KC Masterpiece

warning: there’s some rough language in this post.

Is the barbecue sauce my first association with Kansas City?

KC Masterpiece is a barbecue sauce that is marketed by the HV Food Products Company, a subsidiary of the Clorox Company

It was invented by Rich Davis, a child psychologist and former Dean of the University of North Dakota Medical School, who also experimented with “mustchup,” a mustard ketchup combo.

Kansas City became famous in song as a party town. The Beatles sing about it:

“Kansas City” was written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, two nineteen-year-old rhythm and blues fans from Los Angeles. Neither had been to Kansas City, but were inspired by Big Joe Turner records.

from Big Joe Turner’s Wikipedia page:

At that time Kansas City nightclubs were subject to frequent raids by the police; Turner said, “The Boss man would have his bondsmen down at the police station before we got there. We’d walk in, sign our names and walk right out. Then we would cabaret until morning.”

Why Kansas City?:

In the 1930s, Kansas City was very much the crossroads of the United States, resulting in a mix of cultures. Transcontinental trips by plane or train often necessitated a stop in the city. The era marked the zenith of power of political boss Tom Pendergast. Kansas City was a wide open town with prohibition era liquor laws and hours totally ignored, and was called the new Storyville. Most of the jazz musicians associated with the style were born in other places but got caught up in the friendly musical competitions among performers that could keep a single song being performed in variations for an entire night.

so says the Wikipedia entry “Kansas City Jazz.”

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, when Kansas City was a hotbed of jazz activity, Mr. McShann was in the thick of the action. Along with his fellow pianist and bandleader Count Basie, the singer Joe Turner and many others, he helped establish what came to be known as the Kansas City sound: a brand of jazz rooted in the blues, driven by riffs and marked by a powerful but relaxed rhythmic pulse.

“You’d hear some cat play,” he told The Associated Press in 2003, “and somebody would say, ‘This cat, he sounds like he’s from Kansas City.’ It was Kansas City style. They knew it on the East Coast. They knew it on the West Coast. They knew it up north, and they knew it down south.”

Jay McShann obituary.

from a pretty interesting 1948 article in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, “The Myth of hte Wide-Open City,” by Virgil W. Peterson:

In 1933 Tom Pendergast openly boasted that while gambling and slot machine complaints might be frequent, Kansas City afforded its citizens greater protection from violence and crime than any other American city. But that was only the usual prating of a machine boss. The die had been cast,-wide-open

gambling, always a chief pillar of organized crime and political corruption, had resulted in powerful alliances between officialdom and the underworld. Kansas City had become the most wideopen town in the United States,-a haven for the toughest gangsters from every part of America. The officials who had

utilized the underworld in maintaining political dominance had created a monster they could no longer control. The underworld was completely out of hand. In May, 1933, the daughter of the city manager, Henry F. McElroy, was kidnaped. John Lazia, the gangster, took over the task of raising the ransom money. She was released. On the morning of June 17, 1933, a brazen attempt was made to liberate the notorious bank robber and escaped federal prisoner, Frank Nash, who had been captured and was being returned to the federal penitentiary. As officers emerged with Nash from the Kansas City Union Station, machine guns blasted forth. Five persons were killed, including two members of the Kansas City Police Department, a special agent of the FBI, a chief of police from Oklahoma and, ironically, Frank Nash himself. Two other officers were wounded. The massacre had been engineered by the outlaw, Vern C. Miller, who had been placed in touch with the killers, Pretty Boy Floyd and Adam Richetti, by the gambling czar John Lazia. In July, 1933, the kidnaping of the wealthy Charles F. Urschel in Oklahoma attracted nationwide attention. Ransom money paid in the case was traced to a prominent Kansas City criminal gang. In the same year a lieutenant of John Lazia attempted to kill Sheriff

Thomas B. Bash.

In the March, 1934, election, fraud was rampant and it was conducted in Hitler fashion. Four people were killed and eleven seriously injured in election violence. The attention of the entire United States was focused on Kansas City. The United States Senate announced its intention to conduct an official investigation. John Lazia was then recognized in Kansas City as one of its most influential and powerful political figures. A short time later, on July 10, 1934, John Lazia fell in a hail of gangland bullets. Tom Pendergast’s chief lieutenant and gambling overlord was dead. And, ironically, the gun which fired the fatal bullets had been used a year earlier in the Union Station massacre in which Lazia had figured. Kansas City still had to endure five years of the “rule of ruin” before Tom Pendergast was committed to the federal penitentiary May 29, 1939. Unfortunately, the story of the Pendergast machine is not the story of Kansas City alone. Disgracing the pages of American political history, comparable stories are recorded of many of our large municipalities.

