CMP#234 Rebecca the heroine of sensibility

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP# 234 Rebecca the Heroine of Sensibility: Rebecca (1799) by Mrs. E.M. Foster

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP# 234 Rebecca the Heroine of Sensibility: Rebecca (1799) by Mrs. E.M. Foster

No author on title page Rebecca is one of 22 novels that may—or may not—have been written by the author of the 1809 novel The Woman of Colour, a book which has attracted a lot of academic interest in recent years. I’ve been entertaining myself by reading these novels to see if I can find similarities to The Woman of Colour.

No author on title page Rebecca is one of 22 novels that may—or may not—have been written by the author of the 1809 novel The Woman of Colour, a book which has attracted a lot of academic interest in recent years. I’ve been entertaining myself by reading these novels to see if I can find similarities to The Woman of Colour.Rebecca, published in 1799, is one of the earliest in this chain of novels which stretches from 1795, with the historical novel The Duke of Clarence, to 1817 and The Revealer of Secrets. One similarity worth noting is that the father of Olivia Fairfield in The Woman of Colour, and the father of Rebecca Elton in this novel, both tell their daughters who they should marry in their last will and testament.

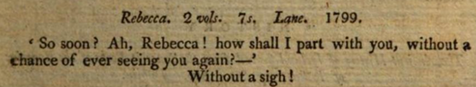

I have a lot to say about Rebecca, even though it is a minor, third-rate novel. It earned only a brief literary snort from the London Review, which quoted a bit of dialogue: “Ah, Rebecca! How shall I part with you?” to which the reviewer answered: “Without a sigh!”

Yes, the dialogue is often clichéd (and exceedingly florid to our modern tastes) and the narration is stilted. In that respect, we can contrast this authoress with Jane Austen. We can compare the themes and tropes of other novels of this era, and at some point, I’ll come back to it to discuss more similarities to The Woman of Colour, but not quite yet... Raging sensibility

The authoress of Rebecca, who has been identified as “Mrs. E.M. Foster,” claims to be an “Old Maid” (The “Mrs.” honorific was given to older ladies at this time even if they were single) who has never experienced “la belle passion” and who derived the details of her love story “from other tender works.” However, her love-scenes are not terse and contained, as with that more famous spinster, Jane Austen. Rebecca is more than a sentimental novel, this is a novel of sensibility. Rebecca's admirers rant, fall on one knee, smite their breasts, and weep. “Oh Rebecca! I cannot suppress my love, my adoration, which at this instant almost madden me… on you alone depends my every moment of future comfort; from the first hour I beheld you, you were the mistress of my fate.”

But so what if Mrs. Foster's writing lacked originality? Modern scholars like Elizabeth A. Neiman speak of the “intertextuality” of the Minerva Press novels. This stable of authors engaged, in a way, in a collaborative effort. The same stock characters, the same sentiments, the same tropes, reappear in many of them. Minerva Press readers knew what they were getting when they borrowed a Minerva novel from the circulating library and this was perhaps the secret to their success in the literary marketplace.

Lansdowne Crescent, Bath A Heroine Enters the World

Lansdowne Crescent, Bath A Heroine Enters the WorldWe meet our beautiful heroine--with her naturally curling hair left unpowdered and dressed in a simple but becoming muslin gown--as she arrives in Bath, where she is instantly dismayed by the contrast between her country home, with its “balmy fragrance of nature in the spring, and... the genial warmth of the sun” and the home of her aunt, with its “sickly glare,” and the “overpowering perfume of rooms, which were prepared for… the most fashionable and brilliant of the company who remained at Bath so late in the season.”

To be fair, something weighs heavily on our Rebecca's mind; her parents want her to marry Reuben Manly, the son of their good friends, the local parson and his wife. They’ve known each other since their infancy and he’s a great guy. But, sighs Rebecca, “I love him with the pure, the disinterested affection of a sister, far different from the tumultuous passion which he professes toward me.”

