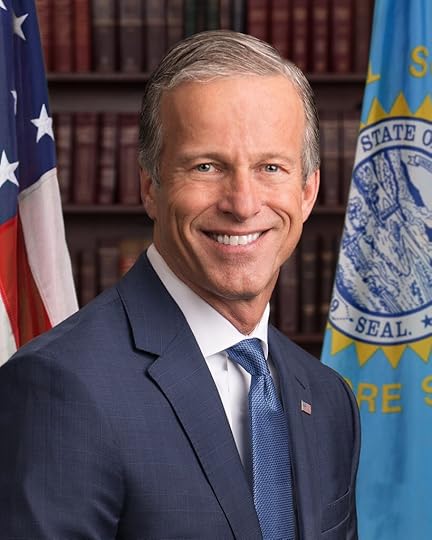

Senate Majority Leader Thune

The Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, is a chronic liar and uninspiring character, at least to this home viewer. From The New York Times:

Mr. Johnson, who without the president’s backing wields little influence over his own members, has chosen to make himself subservient to Mr. Trump, a break with many speakers of the past who sought in their own ways to act more as a governing partner with the president than as his underling.

“I’m the speaker and the president,” Mr. Trump has joked, according to two people who heard the remark and relayed it on the condition of anonymity because of concern about sharing private conversations with him.

(who knows though, maybe that is a “seven almonds” story)

But what about the Senate Majority Leader, John Thune? Everyone seems to like this guy. From a Politico profile by Michael Kruse:

There is, however, a not inconsiderable camp of Democrats and anti-Trump Republicans who expected more. “To the extent that there needs to be Republicans in the Senate, and obviously there’s going to be, I wish they were all like John Thune,” Drey Samuelson, the longtime chief of staff of the late Tim Johnson, the last Senate Democrat from South Dakota, told me. “I mean, I don’t know anybody that really doesn’t like John Thune,” Samuelson said. “I like him.”

from a New Yorker profile by David D. Kirkpatrick:

a city aptly described as Hollywood graduated from for ugly people, Thune could pass for an actual movie star, with pale-blue eyes, a square jaw, and Mt. Rushmore cheekbones. Now sixty-four, he has salt-and-pepper hair that is still thick enough to part neatly on the side, and the broad lats, shoulders, thick arms, and narrow waist of a basketball player. His morning workouts at the Senate gym are legendary. Until a recent knee injury, Thune held the informal title of the fastest man in Congress. (He has likened that honor “the best surfer in Kansas.“)

(why did he say Kansas instead of his home state, South Dakota?)

Thune used to be opposed to Trump:

Thune’s candor often stood out in the course of Trump’s rise to power. During the 2016 race, Thune condemned Trump’s expressions of bigotry as “inappropriate.” After the leak of the “Access Hollywood” video, on which Trump boasted about grabbing women by the genitals, Thune was one of the first Republican senators to demand that Trump quit the race “immediately,” though the election was only a month away. And, even after Trump’s victory, Thune never masked his opposition to the President’s most cherished plans. In a 2017 television interview, he objected to the mass deportation of illegal immigrants, adding that “a lot of my colleagues” shared his view. He has called across-the-board tariffs “a recipe for increased inflation” that would punish South Dakota farmers and ranchers by setting off trade wars. He has consistently stood with what he calls “our trusted intel community” on the conclusion that Russia indeed meddled to help Trump in the 2016 election; he has called Vladimir Putin “a murderous thug” whose invasion of Ukraine proved “the value of NATO.” Thune also often praises wind energy—a booming industry in his home state—even though Trump considers turbines loathsome eyesores.

Trump’s demand that Congress refuse to certify Joe Biden’s 2020 election win elicited one of Thune’s few memorable turns of phrase: he told journalists that the request would “go down like a shot dog” in the Senate. After January 6th, Thune called Trump’s role in the riot “inexcusable.” Linda Duba, a friend from South Dakota and a retired Democratic state legislator whose children used to run in track meets alongside Thune’s, told me that she once asked him what working with Trump was like. “Not fun,” Thune had said. Another old friend was blunt: “I think he thinks Trump’s an ass.”

