The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Barnaby Rudge

>

Barnaby Rudge Chapters 6-10

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 7

This chapter further introduces us to the Varden household. We learn that Mrs Varden has “a capricious nature” and that her moods swing wildly from moment to moment. Mrs Varden has a domestic maid whose name is Miss Miggs, or just Miggs. Mrs Varden and Miggs are physical opposites. Miggs is tall and thin; Mrs. Varden is the opposite. She finds the male sex “contemptible and unworthy of notice.” Miggs enjoys coming to Mrs Varden’s defence, and is quite happy to speak her mind and share her opinions openly to both Mr and Mrs Varden. It also seems that whenever Miggs or Mrs Varden are part of a scene or event the reader should be prepared for some tears of emotion, if not hysteria. Throughout the chapter Dickens works to establish the calm demeanour of the locksmith and contrast it with the volatility of his wife and Miggs. Dickens also employs a bit of humour when he has the locksmith muse if “there is any madman alive, who would marry Miggs!”

As the chapter closes and the Varden’s and Miggs settle into their respective sleep, Varden’s apprentice Sim Tappertit produces a secret key to the front door of the house and slips into the night.

Thoughts

For what reasons would Dickens write this rather short chapter?

The chapter ends not with the characters who carried the substance of the chapter but with Sim slinking into the night. What might be the purpose of the last paragraph of the chapter?

This chapter further introduces us to the Varden household. We learn that Mrs Varden has “a capricious nature” and that her moods swing wildly from moment to moment. Mrs Varden has a domestic maid whose name is Miss Miggs, or just Miggs. Mrs Varden and Miggs are physical opposites. Miggs is tall and thin; Mrs. Varden is the opposite. She finds the male sex “contemptible and unworthy of notice.” Miggs enjoys coming to Mrs Varden’s defence, and is quite happy to speak her mind and share her opinions openly to both Mr and Mrs Varden. It also seems that whenever Miggs or Mrs Varden are part of a scene or event the reader should be prepared for some tears of emotion, if not hysteria. Throughout the chapter Dickens works to establish the calm demeanour of the locksmith and contrast it with the volatility of his wife and Miggs. Dickens also employs a bit of humour when he has the locksmith muse if “there is any madman alive, who would marry Miggs!”

As the chapter closes and the Varden’s and Miggs settle into their respective sleep, Varden’s apprentice Sim Tappertit produces a secret key to the front door of the house and slips into the night.

Thoughts

For what reasons would Dickens write this rather short chapter?

The chapter ends not with the characters who carried the substance of the chapter but with Sim slinking into the night. What might be the purpose of the last paragraph of the chapter?

Chapter 8

This chapter will be devoted to Mr Varden’s apprentice named Sim Tappertit. First, we learn that Sim has made a copy of the Varden household’s front door key. Obviously, Sim is not the best or most honest of characters or apprentices. We follow his night ramble to a rather dodgy part of town that is “reeking with stagnant odours.” Here he stops in front of a house and strikes upon a grating three times with his foot. He enters and descends a very “narrow, steep, and slippery flight of stairs.” Did you notice how the first people he met treated Sim with deference? It seems that Sim envisions himself as a great commander. He is greeted with the words “Welcome, Noble Captain.” Sim is conducted to a seedy room that smells of cheeses and is damp with “little trees of fungus [hanging] from every mouldering corner.” Yuck! Regardless of the surroundings, Sim is quite haughty and self-absorbed with himself.

What we have in this damp basement is a collection of apprentices who have fashioned the name of ‘Prentice Knights to describe themselves. Their charter can be summed up with the words “Death to all masters, life to all ‘prentices, and love to all fair damsels.” This group of conspirators are interested in righting the wrongs done to them by their masters and the winning of hearts of beautiful young women. In a way, we seem to have a parody of the concept of romantic chivalry. Still, this motley group of men should be watched carefully. Any group that meets in secret and functions under the belief that they are oppressed need to be monitored carefully. This is especially true when we reflect upon the fact that this novel is constructed around an historical event.

Sim may not be the prototypical leader but he does look upon himself as a leader; equally, he looks down upon his legs which, to him anyway, are beautiful, classical and worth endless admiration. I know of few, if any, leaders who consider their legs to be their chief asset. We might be in for some good humour if we follow Sim’s attitude and character.

This rag-tag group invest a novice into their secret society and denounce his master with “vengeance complete and terrible.” Once the investiture is complete our ‘Prentice Knights seal their fraternity of hating their masters and lusting after women with a drink. It comes as no surprise that the damsel that Sim lusts after is Dolly. This will make him the arch foe of Joe Willet. We also learn that Sim is responsible for making keys for the other members from wax impressions so they can sneak away from their masters and attend these meetings.

Our chapter comes to a close as the night moves towards the dawn. Our apprentices must all return to their respective masters’ homes. Stagg, a blind member of the ‘Prentices, who initially let Sim in, locks up the grate and prepares for a day of selling broth and soup.

Thoughts

Here we have another chapter in which Dickens introduces us, in more detail, to a character. What are your impressions of Sim Tappertit? From these early chapters do you see him becoming a good or bad character?

Did you find this chapter to be humourous in any way?

In this chapter we have been introduced to a group of people who meet in secret. They have some format of organization, some rituals, a single-minded focus, and a clear dislike, if not hatred, of another identifiable group of people. Why might Dickens take the time to introduce the idea of secret societies or disruptive groups to the story?

Dickens often identifies a specific speech pattern or physical feature to his characters. It appears Sim is rather proud of his legs. Any early speculation to what this might symbolize or lead to in future chapters?

Stagg is an interesting character. He acts as the gatekeeper for the ‘Prentice Knights. He is blind. The location of the group meetings in below ground. Hmmm ... a blind gatekeeper, a below ground meeting place ... just sets some of my bells off. Do you think any of these facts could important to our story? Care to make any early speculations?

Has any character or action to date seemed to suggest what is .yet to come? If so who, and why?

This chapter will be devoted to Mr Varden’s apprentice named Sim Tappertit. First, we learn that Sim has made a copy of the Varden household’s front door key. Obviously, Sim is not the best or most honest of characters or apprentices. We follow his night ramble to a rather dodgy part of town that is “reeking with stagnant odours.” Here he stops in front of a house and strikes upon a grating three times with his foot. He enters and descends a very “narrow, steep, and slippery flight of stairs.” Did you notice how the first people he met treated Sim with deference? It seems that Sim envisions himself as a great commander. He is greeted with the words “Welcome, Noble Captain.” Sim is conducted to a seedy room that smells of cheeses and is damp with “little trees of fungus [hanging] from every mouldering corner.” Yuck! Regardless of the surroundings, Sim is quite haughty and self-absorbed with himself.

What we have in this damp basement is a collection of apprentices who have fashioned the name of ‘Prentice Knights to describe themselves. Their charter can be summed up with the words “Death to all masters, life to all ‘prentices, and love to all fair damsels.” This group of conspirators are interested in righting the wrongs done to them by their masters and the winning of hearts of beautiful young women. In a way, we seem to have a parody of the concept of romantic chivalry. Still, this motley group of men should be watched carefully. Any group that meets in secret and functions under the belief that they are oppressed need to be monitored carefully. This is especially true when we reflect upon the fact that this novel is constructed around an historical event.

Sim may not be the prototypical leader but he does look upon himself as a leader; equally, he looks down upon his legs which, to him anyway, are beautiful, classical and worth endless admiration. I know of few, if any, leaders who consider their legs to be their chief asset. We might be in for some good humour if we follow Sim’s attitude and character.

This rag-tag group invest a novice into their secret society and denounce his master with “vengeance complete and terrible.” Once the investiture is complete our ‘Prentice Knights seal their fraternity of hating their masters and lusting after women with a drink. It comes as no surprise that the damsel that Sim lusts after is Dolly. This will make him the arch foe of Joe Willet. We also learn that Sim is responsible for making keys for the other members from wax impressions so they can sneak away from their masters and attend these meetings.

Our chapter comes to a close as the night moves towards the dawn. Our apprentices must all return to their respective masters’ homes. Stagg, a blind member of the ‘Prentices, who initially let Sim in, locks up the grate and prepares for a day of selling broth and soup.

Thoughts

Here we have another chapter in which Dickens introduces us, in more detail, to a character. What are your impressions of Sim Tappertit? From these early chapters do you see him becoming a good or bad character?

Did you find this chapter to be humourous in any way?

