SCIENCE FICTION IN WORLD LITERATURE: FROM LUCIAN AND IBN AL-NAFIS TO HEINLEIN, ASIMOV, ARTHUR C. CLARKE, URSULA K. LE GUIN AND BEYOND———FROM THE WORLD LITERATURE FORUM SUGGESTED CLASSICS AND MASTERPIECES SERIES, ROBERT SHEPPARD, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

SCIENCE FICTION IN WORLD LITERATURE: FROM LUCIAN AND IBN AL-NAFIS TO HEINLEIN, ASIMOV, ARTHUR C. CLARKE, URSULA K. LE GUIN AND BEYOND———FROM THE WORLD LITERATURE FORUM SUGGESTED CLASSICS AND MASTERPIECES SERIES, ROBERT SHEPPARD, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

WORLD LITERATURE FORUM

Robert Sheppard, Editor-in-Chief, World Literature Forum

SCIENCE FICTION IN WORLD LITERATURE: FROM LUCIAN AND IBN AL-NAFIS TO HEINLEIN, ASIMOV, ARTHUR C. CLARKE, URSULA K. LE GUIN AND BEYOND

H.G.Wells’ War of the Worlds—World Classic of Science Fiction

What is “Science Fiction?” By its terms science fiction is the conjunction of “science” and “fiction,” which is to say the world of what we hold to be the most confirmable “reality” of our lives, or “what really is,” in fruitful union with the richest realm of the imagination, our deepest dreams of that alternative reality of “what could be,” or what might most delight us or be desired to be, or that which is most feared to be. It is also not incidentally, as is all art and literature, among our deepest conjectures of who we are and who we may dream ourselves to be, or to become.

According to science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein a handy short definition of almost all science fiction might read: “realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method.” Rod Serling’s definition is “fantasy is the impossible made probable. Science fiction is the improbable made possible.” Lester del Rey wrote, “Even the devoted aficionado—or fan—has a hard time trying to explain what science fiction is,” and that the reason for there not being a “full satisfactory definition” is that “there are no easily delineated limits to science fiction.”

Science fiction is largely based on writing rationally about alternative possible worlds or futures. It is similar to, but differs from pure fantasy in that, within the context of the story, its imaginary elements are largely possible within scientifically established or scientifically postulated physical laws of nature (though some elements in a story might still be pure imaginative speculation).

The settings for science fiction are often contrary to those of consensus reality but most science fiction still relies on a considerable degree of suspension of disbelief, which is facilitated in the reader’s mind by potential scientific explanations or solutions to various fictional elements. Science fiction elements include:

A time setting in the future in alternative timelines or in a historical past that contradicts known facts of history or the archeological record;

A spatial setting or scenes in outer space (e.g. spaceflight), on other worlds, or subterranean earth;

Characters that include aliens, mutants, androids or humanoid robots and other types of characters arising from a future human evolution;

Futuristic or plausible technology such as ray guns, teleportation machines, and humanoid computers;

Scientific principles that are new or that contradict accepted physical laws, for example time travel, wormholes or faster-than-light travel or communication (known to be possible but not yet feasible).

New and different political or social systems, e.g. dystopian, post-scarcity or post-apocalyptic; Paranormal abilities such as mind control, telepathy, telekinesis and teleportation;

Other universes or dimensions and travel between them.

Exploring the consequences of scientific innovations is one purpose of science fiction, as is making it a “literature of ideas.” Further, Science Fiction has evolved to be used by authors as a device to discuss philosophical questions of identity, the nature of humanity and the human condition, morality, desire and social structure.

THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE FICTION: WHO WAS THE “FIRST SCIENCE FICTION WRITER” IN WORLD LITERATURE?

