The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Signalman

The Signalman

>

The Story Proper

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

This is the first of Dickens' ghost stories I can remember that actually gave me goosebumps. I did a lot of speculating as I read it -- the narrrator's descent into a "great dungeon" with a "black tunnel" that felt "as if I had left the natural world" was certainly a trip to Hell, wasn't it? Was the signalman an unwitting psychopomp, and was our narrator still among the living?

This is the first of Dickens' ghost stories I can remember that actually gave me goosebumps. I did a lot of speculating as I read it -- the narrrator's descent into a "great dungeon" with a "black tunnel" that felt "as if I had left the natural world" was certainly a trip to Hell, wasn't it? Was the signalman an unwitting psychopomp, and was our narrator still among the living? I wish Dickens had set the story up a little better. Who is the narrator, and what was he doing there? I tried to make sense of this sentence, which is our only clue about our narrator:

In me, he merely saw a man who had been shut up within narrow limits all his life, and who, being at last set free, had a newly-awakened interest in these great works.

If I was sticking with the Hell interpretation, this would make me think that the narrator was, indeed, dead (or "free" as the case may be), but the story doesn't seem to end that way, unless I'm missing something. What do you make of the signalman confusing the narrator with the specter? Was it just due to him calling out the same words, or was there a physical similarity?

I also wondered if our narrator was a representation of Jesus descending into Hell for three days, noticing that the narrator had made three visits down the path. That didn't go anywhere else for me, though. Maybe someone else can make a can make a connection.

I miss the humor - my favorite thing about Dickens. But it had no place here, and would have been incongruous with the tone of the story.

Tristram wrote: "Where do you see similarities, in style and content, with those earlier ghost stories, and where would you see differences?...."

I think the reason The Signalman gave me goosebumps, unlike others I've read, was that this story was -- how to put it? More mature? There were no goblins, à la Gabriel Grub, for example. No introductions or chit chat, as in the case of the spirits in A Christmas Carol. Our phantom is quieter and more mysterious. Dickens leaves much to the reader's imagination. But unlike To Be Read at Dusk, I feel like the pieces of the puzzle are all there for us, if we can just put them together. (Tristram's reviews tell us that Dusk was published in 1852, and The Signalman in 1866 - 14 years later.)

Mary Lou wrote: "This is the first of Dickens' ghost stories I can remember that actually gave me goosebumps. I did a lot of speculating as I read it -- the narrrator's descent into a "great dungeon" with a "black ..."

Sorry Mary Lou, I wasn't searching for a meaning for that sentence other than he was walking down a hill into a valley with a long railway tunnel in it, probably cut through the mountain I imagine, like they are here. If he went to hell poor man, it was after he died and I thought of him as a man out taking a walk, nothing more than that. Just the thing Dickens would have done day after day, and since he walked for miles wherever he happened to be I imagine he walked along the edge of a valley with a railway running through it. I know he did that when he was here, he would have had to, when he left Harrisburg he came up the river on a canal boat. The canal, parts of it are still there, is right next to the river, the Susquehanna river which is about 15 minutes away from me. He used to get out of the slow moving boat and walk along the river and also along the river are the train tracks. They are still in use. If you are outside on a quiet day you can hear the whistle as they go by.

Sorry Mary Lou, I wasn't searching for a meaning for that sentence other than he was walking down a hill into a valley with a long railway tunnel in it, probably cut through the mountain I imagine, like they are here. If he went to hell poor man, it was after he died and I thought of him as a man out taking a walk, nothing more than that. Just the thing Dickens would have done day after day, and since he walked for miles wherever he happened to be I imagine he walked along the edge of a valley with a railway running through it. I know he did that when he was here, he would have had to, when he left Harrisburg he came up the river on a canal boat. The canal, parts of it are still there, is right next to the river, the Susquehanna river which is about 15 minutes away from me. He used to get out of the slow moving boat and walk along the river and also along the river are the train tracks. They are still in use. If you are outside on a quiet day you can hear the whistle as they go by.

I loved this story, I was sorry when it was over although I couldn't think of a single thing to add to it. And now I wonder, if we had a spirit or ghost, or whatever it is giving us warnings, but only a short time before it happens, could we learn to figure out what the warning meant, or would we, like the signalman end up hit by our own train. And similar to the story of the brothers and the dying brother's pointless message to his brother, I would appreciate my spirit saying something to me like, "stay off the railroad tracks tomorrow at 8am or you'll get hit by a train!"

I first watched this story on television in 1976. It starred Denholm Elliott. Every Christmas the BBC used to dramatise a short story by M.R. James, just as the author himself used to write just one each year, and read it to his friends sitting round the fire in his Oxford College rooms. We'd anticipated and watched them since we were teenagers.

I first watched this story on television in 1976. It starred Denholm Elliott. Every Christmas the BBC used to dramatise a short story by M.R. James, just as the author himself used to write just one each year, and read it to his friends sitting round the fire in his Oxford College rooms. We'd anticipated and watched them since we were teenagers.This one wasn't familiar to me, but both my husband and I loved it! We were totally gripped and absorbed by it, and found enough of mystery and dread in the strange occurrences without needing anything else. There was an immense sense of foreboding, and it felt like a premonition, but we couldn't see how. It is claustrophobic, and having no back story adds to this feeling. And the ending was a complete shock.

I was staggered to then see the credits at the end and learn it was a story by Charles Dickens. (It was the first one to not be by M.R. James.) No symbolism ever occurred to me. It is just perfect!

Since I watched it before ever reading it, I can't really say whether or not I might have speculated about hidden meanings whilst reading the text. But I do think that if my mind was wandering so much that I was aware of them as I was reading it, then that would mean I wouldn't be as gripped by it emotionally as I hope to be by a ghost story.

