The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 27-29

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 28

This chapter starts with insight provided for us by the omniscient narrator on why Jonas is inclined to accept Montague’s offer. One of his reasons for feeling attracted by it is that ”the money [to be made] had the peculiar charm of being sagaciously obtained at other people’s cost.” Jonas is also inveigled by the prospect of ”homage and distinction” he will get in his new position. Finally, the narrator summarizes,

Still under the influence of all these future gains, both in money and in power, Jonas knocks at Montague’s door in Pall Mall the next day, and the door is opened by Bailey, Junior, who greets Jonas with some amount of familiarity, knowing him for the man who courted the Pecksniff girls – one can’t but use the plural here – at Todgers’s. Jonas may be annoyed by this, but he doesn’t pay a lot of heed to the young man. When he is received by Montague, he finds himself in the presence of the Chairman himself, Mr. Crimple, Dr. Jobling and two other gentlemen, Messrs Pip and Wolf, whose task it seems to be to talk so much of the social circles which will now open themselves to Jonas as to make his head quite dizzy. Apart from that, the wine that is being served, and that Jonas has liberal recourse to, seeing that he does not have to pay for it, adds to the dizziness invading our friend’s brain. During the extremely sumptuous meal – Montague makes a point of stressing that a meal like that is a daily luxury for him, well, not nearly a luxury at all – Jonas is more and more impressed by the lifestyle he witnesses, and since it also becomes clear that he himself will not be expected to go to similar expenses, it being Montague’s duty, and pleasure, to represent the company by standing treat to visitors and customers, so that Jonas himself can salt away all his profits, it is just a matter of time before Jonas is fully entangled in the web laid out by the wily Montague. In the course of the dinner, the wine flows more and more freely, and Jonas is becoming drunker and drunker, more and more displaying the despicable and cur-like aspects of his character, e.g. by openly showing his contempt for Montague’s lavishness in spending while enjoying all the profusion to the utmost. Montague, however, takes no umbrage at this thankless behaviour because, apparently, he knows that eventually he will have the upper hand over Jonas.

When, later in the evening, Crimple asks his friend whether Jonas is hooked, Montague replies that he is, with a very strong iron. By this time, it being around three o’ clock in the morning, Jonas has drunk himself into a sodden stupor, and Montague orders Bailey to take that gentleman home. The young sprite exerts his order as best he can, treating the half-asleep Jonas more like an unwieldy portmanteau than like a person, and when he finally arrives at Jonas’s house and rings the bell, he finds that Merry has been waking up for her husband. However, when he spies through the keyhole and sees her advance towards the door, what he sees is this:

Recognizing Bailey, a hint of her old merry self comes to her face, but that is only short-lived – so much so that it brings tears into Bailey’s eyes. He calms her down, or tries so, by saying that her husband is just a little inebriated, and then he helps Jonas into the house, witnessing the attempts on Merry’s part to soothe the grumpy temper of her husband, while Jonas, in his drunkenness – but he would also have done so in his sobriety, so much is clear – hurls various curses and invectives at her, calling he a clog tied to him, who could have risen even higher without her, and a ”mewling, white-faced cat”, which I didn’t find very nice, but rather original. He also shows that he means to pay back her former humiliations of him, when he says,

But Bailey has left by now, because Merry entreated him to do so, and so the boy also fails to witness when Jonas sinks even lower by beating his wife.

QUESTIONS

What do you think of this chapter? I must confess that the first part of it seemed like a rehash of Chapter 27, and that Pip and Wolf with all their talk, tired my patience a bit. They reminded me of Pyke and Pluck in a way, and they clearly were invited by Montague with a view of getting Jonas deeper into the spider’s web.

What do you think of Merry’s change? Is it believable? It’s not too long ago since we last saw her enter her new home, and already she is quite a different woman. Can this happen so quickly?

Do you think Pecksniff knows what kind of life his daughter is led? If he did so, would he intervene?

Despite the violence and scorn Merry experiences from Jonas, she seems bent on propitiating him and on conquering him by kindness. What do you think of this? And, since I think this is the author’s idea(l) of womanhood interfering, what do you think of the close of the chapter, when the narrator says,

This chapter starts with insight provided for us by the omniscient narrator on why Jonas is inclined to accept Montague’s offer. One of his reasons for feeling attracted by it is that ”the money [to be made] had the peculiar charm of being sagaciously obtained at other people’s cost.” Jonas is also inveigled by the prospect of ”homage and distinction” he will get in his new position. Finally, the narrator summarizes,

”The latter considerations were only second to his avarice; for, conscious that there was nothing in his person, conduct, character, or accomplishments, to command respect, he was greedy of power, and was, in his heart, as much a tyrant as any laureled conqueror on record.”

Still under the influence of all these future gains, both in money and in power, Jonas knocks at Montague’s door in Pall Mall the next day, and the door is opened by Bailey, Junior, who greets Jonas with some amount of familiarity, knowing him for the man who courted the Pecksniff girls – one can’t but use the plural here – at Todgers’s. Jonas may be annoyed by this, but he doesn’t pay a lot of heed to the young man. When he is received by Montague, he finds himself in the presence of the Chairman himself, Mr. Crimple, Dr. Jobling and two other gentlemen, Messrs Pip and Wolf, whose task it seems to be to talk so much of the social circles which will now open themselves to Jonas as to make his head quite dizzy. Apart from that, the wine that is being served, and that Jonas has liberal recourse to, seeing that he does not have to pay for it, adds to the dizziness invading our friend’s brain. During the extremely sumptuous meal – Montague makes a point of stressing that a meal like that is a daily luxury for him, well, not nearly a luxury at all – Jonas is more and more impressed by the lifestyle he witnesses, and since it also becomes clear that he himself will not be expected to go to similar expenses, it being Montague’s duty, and pleasure, to represent the company by standing treat to visitors and customers, so that Jonas himself can salt away all his profits, it is just a matter of time before Jonas is fully entangled in the web laid out by the wily Montague. In the course of the dinner, the wine flows more and more freely, and Jonas is becoming drunker and drunker, more and more displaying the despicable and cur-like aspects of his character, e.g. by openly showing his contempt for Montague’s lavishness in spending while enjoying all the profusion to the utmost. Montague, however, takes no umbrage at this thankless behaviour because, apparently, he knows that eventually he will have the upper hand over Jonas.

When, later in the evening, Crimple asks his friend whether Jonas is hooked, Montague replies that he is, with a very strong iron. By this time, it being around three o’ clock in the morning, Jonas has drunk himself into a sodden stupor, and Montague orders Bailey to take that gentleman home. The young sprite exerts his order as best he can, treating the half-asleep Jonas more like an unwieldy portmanteau than like a person, and when he finally arrives at Jonas’s house and rings the bell, he finds that Merry has been waking up for her husband. However, when he spies through the keyhole and sees her advance towards the door, what he sees is this:

”It was the merry one herself. But sadly, strangely altered! So careworn and dejected, so faltering and full of fear; so fallen, humbled, broken; that to have seen her quiet in her coffin would have been a less surprise.”

Recognizing Bailey, a hint of her old merry self comes to her face, but that is only short-lived – so much so that it brings tears into Bailey’s eyes. He calms her down, or tries so, by saying that her husband is just a little inebriated, and then he helps Jonas into the house, witnessing the attempts on Merry’s part to soothe the grumpy temper of her husband, while Jonas, in his drunkenness – but he would also have done so in his sobriety, so much is clear – hurls various curses and invectives at her, calling he a clog tied to him, who could have risen even higher without her, and a ”mewling, white-faced cat”, which I didn’t find very nice, but rather original. He also shows that he means to pay back her former humiliations of him, when he says,

”’You made me bear your pretty humours once, and ecod I’ll make you bear mine now. I always promised myself I would. I married you that I might. I’ll know who’s master, and who’s slave! […] There’s not a pretty slight you ever put upon me, nor a pretty trick you ever played me, nor a pretty insolence you ever showed me, that I won’t pay back a hundred-fold. […]’”

But Bailey has left by now, because Merry entreated him to do so, and so the boy also fails to witness when Jonas sinks even lower by beating his wife.

QUESTIONS

What do you think of this chapter? I must confess that the first part of it seemed like a rehash of Chapter 27, and that Pip and Wolf with all their talk, tired my patience a bit. They reminded me of Pyke and Pluck in a way, and they clearly were invited by Montague with a view of getting Jonas deeper into the spider’s web.

What do you think of Merry’s change? Is it believable? It’s not too long ago since we last saw her enter her new home, and already she is quite a different woman. Can this happen so quickly?

Do you think Pecksniff knows what kind of life his daughter is led? If he did so, would he intervene?

