The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

Martin Chuzzlewit Chapters 4-5

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 5

This chapter’s epigraph tells us we will meet another character with the name Martin Chuzzlewit, but he is a much younger man than the sickly gentleman we met in the previous chapter. They are, as you can imagine, related, but we are getting ahead of ourselves. For now, let’s learn more about Tom Pinch, the long suffering and under-appreciated pupil of Mr Pecksniff.

We begin the chapter with Tom setting out to pick up Mr Pecksniff’s newest pupil in Salisbury. We are told that the horse and the vehicle Tom takes are like their owner Mr Pecksniff, and so both are less than perfect. Tom is proud of the task he has been given. As we read on we watch as Dickens builds the character of Tom Pinch with such phrases as “who could repress a smile - of love for thee, Tom Pinch, and not in jest at thy expense.” After Dickens’s condemnation of the various relatives of Chuzzlewit senior in our previous chapter, here we see Dickens beginning to create a balance of good characters to offset the earlier Slyme and company. It is a delightful day for a ride, and Dickens creates a wonderful winter’s day with “vigorous air,” with the snow and frost like a “dust of diamonds.” Such surroundings make Tom happy and Dickens continues to build the character of Tom by mentioning that the toll-man’s children are happy to see him and even their gruff father is pleased to see him. As he continues his way all who see him are merry and laughed and even kissed their hands as Tom passed. There is a remarkable change in tone in this chapter.

As Tom continues his way towards Salisbury he comes across a man who has a “whimsical face and a very merry pair of blue eyes.” His name is Mark Tapley. Mark joins Tom and they both proceed towards Salisbury. We learn that Mark is an eternal optimist. He refuses to be miserable. Mark did work at the Blue Dragon but only found happiness there. It is Mark’s intention to find credit by being in a place or with someone who needs to be cheered up. To Mark, there is credit in bringing joy and optimism, not being in a place where such emotions already exist. We also learn that most people in and around the Blue Dragon thought that Mark and Mrs Lupin would marry, but to Mark, that would make everyone happy who were already happy, and Mark wants to find a place in the world to make people happy who are not already happy. This may seem to be a rather strange logic for one to have, but Dickens revels in providing his readers with interesting characters. Structurally, here is a second character that is the opposite to the characters we encountered in the previous chapter.

Mark thinks being a gravedigger would be “a good damp, wormy sort of business” where people might need cheering up. He also thinks undertakers, or jailers, or a broker’s man in a poor neighbourhood might benefit from his presence.

Tom Pinch finds Salisbury to be an interesting and bustling place compared to the rural world of the Blue Dragon. Salisbury is a place that Tom knows he cannot encounter from his narrow shelf and bed in Pecksniff’s home. Pinch especially lingers at a bookshop that has a copy of Robinson Crusoe and other books that promise enchantment and escape from the world of Pecksniff. We learn that Tom is an accomplished organist and in playing music he is able to ascend from his present dreary life. Later in the evening Tom finally meets the new Pecksniffian pupil Martin Chuzzlewit who is well dressed, well mannered, and friendly. They become friends immediately.

Tom and Martin leave Salisbury and on their way home stop to give the horse some water and Martin pays for a glass of punch which Dickens points out was a “generous” action. As they pass a church Tom comments that it has a wonderful organ and when he was playing it recently “one of the loveliest and most beautiful faces” appeared at the church to listen and then returned on several occasions after. Tom laments the fact that she has now left the area. Tom and Martin arrive at Pecksniff’s early and find him apparently hard at work over some diagrams. Pecksniff pays Tom a hollow compliment and it humbles Tom. Poor Pinch. He has no self-worth, and Pecksniff has no shame at being such a hypocrite. Pecksniff gives Martin a tour of the house and we learn that Martin and Tom will be sharing a room.

Martin quickly makes friends with Mercy and Charity and they are quite happy to enjoy his attentions and ignore Tom. Pecksniff tells Martin that Tom is “not gifted” and if Tom should forget his place Martin should feel free to put him in his place. And so the evening comes to its close with Pecksniff thinking deeply about what I would guess is how to leverage Martin Chuzzlewit junior to his advantage with Martin Chuzzlewit senior.

Thoughts

Did you notice how this chapter presented three characters in a good light? Tom, Martin Chuzzlewit junior, and Mark Tapley form a good counterbalance to the greedy and avaricious characters of the previous chapter. Why might Dickens have decided to employ this style so early in the novel?

Tom Pinch talks about a beautiful young lady who would slip into the church and listen to him playing the organ. We are told that she has left the village. Who do you think this young lady is? How could she be incorporated into the novel in the future?

Mark Tapley is a curiously cheerful person who seems to almost go in search of problems or sadness in life. How might he be employed later in the novel?

What indications from this chapter do we have that furthers our opinion of Pecksniff and his daughters?

Reflections

This week’s chapters were lengthy, as were the first three chapters of the novel. Our approach to such lengthy chapters may require some adjustment in approach as well. To compensate for this, you will have noticed that we are covering fewer chapters per week than in previous novels. We are in the early stages of the novel but have already been introduced to many characters. So far they seem to break down into the greedy family hangers-on who fluttered like moths to the possible death bed-side of Martin Chuzzlewit senior, and the kindly and innocent characters who are acting as counter weights. These good characters are all young and apparently without much money.

Money, greed, and family disunity appear as possible ongoing tropes in the early chapters. Dickens has introduced through the mention of the novel Robinson Crusoe and other children’s books a possible alternate world to that of Pecksniff and his hypocritical nature. This world of escape and adventure seemed to be tagged to Tom Pinch. Unlike the novel Barnaby Rudge where many of us questioned why the novel was titled as such we have in this novel two Martin Chuzzlewit’s so I feel confident that we will find that the title of this novel will more accurately reflect the characters within the novel.

We shall see.

This chapter’s epigraph tells us we will meet another character with the name Martin Chuzzlewit, but he is a much younger man than the sickly gentleman we met in the previous chapter. They are, as you can imagine, related, but we are getting ahead of ourselves. For now, let’s learn more about Tom Pinch, the long suffering and under-appreciated pupil of Mr Pecksniff.

We begin the chapter with Tom setting out to pick up Mr Pecksniff’s newest pupil in Salisbury. We are told that the horse and the vehicle Tom takes are like their owner Mr Pecksniff, and so both are less than perfect. Tom is proud of the task he has been given. As we read on we watch as Dickens builds the character of Tom Pinch with such phrases as “who could repress a smile - of love for thee, Tom Pinch, and not in jest at thy expense.” After Dickens’s condemnation of the various relatives of Chuzzlewit senior in our previous chapter, here we see Dickens beginning to create a balance of good characters to offset the earlier Slyme and company. It is a delightful day for a ride, and Dickens creates a wonderful winter’s day with “vigorous air,” with the snow and frost like a “dust of diamonds.” Such surroundings make Tom happy and Dickens continues to build the character of Tom by mentioning that the toll-man’s children are happy to see him and even their gruff father is pleased to see him. As he continues his way all who see him are merry and laughed and even kissed their hands as Tom passed. There is a remarkable change in tone in this chapter.

As Tom continues his way towards Salisbury he comes across a man who has a “whimsical face and a very merry pair of blue eyes.” His name is Mark Tapley. Mark joins Tom and they both proceed towards Salisbury. We learn that Mark is an eternal optimist. He refuses to be miserable. Mark did work at the Blue Dragon but only found happiness there. It is Mark’s intention to find credit by being in a place or with someone who needs to be cheered up. To Mark, there is credit in bringing joy and optimism, not being in a place where such emotions already exist. We also learn that most people in and around the Blue Dragon thought that Mark and Mrs Lupin would marry, but to Mark, that would make everyone happy who were already happy, and Mark wants to find a place in the world to make people happy who are not already happy. This may seem to be a rather strange logic for one to have, but Dickens revels in providing his readers with interesting characters. Structurally, here is a second character that is the opposite to the characters we encountered in the previous chapter.

Mark thinks being a gravedigger would be “a good damp, wormy sort of business” where people might need cheering up. He also thinks undertakers, or jailers, or a broker’s man in a poor neighbourhood might benefit from his presence.

Tom Pinch finds Salisbury to be an interesting and bustling place compared to the rural world of the Blue Dragon. Salisbury is a place that Tom knows he cannot encounter from his narrow shelf and bed in Pecksniff’s home. Pinch especially lingers at a bookshop that has a copy of Robinson Crusoe and other books that promise enchantment and escape from the world of Pecksniff. We learn that Tom is an accomplished organist and in playing music he is able to ascend from his present dreary life. Later in the evening Tom finally meets the new Pecksniffian pupil Martin Chuzzlewit who is well dressed, well mannered, and friendly. They become friends immediately.

