Does reading (and learning a language) require two brains?

I love it when a coincidence of listening and reading suddenly starts you thinking; when things kind of come together and actually wake your interest and amaze you (you =me, obviously) all over again with their timeless mystery. What am I talking about? Well a coincidence last week really heightened my interest in an ‘old’ topic.

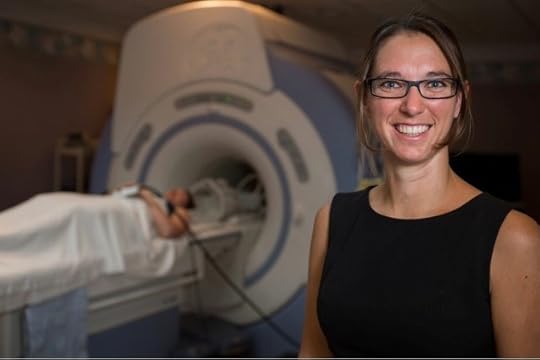

To explain….I was listening the other day (by chance) to a programme called Open Book, and one of the interviewees was a woman called Natalie Phillips (see picture below), a cognitive psychologist who has recently done some research in which subjects were sent through MRI brain scanners whilst reading extracts from Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. My curiosity was aroused because in this 200th anniversary year for Austen’s Pride and Prejudice I have re-read that novel and have enjoyed thinking (for the first time in ages) about the world Jane Austen portrays.

But it was what Phillips says happened in that MRI scanner that really got me going. If I understand it correctly, it goes like this: when her subjects were reading Mansfield Park for pleasure the scanner showed a rush of blood to a certain part of the brain. But when, later, they were shown an extract from the novel which they were asked to analyse (= study/concentrate on), the blood flow increased dramatically – and went to a different part of the same brains. In other words, reading for pleasure and concentrated reading seem (in her research) to be different processes. That’s what I heard her say on the radio – and that is what is also reported here and here.

And this line of thinking coincided, for me, on the same day, with reading David R Hill’s survey review of graded readers in the ELT Journal (Hill, D 2013). Before you read it I need to say that personally I am a huge fan of extensive reading using ‘graded readers’, and have always advocated their use because the more students of a foreign language read in that language, the better they get. (I should disclose that I am hosting the Extensive Reading Foundation awards at IATEL 2013 in Liverpool, so you can see that I mean what I say!).

Anyway.

And like many other methodologists and reading enthusiasts I have always advocated reading for pleasure (aka extensive reading) and trumpeted its superiority over reading for study (aka intensive reading). But in a startling passage of his review, Hill writes:

…….there is tacit support for reading for pleasure and most enthusiasts use this argument to promote ER (extensive reading). I have come to believe this is unfortunate for five reasons. One, most students find reading in a foreign language difficult and not at all pleasurable, certainly at first. Two, students can obtain pleasure more easily in many other ways (mostly related to a screen). Three, aspiring students (and parents) expect to work and not to have fun while they are at school. Four, when entertainment is the foremost reason for reading, publishers, teachers, and students have no focus for selecting titles. Finally, and most important, promoting ER as reading for pleasure almost guarantees its status as an optional extra on a par with a keep-fit class.

I think that ER has to be justified on the grounds that it aids learning and I am attracted to the proposition that it helps to establish patterns in the brain and promote automaticity. Until there is research evidence to prove the case, I suggest that the strongest argument in support of ER is that it is the readiest means by which students can obtain the information about culture and history that they need for a deep level of communication. (88)

So, two brains? No of course not. But two different processes (as Phillips’ research seems to suggest). Acquisition vs learning anyone? That would certainly make us all think again. And IF there really ARE two different processes going on, then is that ‘learning mode’ actually better for us when we read and/or study? Better than, say absorbing language for and through pleasure? That perhaps is the question Scott Thornbury was asking some years ago in a talk called ‘No pain, no gain’, a threnody that has been picked up in a somewhat ramshackle way (it seems to me) by Jim Scrivener and Adrian Underhill. In passing I think they may be mixing cause and effect, and I wish there was more reading/research behind their claims, but still…..

Mention of Scott Thornbury reminds me that in the same edition of the ELT Journal he reviewed my book Essential Teacher Knowledge. I am (genuinely) flattered that the book was even worthy of his attention and he has a lot to say with which I readily agree (and wince about!). But in the course of his review (Thornbury 2013) he writes:

He (= me!) devotes the bulk of his overview to reviewing a theory (specifically Krashen’s Input Hypothesis) that, however influential it was in its time now feels somewhat superannuated. (131)

Well yes. And no. Because the discussion about the different processes of the brain, and the way that different activities stimulate different parts of it – something that Stephen Krashen talked about and which, though he may have got it wrong in many people’s eyes, still seems to me to be an ongoing and engaging issue – is brought into sharp focus yet again (in at least one part of my brain) by what I saw and heard last week.

Superannuated? Probably. I am, anyway, even if the arguments aren’t!!

What do you think?

References

Hill, D R (2013) Survey review: Graded readers. ELT Journal 67/1

Thornbury, S (2013) Review of Essential Teacher Knowledge. ELT Journal 67/1

Jeremy Harmer's Blog

- Jeremy Harmer's profile

- 180 followers