[COPY] Wormwood

Don’t you hate it when you say (or write) something that you believe is irrefutably wise, and someone says, “But what about…?”, and you are either forced to concede their annoying (but correct) position, or you defensively reject that rebuttal as some version of “balderdash”?

I remember at a critical moment in my own life, while blathering away in the company of a therapist as I was going through a painful divorce, I shouted rage at my parents for the harsh, rigid manner in which I was raised. In a heartbeat, I transferred that righteous rage to my soon-to-be ex-wife, exclaiming that I had married my unresolved issues with my parents. “What a breakthrough!” I thought. “Nailed it. I’m cured. I’m whole now. The rest of my life will be a breeze.”

Sadly, no. That was only the beginning. No sooner had I moved out of the house than I was getting daily phone calls from those very flawed parents almost every evening, wondering how I was doing. They offered to help me out with money -- whatever I needed.

I started to think, “Where were these thoughtful parents when I needed them, when I was a child, a teenager?” Moved as I was by their continuing concern about my well-being now that I was living on my own, my arrogant defenses collapsed, and I realized they were there. They were always there.

As I was growing up, I resented the rules and regulations of my childhood; yes, the physical punishments – the smacks, the straps; the forced attendance at Catholic schools that augmented the rough stuff with religious and emotional indoctrination. I bristled at the darker memories and developed a reservoir of resentment that shaped much of my thinking and behavior.

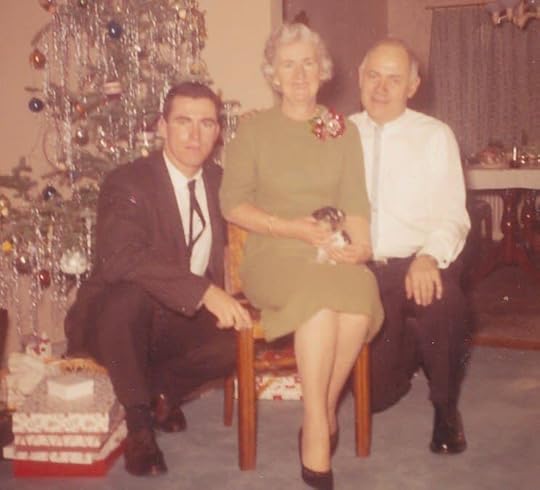

Late, but luckily not too late, I recognized how good and generous my mother and father were in their hearts. I began to realize that they did the best they could as parents, especially given their own childhoods. My father, Bill Sr., was born poor in Harlem in 1914. His mother died when he was nine-years’ old, and he developed a stammer that took years to control. He and his brother were bullied in school when they moved to Queens. My father didn’t like being bullied, so he went into training as a gymnast and a boxer. The bullying soon stopped. My father learned early in life that if he was going to amount to something in life, he would have to take control, first of himself, then of his circumstances. He had no patience with people, including his two sons, who didn’t have that same degree of fortitude.

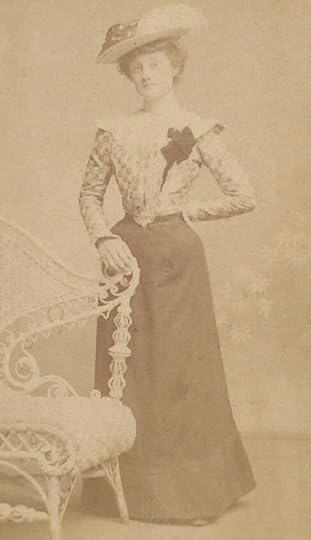

My mother, Margaret, was one of ten children born to Thomas and Mary Hanlon. As a child, she lived in a series of squalid apartments in “Hell’s Kitchen,” a perennial Irish ghetto on the west side of Manhattan – a “series” of apartments because the family kept moving almost annually as it got bigger…and bigger. The family kept getting “bigger” because Tom and Mary were devout Catholics and were told by the Church that it was their Christian duty to “go forth and multiply” and any use of condoms was a mortal sin. My grandparents believed that if one or the other (or both) died in “the act” while my grandfather was wearing a condom, they would both spend eternity in hell.

Presto! Ten children.

My mother slept in a bedroom with her three sisters. As the youngest, she wore hand-me-downs till she was old enough to start making her own clothes. My mother was a smart, beautiful woman. But because the family needed money, she dropped out of school at age fourteen to contribute to the household. When they moved to Queens (where she met my father) they were able to live as “Lace Curtain Irish” because everyone in the family had a job, and everyone contributed to the family fund. And when three of the six sons were in the service during WWII, they sent money home to their parents.

As children, my brother and I would make light of their tales about how tough they had it compared to us. But gradually after my divorce, I re-examined those tales. Clearly my parents were not trained in the finer points of child-rearing. They were trained in deprivation and survival, and they were determined that my brother and I would have the will, the wherewithal, and independence to avoid deprivation and to survive. They succeeded, though it was sometimes a bumpy ride.

So, although I always loved and respected my parents, I was late in appreciating the pain of their experience and the depth of their character. By the time both of my parents contracted Alzheimer’s in their late seventies, I had learned from them something of what poet Robert Haydn called “love’s austere and lonely offices,” and I was honored to return my parents’ caring for me by caring for them in every possible way in their time of need.

Psychologists tell us this love/hate nexus is a common human phenomenon but wrestling with that ambiguity when it takes residence in the “rag and bone shop” of your own heart can be difficult.

For Bill and Margaret Shaw, I give thanks.