The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP, Chp. 12-14

The next chapter takes us into the fictitious borough of Eatanswill, which was probably some allusion more or less openly recognizable to Dickens’s contemporaries. Let’s not forget that he was a parliamentary reporter and as such very familiar with the verbiage of politicians of his day and age, and so the very first sentence of the chapter promises us an excursion into the realms of political satire:

In a way, I felt reminded of Gulliver’s Travels, another satirical travelogue, which likewise set its scene in fictitious places and probably invited readers to merry guessing-games of who was meant by a certain character and what particular question was alluded to by this or that detail. Ironically, the chronicler’s confession that he “had never heard of Eatanswill” also seems to imply that, however important Eatanswill might take itself, its fame has not spread very widely after all.

Be that as it may, our friends find themselves in that very place, which is divided along the lines of the Blues and the Buffs, two parties we do not learn anything particular about but that their members are at daggers drawn with each other and that whatever one party might suggest will meet with undaunted and bitter opposition from the other party. Those two parties are headed by the Honourable Samuel Slumkey of Slumkey Hall, for the Blues, and Horatio Fizkin, Esq., of Fizkin Lodge, for the Buffs, and at present there are the elections in which both gentlemen are vying for a seat in the House of Commons. As it happens, Mr Pickwick, through his connection with Mr Perker, and not so much through any political leanings of his own, falls in with the Blue Party, and upon arriving on the scene, he is introduced to Mr Pott, the editor of the Eatanswill Gazette, which is fighting for Blue principles and bitterly opposes the Buff propaganda of the Eatanswill Independent.

The chapter does not really have a lot of plot, but a lot of satire-ridden action. While Mr Tupman and Mr Snodgrass, together with Sam Weller, take up quarters at the Peacock Inn, Mr Pickwick and Mr Winkle are guests at Mr Pott’s house, and the careful reader may realize the signs of coming trouble on the wall because Mrs Pott does not appear to hold her husband, or at least his untiring endeavours to serve the Blue cause, in high esteem but rather views them with conjugal disdain, as her snide remarks show:

Apart from that, she takes a lively interest in Mr Winkle and indulges in the pleasure of this sportsman’s company, and we also learn – how, I cannot figure out – that on going to bed, Mr Winkle’s inner eye is feasting on the image of his host’s wife, which is not too propitious an omen for a long and peaceful sojourn at the Potts’ house.

Do you think we are going to hear of trouble arising for Mr Winkle?

The bulk of the chapter is dedicated to the Eatanswill elections, which are completely different from modern day elections in that they seem a very wild enterprise, with the opponent’s band playing on purpose to drown the rival orator’s voice in a sea of noise. What I knew in an abstract sort of way but what struck me as odd when reading this chapter was that elections at that time were not secret, but an open count of raised arms, and that only in the case of a lack of clear majorities was there a count of ballots. According to my notes in the Penguin edition, secret votings as a rule were only implemented by the Ballot Act in 1872. Especially in country boroughs, this must have come as a blow to rich landowners who could, till then, see whether their tenants, if they were entitled to vote, gave their vote for the “right” candidate. When Dickens describes the Hustings at Eatanswill, we are back into his Sketches again for he is clearly not interested in its potential for the plot itself but just sees the episode as a good opportunity for political satire. For example, we learn about how the respective parties try to influence voters in their favour, and some of these methods sound definitely familiar, viz. the practice of giving voters stickers, balloons, ball-point pens and other cheap junk with the party name imprinted on it. In this case, it is parasols, which at least come in useful. Then there is the issue of creating a positive public image for the candidate, and we can see Mr Perker as the prototype of the spin doctor, as the following brilliant passage shows:

This shows Dickens as a very fine observer – who doubted it? –, and if you know Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, you might feel reminded of one of the first scenes of the film. Other methods employed are probably not so common any more – at least, let’s hope so. We learn, for instance, that coachmen – Mr Weller’s own father, for one – are bribed to see to it that coaches carrying voters for the opposing party will not arrive in time because they have … ahem … accidents. Then we are told of other voters being made drunk or put to sleep with the help of laudanum to keep them away from the Hustings, and this made me ask myself whether Dickens allowed himself to be carried away by his exuberant imagination or whether this was really common practice. I have a feeling that the latter might have been the case.

All in all, I really enjoyed this satirical glimpse into policy a lot. What do you think about it? Do you think that the action is moving too slowly and that the novel is too episodic? Do you think Sam Weller and his stories – here the one about his father, which is quite morbid, considering that one old gentleman never showed up again after the coach fell into the river – entertaining and enriching to the story? And what do you make of the following wisdom voiced by Mr Pickwick:

”We will frankly acknowledge that, up to the period of our being first immersed in the voluminous papers of the Pickwick Club, we had never heard of Eatanswill; we will with equal candour admit that we have in vain searched for proof of the actual existence of such a place at the present day.”

In a way, I felt reminded of Gulliver’s Travels, another satirical travelogue, which likewise set its scene in fictitious places and probably invited readers to merry guessing-games of who was meant by a certain character and what particular question was alluded to by this or that detail. Ironically, the chronicler’s confession that he “had never heard of Eatanswill” also seems to imply that, however important Eatanswill might take itself, its fame has not spread very widely after all.

Be that as it may, our friends find themselves in that very place, which is divided along the lines of the Blues and the Buffs, two parties we do not learn anything particular about but that their members are at daggers drawn with each other and that whatever one party might suggest will meet with undaunted and bitter opposition from the other party. Those two parties are headed by the Honourable Samuel Slumkey of Slumkey Hall, for the Blues, and Horatio Fizkin, Esq., of Fizkin Lodge, for the Buffs, and at present there are the elections in which both gentlemen are vying for a seat in the House of Commons. As it happens, Mr Pickwick, through his connection with Mr Perker, and not so much through any political leanings of his own, falls in with the Blue Party, and upon arriving on the scene, he is introduced to Mr Pott, the editor of the Eatanswill Gazette, which is fighting for Blue principles and bitterly opposes the Buff propaganda of the Eatanswill Independent.

The chapter does not really have a lot of plot, but a lot of satire-ridden action. While Mr Tupman and Mr Snodgrass, together with Sam Weller, take up quarters at the Peacock Inn, Mr Pickwick and Mr Winkle are guests at Mr Pott’s house, and the careful reader may realize the signs of coming trouble on the wall because Mrs Pott does not appear to hold her husband, or at least his untiring endeavours to serve the Blue cause, in high esteem but rather views them with conjugal disdain, as her snide remarks show:

”‘I wish, my dear, you would endeavour to find some topic of conversation in which these gentlemen might take some rational interest.’

‘But, my love,’ said Mr. Pott, with great humility, ‘Mr. Pickwick does take an interest in it.’

‘It’s well for him if he can,’ said Mrs. Pott emphatically; ‘I am wearied out of my life with your politics, and quarrels with the Independent, and nonsense. I am quite astonished, P., at your making such an exhibition of your absurdity.’”

Apart from that, she takes a lively interest in Mr Winkle and indulges in the pleasure of this sportsman’s company, and we also learn – how, I cannot figure out – that on going to bed, Mr Winkle’s inner eye is feasting on the image of his host’s wife, which is not too propitious an omen for a long and peaceful sojourn at the Potts’ house.

Do you think we are going to hear of trouble arising for Mr Winkle?

The bulk of the chapter is dedicated to the Eatanswill elections, which are completely different from modern day elections in that they seem a very wild enterprise, with the opponent’s band playing on purpose to drown the rival orator’s voice in a sea of noise. What I knew in an abstract sort of way but what struck me as odd when reading this chapter was that elections at that time were not secret, but an open count of raised arms, and that only in the case of a lack of clear majorities was there a count of ballots. According to my notes in the Penguin edition, secret votings as a rule were only implemented by the Ballot Act in 1872. Especially in country boroughs, this must have come as a blow to rich landowners who could, till then, see whether their tenants, if they were entitled to vote, gave their vote for the “right” candidate. When Dickens describes the Hustings at Eatanswill, we are back into his Sketches again for he is clearly not interested in its potential for the plot itself but just sees the episode as a good opportunity for political satire. For example, we learn about how the respective parties try to influence voters in their favour, and some of these methods sound definitely familiar, viz. the practice of giving voters stickers, balloons, ball-point pens and other cheap junk with the party name imprinted on it. In this case, it is parasols, which at least come in useful. Then there is the issue of creating a positive public image for the candidate, and we can see Mr Perker as the prototype of the spin doctor, as the following brilliant passage shows:

”‘Is everything ready?’ said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey to Mr. Perker.