Tom and Martin leave Salisbury and on their way home stop to give the horse some water and Martin pays for a glass of punch which Dickens points out was a “generous” action. As they pass a church Tom comments that it has a wonderful organ and when he was playing it recently “one of the loveliest and most beautiful faces” appeared at the church to listen and then returned on several occasions after. Tom laments the fact that she has now left the area. Tom and Martin arrive at Pecksniff’s early and find him apparently hard at work over some diagrams. Pecksniff pays Tom a hollow compliment and it humbles Tom. Poor Pinch. He has no self-worth, and Pecksniff has no shame at being such a hypocrite. Pecksniff gives Martin a tour of the house and we learn that Martin and Tom will be sharing a room.

Martin quickly makes friends with Mercy and Charity and they are quite happy to enjoy his attentions and ignore Tom. Pecksniff tells Martin that Tom is “not gifted” and if Tom should forget his place Martin should feel free to put him in his place. And so the evening comes to its close with Pecksniff thinking deeply about what I would guess is how to leverage Martin Chuzzlewit junior to his advantage with Martin Chuzzlewit senior.

Thoughts

Did you notice how this chapter presented three characters in a good light? Tom, Martin Chuzzlewit junior, and Mark Tapley form a good counterbalance to the greedy and avaricious characters of the previous chapter. Why might Dickens have decided to employ this style so early in the novel?

Tom Pinch talks about a beautiful young lady who would slip into the church and listen to him playing the organ. We are told that she has left the village. Who do you think this young lady is? How could she be incorporated into the novel in the future?

Mark Tapley is a curiously cheerful person who seems to almost go in search of problems or sadness in life. How might he be employed later in the novel?

What indications from this chapter do we have that furthers our opinion of Pecksniff and his daughters?

Reflections

This week’s chapters were lengthy, as were the first three chapters of the novel. Our approach to such lengthy chapters may require some adjustment in approach as well. To compensate for this, you will have noticed that we are covering fewer chapters per week than in previous novels. We are in the early stages of the novel but have already been introduced to many characters. So far they seem to break down into the greedy family hangers-on who fluttered like moths to the possible death bed-side of Martin Chuzzlewit senior, and the kindly and innocent characters who are acting as counter weights. These good characters are all young and apparently without much money.

Money, greed, and family disunity appear as possible ongoing tropes in the early chapters. Dickens has introduced through the mention of the novel Robinson Crusoe and other children’s books a possible alternate world to that of Pecksniff and his hypocritical nature. This world of escape and adventure seemed to be tagged to Tom Pinch. Unlike the novel Barnaby Rudge where many of us questioned why the novel was titled as such we have in this novel two Martin Chuzzlewit’s so I feel confident that we will find that the title of this novel will more accurately reflect the characters within the novel.

We shall see.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 4..."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 4..."I have a feeling that some of our Curiosities might have read this (very long!) chapter and be about ready to give up and try again when Dombey rolls around. I would urge you to stick with us! The first time I read Chuzzlewit I actually put a notebook next to my bed and tried to jot down a Chuzzlewit family tree because I was so overwhelmed with all these relatives. I learned over the course of the novel that most of them are not integral to the story. Just know that Martin Chuzzlewit (like Miss Havisham) has a lot of greedy relatives who'd like his money, and poor Mary is a target. As the novel progresses, the characters you'll need to remember will emerge. As you might guess, Tigg and Slyme will play a more significant part as time goes on than the various in-laws and cousins (the Pecksniffs excepted).

I was delighted to see that we were reading fewer chapters for this novel, not remembering that these chapters are so very long! As such, I've only gotten through ch. 4, and will hope to get to chapter 5 before the new week gets underway.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 5 ... There is a remarkable change in tone in this chapter."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 5 ... There is a remarkable change in tone in this chapter."This is the Dickens I love! I know that life's balance requires both darkness and light, and Dickens is a master at both. But nothing makes me happier than these lovely scenes where good people interact and enjoy one another's company.

Tom Pinch sees every stranger as a friend he hasn't met yet. And even once he knows them, he chooses to see the best in them. Just as it was said about Barnaby Rudge, who's really the fool? Tom is happy and optimistic. Would it he be better off if he were less naive? As the wonderful Jean Arthur said as Saunders in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, "I wonder if it isn't a curse to go through life wised-up."

Mark is an odd bird! One wonders to what depths he'll sink in order to find misery enough to make worthy his jollity. I'm afraid we just may find out. I hope he never loses his optimistic outlook.

As for Martin... well, he, too, seems like a good bloke. We must wonder why on Earth he and his grandfather are estranged, when he seems like such a decent sort! The only hint I can find is this parenthetical remark:

Martin (who was very generous with his money) ordered another glass of punch, which they drank between them...

Perhaps Grandpa thinks Martin is irresponsible and wasteful? But, my goodness -- they're splitting the glass of punch! How wasteful can he be, when he isn't even getting them each their own glass?

Mr. Pecksniff had clearly not expected them for hours to come

Despite the sarcasm that runs through my veins, sometimes I find it hard to recognize it in Dickens. When he talks about the Pecksniffs not being prepared for Martin's arrival, is he being facetious? I think he must be, and that the Pecksniffs are feigning their studious and charitable pursuits. Sometimes I think I read things literally that are not meant to be so, and I can see how it might make Dickens a challenge for those who aren't aware of his tongue-in-cheek humor, or who don't speak sarcasm as a second language. That said, the Pecksniffs seem to be so good at faking their goodness, one wonders why they don't just give up the facade and actually BE good. Seems like it would require less energy. As it is though, obviously I must remember as we go along that the narrator is not to be trusted!

The only girl we've met so far that Tom doesn't know is Mary. Could she be the lurker who listened as he played the organ?

Despite their different personalities, I just can't keep Merry and Cherry straight. If anyone has a mnemonic that might help me remember which one is which, I'd appreciate it.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 5 ... There is a remarkable change in tone in this chapter."

This is the Dickens I love! I know that life's balance requires both darkness and light, and Dickens is a master ..."

Hi Mary Lou

I am still struggling to work out how to take Pecksniff. I know he is a false, self-serving, and constantly posing and plotting man but I still can’t entirely come to terms with his personality.

Yes. Three cheers for the good guys in this chapter. I found it interesting how Dickens presented our first impression of Mark Tapley. Just imagine leaving a place where he was happy in order to find a place of sadness. Only Dickens.

This is the Dickens I love! I know that life's balance requires both darkness and light, and Dickens is a master ..."

Hi Mary Lou

I am still struggling to work out how to take Pecksniff. I know he is a false, self-serving, and constantly posing and plotting man but I still can’t entirely come to terms with his personality.

Yes. Three cheers for the good guys in this chapter. I found it interesting how Dickens presented our first impression of Mark Tapley. Just imagine leaving a place where he was happy in order to find a place of sadness. Only Dickens.

I made it through chapter four, remembering I did not have to remember who's who exactly to enjoy the image of a family acting like that. I believe we will indeed see more of Chevvy Slyme and his friend, just as Anthony Chuzzlewit and his son - who have been given first names, unlike the rest of the family, if I recall correctly. I had an enormous cold and some short nights last week, so I feel like I missed quite a bit. I did write things down though! Like 'Pecksniff trying to listen to words that are not meant for his ears, making nothing of it and still doing it. The banging of heads was funny!' I wondered already how it would come back that Slyme is always around the corner.

Chapter 5: off course Tom Pinch is the one who leaves early to pick up Martin Jr., while Pecksniff doesn't even come out of bed yet. It was so wholesome to see Pinch enjoying his ride and Salisbury, and how the people liked him and he them! I agree with Mary Lou, this is the Dickens I love most of all, the counterbalance to the dark and dreary. I read this book once, about a year and a half ago, but I hardly remember this chapter, or much about the book at all for that matter. Shame on me! I believe Mark Tapley will indeed go a long way to find a place of sadness, but I am glad he will. We all need a Mark Tapley in our lives sometimes.

I did wonder at Martin Jr. On one hand, he seems like a nice fellow, orders punch, and is chatting away befriending Tom. On the other hand, he seemed to be a bit ... materialistic might not be the best word, but I'm still looking for a better one. It was a combination of small things: the one glass of punch had to be shared between them, and when Tom told that he did not gain any monetary reward for playing the organ, Martin remarks 'he is the strangest fellow' for doing something without getting something in return. I wonder how much of his granddad rubbed off on him.

