Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses discussion

The Metamorphoses - The 15 Books

>

Book Three - 10th December, 2018

message 1:

by

Kalliope

(new)

Sep 22, 2018 06:39AM

Discussion of Third Book.

Discussion of Third Book.

reply

|

flag

ACTAEON OPERA. Early on in Book III comes the story of Diana and Actaeon. This has special interest for me because I have done two productions of Actéon, the opera-pastorale written around 1680 by Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704). There are several recordings on YouTube, but video gives slimmer pickings. However, take a look at this one from a performance at Versailles under Christophe Rousset. The link starts you in the middle of the scene with Diana's nymphs, which contains the most delectable music in the opera. After a duet and an aria, you will get the encounter of Actaeon and Diana, followed by his transformation into a stag.

ACTAEON OPERA. Early on in Book III comes the story of Diana and Actaeon. This has special interest for me because I have done two productions of Actéon, the opera-pastorale written around 1680 by Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704). There are several recordings on YouTube, but video gives slimmer pickings. However, take a look at this one from a performance at Versailles under Christophe Rousset. The link starts you in the middle of the scene with Diana's nymphs, which contains the most delectable music in the opera. After a duet and an aria, you will get the encounter of Actaeon and Diana, followed by his transformation into a stag.Despite performing at Versailles, this is a modern production in rather low lighting. I hold no brief for the costuming of Actaeon, while those for the Nymphs frankly baffles me: why wear costumes at all, if they are going to reveal every bit of their bodies? And why put them in a metal mesh cage? I did just fine with all my singers in view and fully clothed; the music has sensuality aplenty! R.

TITIAN. Continuing with the Actaeon story, here is the pair of great Titian paintings of the subject. The first, of Actaeon spying on Diana, was finished aroung 1559, and is now in the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. The sequel, of Actaeon as a stag being pursued by his hounds and shot apparently by Diana (this bit not taken from Ovid), was started around the same time, but left unfinished. It is now in the National Gallery in London. R.

TITIAN. Continuing with the Actaeon story, here is the pair of great Titian paintings of the subject. The first, of Actaeon spying on Diana, was finished aroung 1559, and is now in the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. The sequel, of Actaeon as a stag being pursued by his hounds and shot apparently by Diana (this bit not taken from Ovid), was started around the same time, but left unfinished. It is now in the National Gallery in London. R.

SCULPTURE. Here is the Actaeon myth turned to sculpture by Paolo Persico, Angelo Maria Brunelli, and Tommaso Solari in the park of the Royal Palace at Caserta, Italy, in the last quarter of the 18th century. As the first picture shows, the artists tell the story in two groups, roughly comparable to the two Titian pictures, though reading right to left. Diana and her nymphs are in the foreground (i.e. on the right), with a couple of the women dipping a toe into the water. In the background (left) is the group of Actaeon being attacked by his hounds; I have added a close-up to show the marvelous detail. R.

SCULPTURE. Here is the Actaeon myth turned to sculpture by Paolo Persico, Angelo Maria Brunelli, and Tommaso Solari in the park of the Royal Palace at Caserta, Italy, in the last quarter of the 18th century. As the first picture shows, the artists tell the story in two groups, roughly comparable to the two Titian pictures, though reading right to left. Diana and her nymphs are in the foreground (i.e. on the right), with a couple of the women dipping a toe into the water. In the background (left) is the group of Actaeon being attacked by his hounds; I have added a close-up to show the marvelous detail. R.

Great art, Roger - thanks.

Great art, Roger - thanks.Cadmus slaying the serpent and sowing its teeth to create warriors who then seem to slay themselves in quite a self-destructive manner until only five of them are left brought to mind the scene in the film Jason and the Argonauts in which the bad guy takes the teeth of a dragon Jason has slain, strews them on the ground, and thus creates a new army of skeleton warriors – the children of Hydra, with whom Jason has to contend. An amazing achievement of non-CG stop-motion animation by Ray Harryhausen, the designer of this scene, one of many in a rich effects-driven (and supposedly partially Ovid-influenced) film from 1963.

The transformation of Actaeon into a stag by the vengeful Diana whom he had discovered naked through no fault of his own (‘so were the fates directing him’), is a truly sublime scene, with his friends calling for him to join in the kill as they are unaware that is their friend himself whose demise they are witnessing. But why, oh why, did Ovid have to go to the extent of naming thirty-five different dogs who participated in this hunt? (And that blissfully only before he throws off the phrase ‘and others too numerous to name’). This scene, more than any other is the one in which my impression of Ovid was seriously diminished, and he became more of a show-off and less of an artist. More of a remnant of the oral-tradition, genealogy-minded bard and less of an interpreter of life’s mysteries in the guise of a true poet or dramatist.

