The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC Chapters 24-26

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 25

Our chapter opens with Mr Mould enjoying his home on a warm day. Dickens takes the reader through his home and we learn more about his family and domestic arrangements. It is evident that his undertaking business is going well and a drink or two of punch helps in the family’s relaxation. Mrs Gamp comes to his home and brings with her the aroma of a wine-vault. Mrs Gamp tells Mrs Mould of a recent conversation she had with Mrs Harris. The tale tends to ramble on, but in general appears to be about friends and friendship. Soon after this Dickens informs his readers that the name of Harris “was a phantom of Mrs Gamp’s brain ... - created for the express purpose of holding visionary dialogues with her on all manner of subjects, and invariably winding up with a compliment to the excellence of her nature.” In general, it seems that the conversation is about change and the fact that “[t]here’s something besides births and berryins in the newspapers, an’t there?” What is besides these two events, according to Gamp, is “marryings.”

We learn that Mrs Gamp continues to take care of Chuffey during the day and has a good opinion of Jonas. How much of her good opinion of Jonas is because of the liquor available is not stated. We also learn that she has the opportunity to be a night nurse for another person who is ill. Mould sees no problem in Mrs Gamp doing both jobs but advises her not to tell Chuzzlewit she is earning an honest penny by moonlighting. The fact that Mrs Gamp has given Mould a lead to another possible corpse in the near future delights Mould. In fact, Mould is so pleased with Gamp’s lead on another possible corpse he comments “one would almost feel disposed to bury [Gamp] for nothing: and do it neatly, too.”

Going to the tavern for her night job Mrs Gamp overhears a conversation about the man she is to sit with. Evidently he is very ill, and John Westlock knows him slightly. Westlock agrees to pay for this mystery man’s medical bills and attentions.

Thoughts

Do you think Dickens had any intention beyond humour in revealing that Mrs Harris is merely a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination? If so, what might that intention be?

We are reminded that Mrs Gamp is also attending to Chuffey. How might Mrs Gamp’s presence in Jonas Chuzzlewit’s home help with the advancement of the plot?

Once again, John Westlock is introduced into the plot. What might be the purpose of him reappearing again? Who might be the seriously ill person be that Westlock has offered to care for at the tavern?

What do you think the purpose was of the conversation between Mr Mould and Mrs Gamp at the beginning of the chapter?

Mrs Gamp enters the Inn and goes to the chambers of her new client. There, she meets a Mrs Prig “who was of the Gamp build, but not so fat; and her voice was much deeper and more like a man’s. She also had a beard.” Well, that last sentence snapped my head back. Dickens just slips it in. If the name is not delightful enough the fact that she has a beard does add to her character profile. When Gamp asks Prig if there is anything she should know before Prig leaves she is informed that “the pickled salmon” is good as are the drinks. To that bit of information Mrs Gamp “expresses herself much gratified.” We learn that the patient is a “young man dark and not ill-looking- with long black hair.” His eyes were partially open and he did not utter any words although his head rolled from side to side. At one point Mrs Gamp pins his arms to his sides to see what he would look like as a corpse and is quite satisfied that “he’d make a lovely corpse.” Mrs Gamp orders a rather tasty sounding supper from the assistant chambermaid and settles into a meditative state where she muses that it is a blessed thing “to make sick people happy.” With that she settles into a sleep. Her sleep is disturbed by the patient beginning to cry out “Don’t drink so much ... .You’ll ruin us all. Don’t you see how the fountain sinks? Look at where the sparkling water was just now.!” He then began to count “One-two-three-four-five-six.” He then claims to see 521 men all dressed the same and follows that up with asking to be touched. Then Mrs Gamp hears a cry of “Chuzzlewit! Jonas! No!”

In the morning the doctor comes, Mr Westlake comes, as does Mrs Prig to be with the patient. To each person Mrs Gamp withholds the name of Jonas Chuzzlewit when asked if the patient made any sense in his rambling calling outs.

And so our chapter ends with more questions added but no answers discovered.

Thoughts

The obvious questions I have is who is this sickly man? What is his connection to Jonas Chuzzlewit? What’s with all the numbers?

We know that Mrs Gamp is also tending to Chuffey who was the servant to Anthony and is now tending the home for Jonas Chuzzlewit. There is a connection being drawn by Dickens. What might it be?

There is much delightful humour with Mrs Gamp in this chapter. Why might Dickens have employed humour in this chapter? How effectively has Dickens counterbalanced the seriousness of a very ill man with the character and actions of Mrs Gamp?

Our chapter opens with Mr Mould enjoying his home on a warm day. Dickens takes the reader through his home and we learn more about his family and domestic arrangements. It is evident that his undertaking business is going well and a drink or two of punch helps in the family’s relaxation. Mrs Gamp comes to his home and brings with her the aroma of a wine-vault. Mrs Gamp tells Mrs Mould of a recent conversation she had with Mrs Harris. The tale tends to ramble on, but in general appears to be about friends and friendship. Soon after this Dickens informs his readers that the name of Harris “was a phantom of Mrs Gamp’s brain ... - created for the express purpose of holding visionary dialogues with her on all manner of subjects, and invariably winding up with a compliment to the excellence of her nature.” In general, it seems that the conversation is about change and the fact that “[t]here’s something besides births and berryins in the newspapers, an’t there?” What is besides these two events, according to Gamp, is “marryings.”

We learn that Mrs Gamp continues to take care of Chuffey during the day and has a good opinion of Jonas. How much of her good opinion of Jonas is because of the liquor available is not stated. We also learn that she has the opportunity to be a night nurse for another person who is ill. Mould sees no problem in Mrs Gamp doing both jobs but advises her not to tell Chuzzlewit she is earning an honest penny by moonlighting. The fact that Mrs Gamp has given Mould a lead to another possible corpse in the near future delights Mould. In fact, Mould is so pleased with Gamp’s lead on another possible corpse he comments “one would almost feel disposed to bury [Gamp] for nothing: and do it neatly, too.”

Going to the tavern for her night job Mrs Gamp overhears a conversation about the man she is to sit with. Evidently he is very ill, and John Westlock knows him slightly. Westlock agrees to pay for this mystery man’s medical bills and attentions.

Thoughts

Do you think Dickens had any intention beyond humour in revealing that Mrs Harris is merely a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination? If so, what might that intention be?

We are reminded that Mrs Gamp is also attending to Chuffey. How might Mrs Gamp’s presence in Jonas Chuzzlewit’s home help with the advancement of the plot?

Once again, John Westlock is introduced into the plot. What might be the purpose of him reappearing again? Who might be the seriously ill person be that Westlock has offered to care for at the tavern?

What do you think the purpose was of the conversation between Mr Mould and Mrs Gamp at the beginning of the chapter?

Mrs Gamp enters the Inn and goes to the chambers of her new client. There, she meets a Mrs Prig “who was of the Gamp build, but not so fat; and her voice was much deeper and more like a man’s. She also had a beard.” Well, that last sentence snapped my head back. Dickens just slips it in. If the name is not delightful enough the fact that she has a beard does add to her character profile. When Gamp asks Prig if there is anything she should know before Prig leaves she is informed that “the pickled salmon” is good as are the drinks. To that bit of information Mrs Gamp “expresses herself much gratified.” We learn that the patient is a “young man dark and not ill-looking- with long black hair.” His eyes were partially open and he did not utter any words although his head rolled from side to side. At one point Mrs Gamp pins his arms to his sides to see what he would look like as a corpse and is quite satisfied that “he’d make a lovely corpse.” Mrs Gamp orders a rather tasty sounding supper from the assistant chambermaid and settles into a meditative state where she muses that it is a blessed thing “to make sick people happy.” With that she settles into a sleep. Her sleep is disturbed by the patient beginning to cry out “Don’t drink so much ... .You’ll ruin us all. Don’t you see how the fountain sinks? Look at where the sparkling water was just now.!” He then began to count “One-two-three-four-five-six.” He then claims to see 521 men all dressed the same and follows that up with asking to be touched. Then Mrs Gamp hears a cry of “Chuzzlewit! Jonas! No!”

In the morning the doctor comes, Mr Westlake comes, as does Mrs Prig to be with the patient. To each person Mrs Gamp withholds the name of Jonas Chuzzlewit when asked if the patient made any sense in his rambling calling outs.

And so our chapter ends with more questions added but no answers discovered.

Thoughts

The obvious questions I have is who is this sickly man? What is his connection to Jonas Chuzzlewit? What’s with all the numbers?

We know that Mrs Gamp is also tending to Chuffey who was the servant to Anthony and is now tending the home for Jonas Chuzzlewit. There is a connection being drawn by Dickens. What might it be?

