Classics and the Western Canon discussion

Divine Comedy, Dante

>

Paradiso 10: The Sun and the Twelve Wise Men

http://www.lockportstreetgallery.com/...

http://www.lockportstreetgallery.com/...

Salvador Dali: Paradiso Canto 10. “The Song of the Wise Spirits.”

Like the trumpet.

http://www.ivodavidfineart.com/images...

http://www.ivodavidfineart.com/images...

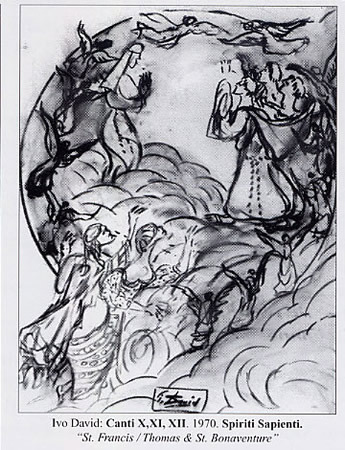

Ivo David: Paradiso Canto X, XI, XII. “Spiriti Sapienti.” 1970.

Aquinas on the upper left, I presume.

(Slightly clearer image:) http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

(Slightly clearer image:) http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...Sandro Botticelli: Paradiso Canto X.1. “Ascent to the Fourth Planetary Sphere (Heaven of the Sun); The Light of Thomas Aquinas Acts as Dante's Guide to the Heaven of the Wise.” c.1480 - c.1495. Drawing.

http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

John Flaxman: Paradiso Canto X.52. “The Angels’ Sun.” 1793. Engraving.

http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

Giovanni di Paolo: Paradiso Canto 10.40. “Dante and Beatrice Ascend to the Heaven of the Sun.” c.1450. Manuscript illumination. Yates Thompson 36. British Library.

http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

Giovanni di Paolo: Paradiso Canto 10.94. “St. Thomas Introduces Dante to Other Souls in the Heaven of the Sun.” c.1450. Manuscript illumination. Yates Thompson 36. British Library.

Can one now presume from this Beatrice is in blue, and Dante wears the close fitting cap behind her?

I really like this second one for this Canto.

(Images for Cantos X-XV did not exist or are not available for the Bodleian Library manuscript. Nor are there images from Doré or Blake here.)

http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp...

http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp...

Amos Nattini, Paradiso Canto X. "Guardando nel suo Figlio con l'Amore.” 1923. (First line. In Hollander translation, that becomes “Gazing on His Son with the love…”)

Laurele wrote: "Such a beautiful canto! How many of the wise guys do you know?"

Laurele wrote: "Such a beautiful canto! How many of the wise guys do you know?"I know only a few of the wise men, so there is opportunity for lots of learning here. Right now, look forward especially to the names I recognize without knowing their works.

For consideration of whom Dante might have chosen as his twelve wise men, this is an interesting list: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doctor_o...

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

Illustration of Dante's Paradiso, Canto X, First Circle of the 12 Teachers of Wisdom Led by Thomas Aquinas.

Manuscript: Copenhagen, The Royal Library, MS Thott 411.2 (15th century)

("Siger of Brabant is depicted with red cloak, top right.")

What fun! Another manuscript!

Here the blessed are collected according to their preeminent virtue, wisdom, rather than their failing. How odd.

Here the blessed are collected according to their preeminent virtue, wisdom, rather than their failing. How odd.

Roger wrote: "Here the blessed are collected according to their preeminent virtue, wisdom, rather than their failing. How odd."

Roger wrote: "Here the blessed are collected according to their preeminent virtue, wisdom, rather than their failing. How odd."But what an interesting set of wisdom. (Just indulged in a quick survey.) Still, certainly destroys earlier hypotheses we made on why organized by shortcomings?

Lily wrote: "http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

Lily wrote: "http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...Giovanni di Paolo: Paradiso Canto 10.40. “Dante and Beatrice Ascend to the Heaven of the Sun.” c.1450. Manuscript illumination. Yates..."

Notice the mansions they are leaving behind in the first picture. Are they hotels where the souls stay when they descend to their representative planet to speak with tourists?

You can identify Beatrice as a holy woman by the white scarf she wears under her head covering. You can just see it coming over her ears and down under her chin.

Roger wrote: "Here the blessed are collected according to their preeminent virtue, wisdom, rather than their failing. How odd."

Roger wrote: "Here the blessed are collected according to their preeminent virtue, wisdom, rather than their failing. How odd."Interesting. Is it because we are going higher?

Lily, our Researcher in Chief, has kindly pulled together some information about the Twelve Wise Men. Here are the first two:

Lily, our Researcher in Chief, has kindly pulled together some information about the Twelve Wise Men. Here are the first two:1. Albertus Magnus (ca. 1193-1280)

“Albertus was the first to comment on virtually all of the writings of Aristotle, thus making them accessible to wider academic debate. The study of Aristotle brought him to study and comment on the teachings of Muslim academics, notably Avicenna and Averroes, and this would bring him in the heart of academic debate. He was ahead of his time in his attitude towards science.”.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albertus...

2. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

“…an Italian Dominican priest, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, within which he is also known as the "Dumb Ox", "Angelic Doctor", "Doctor Communis", and "Doctor Universalis"…. Thomas came from one of the noblest families of the Kingdom of Naples, with the title of "counts of Aquino". He was the foremost classical proponent of natural theology, and the father of Thomism. His influence on Western thought is considerable, and much of modern philosophy was conceived in development or refutation of his ideas, particularly in the areas of ethics, natural law, metaphysics, and political theory.

“Thomas is held in the Roman Catholic Church to be the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood, and indeed the highest expression of both natural reason and speculative theology. The study of his works, according to papal and magisterial documents, is a core of the required program of study for those seeking ordination as priests or deacons, as well as for those in religious formation and for other students of the sacred disciplines (Catholic philosophy, theology, history, liturgy, and canon law).[2] The works for which he is best-known are the Summa theologiae and the Summa Contra Gentiles. One of the 35 Doctors of the Church, he is considered the Church's greatest theologian and philosopher.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_A...

More from Lily. Can anyone help on number three?

More from Lily. Can anyone help on number three?3. Francesco Graziano (ca. 1090-1164)

4. Peter Lombard (ca. 1095-1160)

“…a scholastic theologian and bishop and author of Four Books of Sentences, which became the standard textbook of theology, for which he earned the accolade Magister Sententiarum.”

Peter Lombard wrote commentaries on the Psalms and the Pauline epistles; however, his most famous work by far was Libri Quatuor Sententiarum, or the Four Books of Sentences, which became the standard textbook of theology at the medieval universities.[15] From the 1220s until the 16th century, no work of Christian literature, except for the Bible itself, was commented upon more frequently. All the major medieval thinkers, from Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas to William of Ockham and Gabriel Biel, were influenced by it. Even the young Martin Luther still wrote glosses on the Sentences, and John Calvin quoted from it over 100 times in his Institutes.

Though the Four Books of Sentences formed the framework upon which four centuries of scholastic interpretation of Christian dogma was based, rather than a dialectical work itself, the Four Books of Sentences is a compilation of biblical texts, together with relevant passages from the Church Fathers and many medieval thinkers, on virtually the entire field of Christian theology as it was understood at the time. Peter Lombard's magnum opus stands squarely within the pre-scholastic exegesis of biblical passages, in the tradition of Anselm of Laon, who taught through quotations from authorities.[16] It stands out as the first major effort to bring together commentaries on the full range of theological issues, arrange the material in a systematic order, and attempt to reconcile them where they appeared to defend different viewpoints. The Sentences starts with the Trinity in Book I, moves on to creation in Book II, treats Christ, the saviour of the fallen creation, in Book III, and deals with the sacraments, which mediate Christ's grace, in Book IV.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Lo...

Lily wrote: "http://www.lockportstreetgallery.com/...

Salvador Dali: Paradiso Canto 10. “The Song of the Wise Spirits.”

Like the trumpet."

I like this one, too, Lily. Here's what it says to me:

(view spoiler)

Salvador Dali: Paradiso Canto 10. “The Song of the Wise Spirits.”

Like the trumpet."

I like this one, too, Lily. Here's what it says to me:

(view spoiler)

From Lily:

From Lily:5. King Solomon (author of four books of the Bible)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Sol...

6. Dionysius the Areopagite (converted by St. Paul)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dionysiu...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudo-D...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Areopagus

7. Paulus Orosius (active first half of fifth cent.)

7. Paulus Orosius (active first half of fifth cent.) a priest, Christian historian, theologian and student of Saint Augustine of Hippo. It is possible that he was born in Bracara Augusta (which is now known as Braga, Portugal).[2] Although there are some question marks regarding his biography, such as his exact date of birth, it is known that he was a person of some prestige from a cultural point of view, as he had contact with the greatest figures of his time such as Saint Augustine of Hippo and Saint Jerome. In order to meet with them Orosius travelled to cities on the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, such as Hippo Regius and Alexandria.