What are we to make of Acteon, his character, his instincts? Despite the obvious overkill of Diana’s curse upon him, it’s perhaps difficult to sympathize greatly with the fellow: A rich, spoiled, idle sportsman, along with his crew and his vast pack of dogs, he hunts down and slaughters every beast they can find until they tire of the carnage. He suffers the misfortune of having not just one but two goddesses seeking vengeance upon him. He’s of the Theban clan, the great-nephew of the young woman who brought disgrace upon Juno. He compounds that fault by stumbling upon Diana at her bath. Is he a clumsy oaf or just unlucky?

What are we to make of Acteon, his character, his instincts? Despite the obvious overkill of Diana’s curse upon him, it’s perhaps difficult to sympathize greatly with the fellow: A rich, spoiled, idle sportsman, along with his crew and his vast pack of dogs, he hunts down and slaughters every beast they can find until they tire of the carnage. He suffers the misfortune of having not just one but two goddesses seeking vengeance upon him. He’s of the Theban clan, the great-nephew of the young woman who brought disgrace upon Juno. He compounds that fault by stumbling upon Diana at her bath. Is he a clumsy oaf or just unlucky?It’s not at all clear that Juno directly influenced Acteon’s fate.

Charpentier’s opera offers a somewhat different view. In the words of the unknown librettist, Juno’s commentary (none of which seems to derive from any translation of Ovid I’ve encountered) presents the goddess attempting to claim some credit for Acteon’s fate:

“Son infortune est mon ouvrage

Et Diane en vengeant l’outrage

Q’il fait à ses appas

N’a que prête sa main à ma jalousie rage.”

Whatever momentary satisfaction Juno derives is short-lived, as she is almost immediately provoked again by Jove’s dalliance with Semele. Juno remains furious but ineffectual to change Jove’s behavior or even to overcome her loss of prestige.

One available recording of Actéon (by the Boston Early Music Festival) bears on its cover a detail of a painting by the Italian mannerist Giuseppe Cesari showing Acteon at the moment when he arrives on the bathing scene and presumably has been splashed by the goddess. While I’m sure that the beautiful nudes are the center of attention for most viewers, what I also find most intriguing is that the story is moving ahead very quickly. Already Acteon is sporting antlers and three of his dogs are viewing him suspiciously, a foretaste of what is soon to befall him.

One available recording of Actéon (by the Boston Early Music Festival) bears on its cover a detail of a painting by the Italian mannerist Giuseppe Cesari showing Acteon at the moment when he arrives on the bathing scene and presumably has been splashed by the goddess. While I’m sure that the beautiful nudes are the center of attention for most viewers, what I also find most intriguing is that the story is moving ahead very quickly. Already Acteon is sporting antlers and three of his dogs are viewing him suspiciously, a foretaste of what is soon to befall him.Regrettably, I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing. Too bad, this one is quite spectacular.)

ARPINO. Steve and Jim, I need to read the text again and think about the literary points you raise. Meanwhile, though, I can post Jim's picture. Painted around 1603–06 by Giuseppe Cesari, perhaps better known as the Cavaliere d'Arpino, it is a couple of generations later than the Titian. The fact that it is painted on copper rather than canvas may account for the exquisite clarity and detail. It is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Spectacular indeed! R.

ARPINO. Steve and Jim, I need to read the text again and think about the literary points you raise. Meanwhile, though, I can post Jim's picture. Painted around 1603–06 by Giuseppe Cesari, perhaps better known as the Cavaliere d'Arpino, it is a couple of generations later than the Titian. The fact that it is painted on copper rather than canvas may account for the exquisite clarity and detail. It is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Spectacular indeed! R.

Roger, I would be interested to learn about your approach to staging the opera. Perhaps as a means of avoiding the awkward necessity of presenting Diana and her nymphs in all their glowing nudity, those productions I'm aware of seem to dress their cast in the most elaborate imaginable 18th century attire, as would have been seen at the court of Versailles, thereby keeping the ladies' charms well hidden. Perhaps the ever self-absorbed Juno would be pleased at this?

