CMP#231 Clarissa, the anti-heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#231 Clarissa, the anti-heroine of The Corinna of England

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#231 Clarissa, the anti-heroine of The Corinna of England

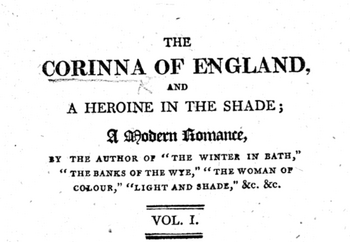

I am slowly working my way through a dozen or so novels, all belonging to a tangled attribution chain, with the intent of figuring out whether Mrs. E.G. Bayfield or Mrs. E.M. Foster is the most likely author of The Woman of Colour, a Regency-era book which has drawn much recent scholarly interest. Next up: The Corinna of England, and a Heroine in the Shade (1809), published by Benjamin Crosby and Co. The fact that the author of Corinna of England is credited as being the author of The Woman of Colour right there on the title page to the right is not enough to prove the attribution, because the waters have been considerably muddied along the way.

I am slowly working my way through a dozen or so novels, all belonging to a tangled attribution chain, with the intent of figuring out whether Mrs. E.G. Bayfield or Mrs. E.M. Foster is the most likely author of The Woman of Colour, a Regency-era book which has drawn much recent scholarly interest. Next up: The Corinna of England, and a Heroine in the Shade (1809), published by Benjamin Crosby and Co. The fact that the author of Corinna of England is credited as being the author of The Woman of Colour right there on the title page to the right is not enough to prove the attribution, because the waters have been considerably muddied along the way.At any rate, let’s turn to the novel. No, wait, we can’t do that yet, until we first explain that Corinna of England is a parody of a tremendously successful French novel, Corinne, or, Italy (1807), by the authoress and public intellectual Madame de Stael.

Corinne caused a sensation at the time but also caused a backlash in England because of its feminist heroine. Corinne is a free-spirited poet and artist who entertained men at her home, did not shy away from fame, and openly courted the man she wanted to marry. The plot of de Stael’s novel is of secondary importance, although I will note two things which struck me; one, that de Stael uses a lot of narrative philosophical interludes which put me in mind of George Elliot, and secondly, after introducing her hero, she has him heroically rescue some people from a burning building. In other words, she gives him some hero bona fides, because otherwise he’s just some rich, well-born Englishman moping around Europe. As I have learned, a lot of leading men in these old novels are not heroes in the sense of being heroic, and some in my opinion are quite unheroic.

So that's Corinne. Now, let's move on to the 1809 parody....

The forlorn orphan meets the flamboyant heiress

The forlorn orphan meets the flamboyant heiress Scholar Miranda Kiek identifies The Corinna of England as an “anti-Jacobin” novel, meaning that it is written from a conservative English viewpoint to counter the philosophies identified with the French Revolution: “a set of beliefs referred to at the time under the catchall term of ‘new’ or ‘modern philosophy’… selfishness masquerading as utility, attacks on family and state religion, sexual voracity, grandiose but meaningless statements… and—for women in particular—a lot of attention and show. New philosophers in such novels can frequently be found advocating for atheism and free love, or knocking down some ancient edifice of England’s mythical Burkean heritage.”

The narrator of Corinne moves quickly to bring her “heroine in the shade,” the demure Mary Cuthbert, together with her flamboyant but wrong-headed cousin Clarissa Moreton (the Corinna of the title). With great narrative economy (telling not showing) she kills off Mary’s parents, a pious and upright clergyman and his wife, and sends 18-year-old Mary to live with Clarissa, who is 22 years old and also an orphan. Clarissa’s father was a successful merchant, and what we would call today a “limosine liberal.” Clarissa imbibed his progressive ideas and now holds court in the family’s old mansion (bought with new money) with a bunch of sycophants and hangers-on, including emigres from the French Revolution.

Mary arrives at this den of iniquity at the same time as one of Clarissa’s English admirers, Captain Charles Walwyn, who has brought along his friend from college, the handsome and upright Frederic Montgomery. Now the actual dialogue and action of the story begins. Both Mary and Frederic are instantly repelled by the freedom with which Corinna comports herself and the fact that she, an unmarried woman with no older chaperon, allows single men and women to live together under her roof. Clarissa’s maternal aunt Deborah also drops by frequently to scold her, but although Deborah’s heart is in the right place, the narrator makes it clear that her manner is so astringent that she does more harm than good.