These journeys defined his life and intellectual output. Orosius did not just discuss theological matters with Saint Augustine, in fact he also collaborated with him on the book The City of God.[3] In addition, in 415 he was chosen to travel to Palestine in order to exchange information with other intellectuals. He was also able to participate in a Church Council meeting in Jerusalem on the same trip and he was entrusted with transporting the relics of Saint Stephen. The date of his death is also unclear, although it appears to have not been earlier than 418, when he finished one of his books, or later than 423.[4]

He wrote a total of three books, of which his most important is his Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII), considered to be one of the books with the greatest impact on historiography during the period between antiquity and the Middle Ages, as well as being one of the most important Hispanic books of all time. Part of its importance comes from the fact that the author shows his historiographical methodology. The book is a historical narration focussing on the pagan peoples from the earliest time up until the time Orosius was alive.[5]

Orosius was a highly influential figure both for the dissemination of information (History Against the Pagans was one of the main sources of information regarding Antiquity that was used up to the Renaissance) and for rationalising the study of history (his methodology greatly influenced later historians).[6][7]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paulus_O...

8. Severinus Boethius (ca. 475-525)

a philosopher of the early 6th century. He was born in Rome to an ancient and prominent family which included emperors Petronius Maximus and Olybrius and many consuls.[2] His father, Flavius Manlius Boethius, was consul in 487 after Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman Emperor. Boethius, of the noble Anicia family, entered public life at a young age and was already a senator by the age of 25.[4] Boethius himself was consul in 510 in the kingdom of the Ostrogoths. In 522 he saw his two sons become consuls.[5] Boethius was imprisoned and eventually executed by King Theodoric the Great,[6] who suspected him of conspiring with the Eastern Roman Empire. While jailed, Boethius composed his Consolation of Philosophy, a philosophical treatise on fortune, death, and other issues. The Consolation became one of the most popular and influential works of the Middle Ages. A link between Boethius and a mathematical boardgame Rithmomachia has been made.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Severinu...

9. Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636);

9. Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636); Archbishop of Seville for more than three decades and is considered, as the historian Montalembert put it in an oft-quoted phrase, "the last scholar of the ancient world".[1] Indeed, all the later medieval history-writing of Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal) was based on his histories.

At a time of disintegration of classical culture,[2] and aristocratic violence and illiteracy, he was involved in the conversion of the royal Visigothic Arians to Catholicism, both assisting his brother Leander of Seville, and continuing after his brother's death. He was influential in the inner circle of Sisebut, Visigothic king of Hispania. Like Leander, he played a prominent role in the Councils of Toledo and Seville. The Visigothic legislation that resulted from these councils is regarded by modern historians[who?] as exercising an important influence on the beginnings of representative government.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isidore_...

10. the Venerable Bede (674-735);

an English monk at the Northumbrian monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth and of its companion monastery, Saint Paul's, in modern Jarrow (see Monkwearmouth-Jarrow), both in the Kingdom of Northumbria. Bede's monastery had access to a superb library which included works by Eusebius and Orosius among many others.

He is well known as an author and scholar, and his most famous work, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) gained him the title "The Father of English History". In 1899, Bede was made a Doctor of the Church by Leo XIII, a position of theological significance; he is the only native of Great Britain to achieve this designation (Anselm of Canterbury, also a Doctor of the Church, was originally from Italy). Bede was moreover a skilled linguist and translator, and his work with the Latin and Greek writings of the early Church Fathers contributed significantly to English Christianity, making the writings much more accessible to his fellow Anglo-Saxons.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Vene...

11. Richard of St. Victor (ca. 1123-1173)

11. Richard of St. Victor (ca. 1123-1173) …known today as one of the most influential religious thinkers of his time. He was a prominent mystical theologian, and was prior of the famous Augustinian Abbey of Saint Victor in Paris from 1162 until his death in 1173.

Benjamin Minor (originally titled Book of the Twelve Patriarchs) and Benjamin Major are Richard of Saint Victor's great works on contemplation. It is not exactly known when these treatise were written, but both works would seem to date before 1162. Richard specifies that Benjamin Minor is not a treatise on contemplation but rather prepares the mind for contemplation.[10] He uses the story of Jacob and his clan to create a treatise on the psychology of vices and virtues. He uses the different elements of the tale to bring to light the relationship between the mind and the body, the senses and reason. By doing this he wishes to establish within the younger members of his community a scheme to discern right and wrong actions through the powers of the mind. It is almost as though Richard is teaching the basic principles of psychology combined with spiritual doctrine. The whole purpose of this text is to prepare his students for contemplation and for a union with God. Each chapter starts with a text which serves the idea of the writer and other texts are introduced to confirm his points.