Of course, the identification of the first science fiction writer in history is dependent upon our definition of what is science fiction. That in turn will depend on our definitions of what is science and what is fiction. These terms are not constant but vary and shift with historical, intellectual and cultural circumstance. Nonetheless, looking back on all known past literature it is possible to identify writers in the past who approached most nearly the modern themes, subject matter and imaginative intent of the institution we now regard as the modern genre of “Science Fiction.” Various national or individual claimants to the title of the “the first work of science fiction” are proposed from time to time, from the True History of 2nd Century Roman writer Lucian to some of the tales of the 1001 Arabian Nights, to the 10th Century Japanese “Tale of the Bamboo Cutter” to the Robinson Crusoesque desert island tale Theologus Autodidacticus (The Self-Taught Theologist) by 13th Century Arabic writer Ibn al-Nafis. In my judgment, the Roman writer Lucian has the strongest claim to the title of “the father of science fiction.”

Lucian–2nd Century AD Roman Writer—-The First Science Fiction Writer in World Literature

LUCIAN’S “TRUE HISTORY” AS SCIENCE FICTION

As most of us are not familiar with Lucian and his True History or Ibn al-Nafis’ Theologus Autodidacticus I shall take a bit more time and space to outline their contents compared to other modern works presented below with which the reader is presumed to be more knowledgeable.

In his Roman 2nd Century AD classic, True History, Lucian as narrator joins a company of adventuring heroes similar to “Jason and the Argonauts” sailing westward through the “Pillars of Hercules” (the Strait of Gibraltar) in order to explore lands and inhabitants beyond the Ocean. They are blown off course by a strong wind, and after 79 days come to an island. This island is home to a river of wine filled with fish, and bears a marker indicating that Hercules and Dionysius have traveled to this point, alongside normal footprints and giant footprints.

Shortly after leaving the island, they are lifted up by a tornado-like whirlwind and after seven days aloft are deposited on the Moon. There they find themselves embroiled in a full-scale war between the king of the Moon and the king of the Sun over colonization of the Morning Star, involving armies including such exotica as stalk-and-mushroom men, acorn-dogs (“dog-faced men fighting on winged acorns”), and cloud-centaurs. Unusually, the Sun, Moon, stars and planets are portrayed as locales, each with its unique geographic details and inhabitants. The war is finally won by the King of the Sun’s armies clouding the Moon over. Details of the Moon follow: there are no women, and children grow inside the calves of men prior to birth.

After returning to Earth, the adventurers become trapped in a giant 200 mile-long whale where live many groups of people whom they rout in war. They also reach a sea of milk, an island of cheese and “The Isle of the Blessed,” a species of afterworld. There Lucian meets the heroes of the Trojan War from the Iliad, other mythical men and animals, and even Homer himself. They find the historian Herodotus being eternally punished for the “lies” he published in his “Histories.”

After leaving the Island of the Blessed, they deliver a letter to Calypso given to them by Odysseus explaining that he wishes he had stayed with her so he could have lived eternally. They then discover a chasm in the Ocean, but eventually sail around it, discover a far-off continent, prophetic of Columbus’ discovery of America, and decide to explore it. The book ends rather abruptly with Lucian saying that their adventure there will be the subject of following books.

Lucian’s True History eludes a clear-cut literary classification or genre. Its multilayered character has given rise to interpretations as diverse as science fiction, fantasy, satire or parody of such classics as the Odyssey, depending on how much importance scholars attach to Lucian’s explicit intention of telling a story of candid falsehoods. Nevertheless, I feel on the whole that True History may properly be regarded effectively as science fiction because Lucian often achieves that sense of “cognitive estrangement” which Darko Suvin has defined as the generic distinction of Science Fiction, that is, the depiction of an alternate world, radically unlike our own, but relatable to it in terms of continuity of the laws and limits of action. Thus, part of the tale that qualifies it as science fiction, rather than as fantasy or imaginative fiction, involves Lucian and his seamen living out an epic battle for territorial and colonization rights that preserves a field of action, including reality and science-based laws and limitations alongside human and social motivations, continuous of our own world’s realities.

