Special Guest Post: Melusine, My Lucky Charm, by Justine Brown, Author of by Mary of Modena: James II’s Dazzling Queen

Available from Amazon UK and pre-order from Amazon US

The 1688 “Glorious Revolution” that toppled James II and VII also veiled his consort in propaganda. Mary of Modena: James II’s Dazzling Queen reveals the extraordinary woman beneath. Lovely and spirited, Mary Beatrice Isabella d’Este is also England’s sole Italian queen

Melusine, My Lucky Charm

Melusine Fontaine

As part of my research for my new book, Mary of Modena: James II’s Dazzling Queen, I was fortunate enough to travel to the Stuart consort’s birthplace in northern Italy. At this stage I was keenly intrigued by this lovely Italian lady, but felt I did not yet know her well enough to tell her tale.

My husband and I flew first to nearby Bologna; we then boarded a train to Modena. Alighting at the station, we began to make our way through the beckoning maze of streets towards the centre of town, questing for two key sites.

The first was the graceful pale stone Baroque palazzo ducale (duke’s palace) where Mary—or Mary Beatrice as I took to calling her, so as not to confuse my subject with her step-daughter, Mary II—was born and raised. The second site was the medieval duomo (cathedral) di Modena. Touring the great palazzo, which today functions as an officer training facility for the Italian military, I was able to ‘meet’ Mary Beatrice on the imaginative plane.

A pious and thoughtful young principessa of the House of Este, Mary Beatrice had once yearned to take the veil. Instead, Pope Clement X persuaded her to marry James Duke of York so she could intercede for oppressed English Catholics. A proxy wedding took place at the Palazzo Ducale.

I could grasp something of what she left behind when, in the year 1673, the very young woman departed her home forever to travel to the faraway island of Great Britain. Visiting the palazzo was immensely helpful, but touring the duomo was a revelation.

There I saw the 13th century ‘Artus architrave’ depicting the adventures of King Arthur and his brave knights, which probably formed Mary Beatrice’s expectations of her new home. (She knew next to nothing of contemporary England, but like every other European she was steeped in Arthurian lore.)

And in the crypt I spied, atop the slim stone pillars, carved lions, griffons…and then, with a start of recognition—I beheld a two-tailed water fairy, the mermaid named Melusine. The sight of her reassured me that I was on the right path.

Maestro delle Metope di Modena, Sirena

A writer should have a lucky charm, a talisman, for companionship on the journey. For many years now, Melusine has been mine. The ancient ancestress of Hans Christian Anderson’s Little Mermaid, Melusine inhabits the holy wells of Christendom.

Her story was written down by the French poet Jean d’Arras in the 14th century. It goes something like this: over the English Channel and faraway, in a deep well at the edge of the town of Lusignan, near Poitiers, there swims a beautiful two-tailed water sprite named Melusine.

The daughter of the fairy Pressine and the King of Albany—Scotland-- Melusine is born in human form and grows into a graceful maiden. One day, however, she mistreats her royal father; as punishment, her enchantress mother condemns Melusine to metamorphose into a freshwater mermaid each Saturday.

One day, riding in the forest, Melusine stops to water her horse at a cool fountain. There she encounters the noble Raymondin; they instantly fall in love. He asks for her hand, and she agrees to marry him—on a single condition. One day out of seven, each Saturday, he may not see her at all.

If he so much as glimpses her, he will lose her forever. Raymondin asks no questions, but hastens to accept. Now Melusine makes him blissfully contented. Not only does she adore him, she pulls riches out of thin air for him. She magicks him up a church, where they marry; and a castle, where they live happily together. Day after day, month after month, everything is perfect. She gives him many sons. Together the couple found the noble House of Lusignan.

But the idyll is disrupted when an ill-wisher convinces Raymondin to spy on his wife, claiming that Melusine is entertaining a lover on Saturdays. Peering through the keyhole, Raymondin sees her in her bath, her great green tail flopping out.

He emits a gasp. Melusine, realising what has happened, rebukes him. Transforming into a dragon, she wheels three times around the chateau, crying aloud, and flies away. Melusine has abandoned the castle, cathedral and village to her people, but she herself vanishes from sight. Returning to mermaid form, Melusine returns to her watery home. She can sometimes be heard keening to announce the death of a family member. But that is all.

.Julius Hubner - Melusine

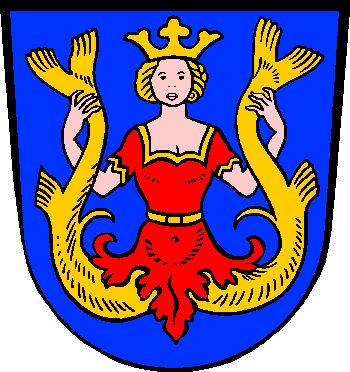

As well as being honoured as the foundress of the noble House of Lusignan, Melusine is claimed by the members of the House of Luxembourg, as well as others. She is featured on several coats of arms. The mermaid is also featured on a medieval badge, which could be worn by members of a noble family’s entourage. Modern replicas are available, and I have one in my possession.

It is noteworthy that the mother of Elizabeth Woodville, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, was particularly proud of her water-fairy lineage. Readers may recall this theme from Philippa Gregory’s White Queen: both Elizabeth and Jacquetta are depicted as practitioners of magic.

The White Queen is of course a novel, but it turns out that the historical Jacquetta did in fact come close to being formally charged with witchcraft in her adopted country of England. The suspicion was that Jacquetta used spells and charms to induce Edward IV to fall in love with her daughter and make her queen. The upshot—Melusine was woven back into the royal family of the British Isles.

Coat of arms of Isen

I happily display my Melusine badge, and she inhabits my screen-saver also. The familiar sight of my favourite freshwater siren —an image of the doubleness of our human nature, of transformation, of enigma—serves as a prompt: it is time to plunge into writing. I believe that in order to get those words out onto the page, we need ritual.

That means habits conducive to composition-- certain sights, sounds and even scents. In my experience, writing can happen only between certain hours; a portal opens, and for a time an alchemical process can occur.

Before it shuts again, the fruits of research—the memories of a voyage to Modena, images of portraits and maps, notes compiled from long hours of poring over books and articles, scraps of poetry, music of the time—can begin to transform into a manuscript, a thing in itself. It seems to me that Melusine oversees the whole mysterious process.

Justine Brown

# # #About the Author

Justine Brown lives in London with her husband, and is the author of several books on a Utopian theme, as well as The Private Life of James II. Born in Vancouver, Canada, Justine travelled widely from a young age. She holds an M.A. in English literature from the University of Toronto, where she developed a broad interest in seventeenth century culture. There she became a Junior Fellow of Massey College. The author of three Utopian-themed books, she runs a YouTube history vlog, Justine Brown’s Bookshelf. Find out more from Justine's website and follow her on Twitter @brown_bookshelf