Teachers Write 7/15/13 Mini-Lesson Monday with Linda Urban

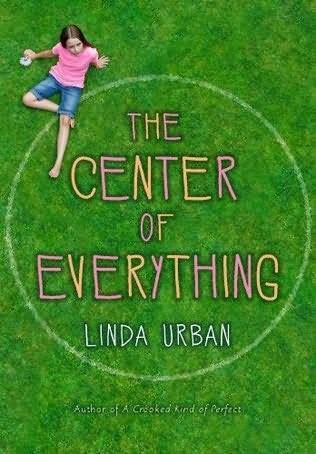

Happy Monday, everyone! Our guest author for today’s mini-lesson is the inimitable Linda Urban, whose new book THE CENTER OF EVERYTHING made me laugh and cry both. And on top of that, it made me crave donuts, too. You can read my not-quite-a-review of the book over at the Nerdy Book Club, but for now, Linda’s visiting us to talk about something that’s a part of all of our writing lives — time.

Happy Monday, everyone! Our guest author for today’s mini-lesson is the inimitable Linda Urban, whose new book THE CENTER OF EVERYTHING made me laugh and cry both. And on top of that, it made me crave donuts, too. You can read my not-quite-a-review of the book over at the Nerdy Book Club, but for now, Linda’s visiting us to talk about something that’s a part of all of our writing lives — time.

Got minute? Let’s talk time.

One of the coolest things about writing is that we can become masters of time. We can speed it up, summarizing entire weeks of a school year in a sentence (By the time my daily writing journal was full, I had come to the conclusion that Dana and I would never see eye to eye on this.) or slow time down so that a second-long gesture takes on weight and importance through its extention. (Dana stared at me, her pencil tapping out a funeral march, and I swear I could see the whole history of our friendship erased in the slow, steady shake of her head.). We use scenes to allow our readers to participate in the important stuff, to feel crucial emotions, to process information along with our characters, to experience action. We use summary to say: here’s a bit of info you’ll need to know, but you don’t have to fully engage in.

Time is one of the ways that we signal importance. We usually spend more time with major characters than minor ones. More time in scenes that detail key actions or emotions than in scenes with little consequence. You can use this assumption to your advantage. Want to hide a clue? How about sneaking it into a scene where the majority of our attention is spent on something else? Want readers to understand that a moment in a character’s past shapes their current actions? Don’t just tell us, take the time to show us in a scene.

And what about those really important parts of our story – the ones that mark crucial decisions or key turning points? We can use time to help those moments stand out in the mind of the reader.

Here’s an example from my most recent novel The Center of Everything, which has time (our perception of it and our desire to manipulate it) as one of its themes. In this scene, our main character, Ruby, who has been shielding herself from her emotions after the death of her grandmother Gigi, has just seen the color wheel project of her classmate, Nero DeNiro. The wheel is creative and funny and Ruby laughs a real, genuine laugh and feels for the first time in a long time. This is what happens next:

But when she stops laughing, all the little Nero faces start to blur. And Ruby has a bunch of thoughts.

One of them is that there is something wrong with her eyes.

Another is that there is something wrong with her ears, because when Lucy says “Are you okay?” it sounds like she’s using a speaker phone.

And another is that maybe there is something wrong with her hands, because they have dropped her pencil to the floor, and even though it makes sense for her to bend over and pick the pencil up, her hands are not moving. They are just sitting there on her color wheel, covering up all the complement lines. And there are drops of water landing on her hands and on the painted squares of color too, and the red and the orange are mixing all up into some other color that Ruby doesn’t have a name for and for which there is no complement on her color wheel, and she knows she is going to get a bad grade now.

“Ruby?” That’s Mrs. Tomas talking. “Ruby? Did you hurt yourself?”

What I hoped to do in this bit of the scene was to both slow time down in terms of the way that Ruby is processing and experiencing information, but also speed up the events around her. I spent time in the scene to put in the details that show how Ruby is experiencing sound, color and movement, so that the reader can truly feel her struggling to make sense of what is happening. I cut out the details that she doesn’t process, such as Lucy and Nero calling their teacher Mrs. Tomas over to the table to help. In playing with time in this way, I hoped to signal that this moment was unlike the ones that had come before – that it was important to Ruby and important to the story.

So, how might this work in the story that you are writing? Have you come to a crucial scene yet? Is there a key moment you want your readers to slow down and really experience? Think about that moment and see if you can find one central action in it – the turning of a door handle, the connection of bat to ball, the touch of a fingertip to the nape of a neck – and slow it down. Slow it way down.

As an experiment, let’s overdo. Let’s see exactly how long we can extend this moment. Keep it moving forward but detail every sense, every thought, every tiny change along the way. See how long you can make this moment last.

Not in the middle of a project? You can still give this a whirl. Take a fairy or folk tale you know well, identify a key moment, and extend that. Can you make the bite of a poisoned apple last for a paragraph? Two? A page?

When you’re done writing, take a look at what you’ve got. Chances are what you’ve written is way longer and more detailed than anything you’d want to put into a novel or short story. But I’m betting you’re going to find some great details in there, some emotions you hadn’t examined before, and some key words or phrases that you’ll want to keep in the scene – and maybe use again in times when you want your readers to remember that crucial plot moment.

If you did do the experiment using a moment from your work-in-progress, put it aside for a day or two and then see if you can edit it down to something that works for you. At the very least, I’m betting that this exercise has you thinking about that moment in a more vivid and dramatic way.

Note from Kate: Feel free to share a few lines of today’s writing in the comments if you’d like! Thanks again, Linda, for joining us! And don’t forget, everyone, that Jo has your Monday Morning Warm-Up today, too!

.