In sum, characteristic of science fiction themes and topoi, Lucian’s True History depicts:

travel to outer space

encounter with alien life-forms, including the experience of a first encounter event

interplanetary war and imperialism

colonization of planets

artificial atmosphere

liquid air

reflecting telescopes

motif of giganticism

creatures as products of human technology (robot theme)

worlds working by a set of alternate ‘physical’ laws

explicit desire of the protagonist for exploration and adventure

Ibn al-Nafis—13th Century Arabic Writer—The First Islamic Science Fiction Writer in World Literature

IBN AL-NAFIS’ THEOLOGUS AUTODIDACTICUS (The Self-Taught Theologue)

Ibn al-Nafis’ 13th Century classic Theologus Autodidacticus and its progenitors were part of “The Islamic Golden Age” that is often overlooked in its contributions to both modern science and science fiction. From the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad the Arab world took greater care than the Christian West to preserve and build upon the rationalist heritage of the Greek and Roman classical heritage through the works of such renown scholars as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Ibn Rushd (Averroes), Al-Ghazali, Moses Maimonides and others, who in turn at a later time contributed to the rediscovery of the rationalist Greco-Roman classical tradition through their influence on medieval scholars such as the neo-Aristotelian St. Thomas Aquinas and their successors embodied in the Western Renaissance.

The Theologus Autodidacticus was less a work of imaginative science fiction than a continuation of a philosophical thought experiment deriving from the prior Islamic Golden Age works The Incoherence of the Philosophers by Ibn Sina and its more immediate precursor work by Ibn Tufail (Abubacer), the Philosophus Autodidacticus (Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān “Alive, Son of Awake” or “The Self-Taught Philosopher: The Improvement of Human Reason: Exhibited in the Life of Hai Ebn Yokdhan.” These philosophical works sought to explore the relationship of human reason, scientific proof based on individual observation of the world and religious revelation through the thought experiment of placing a feral child on a desert island without human language, society, education or guidance and speculating as to what naked observation of the world and reason would produce in human understanding. Ibn Tufail, like St. Thomas Aquinas seeking to reconcile reason and the creator-God of a rational universe, speculated that the island boy armed only with scientific observation and reason would arrive at the same rational understanding as the most learned philosophers armed with the Islamic and Greco-Roman tradition. Ibn al-Nafis, who was not original but rather copied Ibn Tufail’s desert island feral child motif, sought to take exception with Ibn Tufail and invoke more a process of independent religious revelation which would lead to independent discovery and affirmation of Islam by the feral child, supplementing the role of naked reason and scientific observation. Nonetheless he affirmed that all was reconcilable and harmonious. Both desert island works had far-reaching effects through translation in the West, and Daniel Defoe was known to have read a translation prior to composing Robinson Crusoe, and such speculations informed the reasoning of Enlightenment figures such as Voltaire and the voyage of discovery in Candide, the Cartesian Method of Descartes, and the tabula rasa of Locke, precursors of the rise of science.

Theologus Autodidacticus thus presents less of a voyage of discovery into an alternative universe than an account of a feral boy’s development on a desert island and his self-education, followed by his discovery and return to civilization by sailors and the attempt to reconcile autonomously-derived understanding with traditional and civilization-derived understanding. The last two chapters of the Theologus Autodidacticus, however, exhibit some characteristics of science fiction as they relate how the feral boy, Kamil, has independently arrived at the Biblical and Koranic prediction of Revelations and the Koran of the Apocalypse, “end of the world” and “Last Judgment” involving the resurrection of the bodies of the dead. He derives this prophetic knowledge scientifically through the study of astronomy, in which he observes a process of the slow destruction of the earth’s ecliptic, or slant relative to the sun from which the seasons arise. Thus in the modern science fiction tradition Ibn al-Nafis in the 13th Century predicts a Climate Change Apocalypse where the slant of the ecliptic will be lost, leading to a destruction of the seasons, the overheating of the equator and freezing of the poles and a consequent forced migration of peoples from now intolerable climates resulting in clashes and a World War of Armageddon which extirpates the human race from the planet. All is not lost however, as the re-tilting of the planet relative to the sun will eventually tilt over in the opposite direction, restoring the seasons, and the benign return of Climate Change will result in a resurrection of the dead bodies and a new cycle of resurgent life.