‘Everything, my dear Sir,’ was the little man’s reply.

‘Nothing has been omitted, I hope?’ said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

‘Nothing has been left undone, my dear sir—nothing whatever. There are twenty washed men at the street door for you to shake hands with; and six children in arms that you’re to pat on the head, and inquire the age of; be particular about the children, my dear sir—it has always a great effect, that sort of thing.’

‘I’ll take care,’ said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

‘And, perhaps, my dear Sir,’ said the cautious little man, ‘perhaps if you could—I don’t mean to say it’s indispensable—but if you could manage to kiss one of ‘em, it would produce a very great impression on the crowd.’

‘Wouldn’t it have as good an effect if the proposer or seconder did that?’ said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

‘Why, I am afraid it wouldn’t,’ replied the agent; ‘if it were done by yourself, my dear Sir, I think it would make you very popular.’

‘Very well,’ said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, with a resigned air, ‘then it must be done. That’s all.’”

This shows Dickens as a very fine observer – who doubted it? –, and if you know Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, you might feel reminded of one of the first scenes of the film. Other methods employed are probably not so common any more – at least, let’s hope so. We learn, for instance, that coachmen – Mr Weller’s own father, for one – are bribed to see to it that coaches carrying voters for the opposing party will not arrive in time because they have … ahem … accidents. Then we are told of other voters being made drunk or put to sleep with the help of laudanum to keep them away from the Hustings, and this made me ask myself whether Dickens allowed himself to be carried away by his exuberant imagination or whether this was really common practice. I have a feeling that the latter might have been the case.

All in all, I really enjoyed this satirical glimpse into policy a lot. What do you think about it? Do you think that the action is moving too slowly and that the novel is too episodic? Do you think Sam Weller and his stories – here the one about his father, which is quite morbid, considering that one old gentleman never showed up again after the coach fell into the river – entertaining and enriching to the story? And what do you make of the following wisdom voiced by Mr Pickwick:

”‘Who is Slumkey?’ whispered Mr. Tupman.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Mr. Pickwick, in the same tone. ‘Hush. Don’t ask any questions. It’s always best on these occasions to do what the mob do.’

‘But suppose there are two mobs?’ suggested Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Shout with the largest,’ replied Mr. Pickwick.”

Chapter 14 provides another example of sideline entertainment in that it does not at all contribute to the action but tells us of the evenings Mr Tupman – I can hardly resist calling him Tuppy – and Mr Snodgrass spend in the commercial room of the Peacock, where there is always a circle of guests, most of them bagmen or other people travelling from place to place and exchange stories or bits of everyday philosophy. We don’t get the names of any of these men here, which is clearly indicative of their not being relevant to any further events the story might bring, but it’s great to see how Dickens describes them in a few strokes and makes them distinguishable from one another: There is “a stout, hale personage of about forty, with only one eye—a very bright black eye, which twinkled with a roguish expression of fun and good-humour” – possibly a more benevolent brother of Mr Squeers? –, and that is all you need to know about him. He is going to tell the Bagman’s Story, which is the heart and soul of this chapter, in a few moments. Then there is “a very red-faced man, behind a cigar”, and these few words, through the way they are put, suffice to conjure up the image of an apoplectic middle-aged gentleman, whose face is hidden behind a big cigar and clouds of smoke. Of course, no round would be complete – at least not in Dickens, if you remember Sir Mulberry Hawk’s sycophants, Mr Willet’s cronies, or the three-headed choir at the Veneering dinner table – without “a man of bland voice and placid countenance, who always made it a point to agree with everybody.”

It’s astonishing how Dickens manages to bring all these characters to life with a few strokes of his brush, and how important it seems to him, although they are only granted a brief spell of time on the stage of this novel (or whatever you may want to call it). I was also led to another reflection, namely how nice and cosy it must have been in those old guest-rooms when people did not sit isolated, checking their whatsapp messages all night long but were actually talking to each other, whiling away their few leisure hours by talking to each other and telling stories. I wonder whether they really told a lot of stories, and if so, how good they were at it. Probably, there really was an art of story-telling, i.e. telling them in a way that held the listeners’ interest for an hour or so. Is this really a glimpse into a world that existed as it is described, or is it a purely literal convention?

The Bagman’s Story itself is completely different in tone from any of the stories we have got so far – light-hearted, quaint and not taking itself too seriously. It can be quickly summarized by saying that it is about a bagman called Tom Smart – the name fits him to a T –, who comes to an inn which is kept by a comely widow who has an annoying suitor – annoying to Tom, that is. Tom thinks that the inn would be an admirable place to take care of, and the widow would be an admirable wife into the bargain, but alas! there is this other suitor, and so Tom can hardly get his foot into the door. At night, however, an old-fashioned chair in Tom’s bedroom comes to life – that sounds a bit like a Disney movie – and encourages Tom to throw his hat into the ring (as we say in Germany) and fight for the landlady. The chair gives him the necessary ammunition by pointing out a letter in one of the pockets of a pair of trousers belonging to his rival, which are, by whatever coincidence, lying in the cupboard in his room. This letter gives proof that his rival is already married to another woman, and with the help of this information, Tom can out-Tom the annoying suitor and eventually win the widow’s hand (and inn). On the whole, I found it difficult to say whether I liked the story or not, because while it is very pleasant to read aloud – Dickens gives the chair a very distinctive voice of its own, and it’s funny to see how it always inserts the direct address “Tom” into its sentences, thus cowing Tom to a certain extent and exacting respect from him –, yet the solution is all too pat. At the same time, the story seems to make a tongue-in-cheek comment on Tom’s (and other people’s) mercenary view on marriage. What are your impressions of this strange story?

It’s astonishing how Dickens manages to bring all these characters to life with a few strokes of his brush, and how important it seems to him, although they are only granted a brief spell of time on the stage of this novel (or whatever you may want to call it). I was also led to another reflection, namely how nice and cosy it must have been in those old guest-rooms when people did not sit isolated, checking their whatsapp messages all night long but were actually talking to each other, whiling away their few leisure hours by talking to each other and telling stories. I wonder whether they really told a lot of stories, and if so, how good they were at it. Probably, there really was an art of story-telling, i.e. telling them in a way that held the listeners’ interest for an hour or so. Is this really a glimpse into a world that existed as it is described, or is it a purely literal convention?

The Bagman’s Story itself is completely different in tone from any of the stories we have got so far – light-hearted, quaint and not taking itself too seriously. It can be quickly summarized by saying that it is about a bagman called Tom Smart – the name fits him to a T –, who comes to an inn which is kept by a comely widow who has an annoying suitor – annoying to Tom, that is. Tom thinks that the inn would be an admirable place to take care of, and the widow would be an admirable wife into the bargain, but alas! there is this other suitor, and so Tom can hardly get his foot into the door. At night, however, an old-fashioned chair in Tom’s bedroom comes to life – that sounds a bit like a Disney movie – and encourages Tom to throw his hat into the ring (as we say in Germany) and fight for the landlady. The chair gives him the necessary ammunition by pointing out a letter in one of the pockets of a pair of trousers belonging to his rival, which are, by whatever coincidence, lying in the cupboard in his room. This letter gives proof that his rival is already married to another woman, and with the help of this information, Tom can out-Tom the annoying suitor and eventually win the widow’s hand (and inn). On the whole, I found it difficult to say whether I liked the story or not, because while it is very pleasant to read aloud – Dickens gives the chair a very distinctive voice of its own, and it’s funny to see how it always inserts the direct address “Tom” into its sentences, thus cowing Tom to a certain extent and exacting respect from him –, yet the solution is all too pat. At the same time, the story seems to make a tongue-in-cheek comment on Tom’s (and other people’s) mercenary view on marriage. What are your impressions of this strange story?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 14 provides another example of sideline entertainment in that it does not at all contribute to the action but tells us of the evenings Mr Tupman – I can hardly resist calling him Tuppy – an..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 14 provides another example of sideline entertainment in that it does not at all contribute to the action but tells us of the evenings Mr Tupman – I can hardly resist calling him Tuppy – an..."As sideline entertainment goes, I was pleased to have gotten away from the darker, crueler subject matter. This story had enough whimsy in it to fit in better with the rest of the novel; I didn't find it as jarring.