Despite the violence and scorn Merry experiences from Jonas, she seems bent on propitiating him and on conquering him by kindness. What do you think of this? And, since I think this is the author’s idea(l) of womanhood interfering, what do you think of the close of the chapter, when the narrator says,

”Oh woman, God beloved in old Jerusalem! The best among us need deal lightly with thy faults, if only for the punishment thy nature will endure, in bearing heavy evidence against us, on the Day of Judgment!”?

Chapter 29

This chapter may well be a key chapter for the whole novel, and its main purpose is probably to prepare the reader for some kind of solution to some kind of problem or mystery that is not really specified, and thus it may create suspense or, because of all its vagueness in this point, fail to do so.

The chapter begins on the day following Mr. Bailey’s encounter with the unhappy Merry, and we find the young go-getter on his way to Poll Sweedlepipe in order to pay him a visit. He enters the shop rather boisterously, trying to get as much sound of the bells as possible, and quickly engages in conversation with the meek Poll, their first topic being the incomparable Mrs. Gamp, about whom Young Bailey has the following thing to say, which proves that he can look deeper than most people:

While he is talking in this world-wise way about Mrs. Gamp, the idea occurs to him that he might need a shave, and accordingly he indulges into this luxury, much to the amazement of Mr. Sweedlepipe, who goes through the motions of shaving his friend, although his chin is largely unbesieged by bristle and hair. When Mrs. Gamp arrives – she is on an important mission, being appointed to accompany her fever patient to the countryside and wait there until another nurse is found –, Mr. Bailey addresses her with quite some familiarity, which makes the midwife remark that the young boy is full of ”Bragian boldness”, although she evidently takes pleasure in these banters. Her reaction is further proof to Bailey that Sarah must have formed some unlucky attachment to him.

Mrs. Gamp tells them that her patient is going to be taken to Hertfordshire, his native county, and that she is supposed to look after him until they find a nurse from the area. Mrs. Gamp tells them that she has little hope for her patient because he is haunted by fever and talks and raves every night about the strangest things. When Poll asks her what he raves about, for example ghosts, she remembers her professional ethos and repudiates the question altogether. They also talk about Jonas Chuzzlewit and his wife, and when Mrs. Gamp learns that Merry had been waking up all night for her husband she says that she cannot understand such behaviour. She also says, with regard to Jonas, that he may look like an exemplary man but you never know what is in people’s hearts and minds.

QUESTIONS

What do the conversations and the three persons’ contributions reveal about their characters? For example, when Mrs. Gamp says that Merry should not have waited for her husband, what does it reveal about herself, or about her own marriage? – We are obviously witnessing gossip, but Bailey abstains from telling the others what he saw when he encountered Merry at the door. He could have astonished his listeners and made quite a sensation, but he kept silent. What does this tell about him? And what does Mrs. Gamp’s silence about her patient’s fever dreams tell us about her?

Bailey and Poll are so curious about Mrs. Gamp’s patient that they resolve to accompany her to the hotel where she is to relieve Mrs. Prig of her duty of watching over the man, who is called Lewsome, by the way. When they arrive, we witness Mrs. Gamp and Mrs. Prig’s rough ways with their patients and how they make the feeble convalescent go through some slight ordeal. We also see that the man who pays for Mr. Lewsome’s tendance is none other but John Westlock. Some further mystery is added when Mr. Lewsome says that he is soon going to want to have a word with John about ”something very particular and strange […] that has been a dreadful weight on [his] mind, through this long illness.” John wants to ask the nurses to leave the room, but Lewsome tells him that he is still too weak to tell his secret, although it is very frightful to tell and to think about.

QUESTIONS

There is John Westlock again, and we might still ask ourselves why he is paying people to look after the stranger. The most obvious question, however, is what on earth Mr. Lewsome wants to get off his mind.

It is not so easy to get Mrs. Gamp and all her luggage on the coach, but finally it is done, and the nurse and her patient depart – with the secret still untold. By the way, maybe Mrs. Gamp knows about it? After all, the patient has been speaking in his fever dreams …

When they leave, the Mould family happen to pass by them, and seeing the patient, Mr. Mould already starts calculating and asking himself whether he will not sooner or later see Mr. Lewsome again. We don’t know whether the appearance of the undertaker and his wife will be important later on, but I am sure that the last sentence of this chapter had better be remembered:

All in all, some mysteries are hinted at, but everything remains extraordinarily vague. Let me therefore finish this recap with the question I started it with: Are these attempts at creating suspense successful with you?

This chapter may well be a key chapter for the whole novel, and its main purpose is probably to prepare the reader for some kind of solution to some kind of problem or mystery that is not really specified, and thus it may create suspense or, because of all its vagueness in this point, fail to do so.

The chapter begins on the day following Mr. Bailey’s encounter with the unhappy Merry, and we find the young go-getter on his way to Poll Sweedlepipe in order to pay him a visit. He enters the shop rather boisterously, trying to get as much sound of the bells as possible, and quickly engages in conversation with the meek Poll, their first topic being the incomparable Mrs. Gamp, about whom Young Bailey has the following thing to say, which proves that he can look deeper than most people:

”‘There’s the remains of a fine woman about Sairah, Poll,’ […]”

While he is talking in this world-wise way about Mrs. Gamp, the idea occurs to him that he might need a shave, and accordingly he indulges into this luxury, much to the amazement of Mr. Sweedlepipe, who goes through the motions of shaving his friend, although his chin is largely unbesieged by bristle and hair. When Mrs. Gamp arrives – she is on an important mission, being appointed to accompany her fever patient to the countryside and wait there until another nurse is found –, Mr. Bailey addresses her with quite some familiarity, which makes the midwife remark that the young boy is full of ”Bragian boldness”, although she evidently takes pleasure in these banters. Her reaction is further proof to Bailey that Sarah must have formed some unlucky attachment to him.

Mrs. Gamp tells them that her patient is going to be taken to Hertfordshire, his native county, and that she is supposed to look after him until they find a nurse from the area. Mrs. Gamp tells them that she has little hope for her patient because he is haunted by fever and talks and raves every night about the strangest things. When Poll asks her what he raves about, for example ghosts, she remembers her professional ethos and repudiates the question altogether. They also talk about Jonas Chuzzlewit and his wife, and when Mrs. Gamp learns that Merry had been waking up all night for her husband she says that she cannot understand such behaviour. She also says, with regard to Jonas, that he may look like an exemplary man but you never know what is in people’s hearts and minds.

QUESTIONS

What do the conversations and the three persons’ contributions reveal about their characters? For example, when Mrs. Gamp says that Merry should not have waited for her husband, what does it reveal about herself, or about her own marriage? – We are obviously witnessing gossip, but Bailey abstains from telling the others what he saw when he encountered Merry at the door. He could have astonished his listeners and made quite a sensation, but he kept silent. What does this tell about him? And what does Mrs. Gamp’s silence about her patient’s fever dreams tell us about her?

Bailey and Poll are so curious about Mrs. Gamp’s patient that they resolve to accompany her to the hotel where she is to relieve Mrs. Prig of her duty of watching over the man, who is called Lewsome, by the way. When they arrive, we witness Mrs. Gamp and Mrs. Prig’s rough ways with their patients and how they make the feeble convalescent go through some slight ordeal. We also see that the man who pays for Mr. Lewsome’s tendance is none other but John Westlock. Some further mystery is added when Mr. Lewsome says that he is soon going to want to have a word with John about ”something very particular and strange […] that has been a dreadful weight on [his] mind, through this long illness.” John wants to ask the nurses to leave the room, but Lewsome tells him that he is still too weak to tell his secret, although it is very frightful to tell and to think about.

QUESTIONS

There is John Westlock again, and we might still ask ourselves why he is paying people to look after the stranger. The most obvious question, however, is what on earth Mr. Lewsome wants to get off his mind.

It is not so easy to get Mrs. Gamp and all her luggage on the coach, but finally it is done, and the nurse and her patient depart – with the secret still untold. By the way, maybe Mrs. Gamp knows about it? After all, the patient has been speaking in his fever dreams …

When they leave, the Mould family happen to pass by them, and seeing the patient, Mr. Mould already starts calculating and asking himself whether he will not sooner or later see Mr. Lewsome again. We don’t know whether the appearance of the undertaker and his wife will be important later on, but I am sure that the last sentence of this chapter had better be remembered:

”When the light cloud of bustle hanging round the coach was thus dispersed, Nadgett was seen in the darkest box of the Bull coffee–room, looking wistfully up at the clock — as if the man who never appeared were a little behind his time.”

All in all, some mysteries are hinted at, but everything remains extraordinarily vague. Let me therefore finish this recap with the question I started it with: Are these attempts at creating suspense successful with you?

Tristram wrote: "“unwieldly as summer flies but newly rescued from a honey–pot.” Flies which land in a honey-pot may have a good time of it, but will ultimately die – is this some kind of foreshadowing?..."

Tristram wrote: "“unwieldly as summer flies but newly rescued from a honey–pot.” Flies which land in a honey-pot may have a good time of it, but will ultimately die – is this some kind of foreshadowing?..."Yes, but the flies are rescued--meaning Tigg gets the gluttony without the punishment?

Tristram wrote: "He also shows that he means to pay back her former humiliations of him, when he says,

Tristram wrote: "He also shows that he means to pay back her former humiliations of him, when he says,”’You made me bear your pretty humours once, and ecod I’ll make you bear mine now. I always promised myself I would. I married you that I might. I’ll know who’s master, and who’s slave! […] There’s not a pretty slight you ever put upon me, nor a pretty trick you ever played me, nor a pretty insolence you ever showed me, that I won’t pay back a hundred-fold. […]’”

But Bailey has left by now, because Merry entreated him to do so, and so the boy also fails to witness when Jonas sinks even lower by beating his wife..."

I was very puzzled in the last installment as to what exactly Merry was supposed to be warning us about, but my guess is now that her sin was merely thinking she had some power in a situation when she didn't. Before her marriage, she was vain: she liked being courted and especially being courted above her sister; she liked to keep the men dangling after her, and she seems to think this will be the ongoing situation with Jonas if she marries him and she can continue keeping him dangling and miserable for her sake, and she is drastically wrong.

I still don't get, though, why she would marry him when she hated him so much that she was happy Tom knocked him. Wanting Jonas to suffer pain at another person's hand is different from wanting him to suffer it at her own. So I still don't altogether find her a coherent character.

Tristram wrote: "Despite the violence and scorn Merry experiences from Jonas, she seems bent on propitiating him and on conquering him by kindness. What do you think of this? And, since I think this is the author’s idea(l) of womanhood interfering..."

Tristram wrote: "Despite the violence and scorn Merry experiences from Jonas, she seems bent on propitiating him and on conquering him by kindness. What do you think of this? And, since I think this is the author’s idea(l) of womanhood interfering..."I guess we can chalk it up to Dickens's imaginative powers that he must have come into contact with many attractive young gentlewomen in the course of his life, and yet not one actual human being appears to have broken through the fog of the Ideal Woman in his head.

At least not yet, at this stage of his career.

Chapter 27

Chapter 27Does anyone besides me see parallels between Bailey and Mark? They are both free spirited young men who go out into the world to conquer it.

One of the plot lines came into clear focus when Jonas walked into Tiggs' lair . . . Whoops! . . . I mean board room.

Tiggs could sell property in Eden without ever leaving London. Another parallel, perhaps? -- con men in both countries.

Jonas was seeking an insurance policy for his wife in case he tired of her. But Jonas, always the predator, may have grabbed the tail of a bigger predator.

Does Joblings know what is going on? Did he bring Jonas there because he likes him? Or because he doesn't like him?

I think Jobling very much knows what's going on. He just wants the extra person falling for their scheme I think, because he gains money by it. And isn't it glorious, to dupe the one person you know to be proud of his miserly and sharp on money ways? Like the cherry on top on one side, and the way Jonas conducts himself probably easy prey on the other, because he is so full of himself and wants to prove he is as good with money as his father was.

Hm, I didn't realize the parallels between Mark and Bailey, I'll watch closer for the similarities from now on.

Perhaps Tiggs is somehow rescued, by pushing others over into the honey pot? Perhaps he'll get his portion of horrors anyway later, and it's a forshadowing that he may be lucky now, but he'll fall into a new honey pot sooner or later? I don't know, we'll see.

Knowing Dickens' view on women, could the thing with Merry be that if she had behaved more like she 'should have' (in Dickens' perspective), she wouldn't have been in a marriage like this? That if her dad, sister and her hadn't been such hypocrites, she could have had an ally in her sister, and her dad wouldn't have let her fall into this pit? I get a huge 'sins of the father brought upon the next generation' vibe in this book anyway. But it are all speculations for me too at this point.

Oh and I could have done without Wolf and Pip too in these chapters. Although Pip did remind me of Great expectations, at least with his name.

The whole Anglo-Bengalee firm thing is a bit mlm-like: selling the dream, live the life you want others to believe you can live when they look, so that they fall into the pit of joining and start making you money.

Hm, I didn't realize the parallels between Mark and Bailey, I'll watch closer for the similarities from now on.

Perhaps Tiggs is somehow rescued, by pushing others over into the honey pot? Perhaps he'll get his portion of horrors anyway later, and it's a forshadowing that he may be lucky now, but he'll fall into a new honey pot sooner or later? I don't know, we'll see.

Knowing Dickens' view on women, could the thing with Merry be that if she had behaved more like she 'should have' (in Dickens' perspective), she wouldn't have been in a marriage like this? That if her dad, sister and her hadn't been such hypocrites, she could have had an ally in her sister, and her dad wouldn't have let her fall into this pit? I get a huge 'sins of the father brought upon the next generation' vibe in this book anyway. But it are all speculations for me too at this point.

Oh and I could have done without Wolf and Pip too in these chapters. Although Pip did remind me of Great expectations, at least with his name.

The whole Anglo-Bengalee firm thing is a bit mlm-like: selling the dream, live the life you want others to believe you can live when they look, so that they fall into the pit of joining and start making you money.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "He also shows that he means to pay back her former humiliations of him, when he says,

”’You made me bear your pretty humours once, and ecod I’ll make you bear mine now. I always p..."

Hi Julie

Yes. I too am puzzled with Merry and her actions. I can understand her wanting to better her sister and take a seemingly good catch. I can see her playfully teasing Jonas as a way to keep and hold his attention. That said, her language goes beyond the merely playful and into the category of painful. She will have her hands full with Jonas because he plays a much more mean and aggressive game. I also think that Jonas will bear a grudge for a very long time, and any grudge will fester in his mind.

”’You made me bear your pretty humours once, and ecod I’ll make you bear mine now. I always p..."

Hi Julie

Yes. I too am puzzled with Merry and her actions. I can understand her wanting to better her sister and take a seemingly good catch. I can see her playfully teasing Jonas as a way to keep and hold his attention. That said, her language goes beyond the merely playful and into the category of painful. She will have her hands full with Jonas because he plays a much more mean and aggressive game. I also think that Jonas will bear a grudge for a very long time, and any grudge will fester in his mind.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 27

Does anyone besides me see parallels between Bailey and Mark? They are both free spirited young men who go out into the world to conquer it.

One of the plot lines came into clear focus..."

Hi Xan

Yes. As we move further into the novel the parallels and contrasts of characters becomes more apparent. And as you mentioned, Dickens is now working with characters and plot lines in two different countries.

I especially liked your insight and comment about Tigg’s being able to sell land in Eden. There are all types of people and they can be found equally in all places.

For me, at least, the novel is starting to make more sense and have more structure now I faintly see what Dickens may be up to in his plot.

Does anyone besides me see parallels between Bailey and Mark? They are both free spirited young men who go out into the world to conquer it.

One of the plot lines came into clear focus..."

Hi Xan

Yes. As we move further into the novel the parallels and contrasts of characters becomes more apparent. And as you mentioned, Dickens is now working with characters and plot lines in two different countries.

I especially liked your insight and comment about Tigg’s being able to sell land in Eden. There are all types of people and they can be found equally in all places.

For me, at least, the novel is starting to make more sense and have more structure now I faintly see what Dickens may be up to in his plot.

Tristram

I believe we are getting into a more interesting phase of the novel. Some excellent mysteries are introduced, the relationship between Merry and Jonas is clear evidence that Jonas is a nasty piece of business and we have just witnessed the rapid decline of Merry. I do not take pleasure in what has happened to her, but her decline is clear evidence of how evil Jonas is.

While Jonas may be cruel and nasty he is no match for Tigg. He is a serpent. The Anglo-Bengalee society is a refined version of the Eden land scheme in America. It is interesting that Dickens would offer two con games for our pleasure, especially one based in England and one in America. Was Dickens trying to balance the plot so he would not offend either countries sensibilities? Is it just chance that the American Eden is inhabited by defeated people and snakes while we have Tigg in England being called Satanic. Clearly, we will have individuals fall prey to Tigg’s scheme.

Nadgett is a mystery. When the reader meets Tigg for the second time he has transformed himself into someone else. Will we meet Nadgett again? What will he be upon our next encounter?

And speaking about characters popping up again we have Bailey. Once a resident of Todgers’s and now a servant of Tigg’s, Bailey links the two locations and their residents together into a loose web. Merry, who was Merry at Todgers’s is now miserable. More than one characters personality of role in the novel has been altered by Dickens. I think the plot is heating up.

I believe we are getting into a more interesting phase of the novel. Some excellent mysteries are introduced, the relationship between Merry and Jonas is clear evidence that Jonas is a nasty piece of business and we have just witnessed the rapid decline of Merry. I do not take pleasure in what has happened to her, but her decline is clear evidence of how evil Jonas is.

While Jonas may be cruel and nasty he is no match for Tigg. He is a serpent. The Anglo-Bengalee society is a refined version of the Eden land scheme in America. It is interesting that Dickens would offer two con games for our pleasure, especially one based in England and one in America. Was Dickens trying to balance the plot so he would not offend either countries sensibilities? Is it just chance that the American Eden is inhabited by defeated people and snakes while we have Tigg in England being called Satanic. Clearly, we will have individuals fall prey to Tigg’s scheme.

Nadgett is a mystery. When the reader meets Tigg for the second time he has transformed himself into someone else. Will we meet Nadgett again? What will he be upon our next encounter?

And speaking about characters popping up again we have Bailey. Once a resident of Todgers’s and now a servant of Tigg’s, Bailey links the two locations and their residents together into a loose web. Merry, who was Merry at Todgers’s is now miserable. More than one characters personality of role in the novel has been altered by Dickens. I think the plot is heating up.

Peter wrote: "Was Dickens trying to balance the plot so he would not offend either countries sensibilities? Is it just chance that the American Eden is inhabited by defeated people and snakes while we have Tigg in England being called Satanic. Clearly, we will have individuals fall prey to Tigg’s scheme. ..."

Peter wrote: "Was Dickens trying to balance the plot so he would not offend either countries sensibilities? Is it just chance that the American Eden is inhabited by defeated people and snakes while we have Tigg in England being called Satanic. Clearly, we will have individuals fall prey to Tigg’s scheme. ..."Peter,

I love how you phrased this. I was wondering if Dickens is trying to balance/compensate the satire of the novel as well. We haven't heard from Martin and Mark since chapter 23! That seems a very long time to leave those characters alone (although, I suppose, they're probably not too active in the swamp, anyways).

Tristram, I'm really intrigued by the parallel you've drawn between Eden and the insurance scam. They certainly seem like birds of a feather. I highlighted this quote from Tigg while I was reading:

"'I can tell you,' said Tigg in his ear, 'how many of 'em will buy annuities, effect insurances, bring us their money in a hundred shapes and ways, force it upon us, trust us as if we were the Mint; yet know no more about us than you do of that crossing-sweeper at the corner. Not so much! Ha, ha!'

Martin, much like Tigg's victims, put his complete trust in the wrong people.

Chapter 28

Chapter 28I think Bailey will toss Jonas our a third story window before all is said and done.

Was Merry ever really bad? I'm going to have to look. I mean she's a reader, and a reader is never bad right? Well, maybe a grump once in a while, but never more than that.

Even if she was bad, she doesn't deserve this wretch.

Tristram wrote: "Do you think Pecksniff knows what kind of life his daughter is led? If he did so, would he intervene?"

Tristram wrote: "Do you think Pecksniff knows what kind of life his daughter is led? If he did so, would he intervene?"No. He had a real good idea how Jonas would treat Merry by the way he treated him.

Emma wrote: "Peter wrote: "Was Dickens trying to balance the plot so he would not offend either countries sensibilities? Is it just chance that the American Eden is inhabited by defeated people and snakes while..."

Hi Emma

Yes, I do think Dickens is trying, at least to an extent, to balance his handling of America and England. Dickens seems to be portioning his satire out as well. I can’t shake the feeling that the novel’s focus and criticism of America comes as a result of his observations of America during his first visit. I feel a rawness to his words, his observations, his language that seems absent in his English scenes.

Hi Emma

Yes, I do think Dickens is trying, at least to an extent, to balance his handling of America and England. Dickens seems to be portioning his satire out as well. I can’t shake the feeling that the novel’s focus and criticism of America comes as a result of his observations of America during his first visit. I feel a rawness to his words, his observations, his language that seems absent in his English scenes.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 28

I think Bailey will toss Jonas our a third story window before all is said and done.

Was Merry ever really bad? I'm going to have to look. I mean she's a reader, and a reader is never ..."

Hello Xan

Merry was young and innocent. She has a spirit to her, but I agree she did not deserve to end up with Jonas. You are right. She was the reader of the Pecksniff family and who can dislike a reader, even a grumpy one?

I think Bailey will toss Jonas our a third story window before all is said and done.

Was Merry ever really bad? I'm going to have to look. I mean she's a reader, and a reader is never ..."

Hello Xan

Merry was young and innocent. She has a spirit to her, but I agree she did not deserve to end up with Jonas. You are right. She was the reader of the Pecksniff family and who can dislike a reader, even a grumpy one?

Chapter 29

Chapter 29"There's the remains of a fine woman about Sairah, Poll," observed Mr. Bailey, with genteel difference.

Hahahahahahahahahahah

And Bailey's shave is a scream.

There are some really funny passages in this novel. Mrs Gamp settling in to watch over her new patient is another one of them.

There is some suspense, but since Lewsome mentions Jonas in his ravings, the suspense isn't that much.

I think Bailey has a weakness for Merry. Thus the shave.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "“unwieldly as summer flies but newly rescued from a honey–pot.” Flies which land in a honey-pot may have a good time of it, but will ultimately die – is this some kind of foreshado..."

We'll have to wait and see. Considering that Tigg is plotting the ruin of hundreds of families on a large scale, I'd say that I wouldn't like him to get off the hook so easily.

We'll have to wait and see. Considering that Tigg is plotting the ruin of hundreds of families on a large scale, I'd say that I wouldn't like him to get off the hook so easily.

Julie wrote: "I still don't get, though, why she would marry him when she hated him so much that she was happy Tom knocked him. Wanting Jonas to suffer pain at another person's hand is different from wanting him to suffer it at her own. So I still don't altogether find her a coherent character."

I think that Merry's worst faults are basically the ones you named: There is a lot of vanity in her, but mostly of the kind that comes from being pampered by an irresponsible parent, and of having it her own way most of the time. She is also giddy-headed, and likes being courted and flattered - but I couldn't be very hard on her for that, taking into account that she comes from the countryside, where she hast probably spent all her life, and now finds herself in London, in a boarding house full of young gentlemen. Merry, in short, is what you could call a spoilt brat. Even if she looked down on and was mean to Tom Pinch, I liked her more than her sister, who is really mean-spirited and shows the same signs of hypocrisy and miserliness as her father.

She does not really deserve an ogre like Jonas, does she now? As to her being delighted to see Tom hurt Jonas, I think it was Charity who showed her glee to Tom and promised him to be his friend from now on.

I think that Merry's worst faults are basically the ones you named: There is a lot of vanity in her, but mostly of the kind that comes from being pampered by an irresponsible parent, and of having it her own way most of the time. She is also giddy-headed, and likes being courted and flattered - but I couldn't be very hard on her for that, taking into account that she comes from the countryside, where she hast probably spent all her life, and now finds herself in London, in a boarding house full of young gentlemen. Merry, in short, is what you could call a spoilt brat. Even if she looked down on and was mean to Tom Pinch, I liked her more than her sister, who is really mean-spirited and shows the same signs of hypocrisy and miserliness as her father.

She does not really deserve an ogre like Jonas, does she now? As to her being delighted to see Tom hurt Jonas, I think it was Charity who showed her glee to Tom and promised him to be his friend from now on.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Does Joblings know what is going on? Did he bring Jonas there because he likes him? Or because he doesn't like him?"

I am on the fence as to this question: On the one hand, it is quite clear that Dr. Jobling knows very well about the fraudulent intentions behind the Anglo-Bengalee, although he may not be acquainted with the exact strategy, neither with the point of time when the bomb may explode. On the other hand, I have always thought that he holds Jonas in some regard because of the way he spent money on the occasion of his father's funeral. In the doctor's eyes, Jonas may be a paragon of decency, if not exactly virtue.

I am on the fence as to this question: On the one hand, it is quite clear that Dr. Jobling knows very well about the fraudulent intentions behind the Anglo-Bengalee, although he may not be acquainted with the exact strategy, neither with the point of time when the bomb may explode. On the other hand, I have always thought that he holds Jonas in some regard because of the way he spent money on the occasion of his father's funeral. In the doctor's eyes, Jonas may be a paragon of decency, if not exactly virtue.

Tristram, it was indeed Charity who showed glee about that. And I agree, of the Pecksniff, Merry seemed to be the least bad, and only because she didn't know better. She was stubborn too, but again, she didn't know better. She had up to Martin Sr. talking to her, always been applauded for being stubborn and giddy.

Peter wrote: "Emma wrote: "Peter wrote: "Was Dickens trying to balance the plot so he would not offend either countries sensibilities? Is it just chance that the American Eden is inhabited by defeated people and..."