The other contenders for the title of the first work of science fiction are clearly much weaker. The 1001 Nights Arabian Entertainment, though incorporating some sci-fi motifs is clearly of the fantasy rather than sci-fi genre, with the laws of science not restraining the free play of fantasy and negating the comparability of the fantastic realm with the world of our lived-in reality. The Japanese 10th Century “Tale of the Bamboo Cutter” (Taketori Monogatari) presents a fantasy of a “Tom Thumb” sized princess, Princess Kayuga, discovered and born from a bamboo stalk by a cutter who proves to be a princess of the Moon People. The tale tells of how she grows up on earth in the family of the bamboo cutter and is courted by all the earthly princes and proposed to by the Emperor of Japan. She rejects all these suitors, however, until an embassy from the Moon comes to return her to her lunar home, evocative also of the Chinese tale of Chang’E. Though incorporating the motif of interplanetary travel and civilizations, there is little of science or continuity of the laws of nature as a restraint on pure fantasy and impossibility. Thus, on the whole, the title of “The Father of Science Fiction” and “The First Work of Science Fiction” in history and World Literature is best conferred on Lucian and his “True History.”

Gulliver’s Travels–Proto-Science Fiction

PROTO-SCIENCE FICTION FROM THE ENLIGHTENMENT TO THE ROMANTIC AGE

Arising from the Age of Reason and the development of modern science itself, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels was one of the first true science fantasy works, together with Voltaire’s Micromegas (1752) and Johannes Kepler’s Somnium (1620). Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan have termed the latter work the first science fiction story. It depicts a journey to the Moon and how the Earth’s motion is seen from there. The Blazing World written in 1666 by English noblewoman Margaret Cavendish has also been described as an early forerunner of science fiction. Another example is Ludvig Holberg’s novel Nicolai Klimii iter subterraneum, 1741. Some have argued that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) was the first work of science fiction.

Following the 18th-century development of the as a novel itself literary form, in the early 19th century, Mary Shelley’s books Frankenstein and The Last Man helped evolve the form of the science fiction novel; later Edgar Allen Poe wrote a story about a flight to the moon. More examples appeared throughout the 19th century as the scientific age took on greater momentum and began to uproot and reform everyday life to a greater and greater extent.

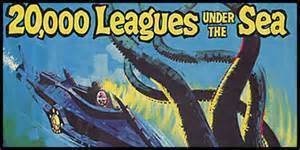

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN SCIENCE FICTION—-THE TWO FOUNDING TITANS: JULES VERNE & H.G. WELLS

Jules Verne–Father of Modern Science Fiction

Most of us grow up with the great classics of Science Fiction, either in books or rendered in movies, with place of honor held by the works of the two great authors of the first age of Science Fiction: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty-Days, Journey to the Center of the Earth, The War of the Worlds, The Time Machine and many others. They have now risen to become part of the canon of World Literature, creating a body of work that became popular across broad cross-sections of society, well beyond the smaller sub-culture of sci-fi enthusiasts. They arose out of the enthusiasms and anxieties of the Industrial Revolution and Scientific Revolution as technologies such as the telegraph, steam engine, railroads, steamships, the automobile, the tank, submarine and machine-gun, airplane and electric lighting and power were completely reshaping the human landscape of the modern world. They also confronted the dilemmas and challenges that such scientific developments as Darwin’s Theory of Evolution and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity posed for the understanding of the human condition and its traditional institutions such as religion, the nation-state and the family.

H.G. Wells

Wells’ The War of the Worlds for example (1898) describes an invasion of late Victorian England by Martians using tripod fighting machines equipped with advanced weaponry. It is a seminal depiction of an alien invasion of Earth, and in presenting a collision with a species more advanced than humanity is a profound shock to our geo-centric and ego-centric pretensions of human superiority and privileged uniqueness. Wells in that work also developed the narrative technique of telling the story by an average person as narrator unexpectedly caught up in a technological cataclysm, allowing a focus not simply on astounding technology, but on the human and psychological dimensions of technological upheaval. This focus would be echoed in the later development of the genre from “Hard Science Fiction” to the sub-genres of “Social Science Fiction” and “Soft Science Fiction” epitomized by such later writers as Phillip K. Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin.

