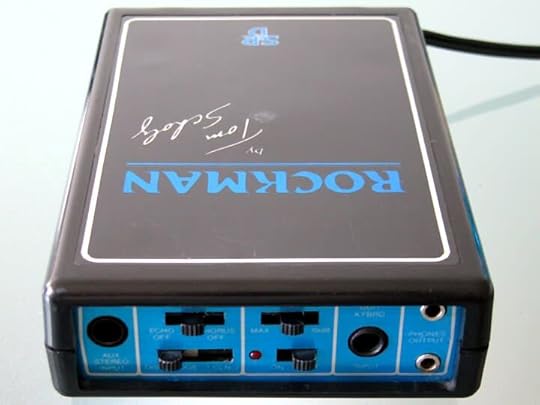

The First Rockman

In the early 1980s, Tom Scholz was trying to package the growl of his guitar into a box the size of “a peanut butter sandwich,” as he later put it. Scholz, who had trained as a mechanical engineer at MIT, had been building his own gear for years, including the Power Soak, but this was a whole other level of complexity.

To pull it off, he brought in Neil Miller, an electrical engineer. The result was the Rockman, a headphone amplifier that would redefine the sound of arena rock and, for a time, bankroll Scholz’s independence from his record label.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of my interview with Miller last year on how the Rockman came to be.

I’ve always been a musician and an engineer. After college, I went out on the road, playing in bands. When I came back to Boston, I had a job working for an audio repair, installation, and sales operation. One of their clients was Tom Scholz, and he was looking for an engineer to help him with a project.

I remember hearing “More Than a Feeling” on the radio in the 70s, but my musical stuff wasn’t so much in the world of rock, so I didn’t pay that much attention to it. I also knew he used to be an engineering student at the same school I went to [MIT], but I didn’t know him there. I figured, well, it was just some guy, so I’ll go talk to him.

I met with him in Weston. They had a little operation—three or four people—working in an attic above a hardware store. It was low-key. There wasn’t anything imposing about it. I sat down and talked to him. He seemed like a pretty normal guy. I learned later that he’s not normal in most senses of the word, but he’s definitely approachable. He wasn’t into the trappings of the rock business. He drove, like, a ten-year-old car for twenty years.

He showed me a chunk of styrofoam that I think had been painted with shoe polish or something. The idea was to mimic the sound of a tube amplifier. Jimi Hendrix had figured it out the old way: you crank a huge amp and let feedback sustain the string forever.

Tom had evolved that into a very controlled tone. In his recordings, he overdubbed everything. It wasn’t spontaneous. It was extremely meticulous. He recorded all the guitar parts himself. Almost one note at a time. That’s how those first albums were made. Two guitars playing leads in harmony.

His idea was to take the sound he had developed in his studio and try to put it in this little box. We would have to squeeze an awful lot into that box. There was compression, a lot of EQ in not the usual places in the signal chain, and a distortion circuit.

There were new integrated circuits coming from Panasonic that made it possible to do a quasi-reverb and a chorus effect. We’d sit there and hit one note on his guitar and listen to it for thirty seconds as it decayed, just to hear how it sounded at the very end.

We actually couldn’t quite squeeze it in—we had to make the box bigger by about half an inch. At the time, it was pretty much state of the art for what you could do with electronics to get guitar sounds. When you listened on headphones, you actually had stereo, which made it sound pretty amazing.

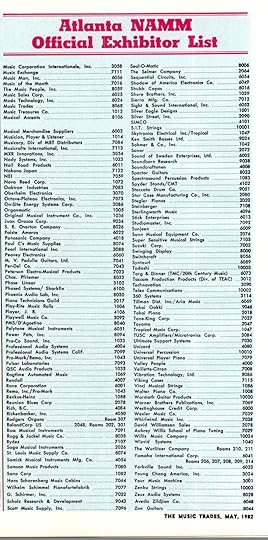

The first trade show was a National Association of Music Merchants show in Atlanta in the summer of 1982. We had one prototype. Maybe two. That was it. All the wires were stuffed inside. If you unscrewed it, everything would pop out like a jack-in-the-box.

Scholz R&D was in Booth #9042 at the 1982 NAMM Show in Atlanta

Scholz R&D was in Booth #9042 at the 1982 NAMM Show in AtlantaTom did the demo himself. Two headphones. Two seats. The Rockman sitting on a pedestal. Tom sat in one seat, playing guitar. People lined up around the block to put on the headphones. After a couple notes, everybody had the same expression: their jaw would just drop. They couldn’t believe that sound was coming out of that little box. People would pick it up to see if there were more wires hidden somewhere.

We didn’t sell any for quite a while after that. Tom came back with orders, and then we had to figure out how to build them. Once it came out, people started recording with it immediately. The first live radio broadcast I remember was Rick Derringer. He plugged his guitar straight into the board through a Rockman. It sounded great.

The genius of it was that there were no knobs. Just switches. Four positions. You couldn’t get a bad sound out of it. If you give people too many knobs, it’s easy to make something sound bad. This way, it was impossible.

We ended up making a custom one for Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top. He said he could use any guitar—just go into a pawn shop and get a guitar. Of course, some of that comes down to the guitar player, too.

I worked with Tom for a number of years after that. We moved from that attic to a larger place near Waltham. We spent endless hours listening to tiny changes—changing one capacitor value, listening again. Sometimes we’d go back and forth between two things that sounded exactly the same to me, but he could hear some tiny difference.

Tom could be intense. He worked constantly. Seven days a week. His house was taken over by his studio and workbench. He wasn’t someone who went out partying. Bands would come by—The Cars, other people—but he was focused. Always working.

I joke that I was on the short list of people who didn’t get sued by him. I did have one moment where I was briefly the enemy over a piece of equipment that didn’t work, but it faded. In general, we got along.

What surprises me is that even now I’m not sure anyone has really replicated the sound of the Rockman. There are digital plug-ins that come close, but I don’t know if they’ve actually captured it. If you want to understand it, you really need to hear one. They’re still on eBay.

Power Soak

- Brendan Borrell's profile

- 22 followers