Roger, I would be interested to learn about your approach to staging the opera. Perhaps as a means of avoiding the awkward necessity of presenting Diana and her nymphs in all their glowing nudity, those productions I'm aware of seem to dress their cast in the most elaborate imaginable 18th century attire, as would have been seen at the court of Versailles, thereby keeping the ladies' charms well hidden. Perhaps the ever self-absorbed Juno would be pleased at this?

WIKIPEDIA. I have just been looking at the Wikipedia article on Actaeon. It is amazingly comprehensive, and well worth a look. Apparently there are many different versions of the myth, first in Greek and then Latin. The one common element is the huntsman devoured by his hounds, but accounts differ as to the cause of his offense, and how it came about.

WIKIPEDIA. I have just been looking at the Wikipedia article on Actaeon. It is amazingly comprehensive, and well worth a look. Apparently there are many different versions of the myth, first in Greek and then Latin. The one common element is the huntsman devoured by his hounds, but accounts differ as to the cause of his offense, and how it came about.One thing common to many different versions, however, is the listing of the hounds by name. Wikipedia even gives a comparative table. The names and origins are not made up by Ovid. Steve must be right in suggesting that it belongs to a different tradition of narrative, but I found I could easily enough accept it, and indeed the whole thing was quite lively in the Charles Martin translation. Several versions, apparently, extend into a sequel in which the hounds wander the earth, filled with remorse at what they had done.

Jim, I had forgotten that Juno appeared in Charpentier's Actéon; I wonder if we somehow left her out? It seems unreasonable of her to take the credit away from Diana, and utterly unjust to seek revenge on Actaeon just because her rival Europa was his great aunt. But that is applying modern standards.

By modern standards too, Actaeon might seem a pretty useless princeling. But a life devoted to the hunt was surely par for the course, and the enormous carnage merely shows that he was good at it. No, my sympathies are pretty much with him, suffering such a fate for no apparent fault of his own. R.

Funny how the fates work. A couple of days ago I was looking at a bronze platter that my wife has had for years on a bookshelf. I remembered that it was the Diana story but couldn’t remember the name of the guy being turned into a stag. And then at opened this email and saw it was Actaeon story, which I studied many years ago. Getting old will do this.

Funny how the fates work. A couple of days ago I was looking at a bronze platter that my wife has had for years on a bookshelf. I remembered that it was the Diana story but couldn’t remember the name of the guy being turned into a stag. And then at opened this email and saw it was Actaeon story, which I studied many years ago. Getting old will do this. The platter was a gift. What an odd gift? What remarkable coincidence. Thank you Goodreads people.

Jim wrote: "Roger, I would be interested to learn about your approach to staging the opera. Perhaps as a means of avoiding the awkward necessity of presenting Diana and her nymphs in all their glowing nudity, ..."

Jim wrote: "Roger, I would be interested to learn about your approach to staging the opera. Perhaps as a means of avoiding the awkward necessity of presenting Diana and her nymphs in all their glowing nudity, ..."Thanks for asking, Jim. Did you look at the link I sent? Glowing nudity indeed—or it would be glowing, had the lighting been brighter. The other version on YouTube, by Les Arts Florissants, dresses the women in modern gowns and moves them in decorous ways among the orchestra; the Nymph who sings the aria about forswearing love (Arthébuze) indicates that she is bathing by removing one shoe!

I think my production (I realize now that I largely entrusted the second one to its choreographer) was very like what you describe. It was part of a program of one-acts by Monteverdi, Charpentier, and Purcell called "Pastorale and Masque," and was given in the court of the Walters Art Museum under a magnificent statue of Apollo, over twice normal scale. In a more mundane setting, I might have flirted with apparent nudity, but the court costumes provided by our costume designer (who always preferred grandeur over simplicity) were absolutely right for that context.

Mostly, we relied upon establishing a private place for the women, separated off by a screen of stylized reeds. They also sat around in informal positions, or perhaps mimed splashing each other. I seem to remember that two or three of them held up a veil as a screen for Diana, so that we might imagine her getting undressed. But as I say, there is so much sensuality in the music that who needs more? R.

Even allowing for vast differences in social norms, I’m perplexed by Ovid’s fascination with the gory details of Acteon’s death. Despite usually being a model of brevity, Ovid goes on at great length, even naming over thirty of the dogs and describing every aspect of the attack. I would be interested if anyone else has an opinion about this.

Even allowing for vast differences in social norms, I’m perplexed by Ovid’s fascination with the gory details of Acteon’s death. Despite usually being a model of brevity, Ovid goes on at great length, even naming over thirty of the dogs and describing every aspect of the attack. I would be interested if anyone else has an opinion about this.