Verne also created iconic characters of great psychological depth such as Captain Nemo and questioned such human institutions as the nation-state, as memorable as the technological speculations concerning undersea submarine travel, space ships on interplanetary journeys, time machines and laser weapons. With such great authors the advance of technology elicited not only admiration and awe, but also concern for the ambivalent meaning and potential of such innovations for morality, the exercise of power, society and the human condition.

Jules Verne’s Science Fiction Classic 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

1920’s-1930’s—-EARLY VISIONARIES OLAF STAPLEDON & KAREL CAPEK: LAST AND FIRST MAN, STAR MAKER, THE WAR OF THE NEWTS & ROBOTS

Olaf Stapledon—Cosmic Visionary

OLAF STAPLEDON

Olaf Stapledon, an accomplished Oxford scholar, was a writer of extraordinary depth and breadth of vision who deeply influenced later icons of Science Fiction such as Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke as well as such writers as Borges, H.P. Lovecraft, Priestly, Bertrand Russell and Virginia Woolf. Once again, I shall devote a bit more time and space to Stapledon as he is less familiar to our readers than the better known masters.

Stapledon was a scholar in history at Oxford prior to the First World War and was deeply influenced by Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. During WWI he was a conscientious objector and served in the ambulance service at the front in Belgium and France in lieu of military service. After the war he completed a Ph.D in Philosophy, but the success of his science fiction writing enabled him to give up academia to become a full-time writer instead. His first major success was with the publication of Last and First Men, a work of immense vision and unprecedented scale in the genre, describing the history of humanity from the present onwards across two billion years and eighteen distinct human species, of which our own is the first. Stapledon’s conception of history is based on both Darwin and the Hegelian Dialectic, following a repetitive cycle with many varied civilizations rise from and descending back into savagery over millions of years. In this he was also influenced by the historical theories of Oswald Spengler and Vico, following the rise and fall of civilizations as organic but historically determined entities destined to birth, a limited lifespan and inevitable decline and destruction, which is, however, followed by civilizational rebirth. But this process is also one of a general upward spiraling progress, as the later civilizations rise to far greater heights than the first and earlier ones. The book anticipates the science of genetic engineering, interplanetary colonization and migration, interplanetary and inter-species war, conflict between creator and created species, an altered sexuality with evolution of multiple sexes beyond the male and female, and among the later evolutionary reincarnations of humanity is an early example of the fictional supermind: a super-consciousness composed of many telepathically-linked individuals. Humanity ends with the occurrence of a supernova which destroys the solar system, but not before the final race devises seed-viruses which are capable of surviving journeys to other solar systems and the seeding of life there in the tradition of interstellar “panspermia” in the hope of a newer evolution of life on the planets of distant stars. The course of evolution from the present human species (the First Men) onwards to the final reported species, the Eighteenth Men:

First Men. (Chapters 1–6) Our own species: the rivalry of America and China, leads to formation of the First World State followed by its destruction as a result of using up all natural resources, followed by the Patagonia Civilization 100,000 years hence, with its cult of Youth, and its destruction after the sabotage of a mine which leads to a colossal subterranean atomic explosion and an ensuing intercontinental nuclear holocaust, rendering most of the Earth’s surface uninhabitable for millions of years save for the poles and the northern coast of Siberia. The only survivors are thirty-five humans stationed at the North Pole who eventually split up into two separate species, the Second Men and some sub-humans.

Second Men. (Chapters 7– 9) “Their heads, indeed, were large even for their bodies, and their necks massive. Their hands were huge, but finely moulded…their legs were stouter…their feet had lost their separate toes…blonde hirsuite appearance…Their eyes were large, and often jade green, their features firm as carved granite, yet mobile and lucent. …not till they were fifty did they reach maturity. At about 190 their powers began to fail…” Unlike our species, egotism is virtually unknown to them. At the acme of their highly advanced civilization, a protracted war with the Martians finally ends with the Martians extinct and the Second Men gone into eclipse.

