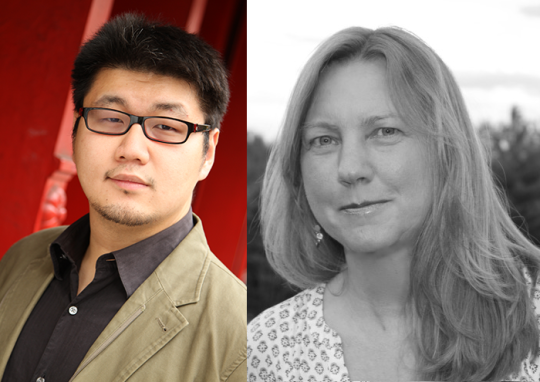

Conversations: Susan Karwoska Interviews Bill Cheng

“Blues is a kind of art form that is without boundaries; it doesn’t matter who you are, where you’re from—if you’re ready to receive it, it can change how you see.”

Bill Cheng is the author of Southern Cross the Dog (Ecco Press, 2013). His fiction has appeared and been collected in Guernica, The Book of Men, and Tales of Two Cities: The Best and Worst of Times in Today’s New York. He is the recipient of a 2015 Fellowship in Fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts and received his MFA from Hunter College.

Susan Karwoska (Fellow in Fiction, 2012 and Advisory Board member) conducted this interview with Bill by email in September 2015.

Susan Karwoska: First of all, congratulations on receiving a NYFA Fiction Fellowship this year. I served on the fiction panel and believe me, the competition was fierce. One of the unique things about this award is that it can be given to a young unpublished writer or to a well-known author—the writing is everything—but I have the sense that it means different things to writers at different stages of their careers. As someone who just published a debut novel to much acclaim, what does it mean to you to be selected as a NYFA Fellow?

Bill Cheng: I won’t lie—it feels good. It makes it easier to walk into a room with your peers and not feel like a total fraud all the time. I don’t know; I’m a weak animal. As much as I hate this part of me, I need someone to look at what I’m doing and say, “This is good.” It’s not healthy for a writer, or anyone really, to live for that kind of affirmation but it’s also hard to resist. Writing is so solitary. You can slip out of sync with the world if you’re not careful.

SK: The novelist Jane Smiley, writing in The Guardian, said that you made your debut novel, Southern Cross the Dog “out of fascination and research,” and many reviewers have commented on the fact that you are a Chinese-American born and raised in Queens writing about a young black man living in the Jim Crow-era Deep South, a place you did not visit until after you finished the novel. What was it that drew you to this particular time and place, and was it complicated to lay claim to a story so far removed from your own?

BC: The book came to me at a time when I was deep into blues music. I think blues is a kind of art form that is without boundaries; it doesn’t matter who you are, where you’re from—if you’re ready to receive it, it can change how you see. But the blues is also of a particular place, of a particular time, telling very particular stories. I wanted to write a book that honored that.

SK: The language in Southern Cross the Dog is lyrical and haunting, suffused with the mythology and melancholy of the blues. You dedicated the book to “all the late, great bluesmen” and claim a life-long passion for the form. What is it that draws you to the blues? And did this interest make it easier for you to develop the voice of the novel, or did it take you a while to find it?

BC: I was into the music before I wanted to write this book, so for years I’d been filling myself with this music every day. These voices. Their stories. I read a lot about the region, about different musicians. Keep in mind, I wasn’t thinking of it as preparation. I was just trying to enrich myself. For me, blues is a way to not only express grief and pain and sorrow, but also a means to be communal in that sorrow. To find joy and hope at the other side of it.