In this chapter we have been introduced to a group of people who meet in secret. They have some format of organization, some rituals, a single-minded focus, and a clear dislike, if not hatred, of another identifiable group of people. Why might Dickens take the time to introduce the idea of secret societies or disruptive groups to the story?

Dickens often identifies a specific speech pattern or physical feature to his characters. It appears Sim is rather proud of his legs. Any early speculation to what this might symbolize or lead to in future chapters?

Stagg is an interesting character. He acts as the gatekeeper for the ‘Prentice Knights. He is blind. The location of the group meetings in below ground. Hmmm ... a blind gatekeeper, a below ground meeting place ... just sets some of my bells off. Do you think any of these facts could important to our story? Care to make any early speculations?

Has any character or action to date seemed to suggest what is .yet to come? If so who, and why?

Chapter 9

If you are like me, Dickens’s humour is always a treat. A study of minor characters are often wonderful places to find such humour. Well, let’s look at this chapter that features Sim and Miggs. Have you noticed in previous Dickens novels - with the exception of The Pickwick Papers Mr Pickwick - how the humour of the novel is generally brought to us by the minor characters? Why might that be?

Chapter 9 begins with a narrative comment by Dickens. He reminds his readers that writers can go where they want to go, see what they want to see, and either compress or elongate time. For this chapter, he takes us into the bedroom of Miggs, and rolls back the time spent in the last chapter so we can see what Miggs was up to as Sim was off at his secret meeting. We begin by seeing Miggs looking out her little attic window. She hears Sim in his room next to hers and Dickens hints that perhaps Sim “sometimes dreamed of her.” Miggs continues to listen and wonders if Sim is about to enter her room. Her door is not fastened! She peeks outside her room sees Sim dressed then descend the stairs and go through the parlour-door and then out the street-door. He then closes the door from the outside, locks it, and “swaggered off, putting something in his pocket as he went along.” Miggs then goes down the stairs herself, discovers the door is locked, and realizes that Sim has made a key for the front door. Miggs calls Sim a villain and recalls earlier times when she has caught him busy on some occupation. Here we get the final conformation of how all the apprentices get out of their masters’ homes at night. Sim has made them all keys. Miggs then takes a piece of paper, makes it into a long straw, fills it with coal dust from the forge, and blows all the dust into the keyhole. Going upstairs again Miggs is quite pleased with herself and mutters that now Sim will have to take some notice of her.

Miggs then sets up to watch for Sim for the remainder of the night. As dawn comes Sim returns home, but for all his efforts cannot get his key to work in the lock. Miggs enjoys his struggle and the reader enjoys all his fruitless antics to unlock the door. Then Miggs pokes her head out the window, and acting as an innocent, plays upon Sim’s discomfort at not being able to get into the locked house. Playing the innocent in this farcical confrontation, Miggs gets Sim to change his tactics from begging to be secretly let in by wooing Miggs and calling her “darling” and telling her that he loves her and “can’t help but [think] of her.” Miggs tells Sim that if she comes down and lets him in she is sure he will try and kiss her to which he replies “I swear I won’t.” Miggs goes downstairs and opens a window to let Sim in, mutters the words “Simmun is safe” and “immediately became insensible.” Sim takes Miggs in his arms, carries her upstairs and “plants” her inside her own door.” Sim leaves and Miggs, who has been feigning her swoon, comments to herself “I’m in his confidence and he can’t help himself.”

Thoughts

The last two chapters have been focussed on two minor characters. Which chapter/character did you enjoy the most? Why?

Do you think Sim has any romantic interest in Miggs at all? Do you think Miggs has any romantic interest in Sim?

This short chapter seems to have many key (pun intended :-))elements to it such as character development and humour. Why else might this chapter be important as we progress through the novel?

Dickens has incorporated a melodramatic and very theatrical format to this chapter. We have the midnight sneaking about of characters, doors and windows opening and closing, misplaced or misunderstood love possibilities, and a touch of farce. Do you enjoy such chapters?

We saw how Dickens used keys as objects that had much symbolic and sexually suggestive in The Old Curiosity Shop. Here again in this novel, keys have made an early and perhaps important entrance in the novel. Do you have any early thoughts as to what Dickens may be moving towards with his use of keys in this chapter?

If you are like me, Dickens’s humour is always a treat. A study of minor characters are often wonderful places to find such humour. Well, let’s look at this chapter that features Sim and Miggs. Have you noticed in previous Dickens novels - with the exception of The Pickwick Papers Mr Pickwick - how the humour of the novel is generally brought to us by the minor characters? Why might that be?

Chapter 9 begins with a narrative comment by Dickens. He reminds his readers that writers can go where they want to go, see what they want to see, and either compress or elongate time. For this chapter, he takes us into the bedroom of Miggs, and rolls back the time spent in the last chapter so we can see what Miggs was up to as Sim was off at his secret meeting. We begin by seeing Miggs looking out her little attic window. She hears Sim in his room next to hers and Dickens hints that perhaps Sim “sometimes dreamed of her.” Miggs continues to listen and wonders if Sim is about to enter her room. Her door is not fastened! She peeks outside her room sees Sim dressed then descend the stairs and go through the parlour-door and then out the street-door. He then closes the door from the outside, locks it, and “swaggered off, putting something in his pocket as he went along.” Miggs then goes down the stairs herself, discovers the door is locked, and realizes that Sim has made a key for the front door. Miggs calls Sim a villain and recalls earlier times when she has caught him busy on some occupation. Here we get the final conformation of how all the apprentices get out of their masters’ homes at night. Sim has made them all keys. Miggs then takes a piece of paper, makes it into a long straw, fills it with coal dust from the forge, and blows all the dust into the keyhole. Going upstairs again Miggs is quite pleased with herself and mutters that now Sim will have to take some notice of her.

Miggs then sets up to watch for Sim for the remainder of the night. As dawn comes Sim returns home, but for all his efforts cannot get his key to work in the lock. Miggs enjoys his struggle and the reader enjoys all his fruitless antics to unlock the door. Then Miggs pokes her head out the window, and acting as an innocent, plays upon Sim’s discomfort at not being able to get into the locked house. Playing the innocent in this farcical confrontation, Miggs gets Sim to change his tactics from begging to be secretly let in by wooing Miggs and calling her “darling” and telling her that he loves her and “can’t help but [think] of her.” Miggs tells Sim that if she comes down and lets him in she is sure he will try and kiss her to which he replies “I swear I won’t.” Miggs goes downstairs and opens a window to let Sim in, mutters the words “Simmun is safe” and “immediately became insensible.” Sim takes Miggs in his arms, carries her upstairs and “plants” her inside her own door.” Sim leaves and Miggs, who has been feigning her swoon, comments to herself “I’m in his confidence and he can’t help himself.”

Thoughts

The last two chapters have been focussed on two minor characters. Which chapter/character did you enjoy the most? Why?

Do you think Sim has any romantic interest in Miggs at all? Do you think Miggs has any romantic interest in Sim?

This short chapter seems to have many key (pun intended :-))elements to it such as character development and humour. Why else might this chapter be important as we progress through the novel?

Dickens has incorporated a melodramatic and very theatrical format to this chapter. We have the midnight sneaking about of characters, doors and windows opening and closing, misplaced or misunderstood love possibilities, and a touch of farce. Do you enjoy such chapters?

We saw how Dickens used keys as objects that had much symbolic and sexually suggestive in The Old Curiosity Shop. Here again in this novel, keys have made an early and perhaps important entrance in the novel. Do you have any early thoughts as to what Dickens may be moving towards with his use of keys in this chapter?

Chapter 10

This chapter takes us from London and brings us, once again, to the Maypole Inn. John Willet hears the sound of a horse’s feet and notices that a traveller “of goodly promise” has arrived at the Maypole’s door. The man is described as a “grave, and placid gentleman, something past the prime of life, yet upright in his carriage.” Willet knows this is a gentleman, and goes to greet the visitor. The following conversation between Willet and the gentleman establishes the gentleman as quiet, self-assured, slightly sarcastic, and exceedingly calm in his demeanour. Willet leads the man to the Maypole's best apartment. This room, while large, is described as having “the melancholy aspect of grandeur in decay, and was much too vast for comfort.” We are told that Willet had made no attempt “to furnish this chilly waste.”