Yes, Peter, there is definitely a bitter and harsh quality to the satire in the American chapters, which is different from Dickens's usual way of using irony and sarcasm. Remember the Circumlocution Office, remember the Lord Chancellor and the slowly-grinding mills of justice, remember Mr. Bumble and the Poor Law - all these Dickens shot his scathing arrows-of-fire against but the criticism he voiced was always harnessed to the story and, like a good horse, pulled the waggon along.

In the American chapters, however, I have the feeling that Dickens's actual plot is rather thin - although not unimportant -, but that the author uses the American setting to parade a string of characters before us in order to use them as types and representations of things, customs or attitudes he disliked when he was in America. Most of these characters fulfil no other function but that of illustrating Dickens's criticism, and when he has done criticising, for the nonce, they disappear, and the novel would just have been as well without them. This makes the American chapters almost like a novel of ideas, but like one written by a beginner in that discipline. Apart from that, there are some things, like greedy eaters, chewers of tobacco, negligence in personal hygiene, that Dickens mentions over and over again. - Like Mark and Martin, I wish they were back in England by now, because the English parts of the novel are better written and have more interesting characters.

Yes, Peter, there is definitely a bitter and harsh quality to the satire in the American chapters, which is different from Dickens's usual way of using irony and sarcasm. Remember the Circumlocution Office, remember the Lord Chancellor and the slowly-grinding mills of justice, remember Mr. Bumble and the Poor Law - all these Dickens shot his scathing arrows-of-fire against but the criticism he voiced was always harnessed to the story and, like a good horse, pulled the waggon along.

In the American chapters, however, I have the feeling that Dickens's actual plot is rather thin - although not unimportant -, but that the author uses the American setting to parade a string of characters before us in order to use them as types and representations of things, customs or attitudes he disliked when he was in America. Most of these characters fulfil no other function but that of illustrating Dickens's criticism, and when he has done criticising, for the nonce, they disappear, and the novel would just have been as well without them. This makes the American chapters almost like a novel of ideas, but like one written by a beginner in that discipline. Apart from that, there are some things, like greedy eaters, chewers of tobacco, negligence in personal hygiene, that Dickens mentions over and over again. - Like Mark and Martin, I wish they were back in England by now, because the English parts of the novel are better written and have more interesting characters.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Do you think Pecksniff knows what kind of life his daughter is led? If he did so, would he intervene?"

No. He had a real good idea how Jonas would treat Merry by the way he treate..."

Shame on Pecksniff all the more then! To think he would sacrifice his own daughter for money.

No. He had a real good idea how Jonas would treat Merry by the way he treate..."

Shame on Pecksniff all the more then! To think he would sacrifice his own daughter for money.

Tristram wrote: "As to her being delighted to see Tom hurt Jonas, I think it was Charity who showed her glee to Tom and promised him to be his friend from now on..."

Tristram wrote: "As to her being delighted to see Tom hurt Jonas, I think it was Charity who showed her glee to Tom and promised him to be his friend from now on..."Oh, thanks--you're right. I got them mixed up. That makes so much more sense. Of course Charity hates Jonas, having been led on and spurned.

Julie wrote: "Oh, thanks--you're right. I got them mixed up. "

Julie wrote: "Oh, thanks--you're right. I got them mixed up. "So do I. Just the other day some guy was knocking on the door asking for charity, and I gave him no mercy. Had to apologize for the mixup.

I think that one is worth 5 grumps.

The Board

Chapter 27

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

And how are you, Mr. Montague, eh?" said the Medical Officer, throwing himself luxuriously into an easy-chair (they were all easy-chairs in the board-room), and taking a handsome gold snuff-box from the pocket of his black satin waistcoat. "How are you? A little worn with business, eh? If so, rest. A little feverish from wine, humph? If so, water. Nothing at all the matter, and quite comfortable? Then take some lunch. A very wholesome thing at this time of day to strengthen the gastric juices with lunch, Mr Montague."

The Medical Officer (he was the same medical officer who had followed poor old Anthony Chuzzlewit to the grave, and who had attended Mrs Gamp's patient at the Bull) smiled in saying these words; and casually added, as he brushed some grains of snuff from his shirt-frill, "I always take it myself about this time of day, do you know!"

"Bullamy!" said the Chairman, ringing the little bell.

"Sir!"

"Lunch." . . . .

"By your leave there!" cried Bullamy, without. "By your leave! Refreshment for the Board-room!"

"Ha!" said the doctor, jocularly, as he rubbed his hands, and drew his chair nearer to the table. "The true Life Assurance, Mr Montague. The best Policy in the world, my dear sir. We should be provident, and eat and drink whenever we can. Eh, Mr. Crimple?"

The resident Director acquiesced rather sulkily, as if the gratification of replenishing his stomach had been impaired by the unsettlement of his preconceived opinions in reference to its situation. But the appearance of the porter and under-porter with a tray covered with a snow-white cloth, which, being thrown back, displayed a pair of cold roast fowls, flanked by some potted meats and a cool salad, quickly restored his good humour. It was enhanced still further by the arrival of a bottle of excellent madeira, and another of champagne; and he soon attacked the repast with an appetite scarcely inferior to that of the medical officer. ["The Board," Chapter XXVII, "Showing that Old Friends may not only appear with New Faces, but in False Colours: that People are prone to Bite: and that Biters may sometimes be Bitten," facing plate in the 1897 edition; descriptive headline in the 1867 edition: "The Board and its Chairman"]

Commentary: Milking the System:

The doctor has already drawn his chair up to the table in preparation for lunch as he touches the leg of the resident Director, Mr. Crimple (right) — which he had done earlier to make a point about the necessity of Crimple's replenishing the "animal oil" in his body. Bullamy, the officious porter, holds the tray covered with a linen cloth, while the under porter delivers a decanter of madeira (rather than a "bottle") and bottle, still corked, of champagne. The "profusion of rich glass, plate, and china" is not yet evident, and Bullamy has yet to draw back the "snow-white cloth" to reveal a handsome repast.

Phiz has employed the simple visual strategy that he has used on a number of occasions to reveal Pecksniff's character: to demonstrate Tigg's vanity and egocentricity he has positioned a life-sized portrait of the life-assurance director immediately above his head. The effect is to remind the reader of Tigg Montague/Montague Tigg's double identity as cadger and confidence man, a former soldier who abandoned his post under fire and who has been Chevy Slyme's hanger-on before his reincarnation as the Chief Executive Officer of he Anglo-Bengalee Life Assurance Company.

The arrival of Bullamy and the under porter occurs well after the company physician's discussion of board-member and secretary Mr. David Crimple's leg ("The doctor let Mr. Crimple's leg fall suddenly"), and the resident director has "acquiesced rather sulkily" at Dr. Jobling's recommending frequent eating and drinking as "The best Policy in the world," an obvious pun on "insurance policy." Since Dickens only describes Jobling in some detail after the arrival of lunch depicted, Phiz must have felt it necessary to use the plate as a visual introduction to the firm's Medical Officer: "a portentously sagacious chin, . . . his gold watch-chain of the heaviest, and his seals of the largest" (1897 edition, Vol. 2). However, the illustration shows him engaged in conversation with Mr. Montague, several pages earlier, so that the picture is an amalgam of moments illustrated, and introduces as a feature of the "ornamental department" superintended by Tigg himself as the window-dressing of the Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company's board-room, which Phiz has furnished exactly as instructed, with a luxurious Turkey carpet, an impressive portrait of the director, and comfortable easy-chairs.

Several pages in advance of the luncheon scene which Phiz has chosen for the illustration, Dickens mentions the oil portrait as the dominating feature of the board-room: "a Turkey carpet in it, a sideboard, a portrait of Tigg Montague, Esquire, as chairman; a very imposing chair of office" (Phiz shows Tigg's as having a much higher back than the other two armchairs, making it a virtual throne). However, the composition does not permit Phiz sufficient scope for "a long-table, set out at intervals with sheets of blotting-paper, foolscap, clean pens, and ink-stands" (Vol. 2, 1897 edition), with the result that the table is cluttered, and therefore affords no room for the tray that Bullamy is about to deposit.

Descriptive Headline in the Gadshill edition: "The Labourer Worthy of His Hire":

And in the same house remain, eating and drinking such things as they give:

for the labourer is worthy of his hire. Go not from house to house.

— "The Gospel according to St. Luke," 10:7

in The King James Bible.

The languid pose of the Director and the corpulent complacency of the firm's doctor compel the reader to disagree with the biblical aphorism that the "Labourer is worthy of his hire," or rather disagree with the notion that these indolent, fashionably dressed, middle-aged bourgeoisie are "labourers" in the first place. Dickens's deployment of the allusion as a running head is particularly pertinent to the substantial luncheon that the three corporate directors enjoy at the shareholders' expense. Later illustrators likewise depict Tigg as enjoying the best of everything that others' money can buy.