I did wonder at Martin Jr. On one hand, he seems like a nice fellow, orders punch, and is chatting away befriending Tom. On the other hand, he seemed to be a bit ... materialistic might not be the best word, but I'm still looking for a better one. It was a combination of small things: the one glass of punch had to be shared between them, and when Tom told that he did not gain any monetary reward for playing the organ, Martin remarks 'he is the strangest fellow' for doing something without getting something in return. I wonder how much of his granddad rubbed off on him.

Jantine wrote: "Chapter 5: off course Tom Pinch is the one who leaves early to pick up Martin Jr., while Pecksniff doesn't even come out of bed yet. It was so wholesome to see Pinch enjoying his ride and Salisbury..."

Hi Jantine

Your phrase concerning Mark Tapley that he will go a long way to find a place of sadness was a perfect way to sum up his character. It will be interesting to see how Dickens will develop his character and how or if he will be able to effect change because of his unique way at looking at life.

Hi Jantine

Your phrase concerning Mark Tapley that he will go a long way to find a place of sadness was a perfect way to sum up his character. It will be interesting to see how Dickens will develop his character and how or if he will be able to effect change because of his unique way at looking at life.

Chapter 4

Chapter 4Good Grief! What a family. Cockroaches.

No wonder Martin won't leave anything to Mary. Look what he'd be doing to her! And I now forgive him for his horrible outlook on life.

I think chapter 1 provides context and background for everything that follows. Is this a disposition on family?

Too bad Mr Tigg isn't paid for talking. A penny a word, and he'd be buried in such riches he could take care of the whole family.

Love those descriptions of the family. The one with pimples and the cravat is hilarious.

Slyme? Slyme!

May I close with another Good Grief!!

Peter wrote: "Could there be any significance in the fact that they appear to know each other, or are related to each other in some way?"

Peter wrote: "Could there be any significance in the fact that they appear to know each other, or are related to each other in some way?"They are all related; the town, Mrs. Lupin, Martin, and Mary are besieged. Again, back to chapter 1: this is a Guy Fawkes family.

The whole chapter is hilarious. Who can blame Martin and Mary for leaving while the others plot? This is probably how we end in the U.S. The U.S. was a good place to hide.

Henry James was another author who weaved money and its effects on people into his stories.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 4..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 4..."I have a feeling that some of our Curiosities might have read this (very long!) chapter and be about ready to give up and try again when Dombey rolls around. I would ur..."

I'm thoroughly enjoying this read. Best so far. I love when the Dickens' narrator doesn't hold back.

Dickens could have divided chapter 4 into two, though, the family meeting constituting the second chapter.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 4

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 4Good Grief! What a family. Cockroaches.

No wonder Martin won't leave anything to Mary. Look what he'd be doing to her! And I now forgive him for his horrible outlook on life.

I think ..."

I too find myself more sympathetic to Martin Sr. the more time I spend with his relatives. :)

Peter wrote: "We are in the beginning chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit. Of all his novels, this one gives me the most trouble...."

Peter wrote: "We are in the beginning chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit. Of all his novels, this one gives me the most trouble...."Yes, I'm having trouble here. I'm not so sure the problem is MC though so much as that after--is it five novels in a row? six?--I find I am starting to feel about Dickens the way you feel about a relative who has stayed to visit too long. I still love and admire and own him, but I find his irritating habits are getting on my nerves. I'm also considering skipping Chuzzlewit because I keep hearing how good Dombey is and I've never read it, and I'd kind of like to approach it fresh.

For now, I'm just going to skim some, mostly the parts about Pecksniff and Pinch, who are grating on me because they appear to be respectively irredeemably evil and incorruptibly good, and I feel that point has been sufficiently made and I don't really want to hear about it anymore.

I did enjoy Mark Tapley and I find I am also developing a fondness for petty, unpleasant people who lash out at other petty, unpleasant people, as in Barnaby Rudge where(view spoiler), or in this book where Mr. George spars with the strong-minded woman. I feel a little guilty about enjoying this kind of ugliness but I really do prefer the human vulnerability of characters like this to the Tom Pinches.

Julie wrote: "Yes, I'm having trouble here. I'm not so sure the problem is MC though so much as that after--is it five novels in a row? six?--I find I am starting to feel about Dickens the way you feel about a relative who has stayed to visit too long"

Julie wrote: "Yes, I'm having trouble here. I'm not so sure the problem is MC though so much as that after--is it five novels in a row? six?--I find I am starting to feel about Dickens the way you feel about a relative who has stayed to visit too long"This is why I opted out of Barnaby Rudge. It was a good move. I'm enjoying MC, while I was dragging the last third of TOCS.

Jantine wrote: "I did wonder at Martin Jr. On one hand, he seems like a nice fellow, orders punch, and is chatting away befriending Tom. On the other hand, he seemed to be a bit ... materialistic might not be the best word, but I'm still looking for a better one. It was a combination of small things: the one glass of punch had to be shared between them, and when Tom told that he did not gain any monetary reward for playing the organ, Martin remarks 'he is the strangest fellow' for doing something without getting something in return. I wonder how much of his granddad rubbed off on him."

Jantine wrote: "I did wonder at Martin Jr. On one hand, he seems like a nice fellow, orders punch, and is chatting away befriending Tom. On the other hand, he seemed to be a bit ... materialistic might not be the best word, but I'm still looking for a better one. It was a combination of small things: the one glass of punch had to be shared between them, and when Tom told that he did not gain any monetary reward for playing the organ, Martin remarks 'he is the strangest fellow' for doing something without getting something in return. I wonder how much of his granddad rubbed off on him."I'm with you, Jantine! Martin comes across to me as, at this stage, pretty selfish and maybe a little manipulative.

We see him take advantage of Tom Pinch repeatedly. First, when he doesn't recognize him, he hogs the fire, and notice his reaction when he does realize who Pinch is: "And I have been keeping the fire from you all this while! I had no idea you were Mr Pinch.... Pray excuse me. How do you do? Oh, do draw nearer, pray!" So Martin's happy to hog the heat to himself until he has someone he needs to impress: it's not a problem to leave a stranger in a thin coat to be cold.

Then he mentions he would have ordered a drink but "I didn't like to run the chance of being found drinking it, without knowing what kind of person you were"--but once he takes (pretty intelligently) Pinch's measure, and realizes he can get away with anything and Pinch won't mind, he immediately starts drinking away and then takes advantage of him again. He lets Tom drive so he, Martin, doesn't have to get his fingers cold; and then he stows his case so that Tom is forced "into such an awkward position, that he had much ado to see anything but his own knees. But it is an ill wind that blows nobody any good... for the cold air came from Mr Pinch's side of the carriage, and by interposing a perfect wall of box and man between it and the new pupil, he shielded that young gentleman effectually..."

So yes, Martin while not utterly evil is not above taking what good can come his way at the expense of others. But I do think he's likely to become self-conscious of his own flaws and maybe improve, and this I think will be fun to watch.

Julie wrote: "I'm with you, Jantine! Martin comes across to me as, at this stage, pretty selfish and maybe a little manipulative. .."

Julie wrote: "I'm with you, Jantine! Martin comes across to me as, at this stage, pretty selfish and maybe a little manipulative. .."You, Jantine, and Xan picked up on something that I subconsciously chose to overlook. I wanted to think of Martin as a good person, and chose to see only his likability and not the red flags. I still don't think he's "utterly evil" either, but maybe he's not the stand-up guy I thought he was.

Mary Lou wrote: "Julie wrote: "I'm with you, Jantine! Martin comes across to me as, at this stage, pretty selfish and maybe a little manipulative. .."

Mary Lou wrote: "Julie wrote: "I'm with you, Jantine! Martin comes across to me as, at this stage, pretty selfish and maybe a little manipulative. .."You, Jantine, and Xan picked up on something that I subconscio..."

This is why I enjoy these discussions. I did notice all these little selfish actions by the younger Martin but did not really put them all together until Jantine and Julie did so. Yes, he does seem like such a nice guy until you notice that he is taking all the good things for himself.

It is also interesting that Pecksniff doesn't want Pinch to mention his grandfather to Martin, Jr. Does he not know that his grandfather is ill and certainly it seems he does not know that he was in town recently and Pecksniff had contact with him? I wonder if they are truly estranged or just not in close contact, although the elder did seem to easily guess after only one comment by Pecksniff that the grandson may be coveting his money. Many questions at this point.