The Benjamin Major completes this with the study of the mind in relation to prayer. However, in the last chapters of Benjamin Major, written later than the Minor, Richard almost abandons his topic and the discussion of the teaching of mystical theology takes up a good portion of every remaining chapter. He is still attempting to instruct his followers on a text but he has also engaged himself in creating a system of mystical theology.

One of Richard’s greatest works was the De Trinitate which was probably written close to the end of his life. This is known because it incorporates pieces of theological text which editors are now finding in earlier works.[11] De Trinitate is Richard's most independent and original study on dogmatic theology. It stems from the desire to show that dogmatic truths of Christian revelation are ultimately not against reason. Richard's theological approach stems from a profoundly mystical life of prayer, which in the Spirit seeks to involve the mind, in continuation with the Augustinian and Anselmian tradition.

Due to the fact that until recently this masterpiece has not been available in any English translation, its diffusion has been limited and its influence has never gone beyond 'Book III', condemning serious enquiry to an understanding of Richard's argument, which is only partial.[12] Finally, in 2011, through the efforts of Ruben Angelici's scholarship, the first, full translation of Richard's 'De Trinitate' has been released for publication in English and now this scholastic masterpiece is readily available to a wider audience to be appreciated in its entirety.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_...

12. Siger of Brabant (ca. 1225-ca. 1283)

…a 13th century philosopher from the southern Low Countries who was an important proponent of Averroism. He was considered a radical by the conservative members of the Roman Catholic Church, but it is suggested that he played as important a role as his contemporary Thomas Aquinas in the shaping of Western attitudes towards faith and reason.[citation needed]

Little is known about many of the details of his life. In 1266 he was attached to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Paris at the time when a riot erupted between the French and Picard "nations" of students—a series of loosely organized fraternities. The papal legate threatened Siger with execution as the ringleader of the Picard attack on the French, but no further action was taken. During the succeeding 10 years, he wrote the six works which are ascribed to him and were published under his name by Pierre Mandonnet in 1899. The titles of these treatises are:

De anima intellectiva (1270)

Quaestiones logicales

Quaestiones naturales

De aeternitate mundi

Quaestio utrum haec sit vera: Homo est animal nullo homine existente

Impossibilia

Averroism was controversial because it taught Aristotle in its original form with no reconciliation with Christian belief. Siger was accused of teaching "double truth"--that is, saying one thing could be true through reason, and that the opposite could be true through faith. Because Siger was a scholastic, he probably did not teach double truths but tried to find reconciliations between faith and reason.

In 1277 a general condemnation of Aristotelianism included a special clause directed against Boetius of Dacia and Siger of Brabant. Again Siger and Bernier de Nivelles were summoned to appear on a charge of heresy, especially in connection with the Impossibilia, where the existence of God is discussed. It appears, however, that Siger and Boetius fled to Italy and, according to John Peckham, archbishop of Canterbury, perished miserably.

The manner of Siger's death, which occurred at Orvieto, is not known. A Brabantine chronicle says that he was stabbed by an insane secretary (a clerico suo quasi dementi). The secretary is said to have used a pen as the murder weapon and his critics claimed since he had done so much damage with his pen, he deserved what was coming. Dante, in the Paradiso (x.134-6), says that he found "death slow in coming," and some have concluded that this indicates death by suicide. A 13th century sonnet by one Durante (xcii.9-14) says that he was executed at Orvieto: "a ghiado it fe' morire a gran dolore, Nella corte di Roma ad Orbivieto." The date of this may have been 1283-1284 when Pope Martin IV was in residence at Orvieto. His fellow radicals were lying low in the face of the Condemnations of 1277 and there was no investigation into his murder.

.

In politics he held that good laws were better than good rulers, and criticised papal infallibility in temporal affairs. The importance of Siger in philosophy lies in his acceptance of Averroism in its entirety, which drew upon him the opposition of Albertus Magnus and Aquinas. .

.

In December 1270 Averroism was condemned by ecclesiastical authority, and during his whole life Siger was exposed to persecution both from the Church and from purely philosophic opponents. In view of this, it is curious that Dante should place him in Paradise at the side of Aquinas and Isidore of Seville. Probably Dante knew of him only from the chronicler than as a persecuted philosopher.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siger_of...

@18 Adelle wrote: "2) The wings. So ragged. An indicator that wisdom doesn't come easily."