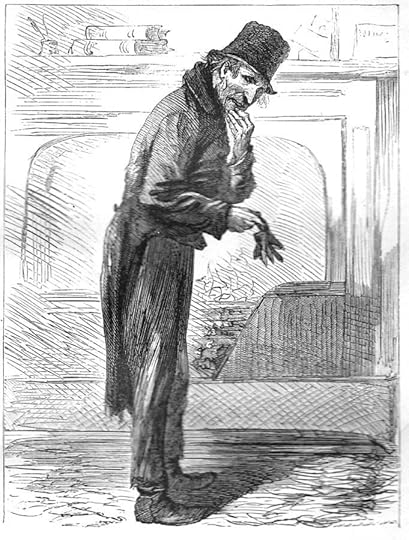

Mr. Nadgett

Chapter 27

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

Shabby, secretive, and reflective, Nadgett is one of Dickens's first detectives. The illustration is presumably set in the lavish boardroom of Chairman Tigg Montague's Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company in London. The plausible confidence man employs Nadgett as his private investigator; in this instance, Tigg charges Nadgett with discovering as much as possible about his hot-headed investor Jonas Chuzzlewit, who has just left. The passage that Eytinge has realised describes Nadgett's appearance, mannerisms, secretive nature:

He was the man at a pound a week who made the inquiries. It was no virtue or merit in Nadgett that he transacted all his Anglo-Bengalee business secretly and in the closest confidence; for he was born to be a secret. He was a short, dried-up, withered old man, who seemed to have secreted his very blood; for nobody would have given him credit for the possession of six ounces of it in his whole body. How he lived was a secret; where he lived was a secret; and even what he was, was a secret. In his musty old pocket-book he carried contradictory cards, in some of which he called himself a coal-merchant, in others a wine-merchant, in others a commission-agent, in others a collector, in others an accountant: as if he really didn't know the secret himself. He was always keeping appointments in the City, and the other man never seemed to come. He would sit on 'Change for hours, looking at everybody who walked in and out, and would do the like at Garraway's, and in other business coffee-houses, in some of which he would be occasionally seen drying a very damp pocket-handkerchief before the fire, and still looking over his shoulder for the man who never appeared. He was mildewed, threadbare, shabby; always had flue upon his legs and back; and kept his linen so secretly buttoning up and wrapping over, that he might have had none — perhaps he hadn't. He carried one stained beaver glove, which he dangled before him by the forefinger as he walked or sat; but even its fellow was a secret. Some people said he had been a bankrupt, others that he had gone an infant into an ancient Chancery suit which was still depending, but it was all a secret. He carried bits of sealing-wax and a hieroglyphical old copper seal in his pocket, and often secretly indited letters in corner boxes of the trysting-places before mentioned; but they never appeared to go to anybody, for he would put them into a secret place in his coat, and deliver them to himself weeks afterwards, very much to his own surprise, quite yellow. He was that sort of man that if he had died worth a million of money, or had died worth twopence halfpenny, everybody would have been perfectly satisfied, and would have said it was just as they expected. And yet he belonged to a class; a race peculiar to the City; who are secrets as profound to one another, as they are to the rest of mankind. [Chapter 27; The Diamond Edition]

Phiz managed to make the private detective Nadgett a shadowy figure, depicting him just once and somewhat indistinctly in "Mr. Nadgett Breathes, as Usual, an Atmosphere of Mystery" (February 1844). Eytinge takes a very different approach, offering the single glove which Nagett is so wont to contemplate, and positioning him in front of an expansive fireplace in the corporate boardroom (account books and an inkstand suggestive of commerce sit on the mantel, left) to accentuate his dinginess. Eytinge's "shabby" figure is indeed "old" and "withered" and even "dried-up," but hardly "short." One has no sense of whether he is wearing a shirt or not. A great observer of mankind and supremely suspicious of those whom he is hired to investigate, Eytinge's Nadgett, his hand to his chin, seems to turn his thoughtful gaze upon the reader.

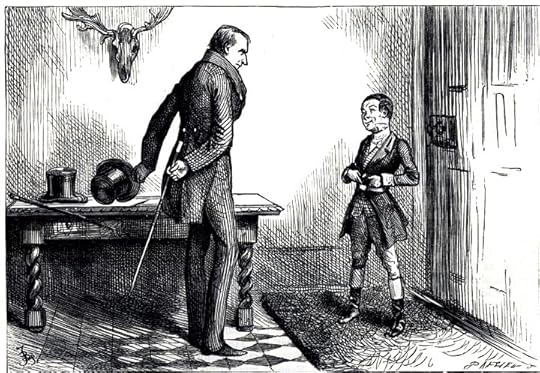

The Spider and the Fly

Chapter 27

Fred Barnard

Respectively Mr. Tigg Montague, swindling insurance magnate, right, and Jonas Chuzzlewit, gullible shareholder in the Anglo-Bengalee: given Jonas's volatile and vindictive nature, one may rightly wonder who is the spider and who the fly since both are caught up in Montague Tigg's web of deceit.

Text Illustrated:

‘I learn from our friend,’ said Tigg, drawing his chair towards Jonas with a winning ease of manner, ‘that you have been thinking—’

‘Oh! Ecod then he’d no right to say so,’ cried Jonas, interrupting. ‘I didn’t tell him my thoughts. If he took it into his head that I was coming here for such or such a purpose, why, that’s his lookout. I don’t stand committed by that.’

Jonas said this offensively enough; for over and above the habitual distrust of his character, it was in his nature to seek to revenge himself on the fine clothes and the fine furniture, in exact proportion as he had been unable to withstand their influence.

‘If I come here to ask a question or two, and get a document or two to consider of, I don’t bind myself to anything. Let’s understand that, you know,’ said Jonas.

‘My dear fellow!’ cried Tigg, clapping him on the shoulder, ‘I applaud your frankness. If men like you and I speak openly at first, all possible misunderstanding is avoided. Why should I disguise what you know so well, but what the crowd never dream of? We companies are all birds of prey; mere birds of prey. The only question is, whether in serving our own turn, we can serve yours too; whether in double-lining our own nest, we can put a single living into yours. Oh, you’re in our secret. You’re behind the scenes. We’ll make a merit of dealing plainly with you, when we know we can’t help it.’

It was remarked, on the first introduction of Mr Jonas into these pages, that there is a simplicity of cunning no less than a simplicity of innocence, and that in all matters involving a faith in knavery, he was the most credulous of men. If Mr Tigg had preferred any claim to high and honourable dealing, Jonas would have suspected him though he had been a very model of probity; but when he gave utterance to Jonas’s own thoughts of everything and everybody, Jonas began to feel that he was a pleasant fellow, and one to be talked to freely.

He changed his position in the chair, not for a less awkward, but for a more boastful attitude; and smiling in his miserable conceit rejoined:

‘You an’t a bad man of business, Mr Montague. You know how to set about it, I will say.’

‘Tut, tut,’ said Tigg, nodding confidentially, and showing his white teeth; ‘we are not children, Mr Chuzzlewit; we are grown men, I hope.’

Jonas assented, and said after a short silence, first spreading out his legs, and sticking one arm akimbo to show how perfectly at home he was,

‘The truth is—’

‘Don’t say, the truth,’ interposed Tigg, with another grin. ‘It’s so like humbug.’

Greatly charmed by this, Jonas began again.

‘The long and the short of it is—’

‘Better,’ muttered Tigg. ‘Much better!’

‘—That I didn’t consider myself very well used by one or two of the old companies in some negotiations I have had with ‘em—once had, I mean. They started objections they had no right to start, and put questions they had no right to put, and carried things much too high for my taste.’

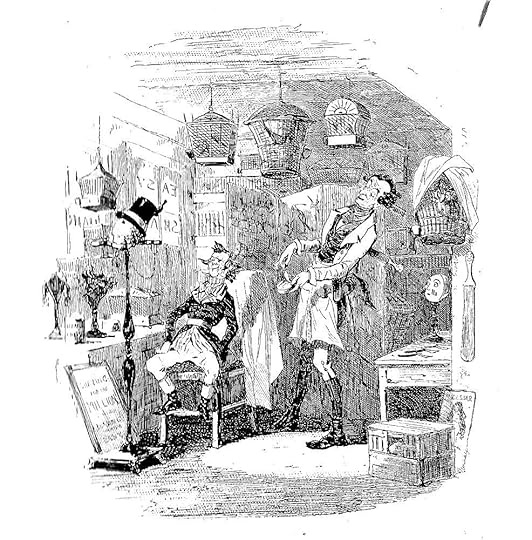

"Mr. Montague," said Jobling, "Allow me, my friend Mr. Chuzzlewit."