Roger, I agree that the sensuality of the music carries it. I'm intrigued of course that a story which is so brutal in many ways became the subject for such lush, graceful music. The production on the link you sent is true to the spirit of the music. It's all Charpentier, with just a nod to Ovid. Except for Juno, who injected a convincing note of vindictiveness. Interesting to note that her costume was probably more revealing than that of the nymphs.

Roger, I agree that the sensuality of the music carries it. I'm intrigued of course that a story which is so brutal in many ways became the subject for such lush, graceful music. The production on the link you sent is true to the spirit of the music. It's all Charpentier, with just a nod to Ovid. Except for Juno, who injected a convincing note of vindictiveness. Interesting to note that her costume was probably more revealing than that of the nymphs.

TITIAN 2012. Here is a short promo that I came across from the festival "Metamorphosis: Titian 2012," a collaboration between London's Royal Ballet and National Gallery. I have not looked to see what else may be there, but there are some fascinating threads to pick up. Roger.

TITIAN 2012. Here is a short promo that I came across from the festival "Metamorphosis: Titian 2012," a collaboration between London's Royal Ballet and National Gallery. I have not looked to see what else may be there, but there are some fascinating threads to pick up. Roger.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVgaK...

HUGHES/MATTHEWS. I looked up the Ted Hughes translation of the Actaeon story from his Tales from Ovid. It is lively but fairly straight, so I wasn't going to mention it.

HUGHES/MATTHEWS. I looked up the Ted Hughes translation of the Actaeon story from his Tales from Ovid. It is lively but fairly straight, so I wasn't going to mention it.But then I came upon this: a chamber music piece (2012) by David Matthews, in which the Hughes poem is beautifully read by Eleanor Bron, against and between passages of dramatic and highly expressive music. Even if only for the reading, I recommend it. R.

https://youtu.be/Wb-kAYraiqU

Roger, thank you for the link to that narrated chamber piece. To my ears, Matthews' music (though admittedly not in Charpentier's league) captures the spirit of the story quite brilliantly. I believe that when one embarks upon telling a story, music can accomplish a great deal more than is possible by means of a visual picture; it can reveal unspoken emotions, memories, fears, aspirations, regrets and so much more than can be seen on the surface. Even the greatest picture is static and at best three-dimensional while music is dynamic and multi-layered.

Roger, thank you for the link to that narrated chamber piece. To my ears, Matthews' music (though admittedly not in Charpentier's league) captures the spirit of the story quite brilliantly. I believe that when one embarks upon telling a story, music can accomplish a great deal more than is possible by means of a visual picture; it can reveal unspoken emotions, memories, fears, aspirations, regrets and so much more than can be seen on the surface. Even the greatest picture is static and at best three-dimensional while music is dynamic and multi-layered.

Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing. Too bad, this one is quite spectacular.).."

Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing. Too bad, this one is quite spectacular.).."Jim, for posting images, you need to do basically two things.

One is use the commands as indicated when you click (some html is ok) - I cannot type them now because they will work already as commands, but importan to use < to open and > to close as well as the inverted command.

And two, and the most tricky, is to get the internet address of the image you want to post. For this you need to put the mouse on top of the image and do a right click.. in the menu that will come up chose one of the following messages (the exact wording will depend on the Browser you use) - 'Copy Image address'; 'Copy Image Location'; . When you click on that option it will have already picked up its address. You then paste it into your comment in GR (framed by the html commands) and that should do the work.

Watch out that the image address does not look like a very long string of gibberish. If it does then the image is encrypted. You need to find the page where it is and try again to see wether you can get the non encrypted image.

The length and look of the non encrypted image address will look something like this:

https://studio360.files.wordpress.com...

I suggest you copy the above address (detail from an Acteon by Parmigianino) and try to 'frame' it with the html commands, and once you have mastered that first step you can then try with the addresses of other images you find and wish to post.

Good luck.

Roger wrote: "ACTAEON OPERA. Early on in Book III comes the story of Diana and Actaeon. This has special interest for me because I have done two productions of Actéon, the opera-pastorale written around 1680 by ..."

Roger wrote: "ACTAEON OPERA. Early on in Book III comes the story of Diana and Actaeon. This has special interest for me because I have done two productions of Actéon, the opera-pastorale written around 1680 by ..."Thank you Roger for your posts on the Charpentier opera... I will watch the YouTube recordings and come back... I may try to get the recording Jim mentions.