Third Men. (Chapter 10) “Scarcely more than half the stature of their predecessors, these beings were proportionally slight and lithe. Their skin was of a sunny brown, covered with a luminous halo of red-gold hairs… golden eyes… faces were compact as a cat’s muzzle, their lips full, but subtle at the corners. Their ears, objects of personal pride and of sexual admiration, were extremely variable both in individuals and in races. … But the most distinctive feature of the Third Men was their great lean hands, on which were six versatile fingers, six antennae of living steel.” They are deeply interested in music and in the genetically engineered design of living organisms.

Fourth Men. (Chapter 11) Giant brains, built by the Third Men. For a long time they help govern their creators, but eventually come into conflict. After reducing the Third Men to the status of lab animals, they eventually reach the limits of their scientific abilities.

Fifth Men. (Chapters 11–12) An artificial human species designed by the preceding brains: “On the average they were more than twice as tall as the First Men, and much taller than the Second Men… the delicate sixth finger had been induced to divide its tip into two Lilliputian fingers and a corresponding thumb. The contours of the limbs were sharply visible, for the body bore no hair, save for a close, thick skull-cap which, in the original stock, was of ruddy brown. The well-marked eyebrows, when drawn down, shaded the sensitive eyes from the sun.” After clashing with and finally eliminating the Fourth Men, they develop a technology greater than Earth had ever known before. When Earth ceases to be habitable, they terraform Venus, committing genocide on its marine native race which tries to resist them – but do not cope well after the move.

Sixth Men. (Chapter 13) “Sadly reduced in stature and in brain, these abject beings… gained a precarious livelihood by grubbing roots upon the forest-clad islands, trapping the innumerable birds, and catching fish… Not infrequently they devoured, or were devoured by, their seal-like relatives.” After tectonic changes provide them with a promising land mass, they fluctuate like the First Men and repeat all their mistakes.

Seventh Men. Flying humans, “scarcely heavier than the largest of terrestrial flying birds”, are created by the Sixth Men. After 100 million years, a flightless pedestrian subspecies appears which re-develops technology.

Eighth Men. “These long-headed and substantial folk were designed to be strictly pedestrian, physically and mentally.” When Venus becomes uninhabitable, about to be destroyed along with the entire inner solar system, they design the Ninth Men, who will live on Neptune.

Ninth Men. (Chapter 14) “Inevitably it was a dwarf type, limited in size by the necessity of resisting an excessive gravitation… too delicately organized to withstand the ferocity of natural forces on Neptune… civilization crumbled into savagery.” From there, savagery sinks further into brutedom.

Tenth to Seventeenth Men. “Nowhere did the typical human form survive.” Sentience re-emerges from animals on multiple occasions. The Fifteenth and Sixteenth achieve a great civilization and learn to study past minds. (These species are essentially Neptunian versions of the Second and Fifth Men, respectively.) It is not until the Sixteenth Men, the first of the Neptunian artificial species, that the cycle of rise and collapse of civilization is finally ended, and steady progress takes its place. The Sixteenth Men, frustrated by their inability to improve their civilization, decide that their nature is insufficiently advanced to produce a truly perfect community, and create an artificial species, the Seventeenth Men, to succeed them; however, the Seventeenth Men are “flawed” in some unspecified way, unimagined by the 16th due to their lesser awareness, and last only a short period of time before being replaced by the Eighteenth Men, essentially a more perfect version of their own species.

Eighteenth Men. (Chapters 15–16) The most advanced humans of all. A race of philosophers and artists with a very liberal sexual morality. “Superficially we seem to be not one species but many.” (One interesting aspect of the Eighteenth Men is that they have a number of different “sub-genders,” variants on the basic male and female pattern, with distinctive temperaments. The Eighteenth Men’s equivalent of the family unit includes one of each of these sub-genders and is the basis of their society. The units have the ability to act as a group mind, which eventually leads to the establishment of a single group mind uniting the entire species.). This species no longer died naturally, but only by accident, suicide or being killed. Despite their hyper-advanced civilization, they practice ritual cannibalism. They are eventually extinguished on Neptune after a supernova infects the sun, causing it to grow so hot that it consumes the remains of the solar system, faster than any means of escape they can devise. Unable to escape, this last species of man devises a virus to spread life to other worlds and cause the evolution of new sentient species throughout the galaxy.

But the process of evolution can also be downward as well as upward. Stapledon on numerous occasions posits the emergence of “subhuman” human successors who descend towards a lower animality:

Baboon-like Submen. (Chapter 7) “Bent so that as often as not they used their arms as aids to locomotion, flat-headed and curiously long-snouted, these creatures were by now more baboon-like than human”.

Aquatic Seal-like Submen. (Chapter 13) “The whole body was moulded to stream-lines. The lung capacity was greatly developed. The spine had elongated, and increased in flexibility. The legs were shrunken, grown together, and flattened into a horizontal rudder. The arms also were diminutive and fin-like, though they still retained the manipulative forefinger and thumb. The head had shrunk into the body and looked forward in the direction of swimming. Strong carnivorous teeth, emphatic gregariousness, and a new, almost human, cunning in the chase, combined to make these seal-men lords of the ocean”. In this they parallel the actual strange but true history of evolution of the seal, whale and porpoise from an air-breathing land animal thought to resemble the dog into an aquatic species on Earth.

Period of Eclipse. (Chapter 14) “Man’s consciousness was narrowed and coarsened into brute-consciousness. By good luck the brute precariously survived.” Nature succeeds in colonizing Neptune where sentient life fails. Human-derived mammals of all shapes come to dominate Neptune’s ecosystem before adapting well enough for the vestiges of opposable thumbs and intelligence to become assets again.

Olaf Stapldon’s Star Maker–The Ultimate Cosmological Vision

As if a two-billion year vision of the future of the human species were not enough, Stapledon follows his prophetic masterpiece with an even greater cosmological speculation in Star Maker, transcending the “Big Bang” with a vision of the creation of alternative universes by a Supreme Artist-Quasi-God-Universe Maker, termed the “Star Maker.”

The climax of the book is the “supreme moment of the cosmos”, when the cosmical mind (which includes the psychically-voyaging narrator) attains momentary contact with the “Star Maker” of the title. The Star Maker is the creator of the universe, but stands in the same relation to it as an artist to his work, and calmly assesses its quality without any feeling for the suffering of its inhabitants. This element makes the novel one of Stapledon’s efforts to write “an essay in myth making”.

After meeting the Star Maker, the traveler is given a “fantastic myth or dream,” in which he observes the Star Maker at work. He discovers that his own cosmos is only one of a vast number, and by no means the most significant. He sees the Star Maker’s early work, and learns that the Star Maker was surprised and intensely interested when some of his early “toy” universes — for example a universe composed entirely of music with no spatial dimensions — displayed “modes of behavior that were not in accord with the canon which he had ordained for them.” He sees the Star Maker experimenting with more elaborate universes, which include among others the traveler’s own universe, and a triune universe which closely resembles “Christian orthodoxy” (the three universes respectively being hell, heaven, and reality with presence of a savior). The Star Maker goes on to create “mature” universes of extraordinary complexity, culminating in an “ultimate cosmos,” through which the Star Maker fulfills his own eternal destiny as “the ground and crown of all things.” Finally, the traveler-narrator returns to Earth at the place and time he left, to resume his life there.

[image error]

KAREL ČAPEK—Czech Inventor of the word “Robot”

KAREL ČAPEK

Stapledon’s Czech contemporary Karel Čapek is perhaps best known for his coinage of the word “robot” in his early play “R.U.R.—Rostum’s Universal Robots,” which describes the creation of an “android” species of robots endowed with human-like intelligence and consciousness. Many of his works discuss ethical aspects of industrial inventions and processes already anticipated in the first half of the 20th century. These include mass production, nuclear weapons, and post-human intelligent beings such as robots or salamanders (newts). Čapek also expressed fear from social disasters, dictatorship, violence, human stupidity, the unlimited power of corporations, and greed. Capek tried to find hope, and the way out. Čapek’s literary heirs include Ray Bradbury, Salman Rushdie, Brian Aldiss, and Dan Simmons. From the 1930s onward, Čapek’s work became increasingly anti-fascist, anti-militarist, and critical of what he saw as “irrationalism.”