There is much delightful humour with Mrs Gamp in this chapter. Why might Dickens have employed humour in this chapter? How effectively has Dickens counterbalanced the seriousness of a very ill man with the character and actions of Mrs Gamp?

Chapter 26

We open this chapter by meeting a man by the name of Paul Sweedlepipe, otherwise known as Poll Sweedlepipe, who is of much interest to me as he is a barber and a bird-fancier. How can one not enjoy a Dickens novel that has a bird, or two, or three, in it? He is Mrs Gamp’s landlord and we read that besides the staircase and Mrs Gamp’s private apartment his home “was one great bird’s nest.” On the staircases of his residence were rabbits, all sorts of rabbits. The combined odour of the birds and rabbits “saluted every nose” with a “complicated whiff.” Just imagine, Mrs Gamp and Sweedlepipe living in the same home. Surely this is one of Dickens’s great combinations of minor characters. In one paragraph Dickens manages to compare Poll to an eagle, hawk, sparrow, dove, pigeon, raven, robin, and shaved magpie.

One day Poll bumps into a young man wearing an impressive livery who turns out to be young Bailey from Todgers’s who is described as now having a “graceful rakishness.” We learn that he has left Todgers’s and is now employed by a gentleman whose face you can’t see for whiskers and you can’t see his whiskers for the dye upon them. Poll laments that with Bailey’s new-found position he would not want to buy another red-poll to which Bailey replies that he even considers a peacock to be vulgar.

We learn that Poll is in the process of escorting Mrs Gamp back to her rooms as she has been “superseded by another and more legitimate house-keeper: to wit, the gentleman’s bride.” The employer of Mrs Gamp is named Chuzzlewit. To this news Bailey recounts to Poll that he is well aware of Jonas Chuzzlewit boasting that Chuzzlewit and his bride almost “first kept company through me, a’most.”

Bailey and Poll arrive at the home of Jonas to find out from Gamp that the newlywed couple had not arrived yet. Bailey is surprised to learn that Jonas has married Merry and not Cherry. When the newlywed couple do arrive it takes Mrs Gamp but a second to notice that Merry does not seem merry at all. Indeed, there is a shade that pervades not only Merry but the whole house. The air is “heavy and oppressive; the rooms were dark; a deep gloom filled up every chink and corner” in the house even Chuff is described as “a creature of ill omen.” Not to miss any business opportunity, Mrs Gamp gives Merry a business card. Should Merry become pregnant, Mrs Gamp will be ready for Merry.

As the Chuzzlewit door closes Merry “felt a strange chill creep upon her” and is told by Jonas that the house will be “duller before you’re done with it.” She then obeys his command to order dinner. Chuffey asks her “You’re not married ... not married?” To her answer of yes Chuffey raises “his trembling hands above his head and laments “Oh! woe, woe, woe, upon this wicked house!” And so ends the chapter. Merry is no longer merry and the once briefly solicitous Jonas is now clearly the master of both the his house and Merry as well.

Chuffey interests me greatly. At the end of this chapter he calls the Chuzzlewit house “wicked.” Do you think he has always thought the house of Anthony Chuzzlewit wicked, even when Anthony was alive, or do you think his words are more directed towards what the house will be like now that Jonas is its owner?

Thoughts

This is a chapter of coincidences and transitions. What are the chances that Poll, Mrs Gamp’s landlord, would have once sold birds to Bailey who knows Jonas and Merry from Todgers’s who are now married? Do you love Dickensian coincidences as much as I do?

In terms of advancing the plot we see how miserably unhappy and dispirited Merry now is. What could have happen in the month since Jonas and Merry have become man and wife?

At the end of the chapter Chuffey seems concerned, resigned, and even fearful for the coming life of Merry. What does he know, or what do you think he suspects will occur in the coming weeks and months?

From Merry’s perspective, do you think she ever foresaw her life as one of a nursemaid to an ailing old man?

Reflections

Slowly but surely we are beginning to see how the seemingly separate characters and strands of this novel are beginning to braid themselves together. This week’s chapters have focussed on Jonas Chuzzlewit and the events, activities, and characters that occur in and around London. To what extent are you finding the two central plot locations of London and America difficult to follow? How might the experiences of Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley be linked to the events that are occurring in England?

We open this chapter by meeting a man by the name of Paul Sweedlepipe, otherwise known as Poll Sweedlepipe, who is of much interest to me as he is a barber and a bird-fancier. How can one not enjoy a Dickens novel that has a bird, or two, or three, in it? He is Mrs Gamp’s landlord and we read that besides the staircase and Mrs Gamp’s private apartment his home “was one great bird’s nest.” On the staircases of his residence were rabbits, all sorts of rabbits. The combined odour of the birds and rabbits “saluted every nose” with a “complicated whiff.” Just imagine, Mrs Gamp and Sweedlepipe living in the same home. Surely this is one of Dickens’s great combinations of minor characters. In one paragraph Dickens manages to compare Poll to an eagle, hawk, sparrow, dove, pigeon, raven, robin, and shaved magpie.

One day Poll bumps into a young man wearing an impressive livery who turns out to be young Bailey from Todgers’s who is described as now having a “graceful rakishness.” We learn that he has left Todgers’s and is now employed by a gentleman whose face you can’t see for whiskers and you can’t see his whiskers for the dye upon them. Poll laments that with Bailey’s new-found position he would not want to buy another red-poll to which Bailey replies that he even considers a peacock to be vulgar.

We learn that Poll is in the process of escorting Mrs Gamp back to her rooms as she has been “superseded by another and more legitimate house-keeper: to wit, the gentleman’s bride.” The employer of Mrs Gamp is named Chuzzlewit. To this news Bailey recounts to Poll that he is well aware of Jonas Chuzzlewit boasting that Chuzzlewit and his bride almost “first kept company through me, a’most.”

Bailey and Poll arrive at the home of Jonas to find out from Gamp that the newlywed couple had not arrived yet. Bailey is surprised to learn that Jonas has married Merry and not Cherry. When the newlywed couple do arrive it takes Mrs Gamp but a second to notice that Merry does not seem merry at all. Indeed, there is a shade that pervades not only Merry but the whole house. The air is “heavy and oppressive; the rooms were dark; a deep gloom filled up every chink and corner” in the house even Chuff is described as “a creature of ill omen.” Not to miss any business opportunity, Mrs Gamp gives Merry a business card. Should Merry become pregnant, Mrs Gamp will be ready for Merry.

As the Chuzzlewit door closes Merry “felt a strange chill creep upon her” and is told by Jonas that the house will be “duller before you’re done with it.” She then obeys his command to order dinner. Chuffey asks her “You’re not married ... not married?” To her answer of yes Chuffey raises “his trembling hands above his head and laments “Oh! woe, woe, woe, upon this wicked house!” And so ends the chapter. Merry is no longer merry and the once briefly solicitous Jonas is now clearly the master of both the his house and Merry as well.

Chuffey interests me greatly. At the end of this chapter he calls the Chuzzlewit house “wicked.” Do you think he has always thought the house of Anthony Chuzzlewit wicked, even when Anthony was alive, or do you think his words are more directed towards what the house will be like now that Jonas is its owner?

Thoughts

This is a chapter of coincidences and transitions. What are the chances that Poll, Mrs Gamp’s landlord, would have once sold birds to Bailey who knows Jonas and Merry from Todgers’s who are now married? Do you love Dickensian coincidences as much as I do?

In terms of advancing the plot we see how miserably unhappy and dispirited Merry now is. What could have happen in the month since Jonas and Merry have become man and wife?

At the end of the chapter Chuffey seems concerned, resigned, and even fearful for the coming life of Merry. What does he know, or what do you think he suspects will occur in the coming weeks and months?

From Merry’s perspective, do you think she ever foresaw her life as one of a nursemaid to an ailing old man?

Reflections

Slowly but surely we are beginning to see how the seemingly separate characters and strands of this novel are beginning to braid themselves together. This week’s chapters have focussed on Jonas Chuzzlewit and the events, activities, and characters that occur in and around London. To what extent are you finding the two central plot locations of London and America difficult to follow? How might the experiences of Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley be linked to the events that are occurring in England?

Chapter 24: griffins are very much dragon-like from what I see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Griffin

Which could give a very important explanation why Merry would marry Jonas despite her hating the guy, and warnings from Martin: money. She sees him as a being who gathered a lot of it, also through his father, and she connects money with status, and any social thing, even marriage, as a way of obtaining money, just like her dad taught her.

I did wonder at the grass for a moment, but did not realize how many grass-things there were in this chapter until you pointed it out. As I still have Rumpelstiltskin in mind after my comment about Quilp in another topic, and since we're in the realm of folk stories anyway, could it have something to do with spinning gold from straw? Something about expectation management perhaps?