Clarissa is soon attracted to Frederic, and assumes that he must be attracted to her, since after all, all men are in her thrall just like the fictional Corinne. She has no idea that he is actually drawn to her demure cousin Mary. Parallels with Austen

Clarissa has used some of her wealth to convert the old chapel of the mansion to a (gasp) private theatre! As scholar Miranda Kiek says, the author uses “thudding symbolism” when the local carpenter breaks his thigh when he falls from a scaffold while taking down a crucifix to replace it with a statue of Fame blowing her trumpet. While he is unable to work, his wife and four children face ruin. Mary encounters their humble cottage in one of her early morning walks (like any good heroine, she rises long before the rest of the decadent household) and gives what little aid she can render from her slender purse.

But let’s pause here and remark on the Mansfield Park similarities, which Kiek also saw. A demure and quiet heroine is a “heroine in the shade,” as a good Englishwoman should be. A beautiful, extroverted heiress finds herself unaccountably attracted to an upright and prudish young man who is destined for the church. Private theatricals—the play that Clarissa rehearses alone (on Sunday morning, no less), with Captain Walwyn is The Fair Penitent, a play about adultery. Here is how Kiek describes Mary Cuthbert: “Mary observes and reproves while her flamboyant cousin pronounces and acts. Mary is made the center of moral judgment, if not the center of action.” Sound familiar? But while Austen’s Mary Crawford is actually witty, Clarissa Moreton is a ridiculous egotist, a comic figure. The difficulty for a writer, of course, comes when the foil to your heroine is intrinsically more interesting than your heroine, right?

Courtesy British Museum A spectacle of herself

Courtesy British Museum A spectacle of herself To resume: Frederic Montgomery feels he must depart since he can’t endorse the wild behaviour of his hostess, although he despairs at the idea of leaving innocent young Mary behind in this den of new philosophy. There is nothing he can do about it, though, since Mary is the de facto ward of her older cousin: “yet shall I ever fervently pray for your felicity, and bear about me the remembrance of your wondrous sweetness; even though I should never meet you more—God bless you, farewell, Miss Cuthbert!”

Captain Walwyn is called back to his regiment, but the other inhabitants of the mansion—a French opera singer, two supposed French noblemen, a mediocre painter and an amateur entomologist, continue to enjoy Clarissa’s generous hospitality.

Things get even wilder when Clarissa and Mary drive in the family phaeton into Coventry where they encounter a large crowd assembled for the annual Lady Godiva ride. We never get a description of Lady Godiva, which would have been interesting, but the crowd inspires Clarissa to emulate the Corinne of the novel and make herself the center of attention, so she stands up in her carriage and makes a fiery pro-labor speech which promptly inspires a workers' uprising.

Soon, however, the crowd turns on a dime and attacks Clarissa’s mansion because she harbors Frenchmen and her loyalties are suspect. (This kind of thing happened in real life, for example when mobs turned on prominent people who had supported the French revolution--such as the scientist Joseph Priestley.)

Romantic quadrangle

Romantic quadrangleClarissa, leaving the wreck of her mansion behind to be renovated, takes Mary with her and follows Walwyn to Sussex, even though it’s his friend Frederic that she’s really seeking after.

Mary can no longer hold in her dismay at Clarissa’s conduct when they are escorted into the army barracks at Horsham and the soldiers promptly surround them and start leering at them. She runs into a room which turns out to be a sickroom, thus exposing herself and Clarissa to contagion. Clarissa removes them both to a local inn and takes to her bed, convinced that she is going to expire of fever, even though the local doctor assures her that she’s fine. When Captain Walwyn comes to call upon her, Mary remonstrates with her for even thinking of receiving a gentleman while she’s lying in bed, and Clarissa turns on her: “If I could have foreseen what [Mary’s late father] Mr. Cuthbert imposed upon me, worlds should not have tempted me to have undertaken the charge of a person, who, like a baneful planet, interposes to shroud my destiny with malign influence! Miss Cuthbert, I will see my friend. What! Are all our hours of confidence as nothing? Are the sweet interchanges of sentiment to be forgotten? And shall I discard a rooted and cemented friendship, like ours, to please a prudish girl…”