Tristram, at a recent staff day for our library system, one of our breakout sessions was a presentation by a professional storyteller. Good oral storytelling is a dying art, I'm afraid. It's certainly not a talent I was born with, nor do I think I could develop the necessary skills. I can only think of one famous oral storyteller in my lifetime - Andy Griffith. His stories, of course, were scripted, so I don't even know if we can count them. I'm sure there are others, but I can't come up with any.

One of Griffith's famous bits was a retelling of Romeo and Juliet, which they worked into a script for The Andy Griffith Show. The scene showcases his wonderful storytelling skills.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ACx8...

When my son was younger, I once went with him to a lady who tells fairy tales: She usually comes to our town in autumn and winter and tells her stories, or rather those collected by the Brothers Grimm, at the hearth of an old farm house where she makes a real fire and tells stories until the final log has burnt up, which happens sooner than I would like it to. I asked her once how she came to story-telling, and she explained to me that she started as an actress but now has turned to telling fairy tales. She surely has a way with words, but it is not only that; she also has a talent of imitating voices and of conjuring up different moods with her voice. I can tell you a really good story-teller can be as entertaining as a movie!

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Curiosities,

In the instalment we are going to discuss this week, Mr Pickwick’s adventures seem to be taking a slightly different turn even though at first sight, everything seems to b..."

Tristram

You lead us, well me anyway, into a possible new world of lists and sightings. With the Bardell-Pickwick misinterpretations of love signals we have yet another example of love that goes either right, on occasion, or wrong, seemingly every chapter. With very few birds to take note of, perhaps a listing of love bird follies might be in order.

Then you introduce the concept of Wellerisms. Thanks for the great examples. As I have been preparing my coming chapters I have been noting the Wellerisms to myself. Following your lead, I think I too will create a list of them at the end of each chapter when I find one. Perhaps other Curiosities will help in the great Wellerism hunt as well. Why enjoy “Where’s Waldo” when we can have Wellerisms?

In the instalment we are going to discuss this week, Mr Pickwick’s adventures seem to be taking a slightly different turn even though at first sight, everything seems to b..."

Tristram

You lead us, well me anyway, into a possible new world of lists and sightings. With the Bardell-Pickwick misinterpretations of love signals we have yet another example of love that goes either right, on occasion, or wrong, seemingly every chapter. With very few birds to take note of, perhaps a listing of love bird follies might be in order.

Then you introduce the concept of Wellerisms. Thanks for the great examples. As I have been preparing my coming chapters I have been noting the Wellerisms to myself. Following your lead, I think I too will create a list of them at the end of each chapter when I find one. Perhaps other Curiosities will help in the great Wellerism hunt as well. Why enjoy “Where’s Waldo” when we can have Wellerisms?

Tristram wrote: "The next chapter takes us into the fictitious borough of Eatanswill, which was probably some allusion more or less openly recognizable to Dickens’s contemporaries. Let’s not forget that he was a pa..."

Tristram

“Shout with the loudest.” Seems like such advice is still followed today. Perhaps the only slight alteration would be “try to be the loudest shouter.” Civility seems to be lost in too many discussions today.

You ask if the action is moving too slowly or if the novel is too episodic. I am asking myself that as well. When we were reading Sketches By Boz we knew we were reading individual stories. Thus, each story was in itself, self-contained. I find that most of the chapters so far in PP could well stand on their own. I think to Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford. It too originally set out to be episodes of the widows in the town of Cranford. With a bit of fitting, those individual stories do blend into a novel of sorts.

With the coming of Sam Weller we have a glue point to which the narrative of Pickwick can find some stronger foundation. Still, since the activity and the mandate of the Pickwick Club seems to be to wander about, and both get into bits of trouble and adventure and then get out of them, we are lacking a foundation. Dickens did much with great skill, but perhaps what he did best was to create a sense of place in his later novels. London, of course, was his heart, but the marsh country of Pip and the cloistered town of The Mystery of Edwin Drood and other settings are deep and rich veins of blood that ground our reading. In PP we have, as yet, no base, no foundation, no central point around which to build a story.

My feeling is that we still have a picaresque novel. I agree with your observations on Gulliver’s Travels. The key word is “Travels.” It to lacks a foundation, a base, although it, like PP, certainly has an interesting character.

Tristram

“Shout with the loudest.” Seems like such advice is still followed today. Perhaps the only slight alteration would be “try to be the loudest shouter.” Civility seems to be lost in too many discussions today.

You ask if the action is moving too slowly or if the novel is too episodic. I am asking myself that as well. When we were reading Sketches By Boz we knew we were reading individual stories. Thus, each story was in itself, self-contained. I find that most of the chapters so far in PP could well stand on their own. I think to Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford. It too originally set out to be episodes of the widows in the town of Cranford. With a bit of fitting, those individual stories do blend into a novel of sorts.

With the coming of Sam Weller we have a glue point to which the narrative of Pickwick can find some stronger foundation. Still, since the activity and the mandate of the Pickwick Club seems to be to wander about, and both get into bits of trouble and adventure and then get out of them, we are lacking a foundation. Dickens did much with great skill, but perhaps what he did best was to create a sense of place in his later novels. London, of course, was his heart, but the marsh country of Pip and the cloistered town of The Mystery of Edwin Drood and other settings are deep and rich veins of blood that ground our reading. In PP we have, as yet, no base, no foundation, no central point around which to build a story.

My feeling is that we still have a picaresque novel. I agree with your observations on Gulliver’s Travels. The key word is “Travels.” It to lacks a foundation, a base, although it, like PP, certainly has an interesting character.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Curiosities,

In the instalment we are going to discuss this week, Mr Pickwick’s adventures seem to be taking a slightly different turn even though at first sight, ever..."

I'll take a note of the respective Wellerisms in the chapters I am going to summarize as well now, Peter, and I am sure we are going to end with an ample list.

In the instalment we are going to discuss this week, Mr Pickwick’s adventures seem to be taking a slightly different turn even though at first sight, ever..."

I'll take a note of the respective Wellerisms in the chapters I am going to summarize as well now, Peter, and I am sure we are going to end with an ample list.

As to the picaresque character of the novel, I have noticed that so far, every single instalment, with the exception of the first one, contains one short story that has been inserted into the main plot, and so maybe, we are in for another list, Peter - a list of short stories. So far we have:

1. The Story of the Dying Clown

2. The Convict's Return

3. The Madman's Tale

4. The Bagman's Tale

Let's see if Dickens is going to keep up that pattern, and maybe we can even spot recurring motifs in the stories.

1. The Story of the Dying Clown

2. The Convict's Return

3. The Madman's Tale

4. The Bagman's Tale

Let's see if Dickens is going to keep up that pattern, and maybe we can even spot recurring motifs in the stories.

Tristram wrote: "As to the picaresque character of the novel, I have noticed that so far, every single instalment, with the exception of the first one, contains one short story that has been inserted into the main ..."

Yes. It will be an interesting exploration.

Yes. It will be an interesting exploration.

I love the idea of a Wellerism hunt!

I love the idea of a Wellerism hunt!Tristram asked, "Do you think Sam Weller and his stories – here the one about his father, which is quite morbid, considering that one old gentleman never showed up again after the coach fell into the river – entertaining and enriching to the story?"

I'm not sure what it says about me, but among the moments of this book that are making me laugh the hardest are all the flippant gratuitous violence parts--Sam's dad crashing the coach, the mother in the first installment who can't eat because her head's been knocked off... I guess I shouldn't laugh but I DO. Partly these stories are so quick, so tangential, and so absurd that they don't feel real, and also there's this element of did he really just say that?

Anyway, after two stories I think I could get very attached to anecdotes about Sam's father, and I hope we get one for every installment.