In Bath, Rebecca's aunt Mrs. Mellville and her cousin Caroline are kind to her. Caroline is saucy and vivacious, except when the subject of Reuben Manly comes up, then she turns red and pale by turns. They all jaunt off to Teignmouth (which is spelled T------- for some reason), and stay at the B----a V----a, that is, the Bella Vista, which is where Jane Austen and her family also stayed in 1802 and 1804. This sea-side resort boasts a circulating library, public rooms, and bathing-machines. And a cast of crazy characters!

Grok-created illustration Personalities and Plots

Grok-created illustration Personalities and PlotsThe Mellvilles socialize with the typical and varied cast of characters who always populate novels of this era. Each one represents a particular moral or social failing which surprises, amuses, or repulses the heroine. There's the oily army captain with his extravagant compliments. The hyperactive Miss Selby goes for long walks and arrives with muddy half-boots and muddy petticoats. The fat and hypochondriacal Mrs. Nesbitt is caught by one visitor: “ravenously devouring a great plate of toast, swimming in oiled butter, the transparent liquid emerging from the corners of her ambrosial mouth.” One is reminded of Austen’s Arthur Parker in Sanditon.

A pair of spinster sisters, the Miss Brownes, do not come in for the usual ridicule meted out to old maids, such as we find with Susan and Diana Parker in Sanditon. They have accompanied their friend Mr. Digby to Teignmouth in the forlorn hope that he will recover his health. Rebecca joins them in attending to Mr. Digby’s bedside as he dies of a broken heart. For one thing, his wife treats him terribly, then she deserts him and runs off with a fortune-hunting soldier. Mr. Digby takes this a lot harder than Mr. Rushworth in Mansfield Park, perhaps he was already consumptive or already heartbroken because his beloved younger sister and his brother-in-law just up and disappeared a few years ago. Nobody knows where they went. If only he could find his sister before he dies!

Rebecca’s got another interesting mystery to ponder—while out on a long morning walk, she comes across a cottage where a young woman and her little daughter live in utter seclusion and secrecy under an assumed name. Who could this woman be?

Colorized by Grok Love amidst the bed pans

Colorized by Grok Love amidst the bed pansAt any rate, Mr. Digby’s brother. Captain Clarence Digby, also comes to Teignmouth to succor him as he’s dying and he falls in love with Rebecca. But “insurmountable obstacles” keep them apart! One obstacle is Rebecca’s vacillation and timidity over whether she should marry Reuben to please Reuben and their respective families. By the terms of her father's will, half of her substantial fortune goes to Reuben if she marries him, but she doesn’t care about that, and she is willing to gift him with half of her fortune anyway, as a sort of consolation prize for not marrying him. But he wouldn't take the money from her, so that’s not really an issue. Altogether, I found these obstacles unconvincing. Just spit it out, girl.

Rebecca is prone to feeling the most exquisite sensations of pity and pain, so she spends a lot of time weeping. I think there must have been a kind of fashion for pale and wan heroines at this time. Like “heroin (not heroine) chic” on the fashion runway. What girl today would be pleased if the man they loved showed up and spoke with concern of her “pallid cheek” and “languid eye”? No woman likes being told that they look tired. Well, Clarence confesses his love to Rebecca, pallid or not, but he thinks Rebecca is engaged to Reuben so, after heaving many a sigh, he takes himself off to the battlefield in despair.

The Reading Rooms at Teignmouth, Thomas Allam, 1830 Staunch conservatism

The Reading Rooms at Teignmouth, Thomas Allam, 1830 Staunch conservatismThis kind of dramatic sensibility is associated with the Romantic era, but the novel also has an emphatically conservative and anti-Jacobin subplot, which warns against the excesses of radicalism. It turns out that Mr. Digby’s missing brother-in-law Mr. Selby was an idealistic young fellow caught up in the dawn of the French Revolution. He goes to France, gets fleeced out of his fortune, then is betrayed and sent to prison. Rebecca’s mysterious cottage-dwelling friend is of course the anguished Mrs. Selby. There is no good reason why this should not have all come to light well before the latter half of the second volume and the only reason it didn’t is the unconvincing behaviour of all involved.

For this and other reasons, Rebecca reads very much like a debut novel, although according to the attribution list, it’s Mrs. Foster’s fourth effort. You would think that by her fourth novel she would know not to name one character “Miss Selby” and another “Mrs. Sedly.”

