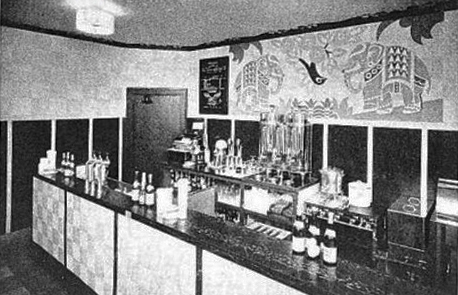

The layout of the building accommodated a small tea garden inside the front door that was outfitted with trees and fountains. Next came a two-story dining room accommodating hundreds, with a ceiling imitating a blue sky with twinkling stars and surrounded on all sides by a balcony that also held tables for guests. Two ends of the building provided people entering from the street access to two interior lunch counters with soda fountains. [Above: one of the lunch counters, but looking strangely like a bar.]

With its minaret, the building reached 60 feet in height and was visible for miles along all three major streets that crossed there. The minaret was used for advertising with neon lighting and a crescent on top. The illustrations used for this building, whether on the restaurant’s dinnerware [shown above] or in advertising, took great liberty in portraying it. [Below: April 1929 advertisement that imagines the building with two domes, four minarets, and palm trees!]

The main dining room featured a band named Raphael’s Persians. Their performances could be heard on the radio at night.

The March 1929 issue of The American Restaurant Magazine hailed Raphael’s for its ability to merchandise meals by “stealing the thunder” of night clubs and offering them stiff competition while putting food “foremost.” When the radio audience listened to the Raphael’s orchestra, the story said, they would feel that the restaurant had “an air of mystery about it” and want to visit “Chicago’s most exclusive restaurant.” But did they?

The combination of three types of eating places in one business was an odd one, something that would be more understandable in a hotel than a restaurant. It would seem as though the tea room and the snack bars would keep earlier and shorter hours than the restaurant/nightclub which stayed open until 3 a.m. and that this would cause staffing problems. By June of 1929 Raphael’s had figured out more ways of making money, as is shown on the advertisement below, such as afternoon dancing, an additional cover charge, and higher cover charges on weekends, but it’s likely that it wasn’t enough.

The trade journal also hailed Raphael’s for its modern kitchen facilities that were filled with the latest mixing machines, ranges, refrigerators, warmers, etc., proving “that the kitchen methods of this modern restaurant are a far cry from the methods employed when the members of Persian tribes would prepare feasts for their shahs.”

A reader of The American Restaurant would be left with the idea that Raphael’s was an elegant place catering to a clientele with sophisticated tastes. But that idea was dashed in a story written by a young reporter who spent a night there playing the part of a “shy cigaret girl.” Over the course of the evening male patrons hit on her nine times. She also observed people drinking alcoholic drinks, probably enhanced by their own whisky flasks. The crowd included teenagers. By June of 1929, the restaurant was reduced to featuring a “crystal gazer” on the balcony named Allah Mahalla. So much for elegance!

Despite serious searching I could find no advertising, nor any mention of the Raphael restaurant at all after July, 1929. In 1940 the address was mentioned as the location of a bunco party (a dice game) hosted by a political group. In 1947 the building, then occupied by a beauty supply warehouse, was auctioned for taxes. It sold for a mere $14,027 plus payment of back taxes of $11,259. The second floor was offered for rent in 1948, and it may have been then that the American Legion moved in. [Above: Could the Hippodrome have occupied the building when this advertisement ran in 1938?]

However, according to a recent Chicago Sun Times story by architectural critic Lee Bey, Raphael’s continued in business until WWII, and “later converted into the American Legion South Shore Post 388.” I haven’t been able to find out why he thought Raphael’s stayed in business that long.

Another eating place that might have once occupied the building (in addition to the Hippodrome) was the Kickapooo Inn. Its address was given as 7901 Stony Island in a 1957 obituary notice for its owner.

The building was acquired by The Haven of Rest Missionary Baptist Church in 1966 and used for church services until 1977 when they built a new church. Now the church is seeking a grant to restore the building, hoping it can be reopened in a few years as a community center. [Above: the building as it appeared recently.]

If any reader has information about this building and its uses over time, I’d love to hear from you. It could assist the church in applying for grants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025