Chapter 27

Charles Edmund Brock

Text Illustrated:

‘Talking of wine,’ said the doctor, ‘reminds me of one of the finest glasses of light old port I ever drank in my life; and that was at a funeral. You have not seen anything of—of that party, Mr Montague, have you?’ handing him a card.

‘He is not buried, I hope?’ said Tigg, as he took it. ‘The honour of his company is not requested if he is.’

‘Ha, ha!’ laughed the doctor. ‘No; not quite. He was honourably connected with that very occasion though.’

‘Oh!’ said Tigg, smoothing his moustache, as he cast his eyes upon the name. ‘I recollect. No. He has not been here.’

The words were on his lips, when Bullamy entered, and presented a card to the Medical Officer.

‘Talk of the what’s his name—’ observed the doctor rising.

‘And he’s sure to appear, eh?’ said Tigg.

‘Why, no, Mr Montague, no,’ returned the doctor. ‘We will not say that in the present case, for this gentleman is very far from it.’

‘So much the better,’ retorted Tigg. ‘So much the more adaptable to the Anglo-Bengalee. Bullamy, clear the table and take the things out by the other door. Mr Crimple, business.’

‘Shall I introduce him?’ asked Jobling.

‘I shall be eternally delighted,’ answered Tigg, kissing his hand and smiling sweetly.

The doctor disappeared into the outer office, and immediately returned with Jonas Chuzzlewit.

‘Mr Montague,’ said Jobling. ‘Allow me. My friend Mr Chuzzlewit. My dear friend—our chairman. Now do you know,’ he added checking himself with infinite policy, and looking round with a smile; ‘that’s a very singular instance of the force of example. It really is a very remarkable instance of the force of example. I say our chairman. Why do I say our chairman? Because he is not my chairman, you know. I have no connection with the company, farther than giving them, for a certain fee and reward, my poor opinion as a medical man, precisely as I may give it any day to Jack Noakes or Tom Styles. Then why do I say our chairman? Simply because I hear the phrase constantly repeated about me. Such is the involuntary operation of the mental faculty in the imitative biped man. Mr Crimple, I believe you never take snuff? Injudicious. You should.’

"Times is changed, ain't they?

Chapter 28

Fred Barnard

Here Jonas Chuzzlewit encounters Bailey Junior, now a liveried servant at Tigg Montague's establishment and risen far above the tawdry world of Mrs. Todger's rooming house.

Text Illustrated:

But he determined to proceed with cunning and caution, and to be very keen on his observation of the gentility of Mr Montague’s private establishment. For it no more occurred to this shallow knave that Montague wanted him to be so, or he wouldn’t have invited him while his decision was yet in abeyance, than the possibility of that genius being able to overreach him in any way, pierced through his self-deceit by the inlet of a needle’s point. He had said, in the outset, that Jonas was too sharp for him; and Jonas, who would have been sharp enough to believe him in nothing else, though he had solemnly sworn it, believed him in that, instantly.

It was with a faltering hand, and yet with an imbecile attempt at a swagger, that he knocked at his new friend’s door in Pall Mall when the appointed hour arrived. Mr Bailey quickly answered to the summons. He was not proud and was kindly disposed to take notice of Jonas; but Jonas had forgotten him.

‘Mr Montague at home?’

‘I should hope he wos at home, and waiting dinner, too,’ said Bailey, with the ease of an old acquaintance. ‘Will you take your hat up along with you, or leave it here?’

Mr Jonas preferred leaving it there.

‘The hold name, I suppose?’ said Bailey, with a grin.

Mr Jonas stared at him in mute indignation.

‘What, don’t you remember hold mother Todgers’s?’ said Mr Bailey, with his favourite action of the knees and boots. ‘Don’t you remember my taking your name up to the young ladies, when you came a-courting there? A reg’lar scaly old shop, warn’t it? Times is changed ain’t they. I say how you’ve growed!’

Without pausing for any acknowledgement of this compliment, he ushered the visitor upstairs, and having announced him, retired with a private wink.

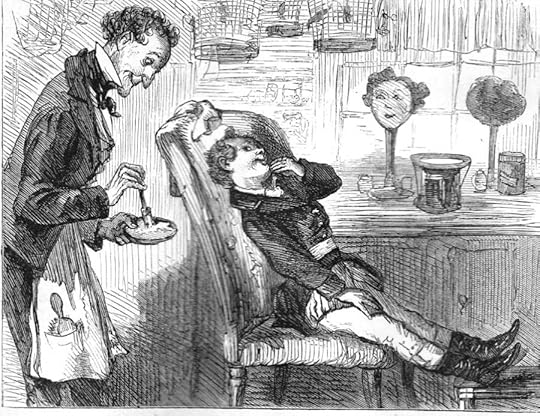

Easy Shaving

Chapter 29

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Poll," he said, "I ain't as neat as I could wish about the gills. Being here, I may as well have a shave, and get trimmed close."

The barber stood aghast; but Mr. Bailey divested himself of his neck-cloth, and sat down in the easy shaving chair with all the dignity and confidence in life. There was no resisting his manner. The evidence of sight and touch became as nothing. His chin was as smooth as a new-laid egg or a scraped Dutch cheese; but Poll Sweedlepipe wouldn't have ventured to deny, on affidavit, that he had the beard of a Jewish rabbi.

"Go with the grain, Poll, all round, please," said Mr. Bailey, screwing up his face for the reception of the lather. "You may do wot you like with the bits of whisker. I don't care for 'em."

The meek little barber stood gazing at him with the brush and soap-dish in his hand, stirring them round and round in a ludicrous uncertainty, as if he were disabled by some fascination from beginning. At last he made a dash at Mr Bailey's cheek. Then he stopped again, as if the ghost of a beard had suddenly receded from his touch; but receiving mild encouragement from Mr. Bailey, in the form of an adjuration to "Go in and win," he lathered him bountifully. Mr. Bailey smiled through the suds in his satisfaction. "Gently over the stones, Poll. Go a tip-toe over the pimples!"

Poll Sweedlepipe obeyed, and scraped the lather off again with particular care. Mr. Bailey squinted at every successive dab, as it was deposited on a cloth on his left shoulder, and seemed, with a microscopic eye, to detect some bristles in it; for he murmured more than once “Reether redder than I could wish, Poll.” The operation being concluded, Poll fell back and stared at him again, while Mr Bailey, wiping his face on the jack-towel, remarked, “that arter late hours nothing freshened up a man so much as a easy shave.” [Chapter XXIX, "In which some People are Precocious, others Professional, others Mysterious; all in their several Ways," 1844 edition; descriptive headline in the 1867 edition: "Easy Shaving"]

Commentary: Bailey Junior Rises in the World:

In "Easy Shaving," the second illustration for the November 1843 instalment, Phiz underscores Tigg's unexpected rise in fortune by providing as a visual analogue the concomitant rise of Master Bailey to the enviable position of the financier Montague's liveried footman. His old friend, the barber-cum-bird fancier Poll Sweedlepipe, is astonished at his old friend's apotheosis. As Michael Steig remarks in Dickens and Phiz,

The themes of metamorphosis and parody are worked out intricately, for in the first etching ["The Board"] Browne parodies the melodramatic pose of "Montague" by a still more pretentious portrait. . . . The parallels in the companion plate amusingly deflate Tigg's pretence: Bailey is being shaved by the genuinely admiring Poll, although his beard — like Tigg's respectability and his capital — is imaginary.

The footman's livery seems too big for Bailey, who is so small that he can barely straddle the barber's easy-shaving chair, the analogue for Montague's throne-like regency chair in the companion piece. And just as Poll studies the effect of his shaving on Bailey's visage, so Bailey seems impressed by the effect of his footman's hat and wig on Poll's coat rack (left), while a wig block (right) and the owl in a cage seem amazed — either at the transformation or at Bailey's effrontery. Steig notes the thematic connection between the two plates for November, 1843:

And as Tigg is being obsequiously waited upon by an associate, butler, servant, and physician, far beyond his intrinsic deserts, so Bailey is being served by the barber, Sweedlepipe, despite the totally imaginary quality of his "beard." This parody is something not brought out directly in the text, and it is a matter of speculation whether the idea to emphasize it in the illustrations was Dickens's or Browne's, since we have no such direct clue as contrasting captions. [Steig, DSA 2, 136]

Dickens takes considerable pains at the opening of chapter 26 to establish the reality of the easy-shaving shop and birds' nest as well as the odd figure of the barbering bird-fancier, a Regency throwback, "a little elderly man" in a velveteen coat, blue stockings, ankle boots, bright-coloured neckerchief, grimy apron, corduroy knee-shorts, and very tall hat. In drawing Poll Phiz, who has substituted leanness for shortness, has in fact given him top-boots to emphasize his height and angularity.