I loved this story too, much better than 'To Be Read at Dusk' to be honest. Railroad tunnels are a bit creepy as is, especially the victorian ones. I can very well imagine a connection between the victorian steam-machinery, the darkness and dampness of the tunnel, the working conditions and hell - so I had the same speculation as Mary-Lou. It all sounded hellish, even without the spectre.

It was also a surrounding that must have been depressing and scary to work in night after night, and it might have been his own fear of all the things that could happen on his watch adding up year after year. Until his fear became visible - at least to him. There is nothing so scary and haunting as the human mind and it's conditions to most of us. The most impressive hurdle of fear is fear itself, bedded in lonelyness, reversed sleeping levels and stress. The longer it took, the bigger the chance got that something went wrong, and then something did, magnifying the fear. I think Dickens did a bang up job to show a burn-out to be honest.

If we go for the spectre, the easy answer is of course that it was a foreshadowing of the train driver. What I was thinking of is, what if the narrator was somehow doing reverse time (because ... I don't know, I might be overthinking this) and the signal man was an actual ghost? Then the spectre was actually a memory of the signal man's death.

Okay, I stop here, I'm really starting to overthink for now ...

It was also a surrounding that must have been depressing and scary to work in night after night, and it might have been his own fear of all the things that could happen on his watch adding up year after year. Until his fear became visible - at least to him. There is nothing so scary and haunting as the human mind and it's conditions to most of us. The most impressive hurdle of fear is fear itself, bedded in lonelyness, reversed sleeping levels and stress. The longer it took, the bigger the chance got that something went wrong, and then something did, magnifying the fear. I think Dickens did a bang up job to show a burn-out to be honest.

If we go for the spectre, the easy answer is of course that it was a foreshadowing of the train driver. What I was thinking of is, what if the narrator was somehow doing reverse time (because ... I don't know, I might be overthinking this) and the signal man was an actual ghost? Then the spectre was actually a memory of the signal man's death.

Okay, I stop here, I'm really starting to overthink for now ...

Jantine wrote: "the easy answer is of course that it was a foreshadowing of the train driver ..."

Jantine wrote: "the easy answer is of course that it was a foreshadowing of the train driver ..."Yes, this hits you right in the solar plexus at the end, shortly followed by the idea that "and the signal man was an actual ghost?"

Everything is blurred and off kilter by the ending :)

As you said Kim, Dickens used to walk and walk and walk, and muse a lot. And he loved railways! Mugby Junction and Other Stories (which this story comes from) is a set of short stories nearly all about railways, by various writers. But what is significant is that the collection was published in 1866, and we all know what had happened in the previous year ...

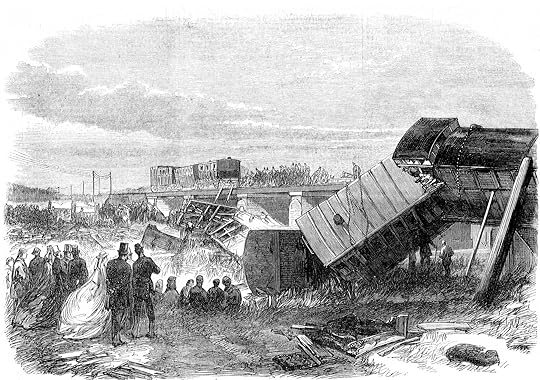

from an Engraving in the "Illustrated London News"

Yes, it was the hideous rail crash: a derailment at Staplehurst, Kent on 9 June 1865, in which Charles Dickens was such a hero rescuing passengers, at the risk of his own life. He was awarded a medal for it :)

But the memory of this event "haunted" him all his life, and he was never again happy travelling by train. If you want hidden meanings in this story, then look no further! It is cathartic. He was trying, as his son says, all his life after this event, to drive away his demons.

I too, as Tristram mentioned, have always found it significant and poignant that Dickens died exactly five years after the rail crash, to the very day.

Jantine wrote: "It was also a surrounding that must have been depressing and scary to work in night after night, and it might have been his own fear of all the things that could happen on his watch adding up year after year."

I think of it like people who worked as lighthouse keepers, I hope they brought a lot of books with them. And a piano. :-)

I think of it like people who worked as lighthouse keepers, I hope they brought a lot of books with them. And a piano. :-)

Kim wrote: "I think of it like people who worked as lighthouse keepers..."

Kim wrote: "I think of it like people who worked as lighthouse keepers..."That's a really good comparison, Kim. In the dramatisation he did read a lot, and had his own little gas-ring for making tea and coffee, but I don't remember a piano ;)

Bionic Jean wrote: ""simply retelling the story seems trite and useless to me, and since you will all have read it when I post this and since it is rather short, all the details will be fresh in your memories,"

Altho..."

Jean,

As it happens, I had written this recap prior to your post in which you complained about my "lengthy spiel", and since the new few months will leave me less time for long recaps, my future endeavours will probably be a lot shorter.

What we should not forget, though, is that there are apparently also Curiosities on board who like and read the more detailed introductions to our weekly chapters, and they seem to work well as a basis for our discussions because I try to include interesting quotations and telling details.

As to the "classroom questions", I use them, and will continue using them, in order to offer some suggestions for further discussion instead of just presenting my own thoughts at the very beginning of a discussion thread. Different moderators, different approaches - and yes, even one moderator, different approaches. Since the fable of the man, his son and the donkey was one of the stories, my grandfather told me when I was a kid, I am aware that it is impossible to please everyone, and so the best thing seems to me to think about what you are doing, try to find good reasons for doing it and then do it.

No offence meant, and I hope none taken.

Altho..."

Jean,

As it happens, I had written this recap prior to your post in which you complained about my "lengthy spiel", and since the new few months will leave me less time for long recaps, my future endeavours will probably be a lot shorter.