I shan't participate in the Wellerism hunt. One of my best used reference books is "The Dickens Encyclopedia" by Arthur Hayward, and in the back of the book is a full list of all the Wellerism to be found in "Pickwick" (as well as "Wisdom From Mrs. Gamp"!). I see there are a couple of inexpensive used copies available online, for anyone who might like to add it to their libraries. I've found it to be very useful and thorough, and have appreciated having it (though the pages are printed on rather cheap paper, unfortunately).

I shan't participate in the Wellerism hunt. One of my best used reference books is "The Dickens Encyclopedia" by Arthur Hayward, and in the back of the book is a full list of all the Wellerism to be found in "Pickwick" (as well as "Wisdom From Mrs. Gamp"!). I see there are a couple of inexpensive used copies available online, for anyone who might like to add it to their libraries. I've found it to be very useful and thorough, and have appreciated having it (though the pages are printed on rather cheap paper, unfortunately).

Mrs. Bardell faints in Mr. Pickwick's arms

Chapter 12

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Bless my soul," cried the astonished Mr. Pickwick; "Mrs. Bardell, my good woman — dear me, what a situation — pray consider. — Mrs. Bardell, don't — if anybody should come —"

"Oh, let them come," exclaimed Mrs. Bardell frantically; "I’ll never leave you — dear, kind, good soul;" and, with these words, Mrs. Bardell clung the tighter.

"Mercy upon me," said Mr. Pickwick, struggling violently, "I hear somebody coming up the stairs. Don’t, don’t, there’s a good creature, don’t." But entreaty and remonstrance were alike unavailing; for Mrs. Bardell had fainted in Mr. Pickwick’s arms; and before he could gain time to deposit her on a chair, Master Bardell entered the room, ushering in Mr. Tupman, Mr. Winkle, and Mr. Snodgrass.

Mr. Pickwick was struck motionless and speechless. He stood with his lovely burden in his arms, gazing vacantly on the countenances of his friends, without the slightest attempt at recognition or explanation. They, in their turn, stared at him; and Master Bardell, in his turn, stared at everybody.

The astonishment of the Pickwickians was so absorbing, and the perplexity of Mr. Pickwick was so extreme, that they might have remained in exactly the same relative situations until the suspended animation of the lady was restored, had it not been for a most beautiful and touching expression of filial affection on the part of her youthful son. Clad in a tight suit of corduroy, spangled with brass buttons of a very considerable size, he at first stood at the door astounded and uncertain; but by degrees, the impression that his mother must have suffered some personal damage pervaded his partially developed mind, and considering Mr. Pickwick as the aggressor, he set up an appalling and semi-earthly kind of howling, and butting forward with his head, commenced assailing that immortal gentleman about the back and legs, with such blows and pinches as the strength of his arm, and the violence of his excitement, allowed.

"Take this little villain away," said the agonised Mr. Pickwick, "he's mad. "

"What is the matter?" said the three tongue-tied Pickwickians.

"I don’t know," replied Mr. Pickwick pettishly. "Take away the boy." (Here Mr. Winkle carried the interesting boy, screaming and struggling, to the farther end of the apartment.) ‘Now help me, lead this woman downstairs."

Commentary:

Things are sometimes not what they seem; and an auditor may apprehend an utterance in ways that the speaker would not expect. Certainly these reflections spring to the viewer's mind when he or she analyses the situation in the first of two Phiz illustrations for August 1836, "Mrs. Bardell faints in Mr. Pickwick's arms." A cynic might even suggest that the widow's "fainting" is mere a piece of stage business to cement for the witnesses who are about to appear the notion that her lodger has proposed marriage, instead of put a hypothetical question about the costs of keeping a servant — specifically, the "boots" at the White Hart, Sam Weller, for it is he to whom Pickwick is alluding when he mentions that one of the benefits of the arrangement will be a suitable "companion" (or, as we might say, "father figure") for young Tommy Bardell, as in Thomas Nast's 1873 woodcut, which captures the quiet moment prior to Mrs. Bardell's misconstruing Pickwick's question as a proposal of marriage:

"He, too, will have a companion," resumed Mr. Pickwick, "a lively one, who'll teach him, I'll be bound, more tricks in a week than he would ever learn in a year." And Mr. Pickwick smiled placidly.

"Oh, you dear —" said Mrs. Bardell.

The background in Phiz's revised version of this illustration, as Steig notes, includes telling details in the Hogarthian manner. The peculiar figure with his scythe above the clock on the mantelpiece must be Father Time (perhaps conveying the editorial that both Mr. Pickwick and the widow area little too old to be falling prey to the romantic passions). The ornately-framed neoclassical picture above the mantle also offers oblique commentary in that it involves Cupid's preparing to shoot an arrow at a bare-breasted woman (perhaps his mother, the goddess Venus), whose languorous pose provides a female figure far more alluring than Mrs. Bardell's. In a "sinking" effect, the equivalent figure to Cupid in the foreground is the vicious Tommy Bardell.

Since Phiz customarily executed more than one version of any 1836-37 steel plate to allow for the wear and tear of taking thousands of impressions, differences between different etchings are sometimes evident. Here, for example, Frederic G. Kitton notes:

the etching where Master Bardell is seen kicking Mr. Pickwick, the boy was first drawn with his head down, but was subsequently represented with it raised, the attitudes of Snodgrass and Winkle being also slightly changed. . . .

Michael Steig, who possessed complete sets of both earlier and later printings of these illustrations, reported considerable improvement in the second version:

Browne's 1836 and 1838 versions of his third illustration, "Mrs. Bardell faints in Mr. Pickwick's arms" (ch. 12), provide an especially interesting example of this talent and its development. In the 1836 plate, with its harsh and scarcely relieved verticals, the rendering of both room and characters is rudimentary and stiff. Considered abstractly, the overall composition adequately conveys the point of the scene — Mr. Pickwick at the center holds Mrs. Bardell, harried by Master Bardell on one side while scrutinized by his friends on the other. Most interesting, however, are the rather tentatively etched details above the door: a stuffed owl and the sculptured head of what appears to be an elderly man. Presumably these constitute some kind of ironic reference to wisdom and sagacity, or perhaps the head simply suggests Pickwick's rather advanced age.

In the redesigned plate for the 1838 edition not only has Browne enormously improved the rendering of characters and scene so that the illustration comes alive in contrast to the stiff, formal feeling of the earlier one, but he eliminates the two vaguely emblematic details and introduces three new, much clearer ones: a framed picture above the mirror, showing Cupid aiming an arrow at a languid nude; on the chimneypiece, a pair of vases with fresh flowers in them; and between these, an ornamental clock featuring Father Time with his scythe. The clock is immediately behind Pickwick's head, while the right-hand vase is behind Mrs. Bardell's, so that the clear implication is a lightly ironic commentary upon the conjunction of age and (relative) youth. [Steig 26-27]

If you see an owl or the head of an old man good for you, I need new glasses. I would say here's a bird for you Peter, but I don't see one.

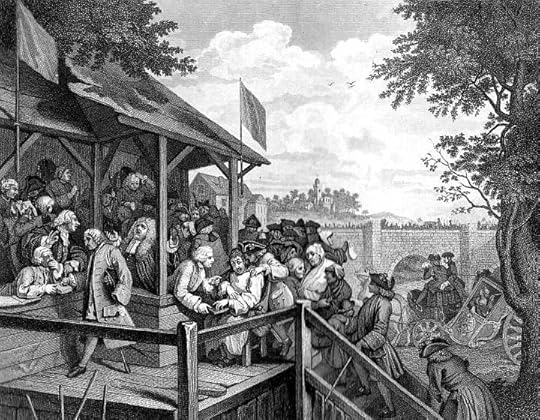

The Election at Eatanswill

Chapter 13

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Then Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, of Fizkin Lodge, near Eatanswill, presented himself for the purpose of addressing the electors; which he no sooner did, than the band employed by the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, commenced performing with a power to which their strength in the morning was a trifle; in return for which, the Buff crowd belaboured the heads and shoulders of the Blue crowd; on which the Blue crowd endeavoured to dispossess themselves of their very unpleasant neighbours the Buff crowd; and a scene of struggling, and pushing, and fighting, succeeded, to which we can no more do justice than the mayor could, although he issued imperative orders to twelve constables to seize the ringleaders, who might amount in number to two hundred and fifty, or thereabouts. At all these encounters, Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, of Fizkin Lodge, and his friends, waxed fierce and furious; until at last Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, of Fizkin Lodge, begged to ask his opponent, the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, of Slumkey Hall, whether that band played by his consent; which question the Honourable Samuel Slumkey declining to answer, Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, of Fizkin Lodge, shook his fist in the countenance of the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, of Slumkey Hall; upon which the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, his blood being up, defied Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, to mortal combat. At this violation of all known rules and precedents of order, the mayor commanded another fantasia on the bell, and declared that he would bring before himself, both Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, of Fizkin Lodge, and the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, of Slumkey Hall, and bind them over to keep the peace. Upon this terrific denunciation, the supporters of the two candidates interfered, and after the friends of each party had quarrelled in pairs, for three–quarters of an hour, Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, touched his hat to the Honourable Samuel Slumkey; the Honourable Samuel Slumkey touched his to Horatio Fizkin, Esquire; the band was stopped; the crowd were partially quieted; and Horatio Fizkin, Esquire, was permitted to proceed. I hate elections.