Some of the group dialogue is lively and natural-sounding, but her narration often reads like a stage direction (“Saying this, the two cousins separated”) and she relies, again and again, on illness and impending death for her plot points. Three couples in this book fall in love when the man admires how well the girl conducts herself while nursing a dying invalid. Illness and death is used to move her characters from point A to point B, or to keep them at point A when they want to go to point B. By contrast, Austen needed to get the Grants out of the way and strike Thomas Bertram with a nearly-fatal illness in Mansfield Park, and she does it with some clever sleight of hand.

Austen's cousin Eliza de Feuillide Anti-feminist message

Austen's cousin Eliza de Feuillide Anti-feminist messageModern academics are in the habit of looking for feminist subtexts and rebukes of the patriarchy in these old novels, and it seems that the best recommendation you can give a forgotten novelist is to call her a feminist. Scholars on the hunt for feminism or other "isms" vastly outnumber scholars who acknowledge the most obvious in-your-face aspect of these novels, which is their Christian moralism. As for the feminism… well, you have to dig for it and ignore countervailing evidence. What about the many critical portraits of women who have plenty of power and who use that power against men? That includes The Woman of Colour, where the villain is a woman.

Unfeminine women are unambiguously condemned in this novel. “Did every female talk and act like [Caroline and Rebecca],” Reuben opines, “the ladies would soon regain that place in the estimation of mankind, which their monstrous and glaring violations of nature have robbed them of.” Poor Mr. Digby is portrayed as being unable to keep his wife under control: “Rebuke, remonstrance had no avail; they returned to England, her conduct still the same, his spirits broken… till unable to bear up against the destruction of all his hopes, and all his happiness, he has yielded to her sway, and, too weak to resist its attacks, is declining to the peaceful grave, the melancholy victim of a mercenary female.” The Amazonian Miss Selby—who admires Mary Wollstonecraft and calls her a “genius”--drowns after taking up gondola-paddling.

On the other hand, a virtuous women can come to grief as well. Through her backstory, we learn that Mrs. Selby unquestioningly follows her husband to revolutionary France and then he instructs her to escape back to England and hide incognito until he can clear his name and return. He never does, and she misses the chance to see her dying brother. Then she learns that her husband has been sent to the guillotine, then her little daughter dies and she goes crazy; all of this seems a disincentive for wifely obedience and feminine submission and an incentive for substituting your own better judgement.

Ouch! Sarcastic review from the Monthly Review. Just as with our previous novel, the heroine does not marry her childhood companion, but marries someone else. Rebecca and Clarence finally sort themselves out, and Reuben consoles himself by falling in love with saucy cousin Caroline, who has always loved him.

Ouch! Sarcastic review from the Monthly Review. Just as with our previous novel, the heroine does not marry her childhood companion, but marries someone else. Rebecca and Clarence finally sort themselves out, and Reuben consoles himself by falling in love with saucy cousin Caroline, who has always loved him. I have just started in on The Duke of Clarence, where the beautiful heroine Elfrida, of noble birth, is growing up in a castle in Wales alongside Edgar, her father's ward, who is the natural son of a knight who died penniless (or is he?). What could possibly go wrong? Mrs. Foster followed up Rebecca with Miriam (1800) and Judith (1800) If the attributions are correct, she also wrote some historical fiction, including The Duke of Clarence.

Top level quiz for Janeites: Did you notice the "sickly glare" that appalls Rebecca when she goes from the city to the country? Remind you of anything?

Here is a brief summary of The Woman of Colour, another modern academic recap which manages to discuss a Christian evangelical novel without once mentioning the religious faith which inspires and consoles the heroine in good times and bad. Is it just considered bad form to mention religion these days?

Jane Austen’s cousin Eliza de Feuillide’s husband the Comte de Feuillide met his end at the guillotine as well. I’m sure relatively few English families could boast this distinction.

Neiman, Elizabeth A. Minerva’s Gothics : The Politics and Poetics of Romantic Exchange, 1780-1820 University of Wales Press, 2019.

Previous post: Substance and Shadow

Published on November 10, 2025 00:00

No comments have been added yet.