Thoughts

In this chapter Dickens presents a new character but takes his time and unfolds this person’s appearance and characteristics very slowly. Rather than simply giving us the rider’s name we see Dickens subtlety informing us of the gentleman in two distinct ways. First, let’s notice the gentleman’s speech patterns. What is your initial impression of the man from his manner of speaking to Willet? Second, and I think as telling, is the description of the room that he will occupy. How would you feel if you were ushered into this room? Very often, almost always in fact, the rooms or the buildings that a character occupies in a Dickens provide a framework for the character, their personality, and their place within the arc of the plot. For example, through Sim’s sneaking down the stairs at Varden’s home, and then being ushered into the underground cavern-like rooms where the ‘Prentice Knights meet, the reader gets a broader understanding of Sim’s character. What could we presume about this gentleman by reflecting upon the room Dickens has placed him in?

The gentleman requests a pen, ink, and paper. He is obviously going to write a note. He wants the note to be immediately taken to the Warren. John Willet does not have his reliable son available to deliver the note, but tells the guest that he has someone else who can deliver the note, a person who is “touched and flighty.” Immediately, the guest knows that Willet is referring to Barnaby. But wait a minute! How could a traveller know the name of Barnaby from such a description? What does that suggest? The strange guest then comments that he saw Barnaby in London last evening. The guest seems to know that Barnaby often goes to the Warren. John tells the guest that Barnaby’s father was murdered at the Warren. The guest reply’s he knows that fact. Finally we learn that the guest’s name is Mr Chester. Barnaby is to take the note to Mr Haredale, wait for a response, and bring it back to the Maypole.

Thoughts

We learn that Mr Haredale and Mr Chester have a long and antagonistic history. The messenger is Barnaby. To what extent could this part of the plot be important. For fun, speculate of how it might be important.

Mr Chester awaits Barnaby’s return, which is so slow that Chester decides he will spend the night at the Maypole rather than risk being “knocked on the head” as his son has the night before. As Chester is settling in for the night Barnaby returns with the news that Haredale will be at the Maypole in an hour. Barnaby then bends down and gazes at the smoke from the chimney. Barnaby’s speech about the smoke could be a stream of conscious, or an unfocused ramble or it could be symbolic and offering the reader insight into future events yet to occur. How do you think the reader is to take Barnaby’s seemingly flights of verbal fantasy? I can’t help but keep thinking of the Fool in King Lear. How should a reader go about untangling the words of such characters?

We now have witnessed the first meeting between Haredale and Chester. What are your initial impressions of the pair?

Reflections

The novel is off to a quick start. We have already been introduced to a series of interesting characters. We have two major settings, one being London, and one being the Maypole and the surrounding countryside. Our mysteries are already piling up:

What is the reason or nature of the apparent hostility between Haredale and Chester?

Who is the mysterious person that lurks in the shadows of the first chapters?

For what purpose has Dickens created the ‘Prentice Knights?

It appears that Dickens is creating a series of father-son combinations of characters? What might he be up to with this plot device?

How are we to interpret the character and conversations of Barnaby Rudge?

Much more is to come. Enjoy your week’s reading my friends.

This chapter takes us from London and brings us, once again, to the Maypole Inn. John Willet hears the sound of a horse’s feet and notices that a traveller “of goodly promise” has arrived at the Maypole’s door. The man is described as a “grave, and placid gentleman, something past the prime of life, yet upright in his carriage.” Willet knows this is a gentleman, and goes to greet the visitor. The following conversation between Willet and the gentleman establishes the gentleman as quiet, self-assured, slightly sarcastic, and exceedingly calm in his demeanour. Willet leads the man to the Maypole's best apartment. This room, while large, is described as having “the melancholy aspect of grandeur in decay, and was much too vast for comfort.” We are told that Willet had made no attempt “to furnish this chilly waste.”

Thoughts

In this chapter Dickens presents a new character but takes his time and unfolds this person’s appearance and characteristics very slowly. Rather than simply giving us the rider’s name we see Dickens subtlety informing us of the gentleman in two distinct ways. First, let’s notice the gentleman’s speech patterns. What is your initial impression of the man from his manner of speaking to Willet? Second, and I think as telling, is the description of the room that he will occupy. How would you feel if you were ushered into this room? Very often, almost always in fact, the rooms or the buildings that a character occupies in a Dickens provide a framework for the character, their personality, and their place within the arc of the plot. For example, through Sim’s sneaking down the stairs at Varden’s home, and then being ushered into the underground cavern-like rooms where the ‘Prentice Knights meet, the reader gets a broader understanding of Sim’s character. What could we presume about this gentleman by reflecting upon the room Dickens has placed him in?

The gentleman requests a pen, ink, and paper. He is obviously going to write a note. He wants the note to be immediately taken to the Warren. John Willet does not have his reliable son available to deliver the note, but tells the guest that he has someone else who can deliver the note, a person who is “touched and flighty.” Immediately, the guest knows that Willet is referring to Barnaby. But wait a minute! How could a traveller know the name of Barnaby from such a description? What does that suggest? The strange guest then comments that he saw Barnaby in London last evening. The guest seems to know that Barnaby often goes to the Warren. John tells the guest that Barnaby’s father was murdered at the Warren. The guest reply’s he knows that fact. Finally we learn that the guest’s name is Mr Chester. Barnaby is to take the note to Mr Haredale, wait for a response, and bring it back to the Maypole.

Thoughts

We learn that Mr Haredale and Mr Chester have a long and antagonistic history. The messenger is Barnaby. To what extent could this part of the plot be important. For fun, speculate of how it might be important.

Mr Chester awaits Barnaby’s return, which is so slow that Chester decides he will spend the night at the Maypole rather than risk being “knocked on the head” as his son has the night before. As Chester is settling in for the night Barnaby returns with the news that Haredale will be at the Maypole in an hour. Barnaby then bends down and gazes at the smoke from the chimney. Barnaby’s speech about the smoke could be a stream of conscious, or an unfocused ramble or it could be symbolic and offering the reader insight into future events yet to occur. How do you think the reader is to take Barnaby’s seemingly flights of verbal fantasy? I can’t help but keep thinking of the Fool in King Lear. How should a reader go about untangling the words of such characters?

We now have witnessed the first meeting between Haredale and Chester. What are your initial impressions of the pair?

Reflections

The novel is off to a quick start. We have already been introduced to a series of interesting characters. We have two major settings, one being London, and one being the Maypole and the surrounding countryside. Our mysteries are already piling up:

What is the reason or nature of the apparent hostility between Haredale and Chester?

Who is the mysterious person that lurks in the shadows of the first chapters?

For what purpose has Dickens created the ‘Prentice Knights?

It appears that Dickens is creating a series of father-son combinations of characters? What might he be up to with this plot device?

How are we to interpret the character and conversations of Barnaby Rudge?

Much more is to come. Enjoy your week’s reading my friends.

Curiosities

Here is a link that will help explain Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow. It will certainly not be required to understand Jung in our reading of Barnaby Rudge, but since we will come across the mention of shadows and shadowy figures I thought it might be of interest. Carl Jung came after Charles Dickens so Dickens would have been totally unaware of Jung’s ideas. The article does discuss R. L. Stevenson’s Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde. If we go back to Shakespeare we have King Lear’s lament “who is it that can tell me who I am” to which his Fool replies “Lear’s shadow.” Authors have always looked at shadows in interesting ways.

Since we will encounter shadows in Barnaby Rudge I offer this to you.

https://academyofideas.com/2015/12/ca...

Here is a link that will help explain Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow. It will certainly not be required to understand Jung in our reading of Barnaby Rudge, but since we will come across the mention of shadows and shadowy figures I thought it might be of interest. Carl Jung came after Charles Dickens so Dickens would have been totally unaware of Jung’s ideas. The article does discuss R. L. Stevenson’s Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde. If we go back to Shakespeare we have King Lear’s lament “who is it that can tell me who I am” to which his Fool replies “Lear’s shadow.” Authors have always looked at shadows in interesting ways.

Since we will encounter shadows in Barnaby Rudge I offer this to you.

https://academyofideas.com/2015/12/ca...

You've brought up many interesting questions, Peter. I hesitate to attempt answering them, for fear of looking foolish when all of my suppositions turn out to be in error!

You've brought up many interesting questions, Peter. I hesitate to attempt answering them, for fear of looking foolish when all of my suppositions turn out to be in error! (Further comments deleted - I found the passage that Peter alluded to, and which I'd missed in my first reading.)

I haven't read King Lear but I think it's safe to assume that Barnaby will hold the key to solving the mysteries with which we've been presented. After all, Dickens changed the title of the novel to bear Barnaby's name - a pretty major "hint" all by itself!

I haven't read King Lear but I think it's safe to assume that Barnaby will hold the key to solving the mysteries with which we've been presented. After all, Dickens changed the title of the novel to bear Barnaby's name - a pretty major "hint" all by itself! Dickens has been careful to show the reader that those around him think Barnaby's ramblings are nonsense, and that he's considered an "idiot" (which makes me bristle a bit when I read it -- those 21st century sensibilities are hard to suppress sometimes). Barnaby is easily overlooked or ignored, and thought of by his neighbors as rather inconsequential.

But Varden says this to young Edward:

I have watched him oftener than you, and I know, little as you would think it, that he’s listening now.’

And then there's this remark from Barnaby, himself:

I lead a merrier life than you, with all your cleverness. You’re the dull men. We're the bright ones.

These off-hand remarks alert us that Barnaby is observant - even when he doesn't seem to be - and that he may well have some knowledge or information that other, wiser men haven't learned. I think Peter's right, that we must pay close attention as the novel progresses to Barnaby's "ramblings" (and perhaps to those of the mimic Grip, as well).

Peter wrote: "Chapter 6...It is clear that Varden has some suspicions about Mary ..."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 6...It is clear that Varden has some suspicions about Mary ..."Well, who can blame him, after what he just witnessed? I've been trying to figure out how to justify Varden's leaving Mary without demanding more information, particularly in exchange for his silence. I certainly would have demanded to know more under the circumstances. Obviously his acceptance is necessary for literary purposes, but the only way I can overlook it as a reader is to assume that Varden was so startled by what he'd seen and heard that he just wasn't thinking clearly, and that his long friendship with Mary led him to trust her judgment, despite all the red flags that were waving in his face.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 8 - Any group that meets in secret and functions under the belief that they are oppressed needs to be monitored carefully. ..."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 8 - Any group that meets in secret and functions under the belief that they are oppressed needs to be monitored carefully. ..."Amen to that, Peter. I'm still not finding Sim amusing, but he does have his quirks. Not only does he find his own legs an asset, but apparently blind Stagg thinks they're pretty fabulous, too! Only Dickens could get away with this! In the hands of any other author we'd all be thinking, "What the hell...??" But for Dickens, it's just another day. Okay - maybe that part IS kind of entertaining. :-)

I did enjoy Sim's interaction with Miggs. Dickens best be careful, though -- a little of Miggs and Martha might go a loooong way, and he should use them sparingly. The relationship between Gabriel and Martha reminds me a bit of the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice and the Buckets ("It's bouquet!") from "Keeping Up Appearances" - other long-suffering but good-natured husbands dealing with challenging wives. Somehow, inexplicably, there seems to be an underlying love in all three cases.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 8 - Any group that meets in secret and functions under the belief that they are oppressed needs to be monitored carefully. ..."

Amen to that, Peter. I'm still not finding Sim..."

Mary Lou

I really enjoy your comments, observations, and delightful wit that you offer us. Please feel free to respond to any and all questions you would like and don’t worry about any of your observations being accurate or not. Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit are the two novels that I know least about. Many of my questions come from my own need to learn or understand. I’m going to be stumbling along up to Christmas with these two novels.

Dombey and Son, however, is a favourite so I will just cross my fingers and hope I won’t mess up too much until then.

I don’t think I am going to like Sim as a person in the novel but do get the feeling that he will be a favourite to watch as he stumbles and bumbles through the novel. He also seems to have the potential to be a rather nasty bit of business. Also, Dickens seems to be focussed on Sim’s legs. Where will all that lead us?

Amen to that, Peter. I'm still not finding Sim..."

Mary Lou

I really enjoy your comments, observations, and delightful wit that you offer us. Please feel free to respond to any and all questions you would like and don’t worry about any of your observations being accurate or not. Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit are the two novels that I know least about. Many of my questions come from my own need to learn or understand. I’m going to be stumbling along up to Christmas with these two novels.

Dombey and Son, however, is a favourite so I will just cross my fingers and hope I won’t mess up too much until then.

I don’t think I am going to like Sim as a person in the novel but do get the feeling that he will be a favourite to watch as he stumbles and bumbles through the novel. He also seems to have the potential to be a rather nasty bit of business. Also, Dickens seems to be focussed on Sim’s legs. Where will all that lead us?

As I recall, Edgar Allan Poe wrote The Raven after reviewing Barnaby Rudge for a Baltimore newspaper.

As I recall, Edgar Allan Poe wrote The Raven after reviewing Barnaby Rudge for a Baltimore newspaper. I think he gave Rudge high marks, but not sure. I think Poe was also a supporter of Dickens' concerns about copyrights.

John and Curiosities

The link below will tell us more about Dickens and his ravens. I have read The Ravenmaster: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London and it was very enjoyable.

Dickens and Poe did share a common belief that copyright was something to support and strive to enforce. Poe’s “the Raven” may well find part of its inspiration from Dickens.

https://lithub.com/meet-the-beloved-p...

The link below will tell us more about Dickens and his ravens. I have read The Ravenmaster: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London and it was very enjoyable.

Dickens and Poe did share a common belief that copyright was something to support and strive to enforce. Poe’s “the Raven” may well find part of its inspiration from Dickens.

https://lithub.com/meet-the-beloved-p...

Peter wrote: "Chapter 8

Peter wrote: "Chapter 8This chapter will be devoted to Mr Varden’s apprentice named Sim Tappertit. First, we learn that Sim has made a copy of the Varden household’s front door key. Obviously, Sim is not the b..."

I see the character Sim as a sly fox.

(Don’t shew this to Mr. Wakley, if it ever comes to that)

Devonshire Terrace.

Thursday Morning.

My Dear Thompson,

I called to enquire after the bill yesterday, but it was not made out. When I have it, I will not fail to call a settlement of the same.

Maclise and I are raving with love for the Queen – with a hopeless passion whose extent no tongue can tell, nor mind of man conceive. On Tuesday we sallied down to Windsor, prowled about the Castle, saw the corridor and their private rooms – nay, the very bed chamber (which we know from having been there twice) lighted up with such a ruddy, homely, brilliant glow – bespeaking so much bliss and happiness – that I, your humble servant, lay down in the mud at the top of the long walk and refused all comfort – to the immeasurable astonishment of a few straggling passengers who had survived the drunkenness of the previous night. After perpetrating sundry other extravagances we returned home at Midnight in a Post Chaise, and now we wear marriage medals next out hearts and go about with pockets full of portraits which we weep over in secret. Forster was with us at Windsor and (for the joke’s sake) counterfeits a passion too, but he does not love her.

Don’t mention this unhappy attachment. I am very wretched, and think of leaving my home. My wife makes me wretched, miserable, and when I hear the voices of my Infant children, I burst into tears. I fear it is too late to ask you to take this house, now that you have such arrangements of comfort in Pall Mall; but if you will, you shall have it very cheap – furniture at a low valuation – money not being so much an object, as escaping from the family. For God’s sake turn this matter over in your mind, and please to ask Captain Kincaide what he asks – his lowest terms, in short, for ready money – for that Post of Gentleman at Arms. I must be near her, and I see no better way than that, for the present.

I have on hand three Numbers of Master Humphrey’s Clock, and the two first chapters of Barnaby. Would you like to buy them? Writing any more in my present state of mind, is out of the question. They are written in a pretty fair hand and when I am in the Serpentine may be considered curious. Name your own terms.

I know you don’t like trouble, but I have ventured, notwithstanding, to make you an Executor of my will. There won’t be a great deal to do, as there is no money. There is a little bequest having reference to her which you might like to execute. I have heard on the Lord Chamberlain’s authority, that she reads my books and is very fond of them - - I think she will be sorry when I am gone. I should wish to be embalmed, and to be kept (if practicable) on the top of the Triumphal Arch at Buckingham Palace when she is in town, and on the north-east turrets of the Round Tower when she is at Windsor.

From your distracted and blighted friend

C.D.

MssDate: Thursday Morning [13 February 1840]

Media Type: Letters

Source: Rare Book Department

Recipient: Thompson, Thomas James, 1812-1881

Devonshire Terrace.

Thursday Morning.

My Dear Thompson,

I called to enquire after the bill yesterday, but it was not made out. When I have it, I will not fail to call a settlement of the same.