I don't know if I've already mentioned it, but Martin Chuzzlewit is one of my favourite Dickens novels, partly because my favourite Dickens character (apart from Mr. Wegg) is making her appearance in its pages, but partly also because of the dark atmosphere that pervades most of the story. Unlike most of you, I most of all enjoy the grotesque and dark sides of Dickens, and there are plenty here. The family reunion was a feast for me, what with all those selfish people trying to outwit each other and pulling the rug from under each other's feet. And yes, Mr. Tigg is an invaluable character, especially when he professes that he is too modest to try to pass for Slyme. The name, Chevy Slyme, alone is worth a mine of gold, and the interactions of all those terrible people are highly entertaining.

It's also quite nice to read about good Tom going to Salisbury - especially because Dickens is good at creating atmospheres, and if there is somebody who can write an entertaining description of a happy day or a jolly encounter (things that are normally not too interesting in literature), it's certainly Dickens. Let's only hope that we will not have too many scenes of Mary Graham showing how self-denyingly good and trusting and gentle she is! For that is bound to be boring and we already had Nell, and Emma, and Little Red Ridinghood ...

Young Martin is a very interesting character, because he seems to be flawed in some ways. Julie pointed them out very clearly - by the way, Julie, it would be a pity if you skipped this novel: a pity for the group, but probably also a pity for you because there is lot to like about Martin Chuzzlewit. Being slightly flawed, but not altogether bad, young Martin will probably be the centre of the book, since he promises a lot of development.

Nevertheless, can we be sure that young Martin is the eponymous hero? It could also be old Martin, especially if we go by the long title provided by Kim where reference is made to Martin's wills. Haven't we just seen old Martin ponder on his will. So, is the novel named for old or for young Martin? It's probably the same conundrum as in the case of the film The Big Lebowski ...

It's also quite nice to read about good Tom going to Salisbury - especially because Dickens is good at creating atmospheres, and if there is somebody who can write an entertaining description of a happy day or a jolly encounter (things that are normally not too interesting in literature), it's certainly Dickens. Let's only hope that we will not have too many scenes of Mary Graham showing how self-denyingly good and trusting and gentle she is! For that is bound to be boring and we already had Nell, and Emma, and Little Red Ridinghood ...

Young Martin is a very interesting character, because he seems to be flawed in some ways. Julie pointed them out very clearly - by the way, Julie, it would be a pity if you skipped this novel: a pity for the group, but probably also a pity for you because there is lot to like about Martin Chuzzlewit. Being slightly flawed, but not altogether bad, young Martin will probably be the centre of the book, since he promises a lot of development.

Nevertheless, can we be sure that young Martin is the eponymous hero? It could also be old Martin, especially if we go by the long title provided by Kim where reference is made to Martin's wills. Haven't we just seen old Martin ponder on his will. So, is the novel named for old or for young Martin? It's probably the same conundrum as in the case of the film The Big Lebowski ...

Tristram wrote: "I don't know if I've already mentioned it, but Martin Chuzzlewit is one of my favourite Dickens novels, partly because my favourite Dickens character (apart from Mr. Wegg) is making her appearance ..."

Tristram wrote: "I don't know if I've already mentioned it, but Martin Chuzzlewit is one of my favourite Dickens novels, partly because my favourite Dickens character (apart from Mr. Wegg) is making her appearance ..."I agree with you, Tristram! I found the latter part of chapter four hilarious, and in many ways, is one of the reasons why I like Dickens so much. I read aloud to several friends the small part where Charity Pecksniff is fighting with the Spottletoe sisters:

“Miss Charity Pecksniff begged with much politeness to be informed whether any of those very low observations were leveled at her; and receiving no more explanatory answer than was conveyed in the adage ‘those the cap fits, let them wear it,’ immediately commenced a somewhat acrimonious and personal retort.” I think why this struck me as so funny is because of how modern this sounds? I’m sure we’ve all heard of the expression “if the shoe fits!”

Also, this family gathering reminded me of the fact that we are almost in the midst of holiday season wherein many people are going to be spending time with family members they might not get along with (to say the least!). Maybe I have a dark sense of humor, but I thought this whole scene was comedic perfection.

Also, now I'm really intrigued by your final question! I assumed the title referred to younger Martin, but maybe it does refer to Martin Sr.? How fascinating! Or, perhaps the ambiguity is significant or purposefully telling? I'll be thinking about this as we continue reading!

Evening all-a late joiner after missing last weeks first discussion.

Evening all-a late joiner after missing last weeks first discussion.Having just read Chapter 4, I wholeheartedly agree with the comments above in relation to how enjoyable the family meeting is-a great callback to chapter ones overview of the Chuzzlewit family traits, and you can already imagine the types of schemes they’re all plotting. Quite telling that not one of them expresses any real concern for their struggling relative, even if to simply try and claim the moral high ground in the room (other than Pecksniff using a few terms with double meanings-“our very dear...relative” and “our valued relative”). A family where the moral high ground holds no (or even negative) worth?

The only other thing I’d add was how much I enjoyed the introductory description of Montague Tigg-I thought this was Dickens at his character building best; you could practically smell Tigg, such a vivid depiction!

Chris wrote: "Evening all-a late joiner after missing last weeks first discussion.

Chris wrote: "Evening all-a late joiner after missing last weeks first discussion.Having just read Chapter 4, I wholeheartedly agree with the comments above in relation to how enjoyable the family meeting is-a..."

Oh, yes, I could smell him too.

Emma wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don't know if I've already mentioned it, but Martin Chuzzlewit is one of my favourite Dickens novels, partly because my favourite Dickens character (apart from Mr. Wegg) is makin..."

Emma,

It's nice to know that I am not alone in my warped admiration for the Chuzzlewit family reunion ;-) Interestingly, in German we also say something like "If the shoe fits you, put it on", but we also have "If it itches you, you'll scratch yourself."

Emma,

It's nice to know that I am not alone in my warped admiration for the Chuzzlewit family reunion ;-) Interestingly, in German we also say something like "If the shoe fits you, put it on", but we also have "If it itches you, you'll scratch yourself."

Chris wrote: "(other than Pecksniff using a few terms with double meanings-“our very dear...relative” and “our valued relative”)"

Chris,

It's a very nice observation; I didn't notice that Pecksniff's seemingly respectful references to his "dear" relative are highly equivocal. I am sure the happy family can hardly under-estimate old Martin Chuzzlewit ;-)

Chris,

It's a very nice observation; I didn't notice that Pecksniff's seemingly respectful references to his "dear" relative are highly equivocal. I am sure the happy family can hardly under-estimate old Martin Chuzzlewit ;-)

Peter wrote: "Mark Tapley is a curiously cheerful person who seems to almost go in search of problems or sadness in life."

Peter wrote: "Mark Tapley is a curiously cheerful person who seems to almost go in search of problems or sadness in life."Is he though?

Mark seems to me to be a bit of a self-flagellater. He is not satisfied being jolly; he needs to test his jolliness, make sure it can stand up to misery.

He thinks marrying might be jolly, but how much jollier it would be if his children had the measles. This is no small matter back then. Measles was a scourge; many children died. Is it appropriate to want to be jolly when your children have the measles in Victorian England?

I think not.

I love Dickens' descriptions of the stores. What an interesting time it must have been. Capital and investment has produced wealth, and we see some of the results of it here. How awesome it must have been, for the first time in your life, to walk along a street of shops and look at all the wonderful wares for sale. Things that could make life a little easier and more enjoyable. Tom Pinch certainly thinks so.

I love Dickens' descriptions of the stores. What an interesting time it must have been. Capital and investment has produced wealth, and we see some of the results of it here. How awesome it must have been, for the first time in your life, to walk along a street of shops and look at all the wonderful wares for sale. Things that could make life a little easier and more enjoyable. Tom Pinch certainly thinks so. I know. I know. How unwoke of me to speak of capital and investment in such a way. Well, when we get to High Times, perhaps I'll have another view of it.

Exactly how much can a horse pull? One horse pulling a carriage, two people, and a box which must have some weight behind it; it's certainly big enough. Right Tom???

Exactly how much can a horse pull? One horse pulling a carriage, two people, and a box which must have some weight behind it; it's certainly big enough. Right Tom???I still have this image in my mind of Charity knitting impractical head caps for the poor. It won't go away. No one but Dickens would say it so succinctly and wonderfully.

Is it only me who thinks Pecksniff is being disingenuous when he claims to be surprised at how quickly Tom and Martin have arrived? Too quick for him to have thrown the reception he said he had intended.