Captain Walwyn, understandably, assumes that Clarissa is in love with him, and he is looking forward to marrying an heiress. Meanwhile, Mary falls dangerously ill with a fever, but Clarissa is too selfish to stay and nurse her. She abandons her in the care of the local doctor and a nurse and takes off to see Frederic Montgomery at his family's parsonage. More farcical misunderstandings ensue between Frederic and Clarissa.

Covent Garden fire, British Museum Truth and consequences

Covent Garden fire, British Museum Truth and consequencesFrederic is horrified when he realizes Clarissa has abandoned Mary, deathly ill, in a strange town and summons her Aunt Deborah to her aid. Mary recovers while Clarissa, humiliated, retreats to London where she dies spectacularly in a real-life event, the Covent Garden Theatre fire of September 1808. Mary inherits everything and marries Frederic. The principles of propriety and religion triumph.

Female Education

Miranda Kiek notes that The Corinna of England blames Clarissa’s untoward behaviour on a faulty education and upbringing. "Anti-Jacobin fiction, especially when aimed principally at female readers, often blurs into educational treatise. Amelia Alderson Opie, Elizabeth Hamilton, and Jane West, who were all publishing novels around that time that were aimed at a similar market to that of The Corinna of England, never failed to exhaustively detail the minutiae of their heroines’ educational background.”

This again, tracks with Mansfield Park, which emphasizes the superficial education received by the Bertram girls and the consequent disaster for Maria Bertram Rushworth. Too late, their father Sir Thomas realizes that fundamental training in good principles was missing.

Madame de Stael costumed as her creation Corinne, by Massot (detail) Reviews of The Corinna of England

Madame de Stael costumed as her creation Corinne, by Massot (detail) Reviews of The Corinna of EnglandCorinna was given a favourable review in the Flowers of Literature, which is not surprising considering that the Flowers of Literature was published by Benjamin Crosby, the publisher of Corinna: “a most ingenious and successful satire against the votaries of what is erroneously called sentiment, and of the new school of philosophy. Corinna is a strong caricature, but is sketched with a masterly hand, and her eccentricities will excite alternate laughter and surprise. The visit to the horse barracks, the equivoque between the heroine and Walwyn, and the embarrassing scene before the Montgomery family are excellently managed; and while the author so strikingly evinces her power of ridicule, she no less proves her skill in striking the chord of sympathy; the characters of Mary Cuthbert and of Montgomery, being delineated with the greatest delicacy, Good sense and ability pervade throughout."

About the authoresses

Since the authorship of this novel is not confirmed, I will save my thoughts on that for a future date. Some of the other disputed books I've read so far: “The Winter in Bath,” “The Woman of Colour,” “Light and Shade", and "Black Rock House."

Germaine de Stael (1766-1817), daughter of the finance minister under Louis XVI, survived the fall of the ancien regime, the Reign of Terror, and the rise and fall of Napoleon, but much of it from a safe distance in exile. Like her creation Corinne; her considerable intellect could not be restrained by traditional gender expectations. It was reported that Jane Austen, when in London, had an opportunity to meet Madame de Stael, but turned it down. Kiek, Miranda. “Celebrity--thou art translated! Corinne in England” in Celebrity Across the Channel, 1750–1850. Eds Anais Pedron and Claire Siviter. U of Delaware Press, 2021. For me, Kiek's insights on the similarities between Mansfield Park and Corinna of England underscore the value of understanding Austen's masterpieces in context. When we read them in isolation, we can misinterpret the meaning or intent of things written more than 200 years ago.

Sylvia Bordoni's foreword to the Chawton House 2015 modern edition of The Corinna of England explains more about how Corinna of England is a parody of Corinne.

Previous post: Agatha and The Phantom Next post: A 100-year-old review of Mansfield Park

Published on October 22, 2025 00:00

No comments have been added yet.