Reintroducing Justice Robert Jackson

Reintroducing Justice Robert Jackson

In 1952, Justice Robert Jackson issued a concurring opinion in the case of Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, in which a majority of the Supreme Court held that President Harry Truman could not invoke executive power to seize several of the major U.S. steel manufacturing companies in order to prevent a nation-wide steel strike that the Truman administration claimed would disrupt the participation of the United States in the Korean war.

Jackson’s opinion in Youngstown sketched a framework for executive power under the Constitution, identifying three examples of executive decisions against the backdrop of congressional authority. He set forth a continuum of executive power, ranging from instances in which executive decisions were “conclusive and preclusive” of the authority of other branches, to ones in which Congress and the executive shared powers and the branches operated in a “twilight zone” of concurrent authority, to ones in which an executive decision was in contradiction to a congressional effort to restrain it. When Jackson’s opinion appeared it garnered some appreciative commentary in academic circles but did not otherwise attract much attention.

Jackson’s Youngstown concurrence was revived, however, in two memorable opinions in American constitutional law and politics. The first was United States v. Nixon, in which Chief Justice Burger quoted a statement by Jackson that the dispersion of powers among the branches of government by the Constitution was designed to ensure a “workable government.” Burger concluded that allowing President Nixon to assert executive privilege against a subpoena in a criminal proceeding merely on the basis of a “general interest in confidentiality” would gravely interfere with the function of the courts and render the government “unworkable.” The second was Trump v. United States, in which Jackson’s statement in Youngstown that in some instances the president’s power to make executive decisions was “conclusive and preclusive” was used by Chief Justice Roberts to show that granting presidents absolute immunity for their official acts was necessary to enable them to execute their duties fearlessly and fairly.

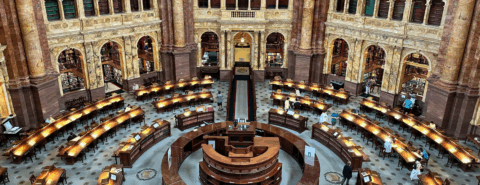

More than seventy years after Jackson issued it, his Youngstown concurrence remains the most authoritative statement of the scope of executive power under the Constitution. But what of the justice who issued that opinion? Robert Jackson was arguably one of the most influential persons in the mid twentieth-century legal profession and a unique figure in American legal history. Yet today he is not widely known and has in some respects been misunderstood. Despite his having one of the largest collections of private papers in the Library of Congress, there has been comparatively little scholarship or popular writing devoted to Jackson. It is time to reintroduce him.

Jackson was the last Supreme Court justice to have entered the legal profession by “reading for the law,” a process where people apprenticed themselves to law offices prior to taking a bar examination. He would eventually study law for one year at Albany Law School and receive a degree, but he never attended college. His family were dairy farmers in western Pennsylvania and New York, and he was the first in his family to pursue a legal career. By 1934 he had become one of the more successful lawyers and wealthy residents in Jamestown, New York.

That year Jackson was approached by members of the Franklin Roosevelt administration and recruited to join the Bureau of Internal Revenue, even though his practice had not included tax law. From that position he progressed rapidly through New Deal agencies, becoming Solicitor General of the United States in 1938 and Attorney General in 1940. By that year he was on the short list for Supreme Court appointments, and was nominated to the Court by Roosevelt in 1941.

Jackson seemingly had every quality necessary to be an influential Supreme Court justice, possessing exceptional analytical and forensic skills and being a gifted writer. But he ended up somewhat unfulfilled on the Court, chafing about its isolation from foreign affairs during World War II and having fractious relationships with some of his fellow justices, notably Hugo Black and William O. Douglas. In the spring of 1945, he was offered the position of chief counsel at the forthcoming Nuremberg trials and took leave from the Court, uncertain about whether he would return. Jackson was largely responsible for the format of the trials, and although he had numerous difficulties with representatives of the other allied powers prosecuting Nazi war criminals, especially those from the Soviet Union, he said in his memoirs that he regarded his time at Nuremberg as the high point of his experience.

Jackson’s two years at Nuremberg were also a time in which he began an amorous relationship with his secretary, Elsie Douglas, to whom he would eventually leave his extensive private papers in his will. Douglas continued as his secretary when Jackson returned to the Court after Nuremberg, and when Jackson suddenly died of a heart attack in October 1954, it was in Elsie Douglas’ apartment. After Jackson’s return to the Court in 1946 his relations with colleagues improved, and his last major participation in a Court case came with Brown v. Board of Education in the 1952 and 1953 terms, in which Jackson, through writing successive memos to himself, eventually joined the Court’s unanimous opinion invalidating racial segregation in the public schools. Jackson had a heart attack in March 1954 and only returned to the Court on the day the Brown case was handed down. He then sought to recover over the summer of 1954, only to succumb that October.

All in all, a memorable life and career and a fascinating, complicated personality, whose remarkable talents somehow did not quite suit him for the role of a Supreme Court justice.

Featured image by Abdullah Guc via Unsplash.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers