¡Feliz Cumpleaños, José Martí!

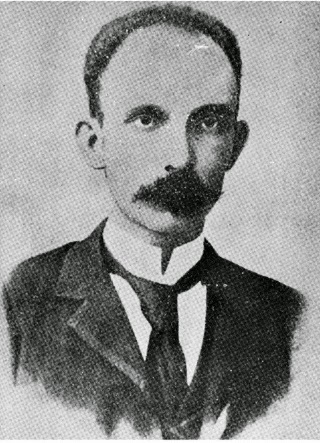

Poet. Journalist. Playwright. Exile. Revolutionary. Patriot. José Julian Martí is a founding father for Cubans and Cuban-Americans. Born on this day in 1853, Martí would come to lead the ideological charge against Spain in Cuba's War of Independence. He bore only his pen and his gifts for oration, and with those humble tools, Martí helped bring an independent nation into being. When he did finally enter the war physically, he didn't last long. Shot off his horse, Martí is said to have died facing the sun.

Poet. Journalist. Playwright. Exile. Revolutionary. Patriot. José Julian Martí is a founding father for Cubans and Cuban-Americans. Born on this day in 1853, Martí would come to lead the ideological charge against Spain in Cuba's War of Independence. He bore only his pen and his gifts for oration, and with those humble tools, Martí helped bring an independent nation into being. When he did finally enter the war physically, he didn't last long. Shot off his horse, Martí is said to have died facing the sun. As a child who attended a bilingual school in Miami run by Cuban exiles, I was taught that Martí was second only to Jesus and la Virgencita. We memorized his poetry ("Cultivo una rosa blanca" being my favorite), and knew his face the way other kids recognize Abraham Lincoln.

When I sat down to write a novel set during the Cuban War of Independence, I knew Martí had to figure in somehow. What I didn't expect is that he would wind up in the novel as a minor character. He's in it for only a few scenes, but they're some of my favorite in the book.

In honor of Martí's birthday, my most excellent publisher, Europa Editions, is holding a contest for a free galley of THE DISTANT MARVELS.

Click through to their facebook page for a chance to enter, then come back here where I've got an excerpt for you from the novel, one featuring Martí himself.

The excerpt starts with a female revolutionary, Lulu, the mother of the novel's protagonist, María Sirena. Lulu, her husband, and her daughter, have just reached a camp of rebels, and they want to join the fight. Read on (and don't forget to enter!).

“Señores,” she began. “Compatriotas. You hope to found a free nation here, do you not?” She spoke animatedly, her delicate hands dancing before her, as if she were doing a floréo in a flamenco dance. The men watched, mesmerized. Even Agustín stopped scowling, the grimace falling from his face at once. “A nation is made up of men, sí, and women, too. As well as children.” She pointed at me, and my face felt warm. I looked away, unable to bear so many of the insurgents’ eyes fixed on me at once. “Then, let us fight. Let us learn to defend this new nation. We Cuban women can be midwives to this great birth, if only you’ll let us.”

There was silence. I wanted to applaud, shout, “Bravo, Mamá!” I didn’t, of course. I sat in the saddle while the pregnant mare shuddered beneath me, huffing and snorting in that way of horses. The animal was the only thing making a sound. I ran my hands over her pelt to calm myself, and the horse settled down, too.

That was when I noticed the poet for the first time. He parted the group of men and approached us, a heavy pack still on his back, as if he expected to have to leave the modest campsite at any moment. “It’s a pleasure to meet a family so brave,” he said, extending a hand to my father, and then, kissing my mother on both cheeks, like a European.

Lulu looked away demurely, whispered, “Gracias,” and returned to the horse.

“Who is that?” I whispered to Lulu.

“That is the man who called the war,” she said breathlessly. Later, I’d learn all about José Julián Martí, the poet and patriot, who had inspired Cubans on the island and abroad to rise up over Spain. But in that moment, all I saw was a slender man, with a large forehead and a thin mustache that curled up at the ends. His eyes were small and brown. There was something of the rodent about his features, though I liked him at once. Lulu and Agustín were struck dumb by his presence. They had seen him give a speech once, in New York, but familiarity had done nothing to diminish Martí's aura in their eyes.

“You may camp with us tonight, and ride with us tomorrow if you’d like,” Martí said. My mother had charmed him, I knew. While my father had gripped his balls to show his strength, my mother had said a few words to the right man. I took note of the difference.

Another one of the insurgents, a bald man with a gleaming machete dangling from a rope around his waist, spoke up, “Oye, you have no military experience, poet. Perhaps it’s best if you--”

“Cállate,” said another insurgent to the bald man. “This is Martí you’re talking to.” Then, facing my father, Martí’s defender said, “Make yourselves at home.”

There was no more arguing against our presence that night.

Later, after we’d eaten a meal of roasted rabbit, my mother introduced me to Martí. "Señor," my mother said, holding me tight against her thighs, "mi hija, María Sirena." She presented me to the poet by caressing my cheek with her hand. I leaned into her touch, hungry for it still, though I was fourteen years old.

The poet cocked his head to the side. "I can tell already that you are your mother's muse," he said.

When Martí left us, my mother said, "Take a good look, María Sirena. There goes a man without equal."

"Papá?" I asked her, and she laughed.

"No, mi cielo, Martí. There would be no rebellion if not for the poet." Her gaze lingered long after the man, even after he’d lied down in his hammock, the only part of him visible a bony knee.

Published on January 28, 2015 08:58

No comments have been added yet.