@18 Adelle wrote: "2) The wings. So ragged. An indicator that wisdom doesn't come easily."http://www.lockportstreetgallery.com/...

Salvador Dali: Paradiso Canto 10. “The Song of the Wise Spirits.”

Adelle -- the sheerness of the draperies suggested to me that when wisdom is achieved, it may have a sort of translucence, a sort of transparency. But it often takes a lot that is opaque to reach. (Classic example: E=mc squared)

Yeah! The Dalis speak to you, too!

Reynolds/Sayers:

Reynolds/Sayers:As in the Inferno and Purgatory, so now in Paradise, the tenth Canto constitutes the beginning of another section of the poem. To mark this division, there is a pause in the narrative, and what may be called a new prologue opens the Canto, recalling to our notice the ultimate theme of the whole work: the mystery of the Holy Trinity. In the allegory, the ascent beyond sense to the suprasensible symbolizes the progress of the soul in its advance towards knowledge of God, for it is by the illumination of the mind rather than by sense impressions that Dante comes ultimately to know Him.

Laurele wrote: "Reynolds/Sayers:

Laurele wrote: "Reynolds/Sayers:"...by the illumination of the mind rather than by sense impressions..."

Whatever that will turn out to mean.

Laurele wrote: "More from Lily. Can anyone help on number three?

Laurele wrote: "More from Lily. Can anyone help on number three?3. Francesco Graziano (ca. 1090-1164)

"

(GRATIANUS).

The little that is known concerning the author of the "Concordantia discordantium canonum", more generally called the "Decretum Gratiani", is furnished by that work itself, its earliest copies, and its twelfth-century "Summae" or abridgments.

Gratian was born in Italy, perhaps at Chiusi, in Tuscany. He became a Camaldolese monk (some say a Benedictine), and taught at Bologna in the monastery of SS. Felix and Nabor. Later, it was said that he was a brother of Peter Lombard, author of the "Liber Sententiarum", and of Peter Comestor, author of the "Historia Scholastica". Mediaeval scholars united in this way, by a fictive kinship, the three great contemporaries who seemed as the fathers the canon law, theology, and Biblical history. It is no less false to assert that he was a bishop. Nor is it certain at what time he compiled the "Decretum". It did not exist previous to 1139; for it contains decrees of the Second Lateran Council held in that year. A common opinion places its completion in 1151. Recent research, however, points to 1140, or to a date nearer thereto than to 1151. The "Decretum" was certainly known to Peter Lombard, for he makes use of it in his "Liber Sententiarum". Gratian died before the Third Lateran Council (1179), some say as early as 1160. It is not certain that he died at Bologna, though in that city a monument was erected to him in the church of St. Petronius. He is the true founder of the science of canon law.

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06730...

Any thoughts on why Dante chooses these particular wise men and not others? I'm particularly curious about the inclusion of Siger, who Thomas considered a heretic. Solomon also stands out against this assembly of church men.

Any thoughts on why Dante chooses these particular wise men and not others? I'm particularly curious about the inclusion of Siger, who Thomas considered a heretic. Solomon also stands out against this assembly of church men.

Thomas wrote: "Any thoughts on why Dante chooses these particular wise men and not others? I'm particularly curious about the inclusion of Siger, who Thomas considered a heretic. Solomon also stands out against t..."

Thomas wrote: "Any thoughts on why Dante chooses these particular wise men and not others? I'm particularly curious about the inclusion of Siger, who Thomas considered a heretic. Solomon also stands out against t..."Good question. There's more about the choice of Solomon in canto 13.

Thomas wrote: "Any thoughts on why Dante chooses these particular wise men and not others? I'm particularly curious about the inclusion of Siger, who Thomas considered a heretic. Solomon also stands out against t..."

Thomas wrote: "Any thoughts on why Dante chooses these particular wise men and not others? I'm particularly curious about the inclusion of Siger, who Thomas considered a heretic. Solomon also stands out against t..."This is the point where I'd like to know more biographical information about Dante, although I'm not really willing to make the investment to attain it, if even available. Your question was very much the one behind my comment in Msg 10.

My purely speculative response to your question about the inclusion of Siger comes from my own (faith) journey through the years -- one tries to soak up as much understanding as possible from the acknowledged "experts", but a some point, one can become a skeptic and can also explore the outlier thinkers, i.e., the heretics or those flirting with heresy, whatever that may mean.

(In today's world, as I have alluded elsewhere, searchers like Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan are among those playing such roles.

http://www.livingthequestions.com/xca...)