Maclise and I are raving with love for the Queen – with a hopeless passion whose extent no tongue can tell, nor mind of man conceive. On Tuesday we sallied down to Windsor, prowled about the Castle, saw the corridor and their private rooms – nay, the very bed chamber (which we know from having been there twice) lighted up with such a ruddy, homely, brilliant glow – bespeaking so much bliss and happiness – that I, your humble servant, lay down in the mud at the top of the long walk and refused all comfort – to the immeasurable astonishment of a few straggling passengers who had survived the drunkenness of the previous night. After perpetrating sundry other extravagances we returned home at Midnight in a Post Chaise, and now we wear marriage medals next out hearts and go about with pockets full of portraits which we weep over in secret. Forster was with us at Windsor and (for the joke’s sake) counterfeits a passion too, but he does not love her.

Don’t mention this unhappy attachment. I am very wretched, and think of leaving my home. My wife makes me wretched, miserable, and when I hear the voices of my Infant children, I burst into tears. I fear it is too late to ask you to take this house, now that you have such arrangements of comfort in Pall Mall; but if you will, you shall have it very cheap – furniture at a low valuation – money not being so much an object, as escaping from the family. For God’s sake turn this matter over in your mind, and please to ask Captain Kincaide what he asks – his lowest terms, in short, for ready money – for that Post of Gentleman at Arms. I must be near her, and I see no better way than that, for the present.

I have on hand three Numbers of Master Humphrey’s Clock, and the two first chapters of Barnaby. Would you like to buy them? Writing any more in my present state of mind, is out of the question. They are written in a pretty fair hand and when I am in the Serpentine may be considered curious. Name your own terms.

I know you don’t like trouble, but I have ventured, notwithstanding, to make you an Executor of my will. There won’t be a great deal to do, as there is no money. There is a little bequest having reference to her which you might like to execute. I have heard on the Lord Chamberlain’s authority, that she reads my books and is very fond of them - - I think she will be sorry when I am gone. I should wish to be embalmed, and to be kept (if practicable) on the top of the Triumphal Arch at Buckingham Palace when she is in town, and on the north-east turrets of the Round Tower when she is at Windsor.

From your distracted and blighted friend

C.D.

MssDate: Thursday Morning [13 February 1840]

Media Type: Letters

Source: Rare Book Department

Recipient: Thompson, Thomas James, 1812-1881

Kim wrote: "(Don’t shew this to Mr. Wakley, if it ever comes to that)

Devonshire Terrace.

Thursday Morning.

My Dear Thompson,

I called to enquire after the bill yesterday, but it was not made out. When ..."

Kim, what a curious letter. It seems tongue-in-cheek, ironic, serious, and foretelling all at the same time.

Very strange indeed.

Devonshire Terrace.

Thursday Morning.

My Dear Thompson,

I called to enquire after the bill yesterday, but it was not made out. When ..."

Kim, what a curious letter. It seems tongue-in-cheek, ironic, serious, and foretelling all at the same time.

Very strange indeed.

Edward Chester relates his adventures

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

They entered a homely bedchamber, garnished in a scanty way with chairs, whose spindle-shanks bespoke their age, and other furniture of very little worth; but clean and neatly kept. Reclining in an easy-chair before the fire, pale and weak from waste of blood, was Edward Chester, the young gentleman who had been the first to quit the Maypole on the previous night, and who, extending his hand to the locksmith, welcomed him as his preserver and friend.

‘Say no more, sir, say no more,’ said Gabriel. ‘I hope I would have done at least as much for any man in such a strait, and most of all for you, sir. A certain young lady,’ he added, with some hesitation, ‘has done us many a kind turn, and we naturally feel—I hope I give you no offence in saying this, sir?’

The young man smiled and shook his head; at the same time moving in his chair as if in pain.

‘It’s no great matter,’ he said, in answer to the locksmith’s sympathising look, ‘a mere uneasiness arising at least as much from being cooped up here, as from the slight wound I have, or from the loss of blood. Be seated, Mr Varden.’

‘If I may make so bold, Mr Edward, as to lean upon your chair,’ returned the locksmith, accommodating his action to his speech, and bending over him, ‘I’ll stand here for the convenience of speaking low. Barnaby is not in his quietest humour to-night, and at such times talking never does him good.’

They both glanced at the subject of this remark, who had taken a seat on the other side of the fire, and, smiling vacantly, was making puzzles on his fingers with a skein of string.

‘Pray, tell me, sir,’ said Varden, dropping his voice still lower, ‘exactly what happened last night. I have my reason for inquiring. You left the Maypole, alone?’

‘And walked homeward alone, until I had nearly reached the place where you found me, when I heard the gallop of a horse.’

‘Behind you?’ said the locksmith.

‘Indeed, yes—behind me. It was a single rider, who soon overtook me, and checking his horse, inquired the way to London.’

‘You were on the alert, sir, knowing how many highwaymen there are, scouring the roads in all directions?’ said Varden.

‘I was, but I had only a stick, having imprudently left my pistols in their holster-case with the landlord’s son. I directed him as he desired. Before the words had passed my lips, he rode upon me furiously, as if bent on trampling me down beneath his horse’s hoofs. In starting aside, I slipped and fell. You found me with this stab and an ugly bruise or two, and without my purse—in which he found little enough for his pains. And now, Mr Varden,’ he added, shaking the locksmith by the hand, ‘saving the extent of my gratitude to you, you know as much as I.’

‘Except,’ said Gabriel, bending down yet more, and looking cautiously towards their silent neighhour, ‘except in respect of the robber himself. What like was he, sir? Speak low, if you please. Barnaby means no harm, but I have watched him oftener than you, and I know, little as you would think it, that he’s listening now.’

It required a strong confidence in the locksmith’s veracity to lead any one to this belief, for every sense and faculty that Barnaby possessed, seemed to be fixed upon his game, to the exclusion of all other things. Something in the young man’s face expressed this opinion, for Gabriel repeated what he had just said, more earnestly than before, and with another glance towards Barnaby, again asked what like the man was.

‘The night was so dark,’ said Edward, ‘the attack so sudden, and he so wrapped and muffled up, that I can hardly say. It seems that—’

‘Don’t mention his name, sir,’ returned the locksmith, following his look towards Barnaby; ‘I know HE saw him. I want to know what YOU saw.’

‘All I remember is,’ said Edward, ‘that as he checked his horse his hat was blown off. He caught it, and replaced it on his head, which I observed was bound with a dark handkerchief. A stranger entered the Maypole while I was there, whom I had not seen—for I had sat apart for reasons of my own—and when I rose to leave the room and glanced round, he was in the shadow of the chimney and hidden from my sight. But, if he and the robber were two different persons, their voices were strangely and most remarkably alike; for directly the man addressed me in the road, I recognised his speech again.’

‘It is as I feared. The very man was here to-night,’ thought the locksmith, changing colour. ‘What dark history is this!’

‘Halloa!’ cried a hoarse voice in his ear. ‘Halloa, halloa, halloa! Bow wow wow. What’s the matter here! Hal-loa!’

The speaker—who made the locksmith start as if he had been some supernatural agent—was a large raven, who had perched upon the top of the easy-chair, unseen by him and Edward, and listened with a polite attention and a most extraordinary appearance of comprehending every word, to all they had said up to this point; turning his head from one to the other, as if his office were to judge between them, and it were of the very last importance that he should not lose a word.

Barnaby's Dream

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Barnaby,’ said the locksmith, with a grave look; ‘come hither, lad.’

‘I know what you want to say. I know!’ he replied, keeping away from him. ‘But I’m cunning, I’m silent. I only say so much to you—are you ready?’ As he spoke, he caught up the light, and waved it with a wild laugh above his head.

‘Softly—gently,’ said the locksmith, exerting all his influence to keep him calm and quiet. ‘I thought you had been asleep.’

‘So I HAVE been asleep,’ he rejoined, with widely-opened eyes. ‘There have been great faces coming and going—close to my face, and then a mile away—low places to creep through, whether I would or no—high churches to fall down from—strange creatures crowded up together neck and heels, to sit upon the bed—that’s sleep, eh?’

‘Dreams, Barnaby, dreams,’ said the locksmith.

‘Dreams!’ he echoed softly, drawing closer to him. ‘Those are not dreams.’

‘What are,’ replied the locksmith, ‘if they are not?’

‘I dreamed,’ said Barnaby, passing his arm through Varden’s, and peering close into his face as he answered in a whisper, ‘I dreamed just now that something—it was in the shape of a man—followed me—came softly after me—wouldn’t let me be—but was always hiding and crouching, like a cat in dark corners, waiting till I should pass; when it crept out and came softly after me.—Did you ever see me run?’

‘Many a time, you know.’