Which could give a very important explanation why Merry would marry Jonas despite her hating the guy, and warnings from Martin: money. She sees him as a being who gathered a lot of it, also through his father, and she connects money with status, and any social thing, even marriage, as a way of obtaining money, just like her dad taught her.

I did wonder at the grass for a moment, but did not realize how many grass-things there were in this chapter until you pointed it out. As I still have Rumpelstiltskin in mind after my comment about Quilp in another topic, and since we're in the realm of folk stories anyway, could it have something to do with spinning gold from straw? Something about expectation management perhaps?

I certainly do love the coïncidences! I even wrote a sentence or two in my journal about Westlock making an appearance again. He seems to be some kind of glue who will glue some important pieces/characters together, but I might be wrong with that.

I also do wonder who the ill young man is. In chapter 26, which takes place a couple of weeks after the previous chapter (I do have the idea Jonas got his way in the end, a couple of weeks is not that long), nothing is said about him.

Gamp does not loose a business opportunity. I think she cannot afford to, especially now she loses a steady source of income from taking care of Chuffy. Imagine having to take up 24 hours of work a day to scrape by and perhaps save a little bit for when you don't have work ... and having to sleep on two chairs for that, as an somewhat elder person. As I said, she is very funny, but still also a bit sad. And reading these chapters I realized we're working our way towards this again with the gig economy we have now.

On the other hand, at least Gamp got paid for taking care of Chuffy, and can walk away from Jonas. That's more than Merry gets.

I also do wonder who the ill young man is. In chapter 26, which takes place a couple of weeks after the previous chapter (I do have the idea Jonas got his way in the end, a couple of weeks is not that long), nothing is said about him.

Gamp does not loose a business opportunity. I think she cannot afford to, especially now she loses a steady source of income from taking care of Chuffy. Imagine having to take up 24 hours of work a day to scrape by and perhaps save a little bit for when you don't have work ... and having to sleep on two chairs for that, as an somewhat elder person. As I said, she is very funny, but still also a bit sad. And reading these chapters I realized we're working our way towards this again with the gig economy we have now.

On the other hand, at least Gamp got paid for taking care of Chuffy, and can walk away from Jonas. That's more than Merry gets.

Jantine wrote: "Chapter 24: griffins are very much dragon-like from what I see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Griffin

Which could give a very important explanation why Merry would marry Jonas despite her hat..."

Jantine

Thank you for the link to Griffins. Their bodies are certainly suggestive of power (eagle and lion) and the Griffin’s association with money and wealth certainly fits as well. Pecksniff is always on the lookout for an extra pound or two, Jonas is portrayed as a man who will shrewdly barter for the best price, even for a bride, and both old Martin Chuzzlewit and his brother Anthony are men who have eagerly sought and kept their wealth. As has been mentioned before, this novel often pivots on the idea of money and greed.

The plucking of grass by Merry and the subsequent chewing of straw by Jonas struck me as important. Your idea makes sense to me. As well, could it be possible that Merry’s pulling of the grass is suggestive of a form of self-destruction, a pulling apart of her life? That Jonas would consume a piece of straw could suggest that he will consume Merry. Then there is the fact that to marry Merry is worth £5000. In Jonas’s mind that would be a good investment in business.

Marriage for love seems unimportant to Jonas. Like most Dickens novels, the reader will have to wait until the end of the novel to witness couples who marry for love and commitment rather than merely a financial transaction.

Which could give a very important explanation why Merry would marry Jonas despite her hat..."

Jantine

Thank you for the link to Griffins. Their bodies are certainly suggestive of power (eagle and lion) and the Griffin’s association with money and wealth certainly fits as well. Pecksniff is always on the lookout for an extra pound or two, Jonas is portrayed as a man who will shrewdly barter for the best price, even for a bride, and both old Martin Chuzzlewit and his brother Anthony are men who have eagerly sought and kept their wealth. As has been mentioned before, this novel often pivots on the idea of money and greed.

The plucking of grass by Merry and the subsequent chewing of straw by Jonas struck me as important. Your idea makes sense to me. As well, could it be possible that Merry’s pulling of the grass is suggestive of a form of self-destruction, a pulling apart of her life? That Jonas would consume a piece of straw could suggest that he will consume Merry. Then there is the fact that to marry Merry is worth £5000. In Jonas’s mind that would be a good investment in business.

Marriage for love seems unimportant to Jonas. Like most Dickens novels, the reader will have to wait until the end of the novel to witness couples who marry for love and commitment rather than merely a financial transaction.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 25

Peter wrote: "Chapter 25Do you think Dickens had any intention beyond humour in revealing that Mrs Harris is merely a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination? If so, what might that intention be?..."

Dickens revealing that Mrs Harris might be a figure of Mrs Gamp’s imagination is actually a bit disturbing. It’s no secret that Mrs Gamp is an alcoholic, but this repeated hallucination shows the severity of her condition.

But, placing this aside for a moment, I’m curious about what Mrs Harris might represent. Is she Mrs Gamp’s alter ego? Or does she serve another function entirely? We actually hear Mrs Gamp discuss Mrs Harris in chapter 19, long before we learn Mrs Harris is “a phantom of Mrs Gamp’s brain.”

Here is the first discussion I could find of Mrs Harris (chapter 19, p.303-304 in Penguin edition):

"'You have become indifferent since then, I suppose?’ said Mr Pecksniff. ‘Use is second nature, Mrs Gamp.’

‘You may well say second nater, sir,’ returned that lady. ‘One’s first ways is to find sich things a trial to the feelings, and so is one’s lasting custom. If it wasn’t for the nerve a little sip of liquor gives me (I never was able to do more than taste it), I never could go through with what I sometimes has to do. “Mrs Harris,” I says, at the very last case as ever I acted in, which it was but a young person, “Mrs Harris,” I says, “leave the bottle on the chimley-piece, and don’t ask me to take none, but let me put my lips to it when I am so dispoged, and then I will do what I’m engaged to do, according to the best of my ability.” “Mrs Gamp,” she says, in answer, “if ever there was a sober creetur to be got at eighteen pence a day for working people, and three and six for gentlefolks—night watching,”’ said Mrs Gamp with emphasis, ‘“being a extra charge—you are that inwallable person.” “Mrs Harris,” I says to her, “don’t name the charge, for if I could afford to lay all my feller creeturs out for nothink, I would gladly do it, sich is the love I bears ‘em. But what I always says to them as has the management of matters, Mrs Harris”’—here she kept her eye on Mr Pecksniff—‘"be they gents or be they ladies, is, don’t ask me whether I won’t take none, or whether I will, but leave the bottle on the chimley-piece, and let me put my lips to it when I am so dispoged.”’

TLDR; Mrs Harris praises Mrs Gamp, calling her services “invaluable.” Mrs Gamp uses this imaginary praise to promote her business and similarly later on, uses Mrs Harris in her flattery of the Moulds, which results in her obtaining a second job. The function of Mrs Harris seems self-serving, at this point. I’ll be interested to see if Mrs Harris continually acts in this role as the novel continues.

Emma wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 25

Do you think Dickens had any intention beyond humour in revealing that Mrs Harris is merely a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination? If so, what might that intention be?..."

..."

Emma

I too would like to know what exactly Dickens was up to with the comment that Mrs Harris is a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination. Was it for humour? To suggest the degree and depth of her drinking habits, to imply that she suffered from the DT’s, to set up an event or plot structure yet to come? My guess is it was for humour. We’ll see.

Do you think Dickens had any intention beyond humour in revealing that Mrs Harris is merely a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination? If so, what might that intention be?..."

..."

Emma

I too would like to know what exactly Dickens was up to with the comment that Mrs Harris is a figment of Mrs Gamp’s imagination. Was it for humour? To suggest the degree and depth of her drinking habits, to imply that she suffered from the DT’s, to set up an event or plot structure yet to come? My guess is it was for humour. We’ll see.

Big Chapter. Lots happened.

Wow!!! Good ol' Charity has no charity for Jonas or her sister, while sweet, sweet Mercy has no mercy for Charity. Virtue has its limits. The fight is on. Where's the popcorn?

So now we shall see what happens when two virtues come in conflict with one another. Do they annihilate each other, leaving only nihilism behind, or will we have a winner? Stay tuned.

-------------------

Old Martin has Jonas pegged.

---------------

We should not feel for Pecksniff. No good father would let Jonas marry his daughter after the way he has treated Charity and acted towards her father. Pecksniff deserves every bad thing coming to him. Does Mercy?

----------------

The way Jonas talked to Tom reveals his dead soul and savage heart. He is capable of anything. Poor Mercy will get no mercy from her husband. Will Charity show her sister charity when it's most needed? Stay tuned.

-----------------

You know, we may all like Tom and not like Old Martin calling him a toad, but Old Martin is right: Tom is Pecksniff's toad. Perhaps Tom needs someone like Old Martin telling him to stand up for himself more. And after seeing how he pops Jonas in the head, perhaps Tom has taken a little of what Old Martin has said to him to heart.

If Tom becomes more assertive, how will Mary see Tom? Interesting.

After listening to Old Martin's advice to Mercy, I can't help thinking he plays the role of elderly wisdom in this chapter.

Yes the transition from grass to straw was well done. A significant change in Dickens' writing from his first few novels? He's growing. The narrator is more sure of himself, becoming the center of gravity in these stories.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "

Big Chapter. Lots happened.

Wow!!! Good ol' Charity has no charity for Jonas or her sister, while sweet, sweet Mercy has no mercy for Charity. Virtue has its limits. The fight is on. Where's the..."

Xan

What a perfect summary of the major events that occurred in this week’s chapters. I need to take a lesson or two from you.

Big Chapter. Lots happened.

Wow!!! Good ol' Charity has no charity for Jonas or her sister, while sweet, sweet Mercy has no mercy for Charity. Virtue has its limits. The fight is on. Where's the..."

Xan

What a perfect summary of the major events that occurred in this week’s chapters. I need to take a lesson or two from you.

No, No.

No, No. Neither you nor Tristram can be replaced. Your summaries are detailed and thoughtful. Me, I'm just being irreverent. I can be that way with much of Dickens early stuff. I love his narrative voice. I get the feeling Dickens is beginning to believe his narrative voice can carry any story.

I trust you two save your chapter summaries some place other than on Goodreads.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "No, No.

Neither you nor Tristram can be replaced. Your summaries are detailed and thoughtful. Me, I'm just being irreverent. I can be that way with much of Dickens early stuff. I love his narrati..."

I agree neither Peter or Tristram can be replaced. Peter is a sweetheart and there is no one else grumpy enough to take Tristram's place. Well unless you want to take a shot at it, you're getting there.

Neither you nor Tristram can be replaced. Your summaries are detailed and thoughtful. Me, I'm just being irreverent. I can be that way with much of Dickens early stuff. I love his narrati..."

I agree neither Peter or Tristram can be replaced. Peter is a sweetheart and there is no one else grumpy enough to take Tristram's place. Well unless you want to take a shot at it, you're getting there.

Haha.

Haha.Sorry, but I have neither the wit nor the cleverness of Tristram to replace him as Grump #1. I prefer being his understudy.

There's no such thing as too many Grumps, as long as they've a kind of soft heart ;-)

I just thought about the grass again. If Mercy were the grass, she plucked herself first (with the gentlemen during the time at Todgers'), then she uprooted herself (by marrying Jonas). Jonas has her, in a different form than she was before, and now dead and dried up. And indeed, I believe he will eat and chew and break her now, but she is kind of dead already, because she's not herself anymore. I hope it makes sense ...

I just thought about the grass again. If Mercy were the grass, she plucked herself first (with the gentlemen during the time at Todgers'), then she uprooted herself (by marrying Jonas). Jonas has her, in a different form than she was before, and now dead and dried up. And indeed, I believe he will eat and chew and break her now, but she is kind of dead already, because she's not herself anymore. I hope it makes sense ...

Chapter 25

Chapter 25Mrs. Gamp. You sly devil!

My goodness, but Mr. Gamp had a drinking problem, as does his lovely wife, all of it so Dickens. And pinning the poor soul's arms to his sides so she could see how he'd look in a casket. Mould should double her pay. She'd be perfect in Arsenic and Old Lace; that is, when she isn't moonlighting as the Grim Reaper.

What a great chapter, and there is now a mystery to solve.

"Look about you," he said, pointing to the graves; "And remember that from your bridal hour to the day which sees you brought as low as these, and laid in such a bed, there will be no appeal against him."

Chapter 24

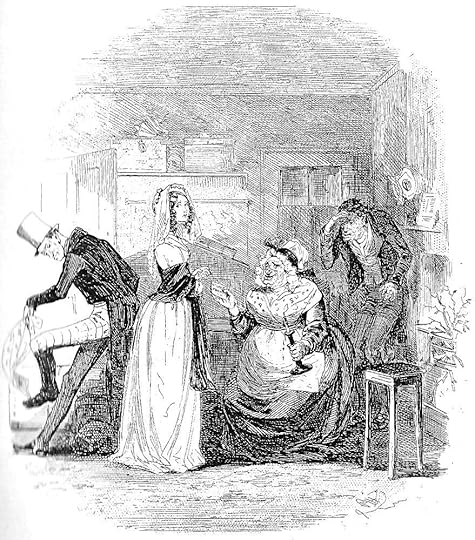

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘Then you don’t love him?’ returned the old man. ‘Is that your meaning?’

‘Why, my dear Mr Chuzzlewit, I’m sure I tell him a hundred times a day that I hate him. You must have heard me tell him that.’

‘Often,’ said Martin.

‘And so I do,’ cried Merry. ‘I do positively.’

‘Being at the same time engaged to marry him,’ observed the old man.

‘Oh yes,’ said Merry. ‘But I told the wretch—my dear Mr Chuzzlewit, I told him when he asked me—that if I ever did marry him, it should only be that I might hate and tease him all my life.’

She had a suspicion that the old man regarded Jonas with anything but favour, and intended these remarks to be extremely captivating. He did not appear, however, to regard them in that light by any means; for when he spoke again, it was in a tone of severity.

‘Look about you,’ he said, pointing to the graves; ‘and remember that from your bridal hour to the day which sees you brought as low as these, and laid in such a bed, there will be no appeal against him. Think, and speak, and act, for once, like an accountable creature. Is any control put upon your inclinations? Are you forced into this match? Are you insidiously advised or tempted to contract it, by any one? I will not ask by whom; by any one?’

‘No,’ said Merry, shrugging her shoulders. ‘I don’t know that I am.’

‘Don’t know that you are! Are you?’

‘No,’ replied Merry. ‘Nobody ever said anything to me about it. If any one had tried to make me have him, I wouldn’t have had him at all.’

Balm for the Wounded Orphan

Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Don’t make a noise about it," he said. "It’s nothing worth mentioning. I didn’t know the road; the night’s very dark; and just as I came up with Mr Pinch" — he turned his face towards Tom, but not his eyes — "I ran against a tree. It’s only skin deep."

"Cold water, Merry, my child!" cried Mr. Pecksniff. "Brown paper! Scissors! A piece of old linen! Charity, my dear, make a bandage. Bless me, Mr Jonas!"

"Oh, bother your nonsense," returned the gracious son-in-law elect. "Be of some use if you can. If you can’t, get out!" Miss Charity, though called upon to lend her aid, sat upright in one corner, with a smile upon her face, and didn’t move a finger. Though Mercy laved the wound herself; and Mr Pecksniff held the patient’s head between his two hands, as if without that assistance it must inevitably come in half; and Tom Pinch, in his guilty agitation, shook a bottle of Dutch Drops until they were nothing but English Froth, and in his other hand sustained a formidable carving-knife, really intended to reduce the swelling, but apparently designed for the ruthless infliction of another wound as soon as that was dressed; Charity rendered not the least assistance, nor uttered a word. But when Mr Jonas’s head was bound up, and he had gone to bed, and everybody else had retired, and the house was quiet, Mr Pinch, as he sat mournfully on his bedstead, ruminating, heard a gentle tap at his door; and opening it, saw her, to his great astonishment, standing before him with her finger on her lip.

Commentary: Tom plucks up a Spirit:

Phiz depicts Tom's coming to Jonas's aid, even though the sulky bully hardly deserves such kindness. Phiz could as easily have depicted Tom's unexpectedly thrashing Jonas for his insulting tone and unpleasant insinuations, but has chosen to show Tom exercising Christian forgiveness. Dickens and Phiz ironically describe Jonas as an "orphan" (a conventional subject for pity and concern) — although he may well be responsible for his father's death. The putting down of the bully here is as unexpected as Oliver's beating the viciously facetious Noah Claypole for insulting his dead mother in Oliver Plucks up a Spirit (April 1837).

Phiz has depicted the room in Pecksniff's house in the little Wiltshire village which serves as the backdrop for the action. We have seen it, decked out as a museum to likenesses of Pecksniff and his architectural drawings, before, in Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters (initial installment: January 1843), Mr. Pinch and The New Pupil on a Social Occasion (third installment: March 1843), and Mr. Pecksniff Renounces the Deceiver (fifth installment: May 1843). However, each instance seems to reveal another aspect of architectural conceptions of the designing architect — here, for example, images of churches (center, rear) have replaced those of engines, monuments, and a factory or poor house (Chapter VI, March 1843), as Tom lives the Christian message of forgiveness and charity, even to one's enemies.

"Whether I sicks or monthlies, Ma'am, . . . . I do require it"

Chapter 25

Fred Barnard

Dickens has Mrs. Gamp stipulate her terms of work, including regular service of alcoholic beverages, in order to underscore her bibulous nature and lax professional standards as a private nurse.

Text Illustrated:

Mr Mould winked at Mrs Mould, whom he had by this time taken on his knee, and said: ‘No doubt. A good deal more, Mrs Gamp. Upon my life, Mrs Gamp is very far from bad, my dear!’

‘There’s marryings, an’t there, sir?’ said Mrs Gamp, while both the daughters blushed and tittered. ‘Bless their precious hearts, and well they knows it! Well you know’d it too, and well did Mrs Mould, when you was at their time of life! But my opinion is, you’re all of one age now. For as to you and Mrs Mould, sir, ever having grandchildren—’

‘Oh! Fie, fie! Nonsense, Mrs Gamp,’ replied the undertaker. ‘Devilish smart, though. Ca-pi-tal!’—this was in a whisper. ‘My dear’—aloud again—‘Mrs Gamp can drink a glass of rum, I dare say. Sit down, Mrs Gamp, sit down.’

Mrs Gamp took the chair that was nearest the door, and casting up her eyes towards the ceiling, feigned to be wholly insensible to the fact of a glass of rum being in preparation, until it was placed in her hand by one of the young ladies, when she exhibited the greatest surprise.

‘A thing,’ she said, ‘as hardly ever, Mrs Mould, occurs with me unless it is when I am indispoged, and find my half a pint of porter settling heavy on the chest. Mrs Harris often and often says to me, “Sairey Gamp,” she says, “you raly do amaze me!” “Mrs Harris,” I says to her, “why so? Give it a name, I beg.” “Telling the truth then, ma’am,” says Mrs Harris, “and shaming him as shall be nameless betwixt you and me, never did I think till I know’d you, as any woman could sick-nurse and monthly likeways, on the little that you takes to drink.” “Mrs Harris,” I says to her, “none on us knows what we can do till we tries; and wunst, when me and Gamp kept ‘ouse, I thought so too. But now,” I says, “my half a pint of porter fully satisfies; perwisin’, Mrs Harris, that it is brought reg’lar, and draw’d mild. Whether I sicks or monthlies, ma’am, I hope I does my duty, but I am but a poor woman, and I earns my living hard; therefore I do require it, which I makes confession, to be brought reg’lar and draw’d mild.”’

The precise connection between these observations and the glass of rum, did not appear; for Mrs Gamp proposing as a toast ‘The best of lucks to all!’ took off the dram in quite a scientific manner, without any further remarks.

Mrs. Gamp, on the Art of Nursing

Chapter 25

Fred Barnard

Commentary:

Although Charles Dickens introduces us to one of his greatest comic creations, Mrs. Sarah ["Sairey"] Gamp, in the eighth instalment of the novel, illustrator Fred Barnard in his 1879 character sketch, completed seven years after his initial illustrations for the novel in the Household Edition, seems to be thinking of the divine Sairey as she appears in Chapter 25 because his caption, "Mrs. Gamp on the Art of Nursing," is thematically connected with that chapter's title: "Is in part professional; and furnishes the reader with some valuable hints in relation to the management of a sick chamber." So effective was Barnard's character study that Dana Estes, Boston, used it as the frontispiece for its fin-de-siecle edition of the novel: "Etched by S. A. Schoff — From a Drawing by Frederick Barnard".

Since Fred Barnard had read the whole of Martin Chuzzlewit in his formative years, when he created an extensive narrative-pictorial sequence for the novel in the new Chapman and Hall Household Edition of the 1872-790, he knew far more about the boozey medical attendant than Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) had when he illustrated the eighth instalment. Barnard's study post-dates both the composition of the story by some four decades and the professionalization of nursing by Florence Nightingale by a quarter of a century, so that he must have approached his subject in a manner very different from Phiz's when he did his first series of "Character Sketches from Dickens". To Dickens Mrs. Gamp had been a distinctive voice; Phiz, basing his image on Honoré Daumier's "Sick-room Nurse" ("La Garde-Malade") in the magazine Le Charivari, 22 May 1842, made her an overnight Victorian icon. Fred Barnard, working with both Dickens's text and Phiz's highly popular visualisation, had to synthesize everything he knew about Mrs. Gamp, including her appearances later in the novel and some four decades of her popular reception.

Although originally intended to be just a bit part, like a ham actor, a mere butt of Dickens's satire of drunken, disreputable nurses, Sairey consistently upstages the story's principals whenever she appears. Although she does not exactly "develop" as a character, she certainly blossoms. Although he has, according to the caption, seated her in Mr. Mould's parlour, Barnard has in fact situated her in her comfortable "chimley" corner. The illustrator crams into the study almost every visual detail associated with the bleery-eyed, husky-voiced, androgynous figure of capacious dimensions: the short, thick neck; the round face; the swollen nose (so forcibly anticipating that of W. C. Fields as the quintessence of the inveterate tippler); rusty black gown stained by snuff; oversize bonnet; bottle stationed on the mantelpiece; and, of course, her conspicuous umbrella or "gamp." Instead of showing her turning her eyes upward, as is her wont, Barnard has her thoughtfully gazing at the viewer, as if he or she is about to become the next client. Since Barnard has caught her in the moment when, her tea and pickled salmon finished, she wipes her mouth with a napkin of vaudeville dimensions, and we can be reasonably confident that the artist has realized the text just after this:

A tray was brought with everything upon it, even to the cucumber; and Mrs. Gamp accordingly sat down to eat and drink in high good humour.

Sairey Gamp

Chapter 25

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"Tell Mrs. Gamp to come upstairs," said Mould. "Now Mrs. Gamp, what's your news?"

The lady in question was by this time in the doorway, curtseying to Mrs. Mould. At the same moment, a peculiar fragrance was borne upon the breeze, as if a passing fairy had hiccoughed, and had previously been to a wine-vaults.

Mrs. Gamp made no response to Mr. Mould, but curtseyed to Mrs. Mould again, and held up her hands and eyes, as in a devout thanksgiving that she looked so well. She was neatly, but not gaudily attired, in the weeds she had worn when Mr. Pecksniff had the pleasure of making her acquaintance; and was perhaps the turning of a scale more snuffy.

"There are some happy creeturs," Mrs. Gamp observed, "as time runs back'ards with, and you are one, Mrs. Mould; not that he need do nothing except use you in his most owldacious way for years to come, I'm sure; for young you are and will be. I says to Mrs. Harris," Mrs. Gamp continued, "only t'other day; the last Monday evening fortnight as ever dawned upon this Piljian's Projiss of a mortal wale; I says to Mrs. Harris when she says to me, "Years and our trials, Mrs. Gamp, sets marks upon us all." — "Say not the words, Mrs Harris, if you and me is to be continual friends, for sech is not the case. Mrs. Mould," I says, making so free, I will confess, as use the name," (she curtseyed here), '"is one of them that goes agen the obserwation straight; and never, Mrs Harris, whilst I've a drop of breath to draw, will I set by, and not stand up, don't think it." — "I ast your pardon, ma'am," says Mrs. Harris, "and I humbly grant your grace; for if ever a woman lived as would see her feller creeturs into fits to serve her friends, well do I know that woman's name is Sairey Gamp."'

. . . . "My dear" — aloud again — "Mrs. Gamp can drink a glass of rum, I dare say. Sit down, Mrs Gamp, sit down."

Mrs. Gamp took the chair that was nearest the door, and casting up her eyes towards the ceiling, feigned to be wholly insensible to the fact of a glass of rum being in preparation, until it was placed in her hand by one of the young ladies, when she exhibited the greatest surprise. — Chapter 25

Commentary:

Over the course of a number of illustrated editions of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit a number of versions of the novel's bibulous sick-room nurse, Mrs. Sarah Gamp (whose name derives from her umbrella) appeared, by Hablot Knight Browne, Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Sol Eytinge, Jr., Fred Barnard, and Harry Furniss. However, all of these are based on the original conception by Phiz, to which Clayton J. Clarke paid tribute in his series of Dickens illustrations for Players' Cigarette cards in 1910. Furniss's interpretation is slightly more animated and less cartoonish than the Phiz original, which in turn was based on Honoré Daumier's "Sick-room Nurse" ("La Garde-Malade") in the Paris magazine Le Charivari, 22 May 1842, made her an overnight Victorian icon. Fred Barnard, working with both Dickens's text and Phiz's highly popular visualisation, had to synthesize everything he knew about Mrs. Gamp, including her appearances later in the novel and some four decades of her popular reception, a synthesis upon which such later illustrators as Kyd and Furniss based their interpretations.