Do note that the article on Siger states:

"...He was considered a radical by the conservative members of the Roman Catholic Church, but it is suggested that he played as important a role as his contemporary Thomas Aquinas in the shaping of Western attitudes towards faith and reason.[citation needed]

and

"The importance of Siger in philosophy lies in his acceptance of Averroism in its entirety, which drew upon him the opposition of Albertus Magnus and Aquinas."

This suggests perhaps Dante's acceptance of (aspects of) Averroism?

Lily wrote: "(In today's world, as I have alluded elsewhere, searchers like Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan are among those playing such roles..."

Lily wrote: "(In today's world, as I have alluded elsewhere, searchers like Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan are among those playing such roles..."My kind of heretics, actually...

I still find Dante's inclusivity curious. I like the idea of an ecumenical Dante, but I'm not sure if it's justifiable. Maybe Siger reformed his views at some point?

Thomas wrote: "I still find Dante's inclusivity curious. I like the idea of an ecumenical Dante, but I'm not sure if it's justifiable. Maybe Siger reformed his views at some point? ..."

Thomas wrote: "I still find Dante's inclusivity curious. I like the idea of an ecumenical Dante, but I'm not sure if it's justifiable. Maybe Siger reformed his views at some point? ..."Doubtful, given his persecution and death story? But the part Aquinas objected to ("The term was used by the theologian Thomas Aquinas in a restricted sense to mean monopsychism and radical Aristotelianism.") probably were not the parts that attracted Dante nor those that influenced the faith.

From the transcript of Mazzotta's lecture on Canto X -- not a spoiler but long.

From the transcript of Mazzotta's lecture on Canto X -- not a spoiler but long.The quick version: "The reason why Dante rescues Siger of Brabant is a way for him to be ultimately thinking and making a statement that whatever we believe that is knowledge, it's never definite and it's always — we are literally on the way and rethinking it and making it all the time an object of our own self-critique."

(view spoiler)

Thomas/Mazotta wrote: whatever we believe that is knowledge, it's never definite and it's always — we are literally on the way and rethinking it and making it all the time an object of our own self-critique.

Thomas/Mazotta wrote: whatever we believe that is knowledge, it's never definite and it's always — we are literally on the way and rethinking it and making it all the time an object of our own self-critique.Sounds anachronistic to me, a rather 20th century way of thinking ... But I do wonder how serious accusations of heresy were taken (in more or less intellectual circles). I suppose everyone took for granted that they were often just an instrument in academic and other power struggles. Like Marxism in the Soviet Union. Something we could easily overlook because our sources would be silent about it.

Dante certainly seems to take heresy very seriously in Inferno, which is why I'm so surprised at Siger's place here in Paradise. It could be that Dante takes offense at certain types of heresy more than others, or it could be that he is having second thoughts about the severity of his judgement. This stanza from Canto XIII (which is largely a justification of Solomon's place among the stars) is interesting in this regard:

Dante certainly seems to take heresy very seriously in Inferno, which is why I'm so surprised at Siger's place here in Paradise. It could be that Dante takes offense at certain types of heresy more than others, or it could be that he is having second thoughts about the severity of his judgement. This stanza from Canto XIII (which is largely a justification of Solomon's place among the stars) is interesting in this regard: Moreover, let folk not be too secure in judgement, like one who should count the ears in the field before they are ripe; for I have seen first, all winter through, the thorn display itself hard and stiff, and then upon its summit bear the rose. And I have seen a ship ere now fare straight and swift over the sea through all her course, and perish at the last as she entered the harbor.

Thomas/Dante(Thomas) wrote: Moreover, let folk not be too secure in judgement ...

Thomas/Dante(Thomas) wrote: Moreover, let folk not be too secure in judgement ...I love that, and even more the finishing lines (Mandelbaum): Let not Dame Bertha or Master Martin think - that they have shared God's Counsel when they see - one rob and another who donates - the last may fall, the other may be saved

Dante knows how frail human judgement is (except maybe his own). And he is not the kind of man who enjoys smelling out heresy. His treatment of the heretic Farinata in Inferno X is even respectful (this may have been a case of poltical persecution though). Overall, heresy is not really an important theme in the Commedia, unlike simony for instance.

But recognition of the limitations of our judgement does not imply the idea that truth is changeable or relative - as is a suggested in the Mazzotta quote. I believe that would have been a strange and unacceptable concept to Dante.