The War With the Newts

Čapek’s most mature work was War with the Newts (Válka s mloky) sometimes also translated as War with the Salamanders. The 1936 satirical science fiction novel concerns the discovery in the Pacific of a sea-dwelling race, an intelligent breed of newts, who are initially enslaved and exploited by their human masters and owned by profit-seeking corporations. They acquire human knowledge and intelligence, however, and rebel leading to a global war for supremacy between the two intelligent species on earth. Ultimately the Newts triumph due to human mendacity. There are obvious similarities to Čapek’s earlier R.U.R. which also included conflict between humans and their created “android” species of robots, but also some original themes and the fuller development as a full novel.

THE RISE OF GOLDEN AGE OF SCIENCE FICTION IN THE LATE 20TH CENTURY—THE “BIG THREE” MODERN GIANTS: HEINLEIN, ARTHUR C. CLARKE & ISAAC ASIMOV

In the early 20th century, pulp magazines helped develop a new generation of mainly American science fiction writers, influenced by Hugo Gernsback, the founder of Amazing Stories magazine, after whom the “Hugo” science fiction award for excellence is named. In 1912 Edgar Rice Burroughs published A Princess of Mars, the first of his three-decade-long series of Barsoom novels, situated on Mars and featuring John Carter as the hero. The 1928 publication of Philip Nolan’s original Buck Rogers story, Armageddon 2419, in Amazing Stories was a landmark event. This story led to comic strips featuring Buck Rogers (1929), Brick Bradford (1933), and Flash Gordon (1934). The comic strips and derivative movie serials greatly popularized science fiction.

In the late 1930s, John W. Campbell became editor of Astounding Science Fiction magazine and a critical mass of new writers emerged in New York City in a group called the Futurians, including Isaac Asimov, Damon Knight, Donald Wollheim, Frederik Pohl, James Blish, Judith Marril, and others. Other important writers during this period included E.E. (Doc) Smith, Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and A.E. Vogt. Working outside the Campbell influence were Ray Bradbury and Stanislaw Lem. Campbell’s tenure at Astounding is considered to be the beginning of the Golden Age of Science Fiction, characterized by Hard Science Fiction stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress. This lasted until post-war technological advances, new magazines such as Galaxy, edited by H. L. Gold, and a new generation of writers began writing stories with less emphasis on the hard sciences and more on the social sciences.

All three of the giants of contemporary science fiction were members of the WWII Generation that had seen the genre evolve from its beginnings with the Victorian and Edwardian “scientific romances” of Verne and Wells and, supercharged by the acceleration of technological change, looked forward with prophetic vision and imaginative creativity.

All three of the giants of the Golden Age of Science Fiction were members of the WWII Generation that had seen the genre evolve from its beginnings with the Victorian and Edwardian “scientific romances” of Verne and Wells and, supercharged by the acceleration of technological change, looked forward with prophetic vision and imaginative creativity.

[image error]

Robert Sheppard's Literary Blog & World Literature Forum

The Blog also containss posts from the World Literature Forum, of which Ro This Blog contains the literary works, discussions, opinions and musings of Robert Sheppard, Author of Spiritus Mundi, novel.

The Blog also containss posts from the World Literature Forum, of which Robert Sheppard is the Editor-in-Chief, which is syndicated on Scoop.It!, LinkedIn and Facebook. You are invited to visit the author's Wordpress Blog and join the LinkedIn and Facebook World Literature Forum Groups as well:

http://robertalexandersheppard.wordpr...

http://www.linkedin.com/groups/World-...

http://www.linkedin.com/groups/World-...

https://www.facebook.com/pages/feed#!... ...more

- Robert Sheppard's profile

- 98 followers