‘You never saw me run as I did in this dream. Still it came creeping on to worry me. Nearer, nearer, nearer—I ran faster—leaped—sprung out of bed, and to the window—and there, in the street below—but he is waiting for us. Are you coming?’

‘What in the street below, Barnaby?’ said Varden, imagining that he traced some connection between this vision and what had actually occurred.

Barnaby looked into his face, muttered incoherently, waved the light above his head again, laughed, and drawing the locksmith’s arm more tightly through his own, led him up the stairs in silence.

Barnaby and Grip

Chapter 6

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

‘Call him!’ echoed Barnaby, sitting upright upon the floor, and staring vacantly at Gabriel, as he thrust his hair back from his face. ‘But who can make him come! He calls me, and makes me go where he will. He goes on before, and I follow. He’s the master, and I’m the man. Is that the truth, Grip?’

The raven gave a short, comfortable, confidential kind of croak;—a most expressive croak, which seemed to say, ‘You needn’t let these fellows into our secrets. We understand each other. It’s all right.’

‘I make HIM come?’ cried Barnaby, pointing to the bird. ‘Him, who never goes to sleep, or so much as winks!—Why, any time of night, you may see his eyes in my dark room, shining like two sparks. And every night, and all night too, he’s broad awake, talking to himself, thinking what he shall do to-morrow, where we shall go, and what he shall steal, and hide, and bury. I make HIM come! Ha ha ha!’

On second thoughts, the bird appeared disposed to come of himself. After a short survey of the ground, and a few sidelong looks at the ceiling and at everybody present in turn, he fluttered to the floor, and went to Barnaby—not in a hop, or walk, or run, but in a pace like that of a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles. Then, stepping into his extended hand, and condescending to be held out at arm’s length, he gave vent to a succession of sounds, not unlike the drawing of some eight or ten dozen of long corks, and again asserted his brimstone birth and parentage with great distinctness.

The locksmith shook his head—perhaps in some doubt of the creature’s being really nothing but a bird—perhaps in pity for Barnaby, who by this time had him in his arms, and was rolling about, with him, on the ground. As he raised his eyes from the poor fellow he encountered those of his mother, who had entered the room, and was looking on in silence.

Commentary about the artist:

Harry Furniss, son of an English engineer but born in Wexford, having trained and worked as an artist and draughtsman in his native Ireland, in 1873 went to London to look for artistic work. After seven years of free-lance work which included pen-and-ink caricatures published in The Illustrated London News, at the age twenty-six, he began what would become a life-time career as a magazine illustrator when in October 1880 Punch published his parodic drawing of the Temple Bar dragon as his first staff commission. He continued with that magazine for fourteen years, and by his own calculation produced for that celebrated journal of metropolitan humour "over two thousand six hundred designs, from the smallest to the largest (the latter were published in the Christmas numbers, 1890 and 1891)". His series The Essence of Parliament contained caricatures of the leading Whig and Tory politicians of the day, most notably Sir William Gladstone, whom the artist habitually depicted in large collars. An ardent Unionist, he took issue in print and illustrations with the Irish Nationalists in Parliament, satirizing one Nationalist Member of Parliament, Swift MacNeill, as a gorilla.

Hot-tempered, brash, and occasionally mendacious, Furniss could not have been an easy man to work with, and it is not surprising that his visual criticisms of Irish politicians in Punch resulted in threats and even an assault upon his person. Simon Houfe has described his sketches of members from both sides of the House as "sometimes severe, generally humorous, and always well-observed" (The Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, p. 311, as cited in Cohen and Wakeling, p. 104). Furniss also wrote articles, jokes, and dramatic criticism for Punch during his time as a staffer. Moreover, his drawings appeared in The Illustrated London News from 1876 to 1884. In 1894, Furniss left Punch under an artistic cloud after the magazine's publishers discovered that he had sold Pears Soap the copyright to one of his drawings for advertising.

By the time that he struck out on his own to edit and illustrate his own magazine of cartoons and humour, Like Joka in 1894, he had illustrated Lewis Carroll's Sylvie and Bruno (1889) and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893). However, when his magazine failed, he moved to the United States where he joined Thomas Alva Edison in the fledgling film industry from 1912 through 1913, acting in early films, and in 1914 pioneering the first animated cartoon film. His artistic work on Dickens's novels in 1910's The Charles Dickens Library (18 volumes) was the culmination of a life devoted to the novelist, about whom (among other topics) he had lectured all over England. He also illustrated an edition of the works of William Makepeace Thackeray and wrote Confessions of a Caricaturist.

J. A. Hammerton's sixth chapter in The Dickens Picture Book (1910), "The Art of Mr. Harry Furniss," is lavish in its praise of the artist's legion of Dickensian illustrations: "There is certainly no living artist in England or America who could have equaled the achievement of Mr. Furniss". Hammerton credits Furniss as being the equal of the great French illustrator Gustave Doré "in his extraordinary facility of draughtsmanship". The artist's five hundred plates for the 1910 edition of Dickens's works contain over fifty different characters.

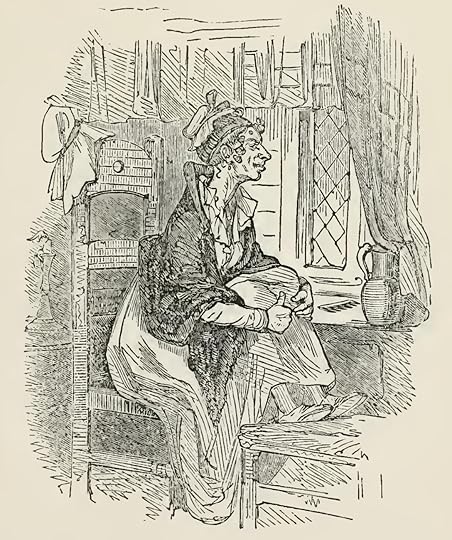

Mrs. Varden goes to bed in a huff

Chapter 7

Thomas Sibson (I think)

Scene in a room, with Mrs Varden leaving, carrying a large book, followed by her maid Miggs at left, carrying a candlestick with burning candle, watched by Simon Tappertit, seated in an armchair at the fireplace at right, scratching his head; small image below showing Simon Tappertit asleep in the armchair, his wig fallen off his head; illustration to Dickens's 'Barnaby Rudge', published in 'Master Humphrey's Clock' and in a volume entitled 'Illustrations to Master Humphrey's Clock' in 1842.

(If you can't see all that, neither can I)

Text Illustrated:

Poor Gabriel twisted his wig about in silence for a long time, and then said mildly, ‘Has Dolly gone to bed?’

‘Your master speaks to you,’ said Mrs Varden, looking sternly over her shoulder at Miss Miggs in waiting.

‘No, my dear, I spoke to you,’ suggested the locksmith.

‘Did you hear me, Miggs?’ cried the obdurate lady, stamping her foot upon the ground. ‘YOU are beginning to despise me now, are you? But this is example!’

At this cruel rebuke, Miggs, whose tears were always ready, for large or small parties, on the shortest notice and the most reasonable terms, fell a crying violently; holding both her hands tight upon her heart meanwhile, as if nothing less would prevent its splitting into small fragments. Mrs Varden, who likewise possessed that faculty in high perfection, wept too, against Miggs; and with such effect that Miggs gave in after a time, and, except for an occasional sob, which seemed to threaten some remote intention of breaking out again, left her mistress in possession of the field. Her superiority being thoroughly asserted, that lady soon desisted likewise, and fell into a quiet melancholy.

The relief was so great, and the fatiguing occurrences of last night so completely overpowered the locksmith, that he nodded in his chair, and would doubtless have slept there all night, but for the voice of Mrs Varden, which, after a pause of some five minutes, awoke him with a start.

‘If I am ever,’ said Mrs V.—not scolding, but in a sort of monotonous remonstrance—‘in spirits, if I am ever cheerful, if I am ever more than usually disposed to be talkative and comfortable, this is the way I am treated.’

‘Such spirits as you was in too, mim, but half an hour ago!’ cried Miggs. ‘I never see such company!’

‘Because,’ said Mrs Varden, ‘because I never interfere or interrupt; because I never question where anybody comes or goes; because my whole mind and soul is bent on saving where I can save, and labouring in this house;—therefore, they try me as they do.’

‘Martha,’ urged the locksmith, endeavouring to look as wakeful as possible, ‘what is it you complain of? I really came home with every wish and desire to be happy. I did, indeed.’