Are we touching here on the use of dialectics for "determining" truth? Isn't this the Adriane's thread through Greek philosophy, Aristotle, Averroës, and scholasticism that eventually gets battered, but certainly not destroyed, by empiricism?

Are we touching here on the use of dialectics for "determining" truth? Isn't this the Adriane's thread through Greek philosophy, Aristotle, Averroës, and scholasticism that eventually gets battered, but certainly not destroyed, by empiricism?http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

Giovanni di Paolo: St. Thomas Aquinas Confounding Averroës.

(The artist also associated with the Yates manuscript.)

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

Averroës depicted in a painting by Italian artist Andrea di Bonaiuto. Florence, 14th century.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Averroes

"...Averroes had a greater impact on Western European circles [than Muslim] and he has been described as the 'founding father of secular thought in Western Europe'. The detailed commentaries on Aristotle earned Averroes the title 'The Commentator'. Latin translations of Averroes' work led the way to the popularization of Aristotle and were responsible for the development of scholasticism in medieval Europe."

Wendelman wrote: "But recognition of the limitations of our judgement does not imply the idea that truth is changeable or relative - as is a suggested in the Mazzotta quote.

Wendelman wrote: "But recognition of the limitations of our judgement does not imply the idea that truth is changeable or relative - as is a suggested in the Mazzotta quote. ."

Mazzotta is hard to follow sometimes, but I don't think he means to say here that Dante believes truth is relative. I think he's saying the discovery of "truth" is unfinished. It is a process, because the truths Siger seeks are "invidious" (in the Latin/Italian and not the English sense.) The truth is unseen in its totality.

Lily wrote: "Are we touching here on the use of dialectics for "determining" truth? Isn't this the Adriane's thread through Greek philosophy, Aristotle, Averroës, and scholasticism that eventually gets battere..."

Lily wrote: "Are we touching here on the use of dialectics for "determining" truth? Isn't this the Adriane's thread through Greek philosophy, Aristotle, Averroës, and scholasticism that eventually gets battere..."Yes! Dialectics as a discussion, a "talking through" or "talking across" something to get to the truth. (Though in the picture it looks like St. Thomas has just delivered a right cross and has concluded the conversation...)

Laurele wrote: "...Paulus Orosius (active first half of fifth cent.) a priest, Christian historian, theologian and student of Saint Augustine of Hippo...."

Laurele wrote: "...Paulus Orosius (active first half of fifth cent.) a priest, Christian historian, theologian and student of Saint Augustine of Hippo...."If you want a short exploration what is available readily of the writings of Paulus Orosius, go here for a few minutes:

http://www.amazon.com/s?ie=UTF8&f...

Lily wrote:'...Illustration of Dante's Paradiso, Canto X, First Circle of the 12 Teachers of Wisdom Led by Thomas Aqu..."

Lily wrote:'...Illustration of Dante's Paradiso, Canto X, First Circle of the 12 Teachers of Wisdom Led by Thomas Aqu...""Siger of Brabant is depicted with red cloak, top right."

Hmmm? Now which one is Thomas of Aquinas? Is he side by side with Sigar of Brabant in this painting of the 15th century, i.e., the 1400's?

Lily wrote: "

Lily wrote: "Hmmm? Now which one is Thomas of Aquinas?..."

Could be! I guess the two in black are the Dominicans, so one of them is Thomas and the other Albertus. I'm not sure which is which though.

Thomas wrote: ... the discovery of "truth" is unfinished. It is a process, because the truths Siger seeks are "invidious" (in the Latin/Italian and not the English sense.) The truth is unseen in its totality.

Thomas wrote: ... the discovery of "truth" is unfinished. It is a process, because the truths Siger seeks are "invidious" (in the Latin/Italian and not the English sense.) The truth is unseen in its totality. Okay, that makes more sense. A shy truth, only slowly unveiled in a long debate. We might like to imagine that was precisely the attraction of Siger for Dante: debate, not a monolithic system. But is in line with what we know of Dante's way of thinking? Actually, we don't even know how Dante understood Siger's philosophy (and the possible changes in it).

Concerning the painting: I read that Aquinas was obese, but it doesn't help much to identify him.

I love seeing Boethius again.

I love seeing Boethius again. While Dante does seem to favor Mediterranean wise men, it's nice the he stretched up to Britain, and close to Scotland (maybe even into what was at the time considered part of Scotland) to bring in the Venerable Bede. I have read a lot of history that references Bede, but have never read anything actually by him.

There continues to be a lot of singing in the Paradiso. I wonder whether any medieval choral group has done a CD of music from the Divine Comedy, singing canto by canto all the hymns and choral odes mentioned by Dante, much like book Lily mentioned that brings together the art of the Divine Comedy.