Commentary:

The second illustration for August 1836 involves a by-election somewhere in Essex — Bury St. Edmunds (near Norwich, mentioned at the opening of the chapter) has been nominated as the original of "Eatanswill," although as a young short-hand reporter Dickens had covered just such an election in 1834 at Sudbury (Collins and Guiliano 123). The patriotic Pickwick takes the side of Mr. Pott, editor of The Gazette and the Blues (Tories), whose candidate is the Honourable Samuel Slumkey — of whom Pickwick had not even heard until arriving that morning by coach. He takes as his governing principle in such matters "It's always best on these occasions to do what the mob do"; certainly, such a principle is the most expedient. Ironically, Dickens himself was a "Buff," that is, a Liberal adherent, and so he frames his protagonist as a supporter of the status quo and the opponent of social and electoral change, the issue in the great election of 1832 being extension of the franchise. Expediency, in terms of acquiring rooms for the night, prompts Pickwick to announce himself as an adherent of Slumkey, whose agent is none other than the lawyer Perker whom he had met at the White Hart.

In the illustration, we find Mr. Pickwick easily (flanked by Winkle and Snodgrass, right), but struggle to identify Mr. Pott ("a tall, thin man, with a sandy-colored head inclined to baldness . . . dressed in a long brown surtout, with a black cloth waistcoat, and drab trousers"), a distinguished member of the fourth estate carrying a double eye-glass. The only logical figure is the balding man in the lighter coat to the left of Pickwick.

The whole scene is reminiscent of The Election (Part 3. "The Polling," and Part 4. "Chairing the Member") by William Hogarth, from whom Phiz often drew inspiration. In a hundred years, British parliamentary democracy has only inched forward, so that, according to Dickens and Phiz, an election is still characterized by empty rhetoric and conflicting mobs supporting the Buffs (Whigs) and Blues (Tories); however, the absolute veniality and violence that one sees in Hogarth's series is absent in Phiz's "Election at Eatanswill." The scene in each, however, is equally chaotic. A typical Phizzian touch is the presence of conflicting placards that proclaim, on the one hand, "Slumkey and Principle!" but on the other announce "For Slumkey read Donkey." One ruffian brandishes his placard (bearing the notation "Down with Slumkey") as a weapon, poking one of Slumkey's supporters in the stomach (left), and three other Slumkey supporters lie on the ground, the one in the center attempting to recover his tankard. Thus, while a certain measure of discipline exists above, on the hustings, the scene below is a melee of conflicting signs, cacophonous discord (note the trombone-player and drummer as representatives of Slumkey's band), and mayhem. Phiz's illustration thus captures the essence of Dickens's parallel present participles, ""struggling, and pushing, and fighting" among a crowd difficult to calculate in number (Dickens gives the figure 250, but clearly there are not that many conflicting adherents in the plate). Above, the mayor (extreme left) gives commands and the rotund town crier rings his bell, but significantly Phiz depicts not one of the twelve constables whom the mayor has ordered to seize the ringleaders. The candidates themselves, Slumkey and Fizkin, must be two of the three figures between Pickwick (right) and the crier (center). The exercise of the democratic franchise seems in Phiz's illustration to be a mere pretense for an outburst of mindless mob violence.

The Election

William Hogarth

he too, will have a companion,’

Chapter 12

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘You’ll think it very strange now,’ said the amiable Mr. Pickwick, with a good-humoured glance at his companion, ‘that I never consulted you about this matter, and never even mentioned it, till I sent your little boy out this morning—eh?’

Mrs. Bardell could only reply by a look. She had long worshipped Mr. Pickwick at a distance, but here she was, all at once, raised to a pinnacle to which her wildest and most extravagant hopes had never dared to aspire. Mr. Pickwick was going to propose—a deliberate plan, too—sent her little boy to the Borough, to get him out of the way—how thoughtful—how considerate!

‘Well,’ said Mr. Pickwick, ‘what do you think?’

‘Oh, Mr. Pickwick,’ said Mrs. Bardell, trembling with agitation, ‘you’re very kind, sir.’

‘It’ll save you a good deal of trouble, won’t it?’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Oh, I never thought anything of the trouble, sir,’ replied Mrs. Bardell; ‘and, of course, I should take more trouble to please you then, than ever; but it is so kind of you, Mr. Pickwick, to have so much consideration for my loneliness.’

‘Ah, to be sure,’ said Mr. Pickwick; ‘I never thought of that. When I am in town, you’ll always have somebody to sit with you. To be sure, so you will.’

‘I am sure I ought to be a very happy woman,’ said Mrs. Bardell.

‘And your little boy—’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Bless his heart!’ interposed Mrs. Bardell, with a maternal sob.

‘He, too, will have a companion,’ resumed Mr. Pickwick, ‘a lively one, who’ll teach him, I’ll be bound, more tricks in a week than he would ever learn in a year.’ And Mr. Pickwick smiled placidly.

‘Oh, you dear—’ said Mrs. Bardell.

Mr. Pickwick started.

‘Oh, you kind, good, playful dear,’ said Mrs. Bardell; and without more ado, she rose from her chair, and flung her arms round Mr. Pickwick’s neck, with a cataract of tears and a chorus of sobs.

Take this little villain away, said the agonised Mr. Pickwick.

Chapter 12

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

In the Household Edition's version of this scene ("'Take this little villain away,' said the agonized Mr. Pickwick,"), one might expect further emblematic development. In fact, in revising in the more realistic style of the sixties, Phiz has emphasized the theatrical over the emblematic, eliminating background details that parenthetically comment upon Pickwick's situation. Nast's American Household Edition version is even more barren, including as it does no background elements, nor even the audience of Pickwickians; in fact, there is nothing apparently dramatic about Nast's scene since an elderly Mrs. Bardell and equally elderly Mr. Pickwick are not realized in a compromising situation, but are talking rationally about "a companion" for Master Bardell.

The 1873 versions of this scene have almost no such tantalizing Hogarthian details in the background (the exception being the desiccated plant in the vase, right, which would seem to be a comment on the nature of the "lovers"). Phiz's focus in his Household Edition woodcut is solely on the foregrounded action, which fills the horizontal frame: the smirking friends, among whom Tupman alone seems solicitous of Mrs. Bardell's condition; and Pickwick, trying to prevent Martha Bardell from falling, even as her ten-year-old, Tommy, tries to throw Pickwick himself off balance by kicking his shins and tugging at his coat-tail. Although the later illustration is decidedly inferior in its lack of emblematic detail and its failure to convey as sharply the reactions of the three comic Pickwickians to the spectacle of the fainting widow, the Household Edition woodcut has the virtue of making Mrs. Bardell more comely — and of making Master Tommy, with his wild hair, more of an individual than a type. The three friends (well individualized in face and form) enter from the right in the 1836 illustration, but from the usual direction for stage entrances (the left; i. e., stage right) in the Household Edition woodcut, which in its solidity, grouping of figures, and minimizing of the properties in the background seems more of a theatrical moment or tableau vivant. The continuity between the two illustrations lies — despite the shifting of the observers from right to left — in the costuming, juxtapositions, and postures of the six characters: in particular, we note Tupman's girth, Pickwick's rotund figure and obvious dismay, Mrs. Bardell's hat and apron, and Mr. Winkle's gaiters. The two illustrations are also not inconsistent in the artist's use of a blank mirror above the mantelpiece to imply a lack of perception or clarity of apprehension, for Pickwick often fails to see himself as others see him; in the 1873 illustration, the heads of Mr. Pickwick and Mrs. Bardell are so positioned that the viewer cannot see whether the Father Time clock is still present, and the top register of the 1873 coincides with the top of the mirror, so that one cannot see the ornately-framed (and ironically themed) neoclassical picture of the triumph of erotic desire.