Only later, however, does Master Bailey actually enter the barber's and demand a shave. Browne emphasizes his short stature by his turned-down top-boots, over-sized waistcoat, and white corduroy breeches with a low crotch (all of which, of course, the fashion-conscious Poll pronounces "Beau-ti-ful!" in Chapter 26). In Chapter 26, Bailey bumps into the barber at the corner of Holborn and Kingsgate, agreeing to bear Poll company to Jonas Chuzzlewit's. Finally in Chapter 29 we see together in a single scene Mr. Bailey clad as a footman and the interior of the bird-fancier's shop. The plate accurately includes details from the descriptions in both chapters 26 and 29: the favourite owl, the strop, the razors laid out in a row (right), and Bailey's smooth chin. Phiz, however, invented many of the details, including a can of bear's grease (at the left) and the wig stand surmounted by Bailey's imposing hat plus the large promotional sign "Shaving for the Million," which perhaps alludes obliquely to the Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company and its promise to unwary investors of profits and which complements the advertisement for that useful Eastern commodity, Macassar oil (at right).

Phiz also poses Bailey's head here to match that of "Tigg Montague" in the portrait featured in the companion plate. Family portraits like high-crowned hats were marks of respectability, but in these plates signify the duplicity behind each stately image. Here, Bailey apes his master as his master there apes a gentleman. The exotic oriental screen behind Poll further connects the bird-fancier's and financier's worlds in that the latter, too, has an Eastern furnishing, "a Turkey carpet," which serves as a tangible assurance of the firm's "property in Bengal" (chapter 27).

The precise comic moment that the plate realizes occurs when Master Bailey attempts to enforce Poll's belief in his non-existent whiskers, which are as illusionary as the funds supporting the Anglo-Bengalee Life Assurance Company. The situation in the bird-fancier's shop therefore parallels the scenes in the Anglo-Bengalee boardroom. Like Pecksniff and Jonas, who place credence in Tigg's company owing to its respectable and confident facade, Poll against his better judgment as an experienced barber finds himself caught up in Bailey's illusion. Poll momentarily credits Bailey's self-confident imposture, ready to swear in a legal document that Bailey possesses "the beard of a Jewish rabbi" (Chapter 29). However, the reader wonders whether, unlike Mr. Montague, Mr. Bailey is merely deluding himself. Perhaps Dickens and Phiz are implying that the artful Tigg, who once abandoned his troops to preserve himself, will fleece his unknowing board and shareholders as easily as Poll shaves the beardless Bailey, and will abscond once again.

Mr. Bailey and Poll Sweedlepipe

Chapter 29

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Commentary:

Two of the novel's most "Dickensian" — and decidedly odd — characters are the pre-pubescent "Master" Bailey, formerly of Mrs. Todgers's rooming-house near London's Monument to Great Fire of London and latterly in the employ of Chairman Tigg Montague of the Anglo-Bengalee, and barber-cum -bird fancier Poll Sweedlepipe. As the footman's livery that young Bailey wears suggests, has risen in the world, much to his friend Poll's admiration.

Enjoying everything about this peculiar but benign character, Sol Eytinge has taken unusual pains to describe the key elements of Poll's shop: his wigs on mannekins' heads, his shaving equipment, and particularly his bird cages. Poll first appears in chapter 26, so that both Phiz and Eytinge have had to conflate a later narrative moment ("Easy Shaving") with Dickens's earlier description of Poll as "a little elderly man, with a clammy, cold right-hand, from which even rabbits and birds could not remove the smell of shaving-soap. Poll had something of a bird in his nature; not of the hawk or the eagle, but of the sparrow. . . . He was not quarrelsome, though, like a sparrow; but peaceful, like the dove. In his walk he strutted: and, in this respect, he bore a faint resemblance to the pigeon" (Diamond Edition), a barber whose entire house "was one great bird's nest". Both Phiz and Eytinge show Poll's head inclined to one side, "with his eye cocked knowingly" and bald-headed. Eytinge's study brings out Poll's delicacy and tender-heartedness, as the artist captures Poll's velveteen coat and neckerchief, his barber's apron, but oddly enough not the flannel jacket that he wears when shaving customers in the great chair of his Kingsgate Street shop in the vicinity of Holborn. The precise moment realised would seem to be this:

He happened to have been sharpening his razors, which were lying open in a row, while a huge strop dangled from the wall. Glancing at these preparations, Mr Bailey stroked his chin, and a thought appeared to occur to him.

"Poll," he said, "I ain't as neat as I could wish about the gills. Being here, I may as well have a shave, and get trimmed close."

The barber stood aghast; but Mr Bailey divested himself of his neck-cloth, and sat down in the easy shaving chair with all the dignity and confidence in life. There was no resisting his manner. The evidence of sight and touch became as nothing. His chin was as smooth as a new-laid egg or a scraped Dutch cheese; but Poll Sweedlepipe wouldn't have ventured to deny, on affidavit, that he had the beard of a Jewish rabbi.

Go with the grain, Poll, all round, please," said Mr. Bailey, screwing up his face for the reception of the lather. "You may do wot you like with the bits of whisker. I don't care for 'em."

The meek little barber stood gazing at him with the brush and soap-dish in his hand, stirring them round and round in a ludicrous uncertainty, as if he were disabled by some fascination from beginning. At last he made a dash at Mr Bailey's cheek. Then he stopped again, as if the ghost of a beard had suddenly receded from his touch; but receiving mild encouragement from Mr. Bailey, in the form of an adjuration to "Go in and win," he lathered him bountifully. Mr Bailey smiled through the suds in his satisfaction. "Gently over the stones, Poll. Go a tip-toe over the pimples!"

Poll Sweedlepipe obeyed, and scraped the lather off again with particular care. Mr. Bailey squinted at every successive dab . . . .

Although it misses something of the barber's sheer wonder at his young friend's temerity, the 1867 illustration charmingly captures the essence of the peculiar relationship between the book's oddest characters, the sensitive bird-fancier Paul ("Poll") Sweedlepipe and Benjamin Bailey ("Bailey Junior"), a mutually supportive friendship between a brazen, precocious, and resilient Cockney lad who seems so knowing in the ways of the great city and the refined, delicate, almost reclusive middle-aged barber. As in the text, Poll stirs the lather round and round in the cup while the client presents his cherubic cheek and chin, and offers advice as to how best to proceed. Bailey's crisp top hat sits on the counter by the window. Bailey in Eytinge's treatment is more child-like and less of a cartoon figure than Phiz's figure, who is surrounded in the 1843 engraving by multiple examples of Poll's fascination with birds. A fine touch by Eytinge not seen in Phiz's picture is making the barber's far too large for the boy.

‘You ain’t been in the City, I suppose, sir, since we was all three there together,’ said Mrs Gamp

Chapter 29

Charles Edmund Brock

Text Illustrated:

‘I’m a-goin down with my patient in the coach this arternoon,’ she proceeded. ‘I’m a-goin to stop with him a day or so, till he gets a country nuss (drat them country nusses, much the orkard hussies knows about their bis’ness); and then I’m a-comin back; and that’s my trouble, Mr Sweedlepipes. But I hope that everythink’ll only go on right and comfortable as long as I’m away; perwisin which, as Mrs Harris says, Mrs Gill is welcome to choose her own time; all times of the day and night bein’ equally the same to me.’

During the progress of the foregoing remarks, which Mrs Gamp had addressed exclusively to the barber, Mr Bailey had been tying his cravat, getting on his coat, and making hideous faces at himself in the glass. Being now personally addressed by Mrs Gamp, he turned round, and mingled in the conversation.

‘You ain’t been in the City, I suppose, sir, since we was all three there together,’ said Mrs Gamp, ‘at Mr Chuzzlewit’s?’

‘Yes, I have, Sairah. I was there last night.’

‘Last night!’ cried the barber.

‘Yes, Poll, reether so. You can call it this morning, if you like to be particular. He dined with us.’

‘Who does that young Limb mean by “hus?”’ said Mrs Gamp, with most impatient emphasis.

‘Me and my Governor, Sairah. He dined at our house. We wos very merry, Sairah. So much so, that I was obliged to see him home in a hackney coach at three o’clock in the morning.’ It was on the tip of the boy’s tongue to relate what had followed; but remembering how easily it might be carried to his master’s ears, and the repeated cautions he had had from Mr Crimple ‘not to chatter,’ he checked himself; adding, only, ‘She was sitting up, expecting him.’

‘And all things considered,’ said Mrs Gamp sharply, ‘she might have know’d better than to go a-tirin herself out, by doin’ anythink of the sort. Did they seem pretty pleasant together, sir?’

‘Oh, yes,’ answered Bailey, ‘pleasant enough.’