Not so much anymore. Here’s a (long) recent history of Congress I guess you can skip:

Thune arrived in Congress at a time that now looks like a high point of its power and effectiveness. In the nineties, lawmakers debated issues, committees drafted bills, and the parties compromised to tackle urgent problems.

Congress sent Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton major legislation on trade, crime, environmental protection, financial regulation, civil rights, and other issues. Negotiations between the parties even closed the deficit, briefly.

Philip Wallach, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute and the author of a timely book, “Why Congress,” told me that, looking back, “it’s really amazing-nothing like that has happened in the last fifteen years.”

One turning point, Wallach told me, was Newt Gingrich’s Republican takeover of the House of Representatives, in 1994. Gingrich relished partisan warfare, demanded loyalty from his rank and file, and turned district elections into contests between the national parties. Political scientists have identified long-standing trends that have contributed to the deepening polarization of Con-gress, including the growing ideological homogeneity of each party and the breakdown of the media into echo chambers.

But Wallach is surely correct that Congress, the branch of government designed to mediate factional conflicts, has succumbed to them—and even made them worse.

To more effectively wage partisan battles, Democratic and Republican leaders in both chambers consolidated their own power. Instead of relying on committees to draft bills, party leaders increasingly negotiated significant measures behind closed doors, then brought often in the form of giant “must-pass” bills against a tight deadline, such as measures to keep funding the govern-ment. In the Senate, the concentration of power has been especially stark. Senators used to take pride in proposing amendments during floor debates, facilitating bipartisan dealmaking even against party leaders’ wishes. Yet those leaders now often block individual senators from such freelancing by allowing consideration of only a limited number of amendments and then filling those slots with innocuous proposals of their own choosing—a tactic called “filling the tree.” The former Democratic Majority Leader Harry Reid pioneered this strategy in the two-thousands, and his successors from both parties have kept it up ever since.

In the Congress of 1991-92, Wallach noted, the Senate adopted more than sixteen hundred amendments. In 2023-24, that number fell to two hundred. And the last Congress passed just two hundred and seventy-four bills- down from about seven hundred a year during the late eighties and fewer than any Congress since before the Civil War. Of those two hundred and seventy-four bills, the ten longest were assembled by the party leaders, and they accounted for four-fifths of all the pages of legislation passed in that Congress.

Lawmakers sometimes grouse about their loss of power. Ten years ago, Mark Begich, then a Democratic senator from Alaska, tried, unsuccessfully, to instigate a revolt against Reid’s tree-filling. Lamar Alexander, another critic of the practice, told me that being elected to the chamber now resembled “joining the Grand Ole Opry and not being allowed to sing”

Several senators told me that, at the end of last year, Thune negotiated an agreement with Democratic leaders that allowed Biden to equal the number of judicial confirmations made during the first Trump Administration. In exchange, the Democrats agreed to drop a handful of liberal appellate nominees whom Republicans found especially objection-able, leaving those seats open. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a New York Democrat who participates in a weekly Bible study with Thune, told me that “he was fundamental to all the bipartisan work we did in the last cycle.” For example, Thune helped initiate talks on an immigration bill, even letting legislators use his office. In the end, the bill became a classic example of partisan paralysis: when Trump indicated that he preferred to leave the border problems unaddressed, so that he could keep campaigning on the issue, the Republicans killed the legislation.

The Thune ancedote that stuck with me is this one, from Kruse in Politico:

But Thune decided against a White House run. His mother neared the end, a decade of dementia having taken its toll. “She would sit down at a meal, and she would say, ‘We suffer greatly here on Planet Earth,’” Tim Thune told me. “She might say that 30 times over the next 15 minutes.”