Mrs. Pott and Mr. Winkle

Chapter 13

William Heath

Pickwickian Illustrations

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘You see, Mr. Pickwick,’ said the host in explanation of his wife’s lament, ‘that we are in some measure cut off from many enjoyments and pleasures of which we might otherwise partake. My public station, as editor of the Eatanswill Gazette, the position which that paper holds in the country, my constant immersion in the vortex of politics—’

‘P. my dear—’ interposed Mrs. Pott.

‘My life—’ said the editor.

‘I wish, my dear, you would endeavour to find some topic of conversation in which these gentlemen might take some rational interest.’

‘But, my love,’ said Mr. Pott, with great humility, ‘Mr. Pickwick does take an interest in it.’

‘It’s well for him if he can,’ said Mrs. Pott emphatically; ‘I am wearied out of my life with your politics, and quarrels with the Independent, and nonsense. I am quite astonished, P., at your making such an exhibition of your absurdity.’

‘But, my dear—’ said Mr. Pott.

‘Oh, nonsense, don’t talk to me,’ said Mrs. Pott. ‘Do you play ecarte, Sir?’

‘I shall be very happy to learn under your tuition,’ replied Mr. Winkle.

‘Well, then, draw that little table into this window, and let me get out of hearing of those prosy politics.’

The Election

Chapter 13

Racy Sketches of Expeditions from the Pickwick Club

Thomas Sibson

1838

Text Illustrated:

How or by what means it became mixed up with the other procession, and how it was ever extricated from the confusion consequent thereupon, is more than we can undertake to describe, inasmuch as Mr. Pickwick’s hat was knocked over his eyes, nose, and mouth, by one poke of a Buff flag-staff, very early in the proceedings. He describes himself as being surrounded on every side, when he could catch a glimpse of the scene, by angry and ferocious countenances, by a vast cloud of dust, and by a dense crowd of combatants. He represents himself as being forced from the carriage by some unseen power, and being personally engaged in a pugilistic encounter; but with whom, or how, or why, he is wholly unable to state. He then felt himself forced up some wooden steps by the persons from behind; and on removing his hat, found himself surrounded by his friends, in the very front of the left hand side of the hustings. The right was reserved for the Buff party, and the centre for the mayor and his officers; one of whom—the fat crier of Eatanswill—was ringing an enormous bell, by way of commanding silence, while Mr. Horatio Fizkin, and the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, with their hands upon their hearts, were bowing with the utmost affability to the troubled sea of heads that inundated the open space in front; and from whence arose a storm of groans, and shouts, and yells, and hootings, that would have done honour to an earthquake.

He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as their position did not enable them to see what was going forward.

Chapter 13

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Although the nature of elections in support of British parliamentary democracy must have become somewhat less adversarial, corrupt, and raucous between 1834 (the date of the Sudbury by-election covered by young reporter Charles Dickens) and the 1870s, Phiz merely reprised the 1836 engraving"The Election at Eatanswill" (Part 5: August 1836) for his 1873 woodcut for the British Household Edition. However, instead of celebrating the Hogarthian mob-mentality of the contest between the Buffs (Whigs) and Blues (Tories), Phiz like his American counterpart, Thomas Nast, chose to focus instead on the candidates' patting children on their heads and kissing babies to win their mothers' goodwill and their fathers' votes in "He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as to their position did not enable them to see what was going forward. and "He's kissing 'em all!" respectively. Whereas Phiz's Slumkey seems to have some tender regard for the infant he is about to kiss (centre), Nast's great-coated politician holds aloft a frightened toddler. The comparable juxtaposition of the candidates, the crowd — more raucous in the American version, more benign in the British — as a backdrop, and in particular an almost identical positioning of the sign "Slumkey for ever" (left rear) suggests that one artist was copying the other's work. The instigator of this electoral strategy for Samuel Slumkey is none other than than attorney Perker, who had negotiated earlier with Jingle at the White Hart in the Borough (Southwark) on behalf of Mr. Wardle. We may assume that, since neither Pickwick nor his comrades appear in either illustration, the perspective from which we see each scene is theirs:

‘Nothing has been left undone, my dear sir — nothing whatever. There are twenty washed men at the street door for you to shake hands with; and six children in arms that you’re to pat on the head, and inquire the age of; be particular about the children, my dear sir — it has always a great effect, that sort of thing."

"I’ll take care," said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

"And, perhaps, my dear Sir," said the cautious little man, "perhaps if you could — I don’t mean to say it’s indispensable — but if you could manage to kiss one of 'em, it would produce a very great impression on the crowd."

"Wouldn't it have as good an effect if the proposer or seconder did that?" said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

"Why, I am afraid it wouldn't," replied the agent; "if it were done by yourself, my dear Sir, I think it would make you very popular."

"Very well," said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, with a resigned air, "then it must be done. That's all."

"Arrange the procession," cried the twenty committee-men.

Amidst the cheers of the assembled throng, the band, and the constables, and the committee-men, and the voters, and the horsemen, and the carriages, took their places — each of the two-horse vehicles being closely packed with as many gentlemen as could manage to stand upright in it; and that assigned to Mr. Perker, containing Mr. Pickwick, Mr. Tupman, Mr. Snodgrass, and about half a dozen of the committee besides.

There was a moment of awful suspense as the procession waited for the Honourable Samuel Slumkey to step into his carriage. Suddenly the crowd set up a great cheering.

"He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as their position did not enable them to see what was going forward.

Another cheer, much louder.

"He has shaken hands with the men," cried the little agent.

Another cheer, far more vehement.

"He has patted the babies on the head," said Mr. Perker, trembling with anxiety.

A roar of applause that rent the air.

"He has kissed one of 'em!" exclaimed the delighted little man.

A second roar.

"He has kissed another," gasped the excited manager.

A third roar.

"He's kissing 'em all!’" screamed the enthusiastic little gentleman, and hailed by the deafening shouts of the multitude, the procession moved on. [chapter 13 Harper & Brothers' edition]

Apparently a politician's kissing babies was then not quite so great a cliché. The massive presence of young women, none of whom could vote even in the 1870s, at first glance would seem an anomaly to a modern reader; however, as Perker has explained to Pickwick earlier in the election chapter, the way to securing the votes of the male electors lay through their wives and children — indeed, the Honourable Slumkey's re-election committee has already bribed forty-five women with green parasols. Now Slumkey must the ultimate political gesture: kiss every baby presented to him. And Phiz has given us seven infants, four young children, and eleven young women, whereas the adult males in the crowd near the Town Arms (for which Nast has incorporated the sign in his design) number a mere nine, exclusive of the child-patting candidate (center) himself. Processional signs in both Household Edition illustrations proclaim, "Slumkey forever," although Phiz's sign is missing the "for" (upper left) and the name "Slumkey" has been divided, with humorous effect. The shaggy hairstyles, disreputable hats, smock-frocks and aprons of "bully-boy" Slumkey adherents (left) in Nast's illustration together with the prominence of the sign "Town Arms" in the background (left) recalls the suborned bar-maid's spiking with laudanum the brandy-and-water of fourteen un-polled electors in the previous Eatanswill election, an anecdote that Sam Weller recounted to Pickwick before breakfast that day.

Although Phiz sided with young Dickens, who was very much a Radical in the early 1830s, supporting the Great Reform Bill of Lord John Russell in 1832, Nast was a virulent opponent of governmental corruption, the New York Democratic party machine, and the Tammany Hall political clique, as well as an anti-slavery proponent (and therefore a staunch Republican). Consequently, both Household Edition illustrations take a dim view of traditional political shenanigans and "dirty tricks."

Julie wrote: "I love the idea of a Wellerism hunt!