There continues to be a lot of singing in the Paradiso. I wonder whether any medieval choral group has done a CD of music from the Divine Comedy, singing canto by canto all the hymns and choral odes mentioned by Dante, much like book Lily mentioned that brings together the art of the Divine Comedy. I'm not surprised, though, by the amount of singing, since music was a central part of the Catholic liturgy.

Everyman wrote: "There continues to be a lot of singing in the Paradiso. I wonder whether any medieval choral group has done a CD of music from the Divine Comedy, singing canto by canto all the hymns and choral od..."

Everyman wrote: "There continues to be a lot of singing in the Paradiso. I wonder whether any medieval choral group has done a CD of music from the Divine Comedy, singing canto by canto all the hymns and choral od..."There is no music in Hell. This is not a CD, but its free.

http://www.worldofdante.org/music.html

I just happened to be going through some books in the garage today, attempting to sift the wheat from the chaff, when I stumbled across Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum. The introduction notes that the discovery of counterpoint was almost contemporary with the use of perspective in painting, which occurred around 1300. That seems to be a very approximate date, but it reminded me that the music of Dante's time would have been largely monophonic.

I just happened to be going through some books in the garage today, attempting to sift the wheat from the chaff, when I stumbled across Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum. The introduction notes that the discovery of counterpoint was almost contemporary with the use of perspective in painting, which occurred around 1300. That seems to be a very approximate date, but it reminded me that the music of Dante's time would have been largely monophonic.

Thomas wrote: "...The introduction notes that the discovery of counterpoint was almost contemporary with the use of perspective in painting, which occurred around 1300...."

Thomas wrote: "...The introduction notes that the discovery of counterpoint was almost contemporary with the use of perspective in painting, which occurred around 1300...."Thomas -- any particular reason for the phraseology "discovery of counterpoint" versus "the creation of counterpoint"? (My knowledge of music history is probably worse than nil. However, even for me, the Notre Dame web site can be fun to browse: the English version is eluding me right now, here is one French linkage: http://www.musique-sacree-notredamede... )

Another site on historic organs: http://mypipeorganhobby.blogspot.com/...

Ahh! English: http://www.notredamedeparis.fr/spip.p...

1-27 God's three Persons & Dante's addresses to his readers

1-6 Trinitarian prologue to the heaven of the Sun

7-15 address to the reader, urging attention to the stars

16-21 the effects of the Zodiac's ecliptic path on the earth

22-27 second address to the reader, urged to be self-sufficient

28-39 the ascent to the heaven of the Sun

28-33 the Sun, in Aries, seen as fructifying and measuring

34-39 both Dante's ascent and Beatrice's guidance seem timeless

40-138 the habitation of the Sun: first circle

40-48 the brightness within the Sun defeats Dante's telling

49-51 God exhibits His threefold "art"

52-54 Beatrice advises Dante to give thanks to the "sun of the angels" for allowing him to rise to the Sun

55-63 no mortal was then more devoted to God than Dante; his love for God eclipsed his love for Beatrice; her smile

64-69 the souls make a circle with Beatrice and Dante as center that is compared in simile to the

halo around the Moon

70-75 in the Empyrean, whence Dante has returned, there are "jewels" that these souls in the Sun now celebrate

76-81 the circling souls compared in simile to dancing ladies

82-96 Thomas Aquinas's first speech:

82-90 Since Dante's presence here reveals him to be one who lives in grace, Thomas must answer

his question,

91-93 which concerns the souls who are circling Beatrice;

94-96 the speaker identifies himself as a Dominican friar

97-99 (1) Albertus Magnus (ca. 1193-1280)

99 (2) Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

100-102 Thomas will now name the rest of the twelve:

103-105 (3) Francesco Graziano (ca. 1090-ca. 1160)

106-108 (4) Peter Lombard (ca. 1095-1160)

109-114 (5) King Solomon (author of four books of the Bible)

115-117 (6) Dionysius the Areopagite (converted by St. Paul)

118-120 (7) Paulus Orosius (active first half of fifth cent.)

121-123 the importance of the next soul is underlined

124-129 (8) Severinus Boethius (ca. 475-525)

130-132 (9) Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636);

(10) the Venerable Bede (674-735);

(11) Richard of St. Victor (ca. 1123-1173)

133-138 (12) Siger of Brabant (ca. 1225-ca. 1283)

139-148 coda: simile (mechanical clock calling monks to matins).