The Zen of Tea

Tea began as a medicine and grew into a beverage. In China, in the eighth century, it entered the realm of poetry as one of the polite amusements. The fifteenth century saw Japan ennoble it into a religion of aestheticism–Teaism. Teaism is a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence. It inculcates purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order. It is essentially a worship of the Imperfect, as it is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.

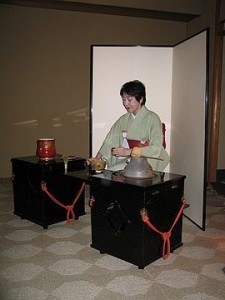

Tea may, of course, be served without any formality. Hot water may be poured over ordinary tea without thought as to the manner in which it is done. But those who practise the art of Cha-no-yu follow a regulated mode of serving with utensils carefully selected and correctly arranged. It is the elaboration of details which gives additional pleasure to the tea-drinker.

Training in the serving and drinking of powdered tea includes nearly all phases of etiquette observed in the Japanese mode of living. For this reason young ladies are encouraged to take lessons in the tea ceremony before marriage. Through this medium they learn correct manners and deportment. Nor is this training useless for older people.

Opening the sliding-door of the service room, the hostess makes a bow before entering the tea-room. It is interesting to observe the elementary lesson of how to bring in the water-jar, which has to be placed in a prescribed position. She leaves the room to reappear immediately, holding the tea-caddy in the right hand and the bowl in the left. She then makes another trip before she sears herself in front of either the stationary hearth, or portable fire-brazier, as the case may be, according to the season.

It would, however, be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to appreciate the fundamental ideals and traditions of Cha-no-yu without knowing something of the philosophy of life and art according to Zen Buddhism.

Meditation and introspection are stressed in the Zen philosophy, and the habit of individual and independent thinking is cultivated. It is natural that the inadequacy of words as vehicles of expression should be recognized. In the mental discipline of Zen, concentration is considered more important than anything else, and devotees are taught to cultivate direct communion with the inner nature of things in order to arrive at truth. The value of suggestion and intuition are therefore emphasized by those who follow Zen traditions.

Cha-no-yu is now a secular pastime, as we have seen. Neither religion nor philosophy has much to do with the cult as it is today. However, the canon of preferring plainness and austere simplicity to elaborate decoration cannot be accounted for except as being of Zen origin.

Paintings in black and white by Zen monks and artists, creating an atmosphere of transcendental calm, are highly prized for their simple, but subtle and suggestive beauty. For the same reason, hanging scrolls bearing inscriptions by the ancient Zen monks are still used for Cha-no-yu parties. The sentiments expressed may be moral or religious, but they are characterized by untrammelled aloofness from dogmas and creeds, and exercise a liberating influence upon the mind. The free and natural strokes of the ideographs, which are different from the more regular styles of the ordinary calligraphers, suggest the writer’s freedom from worldly emotion and passion.

Only a small section of the Japanese people understand the institution of Cha-no-yu, but the common intuition of seeing true beauty in severe simplicity and refined poverty may be considered a racial trait. This characteristic phase of Japanese life may also be traced to the ideals inculcated by the early masters through the medium of the tea ceremony.

With the introduction of Western modes of civilizationJapanhas undergone changes in many directions; the beauty of chaste simplicity is often sacrificed to ugly vulgarism, which characterizes all cheap copies and imperfect adaptations. Nevertheless, the inborn love of simplicity is so deep-rooted that it is discernible, not only in the art and architecture ofJapan, but also in the daily life of the Japanese people. The influence of the tea cult is to be seen in the Japanese home even though nothing be known of ceremonial tea.

Having observed the tea-master’s way of training his pupils, and having taken part in more than one entertainment, the readers will have noted that Cha-no-yu is related to nearly all branches of arts and crafts, as well as to various phases of Japanese home life. It is its many-sidedness that makes Cha-no-yu one of the most interesting aesthetic pursuits.

The love of chaste and refined simplicity, which is the key-note of the Japanese cult of ceremonial tea, has exercised a wholesome influence upon architecture, pottery, landscape gardening etc. For those who are satiated with looking at elaborate, tawdry and pretentious works of art, it is a relief to discover subtle beauty and refinement under an inornate and almost barren aspect. When accomplished tea-masters and devotees give entertainments, they know how to attain artistic effect without depending upon what is colourful and gaudy.

Pottery is perhaps the most important of the industrial arts allied with Cha-no-yu. The ceramic art ofJapanis greatly indebted to tea-masters and devotees for its refined taste, which has inspired artisans. Some knowledge of ceramics is therefore essential for the full enjoyment of a Cha-no-yu entertainment, at which by far the larger part of the utensils are of pottery. Any guest not interested in pottery will disappoint his host. Such a guest invariably fails to appreciate the tea-bowl, caddy, receptacle for fresh water, etc., of which the host is highly and justly proud.

There are builders and carpenters specially trained to build houses for ceremonial tea. In order to appreciate that artistic value of the work of these specialists, one has to acquire the taste for a plain style of architecture. It is natural that a devotee who is about to have his own Cha-no-yu house should make an intensive study by paying careful attention to the minutest details of the building plan.

Nor is the art of landscape gardening less important. The fundamental principles as evolved by ancient masters like Rikyu and Enshu are observed today in laying out new gardens. The deeper our knowledge of the Japanese art of landscape gardening, the greater will be our enjoyment when invited to inspect any garden, even though not connected with Cha-no-yu.

None but a person with an artistic sense strongly developed is capable of arranging flowers in a simple but highly effective way, which is so characteristic of the alcove decoration at a Cha-no-yu party. Should a guest fail to appreciate the vase and flowers arranged in them, his host might never invite him again.

No host would blame those unfamiliar with the Japanese language and literature for their indifference to hanging scrolls bearing inscriptions. A knowledge of textiles will, however, be helpful in appreciating the quality of the ancient brocade used in mounting them.

Devotees of the tea cult are also expected to be connoisseurs of lacquer ware, and those with scanty knowledge of iron and bronze will be incapable of admiring the antique kettles and vases of rare value.

The art of cookery is one of the most important subjects, because the kaisekimeal is served at a regular Cha-no-yu party. Those but slightly interested in the culinary art will make unsuccessful hosts, no matter how superior they may be in their possession of rare works of art. Fastidious epicures who praise an excellent menu might disappoint their host, should they remain insusceptible to the artistic superiority of the china dishes and lacquer bowls selected for the meal.

It will therefore be realized how profound a devotee’s aesthetic pleasure may be, if he makes a study of one subject after another allied with the tea cult, which has exercised a deep refining influence upon the arts and crafts of Japan for hundred of years. It is sincerely hoped therefore that facilities to become more familiar with Cha-no-yu may be extended to those who desire to penetrate more deeply into the cultural life of the Japanese people.

Share on Facebook