What we should not forget, though, is that there are apparently also Curiosities on board who like and read the more detailed introductions to our weekly chapters, and they seem to work well as a basis for our discussions because I try to include interesting quotations and telling details.

As to the "classroom questions", I use them, and will continue using them, in order to offer some suggestions for further discussion instead of just presenting my own thoughts at the very beginning of a discussion thread. Different moderators, different approaches - and yes, even one moderator, different approaches. Since the fable of the man, his son and the donkey was one of the stories, my grandfather told me when I was a kid, I am aware that it is impossible to please everyone, and so the best thing seems to me to think about what you are doing, try to find good reasons for doing it and then do it.

No offence meant, and I hope none taken.

Well, this is an interesting and perhaps even prophetic short story.

First, a side note. Our upcoming novel is Dombey and Son which is the Dickens novel that is most closely connected to the presence of the railroad. Is that eerie, or what? :-)

Next on the eerie scale is the above mentioned fact that the Staplehurst rail disaster occurred on 9th of June 1865. Exactly five years later Dickens himself died. As well as being one of the people who acted so bravely to help others Dickens returned to the coach to retrieve his manuscript for Our Mutual Friend. Dickens subsequent disquiet and dislike of the railroad after Staplehurst is understandable. That this short story was written after Staplehurst does raise the question of the extent to which the disaster played a part in the evolution of the short story.

I really enjoyed the story. No dramatically oozing blood, excessive screaming or other present cinematic techniques were required. What we have is suspense, suggestion and wonderful psychological tension all provided by words.

Could it be that the spectre’s warnings were real? Yes, I think so. Was there a ghost or spectre that the signalman really saw? Yes.

The location of the tunnel, the smoke and the sounds, or lack of clear sounds all suggest something hellish. That there were two deaths prior to the third, and that being the signalman’s, seems to suggest that magical number three. Phrases such as “he touched me on the arm with a forefinger twice, or thrice, giving a ghostly nod each time” certainly blur the line between the real and the supernatural.

Victorians loved a good ghost story. Dickens gave them one. That his death occurred 5 years to the day after a rail disaster adds fuel to any discussion of the link between the real and the supernatural.

First, a side note. Our upcoming novel is Dombey and Son which is the Dickens novel that is most closely connected to the presence of the railroad. Is that eerie, or what? :-)

Next on the eerie scale is the above mentioned fact that the Staplehurst rail disaster occurred on 9th of June 1865. Exactly five years later Dickens himself died. As well as being one of the people who acted so bravely to help others Dickens returned to the coach to retrieve his manuscript for Our Mutual Friend. Dickens subsequent disquiet and dislike of the railroad after Staplehurst is understandable. That this short story was written after Staplehurst does raise the question of the extent to which the disaster played a part in the evolution of the short story.

I really enjoyed the story. No dramatically oozing blood, excessive screaming or other present cinematic techniques were required. What we have is suspense, suggestion and wonderful psychological tension all provided by words.

Could it be that the spectre’s warnings were real? Yes, I think so. Was there a ghost or spectre that the signalman really saw? Yes.

The location of the tunnel, the smoke and the sounds, or lack of clear sounds all suggest something hellish. That there were two deaths prior to the third, and that being the signalman’s, seems to suggest that magical number three. Phrases such as “he touched me on the arm with a forefinger twice, or thrice, giving a ghostly nod each time” certainly blur the line between the real and the supernatural.

Victorians loved a good ghost story. Dickens gave them one. That his death occurred 5 years to the day after a rail disaster adds fuel to any discussion of the link between the real and the supernatural.

Peter - I have no more time for comment at the moment - but I do love your post here. You have sent a chill down my spine!

Peter - I have no more time for comment at the moment - but I do love your post here. You have sent a chill down my spine!

I cannot type in such precise wording as Jean, but as there seems to be a question about consensus and all, I want to add that I feel the same way. I admire the mods' work put into the recaps, and because of that, I sometimes feel like a lazy person if I don't read it all because it's long, and I feel an urge/compulsion to answer the questions, because they remind me of a classroom, and not because I like them. I am fully aware this is something within me, and I wouldn't dream of stoppingg to read along because of it - I like the discussions and the feeling of reading this together way too much - but I too have seen the change over the course of only a year even. And I do miss the less lengthy summaries and the feeling of equality. Please, please don't take this as a rejection, because I love this whole discussing Dickens' work together, and I am in awe of the work put into this! However, I also feel that it would be so sad if the amount of work was put into a form that in the end brings less joy than it could have brought.

Jantine - thank you so much for being brave and speaking out. It is hard, especially when you love and respect everyone in the group as much as I do (and you do, I think, too :) ).

Jantine - thank you so much for being brave and speaking out. It is hard, especially when you love and respect everyone in the group as much as I do (and you do, I think, too :) ). "And I do miss the less lengthy summaries and the feeling of equality."

I could pick out so many things you have said ... but in fact I agree with every single word you say :)

Peter wrote: That there were two deaths prior to the third, and that being the signalman’s, seems to suggest that magical number three.""

When you mentioned the magical number three, and I was already thinking of ghosts, I thought "hey, there were the three ghosts in ACC", then I remembered Jacob Marley and realized there were four.

When you mentioned the magical number three, and I was already thinking of ghosts, I thought "hey, there were the three ghosts in ACC", then I remembered Jacob Marley and realized there were four.

All this talk about June 9th got me looking for other June 9th events which took me to a book by the name of Dickens' Dreadful Almanac: A Terrible Event for Every Day of the Year , here's what it has to say about the 9th of June:

A fire, attended with the death of three children, took place on Saturday, June 9th in a house by Hackney Road. About nine o'clock flames were observed shooting from the windows by the neighbors and the screams of the children could be heard. All attempts to get to the children were unsuccessful. The flames were not extinguished until the upper part of the house was nearly burned out. A shocking sight then presented itself. Under the remains of a bedstead, in one of the upper rooms, were discovered the bodies of the three children, one a fine girl seven years of age, and two younger children, boys. They were crouched together in a heap, burned dreadfully. It is presumed that one of them had been playing with Lucifer matches, and set fire to the bed. The mother, who had gone on an errand, had in order to keep them out of the street, locked the room door. (From 1855)

A Frightful Tragedy occurred at Wilnot, Annapolis County, in the United States, on the 9th, when a Mrs. Miller, of Handley, after her husband had gone to church, walked out with her four youngest children, and having tied them to her dress, plunged with them from a cliff, and all were drowned. Her mind has been slightly deranged, but on that day she appeared unusually well. She left nine other children. (from 1850)

A fire, attended with the death of three children, took place on Saturday, June 9th in a house by Hackney Road. About nine o'clock flames were observed shooting from the windows by the neighbors and the screams of the children could be heard. All attempts to get to the children were unsuccessful. The flames were not extinguished until the upper part of the house was nearly burned out. A shocking sight then presented itself. Under the remains of a bedstead, in one of the upper rooms, were discovered the bodies of the three children, one a fine girl seven years of age, and two younger children, boys. They were crouched together in a heap, burned dreadfully. It is presumed that one of them had been playing with Lucifer matches, and set fire to the bed. The mother, who had gone on an errand, had in order to keep them out of the street, locked the room door. (From 1855)

A Frightful Tragedy occurred at Wilnot, Annapolis County, in the United States, on the 9th, when a Mrs. Miller, of Handley, after her husband had gone to church, walked out with her four youngest children, and having tied them to her dress, plunged with them from a cliff, and all were drowned. Her mind has been slightly deranged, but on that day she appeared unusually well. She left nine other children. (from 1850)

I almost forgot this:

I took you for someone else

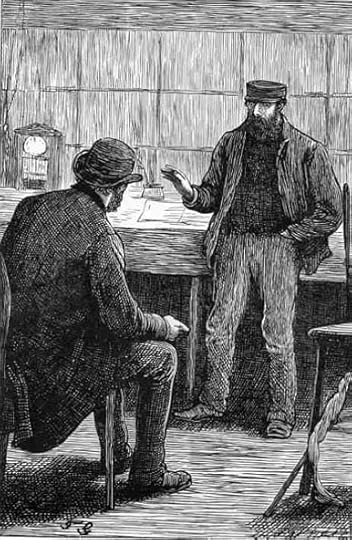

Edward Dalziel

Text Illustrated:

He wished me good night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the down Line of rails (with a very disagreeable sensation of a train coming behind me), until I found the path. It was easier to mount than to descend, and I got back to my inn without any adventure.

Punctual to my appointment, I placed my foot on the first notch of the zig-zag next night, as the distant clocks were striking eleven. He was waiting for me at the bottom, with his white light on. "I have not called out," I said, when we came close together; "may I speak now?" "By all means, sir." "Good night then, and here's my hand." "Good night, sir, and here's mine." With that, we walked side by side to his box, entered it, closed the door, and sat down by the fire.

"I have made up my mind, sir," he began, bending forward as soon as we were seated, and speaking in a tone but a little above a whisper, "that you shall not have to ask me twice what troubles me. I took you for someone else yesterday evening. That troubles me."

"That mistake?"

"No. That someone else."

"Who is it?"

"I don't know."

"Like me?"

"I don't know. I never saw the face. The left arm is across the face, and the right arm is waved. Violently waved. This way." ["Two Ghost Stories,"]

Commentary:

In the Illustrated Library Edition of 1868, the only parts of Mugby Junction that were illustrated were "The Boy at Mugby," the illustrations being Mahoney's Mugby Junction and Green's The Signal-Man — the latter illustrator presents the railway employee and his curious auditor to convey subtly the psychological aspect of "The Signal-Man." Whereas E. G. Dalziel in his Household Edition illustration for the tale of the preternatural focuses on the meeting of the inquisitive, flaneur-like narrator and his double, the distressed signalman, in "I took you for some one else yesterday evening. That troubles me", Sol Eytinge presents the reader with the framed-tale's climax, the appearance of the mysterious figure just before the railway accident that results in the signalman's being run down by a locomotive, in The Apparition.

In the original version of the short story as published in the Extra Christmas number (12 December 1866) for All the Year Round, the story of the haunted railway employee, "No. 1 Branch Line: The Signal-man," is the fourth of four pieces written by Dickens himself in the framed-tale Mugby Junction for the Extra Christmas Number of All the Year Round in 1866, the other three being "Barbox Brothers," "Barbox Brothers and Company," and "Main Line: The Boy at Mugby." This last piece and the techno-Gothic tale "The Signal-man" are the only two reprinted in the American Household Edition; in the British Household Edition, it appears as the second of "Two Ghost Stories" ahead of the Mugby Junction selections "Barbox Brothers" (Chapter I), "Barbox Brothers" (II), "Barbox Brothers and Company" (III) and "The Boy at Mugby" (V).

In Abbey's illustration, the gentlemanly narrator (a species of flanneur akin to the narrator of The Uncommercial Traveller essays of the 1860s) visits an isolated railway signal-station and makes the acquaintance of its functionary at his post near a tunnel in a cutting on the rail line near "Mugby" (the important railway junction of Rugby in Warwickshire). Although E. G. Dalziel in his Chapman and Hall Household Edition for this story has chosen much the same moment, his figures lack the animation of Abbey's and Green's, although his description of the physical setting is more successful. Mentally and emotionally at the edge, the hapless signal-man is apparently being haunted by some sort of spirit (he terms him merely "the Appearance") who has twice visited him, appearing under his warning light and crying, "Look out!" What the signal-man takes to be the the ghost's third visitation, which occurs shortly after the moment realised in the Abbey and Dalziel illustrations, proves fatal to the distraught railway employee. The ominous sense of the preternatural with which Dickens invests the story, so reminiscent of Dickens's collaborator Wilkie Collins, seems to be missing from these solid, three-dimensional closeups of the narrator and the stolid signal-man.

I took you for someone else

Edward Dalziel

Text Illustrated:

He wished me good night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the down Line of rails (with a very disagreeable sensation of a train coming behind me), until I found the path. It was easier to mount than to descend, and I got back to my inn without any adventure.

Punctual to my appointment, I placed my foot on the first notch of the zig-zag next night, as the distant clocks were striking eleven. He was waiting for me at the bottom, with his white light on. "I have not called out," I said, when we came close together; "may I speak now?" "By all means, sir." "Good night then, and here's my hand." "Good night, sir, and here's mine." With that, we walked side by side to his box, entered it, closed the door, and sat down by the fire.

"I have made up my mind, sir," he began, bending forward as soon as we were seated, and speaking in a tone but a little above a whisper, "that you shall not have to ask me twice what troubles me. I took you for someone else yesterday evening. That troubles me."

"That mistake?"

"No. That someone else."

"Who is it?"

"I don't know."

"Like me?"

"I don't know. I never saw the face. The left arm is across the face, and the right arm is waved. Violently waved. This way." ["Two Ghost Stories,"]

Commentary:

In the Illustrated Library Edition of 1868, the only parts of Mugby Junction that were illustrated were "The Boy at Mugby," the illustrations being Mahoney's Mugby Junction and Green's The Signal-Man — the latter illustrator presents the railway employee and his curious auditor to convey subtly the psychological aspect of "The Signal-Man." Whereas E. G. Dalziel in his Household Edition illustration for the tale of the preternatural focuses on the meeting of the inquisitive, flaneur-like narrator and his double, the distressed signalman, in "I took you for some one else yesterday evening. That troubles me", Sol Eytinge presents the reader with the framed-tale's climax, the appearance of the mysterious figure just before the railway accident that results in the signalman's being run down by a locomotive, in The Apparition.

In the original version of the short story as published in the Extra Christmas number (12 December 1866) for All the Year Round, the story of the haunted railway employee, "No. 1 Branch Line: The Signal-man," is the fourth of four pieces written by Dickens himself in the framed-tale Mugby Junction for the Extra Christmas Number of All the Year Round in 1866, the other three being "Barbox Brothers," "Barbox Brothers and Company," and "Main Line: The Boy at Mugby." This last piece and the techno-Gothic tale "The Signal-man" are the only two reprinted in the American Household Edition; in the British Household Edition, it appears as the second of "Two Ghost Stories" ahead of the Mugby Junction selections "Barbox Brothers" (Chapter I), "Barbox Brothers" (II), "Barbox Brothers and Company" (III) and "The Boy at Mugby" (V).

In Abbey's illustration, the gentlemanly narrator (a species of flanneur akin to the narrator of The Uncommercial Traveller essays of the 1860s) visits an isolated railway signal-station and makes the acquaintance of its functionary at his post near a tunnel in a cutting on the rail line near "Mugby" (the important railway junction of Rugby in Warwickshire). Although E. G. Dalziel in his Chapman and Hall Household Edition for this story has chosen much the same moment, his figures lack the animation of Abbey's and Green's, although his description of the physical setting is more successful. Mentally and emotionally at the edge, the hapless signal-man is apparently being haunted by some sort of spirit (he terms him merely "the Appearance") who has twice visited him, appearing under his warning light and crying, "Look out!" What the signal-man takes to be the the ghost's third visitation, which occurs shortly after the moment realised in the Abbey and Dalziel illustrations, proves fatal to the distraught railway employee. The ominous sense of the preternatural with which Dickens invests the story, so reminiscent of Dickens's collaborator Wilkie Collins, seems to be missing from these solid, three-dimensional closeups of the narrator and the stolid signal-man.

"Do you see it?" I asked him.

E. A. Abbey

Commentary:

The story of the haunted railway employee, "No. 1 Branch Line: The Signal-man," is the fourth of four pieces written by Dickens himself in the framed-tale Mugby Junction for the Extra Christmas Number of All the Year Round in 1866, the other three being "Barbox Brothers," "Barbox Brothers and Company," and "Main Line: The Boy at Mugby." This last piece and the techno-Gothic tale "The Signal-man" are the only two reprinted in the American Household Edition. In Abbey's illustration, the gentlemanly narrator (left: a species of flanneur akin to the narrator of The Uncommercial Traveller essays of the 1860s) visits an isolated railway signal-station and makes the acquaintance of its functionary (right: in company uniform) at his post near a tunnel in a cutting on the rail line near "Mugby" (the important railway junction of Rugby in Warwickshire). Mentally and emotionally at the edge, the hapless signal-man is apparently being haunted by some sort of spirit (he terms him merely "the Appearance") who has twice visited him, appearing under his warning light and crying, "Look out!" What the signal-man takes to be the the ghost's third visitation, which occurs shortly after the moment realised in Abbey's illustration, proves fatal to the distraught railway employee. The ominous sense of the preternatural with which Dickens invests the story, so reminiscent of Dickens's collaborator Wilkie Collins, is missing from this solid, three-dimensional closeup of the narrator and the agitated signal-man, who nevertheless stares fixedly at point somewhere behind the reader's right shoulder, as if Abbey means to bring the reader into the frame.

Text Illustrated:

"Will you come to the door with me, and look for it now?"

He bit his under-lip as though he were somewhat unwilling, but arose. I opened the door, and stood on the step, while he stood in the doorway. There, was the Danger-light. There, was the dismal mouth of the tunnel. There, were the high wet stone walls of the cutting. There, were the stars above them.

"Do you see it?" I asked him, taking particular note of his face. His eyes were prominent and strained; but not very much more so, perhaps, than my own had been when I had directed them earnestly towards the same spot.

"No," he answered. "It is not there."

"Agreed," said I.

We went in again, shut the door, and resumed our seats. I was thinking how best to improve this advantage, if it might be called one, when he took up the conversation in such a matter of course way, so assuming that there could be no serious question of fact between us, that I felt myself placed in the weakest of positions.

"By this time you will fully understand, sir," he said, "that what troubles me so dreadfully, is the question, What does the spectre mean?"

I was not sure, I told him, that I did fully understand.

The illustrator must necessarily shift the perspective from first person (that of the investigative narrator) to an objective or dramatic perspective that foregrounds both the narrator and the signal-man. The reader of 1876, if unfamiliar with this series of stories in the 1866 seasonal offering, may well have wondered about the context of this strange ghost story for the Industrial Age, and would not in all likelihood know that that Dickens based this incident on the Clayton Tunnel crash of 1861, although the Household Edition reader might have been aware of Dickens's own involvement in a railway viaduct accident near Staplehurst, Kent, on 9 June 1865.

A tale of the uncanny, Deborah A. Thomas calls "The Signal-man," since it involves the railway functionary's premonition of his own death. Although perhaps technically a "ghost story," it has little in common with Dickens's seasonal offerings of the 1840s. A tightly controlled first-person narrative, an exercise in economy and suspense in the manner of Edgar Allen Poe, it lacks any seasonal association; contains no heart-waring, humanitarian message; and is chiefly psychological in its interest. Indeed, so inward is the eerie story's development that it would seem to defy meaningful illustration. And, indeed, in Abbey's series for Dickens's Christmas Stories the closeup of the middle-class narrator (left, identified by his bowler hat) and the signal-man (right, in corporate uniform) conveys meaning only through the plate's juxtaposition with the letterpress on the facing page.

A far more sensational scene would have been the death of the signal-man, but, since this event occurs when the narrator is not present, Abbey may have deemed this dramatic incident unsuitable for illustration, or perhaps too violent, as the arm-waving engine-driver desperately tries to avert the collision, even as the victim ignores his entreaty, believing that the warning — phrased precisely as the phantom has uttered it on two previous occasions — is only in his mind. The picture which Abbey did provide has the virtue of focusing on the story's chief figures, but fails to create the ominous atmosphere of Dickens's text and fails to particularise the setting. Again, Abbey's Sixties style here (particularly his use of highlighting and shadow) is reminiscent of the work of British Household Edition illustrator and engraver Edward Dalziel.

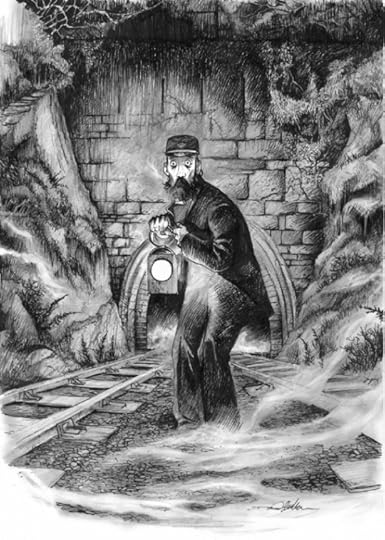

The Signal-Man

Townley Green

Text Illustrated:

He took me into his box, where there was a fire, a desk for an official book in which he had to make certain entries, a telegraphic instrument with its dial face and needles, and the little bell of which he had spoken. On my trusting that he would excuse the remark that he had been well-educated, and (I hoped I might say without offence), perhaps educated above that station, he observed that instances of slight incongruity in such-wise would rarely be found wanting among large bodies of men; that he had heard it was so in workhouses, in the police force, even in that last desperate resource, the army; and that he knew it was so, more or less, in any great railway staff. He had been, when young (if I could believe it, sitting in that, hut; he scarcely could), a student of natural philosophy, and had attended lectures; but he had run wild, misused his opportunities, gone down, and never risen again. He had no complaint to offer about that. He had made his bed and he lay upon it. It was far too late to make another.

All that I have here condensed, he said in a quiet manner, with his grave dark regards divided between me and the fire. He threw in the word "Sir" from time to time, and especially when he referred to his youth: as though to request me to understand that he claimed to be nothing but what I found him. He was several times interrupted by the little bell, and had to read off messages, and send replies. Once, he had to stand without the door, and display a flag as a train passed, and make some verbal communication to the driver. In the discharge of his duties I observed him to be remarkably exact and vigilant, breaking off his discourse at a syllable, and remaining silent until what he had to do was done.

Commentary:

Against the prosaic backdrop of the railway telegraphist's office the educated observer, identified by his middle class dress, sits nearest the reader while the wild-eyed railway employee gesticulates to indicate his puzzlement about the meaning of what he has seen and heard: the waving arm and the cautionary call "Look out, sir!" Townley Green could have chosen a more dramatic moment, but he was more interested in the contrast between the cool, detached narrator and the deeply disturbed eponymous character than in the events of the story, whose explanation may or may not be supernatural. Green even leaves the reader in doubt as to the reaction of narrator, for the illustrator has positioned "Barbox Brothers" in such a way that the reader cannot see his expression.

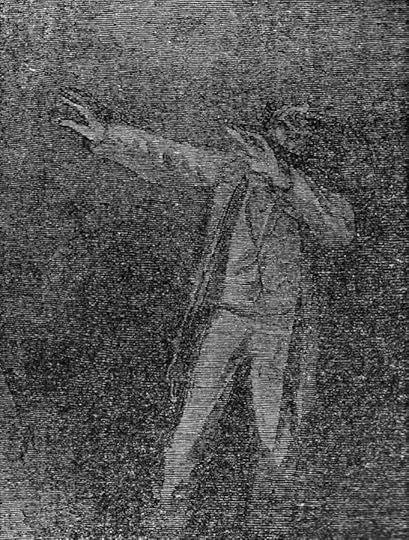

The Apparition

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Text Illustrated:

"I took you for some one else, yesterday evening. That troubles me."

"That mistake?"

"No. That some one else."

"Who is it?"

I don't know.

"Like me?"

"I don't know. I never saw the face. The left arm is across the face, and the right arm is waved, — violently waved. This way."

I followed his action with my eyes, and it was the action of an arm gesticulating with the utmost passion and vehemence, — "For God's sake, clear the way!"

"One moonlight night," said the man, "I was sitting here, when I heard a voice cry, 'Halloa! Below there!' I started up, looked from that door, and saw this Some one else standing by the red light near the tunnel, waving as I just now showed you. The voice seemed hoarse with shouting, and it cried, 'Look out! Look out!' And then again, 'Halloa! Below there! Look out!' I caught up my lamp, turned it on red, and ran towards the figure, calling, 'What's wrong? What has happened? Where?' It stood just outside the blackness of the tunnel. I advanced so close upon it that I wondered at its keeping the sleeve across its eyes. I ran right up to it, and had my hand stretched out to pull the sleeve away, when it was gone."

Commentary:

In the 1867 Diamond Edition volume, the "ghost" story is not presented in its original context as part of the framed-tale sequence entitled Mugby Junction, but as a detached, first-person narrative, with narrator not distinguished. However, Eytinge's illustration augments the text, underscoring the importance of the line spoken by the "apparition," but also adjusting the reader's interpretation of the "figure" as specifically supernatural. As the story develops, the "apparition" becomes a doppelganger foreshadowing the death of the distracted railway functionary himself at the conclusion of "The Signal-Man."

In the Illustrated Library Edition of 1868, the only part of Mugby Junction that was illustrated was "The Boy at Mugby," the wood-engraving being Mahoney's Mugby Junction — perhaps the illustrator felt that the psychological aspects of "The Signal-Man" rendered its key moment too nebulous for effective illustration. Whereas E. G. Dalziel in his Household Edition illustration for the tale of the preternatural focuses on the meeting of the inquisitive, flaneur-like narrator and the distressed signalman in "I took you for some one else yesterday evening. That troubles me", Sol Eytinge presents the reader with the framed-tale's climax, the appearance of the mysterious figure just before the railway accident that results in the signalman's being run down by a locomotive. In the original version of the short story as published in the Extra Christmas number (7 December 1866) for All the Year Round, which sold over 250,000 copies, Dickens supplemented the first four parts (the only portions that he actually wrote) with four by "other hands." Mugby Junction included the following pieces: "Barbox Brothers" and "Barbox Brothers and Co." by Charles Dickens; "Main Line. The Boy at Mugby" and "No. 1 Branch Line. The Signal-man" by Charles Dickens; "No. 2 Branch Line. The Engine-driver" by Andrew Halliday; "No. 3 Branch Line. The Compensation House" by Charles Allston Collins; "No. 4 Branch Line. The Travelling Post Office" by Hesba Stretton, and "No. 5 Branch Line. The Engineer" by Amelia B. Edwards. Here, then, late in the series of Christmas stories Dickens deviates from his established pattern in that he has not merely provided a framework that he and others fill, for he has written fully half of the number and yet as the "Conductor" written no anti-masque.

If there is no response to my message 13 to Tristram, Jantine's message 15 and Kim's comments elsewhere, it will be interesting to see the approach taken with our next read. Is Kim posting the first thread?

If there is no response to my message 13 to Tristram, Jantine's message 15 and Kim's comments elsewhere, it will be interesting to see the approach taken with our next read. Is Kim posting the first thread?Thanks as ever Kim, for digging out all these illustrations for us. I really like the early ones, although I think David Hitchcock's are too amusing. That expression on the signalman's face doesn't seem right at all! I suppose the Edward Dalziel one is a bit wooden as well.

Bionic Jean wrote: "If there is no response to my message 13 to Tristram, Jantine's message 15 and Kim's comments elsewhere, it will be interesting to see the approach taken with our next read. Is Kim posting the firs..."

Hi Jean, I'm sorry you didn't get a reply to your post from one of us when you thought you should have, I had read it and didn't see there was anything that really needed a reply, but I was wrong, so I wanted to let you know you weren't being ignored.

And Jantine, thank you for all you said, it's nice to know someone else will be skipping over the questions with me, and it's amazing how different we all are and still we're all one big family! Although as I tell Tristram when I call him family, all my family are nuts so he fits right in. :-)

Jean, Peter will be starting Dombey and I am so ready to finally be there! I'm excited to see what Peter has to say because I know how hard it was for him to get through MC, he wasn't as bad as Tristram is about TOCS, but I knew he was happy to leave Ruth Pinch with her brother and her pudding and move on to one of his favorite books. :-) I am also so, so glad he is starting because he is all ready to go and I haven't even started yet! Which now that I say that when I'm done here I'm opening that book.

I get to open next week, and then it begins, me and Tristram arguing over poor, poor Florence Dombey, I can hear it already. How one of the nicest people on earth and one of the grumpiest people on earth can get along so well I'll never figure out. :-) And for so long! I was just thinking last night that I remember his daughter being born, I can remember the day he told me. :-) And then there is Peter's first grandchild (and second). He and his wife moved back to the wonderful winters of Toronto just to be near them. I would have moved there for the wonderful winters. One of the things I look forward to each Christmas is the two phone calls I know I'll be getting, one from Peter, and one from Tristram. There is nothing like arguing over poor little Nell with his children talking in the background, his daughter even said hello to me! :-) It's just neat how we've all become family, all of us here in the group. So yes, I am looking forward to Dombey and recaps once again!

Hi Jean, I'm sorry you didn't get a reply to your post from one of us when you thought you should have, I had read it and didn't see there was anything that really needed a reply, but I was wrong, so I wanted to let you know you weren't being ignored.

And Jantine, thank you for all you said, it's nice to know someone else will be skipping over the questions with me, and it's amazing how different we all are and still we're all one big family! Although as I tell Tristram when I call him family, all my family are nuts so he fits right in. :-)

Jean, Peter will be starting Dombey and I am so ready to finally be there! I'm excited to see what Peter has to say because I know how hard it was for him to get through MC, he wasn't as bad as Tristram is about TOCS, but I knew he was happy to leave Ruth Pinch with her brother and her pudding and move on to one of his favorite books. :-) I am also so, so glad he is starting because he is all ready to go and I haven't even started yet! Which now that I say that when I'm done here I'm opening that book.

I get to open next week, and then it begins, me and Tristram arguing over poor, poor Florence Dombey, I can hear it already. How one of the nicest people on earth and one of the grumpiest people on earth can get along so well I'll never figure out. :-) And for so long! I was just thinking last night that I remember his daughter being born, I can remember the day he told me. :-) And then there is Peter's first grandchild (and second). He and his wife moved back to the wonderful winters of Toronto just to be near them. I would have moved there for the wonderful winters. One of the things I look forward to each Christmas is the two phone calls I know I'll be getting, one from Peter, and one from Tristram. There is nothing like arguing over poor little Nell with his children talking in the background, his daughter even said hello to me! :-) It's just neat how we've all become family, all of us here in the group. So yes, I am looking forward to Dombey and recaps once again!

Ditto, I'm looking forward to it too!

And y'know, this is the first and only goodreads-group I keep returning too weekly, even multiple times a week. That's how awesome all of you are ;-)

And y'know, this is the first and only goodreads-group I keep returning too weekly, even multiple times a week. That's how awesome all of you are ;-)

Kim wrote: "I almost forgot this:

I took you for someone else

Edward Dalziel

Text Illustrated:

He wished me good night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the down Line of rails (with a very ..."

Kim, as always, thanks for getting these illustrations for us.

Hmmm, the signal-man and the flaneur as connected symbolically and/or psychologically. That works for me as a possible interpretation. They do seem to be connected, to be parts of something greater, that greater being a complete, more rounded single individual. Such a character interconnection was seen in Frankenstein and then again in the decades that followed our story with Jeckyl and Hyde and then in another format with The Picture of Dorian Grey. In another slightly later form we see the pattern again with Conrad’s Kurtz.

I’m not sure, but there seems to be hints of this methodology in a form of character “double” creation that stalks through 19C British literature.

I took you for someone else

Edward Dalziel

Text Illustrated:

He wished me good night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the down Line of rails (with a very ..."

Kim, as always, thanks for getting these illustrations for us.

Hmmm, the signal-man and the flaneur as connected symbolically and/or psychologically. That works for me as a possible interpretation. They do seem to be connected, to be parts of something greater, that greater being a complete, more rounded single individual. Such a character interconnection was seen in Frankenstein and then again in the decades that followed our story with Jeckyl and Hyde and then in another format with The Picture of Dorian Grey. In another slightly later form we see the pattern again with Conrad’s Kurtz.

I’m not sure, but there seems to be hints of this methodology in a form of character “double” creation that stalks through 19C British literature.

I agree that this is a better than average ghost story. It's not about cheap thrills. It involves a mystery and intense emotions.

I agree that this is a better than average ghost story. It's not about cheap thrills. It involves a mystery and intense emotions.These lines stood out to me most:

"It struck chill to me, as if I had left the natural world."

"I perused the fixed eyes and the saturnine face, that this was a spirit, not a man."

"He had made his bed, and he lay upon it. It was far too late to make another."

There's a sense of gloom, dread, and finality.

The imagery of the signal lights seemed fatalistic to me, because they signal a train coming, and a train is hard to stop. Once it comes, you either get out the way or die.

I don't know if it's hell or limbo that Dickens is talking about, but I think it could be interpreted either way. The overall message: trains are scary, especially train crashes!

Books mentioned in this topic

Dickens' Dreadful Almanac: A Terrible Event for Every Day of the Year (other topics)Mugby Junction and Other Stories (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Denholm Elliott (other topics)

M.R. James (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

I wrote this recap together with the one on To Be Read at Dusk and since I will probably have no time tomorrow, I’ll post it now.

Writing a recap about The Signal-Man is not so easy as I thought because simply retelling the story seems trite and useless to me, and since you will all have read it when I post this and since it is rather short, all the details will be fresh in your memories, I’d say. Therefore, I am going to start my recap by quoting the first two paragraphs from the review I wrote shortly after reading it:

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

I find it rather interesting that this story can easily be linked with some of Dickens’s personal experiences and that these experiences may have contributed to his sudden death only five years later – fancy, on the very anniversary of the Staplehurst rail crash!

Unlike the ghost stories we get in Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby, The Signal-Man belongs to the later period of Dickens’s writings. Where do you see similarities, in style and content, with those earlier ghost stories, and where would you see differences?

The signal-man in the story thinks that the mysterious apparition tries to warn him of railway accidents that happen in the wake of its appearances, and he feels despair at not being able to do anything. What do you think is the reason for the spectre’s warnings, what does it try to warn the signal-man of? And what does the signal-man’s interpretation of the ghost’s intention tell us about this solitary railway worker?

Lacking the power to prevent the catastrophes he foresees and feeling anguish and sorrow for that – this is the signal-man’s plight. Do you think this is a “real” ghost story or might Dickens have wanted to express something beyond the atmosphere of mystery?

I’m looking forward a lot to hearing your thoughts on this eerie story.