Peterson argues that “wide open city” method – letting the gangsters get away with their vices in exchange for keeping murder outside of the cities – didn’t work. I don’t know if it was ever really intended to, seems like bullshit the likes of Pendergast invented so they could justify the profitable vices and criminal alliances.

While it may not have worked for keeping order, the wide open city did seem to lead to a raucous music scene. The greatest Kansas City jazzman has got to be Charlie Parker.

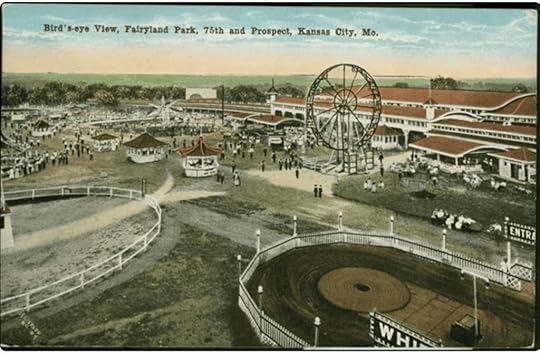

In 1940, he returned to Kansas City to perform with Jay McShann and to attend the funeral of his father, Charles Sr. The younger Parker then spent the summer in McShann’s band playing at Fairyland Park for all-white audiences; trumpet player Bernard Anderson introduced him to Dizzy Gillespie.

(source)

You won’t have a bad time if you go to Spotify or YouTube and put on Charlie Parker Radio as you read the rest of this post.

Music and violence still seem to intersect in Kansas City. Mac Dre was shot and killed there:

After Hicks and other Thizz Entertainment members had performed a show in Kansas City, Missouri on October 31, 2004, an unidentified gunman shot at the group’s van as it traveled on U.S. Route 71 in the early morning hours of November 1. The van’s driver crashed and called 911, but Hicks was pronounced dead at the scene from a bullet wound to the neck.[13] Local rapper Anthony “Fat Tone” Watkins was alleged to have been responsible for the murder, but no evidence ever surfaced, and Watkins himself was shot dead the following year.

Although maybe there’s one of those in every city if you go digging.

Before Pendergast, Kansas City was already wild. From David McCullough’s Truman, describing Kansas City around 1900:

It. was a wide-open town still, more than living up to its reputation. Sporting houses and saloons far outnumbered churches. “When a bachelor or stale old codger was in sore need of easing himself [with a woman], he looked for a sign in the window which said: Transient Rooms or Light Housekeeping,” remembered the writer Edward Dahlberg, whose mother was proprietor of the Star Lady Barbershop on 8th Street. To Dahlberg, in memory, nearly everything about the Kansas City of 1905, the city of his boyhood, was redolent of sex and temptation. To him it was a “wild, concupiscent city.” Another contemporary, Virgil Thomson, who was to become a foremost composer, wrote of whole blocks where there were nothing but saloons, this in happy contrast, he said, to dry, “moralistic” Kansas across the line. “And just as Memphis and St. Louis had their Blues, we had our Twelfth Street Rag proclaiming joyous low life.” But with such joyous low life Harry appears to have had little or no experience. Years afterward, joking with friends about his music lessons, he would reflect that had things gone differently he might have wound up playing the piano in a whorehouse, but there is no evidence he ever set foot in such a place, or that he “carried on” in Kansas City in any fashion.

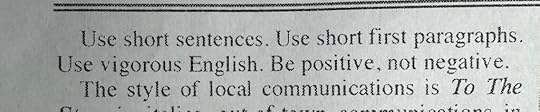

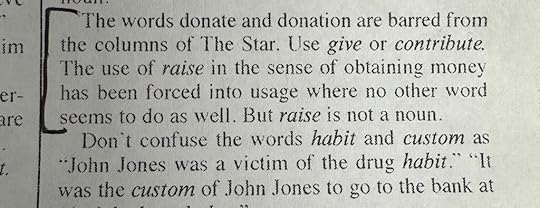

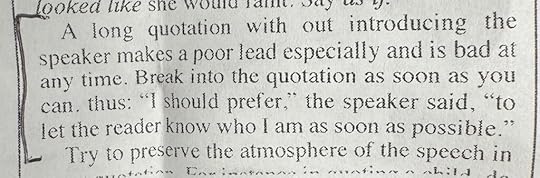

Young Ernest Hemingway was a reporter for The Kansas City Star in 1917-1918, when he was roughly 17-18. Hemingway biographers and documentarians like to point out the influence of The Kansas City Star style sheet, which begins:

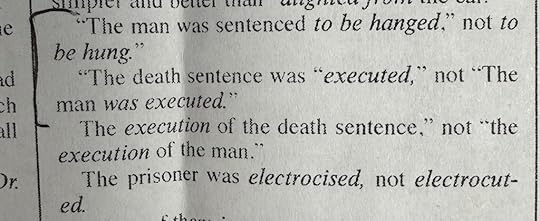

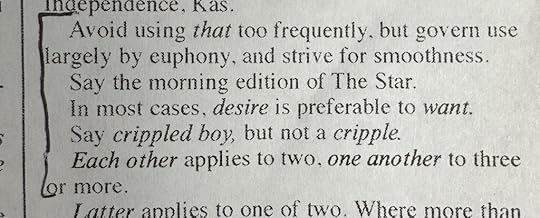

but it also has a bunch of stranger rules:

I’m glad I printed it out, it used to be online at the Kansas City Star’s website but the link appears dead.

An interstitial section in in our time contains a Kansas City story fragment:

At two o’clock in the morning two Hungarians got into a cigar store at Fifteenth Street and Grand Avenue. Drevitts and Boyle drove up from the Fifteenth Street police station in a Ford. The Hungarians were backing their wagon out of an alley. Boyle shot one off the seat of the wagon and one out of the wagon box. Drevetts got frightened when he found they were both dead.

Hell Jimmy, he said, you oughtn’t to have done it. There’s liable to be a hell of a lot of trouble.

—They’re crooks ain’t they? said Boyle. They’re wops ain’t they? Who the hell is going to make any trouble?

—That’s all right maybe this time, said Drevitts, but how did you know they were wops when you bumped them?

Wops, said Boyle, I can tell wops a mile off.

15th and Grand? 15th is now Truman Road.

In Across the River and Into the Trees, Hemingway’s Colonel Cantwell tells his young Italian mistress about the Muehlebach Hotel. They’re fantasizing about an American road trip?

‘Do you mind being here out of season?’

‘Did you think I was a snob because I come from an old family? We’re the ones who are not snobs. The snobs are what you call jerks and the people with all the new money. Did you ever see so much new money?’

‘Yes,’ the Colonel said. ‘I saw it in Kansas City when I used to come in from Fort Riley to play polo at the Country Club.’

‘Was it as bad as here?’

‘No, it was quite pleasant. I liked it and that part of Kansas City is very beautiful.’

‘Is it really? I wish that we could go there. Do they have the camps there too? The ones that we are going to stay at?’

‘Surely. But we’ll stay at the Muehlebach hotel which has the biggest beds in the world and we’ll pretend that we are oil millionaires.’

‘Where will we leave the Cadillac?’

‘Is it a Cadillac now?’

‘Yes. Unless you want to take the big Buick Roadmaster, with the Dynaflow drive. I’ve driven it all over Europe. It was in that last Vogue you sent me.’

‘We’d probably better just use one at a time,’ the Colonel said. ‘Whichever one we decide to use we will park in the garage alongside the Muehlebach.’

‘Is the Muehlebach very splendid?’

‘Wonderful. You’ll love it. When we leave town we’ll drive north to St. Joe and have a drink in the bar at the Roubidoux, maybe two drinks and then we will cross the river and go west. You can drive and we can spell each other.’

‘What is that?’

‘Take turns driving.’

‘I’m driving now.’

‘Let’s skip the dull part and get to Chimney Rock and go on to Scott’s Bluff and Torrington and after that you will begin to see it.’

‘I have the road maps and the guides and that man who says where to eat and the A.A.A. guide to the camps and the hotels.’

‘Do you work on this much?’

‘I work at it in the evenings, with the things you sent me. What kind of a licence will we have?’

‘Missouri. We’ll buy the car in Kansas City. We fly to Kansas City, don’t you remember? Or we can go on a really good train.’

from Wikipedia. The windowless section is an addition. It’s now part of the downtown Marriott, and it sounds like you’d struggle to find anything of what the Colonel remembers.