‘What do I complain of!’ retorted his wife. ‘Is it a chilling thing to have one’s husband sulking and falling asleep directly he comes home—to have him freezing all one’s warm-heartedness, and throwing cold water over the fireside? Is it natural, when I know he went out upon a matter in which I am as much interested as anybody can be, that I should wish to know all that has happened, or that he should tell me without my begging and praying him to do it? Is that natural, or is it not?’

‘I am very sorry, Martha,’ said the good-natured locksmith. ‘I was really afraid you were not disposed to talk pleasantly; I’ll tell you everything; I shall only be too glad, my dear.’

‘No, Varden,’ returned his wife, rising with dignity. ‘I dare say—thank you! I’m not a child to be corrected one minute and petted the next—I’m a little too old for that, Varden. Miggs, carry the light.—YOU can be cheerful, Miggs, at least.’

Miggs, who, to this moment, had been in the very depths of compassionate despondency, passed instantly into the liveliest state conceivable, and tossing her head as she glanced towards the locksmith, bore off her mistress and the light together.

‘Now, who would think,’ thought Varden, shrugging his shoulders and drawing his chair nearer to the fire, ‘that that woman could ever be pleasant and agreeable? And yet she can be. Well, well, all of us have our faults. I’ll not be hard upon hers. We have been man and wife too long for that.’

He dozed again—not the less pleasantly, perhaps, for his hearty temper. While his eyes were closed, the door leading to the upper stairs was partially opened; and a head appeared, which, at sight of him, hastily drew back again.

‘I wish,’ murmured Gabriel, waking at the noise, and looking round the room, ‘I wish somebody would marry Miggs. But that’s impossible! I wonder whether there’s any madman alive, who would marry Miggs!’

This was such a vast speculation that he fell into a doze again, and slept until the fire was quite burnt out. At last he roused himself; and having double-locked the street-door according to custom, and put the key in his pocket, went off to bed.

He had not left the room in darkness many minutes, when the head again appeared, and Sim Tappertit entered, bearing in his hand a little lamp.

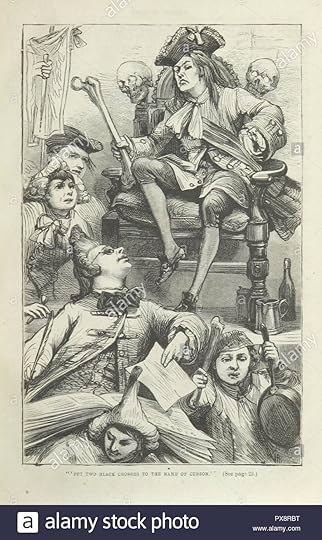

The Secret Society of 'prentice Knights

Chapter 8

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Welcome, noble captain!’ cried a lanky figure, rising as from a nap.

The captain nodded. Then, throwing off his outer coat, he stood composed in all his dignity, and eyed his follower over.

‘What news to-night?’ he asked, when he had looked into his very soul.

‘Nothing particular,’ replied the other, stretching himself—and he was so long already that it was quite alarming to see him do it—‘how come you to be so late?’

‘No matter,’ was all the captain deigned to say in answer. ‘Is the room prepared?’

‘It is,’ replied the follower.

‘The comrade—is he here?’

‘Yes. And a sprinkling of the others—you hear ‘em?’

‘Playing skittles!’ said the captain moodily. ‘Light-hearted revellers!’

There was no doubt respecting the particular amusement in which these heedless spirits were indulging, for even in the close and stifling atmosphere of the vault, the noise sounded like distant thunder. It certainly appeared, at first sight, a singular spot to choose, for that or any other purpose of relaxation, if the other cellars answered to the one in which this brief colloquy took place; for the floors were of sodden earth, the walls and roof of damp bare brick tapestried with the tracks of snails and slugs; the air was sickening, tainted, and offensive. It seemed, from one strong flavour which was uppermost among the various odours of the place, that it had, at no very distant period, been used as a storehouse for cheeses; a circumstance which, while it accounted for the greasy moisture that hung about it, was agreeably suggestive of rats. It was naturally damp besides, and little trees of fungus sprung from every mouldering corner.

The proprietor of this charming retreat, and owner of the ragged head before mentioned—for he wore an old tie-wig as bare and frowzy as a stunted hearth-broom—had by this time joined them; and stood a little apart, rubbing his hands, wagging his hoary bristled chin, and smiling in silence. His eyes were closed; but had they been wide open, it would have been easy to tell, from the attentive expression of the face he turned towards them—pale and unwholesome as might be expected in one of his underground existence—and from a certain anxious raising and quivering of the lids, that he was blind.

‘Even Stagg hath been asleep,’ said the long comrade, nodding towards this person.

‘Sound, captain, sound!’ cried the blind man; ‘what does my noble captain drink—is it brandy, rum, usquebaugh? Is it soaked gunpowder, or blazing oil? Give it a name, heart of oak, and we’d get it for you, if it was wine from a bishop’s cellar, or melted gold from King George’s mint.’

‘See,’ said Mr Tappertit haughtily, ‘that it’s something strong, and comes quick; and so long as you take care of that, you may bring it from the devil’s cellar, if you like.’

‘Boldly said, noble captain!’ rejoined the blind man. ‘Spoken like the ‘Prentices’ Glory. Ha, ha! From the devil’s cellar! A brave joke! The captain joketh. Ha, ha, ha!’

‘I’ll tell you what, my fine feller,’ said Mr Tappertit, eyeing the host over as he walked to a closet, and took out a bottle and glass as carelessly as if he had been in full possession of his sight, ‘if you make that row, you’ll find that the captain’s very far from joking, and so I tell you.’

‘He’s got his eyes on me!’ cried Stagg, stopping short on his way back, and affecting to screen his face with the bottle. ‘I feel ‘em though I can’t see ‘em. Take ‘em off, noble captain. Remove ‘em, for they pierce like gimlets.’

Mr Tappertit smiled grimly at his comrade; and twisting out one more look—a kind of ocular screw—under the influence of which the blind man feigned to undergo great anguish and torture, bade him, in a softened tone, approach, and hold his peace.

‘I obey you, captain,’ cried Stagg, drawing close to him and filling out a bumper without spilling a drop, by reason that he held his little finger at the brim of the glass, and stopped at the instant the liquor touched it, ‘drink, noble governor. Death to all masters, life to all ‘prentices, and love to all fair damsels. Drink, brave general, and warm your gallant heart!’

Mr Tappertit condescended to take the glass from his outstretched hand. Stagg then dropped on one knee, and gently smoothed the calves of his legs, with an air of humble admiration.

‘That I had but eyes!’ he cried, ‘to behold my captain’s symmetrical proportions! That I had but eyes, to look upon these twin invaders of domestic peace!’

‘Get out!’ said Mr Tappertit, glancing downward at his favourite limbs. ‘Go along, will you, Stagg!’

‘When I touch my own afterwards,’ cried the host, smiting them reproachfully, ‘I hate ‘em. Comparatively speaking, they’ve no more shape than wooden legs, beside these models of my noble captain’s.’

‘Yours!’ exclaimed Mr Tappertit. ‘No, I should think not. Don’t talk about those precious old toothpicks in the same breath with mine; that’s rather too much. Here. Take the glass. Benjamin. Lead on. To business!’

With these words, he folded his arms again; and frowning with a sullen majesty, passed with his companion through a little door at the upper end of the cellar, and disappeared; leaving Stagg to his private meditations.

The vault they entered, strewn with sawdust and dimly lighted, was between the outer one from which they had just come, and that in which the skittle-players were diverting themselves; as was manifested by the increased noise and clamour of tongues, which was suddenly stopped, however, and replaced by a dead silence, at a signal from the long comrade. Then, this young gentleman, going to a little cupboard, returned with a thigh-bone, which in former times must have been part and parcel of some individual at least as long as himself, and placed the same in the hands of Mr Tappertit; who, receiving it as a sceptre and staff of authority, cocked his three-cornered hat fiercely on the top of his head, and mounted a large table, whereon a chair of state, cheerfully ornamented with a couple of skulls, was placed ready for his reception.

He had no sooner assumed this position, than another young gentleman appeared, bearing in his arms a huge clasped book, who made him a profound obeisance, and delivering it to the long comrade, advanced to the table, and turning his back upon it, stood there Atlas-wise. Then, the long comrade got upon the table too; and seating himself in a lower chair than Mr Tappertit’s, with much state and ceremony, placed the large book on the shoulders of their mute companion as deliberately as if he had been a wooden desk, and prepared to make entries therein with a pen of corresponding size.

