My review of I Deliver Parcel in Beijing

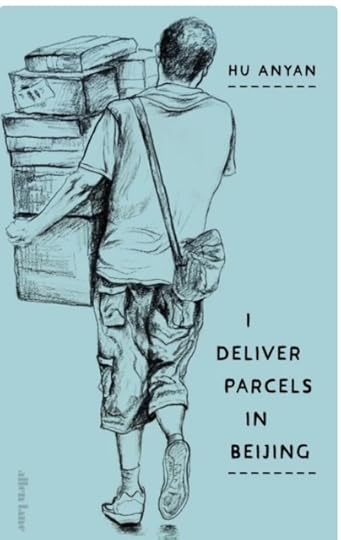

I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyán

I read the first six chapters in one go: I simply couldn’t put it down. The book has a raw authenticity. It recounts Hu Anyán’s years of working in China’s low-wage, high-pressure gig economy. Over two decades, he held 19 different jobs across six cities, from petrol-station attendant, shop assistant, and security guard to night-shift warehouse sorter and courier delivering parcels in Beijing.

Much of the book focuses on his time as a courier in the capital around 2018–19: twelve-hour days, a delivery every few minutes, earning only fractions of a yuan per parcel. He navigates endless construction sites, broken e-bike batteries, angry customers, and relentless competition among co-workers.

I was fascinated by his account. I knew life as a delivery worker was hard, but I hadn’t realised just how gruelling it could be. Hu writes in a reflective, often deadpan tone, describing the physical toll (“I sweated so much I never needed to pee”), the psychological strain, and the small moments of dignity amid drudgery. I was shocked by how many clients, mostly urban dwellers, treated him with contempt, even filing complaints over minor mistakes. In one case, a customer accused him of theft despite clear photo evidence that he had left the parcel in the designated locker. The company still deducted the item’s value from his wages while the case was being “investigated.”

Despite these vivid details, my enthusiasm dimmed as the book went on. The writing becomes repetitive, and the momentum falters. The narrative is divided into two main parts — his time as a courier and his earlier work experiences — but it lacks a dramatic arc. If I were to edit it, I’d weave the earlier stories through the main narrative rather than grouping them at the end.

When Hu eventually quits the delivery job, a few clients send him thank-you messages on WeChat, one calling him “the best delivery man.” That moment — simple yet profound — would have made a perfect ending, symbolising his craving for human recognition in an inhuman system. The prose isn’t great literature, but it contains flashes of brilliance: “Time is money, but money also devours time.”

“No one tells you that freedom in the gig economy means you are free to collapse whenever you like.”

Over all, I really enjoy reading this book. I Deliver Parcels in Beijing isn’t just about couriers or exploitation; it’s about the universal human desire for dignity and control over one’s own life, a quest for freedom that feels ever more elusive in a world ruled by speed, data, and invisible bosses.

Hu Anyán is deeply preoccupied with freedom, both as an idea and as a lived contradiction. I hope his newfound recognition as a writer and no doubt improved financial situation have granted him some measure of freedom at last, especially the spiritual kind.