EDIT: Perhaps I should finish the chapter before commenting :) Looks like they did plan a reception, although based on Tom's comment to himself, this is very much out of the ordinary and probably done for the reason Peter suggests.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Peter wrote: "Mark Tapley is a curiously cheerful person who seems to almost go in search of problems or sadness in life."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Peter wrote: "Mark Tapley is a curiously cheerful person who seems to almost go in search of problems or sadness in life."Is he though?

Mark seems to me to be a bit of a self-flagellater. He is ..."

I agree with you. This is how I read Mark Tapley as well. I honestly found this character very confusing, and I hope he becomes a bit more clear as MC continues. I had to reread this small interaction between Mark Tapley and Tom Pinch several times. It's so odd, and I struggle to make sense of it. Mark is continuously happy (in a way that almost seems like he can't control himself?), but feels that true happiness can only arise by putting oneself in complete misery/miserable circumstances. Thus, if you can be happy in that setting, then you know you are truly happy? Is he afraid of being"too" happy without reason? That almost seems Puritanical. Perhaps, in a theoretical way, this makes sense, but in terms of developing a character, it's really baffling. To me, Mark Tapley seems more like a character or stereotype from a medieval morality play than someone you would encounter in real life, no?

Yes, Emma, and note he is wearing just a shirt and it's very cold outside. And he's walking. Your response has me thinking abour him more.

Yes, Emma, and note he is wearing just a shirt and it's very cold outside. And he's walking. Your response has me thinking abour him more.He can't control himself. So far, I don't see him as funny as I do sad. He has a way of talking that makes us think of him as optimistic. But this really isn't optimism.

But this is Dickens, so he could end up being hilarious. We will see.

Emma wrote: "To me, Mark Tapley seems more like a character or stereotype from a medieval morality play than someone you would encounter in real life, no?"

Emma wrote: "To me, Mark Tapley seems more like a character or stereotype from a medieval morality play than someone you would encounter in real life, no?"That might be why I like him! :)

Another plus is that now the widow is a jilted widow, which will bring her enough hardship that we might get to see more of her, contrary to my earlier guess that she was too pleasant and happy to stay in the narrative long. So that's good.

Tristram wrote: "by the way, Julie, it would be a pity if you skipped this novel: a pity for the group, but probably also a pity for you because there is lot to like about Martin Chuzzlewit. Being slightly flawed, but not altogether bad, young Martin will probably be the centre of the book, since he promises a lot of development."

Tristram wrote: "by the way, Julie, it would be a pity if you skipped this novel: a pity for the group, but probably also a pity for you because there is lot to like about Martin Chuzzlewit. Being slightly flawed, but not altogether bad, young Martin will probably be the centre of the book, since he promises a lot of development."Well, thank you! and I do like young slightly selfish but pleasant and promising Martin, so I'll stick it out for at least another number. Also I kind of want to see the famous travel portion of the book.

Tristram wrote: "Let's only hope that we will not have too many scenes of Mary Graham showing how self-denyingly good and trusting and gentle she is! For that is bound to be boring and we already had Nell, and Emma, and Little Red Ridinghood ..."

Do you ever manage to like the person we are supposed to like?

Do you ever manage to like the person we are supposed to like?

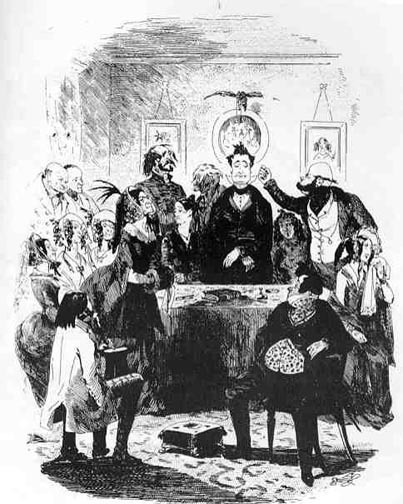

Pleasant Little Family Party at Mr. Pecksniff's

Chapter 4

Phiz

February 1843

Text Illustrated: The Gallery of Chuzzlewits Particularized:

But when the company arrived! That was the time. When Mr Pecksniff, rising from his seat at the table's head, with a daughter on either hand, received his guests in the best parlour and motioned them to chairs, with eyes so overflowing and countenance so damp with gracious perspiration, that he may be said to have been in a kind of moist meekness! And the company; the jealous stony-hearted distrustful company, who were all shut up in themselves, and had no faith in anybody, and wouldn’t believe anything, and would no more allow themselves to be softened or lulled asleep by the Pecksniffs than if they had been so many hedgehogs or porcupines!

First, there was Mr. Spottletoe who was so bald and had such big whiskers, that he seemed to have stopped his hair, by the sudden application of some powerful remedy, in the very act of falling off his head, and to have fastened it irrevocably on his face. Then there was Mrs. Spottletoe, who being much too slim for her years, and of a poetical constitution, was accustomed to inform her more intimate friends that the said whiskers were ‘the lodestar of her existence;’ and who could now, by reason of her strong affection for her uncle Chuzzlewit, and the shock it gave her to be suspected of testamentary designs upon him, do nothing but cry — except moan. Then there were Anthony Chuzzlewit, and his son Jonas; the face of the old man so sharpened by the wariness and cunning of his life, that it seemed to cut him a passage through the crowded room, as he edged away behind the remotest chairs; while the son had so well profited by the precept and example of the father, that he looked a year or two the older of the twain, as they stood winking their red eyes, side by side, and whispering to each other softly. Then there was the widow of a deceased brother of Mr. Martin Chuzzlewit, who being almost supernaturally disagreeable, and having a dreary face and a bony figure and a masculine voice, was, in right of these qualities, what is commonly called a strong-minded woman; and who, if she could, would have established her claim to the title, and have shown herself, mentally speaking, a perfect Samson, by shutting up her brother-in-law in a private madhouse, until he proved his complete sanity by loving her very much. Beside her sat her spinster daughters, three in number, and of gentlemanly deportment, who had so mortified themselves with tight stays, that their tempers were reduced to something less than their waists, and sharp lacing was expressed in their very noses. Then there was a young gentleman, grandnephew of Mr. Martin Chuzzlewit, very dark and very hairy, and apparently born for no particular purpose but to save looking-glasses the trouble of reflecting more than just the first idea and sketchy notion of a face, which had never been carried out. Then there was a solitary female cousin who was remarkable for nothing but being very deaf, and living by herself, and always having the toothache. Then there was George Chuzzlewit, a gay bachelor cousin, who claimed to be young but had been younger, and was inclined to corpulency, and rather overfed himself; to that extent, indeed, that his eyes were strained in their sockets, as if with constant surprise; and he had such an obvious disposition to pimples, that the bright spots on his cravat, the rich pattern on his waistcoat, and even his glittering trinkets, seemed to have broken out upon him, and not to have come into existence comfortably. Last of all there were present Mr Chevy Slyme and his friend Tigg. And it is worthy of remark, that although each person present disliked the other, mainly because he or she did belong to the family, they one and all concurred in hating Mr. Tigg because he didn’t.

Such was the pleasant little family circle now assembled in Mr Pecksniff’s best parlour, agreeably prepared to fall foul of Mr. Pecksniff or anybody else who might venture to say anything whatever upon any subject.

"This," said Mr. Pecksniff, rising and looking round upon them with folded hands, "does me good. It does my daughters good. We thank you for assembling here. We are grateful to you with our whole hearts. It is a blessed distinction that you have conferred upon us, and believe me" — it is impossible to conceive how he smiled here — "we shall not easily forget it."

"I am sorry to interrupt you, Pecksniff," remarked Mr. Spottletoe, with his whiskers in a very portentous state; "but you are assuming too much to yourself, sir. Who do you imagine has it in contemplation to confer a distinction upon you, sir?"

A general murmur echoed this inquiry, and applauded it.

