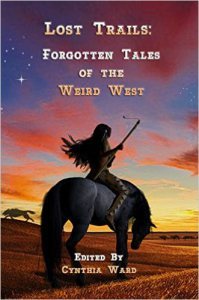

Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West – Vol 1

Editor Cynthia Ward kindly contributed the following words about her book Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West: Volume One

Editor Cynthia Ward kindly contributed the following words about her book Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West: Volume One

“It may sound nonsensical when I say Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West: Volume One, the anthology I edited for WolfSinger Publications, was born of the disconnect between the “Wild West” in nonfiction and the “Wild West” in fiction. After all, there’s always a disjunction between fact and fiction, even without the Weird factor. But the disjunction that moved me to editorship was the one between the mostly straight white cisgender worlds I was encountering in Weird West fiction, and the realities of everyday life not only in the modern West, but in the historical.

I live in the rural West and my neighbors within one or two doors are white, black, Hispanic, Asian, mixed race, young, old, Christian, atheist, neurotypical, neurodiverse, able-bodied, and differently abled. I study the historical West and encounter black cowboys, gay cowboys, transgender Zuni, Chinese prospectors, Native and mestizo vaqueros, African-American sheriffs and marshals, Muslim cavalry scouts, buffalo soldiers, male prostitutes, rodeo horsewomen, cross-dressing stagecoach drivers and jazz musicians, Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, Sephardic Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition, and even more diversity and intersectionality.

Yet, when I was reading Weird West fiction, I encountered mostly twenty- to fortysomething, able-bodied, straight, Euro-American, cisgender men and women (mostly men) in largely stereotypical roles. I didn’t even see many Native American characters (perhaps as a response to Hollywood’s century-plus habit of confining Indian roles to savages, sidekicks, and/or corpses – http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/02/25/1189574/-A-Reprise-Savages-Sidekicks-American-Indians-in-Cinema-Part-I#).

Given the Grand Canyon-sized chasm between what I experienced and knew, and what I read, I found myself craving more diverse Weird West fiction, to the point that I found myself editing two volumes of Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West, and selecting the following stories for Volume One.

In “One-Eyed Jack,” Connie Wilkins uses the Weird West genre to examine the assumptions underlying some of the most popular Western archetypes and situations with her differently abled gunfighter and whip-handy brothel madam. In “What Happened at Blessing Creek,” Naomi Kritzer considers indigenous/immigrant relations and Manifest Destiny in a world of magic and shapeshifting. Magic and shapeshifting also play a role in Milton Davis’ “Kiowa Rising,” a steamfunk alternate history about an almost superheroically accomplished historical figure, the African-American U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves.

As it is in Western fiction, the savior archetype is common in Weird West fiction. In both genres, this archetype often takes the form of a lone, gun-toting, male drifter–someone straight and white and not only able-bodied, but supremely competent. Sometimes the savior is a frontier knight in shining armor, but more often he’s unreligious–even amoral. However, in Misha Nogha’s alternate history, “Assiniboia,” it’s a devout French Catholic priest who wants to save the souls of Indian and Métis…only to find himself in need of salvation. In Vivian Caethe’s steampunk alternate history, “The Noonday Sun,” a frontier knight in shining armor shatters the expectations of gender, ability, and sexual orientation. In his alternate-history fantasy, “A Scene from the Yaqui Wars,” Don Webb’s savior subverts the expectations of race and size.

Weird West fiction may incorporate archetypes and beings barred from direct participation in the mundane Western. In Steve Berman’s “Wagers of Gold Mountain,” a Chinese immigrant faces trickster spirits from East and West. In Rudy Ch. Garcia’s “How Five-Gashes-Tumbling Chaneco Earned the Nickname,” a Conquistador’s expeditionary army encounters shamans and nagual spirits. In an excerpt from Ken Liu’s novella, “All the Flavors,” the Idaho gold rush draws a Chinese god. And uranium attracts attention from beyond the stars in Kathleen Alcalá’s “Midnight at the Lariat Lounge.”

Reconstructive study of history finds no shortage of homosexual relationships or gender variance in the Old West. The male buddy pairs in Wild West movies and fiction do not lack in homoerotic undertones. However, open same-sex relationships were not necessarily welcome in the Old West, as Gemma Files reveals in “Sown From Salt,” her grimdark horror story of the aftermath of a couple’s deadly breakup, and gender reassignment did not guarantee a long and joyful life, as a Native girl learns when she is assigned to a traditionally male role in Carol Hightshoe’s “Wolves of the Comanchería.” Between the California and Alaska gold rushes, a lesbian couple in Nicole Kornher-Stace’s “Deal” draws the unwelcome attention of Pinkerton agents. And in Scott A. Cupp’s “Thirteen Days of Glory,” one of the archetypal battles of the Old West centers on the right of man to be with another man.

Some states are viewed as quintessentially Western–Arizona, Montana, Texas, and Wyoming spring instantly to mind. Perhaps because of unique elements in its journey to territory and state, New Mexico features far less often in Western fiction; but Nicole Givens Kurtz’s supernatural revenge story, “Justice,” is a quintessentially New Mexico and quintessentially Weird West tale. California too is somewhat underutilized in Weird West fiction, perhaps because it became a state much earlier than most Western territories, or perhaps because it was put under the rule of U.S. law much earlier. But its high arid mountains are the perfect venue for a post-apocalyptic scientist-outlaw’s hideout and bounty hunter’s search in Beth Wodzinski’s steampunk “Suffer Water,” and its high desert is a natural setting for the zombiepocalypse of Cynthia Ward’s “#rising.”

The Western frontier was not a fixed border or region, nor was it confined to the contiguous United States. Misha Nogha’s “Assiniboia” concerns a proposed Canadian province that was stillborn in our timeline. In J. Comer’s “Soldier’s Coat,” a steampunk war between Russia and the United States plays out in Alaska. In Carole McDonnell’s time travel fantasy, “A Thing of Beauty,” a modern black Catholic priest finds himself in the pre-Civil War territory of Kansas, while a mixed-race girl fleeing an unwanted marriage lights out from Missouri for the land rush in Oklahoma Territory, in Rebecca McFarland Kyle’s steampunk fantasy, “Cross the River.” It is in Arizona Territory that Edward M. Erdelac’s Hasidic lone drifter faces an ancient supernatural threat, in an excerpt from “The Blood Libel,” and it is in Mexico that a steampunk airship fleet rises against the United States, in Ernest Hogan’s “Pancho Villa’s Flying Circus.”

No anthology (or pair of anthologies) can capture all the complex sociocultural realities of a historical era, but I hope Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West: Volume One suggests them, and entertainingly.”

Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West: Volume One is available from Amazon.

Text copyright Cynthia Ward and Weird Westerns 2015.