‘This,’ said Mr Tappert gravely, ‘is a flagrant case. Put two black crosses to the name of Curzon.’

Chapter 8

D. H. Friston

Text Illustrated:

When the long comrade had made these preparations, he looked towards Mr Tappertit; and Mr Tappertit, flourishing the bone, knocked nine times therewith upon one of the skulls. At the ninth stroke, a third young gentleman emerged from the door leading to the skittle ground, and bowing low, awaited his commands.

‘Prentice!’ said the mighty captain, ‘who waits without?’

The ‘prentice made answer that a stranger was in attendance, who claimed admission into that secret society of ‘Prentice Knights, and a free participation in their rights, privileges, and immunities. Thereupon Mr Tappertit flourished the bone again, and giving the other skull a prodigious rap on the nose, exclaimed ‘Admit him!’ At these dread words the ‘prentice bowed once more, and so withdrew as he had come.

There soon appeared at the same door, two other ‘prentices, having between them a third, whose eyes were bandaged, and who was attired in a bag-wig, and a broad-skirted coat, trimmed with tarnished lace; and who was girded with a sword, in compliance with the laws of the Institution regulating the introduction of candidates, which required them to assume this courtly dress, and kept it constantly in lavender, for their convenience. One of the conductors of this novice held a rusty blunderbuss pointed towards his ear, and the other a very ancient sabre, with which he carved imaginary offenders as he came along in a sanguinary and anatomical manner.

As this silent group advanced, Mr Tappertit fixed his hat upon his head. The novice then laid his hand upon his breast and bent before him. When he had humbled himself sufficiently, the captain ordered the bandage to be removed, and proceeded to eye him over.

‘Ha!’ said the captain, thoughtfully, when he had concluded this ordeal. ‘Proceed.’

The long comrade read aloud as follows:—‘Mark Gilbert. Age, nineteen. Bound to Thomas Curzon, hosier, Golden Fleece, Aldgate. Loves Curzon’s daughter. Cannot say that Curzon’s daughter loves him. Should think it probable. Curzon pulled his ears last Tuesday week.’

‘How!’ cried the captain, starting.

‘For looking at his daughter, please you,’ said the novice.

‘Write Curzon down, Denounced,’ said the captain. ‘Put a black cross against the name of Curzon.’

‘So please you,’ said the novice, ‘that’s not the worst—he calls his ‘prentice idle dog, and stops his beer unless he works to his liking. He gives Dutch cheese, too, eating Cheshire, sir, himself; and Sundays out, are only once a month.’

‘This,’ said Mr Tappert gravely, ‘is a flagrant case. Put two black crosses to the name of Curzon.’

‘If the society,’ said the novice, who was an ill-looking, one-sided, shambling lad, with sunken eyes set close together in his head—‘if the society would burn his house down—for he’s not insured—or beat him as he comes home from his club at night, or help me to carry off his daughter, and marry her at the Fleet, whether she gave consent or no—’

Mr Tappertit waved his grizzly truncheon as an admonition to him not to interrupt, and ordered three black crosses to the name of Curzon.

‘Which means,’ he said in gracious explanation, ‘vengeance, complete and terrible. ‘Prentice, do you love the Constitution?’

To which the novice (being to that end instructed by his attendant sponsors) replied ‘I do!’

‘The Church, the State, and everything established—but the masters?’ quoth the captain.

Again the novice said ‘I do.’

Miggs in the sanctity of her chamber

Chapter 9

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘I don’t go to bed this night!’ said Miggs, wrapping herself in a shawl, and drawing a couple of chairs near the window, flouncing down upon one, and putting her feet upon the other, ‘till you come home, my lad. I wouldn’t,’ said Miggs viciously, ‘no, not for five-and-forty pound!’

With that, and with an expression of face in which a great number of opposite ingredients, such as mischief, cunning, malice, triumph, and patient expectation, were all mixed up together in a kind of physiognomical punch, Miss Miggs composed herself to wait and listen, like some fair ogress who had set a trap and was watching for a nibble from a plump young traveller.

She sat there, with perfect composure, all night. At length, just upon break of day, there was a footstep in the street, and presently she could hear Mr Tappertit stop at the door. Then she could make out that he tried his key—that he was blowing into it—that he knocked it on the nearest post to beat the dust out—that he took it under a lamp to look at it—that he poked bits of stick into the lock to clear it—that he peeped into the keyhole, first with one eye, and then with the other—that he tried the key again—that he couldn’t turn it, and what was worse, couldn’t get it out—that he bent it—that then it was much less disposed to come out than before—that he gave it a mighty twist and a great pull, and then it came out so suddenly that he staggered backwards—that he kicked the door—that he shook it—finally, that he smote his forehead, and sat down on the step in despair.

When this crisis had arrived, Miss Miggs, affecting to be exhausted with terror, and to cling to the window-sill for support, put out her nightcap, and demanded in a faint voice who was there.

Mr Tappertit cried ‘Hush!’ and, backing to the road, exhorted her in frenzied pantomime to secrecy and silence.

‘Tell me one thing,’ said Miggs. ‘Is it thieves?’

‘No—no—no!’ cried Mr Tappertit.

‘Then,’ said Miggs, more faintly than before, ‘it’s fire. Where is it, sir? It’s near this room, I know. I’ve a good conscience, sir, and would much rather die than go down a ladder. All I wish is, respecting my love to my married sister, Golden Lion Court, number twenty-sivin, second bell-handle on the right-hand door-post.’

‘Miggs!’ cried Mr Tappertit, ‘don’t you know me? Sim, you know—Sim—’

The best apartment at the Maypole

Chapter 10

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

It was spacious enough in all conscience, occupying the whole depth of the house, and having at either end a great bay window, as large as many modern rooms; in which some few panes of stained glass, emblazoned with fragments of armorial bearings, though cracked, and patched, and shattered, yet remained; attesting, by their presence, that the former owner had made the very light subservient to his state, and pressed the sun itself into his list of flatterers; bidding it, when it shone into his chamber, reflect the badges of his ancient family, and take new hues and colours from their pride.

But those were old days, and now every little ray came and went as it would; telling the plain, bare, searching truth. Although the best room of the inn, it had the melancholy aspect of grandeur in decay, and was much too vast for comfort. Rich rustling hangings, waving on the walls; and, better far, the rustling of youth and beauty’s dress; the light of women’s eyes, outshining the tapers and their own rich jewels; the sound of gentle tongues, and music, and the tread of maiden feet, had once been there, and filled it with delight. But they were gone, and with them all its gladness. It was no longer a home; children were never born and bred there; the fireside had become mercenary—a something to be bought and sold—a very courtezan: let who would die, or sit beside, or leave it, it was still the same—it missed nobody, cared for nobody, had equal warmth and smiles for all. God help the man whose heart ever changes with the world, as an old mansion when it becomes an inn!

No effort had been made to furnish this chilly waste, but before the broad chimney a colony of chairs and tables had been planted on a square of carpet, flanked by a ghostly screen, enriched with figures, grinning and grotesque. After lighting with his own hands the faggots which were heaped upon the hearth, old John withdrew to hold grave council with his cook, touching the stranger’s entertainment; while the guest himself, seeing small comfort in the yet unkindled wood, opened a lattice in the distant window, and basked in a sickly gleam of cold March sun.

Leaving the window now and then, to rake the crackling logs together, or pace the echoing room from end to end, he closed it when the fire was quite burnt up, and having wheeled the easiest chair into the warmest corner, summoned John Willet.

Kim wrote: "Edward Chester relates his adventures

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

They entered a homely bedchamber, garnished in a scanty way with chairs, whose spindle-shanks bespoke their age, and other..."

Thank you Kim for posting these illustrations. We read from the first that the events are, as Varden notes “a dark history.” Dickens does keep us in suspense In this week’s chapters. I get the feeling, however, that the locksmith has a very good idea who perpetrated the assault.

And now, a confession. Browne’s illustration of “Barnaby’s Dream” leaves me cold. It is just too, well, un-Phiz like. The letterpress was great, and we certainly get the tension between Varden and Barnaby, but the illustration just didn’t work for me. I can’t believe I just wrote the last sentence.

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

They entered a homely bedchamber, garnished in a scanty way with chairs, whose spindle-shanks bespoke their age, and other..."

Thank you Kim for posting these illustrations. We read from the first that the events are, as Varden notes “a dark history.” Dickens does keep us in suspense In this week’s chapters. I get the feeling, however, that the locksmith has a very good idea who perpetrated the assault.