Incidentally, I have been reading lately and listening to other 17C music in relation to Casanova (I am reading his memoirs now and he talks about Lully and Rameau in his Preface) and Watteau (reading a couple of books on him), and considering various recordings for my Xmas stocking...

:)

To Steve and Jim - about the dogs...

To Steve and Jim - about the dogs...I had no problem with the enumeration of the dogs.. It made me think of oral traditions, and also that this work and its stories were addressed to a culture that enjoyed hunting and fights. Good dogs were precious and to be able to watch a pack of thirty plus dogs pushing themselves to the extreme must have been considered quite an spectacle.

Ovid is giving dimension to this scene by making it more concrete.

Actaeon's companions call him because they think he is missing quite something. And Actaeon himself would have liked to have been able to watch the kill - rather than suffer it.

In Actaeon's 'punishment' I see first of all a wish in Diana's part to prevent him from TALKING and telling others that he has seen her naked. Again the recurrent theme of the loss of speech. At least Io could write her name and make her father understand who she is. Had Actaeon being able to communicate, he would have saved himself - at least from being killed.

In Actaeon's 'punishment' I see first of all a wish in Diana's part to prevent him from TALKING and telling others that he has seen her naked. Again the recurrent theme of the loss of speech. At least Io could write her name and make her father understand who she is. Had Actaeon being able to communicate, he would have saved himself - at least from being killed. Mostly it is the female who have their speaking abilities taken away, but Actaeon is the second male (the first was Battus - who was turned into stone).

Then the being killed by his own dogs is a result of his dogs and companions not recognising him.

Juno, vindictive as she is, is delighted of this tragedy. She always turns against the victims, not the doer.

In the 'Post des Arts' in Paris there was an exhibition of modern sculpture with one Actaeon composition.

In the 'Post des Arts' in Paris there was an exhibition of modern sculpture with one Actaeon composition.

But I loved the sculpture in Caserta, Roger. Thank you... the fountain/pond is the perfect place for such a composition.

But I loved the sculpture in Caserta, Roger. Thank you... the fountain/pond is the perfect place for such a composition.

We have jumped over Cadmus. The beginning of the chapter made me think of The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, which I read many years ago and may revisit after we finish with Ovid.

We have jumped over Cadmus. The beginning of the chapter made me think of The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, which I read many years ago and may revisit after we finish with Ovid.Interesting that Cadmus endured exile, as Ovid would himself suffer after (?¿) he finished the Met.

As we do not have the original manuscripts but only Medieval copies it must be very hard to try and ascertain how much, if at all he revised while in exile.

Anyway, the most famous painting is that by

Jacob Jordaens. 1636-38. Prado.

Based on a Rubens sketch. Private collection.

This formed part of the decoration program for the Torre de la Parada - the hunting lodge of Philip IV.

Rubens has conflated the various stages of the story. The snake has just been killed, Minerva is there, and the teeth have been transformed into young fighting warriors.

But the version by Hendrik Goltzius (we've seen several of his prints in the earlier themes) has a more interesting rendition of the serpent.. here with three heads - not just three rows of teeth and three tongues.

But the version by Hendrik Goltzius (we've seen several of his prints in the earlier themes) has a more interesting rendition of the serpent.. here with three heads - not just three rows of teeth and three tongues.Goltzius began as an engraver but moved into painting later in his career.

Hendrik Goltzius. 1573-1613. Koldinghus, Denmark.

In the scene in which the men spring from the planted teeth.

In the scene in which the men spring from the planted teeth.My Simpson edition clarifies that "in Roman theatres the curtains were raised or lowered from the floor, lie a window shade, but in reverse. It was down at the beginning of the play, so that the stage was visible, and was dawn up at the end, in order to cover it. As it was being drawn up figures inwoven or painted on it would gradually become visit.e, firs their heads, finally their feet."

I was a bit confused when I read in the Ovid text that as the curtain was raised, one saw the faces first...

I'm late to the party here... but yes, the 'catalogue' of hounds names in the Actaeon story is, surely, a humorous riff on the 'catalogue of ships' in the Iliad? And those other listings that epic loves so much.

I'm late to the party here... but yes, the 'catalogue' of hounds names in the Actaeon story is, surely, a humorous riff on the 'catalogue of ships' in the Iliad? And those other listings that epic loves so much.On the unfairness of Actaeon's punishment, is the real Ovid having a dig at his own exile, possibly as an excessive punishment? I'd like to think so.

Roger, thank you for so many rich references here! I especially love those Actaeon sculptures in their setting - stunning!