Perhaps nowhere else in Phiz's narrative-pictorial sequence for the initial serialization of Martin Chuzzlewit is the illustrator's imagination so stimulated by the letterpress, with the result that Phiz describes not merely the outward and visible signs of the two sick-room nurses in Mrs. Gamp Proposes a Toast (June 1844), but also captures their milieu and ultimately the essence of the immortal Sairey herself. Every detail from Dickens's letterpress is present, and is depicted in proper relation to every other object, right down to the central object not merely of the room but of Sairey's inner life, the convivial teapot, the sacred chalice under whose influence Sairey's alcohol-tinged syllables take flight into the aether of world literature. She is here, like her visual and verbal creators, a great inimitable, doubled by the dresses that like angelic facsimile Saireys hover above their original. Whereas Fred Barnard incorporates all of these elements into his 1879 portrait of the inimitable Sairey for Character Sketches from Dickens, Harry Furniss, like Kyd and Eytinge, focuses on her person and does not supply contextual details. That she is sitting down rather than standing and is holding a small glass points to the passage in which Mr. Mould, the undertaker, offers her some rum punch in Chapter 25.

The classic image of Mrs. Gamp, taking a little something against the cold, remains Barnard's 1872 frontispiece "Mrs. Gamp, on the Art of Nursing", in which she contemplates her gigantic bonnet; Barnard has included her umbrella (from which she takes the surname "Gamp") and the proverbial bottle on the chimbley-piece, ready to hand. Here we see the direct origins of the Furniss illustrations of Mrs. Gamp.

Mrs. Gamp Has Her Eye on the Future

Chapter 26

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

No," said Merry, almost crying. "You had better go away, please!" With a leer of mingled sweetness and slyness; with one eye on the future, one on the bride, and an arch expression in her face, partly spiritual, partly spirituous, and wholly professional and peculiar to her art; Mrs Gamp rummaged in her pocket again, and took from it a printed card, whereon was an inscription copied from her signboard.

“Would you be so good, my darling dovey of a dear young married lady,” Mrs. Gamp observed, in a low voice, “as put that somewheres where you can keep it in your mind? I’m well beknown to many ladies, and it’s my card. Gamp is my name, and Gamp my nater. Livin’ quite handy, I will make so bold as call in now and then, and make inquiry how your health and spirits is, my precious chick!” [Chapter XXVI, "An Unexpected Meeting, and a Promising Project," descriptive headline in the 1867 edition and in Volume 2 of the 1897 edition: "Woo'd and Married and A'."

Commentary: Unhappy Newly-wed:

Dickens's descriptive headline, added in a late revision to the novel, offers a note of finality to Mrs. Gamp's ministrations to Chuffey and Mercy Chuzzlewit's chances for a happy marriage. Jonas appears to mean that Chuffey has gotten over his old master's death, and that he therefore can be superintended from now on by the new Mrs. Chuzzlewit, the former Mercy Pecksniff. However, his intention is to make sure that nobody from outside the immediate family is about the house to garner any information about Anthony's sudden demise. In the well-known Scottish lyric "Wood'd and Married and a'" (No. 7 in her Songs), Joanna Baillie (1762-1851) uses the line as refrain for a description of a young and beautiful bride who harbours some secret grief:

The Bride she is winsome and bonny,

Her hair it is snooded sae sleek,

And faithfu' and kind is her Johnny,

Yet fast fa' the tears on her cheek.

New pearlins are cause of her sorrow,

New pearlins and plenishing too,

The bride that has a' to borrow,

Has e'en right mickle ado,

Woo'd and married and a'!

Woo'd and married and a'!

Is na' she very weel aff

To be woo'd and married at a?

The refrain, which appears as a descriptive headline adjacent to the illustration, implies that Merry will repent her bargain, and very soon will deeply regret she marrying such a bully. The illustration demonstrates that Jonas has greater regard for the shine on his boots rather than the happiness of his young wife, whom he has brought to the verge of tears.

Phiz's interpretation of "an eye to the future" in the plate's title encompasses both Merry and Sairey. As Mrs. Gamp presents her midwife's card, the young Mrs. Chuzzlewit seems to appeal to the reader for sympathy. Thus, the blighted plant in the fireplace may well symbolize Merry's future as a much put-upon wife and mother. Her anxious look betokens, then, trepidation as to what kind of future she can expect, married to such a brute, and Chuffey's anguish may reflect his concern for her rather than grief over his master's death. Mrs. Gamp's apparently limits her prognostication to Mercy's becoming a mother over the course of the coming year. In the stilted language of business, Merry will prove a "promising project" for the midwife, if not for an undertaker.

The Genesis of the Divine Sairey:

The somewhat cluttered design of Mrs. Gamp has her Eye on the Future underscores the arrival of the novel's chief comic character, Sairey Gamp. Although Dickens may not have seen Honoré Daumier's La Garde-Malade in the 22 May 1842 issue of the Paris magazine of topical commentary and humour Le Charivari, Phiz almsy certainly had, for the decrepit image of the French sick-room nurse bears a strong resemblance to the various Phiz illustrations involving Sairey Gamp. Dickens's inspiration, contends Goldie Morgentaler, lay closer to home:

The character was inspired by the nurse of a friend of Angela Burnett Coutts, who had a habit of running her nose along the fender. Dickens confers the same habit on Mrs. Gamp (see ch. 25). At a time when home nursing was the rule, Dickens's portrayal of the snuff-taking, cucumber-loving, gin-swilling, money-grubbing, callous Sarah Gamp gave home nurses a bad name, and, Anne Summers suggests, contributed to the masculinization of the medical profession.

Here is the illustration by Daumier:

The Sickroom Nurse (La Garde-Malade)

Honoré Daumier (1808-79)

22 May 1842

Daumier and Phiz:

In Victorian Novelists and Their Illustrators (1970), John Harvey convincingly argues that in completing the research for a commission for the illustrations an English novel three years earlier Phiz would have encountered the work of French lithographer and cartoonist Honoré Daumier. In particular, Harvey notes the similarity between Phiz's handling of Sairey Gamp's distinctive visage and Daumier's use of fine lines to convey subtle facial expressions in the caricatures of financier Robert Macaire and his assistant Bertrand:

In 1840 Browne illustrated [George W. M.] Reynolds' novel Robert Macaire in England [London : Thomas Tegg, 3 vols.]. Macaire, the principal character in a French farce, L'Auberge des Adrets, had been taken over by Daumier and made the protagonist in a long series of caricatures in the 1830s. Reynolds' hero is related only loosely to his French sources, and Browne could have illustrated the novel without turning up Daumier's series; yet his version of the arch-swindler Macaire and his assistant Bertrandis clearly based on Daumier's. In particular, he has taken over the very fine lines of facial expression that characterize Daumier's two rogues.

In the Chuzzlewit plates the influence of Daumier can be detected in a characteristic way of rendering eyelids and eyebrows, but the clearest proof of the connection is to be found in the studies of Sarah Gamp. . . , who closely resembles Daumier's sick-nurse . . . of 1842. In both of Browne's etchings Sarah's head is seen from the same angle as the other nurse's, is drawn in the same style, and has the same features, down to he cleft in the chin. From Daumier, Browne acquired a new fertility and fineness in the witty touching in of faces; many of the Chuzzlewit plates are crowded, but each face in the crowd is an individual study. Earlier plates like 'The Trial ' [March 1837] had been packed with comic individuals, but the Chuzzlewit plates show a more generous sense of the range and substance of individuality.

It is quite possible, given his interest in the periodical press, that Dickens himself had seen and been directly influenced by Daumier's caricature, either in a copy of the Paris magazine or in a clipping at Browne's.

"There's nothin' he don't know, that's my opinion,"

Chapter 26

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Paul knocked at Jonas Chuzzlewit’s; and, on the door being opened by that lady, made the two distinguished persons known to one another. It was a happy feature in Mrs Gamp’s twofold profession, that it gave her an interest in everything that was young as well as in everything that was old. She received Mr Bailey with much kindness.

‘It’s very good, I’m sure, of you to come,’ she said to her landlord, ‘as well as bring so nice a friend. But I’m afraid that I must trouble you so far as to step in, for the young couple has not yet made appearance.’

‘They’re late, ain’t they?’ inquired her landlord, when she had conducted them downstairs into the kitchen.

‘Well, sir, considern’ the Wings of Love, they are,’ said Mrs Gamp.

Mr Bailey inquired whether the Wings of Love had ever won a plate, or could be backed to do anything remarkable; and being informed that it was not a horse, but merely a poetical or figurative expression, evinced considerable disgust. Mrs Gamp was so very much astonished by his affable manners and great ease, that she was about to propound to her landlord in a whisper the staggering inquiry, whether he was a man or a boy, when Mr Sweedlepipe, anticipating her design, made a timely diversion.

‘He knows Mrs Chuzzlewit,’ said Paul aloud.

‘There’s nothin’ he don’t know; that’s my opinion,’ observed Mrs Gamp. ‘All the wickedness of the world is Print to him.’

Mr Bailey received this as a compliment, and said, adjusting his cravat, ‘reether so.’

‘As you knows Mrs Chuzzlewit, you knows, p’raps, what her chris’en name is?’ Mrs Gamp observed.

‘Charity,’ said Bailey.

‘That it ain’t!’ cried Mrs Gamp.

‘Cherry, then,’ said Bailey. ‘Cherry’s short for it. It’s all the same.’

‘It don’t begin with a C at all,’ retorted Mrs Gamp, shaking her head. ‘It begins with a M.’

‘Whew!’ cried Mr Bailey, slapping a little cloud of pipe-clay out of his left leg, ‘then he’s been and married the merry one!’

Chapter 26

Chapter 26Yea!!! BAILEY IS BACK.

I'm so happy Bailey is back I don't care that he returns by falling over someone in London.

Will Bailey save mercy from Jonas and take her as his own wife?

The return of Bailey reminds me of a recurring problem I have with Dickens, and that is the changing age of his young characters. When we first met Bailey I'd thought he was about 12 or 13. Now I think he's old enough to stand up to Jonas. The same was true with Nell and NN to some extent.

I forgot to include Merry Mercy. When we first meet her she is sitting in her father's lap, and from that and other clues come to believe she is too young for marriage. Yet here she is married to Jonas. What's her age?

I forgot to include Merry Mercy. When we first meet her she is sitting in her father's lap, and from that and other clues come to believe she is too young for marriage. Yet here she is married to Jonas. What's her age?

Kim wrote: "

Kim wrote: ""Look about you," he said, pointing to the graves; "And remember that from your bridal hour to the day which sees you brought as low as these, and laid in such a bed, there will be no appeal agai..."

This is such a peculiar scene to try to visualize. I think he did a pretty good job illustrating it.

Peter wrote: "I can’t help but see the exchange between Merry and old Martin as having great significance to the novel. The question is, what significance?

Peter wrote: "I can’t help but see the exchange between Merry and old Martin as having great significance to the novel. The question is, what significance?Jantine wrote: a very important explanation why Merry would marry Jonas despite her hating the guy, and warnings from Martin: money. She sees him as a being who gathered a lot of it, also through his father, and she connects money with status, and any social thing, even marriage, as a way of obtaining money, just like her dad taught her….

On the other hand, at least Gamp got paid for taking care of Chuffy, and can walk away from Jonas. That's more than Merry gets.

"

Merry makes even less sense to me as a character than Mark. I can't really figure out what kind of moral failing she's supposed to be warning us about. Capriciousness?

But Martin Senior's conversation here suggests all the more to me that he is playing a Deep Game. I get the impression he is trying to avoid seeing Merry fall prey to whatever he's planning for his male relatives, but finally gives her up as hopeless, rather than give up his game which is so entertaining to his miserly wizened heart.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 26

Yea!!! BAILEY IS BACK.

I'm so happy Bailey is back I don't care that he returns by falling over someone in London.

Will Bailey save mercy from Jonas and take her as his own wife?

The..."

Yes, Xan, I had the same impression with Little Nell, and to an even stronger degree, with Kit Nubbles, who also turns from a dim-witted comic relief character into something of a hero.

In Bailey's case, however, I think that part of the fun we have with this character results from the fact that he is a boy acting too mature for his age. His self-confidence and precociousness may even impress other people so much that he gets away with it.

Yea!!! BAILEY IS BACK.

I'm so happy Bailey is back I don't care that he returns by falling over someone in London.

Will Bailey save mercy from Jonas and take her as his own wife?

The..."

Yes, Xan, I had the same impression with Little Nell, and to an even stronger degree, with Kit Nubbles, who also turns from a dim-witted comic relief character into something of a hero.

In Bailey's case, however, I think that part of the fun we have with this character results from the fact that he is a boy acting too mature for his age. His self-confidence and precociousness may even impress other people so much that he gets away with it.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "...Merry Mercy. When we first meet her she is sitting in her father's lap, and from that and other clues come to believe she is too young for marriage. Yet here she is married to J..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "...Merry Mercy. When we first meet her she is sitting in her father's lap, and from that and other clues come to believe she is too young for marriage. Yet here she is married to J..."Xan - there are a lot of women sitting on men's laps in Dickens. Mrs. Mould sits on Mr. Mould's lap while talking to Mrs. Gamp. Bella Wilfer sits on her father's lap. I believe there was some lap sitting in "Pickwick" and "A Christmas Carol" (though the latter may have been in film, if not the novel). Was it really that common in Victorian England, or just a bit of a fetish for Dickens? I don't recall it being mentioned by other authors of the time. Maybe there was a chair shortage. Hmm....

"Sairey Gamp Chapter 25 Harry Furniss

"the novel's bibulous sick-room nurse, Mrs. Sarah Gamp (whose name derives from her umbrella) ..."

I always thought that "gamp" became a synonym for umbrella based on Sarah's character, who always had one with her. This commentary seems to say that "gamp" was already a synonym for umbrella, and that's why Dickens chose it for her name. Which came first, the gamp or the Gamp? Does anyone still use the word in England? I'm sure if I told everyone I knew to grab their gamps in case of rain, 99% of them wouldn't have a clue as to what I was talking about.

I, too, was delighted to see Bailey return. He's a breath of fresh air in a novel filled with sick rooms and misery.

I love the symbolism of Chuzzlewit discussing Merry's future with her in the cemetery. You all picked up beautifully on the grass symbolism, which I completely missed. Nicely done.

It was surprising to me that no one else mentioned the similarities between the scene at the Mould's home prior to the arrival of Mrs. Gamp, with a similar scene with the Sowerberrys in Oliver Twist - Mr. Sowerberry, you'll recall, was also an undertaker. It was like déjà vu when I read it! At first I wondered if I was just remembering it from my first reading of Chuzzlewit, but it seemed much too recent for that. Then I realized it was Twist I was thinking of. Does anyone else remember the passage I'm referring to? I did a quick scan of OT, but didn't immediately find it.

Mrs. Harris is one of my favorite Dickens characters! She's the forerunner for memorable TV characters like Hyacinth Bucket's son, Sheridan on Keeping Up Appearances, Carlton the doorman from Rhoda, Maris Crane on Frasier, and many others whom we never actually see. I wonder if Dickens created the "unseen character" or if there are other, earlier examples. All are better left to our imaginations. Genius.

And Mrs. Prig's beard! That line threw me for a loop! Like Peter said, just casually tossed out with no ado. I have a pen and ink illustration of Sarah and Mrs. Prig that I found in an antique store and framed, which hangs on the wall near me now. I took a close look at it and, regrettably, the artist didn't include Betsy's beard. Just a few subtle chin hairs would have been perfect. :-)

Finally, would anyone like to speculate as to why Dickens never names the horse that Bailey is tending?

The horse of distinguished family, who had Capricorn for his nephew, and Cauliflower for his brother...

But we never learn this horse's name. He's always referred to as "Cauliflower's brother". I can't imagine that the horse plays a big enough role in the plot that would require that his name be kept secret à la the bachelor in The Old Curiosity Shop. Most peculiar. We can speculate that his name starts with the letter C. Calliope? Caramel? Calcutta? Cicero? Confederate? If he's named in future chapters, please feel free to spoil it for me! I'm dying to know. :-)

Here's the illustration of Sarah and Betsy that I referenced in the preceding comment, for anyone who's interested. I think I paid $7-8 for it, unframed. I was delighted! The friend who was with me at the time was tolerant, if bemused. She did not understand, let alone share, my glee.

Here's the illustration of Sarah and Betsy that I referenced in the preceding comment, for anyone who's interested. I think I paid $7-8 for it, unframed. I was delighted! The friend who was with me at the time was tolerant, if bemused. She did not understand, let alone share, my glee. https://www.goodreads.com/photo/user/...

Let's say the left figure is Prig, because the right one is exactly how I imagine Sairey Gamp to be. That illustration, combined with the beard, at once made me wonder why Prig would choose the hard life of dressing up as a woman in this era. And I wonder, would that happen?