They imploded the 1952 Muehlebach Tower annex building and in 1998 built a new, modern Muehlebach tower in its place. A “skybridge” was also built that connects both hotel buildings on their second floors. The original 1915 Muehlebach building’s lobby and ballrooms were restored and are now used as banquet and convention facilities by the Marriott. The original hotel guest room floors above have been gutted and remain unused.

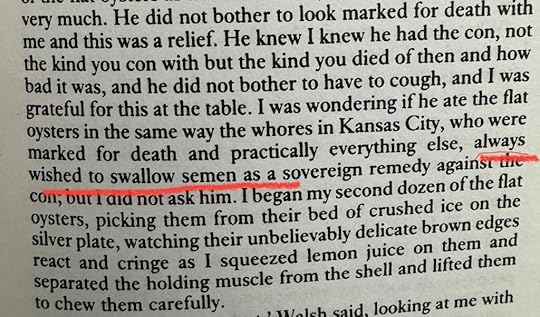

In A Moveable Feast, published posthumously but written around 1960, a sickly fellow in Paris makes Hemingway reminsce:

Some RFK Jr. type thinking..

Back when we were learning about Savoy Special, we came across the Savoy Hotel of Kansas City:

It’s now the Hotel Savoy Kansas City, Tapestry Collection by Hilton. I’d at least check this place out on a next visit.

On my first trip to Kansas City, around 2009, stopping in for a night on a transcontinental train trip, I stayed at the Sheraton Crown Center, formerly the Hyatt Regency, which was famous for a disastrous walkway collapse that killed 114 people. Some grim photos there tell the story and also evoke the era, when hundreds of people would attend a “tea dance.”

Kansas City is famous for barbecue, specifically a style that’s just some meat with a sweet sauce.

Kansas City–style barbecue is a slowly smoked meat barbecue originating in Kansas City, Missouri in the early 20th century. It has a thick, sweet sauce derived from brown sugar, molasses, and tomatoes. Henry Perry is credited as its originator, as two of the oldest Kansas City–style barbecue restaurants still in operation trace their roots back to Perry’s pit.

Those would be Arthur Bryant’s (subject of a New Yorker piece by Calvin Trillin) and Gates B-B-Q. There’s also Jack Stack, Oklahoma Joe’s now Joe’s, and more.

Henry Perry himself was from Memphis:

He had a sign in his restaurant that said “my business is to serve you, not to entertain you,” and it was known for its far-reaching BBQ smells. He was known for his generosity, and would often give food to people for free.[1]

He later moved a few blocks away within the neighborhood of 19th and Highland, where he operated out of an old trolley barn throughout the 1920s and 1930s when the neighborhood became famed for its Kansas City Jazz during the Tom Pendergast era.

Customers paid 25 cents for hot meat smoked over oak and hickory and wrapped in newsprint. Perry’s sauce was described as “harsh, peppery” (rather than sweet). Perry’s menu included such barbecue standards of the day as beef and wild game such as possum, woodchuck, and raccoon.

“Is Kansas City Still The Barbecue Capital of America?” asked a recent NY Times article.

According to Mr. Gates, the meats at a Kansas City barbecue joint historically all had one thing in common: They were cheap.

Cooking inexpensive cuts low and slow is the foundation of every American barbecue tradition, but Kansas City had an advantage — one of the largest stockyards in the country. “Brisket was practically a giveaway,” Mr. Gates said. Abundance inspired new ideas: Burnt ends, a signature of Kansas City barbecue, began as overcooked brisket edges that Arthur Bryant’s cooks chopped up and gave away to customers.

The stockyards never fully recovered from a devastating flood in 1951 and closed permanently in 1991.

More on the West Bottoms floods:

(is that a dead cow? why do I feel sad for this drowned cow, when his fate was doubtless grim in any case?)

Both times I’ve been to Kansas City I transited through the grand Union Station:

I ate all the barbecue, went to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum, walked the Power & Light District when I went there alone. When I went there with my wife, again a brief stop before a train trip, we looked at the Christmas lights on Country Club Plaza, and we had a KC strip steaks in the West Bottoms.

The Kansas City of reality didn’t quite match the myth. That might be my fault, who knows. If I ever get back, I’d like to visit the Nelson- Atkins Museum, and see Bosch’s Temptation of St. Anthony:

The other day on my plane back from New Jersey I looked out the window and saw Kansas City below me. There was Arrowhead Stadium and Kauffman Stadium, and the surrounding car-consumed wasteland:

it’s too bad there wasn’t a game on. I could’ve seen a tiny Travis Kelce and a tiny Patrick Mahomes.