Kalliope wrote: "To Steve and Jim - about the dogs...

Kalliope wrote: "To Steve and Jim - about the dogs...I had no problem with the enumeration of the dogs.. It made me think of oral traditions, and also that this work and its stories were addressed to a culture th..."Naming the dogs always reminds me of Santa's reindeer, I think it is a kind of oral history trope...

Elena wrote: "Naming the dogs always reminds me of Santa's reindeer, I think it is a kind of oral history trope..."

Elena wrote: "Naming the dogs always reminds me of Santa's reindeer, I think it is a kind of oral history trope..."Haha.. Santa is being pulled by young Actaeons...

More on the dogs...

More on the dogs... Wiki has a whole chart comparing the names of Ovid's dogs with those in other accounts..Apollodorus's and Others...!!!

Entry on Actaeon.

Kalliope wrote: "Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing. Too bad, this one is quite spectacular.).."

Kalliope wrote: "Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing. Too bad, this one is quite spectacular.).."Jim, for posting images, you need to do b..."

Thank you very much for your help, Kalliope! On e would think that after a number of years on GR I would have learned all this.

Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing."

Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing."Kalliope's approach is undoubtedly the simplest. I, however, copy the pictures first to my own website, where I can edit, crop, or combine them, and know that they won't suddenly disappear. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: ... but yes, the 'catalogue' of hounds names in the Actaeon story is, surely, a humorous riff on the 'catalogue of ships' in the Iliad? And those other listings that epic loves so much. ..."

Roman Clodia wrote: ... but yes, the 'catalogue' of hounds names in the Actaeon story is, surely, a humorous riff on the 'catalogue of ships' in the Iliad? And those other listings that epic loves so much. ..."Indeed, the listing gave also me a smile at first. Then I looked at the Latin text and read it allowed. Even if I did not understand all the words, the mere sound of them was impressive - almost as impressive as dog names in the American Kennel Club. On a second thought the list of names reminded me of the long list of decendants of Noah in the Bible (Genesis 11, 10 - 26), which gives the story an air of objectivity.

Peter, I think you've hit on the real reason for the catalog of dogs! The reference to the descendants of Noah makes sense. Ovid was reaching for authenticity: If this guy can reel off all those facts, he must be the real deal!

Peter, I think you've hit on the real reason for the catalog of dogs! The reference to the descendants of Noah makes sense. Ovid was reaching for authenticity: If this guy can reel off all those facts, he must be the real deal!

OLDER CADMUS IMAGES. Here are three older images of the Cadmus story. The krater image is from Wikipedia, and is rather splendid, though the dragon is not very fearsome. The Etrucsan relief is a lot more scary. I do rather like the Italian one, though, with the rather sweet toy dragon at right and the two youths on the left looking entirely unconcerned! R.

OLDER CADMUS IMAGES. Here are three older images of the Cadmus story. The krater image is from Wikipedia, and is rather splendid, though the dragon is not very fearsome. The Etrucsan relief is a lot more scary. I do rather like the Italian one, though, with the rather sweet toy dragon at right and the two youths on the left looking entirely unconcerned! R.

Calix krater, 4th century BCE. Paris, Louvre.

Etruscan chest from Volterra, 2nd century BCE.

Verona, 15th century.

CADMUS BY GOLTZIUS. Kalliope posted a painting by Hendrik Goltzius. Here are three of his engravings from earlier in the story, and a painting (or ink drawing) that prepares for his print of Cadmus's actual attack. I find the last four quite splendid in their depiction of the dragon, and the balance between man and monster really terrifying. [I am not sure of the accuracy of all this information; Google Image Search is an imperfect tool.] R.

CADMUS BY GOLTZIUS. Kalliope posted a painting by Hendrik Goltzius. Here are three of his engravings from earlier in the story, and a painting (or ink drawing) that prepares for his print of Cadmus's actual attack. I find the last four quite splendid in their depiction of the dragon, and the balance between man and monster really terrifying. [I am not sure of the accuracy of all this information; Google Image Search is an imperfect tool.] R.

Cadmus asking the Delphic Oracle about Europa.

The dragon attacking the companions of Cadmus.

The dragon devouring the companions of Cadmus. This is a copy of the 1588 painting by Cornelius van Haarlem now posted at comment 3/232.

Cadmus attacking the dragon (tinted drawing).

The engraved version of the above.

TWO MORE. Two more later Cadmus pictures, and then I am done. After all that Northern bloodshed, I like the French elegance of the victorious Cadmus in the Blanchet painting receiving Minerva's suggestion that he sow the dragon's teeth. Zuccarelli was an Italian who settled in England and was elected to the Royal Academy; hence his presence in the Tate. His picture is an Arcadian landscape in the tradition of Claude, with the mythological subject very much secondary. R.

TWO MORE. Two more later Cadmus pictures, and then I am done. After all that Northern bloodshed, I like the French elegance of the victorious Cadmus in the Blanchet painting receiving Minerva's suggestion that he sow the dragon's teeth. Zuccarelli was an Italian who settled in England and was elected to the Royal Academy; hence his presence in the Tate. His picture is an Arcadian landscape in the tradition of Claude, with the mythological subject very much secondary. R.

Thomas Blanchet: Cadmus and Minerva, c.1680.

Francesco Zuccarelli: Landscape with the Story of Cadmus, 1765. London, Tate.

The archetype of dragon seems to have been known since the most ancient times…

The archetype of dragon seems to have been known since the most ancient times…“When Pallas swift descending from the skies,

Pallas, the guardian of the bold and wise,

Bids him plow up the field, and scatter round

The dragon’s teeth o’er all the furrow’d ground;

Then tells the youth how to his wond’ring eyes

Embattled armies from the field should rise.

He sows the teeth at Pallas’s command,

And flings the future people from his hand.”

And the sowing of the dragon’s teeth have afterwards become the attribute of many fairytales.

Jim wrote: "On e would think that after a number of years on GR I would have learned all this. .."

Jim wrote: "On e would think that after a number of years on GR I would have learned all this. .."Jim, if you still want to have a go, I suggest you copy the imaged address I posted above and try whether it works for the commands - if so then you just have to concentrate on the getting the image address.

Vit wrote: "The archetype of dragon seems to have been known since the most ancient times…

Vit wrote: "The archetype of dragon seems to have been known since the most ancient times…."

Gosh, yes, the dragon is such a pervasive element in ancient cultures.. that is a perduring symbol...!!!

Roger wrote: "CADMUS BY GOLTZIUS. .."

Roger wrote: "CADMUS BY GOLTZIUS. .."Thank you, Roger.. yes, Goltzius treated them all... when we don't have any outstanding paintings there are always his engravings since he illustrated the entire work.

That is why I find it striking that even though he had a pictorial repertory for the entire poem, he chose this particular myth once he moved to this other medium.

Roger wrote: "OLDER CADMUS IMAGES..."

Roger wrote: "OLDER CADMUS IMAGES..."The Louvre krater is a popular one.. I like the Verona version you posted. I did not know it.

Going back to the Actaeon, as with other myths, Titian's poesie for Philip II, clearly come at the top. But with its display of nudity and the theme of 'voyerism' and the hunting context it would prove to be one of the enduring myths.

Going back to the Actaeon, as with other myths, Titian's poesie for Philip II, clearly come at the top. But with its display of nudity and the theme of 'voyerism' and the hunting context it would prove to be one of the enduring myths.It is interesting to see to which of the two aspects, the nude or the hunt does the painter give more attention.

A few less well-known ones:

Giacomo Ceruti. 1744. Palazzo Arconati Visconti, Milan

And, at least for me, an unlikely candidate:

Gainsborough. 1785-88. Royal Collection.

(view spoiler)

An appealing subject for a painter who has sort of gone out of fashion even though he inspired the settings of many Hollywood movies on Roman times. I like him; he is peculiar.

Jean-Léon Gérôme. 1890s. Private Collection.

The scene has been transposed to more modern times - notice the hunters riding in the background - wearing the red jackets. Haha. I love the colours.

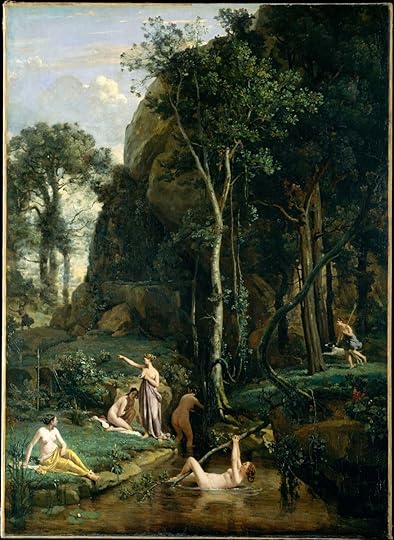

And then by the painter who inspired the Impressionists. Emphasis on the landscape again.

Camille Corot. 1836. Metropolitan, NY.

All the above post-Titian. Before him we have also this delightful one by Cranach. An entirely different conception. Cranach liked these ponds with naked women.

Lucas Cranach the Elder. 1528. Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT.

The pictorial repertoire seems endless.. Another winner - like Europa.

Kalliope wrote: "It is interesting to see to which of the two aspects, the nude or the hunt does the painter give more attention."

Kalliope wrote: "It is interesting to see to which of the two aspects, the nude or the hunt does the painter give more attention."I thought that question was obvious: to the nudes! There are certainly some who have given as much or more attention to the landscapes (such as the Gainsborough or the Corot), but do you really know of any who have emphasized the hunt when there are naked women around?

Thank you for posting the Gérôme; I did not know it at all. Once again, the nudes are what it is all about, but the image of the hounds coming down the hill is a real invention. You don't see Actaeon spying, though, do you? And for that, he would need to be separated from the rest of the hunt. R.

Kalliope wrote: "The pictorial repertoire seems endless. Another winner—like Europa."

Kalliope wrote: "The pictorial repertoire seems endless. Another winner—like Europa."Late last night, I added a slightly tongue-in-cheek post (#71) to the General Chat section of the group. I was suggesting that we could rate the various stories on their fecundity factor: the degree to which they have inspired illustrations and other retellings in later centuries. More seriously, I asked why some should be more pervasive than others.

Europa and Actaeon, as you say, are winners in this regard. If we confine ourselves to painting, then one obvious reason is the excuse they give for portraying nudes or sexually suggestive scenes. But when they give rise to other poetry, to music, and to versions in other arts, then the pictorial possibilities alone do not explain the popularity.

Just for these two: I had heard the story of Europa way, way back; but I did not know the details of Actaeon until I had to direct the opera. Now I am wondering why. Roger.

Not to undermine the importance of Europa as a visual inspiration, but in terms of poetry I'd suggest Daphne and Apollo as far more fecund: the dynamics of the male pursuit of a cold/uninterested female beloved is institutionalized in Roman love poetry (Catullus, Propertius, Ovid's own Amores) then transmitted into the Renaissance via Petrarch (Thomas Wyatt, Philip Sidney) and resurfaces beyond (Keats' La Belle Dame Sans Merci, for example). The trope remains alive because it can be developed, twisted and renewed.

Not to undermine the importance of Europa as a visual inspiration, but in terms of poetry I'd suggest Daphne and Apollo as far more fecund: the dynamics of the male pursuit of a cold/uninterested female beloved is institutionalized in Roman love poetry (Catullus, Propertius, Ovid's own Amores) then transmitted into the Renaissance via Petrarch (Thomas Wyatt, Philip Sidney) and resurfaces beyond (Keats' La Belle Dame Sans Merci, for example). The trope remains alive because it can be developed, twisted and renewed.

Actaeon is also a story, for me, of abuse of power and unjustified punishment: Actaeon doesn't intend offence, sees Diana by mistake - yet is ripped apart gorily by his own hounds.

Actaeon is also a story, for me, of abuse of power and unjustified punishment: Actaeon doesn't intend offence, sees Diana by mistake - yet is ripped apart gorily by his own hounds. It speaks back, surely, to the Lycaon story where Jupiter destroys the whole world for one man's act of transgression, another excessive punishment.

Given that Ovid early equated the Olympian gods with Augustus and the Roman elite, this is surely a politicised commentary on his contemporary world - as well as having relevance beyond.

I knew you would have helpful answers to my query, Roman Clodia! Thank you. Now you mention its poetic legacy, I agree with you about the Daphne story. I also take your implication that the fecundity of a trope has much to do with its fungibility, or as you say, its ability to be "developed, twisted, and renewed."

I knew you would have helpful answers to my query, Roman Clodia! Thank you. Now you mention its poetic legacy, I agree with you about the Daphne story. I also take your implication that the fecundity of a trope has much to do with its fungibility, or as you say, its ability to be "developed, twisted, and renewed."In the post below that, you also remind us of the significance of Ovid's myth as political commentary. Though there are some others here who share your knowledge, I am afraid that few general readers have the knowledge of history to read Ovid in this way, so once again your reminders are welcome. Roger.

Books mentioned in this topic

The Greek Myths (other topics)The Greek Myths (other topics)

The Golden Fleece (other topics)

The Grove Book of Operas (other topics)

Los mitos en el Museo del Prado (other topics)

More...