Mary Lou wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "...Merry Mercy. When we first meet her she is sitting in her father's lap, and from that and other clues come to believe she is too young for marriage. Yet here she is mar..."

Mary Lou

You are motoring right along. Thanks for reminding us of other “unseen characters.” I have no idea if Dickens begin this trend. In Shakespeare there are incidences where ghosts are “seen?” but that is of another nature. Great question.

Mary Lou

You are motoring right along. Thanks for reminding us of other “unseen characters.” I have no idea if Dickens begin this trend. In Shakespeare there are incidences where ghosts are “seen?” but that is of another nature. Great question.

Jantine wrote: "Let's say the left figure is Prig, because the right one is exactly how I imagine Sairey Gamp to be. That illustration, combined with the beard, at once made me wonder why Prig would choose the har..."

Ha, I just left a comment with Mary Lou under her photo which was to the same effect. Shall we have a poll on who is Mrs. Gamp? :-)

Ha, I just left a comment with Mary Lou under her photo which was to the same effect. Shall we have a poll on who is Mrs. Gamp? :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "

Mrs. Harris is one of my favorite Dickens characters! She's the forerunner for memorable TV characters like Hyacinth Bucket's son, Sheridan on Keeping Up Appearances, Carlton the doorman from Rhoda, Maris Crane on Frasier, and many others whom we never actually see. I wonder if Dickens created the "unseen character" or if there are other, earlier examples. All are better left to our imaginations. Genius."

I like to think that Dickens invented the unseen character. In Mrs. Gamp's case we might even be quite sure that the often referred-to Mrs. Harry is probably a figment of her imagination merely. A different, but also very well-known case is Mrs. Columbo: I always thought that Columbo only made her up in order to puzzle his suspects but then there was an episode when he had his wife on the phone. So that question is settled.

Mrs. Harris is one of my favorite Dickens characters! She's the forerunner for memorable TV characters like Hyacinth Bucket's son, Sheridan on Keeping Up Appearances, Carlton the doorman from Rhoda, Maris Crane on Frasier, and many others whom we never actually see. I wonder if Dickens created the "unseen character" or if there are other, earlier examples. All are better left to our imaginations. Genius."

I like to think that Dickens invented the unseen character. In Mrs. Gamp's case we might even be quite sure that the often referred-to Mrs. Harry is probably a figment of her imagination merely. A different, but also very well-known case is Mrs. Columbo: I always thought that Columbo only made her up in order to puzzle his suspects but then there was an episode when he had his wife on the phone. So that question is settled.

A fictional character who creates a fictional character. I wonder who Mrs. Harris creates in the middle of the night? Us?

A fictional character who creates a fictional character. I wonder who Mrs. Harris creates in the middle of the night? Us?

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "A fictional character who creates a fictional character. I wonder who Mrs. Harris creates in the middle of the night? Us?"

Hang on - I'll have to fortify myself with a dram from that bottle on the chimley-piece that is normally reserved for Mrs. Gamp, in order to follow and digest that thought!

Hang on - I'll have to fortify myself with a dram from that bottle on the chimley-piece that is normally reserved for Mrs. Gamp, in order to follow and digest that thought!

Greetings Curiosities

Chapter 24 brings us back to England, specifically to Mr Pecksniff’s front door. There is no question that Jonas Chuzzlewit is the alpha male in Pecksniff’s own home. Pecksniff jumps at Jonas’ demand that the door be opened immediately. In order to feel that he has some control in his own house Pecksniff then orders Tom Pinch to go to his daughters’ room and announce the arrival of Martin Chuzzlewit senior and Mary. Pecksniff then prepares himself for his visitors and casually greets them with a tone of false humility and excessive flattery. Old Chuzzlewit, in turn, tells Mary that “flattery from [Pecksniff] is worth the having. He is not a dealer in it, and it comes from his heart.” Old Chuzzlewit seems somewhat more mellow than in earlier chapters when he comments on the loss of his brother, on how they had been strangers for years, and wishes “Peace to his memory.”

Pecksniff tells old Martin that his brother called out to him in his last days to “come to me.” Pecksniff furthers his comments by saying he sat by Anthony’s bed and stood beside his grave. All these facts are true. It is interestIng to reflect on how Pecksniff is, in fact, telling the truth in these words and yet as readers we know there is a subtext that exists in the recent events and death of Anthony Chuzzlewit. Speaking of Jonas Chuzzlewit, old Martin says

My brother had in his wealth the usual doom of wealth, and root of misery. He carried his corrupting influence with him, go where he would; and shed it around him, even on his hearth. It made of his own child a greedy expectant, who measured every day and hour the lessening distance between his father and the grave, and cursed his tardy progress on that dismal road.”

Thoughts

I find the above quotation from old Martin a key comment in terms of character development, irony, foreshadowing, and plot.

How does the quotation reinforce or develop the character of old Martin?

Do you see any irony in the comment?

How might these words form or suggest what may happen later in the novel?

To what extent do you think old Martin has softened in his outlook on the world from the first time you met him in the novel?

Is it possible that old Martin is insincere in his apparent softened view on the world?

Pecksniff tells Martin that Jonas is now in his home “seeking in change of scene the peace he has lost.” To reinforce his comments, Pecksniff refers to the way Jonas mourned the loss of his father and suggests that Mrs Gamp was a close witness to the recent suffering of Jonas. Pecksniff then sheds a few “tears of honesty” at the end of his spirited defence of Jonas. Upon learning that Jonas is now in Pecksniff’s house, Martin demands to see him. The meeting has its edges. Jonas tells his uncle that he has been “as good a son as ever you were a brother. It’s the pot and the kettle, if you come to that.” The nephew and uncle shake hands, but I feel their relationship is still on shaky ground.

Adding to the sharp edges of the evening is the “unspeakable jealousy and hatred ... sown in Charity’s breast.” Poor Pecksniff - should we feel sorry for him? - he has to balance the attitude of Jonas, the friction between his two daughters, his dislike of Tom Pinch, and his conciliation with old Martin all at the same time. Old Martin then wants to go to the Green Dragon and asks for Tom Pinch to lead the way. Ah Tom. He gets to have Mary Graham take his arm.

On the way to the Dragon old Martin questions Tom about his knowledge of Jonas and learns that Tom never spoke to him before this evening. Old Martin sees Tom as being little more than a “zealous ... toad-eater.” On his way back from the Dragon, Tom encounters Jonas who tells Tom that “you haven’t a right to anything.” Tom attempts to be civil, but his words seem only to inflame Jonas even more. Jonas wants to know more about Martin Chuzzlewit junior. With that, Jonas flourishes a stick over Tom’s head but Tom, in defending himself, manages to hit Jonas in the head and make a deep cut into his temple. Jonas gives Tom a look that clearly shows this injury will not be forgotten.

Thoughts

All is not well in the Pecksniff home. Why do you think Pecksniff attempts to defend Jonas to old Martin?

How could the attitude of Jonas towards his uncle create more conflict later in the novel?

Did you feel much sympathy in Pecksniff’s discomfort and attempts to smooth over the various animosities that were brewing in his home?

Poor Tom Pinch. His retiring and honest character seems to aggravate old Martin Chuzzlewit, anger Jonas Chuzzlewit, and suggest to Mary that he was “not remarkable for presence of mind.” What might Dickens be up to with this further development and revelation of Tom’s character and personality? Has this chapter changed your opinion of Tom?

Upon returning to Pecksniff’s home Mercy sees the blood on Jonas and tends to him. Charity just sits there “with a smile on her face and didn’t move a finger.” When Tom goes to bed a tap comes to his door. It is Charity who had never spoken to Tom kindly in all his years in the Pecksniff house. When she learns that it was Tom who wounded Jonas she says “[D]ear Mr Pinch, I am your friend from to-night. I am always your friend from this time.” With that she takes Tom’s hand, presses it to her breast, and kisses it. Tom goes to bed, feels horribly guilty, believes he has betrayed Pecksniff’s trust, and then dreams of Mary Graham.

Thoughts

I’m not sure whether to cheer for or feel sorry for Tom. He has delivered a blow to the ego and over-bearing personality of Jonas, created a friend in Charity, increased his guilt about his actions towards Pecksniff, and dreamed about Mary. Let's see now ...

Tom has made an enemy in Jonas. How might this fact become increasing important as the novel progresses?

Charity, through her joy of Tom causing pain to Jonas, has become a friend of Tom’s. How can this possibly be a good thing, or could it make even more trouble for Tom?

Tom has a dream of Mary Graham. Hmmm, any Freudian speculation?

Tom and Mary continue to be together in the following days at Pecksniff’s. It appears that only through the playing of music does Tom Pinch find any peace and contentment. No news or conversation about young Martin Chuzzlewit passes between Tom and Mary.