Commentary: The Great Chuzzlewit Consult:

Thir dread commander: he above the rest

In shape and gesture proudly eminent

Stood like a Tow'r; his form had yet not lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear'd

Less than Arch-Angel ruin'd. . . . [Paradise Lost, I, 589-93]

In the first two monthly installments, Dickens establishes the novel’s governing motif of "self" through the pettiness of the Chuzzlewit clan, who have descended upon the little Wiltshire village in pursuit the wealthy old Martin. Phiz has already depicted the sanctimonious Wiltshire village architect Seth Pecksniff and his egocentric daughters in the first serial illustration, Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters, so that serial readers could recognise Pecksniff in this, his second appearance. For this initial illustration in the second monthly number Phiz provides both a reprise of the hypocritical Pecksniff and a group study of the extended Chuzzlewit family, with the familiar figure of Pecksniff in their midst, the calm eye in the midst of the storm. Pecksniff, who presents himself as pious throughout Martin Chuzzlewit anticipates the "umble" villain of David Copperfield (1849-50), Uriah Heep, who is, in essence, Pecksniff re-visited and re-vitalized. In this third serial illustration, the greedy Pecksniff attempts to seize the leadership of the hopeful legatees of Old Martin. Phiz mockingly underscores Pecksniff's assumption of leader and pious protector by making a picture frame behind him appear like an oval halo. Michael Steig has detected in this background picture a reproduction of Jacques-Louis David's The Coronation of Napoleon (1805-7), which depicts the Emperor of the French, who has recently seized power in a coup d'etat. This embedded picture serves two other purposes, namely to provide a halo for the hypocrite's head and to render him the focal point of the entire composition. Other pictures likewise halo the heads of Tigg the swindler (left) and the splenetic Spottletoe (right). These mock halos, which imply that Pecksniff is the center of an unholy trinity, thereby make this illustration a parody of Milton's "Great Consult" in the first book of Paradise Lost Satan addresses the other among the rebel angels. Phiz places Tigg's head in exact parallel to Pecksniff's, perhaps to imply that this parasite and swindler resembles Pecksniff in his posturing and deceipt.

Phiz's image of Seth Pecksniff as a great pretender accurately presents Dickens's conception of the novel's central antagonist. Apparently, Dickens based his characterization on philanthropist and writer S. C. Hall, who was born in 1800, and therefore would have about Pecksniff's age at the time that Dickens wrote Martin Chuzzlewit. As an inveterate snob and deceiver, Pecksniff effectively underscores Dickens's theme about the negative effects of egotism and hypocrisy. Phiz may also use the oval frame to make the village architect a parodic inversion of Christ at His baptism in which a black imperial eagle replaces the Holy Dove with a black "imperial" eagle hovering above the apostolic head. The eagle motif, which Steig discovered in three other Phiz series, may also suggest the more predatory motive underlying the family gathering. Around the upright pillar of Seth Pecksniff the vulture-like members of the extended Chuzzlewit clan swirl in consternation at his presumption in thinking of himself as their natural leader. Following Dickens's description of the scene, Phiz has included fourteen additional figures: the two flanking Miss Pecksniffs (the ironically named Charity and Mercy) reiterated by their pictures which hang conspicuously on the rear wall, right and left; the bald, splenetic cousin, Mr. Spottletoe (down left in this stage scene); the wary, cunning Anthony Chuzzlewit and his diabolical son, Jonas, up right; the widow of the senior Martin's brother and three spinster daughters, stage right of Pecksniff; Martin senior's grand-nephew, "very dark and very hairy"; the "gay bachelor cousin" and relict of the Regency, George Chuzzlewit, the corpulent figure, his waistcoat bulging, seated down left; Montague Tigg and his protégé, Chevy Slyme, being the figures immediately to Pecksniff's right. The composition as a whole, a scene of comic disorder, follows Dickens's principle of grouped pairs balanced to the left and right of the prop and pillar of the House of Chuzzlewit, in front of whom (appropriate to his self-appointed role as "Prince of Peace") is a closed Bible on the covered table. Dickens's verbal description, with such telling details as Pecksniff's crossed hands and the look-alike duo of Anthony and Jonas Chuzzlewit, has given Phiz plenty of material for visual elaboration. The moment realized, not hinted at in the generalized caption, is Spottletoe's denunciation of Pecksniff for presuming to be the head of the clan despite the fact that his name is not even "Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz have based the ironic caption on a phrase a few lines ahead of Spottletoe's denunciation, "the pleasant little family circle." As Steig points out, “Browne has carefully differentiated the characters, giving Tigg, the hanger-on, a prominent position and having Mercy and Charity react according to their personalities, the former amused and astonished, the latter vinegary and disdainful”.

Phiz's best dramatic invention is having Spottletoe's shake his fist in the seraphic face of Pecksniff; far more significant, however, are the emblematic embellishments already noted in for Pecksniff, particularly his beatific head, crowned by spiky hair and haloed by the circular coronation piece. If the composition has a weak point, other than its crowded effect, it is that Phiz depicts characters who are not so much individuals with particular motives as what Guerard has termed "thematic données", the scavengers who as in Ben Jonson's Volpone have gathered to rend asunder the carcass once the chief beast expires.

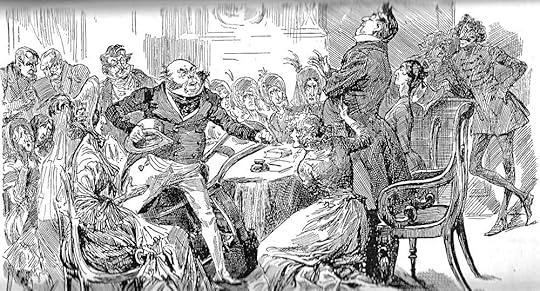

Mr. Spottletoe stands up to Mr. Pecksniff

Chapter 4

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

First, there was Mr. Spottletoe, who was so bald and had such big whiskers, that he seemed to have stopped his hair, by the sudden application of some powerful remedy, in the very act of falling off his head, and to have fastened it irrevocably on his face. Then there was Mrs Spottletoe, who being much too slim for her years, and of a poetical constitution, was accustomed to inform her more intimate friends that the said whiskers were "the lodestar of her existence;" and who could now, by reason of her strong affection for her uncle Chuzzlewit, and the shock it gave her to be suspected of testamentary designs upon him, do nothing but cry — except moan. — Chapter Four, "From Which It Will Appear That If Union Be Strength, and Family Affection Be Pleasant To Contemplate, the Chuzzlewits Were the Strongest and Most Agreeable Family in the World," p. 57

Such was the pleasant little family circle now assembled in Mr. Pecksniff's best parlour, agreeably prepared to fall foul of Mr. Pecksniff or anybody else who might venture to say anything whatever upon any subject.

"This," said Mr. Pecksniff, rising and looking round upon them with folded hands, "does me good. It does my daughters good. We thank you for assembling here. We are grateful to you with our whole hearts. It is a blessed distinction that you have conferred upon us, and believe me" — it is impossible to conceive how he smiled here — "we shall not easily forget it."

"I am sorry to interrupt you, Pecksniff," remarked Mr. Spottletoe, with his whiskers in a very portentous state; "but you are assuming too much to yourself, sir. Who do you imagine has it in contemplation to confer a distinction upon you, Sir?

A general murmur echoed this inquiry, and applauded it.

"If you are about to pursue the course with which you have begun, Sir," pursued Mr. Spottletoe in a great heat, and giving a violent rap on the table with his knuckles, "the sooner you desist, and this assembly separates, the better. I am no stranger, Sir, to your preposterous desire to be regarded as the head of this family, but I can tell you, Sir —?"

Oh yes, indeed! He tell. He! What? He was the head, was he? From the strong-minded woman downwards everybody fell, that instant, upon Mr. Spottletoe, who after vainly attempting to be heard in silence was fain to sit down again, folding his arms and shaking his head most wrathfully, and giving Mrs Spottletoe to understand in dumb show, that that scoundrel Pecksniff might go on for the present, but he would cut in presently, and annihilate him. — Chapter Four, "From Which It Will Appear That If Union Be Strength, and Family Affection Be Pleasant To Contemplate, the Chuzzlewits Were the Strongest and Most Agreeable Family in the World.

Commentary:

In Mr. Spottletoe stands up to Mr. Pecksniff, the passage that Furniss had in mind was highly specific:

"If you are about to pursue the course with which you have begun, Sir," pursued Mr. Spottletoe in a great heat, and giving a violent rap on the table with his knuckles, "the sooner you desist, and this assembly separates, the better." — Martin Chuzzlewit, p. 58.

Any discussion of the novel's character comedy must include the work of Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, who from his visualizations for The Pickwick Papers onward remained the writer's initial interpreter and gifted co-presenter. Later illustrators, including Fred Barnard in the Household Edition continued to employ the pictorial conventions established by the original illustrations, but re-interpreted them in a more realistic manner, often, however, stripping his illustrations of the embedded symbols and texts that constitute Phiz's editorial commentary upon his material. Harry Furniss, the great impressionist, with his encyclopedic knowledge of Dickens and the visual traditions provided by Phiz, George Cruikshank and the other original illustrator was particularly well-suited to offer updated reinterpretations of many of the most famous scenes from Dickens, including the Phiz illustration for the fourth chapter, Pleasant Little Family Party at Mr. Pecksniff's (February 1843).