Tristram asked, "Do you think Sam Weller and his stories – here the one about his father, which is quite morbid, considering that one old gentleman never showe..."

Hi Julie

Let’s make it official. The great Wellerism Hunt is on. If we miss any, hopefully Amy Lou will point it out.

As for Mr Weller senior ... I think like a good opera, it will take a long time, hopefully never, for him to pass from the pages of PP.

Tristram asked, "Do you think Sam Weller and his stories – here the one about his father, which is quite morbid, considering that one old gentleman never showe..."

Hi Julie

Let’s make it official. The great Wellerism Hunt is on. If we miss any, hopefully Amy Lou will point it out.

As for Mr Weller senior ... I think like a good opera, it will take a long time, hopefully never, for him to pass from the pages of PP.

"He's Kissing 'Em All!"

Chapter 13

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"He has patted the babies on the head," said Mr. Perker, trembling with anxiety.

A roar of applause that rent the air.

"He has kissed one of 'em!" exclaimed the delighted little man.

A second roar.

"He has kissed another," gasped the excited manager.

A third roar.

"He's kissing 'em all!’" screamed the enthusiastic little gentleman, and hailed by the deafening shouts of the multitude, the procession moved on. [chapter 13 Harper & Brothers' edition]

What the Devil are You Winking At Me For?

Chapter 14

William Heath

Pickwickian Illustrations

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘In about half an hour, Tom woke up with a start, from a confused dream of tall men and tumblers of punch; and the first object that presented itself to his waking imagination was the queer chair.

‘“I won’t look at it any more,” said Tom to himself, and he squeezed his eyelids together, and tried to persuade himself he was going to sleep again. No use; nothing but queer chairs danced before his eyes, kicking up their legs, jumping over each other’s backs, and playing all kinds of antics.

“‘I may as well see one real chair, as two or three complete sets of false ones,” said Tom, bringing out his head from under the bedclothes. There it was, plainly discernible by the light of the fire, looking as provoking as ever.

‘Tom gazed at the chair; and, suddenly as he looked at it, a most extraordinary change seemed to come over it. The carving of the back gradually assumed the lineaments and expression of an old, shrivelled human face; the damask cushion became an antique, flapped waistcoat; the round knobs grew into a couple of feet, encased in red cloth slippers; and the whole chair looked like a very ugly old man, of the previous century, with his arms akimbo. Tom sat up in bed, and rubbed his eyes to dispel the illusion. No. The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart.

‘Tom was naturally a headlong, careless sort of dog, and he had had five tumblers of hot punch into the bargain; so, although he was a little startled at first, he began to grow rather indignant when he saw the old gentleman winking and leering at him with such an impudent air. At length he resolved that he wouldn’t stand it; and as the old face still kept winking away as fast as ever, Tom said, in a very angry tone—

‘“What the devil are you winking at me for?”

‘“Because I like it, Tom Smart,” said the chair; or the old gentleman, whichever you like to call him. He stopped winking though, when Tom spoke, and began grinning like a superannuated monkey.

Tom! Said the Old Gentleman, 'The Widow's a Fine Woman - Remarkably Fine Woman - Eh, Tom?'

Chapter 14

The Pickwick Illustrations

T. Onwhyn and Sam Weller

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘“Tom,” said the old gentleman, “the widow’s a fine woman—remarkably fine woman—eh, Tom?” Here the old fellow screwed up his eyes, cocked up one of his wasted little legs, and looked altogether so unpleasantly amorous, that Tom was quite disgusted with the levity of his behaviour—at his time of life, too!

‘“I am her guardian, Tom,” said the old gentleman.

‘“Are you?” inquired Tom Smart.

‘“I knew her mother, Tom,” said the old fellow: “and her grandmother. She was very fond of me—made me this waistcoat, Tom.”

‘“Did she?” said Tom Smart.

‘“And these shoes,” said the old fellow, lifting up one of the red cloth mufflers; “but don’t mention it, Tom. I shouldn’t like to have it known that she was so much attached to me. It might occasion some unpleasantness in the family.” When the old rascal said this, he looked so extremely impertinent, that, as Tom Smart afterwards declared, he could have sat upon him without remorse.

‘“I have been a great favourite among the women in my time, Tom,” said the profligate old debauchee; “hundreds of fine women have sat in my lap for hours together. What do you think of that, you dog, eh!” The old gentleman was proceeding to recount some other exploits of his youth, when he was seized with such a violent fit of creaking that he was unable to proceed.

‘“Just serves you right, old boy,” thought Tom Smart; but he didn’t say anything.

The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart

Chapter 14

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

With a greater number of illustrations than the 1838 original volume, the Household Edition on both sides of the Atlantic presented the illustrators of The Pickwick Papers with the opportunity to provide realizations of moments in the interpolated tales. In the case of the short story that Dickens wrote and published in 1836, the fourth interpolated tale of the novel, "The Bagman's Story" of travelling salesman Tom Smart and the talkative chair, both Hablot Knight Browne and Thomas Nast provided woodcuts in which the dreamer in his nightgown and nightcap, sitting up and apparently wide awake (despite the effects of half-a-dozen tumblers of punch after a ride through wind and rain) in an old inn on the Marlborough Downs converses with the elderly chair in his bedroom. The secret that the old chair imparts enables Tom to eliminate his rival for the hand of a wealthy, attractive widow who is the inn's kindly landlady.

What the improbable tale of the supernatural (told by the one-eyed bagman or travelling salesman in the commercial travellers' room at the Peacock Inn in Eatanswill) lacks in power and artistry it makes up for in the charm of description, enforcing the momentary reader's belief through highly specific descriptions of Tom Smart's gig, spirited mare, and dreary journey across the downs in a driving storm. Part of the anticipatory set which makes the story enjoyable is that, at its opening, the reader already knows the protagonist will encounter a talking chair because of the presence of an informative illustration — "The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart" by Phiz for British readers, and "A most extraordinary change seemed to come over it" by Nast for Americans. Thus, the Household Edition reader is prepared for the miraculous transformation in advance of encountering the scene in the text; in the American Household Edition, although the illustration occurs on the same page as the text, the reader processes the illustration prior to reading the passage, even if he or she can resist the overwhelming temptation to see what illustrations will occur within the chapter before he or she actually begins to read it. The behaviour and attitude of the talking chair enable the reader to suspend disbelief long enough to enjoy the poetic justice of the would-be bigamist's being discredited by the letter he has foolishly left in his trouser-pocket for Tom to discover — with the aid of the old chair — and deploy against him. Although both Nast and Phiz have elected to realise the same scene, there are some differences in their treatment, as Phiz makes the remarkable chair the centre of his picture, while Nast has chosen to focus on the protagonist instead by giving him greater prominence and showing him unobscured by bed curtains. The artists have also realised the magical chair with differing degrees of success, for Nast's chair is almost entirely an old man of eighteenth-century vintage (the setting being approximately 1750), while Phiz's is merely a chair with a face that renders Tom curious rather than, as in Nast's illustration, startled. Examining the passage and comparing its descriptions of the chair, the reader with both illustrations before him may decide which more effectively realises Dickens's amusing and imaginative description of the "fairy godfather" figure:

"Tom gazed at the chair; and, suddenly as he looked at it, a most extraordinary change seemed to come over it. The carving of the back gradually assumed the lineaments and expression of an old, shrivelled human face; the damask cushion became an antique, flapped waistcoat; the round knobs grew into a couple of feet, encased in red cloth slippers; and the whole chair looked like a very ugly old man, of the previous century, with his arms akimbo. Tom sat up in bed, and rubbed his eyes to dispel the illusion. No. The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart.

In Phiz's version, light from the fireplace (left) plays across the room, highlighting Tom, sitting up in the four-poster, and leaving in partial darkness the chair with a face and the dresser (the "oaken press" that figures prominently in the hidden letter plot) with decorative goblins on either side that imply the object's numinous power. The chair, occupying the centre of the composition, looks towards the right register but is separated from Tom by the bed curtains, which take up an inordinate amount of space. In Nast's version, the orientation of the picture is completely reversed, with the dreamer on the left, and the chair on the right: Tom Smart, looking towards the right, occupies the centre of the composition, with a large stuffed chair to the left balancing the transformed chair to the right. On the whole, Nast seems not to have concerned himself with the fireplace as the available light source as the entire composition is well-lit (implying, perhaps, that the fireplace is in the "fourth wall," i. e., the viewer's position). Although Nast's figures are better modelled, his Tom is not the beguiled and attractive youth of Phiz's plate, but rather a middle-aged, slightly overweight bachelor sporting bushy sideburns. Despite the fact that Phiz's illustration lacks the intricate detailing of his earlier style, the British Household Edition plate is more successful (through Tom's expression and the oaken press) at communicating the tall tale's sense of the wondrous which Dickens termed "Fancy."

A Most Extraordinary Change Seemed To Come Over It

Chapter 14

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Tom Smart and the Chair

Chapter 14

Original design for The Pickwick Papers

John Leech (age of 19)

Pencil drawing, faintly tinted in colors, as a specimen of the artist's work, submitted to the publishers early in the progress of the first issue in monthly parts.

Commentary:

After the lamented death of Robert Seymour, it has been seen that the author and publishers of the Pickwick Papers were placed in the difficult position of having to discover an artist qualified to take the place of that admirable designer, who was, in so considerable a degree, concerned in the original appearance of the Pickwick Club. Mr. John Jackson, the eminent wood-engraver ( a personage of practical influence in the arts), who was working at the time for Chapman and Hall, and had engraved on wood the Seymour design for the wrapper now historical, recommended R. W. Buss, whose drawings on wood he was engraving for "The Library of Fiction," another venture of Messrs.

Hablot Knight Brown, then a youth of twenty, and W. M. Thackeray - then at the age of twenty-five, who was already a more experienced hand - had offered their artistic assistance; but the gifted and versatile "Phiz," with marked success, had been commissioned to continue the traditions of Seymour.

About the same time John Leech, still younger, had also entered the field. He, too, though but eighteen at the time, had in 1835 made a juvenile attempt at publication in "The Etchings and Sketchings, by A. Pen, Esq." More consideration was given to his application than was afforded to the sketches submitted by Thackeray, for to Leech was proposed a subject for illustration, Part V, "Tom Smart and the Chair," and he accordingly sent in a pencil drawing tinted in water-colors, which remained in the possession of the publishers. By that date Phiz had been given the job and had been assured by the success of his plates for Part IV already published.

The incident of "Tom Smart and the Chair" was never illustrated in the original sense for Phiz was already carrying the work on with spirit, and Leech was not commissioned to etch his design. The water-color indicated promise, but that gifted artist was then a mere beginner, and his art at that date obviously crude, inexperienced and undeveloped.

John Leech and Charles Dickens were destined to become such close and affectionate friends in the future, it is a source of surprise, and speaks volumes for the high estimation in which was held Dickens's long-established artistic colleague and coadjutor "Phiz," that it was not until the appearance of Dickens's Christmas Book, the immortal "Christmas Carol", in 1843, that these staunch and attached friends - Dickens and Leech - in their respective walks the most popular artists that have ever delighted the British public, had the desirable advantage of appearing in collaboration.

The universal success of the little "Christmas Carol," probably unique alike in the annals of literature and of illustrative art, must have consoled the sensitive John Leech for the unfavorable reception his immature design for the "Pickwick Papers" had encountered in being "shelved" seven years previously, when his artistic future lay unexplored and, in those juvenile days, unsuspected.

Kim, you may know that already, but I'll say it anyway: You are a treasure, and your quest for illustration is a great enrichment to how I enjoy reading this novel. William Heath's idea of the old chair dimly reminds me of Humpty-Dumpty. With regard to the mysterious chair, I cannot help thinking that it was very wise in Phiz (and Dickens) to have refrained from visualizing the Tom Smart episode. I don't know what the other Curiosities think but I feel slightly disappointed by the illustrations in this chapter because the whole scene is so quaint and unusual that every reader will probably have their own mental picture of the awe-inspiring chair and to find it represented as a kind of Humpty-Dumpty is, to say the least, a sobering experience. In some situations, it is best to trust to the individual's imagination - a rule that director Jacques Tourneur respected in many of his horror films - and to refrain from showing a supernatural being too explicitly. The best painter, after all, is the human mind. ;-)

Tristram wrote: "The best painter, after all, is the human mind."

Tristram wrote: "The best painter, after all, is the human mind."I agree with this, Tristram. And once one sees someone else's interpretation on paper (or screen, as the case may be), it's nearly impossible to go back and see one's own mental image. Does anyone read Gone With the Wind without picturing Vivien Leigh as Scarlet O'Hara, or Harry Potter without seeing Daniel Radcliffe? I wish had some artistic talent so I could put my own visions on paper before they morphed into the visions of others.

Having said that, my gray matter stops at a vague idea of a character's features, but rarely fills in the detail that many of Dickens' artists give us, with the crowds, the paintings on the wall, the birds (none this week, that I could find!)... I greatly appreciate that they delve into the details of the scene. Especially with the 19th century wardrobes -- without artists' depictions, I think I'd imagine everyone in jeans and t-shirts. :-)

Thank you, Kim, as always, for sharing these with us!

Tristram wrote:

Tristram wrote:" I cannot help thinking that it was very wise in Phiz (and Dickens) to have refrained from visualizing the Tom Smart episode. I don't know what the other Curiosities think but I feel slightly disappointed by the illustrations in this chapter because..."

I agree. I am so glad none of those illustrations appeared in my Penguin copy of PP. As I was scrolling through them, I kept thinking that each one fell short somehow. The Tom Smart story wasn't nearly as dramatic as previous ones, but it was surprisingly engaging, and vaguely unsettling ... (the chair reminded me of a dirty old man for some reason). Anyway, I'm glad the whole thing played out in my imagination before I saw these illustrations.

Peter wrote: "Let’s make it official. The great Wellerism Hunt is on. If we miss any, hopefully Amy Lou will point it out..."

Peter wrote: "Let’s make it official. The great Wellerism Hunt is on. If we miss any, hopefully Amy Lou will point it out..."Peter, I also love the idea of a Wellerism hunt! Count me in!

Tristram wrote: "...All in all, I really enjoyed this satirical glimpse into policy a lot. What do you think about it?..."

Tristram wrote: "...All in all, I really enjoyed this satirical glimpse into policy a lot. What do you think about it?..."I loved chapter 13. The band playing to prevent the candidate of the other party from speaking, reminds me of some devastating revelations concerning some politicians that come just before some election, like for instance: he was fined for illegally parked car, and he hasn’t paid the fine yet; or the awful discovery of a picture of him at the nude beach when he was young. Sometimes they sound just like Eatanswill’s band playing.

Tristram wrote: "...The Bagman’s Story itself is completely different in tone from any of the stories we have got so far – light-hearted, quaint and not taking itself too seriously..."

Tristram wrote: "...The Bagman’s Story itself is completely different in tone from any of the stories we have got so far – light-hearted, quaint and not taking itself too seriously..."After the gloomy story of the Convict’s Return, I appreciated this light-hearted story. Tom Smart appears to be a colleague of Mr. Jingle: he wins the mature woman’s heart for her money, stealing her from another suitor. And he’s got an excellent teacher helping him: a Casanova-chair which is irresistibly enjoyable. His behaviour is so libertine that even the smart Tom Smart is disgusted. I loved this part:

Here the old fellow screwed up his eyes, cocked up one of his wasted little legs, and looked altogether so unpleasantly amorous, that Tom was quite disgusted with the levity of his behaviour.

Speaking about imagination, the scene I imagined really made me laugh.

Mary Lou wrote: "Especially with the 19th century wardrobes -- without artists' depictions, I think I'd imagine everyone in jeans and t-shirts. :-)"

My mental eye clothes every Victorian gentleman in a deerstalker and a cape, and the ladies in crinoline. And this happens, although I read quite a lot about 19th century everyday culture, esp. in Germany and Victorian England and should know that even in Holmes's day and age, this was not the usual thing to wear, the deerstalker and cape, I mean. Was it not in Billy Wilder's "The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes" that the sleuth complained about having to wear this kind of attire simply because his illustrator always depicted him as doing so? - Jeremy Brett, for instance, only wears cape and deerstalker in the countryside, and never in the metropolis.