Phiz's steel engraving, a brilliant study of Pecksniff's facing down a parlour full of avaricious Chuzzlewit relatives, was not easily equalled, but, using the realistic medium and larger scale of the composite wood-engraving, Harry Furniss utilized the visual conventions of the original Phiz illustrations (Spottletoe as the Angry Man of Victorian comedy and Pecksniff's lantern-jawed face and peculiar hairstyle) which continued into the Household Edition illustrations of Fred Barnard. However, gives the reader a sharper sense of the other relatives who have descended upon the Wiltshire village in pursuit of Old Martin Chuzzlewit's fortune. Phiz's best piece of dramatic invention is capturing Spottletoe's shaking his fist in the angelic face of Pecksniff; far more significant, however, are the emblematic embellishments already noted in for Pecksniff, particularly head, crowned by spiky hair and haloed by the circular coronation piece. If the illustration has a weak point, other than its crowded effect, it is that it depicts characters who are not so much individuals pursuing particular motives as what Guerard has termed "thematic données", the scavengers who as in Ben Jonson's Volpone have gathered to rend asunder the carcass once the chief beast expires.

As opposed to the Phiz tableau featuring Pecksniff as the calm centre of the eye of the domestic storm, Furniss has infused the scene with the vigor of a stage scene in progress, with Spottletoe caught in the midst striding forward to strike Pecksniff as his younger daughter tries to gain his attention about the impending assault. Through providing many of the relatives with similar facial features Furniss suggests their common motivation, and the feathers in the ladies' hats imply a vulture-like attention to the main chance. The figures that stand out as individuals are Spottletoe (left of center), Pecksniff (right of center) and Montague Tigg (right rear). A clever piece of visual commentary on the text is Pecksniff's throne-like dining-chair.

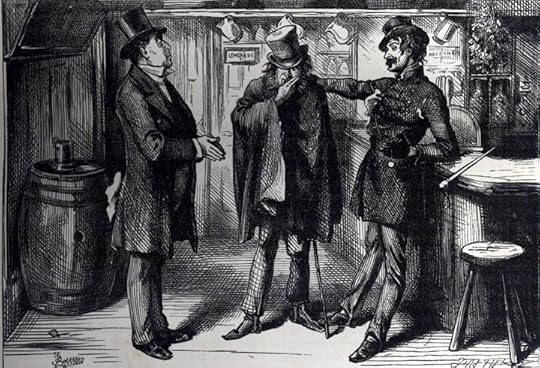

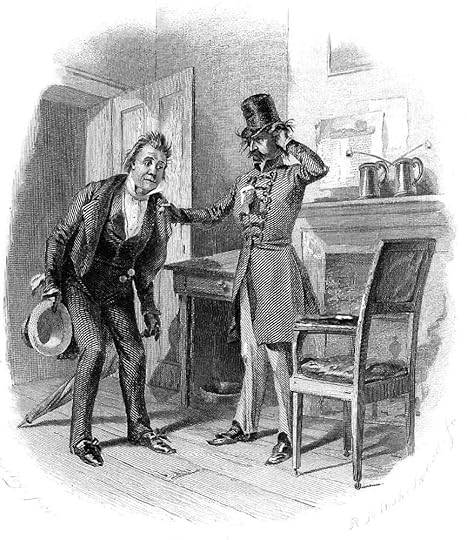

Mr. Pecksniff is introduced to a relative by Mr. Tigg

Chapter 4

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

It happened on the fourth evening, that Mr. Pecksniff walking, as usual, into the bar of the Dragon and finding no Mrs. Lupin there, went straight up-stairs; purposing, in the fervour of his affectionate zeal, to apply his ear once more to the keyhole, and quiet his mind by assuring himself that the hard-hearted patient was going on well. It happened that Mr. Pecksniff, coming softly upon the dark passage into which a spiral ray of light usually darted through the same keyhole, was astonished to find no such ray visible; and it happened that Mr. Pecksniff, when he had felt his way to the chamber-door, stooping hurriedly down to ascertain by personal inspection whether the jealousy of the old man had caused this key-hole to be stopped on the inside, brought his head into such violent contact with another head that he could not help uttering in an audible voice the monosyllable "Oh!" which was, as it were, sharply unscrewed and jerked out of him by very anguish. It happened then, and lastly, that Mr. Pecksniff found himself immediately collared by something which smelt like several damp umbrellas, a barrel of beer, a cask of warm brandy-and-water, and a small parlor-full of stale tobacco smoke, mixed; and was straightway led down-stairs into the bar from which he had lately come, where he found himself standing opposite to, and in the grasp of, a perfectly strange gentleman of still stranger appearance who, with his disengaged hand, rubbed his own head very hard, and looked at him, Pecksniff, with an evil countenance.

The gentleman was of that order of appearance which is currently termed shabby-genteel, though in respect of his dress he can hardly be said to have been in any extremities, as his fingers were a long way out of his gloves, and the soles of his feet were at an inconvenient distance from the upper leather of his boots. His nether garments were of a bluish gray — violent in its colors once, but sobered now by age and dinginess — and were so stretched and strained in a tough conflict between his braces and his straps, that they appeared every moment in danger of flying asunder at the knees. His coat, in color blue and of a military cut, was buttoned and frogged up to his chin. His cravat was, in hue and pattern, like one of those mantles which hairdressers are accustomed to wrap about their clients, during the progress of the professional mysteries. His hat had arrived at such a pass that it would have been hard to determine whether it was originally white or black. But he wore a mustache — a shaggy moustache too: nothing in the meek and merciful way, but quite in the fierce and scornful style: the regular Satanic sort of thing — and he wore, besides, a vast quantity of unbrushed hair. He was very dirty and very jaunty; very bold and very mean; very swaggering and very slinking; very much like a man who might have been something better, and unspeakably like a man who deserved to be something worse. — Chapter Four

Commentary:

Here, Mr. Pecksniff and the reader meet the sullen and impecunious Chuzzlewit nephew Chevy Slyme and his suave but down-at-heel hanger-on, Montague Tigg.

In selecting his subjects for the second volume of the Household Edition Fred Barnard flags as significant the meeting of the novel's two greatest posers, the hypocritical provincial architect, Seth Pecksniff, and the Chuzzlewit hanger-on and disgraced military officer, Montague Tigg. This illustration, like others featuring these two, is useful in underscoring one of the novel's principal themes: the ridiculing of fraud, duplicity, and egocentricity. Focusing on the book's arch-hypocrite in chapter four, Phiz's third illustration (for the second monthly installment), Pleasant little family party at Mr. Pecksniff's depicts the admirable Pecksniff as pre-eminent among the exploitative, egocentric Chuzzlewit clan that has just descended upon the little Wiltshire village in pursuit of the patriarchal Martin, Senior's favor. In the next decade, in the Household Edition volume of 1872 Barnard introduces two of novel's objects of satire in Mr. Pecksniff is introduced to a relative by Mr. Tigg. Pecksniff appears yet again in the first movement of story, here in his initial meeting with the scapegrace but beguiling Tigg (who, of course, is not a Chuzzlewit) who has attached himself to a particularly imbecilic specimen. Barnard's theatrical scene possesses anatomical accuracy and fluid posing of the figures in an appropriate setting (a taproom), but lacks the physical humor evident in Darley's initial frontispiece of 1862.

Although The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit was a nineteen-month serialization, and remains a sprawling narrative that encompasses a great range of characters, most of them humorous distortions and caricatures, and spans two continents and two societies, one has little sense of the original's group scenes, although Barnard does capture something of Phiz's comic richness and diversity in his treatment of the hypocritical architect and the swindling financier, even though he does little with the composition's central figure, "Chevy Slyme, Esquire."

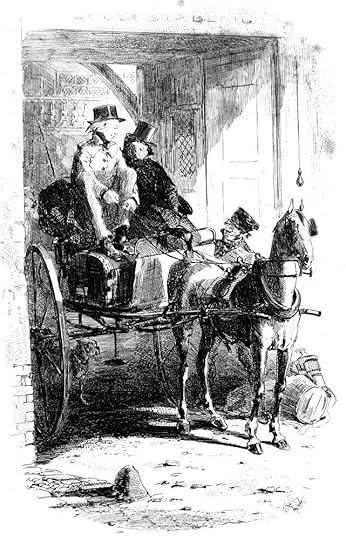

Pinch Starts Homeward with The New Pupil

Chapter 5

Phiz

February 1843

Text Illustrated: Mr. Pinch picks up the New Pupil

It was not precisely of that convenient size which would admit of its being squeezed into any odd corner, but Dick the hostler got it in somehow, and Mr. Chuzzlewit helped him. It was all on Mr Pinch's side, and Mr. Chuzzlewit said he was very much afraid it would encumber him; to which Tom said, "Not at all;" though it forced him into such an awkward position, that he had much ado to see anything but his own knees. But it is an ill wind that blows nobody any good; and the wisdom of the saying was verified in this instance; for the cold air came from Mr Pinch's side of the carriage, and by interposing a perfect wall of box and man between it and the new pupil, he shielded that young gentleman effectually; which was a great comfort. [Chapter 5]

Commentary:

This illustration for the February 1843 number, which introduces more significant characters, contrasts the pleasant shared experience of setting out from the inn on the plodding ride home from Salisbury with the acrimoniousness of the family meeting depicted in the previous plate, Pleasant little family party at Mr. Pecksniff (plate). The genuine friendliness of the kindly Tom Pinch towards the new architectural apprentice sharply contrasts the dark assemblage of the House of Chuzzlewit over which presides the bad eminence of Pecksniff, a black pillar of calm and complacency amidst the fractiousness of the greedy relatives of Old Martin. Instead of multiple figures in a variety of poses in the Pecksniff dining-room, the reader encounters two young men on the gig as the hostler prepares to hoist the brooding newcomer's luggage into the back of the vehicle. Tom, who cheerfully accommodates Martin's having placed his large steamer-trunk behind the footboard, genially addresses the inn's bluff-looking functionary. Young Martin, however, has muffled himself up inside his great-coat, signifying his aloofness and oyster-like emotional state. The gallery of the old coaching inn appears through the archway. Readers of The Pickwick Papers had encountered such an old-fashioned inn, which was fast becoming an anachronism in the railway age. Steig notes that the juxtaposition between this and the other plate for the second monthly installment contrasts brooding Martin and the man who in time he might have become if his egotism had received no check, his "degraded relative" Chevy Slyme:

It is one of the ironies of young Martin's lack of self-awareness that he in so many ways resembles those he disdains. This irony is brought out in "Pinch starts homeward with the new Pupil" (ch. 5) through the similarity of Martin's head, halfway submerged in its collar, and that of his degraded relative Chevy Slyme — the man he later so urgently wishes to avoid — in the preceding plate. Slyme in his abjectness is the embodiment of total selfishness and is admired as such by the sycophantic Tigg. Thus this plate marks a significant beginning of Martin's progress. [Steig, Chapter 3, p. 66]

He turned a whimsical face and a very merry pair of blue eyes on Mr. Pinch.

Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Commentary:

Thirty years earlier in the original serial publication, in Phiz's fifth monthly illustration, "Pinch starts homeward with the new pupil," twenty-five-year-old Mark Tapley, the hostler at the Blue Dragon in the little Wiltshire village that serves as the novel's initial setting, is largely hidden from the reader's view by Pecksniff's broken-down nag; Phiz has even obscured Mark's perpetually merry physiognomy under a non-textual fur hat, with the result that reader-viewers in the original monthly installment did not properly see the illustrated Mark begin his progress until the sixth illustration (March 1843).

Having read the entire text in advance and therefore having realized the importance of the jovial Mark to the subsequent narrative, Fred Barnard divides the focus of the composition between a full-length study of Mark Tapley, blocking our view of Pecksniff's horse (not nearly the nag of Dickens's description or Phiz's plate), and a representation of a substantial gig, surmounted by another significant though secondary character, Tom Pinch, not previously introduced in Barnard's sequence.

Whereas Phiz has realized a moment later in Chapter 5 in order to introduce young Martin, Barnard has chosen to depict the initial appearance of the Dickensian Sancho Panza in a rustic setting. Prominent here are Mark's neck-cloth, its long ends giving his figure a dashing quality, and the winter berries and greenery in his buttonhole, imbuing him with the life-force of a woodland deity or the spirit of Christmas Present in A Christmas Carol (1843). The slouchy-brimmed hat and riding pants (not specified by the authorial voice) contribute to an overall impression of the whimsical character's jauntiness.

The mutual destination of Tom and Mark, Salisbury, Barnard indicates by the cathedral spire (center) rising in the distance between the two. Twice Dickens employs the adjective "spruce" to characterize Mark, whose social status and character are signified in the illustration by the contrast in his attire and Tom's. The architectural apprentice's posture implies both curiosity and deference, whereas Mark's easy swagger betokens a thorough self-confidence. Barnard has substituted the soft had with dented crown and uneven brim for Phiz's beaver (from the March 1843 plate "Mark begins to be jolly under creditable circumstances") as an assertion of his working-class origins. Except for the breeches with top-pockets, conveying a certain horsiness suitable to the hostler of the Blue Dragon, the remainder of Mark's attire is consistent with Phiz's illustrations and Dickens's descriptions. Despite his Kentish origin and London background, Barnard's Mark looks a thorough countryman.

"Let us be merry.' Here he took a captain's biscuit".

Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Here a great change had taken place; for festive preparations on a rather extensive scale were already completed, and the two Miss Pecksniffs were awaiting their return with hospitable looks. There were two bottles of currant wine, white and red; a dish of sandwiches (very long and very slim); another of apples; another of captain’s biscuits (which are always a moist and jovial sort of viand); a plate of oranges cut up small and gritty; with powdered sugar, and a highly geological home-made cake. The magnitude of these preparations quite took away Tom Pinch’s breath; for though the new pupils were usually let down softly, as one may say, particularly in the wine department, which had so many stages of declension, that sometimes a young gentleman was a whole fortnight in getting to the pump; still this was a banquet; a sort of Lord Mayor’s feast in private life; a something to think of, and hold on by, afterwards.

To this entertainment, which apart from its own intrinsic merits, had the additional choice quality, that it was in strict keeping with the night, being both light and cool, Mr Pecksniff besought the company to do full justice.

‘Martin,’ he said, ‘will seat himself between you two, my dears, and Mr Pinch will come by me. Let us drink to our new inmate, and may we be happy together! Martin, my dear friend, my love to you! Mr Pinch, if you spare the bottle we shall quarrel.’

And trying (in his regard for the feelings of the rest) to look as if the wine were not acid and didn’t make him wink, Mr Pecksniff did honor to his own toast.

‘This,’ he said, in allusion to the party, not the wine, ‘is a mingling that repays one for much disappointment and vexation. Let us be merry.’ Here he took a captain’s biscuit. ‘It is a poor heart that never rejoices; and our hearts are not poor. No!’

With such stimulants to merriment did he beguile the time, and do the honors of the table; while Mr Pinch, perhaps to assure himself that what he saw and heard was holiday reality, and not a charming dream, ate of everything, and in particular disposed of the slim sandwiches to a surprising extent. Nor was he stinted in his draughts of wine; but on the contrary, remembering Mr Pecksniff’s speech, attacked the bottle with such vigour, that every time he filled his glass anew, Miss Charity, despite her amiable resolves, could not repress a fixed and stony glare, as if her eyes had rested on a ghost. Mr Pecksniff also became thoughtful at those moments, not to say dejected; but as he knew the vintage, it is very likely he may have been speculating on the probable condition of Mr Pinch upon the morrow, and discussing within himself the best remedies for colic.

Martin and the young ladies were excellent friends already, and compared recollections of their childish days, to their mutual liveliness and entertainment. Miss Mercy laughed immensely at everything that was said; and sometimes, after glancing at the happy face of Mr Pinch, was seized with such fits of mirth as brought her to the very confines of hysterics. But for these bursts of gaiety, her sister, in her better sense, reproved her; observing, in an angry whisper, that it was far from being a theme for jest; and that she had no patience with the creature; though it generally ended in her laughing too—but much more moderately—and saying that indeed it was a little too ridiculous and intolerable to be serious about.

At length it became high time to remember the first clause of that great discovery made by the ancient philosopher, for securing health, riches, and wisdom; the infallibility of which has been for generations verified by the enormous fortunes constantly amassed by chimney-sweepers and other persons who get up early and go to bed betimes. The young ladies accordingly rose, and having taken leave of Mr Chuzzlewit with much sweetness, and of their father with much duty and of Mr Pinch with much condescension, retired to their bower. Mr Pecksniff insisted on accompanying his young friend upstairs for personal superintendence of his comforts; and taking him by the arm, conducted him once more to his bedroom, followed by Mr Pinch, who bore the light.

And was straightway let down stairs

Chapter 5

Felix O. C. Darley

1862

Text Illustrated: