The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Dombey and Son

>

D&S Chapters 17-19

Chapter 18 is titled Father and Daughter, and what a sad house we are brought back to. This is how we start:

There is a hush through Mr Dombey’s house. Servants gliding up and down stairs rustle, but make no sound of footsteps. They talk together constantly, and sit long at meals, making much of their meat and drink, and enjoying themselves after a grim unholy fashion. Mrs Wickam, with her eyes suffused with tears, relates melancholy anecdotes; and tells them how she always said at Mrs Pipchin’s that it would be so, and takes more table-ale than usual, and is very sorry but sociable. Cook’s state of mind is similar. She promises a little fry for supper, and struggles about equally against her feelings and the onions. Towlinson begins to think there’s a fate in it, and wants to know if anybody can tell him of any good that ever came of living in a corner house. It seems to all of them as having happened a long time ago; though yet the child lies, calm and beautiful, upon his little bed.

But now visitors come, and make their way upstairs bringing that "bed of rest which is so strange a one for infant sleepers". Poor Paul. Poor Florence. Poor Dombey. Dombey isn't seen, we're told, he sits in a corner of his own dark room and never seems to move when anyone is there, and when they aren't, he paces to and fro. But the servants whisper that he was heard to go upstairs in the dead night and stay in Paul's room until the sun was shining. Poor Dombey, I don't care if I said it before, I'm saying it again. The offices are shuttered, and though the firm is open there is not much business done. The clerks are indisposed to work, Perch stays long upon his errands, and as for Mr. Carker, we're told:

Mr Carker the Manager treats no one; neither is he treated; but alone in his own room he shows his teeth all day; and it would seem that there is something gone from Mr Carker’s path—some obstacle removed—which clears his way before him.

Mr. Carker scares me, him and those awful teeth of his. I wonder if he stays up late polishing them. And then comes the funeral when only Dombey, Mr. Chick, and two of the medical attendants are in attendance. This had me thinking, why did women not go to funerals in those days, and when did they start going to them? Also, there were other men I would have thought would have been there, especially Mr. Carker and his teeth, I wonder why he didn't attend the service? Or any of the other men who work for the firm. Then there is the inscription written by Dombey, saying 'beloved and only child' the man there to make the inscription had to ask him if he doesn't want 'son' instead of 'child'. Poor Florence, forgotten by her father.

When they get back from the funeral, Mr. Dombey goes right back to his empty rooms, where he will once again sit in the corner, or pace the room I suppose, and that leaves Florence with the servants, Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox. I would say poor Florence again, but I won't. Mrs. Chick now tells Florence that her father will be going into the country for a short time, and it will be a good time for her and Miss Tox to return to their own homes. Florence has been asked to visit with Sir Barnet and Lady Skettles, for a change of scene, or she may remain home by herself. Immediately Florence says she wants to stay home. I don't know what I think of leaving her home alone with just the servants, but I guess it can't be worse than being home with Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox. Oh, thinking again of Miss Tox, something happened that surprised me and made me think that she may not be as bad as I thought her to be when I first knew her, it happens here:

‘Dear aunt!’ said Florence, kneeling quickly down before her, that she might the better and more earnestly look into her face. ‘Tell me more about Papa. Pray tell me about him! Is he quite heartbroken?’

Miss Tox was of a tender nature, and there was something in this appeal that moved her very much. Whether she saw it in a succession, on the part of the neglected child, to the affectionate concern so often expressed by her dead brother—or a love that sought to twine itself about the heart that had loved him, and that could not bear to be shut out from sympathy with such a sorrow, in such sad community of love and grief—or whether she only recognised the earnest and devoted spirit which, although discarded and repulsed, was wrung with tenderness long unreturned, and in the waste and solitude of this bereavement cried to him to seek a comfort in it, and to give some, by some small response—whatever may have been her understanding of it, it moved Miss Tox. For the moment she forgot the majesty of Mrs Chick, and, patting Florence hastily on the cheek, turned aside and suffered the tears to gush from her eyes, without waiting for a lead from that wise matron.

I wonder if Miss Tox and her tender nature will last, maybe she will make a good wife for Mr. Dombey. And now Florence begins to spend her time again in her brother's room, sitting by his bed, or at the window watching the children across the street. The children who love their father, and the father who loves his children. Finally, the best thing that's happened in pages and pages happens, Toots comes to visit. Mr. Toots is a wonderful character and I hope we see more of him. But it is what he brings her that is the most wonderful thing to happen, at least if I am ever in her place, someone please bring me a dog. Nothing could be better. Mr. Toots cared enough about Paul and Florence, that he brought the dog Paul was so fond of to his sister. There is nothing like a dog to make you feel better:

Diogenes the man did not speak plainer to Alexander the Great than Diogenes the dog spoke to Florence. He subscribed to the offer of his little mistress cheerfully, and devoted himself to her service. A banquet was immediately provided for him in a corner; and when he had eaten and drunk his fill, he went to the window where Florence was sitting, looking on, rose up on his hind legs, with his awkward fore paws on her shoulders, licked her face and hands, nestled his great head against her heart, and wagged his tail till he was tired. Finally, Diogenes coiled himself up at her feet and went to sleep.

Although Miss Nipper was nervous in regard of dogs, and felt it necessary to come into the room with her skirts carefully collected about her, as if she were crossing a brook on stepping-stones; also to utter little screams and stand up on chairs when Diogenes stretched himself, she was in her own manner affected by the kindness of Mr Toots, and could not see Florence so alive to the attachment and society of this rude friend of little Paul’s, without some mental comments thereupon that brought the water to her eyes.

I adore Mr. Toots, he's my pick for Florence's future husband. But for now, Florence is left alone, and it is night, and she leaves her room, and we find that every night Florence goes to her father's door, and touches it, late at night so there is no one to see her. But this night, the door is open, and she enters the room. Florence finds her father sitting at his old table, arranging and destroying papers, but now he is just sitting, with his eyes fixed on the table, immersed in thought. He looked so worn and dejected, that Florence called out to him:

‘Papa! Papa! speak to me, dear Papa!’

He started at her voice, and leaped up from his seat. She was close before him with extended arms, but he fell back.

‘What is the matter?’ he said, sternly. ‘Why do you come here? What has frightened you?’

If anything had frightened her, it was the face he turned upon her. The glowing love within the breast of his young daughter froze before it, and she stood and looked at him as if stricken into stone.

There was not one touch of tenderness or pity in it. There was not one gleam of interest, parental recognition, or relenting in it. There was a change in it, but not of that kind. The old indifference and cold constraint had given place to something: what, she never thought and did not dare to think, and yet she felt it in its force, and knew it well without a name: that as it looked upon her, seemed to cast a shadow on her head.

Did he see before him the successful rival of his son, in health and life? Did he look upon his own successful rival in that son’s affection? Did a mad jealousy and withered pride, poison sweet remembrances that should have endeared and made her precious to him? Could it be possible that it was gall to him to look upon her in her beauty and her promise: thinking of his infant boy!

Did he? I never thought of that. Did he really see her as a rival of his son, a rival who had won in terms of health and life? Was he angry that she was still alive but his son wasn't? It never occurred to me he would have compared one to the other. Would a father really look at his daughter and wish he could change her place with her brother? How would he have felt if it was Florence who died and Paul had lived? I wonder how Paul would have felt for that matter. Would he, now spending all his time with his father have turned out just like his father? Did he know how much he was favored over her? And if he knew and she was the one who died, would he resent the way his father had treated the sister he loved? I don't know, and it's too much for my head to figure out. It didn't happen anyway, Paul died and Florence lived, and now Florence is sent back to her room by her father, telling her she was tired and had been dreaming. And so she is sent back to bed, and her father is the same to her now as he was then. He watches her as she goes up the stairs, then we're told this:

The last time he had watched her, from the same place, winding up those stairs, she had had her brother in her arms. It did not move his heart towards her now, it steeled it: but he went into his room, and locked his door, and sat down in his chair, and cried for his lost boy.

He cried for his lost boy, poor Dombey. He doesn't have his son, Florence doesn't have a brother or a father. But she does have her dog now and I'll end with him:

Diogenes was broad awake upon his post, and waiting for his little mistress.

‘Oh, Di! Oh, dear Di! Love me for his sake!’

Diogenes already loved her for her own, and didn’t care how much he showed it. So he made himself vastly ridiculous by performing a variety of uncouth bounces in the ante-chamber, and concluded, when poor Florence was at last asleep, and dreaming of the rosy children opposite, by scratching open her bedroom door: rolling up his bed into a pillow: lying down on the boards, at the full length of his tether, with his head towards her: and looking lazily at her, upside down, out of the tops of his eyes, until from winking and winking he fell asleep himself, and dreamed, with gruff barks, of his enemy.

There is a hush through Mr Dombey’s house. Servants gliding up and down stairs rustle, but make no sound of footsteps. They talk together constantly, and sit long at meals, making much of their meat and drink, and enjoying themselves after a grim unholy fashion. Mrs Wickam, with her eyes suffused with tears, relates melancholy anecdotes; and tells them how she always said at Mrs Pipchin’s that it would be so, and takes more table-ale than usual, and is very sorry but sociable. Cook’s state of mind is similar. She promises a little fry for supper, and struggles about equally against her feelings and the onions. Towlinson begins to think there’s a fate in it, and wants to know if anybody can tell him of any good that ever came of living in a corner house. It seems to all of them as having happened a long time ago; though yet the child lies, calm and beautiful, upon his little bed.

But now visitors come, and make their way upstairs bringing that "bed of rest which is so strange a one for infant sleepers". Poor Paul. Poor Florence. Poor Dombey. Dombey isn't seen, we're told, he sits in a corner of his own dark room and never seems to move when anyone is there, and when they aren't, he paces to and fro. But the servants whisper that he was heard to go upstairs in the dead night and stay in Paul's room until the sun was shining. Poor Dombey, I don't care if I said it before, I'm saying it again. The offices are shuttered, and though the firm is open there is not much business done. The clerks are indisposed to work, Perch stays long upon his errands, and as for Mr. Carker, we're told:

Mr Carker the Manager treats no one; neither is he treated; but alone in his own room he shows his teeth all day; and it would seem that there is something gone from Mr Carker’s path—some obstacle removed—which clears his way before him.

Mr. Carker scares me, him and those awful teeth of his. I wonder if he stays up late polishing them. And then comes the funeral when only Dombey, Mr. Chick, and two of the medical attendants are in attendance. This had me thinking, why did women not go to funerals in those days, and when did they start going to them? Also, there were other men I would have thought would have been there, especially Mr. Carker and his teeth, I wonder why he didn't attend the service? Or any of the other men who work for the firm. Then there is the inscription written by Dombey, saying 'beloved and only child' the man there to make the inscription had to ask him if he doesn't want 'son' instead of 'child'. Poor Florence, forgotten by her father.

When they get back from the funeral, Mr. Dombey goes right back to his empty rooms, where he will once again sit in the corner, or pace the room I suppose, and that leaves Florence with the servants, Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox. I would say poor Florence again, but I won't. Mrs. Chick now tells Florence that her father will be going into the country for a short time, and it will be a good time for her and Miss Tox to return to their own homes. Florence has been asked to visit with Sir Barnet and Lady Skettles, for a change of scene, or she may remain home by herself. Immediately Florence says she wants to stay home. I don't know what I think of leaving her home alone with just the servants, but I guess it can't be worse than being home with Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox. Oh, thinking again of Miss Tox, something happened that surprised me and made me think that she may not be as bad as I thought her to be when I first knew her, it happens here:

‘Dear aunt!’ said Florence, kneeling quickly down before her, that she might the better and more earnestly look into her face. ‘Tell me more about Papa. Pray tell me about him! Is he quite heartbroken?’

Miss Tox was of a tender nature, and there was something in this appeal that moved her very much. Whether she saw it in a succession, on the part of the neglected child, to the affectionate concern so often expressed by her dead brother—or a love that sought to twine itself about the heart that had loved him, and that could not bear to be shut out from sympathy with such a sorrow, in such sad community of love and grief—or whether she only recognised the earnest and devoted spirit which, although discarded and repulsed, was wrung with tenderness long unreturned, and in the waste and solitude of this bereavement cried to him to seek a comfort in it, and to give some, by some small response—whatever may have been her understanding of it, it moved Miss Tox. For the moment she forgot the majesty of Mrs Chick, and, patting Florence hastily on the cheek, turned aside and suffered the tears to gush from her eyes, without waiting for a lead from that wise matron.

I wonder if Miss Tox and her tender nature will last, maybe she will make a good wife for Mr. Dombey. And now Florence begins to spend her time again in her brother's room, sitting by his bed, or at the window watching the children across the street. The children who love their father, and the father who loves his children. Finally, the best thing that's happened in pages and pages happens, Toots comes to visit. Mr. Toots is a wonderful character and I hope we see more of him. But it is what he brings her that is the most wonderful thing to happen, at least if I am ever in her place, someone please bring me a dog. Nothing could be better. Mr. Toots cared enough about Paul and Florence, that he brought the dog Paul was so fond of to his sister. There is nothing like a dog to make you feel better:

Diogenes the man did not speak plainer to Alexander the Great than Diogenes the dog spoke to Florence. He subscribed to the offer of his little mistress cheerfully, and devoted himself to her service. A banquet was immediately provided for him in a corner; and when he had eaten and drunk his fill, he went to the window where Florence was sitting, looking on, rose up on his hind legs, with his awkward fore paws on her shoulders, licked her face and hands, nestled his great head against her heart, and wagged his tail till he was tired. Finally, Diogenes coiled himself up at her feet and went to sleep.

Although Miss Nipper was nervous in regard of dogs, and felt it necessary to come into the room with her skirts carefully collected about her, as if she were crossing a brook on stepping-stones; also to utter little screams and stand up on chairs when Diogenes stretched himself, she was in her own manner affected by the kindness of Mr Toots, and could not see Florence so alive to the attachment and society of this rude friend of little Paul’s, without some mental comments thereupon that brought the water to her eyes.

I adore Mr. Toots, he's my pick for Florence's future husband. But for now, Florence is left alone, and it is night, and she leaves her room, and we find that every night Florence goes to her father's door, and touches it, late at night so there is no one to see her. But this night, the door is open, and she enters the room. Florence finds her father sitting at his old table, arranging and destroying papers, but now he is just sitting, with his eyes fixed on the table, immersed in thought. He looked so worn and dejected, that Florence called out to him:

‘Papa! Papa! speak to me, dear Papa!’

He started at her voice, and leaped up from his seat. She was close before him with extended arms, but he fell back.

‘What is the matter?’ he said, sternly. ‘Why do you come here? What has frightened you?’

If anything had frightened her, it was the face he turned upon her. The glowing love within the breast of his young daughter froze before it, and she stood and looked at him as if stricken into stone.

There was not one touch of tenderness or pity in it. There was not one gleam of interest, parental recognition, or relenting in it. There was a change in it, but not of that kind. The old indifference and cold constraint had given place to something: what, she never thought and did not dare to think, and yet she felt it in its force, and knew it well without a name: that as it looked upon her, seemed to cast a shadow on her head.

Did he see before him the successful rival of his son, in health and life? Did he look upon his own successful rival in that son’s affection? Did a mad jealousy and withered pride, poison sweet remembrances that should have endeared and made her precious to him? Could it be possible that it was gall to him to look upon her in her beauty and her promise: thinking of his infant boy!

Did he? I never thought of that. Did he really see her as a rival of his son, a rival who had won in terms of health and life? Was he angry that she was still alive but his son wasn't? It never occurred to me he would have compared one to the other. Would a father really look at his daughter and wish he could change her place with her brother? How would he have felt if it was Florence who died and Paul had lived? I wonder how Paul would have felt for that matter. Would he, now spending all his time with his father have turned out just like his father? Did he know how much he was favored over her? And if he knew and she was the one who died, would he resent the way his father had treated the sister he loved? I don't know, and it's too much for my head to figure out. It didn't happen anyway, Paul died and Florence lived, and now Florence is sent back to her room by her father, telling her she was tired and had been dreaming. And so she is sent back to bed, and her father is the same to her now as he was then. He watches her as she goes up the stairs, then we're told this:

The last time he had watched her, from the same place, winding up those stairs, she had had her brother in her arms. It did not move his heart towards her now, it steeled it: but he went into his room, and locked his door, and sat down in his chair, and cried for his lost boy.

He cried for his lost boy, poor Dombey. He doesn't have his son, Florence doesn't have a brother or a father. But she does have her dog now and I'll end with him:

Diogenes was broad awake upon his post, and waiting for his little mistress.

‘Oh, Di! Oh, dear Di! Love me for his sake!’

Diogenes already loved her for her own, and didn’t care how much he showed it. So he made himself vastly ridiculous by performing a variety of uncouth bounces in the ante-chamber, and concluded, when poor Florence was at last asleep, and dreaming of the rosy children opposite, by scratching open her bedroom door: rolling up his bed into a pillow: lying down on the boards, at the full length of his tether, with his head towards her: and looking lazily at her, upside down, out of the tops of his eyes, until from winking and winking he fell asleep himself, and dreamed, with gruff barks, of his enemy.

Chapter 19 is titled Walter Goes Away, and that's exactly what happens. I've been wondering for a while what happened to Walter's parents, and who his uncle is. Is he his mother's brother? He can't be his father's brother because he and Walter have different last names. If we were told I don't remember. And I don't remember being told what happened to the rest of the family. Anyway, the last weeks had gone by quickly and now it is the day before he is to leave. We're told that Walter's heart is heavy, but he puts on a cheerful face in front of his uncle and asks what he should send him home from Barbados. His uncle replies that he should send him hope, hope that they shall meet again. Walter says he will send that, and all kinds of other things too. They then talk about Florence and Uncle Sol promises that he will keep track of her and send news of her to Walter now and then. Walter tells his uncle he had been to the house to say goodbye to Susan, and asked if she could let his uncle know now and then if Florence was well and happy. As he is saying this, his uncle suddenly jumps from his chair, and Walter, turning to see what was the matter sees Florence and Susan standing in the doorway behind him. Florence tells him she can see that his uncle is sorry to see him go, and she also will be sorry when he leaves, then I love what Susan says next:

‘Goodness knows,’ exclaimed Miss Nipper, ‘there’s a many we could spare instead, if numbers is a object, Mrs Pipchin as a overseer would come cheap at her weight in gold, and if a knowledge of black slavery should be required, them Blimbers is the very people for the sitiwation.’

Florence tells them she had to come say goodbye to Walter and tells Uncle Sol that she is anxious that he is going to be left alone, and asks if he will allow her to be his friend, and come visit him, and help him if she can. She says she would like to come visit him when she can and he can tell her everything about both him and Walter. And now she says this to Walter:

‘Oh! but, Walter,’ said Florence, ‘there is something that I wish to say to you before you go away, and you must call me Florence, if you please, and not speak like a stranger.’

‘Like a stranger!’ returned Walter, ‘No. I couldn’t speak so. I am sure, at least, I couldn’t feel like one.’

‘Ay, but that is not enough, and is not what I mean. For, Walter,’ added Florence, bursting into tears, ‘he liked you very much, and said before he died that he was fond of you, and said “Remember Walter!” and if you’ll be a brother to me, Walter, now that he is gone and I have none on earth, I’ll be your sister all my life, and think of you like one wherever we may be! This is what I wished to say, dear Walter, but I cannot say it as I would, because my heart is full.’

I'm not sure if brother was the idea that Walter had in mind, but brother it is now. And now it is time for Florence to leave, and she tells Walter that someday when her father is feeling better, she would like to tell him how much she would like to have Walter back again. Sure, like that will ever happen.

Now it is morning and Walter is ready to leave when John Carker the Junior comes to say goodbye to him. Mr. Carker thanks him for trying to be his friend, and if there was any good thing he could do on earth, he would do it for him. But he leaves when Walter urges him to come inside and meet Uncle Sol. I wonder what he will mean to the story as we go forward. There must be some reason for having him to show up for just a few lines in this chapter, something we'll find out about later. I hope so anyway. And then it really is time to go, and Walter, his uncle, and Captain Cuttle make their way to the wharf and the ship. All three went aboard this ship with the name "Son and Heir", which may not be the best name for a ship in this book. But Walter is on the ship, and Uncle Sol and Captain Cuttle are once again off the ship, after Captain Cuttle tries his best to give Walter his watch, teaspoons and sugar-tongs, all of which Walter managed to convince the Captain to keep. Then Captain Cuttle and Uncle Sol were in the smaller boat, and the Captain waved his hat at Walter until he could no longer be seen. I'll end with this:

Day after day, old Sol and Captain Cuttle kept her reckoning in the little back parlour and worked out her course, with the chart spread before them on the round table. At night, when old Sol climbed upstairs, so lonely, to the attic where it sometimes blew great guns, he looked up at the stars and listened to the wind, and kept a longer watch than would have fallen to his lot on board the ship. The last bottle of the old Madeira, which had had its cruising days, and known its dangers of the deep, lay silently beneath its dust and cobwebs, in the meanwhile, undisturbed.

‘Goodness knows,’ exclaimed Miss Nipper, ‘there’s a many we could spare instead, if numbers is a object, Mrs Pipchin as a overseer would come cheap at her weight in gold, and if a knowledge of black slavery should be required, them Blimbers is the very people for the sitiwation.’

Florence tells them she had to come say goodbye to Walter and tells Uncle Sol that she is anxious that he is going to be left alone, and asks if he will allow her to be his friend, and come visit him, and help him if she can. She says she would like to come visit him when she can and he can tell her everything about both him and Walter. And now she says this to Walter:

‘Oh! but, Walter,’ said Florence, ‘there is something that I wish to say to you before you go away, and you must call me Florence, if you please, and not speak like a stranger.’

‘Like a stranger!’ returned Walter, ‘No. I couldn’t speak so. I am sure, at least, I couldn’t feel like one.’

‘Ay, but that is not enough, and is not what I mean. For, Walter,’ added Florence, bursting into tears, ‘he liked you very much, and said before he died that he was fond of you, and said “Remember Walter!” and if you’ll be a brother to me, Walter, now that he is gone and I have none on earth, I’ll be your sister all my life, and think of you like one wherever we may be! This is what I wished to say, dear Walter, but I cannot say it as I would, because my heart is full.’

I'm not sure if brother was the idea that Walter had in mind, but brother it is now. And now it is time for Florence to leave, and she tells Walter that someday when her father is feeling better, she would like to tell him how much she would like to have Walter back again. Sure, like that will ever happen.

Now it is morning and Walter is ready to leave when John Carker the Junior comes to say goodbye to him. Mr. Carker thanks him for trying to be his friend, and if there was any good thing he could do on earth, he would do it for him. But he leaves when Walter urges him to come inside and meet Uncle Sol. I wonder what he will mean to the story as we go forward. There must be some reason for having him to show up for just a few lines in this chapter, something we'll find out about later. I hope so anyway. And then it really is time to go, and Walter, his uncle, and Captain Cuttle make their way to the wharf and the ship. All three went aboard this ship with the name "Son and Heir", which may not be the best name for a ship in this book. But Walter is on the ship, and Uncle Sol and Captain Cuttle are once again off the ship, after Captain Cuttle tries his best to give Walter his watch, teaspoons and sugar-tongs, all of which Walter managed to convince the Captain to keep. Then Captain Cuttle and Uncle Sol were in the smaller boat, and the Captain waved his hat at Walter until he could no longer be seen. I'll end with this:

Day after day, old Sol and Captain Cuttle kept her reckoning in the little back parlour and worked out her course, with the chart spread before them on the round table. At night, when old Sol climbed upstairs, so lonely, to the attic where it sometimes blew great guns, he looked up at the stars and listened to the wind, and kept a longer watch than would have fallen to his lot on board the ship. The last bottle of the old Madeira, which had had its cruising days, and known its dangers of the deep, lay silently beneath its dust and cobwebs, in the meanwhile, undisturbed.

That last chapter was heart-warming, especially after the chapter before it. I'm glad Florence will at least see a lot of Sol, and probably the captain, and between Susan and them at least gets a bit of warmth and love, even when she doesn't get it from her father.

Carther the manager truely is scary. In my mind he looks like Scar from The Lion King: an evil villain, trying to butter up those above his station, hurting the ones below him, and so hungry for power that he'd rather have everyone starving and everything collapsed than giving the power to someone who can handle it. Because chapter 18 also shows he is very incompetent as a manager; when Dombey is not there, no one works, and he is too busy polishing his teeth or something like that, feeling good about being the one on top for now, to really lead.

Carther the manager truely is scary. In my mind he looks like Scar from The Lion King: an evil villain, trying to butter up those above his station, hurting the ones below him, and so hungry for power that he'd rather have everyone starving and everything collapsed than giving the power to someone who can handle it. Because chapter 18 also shows he is very incompetent as a manager; when Dombey is not there, no one works, and he is too busy polishing his teeth or something like that, feeling good about being the one on top for now, to really lead.

Chapter 18 was sad indeed. I felt bad for Dombey crying in his room, but I don't like the way he treated Florence either. He needs to mature a bit. I loved when Toots came over with the dog. It gave me some hope after all the sadness. I like how Dickens is balancing positive and negative in a way that's more natural. I think he's gotten better since previous novels. The characters have faults but are still sympathetic, and really sad scenes are balanced with spots of brightness.

Chapter 18 was sad indeed. I felt bad for Dombey crying in his room, but I don't like the way he treated Florence either. He needs to mature a bit. I loved when Toots came over with the dog. It gave me some hope after all the sadness. I like how Dickens is balancing positive and negative in a way that's more natural. I think he's gotten better since previous novels. The characters have faults but are still sympathetic, and really sad scenes are balanced with spots of brightness.

The ship named "Son and Heir" caught my attention after Paul being associated with the ocean. I think it's important, but don't know why yet.

The ship named "Son and Heir" caught my attention after Paul being associated with the ocean. I think it's important, but don't know why yet.Poor Walter. Florence loves him like...a brother? I bet that's the last thing he wanted to hear, but he took it cordially.

Alissa wrote: "The ship named "Son and Heir" caught my attention after Paul being associated with the ocean. I think it's important, but don't know why yet.

Poor Walter. Florence loves him like...a brother? I be..."

Alissa wrote: "Chapter 18 was sad indeed. I felt bad for Dombey crying in his room, but I don't like the way he treated Florence either. He needs to mature a bit. I loved when Toots came over with the dog. It gav..."

Hi Alissa

I agree. Dickens seems much more in command of his plotting and characterization. His balancing of events, characters, moods and settings is one of the most interesting parts of the novel.

You are correct in focussing in on the name of the ship. No spoilers, but keep an eye out for the ship, its name, the suggestive meaning of its name and all other things nautical in the novel. We have oceans of nautical events yet to cross.

Poor Walter. Florence loves him like...a brother? I be..."

Alissa wrote: "Chapter 18 was sad indeed. I felt bad for Dombey crying in his room, but I don't like the way he treated Florence either. He needs to mature a bit. I loved when Toots came over with the dog. It gav..."

Hi Alissa

I agree. Dickens seems much more in command of his plotting and characterization. His balancing of events, characters, moods and settings is one of the most interesting parts of the novel.

You are correct in focussing in on the name of the ship. No spoilers, but keep an eye out for the ship, its name, the suggestive meaning of its name and all other things nautical in the novel. We have oceans of nautical events yet to cross.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 18 is titled Father and Daughter, and what a sad house we are brought back to. This is how we start:

There is a hush through Mr Dombey’s house. Servants gliding up and down stairs rustle, ..."

Kim

I’m trying to work up sympathy for Dombey but am having a bit of difficulty. Yes Dombey lost his first wife, but that event was a very minor event to Mr Dombey. Now, the loss of Paul is a major event, perhaps the most significant loss imaginable to Dombey and the firm.

Each of these losses has also been felt by Florence. Dickens clearly shows how Florence suffers from both of these deaths and how Florence wants to comfort her father. Dombey has no time for his daughter as his life is consumed by the loss of Paul. A parent should find the strength to comfort his child, to share such a lost, to be mature rather than self-serving.

It is Florence who is showing maturity in this chapter, not her father.

There is a hush through Mr Dombey’s house. Servants gliding up and down stairs rustle, ..."

Kim

I’m trying to work up sympathy for Dombey but am having a bit of difficulty. Yes Dombey lost his first wife, but that event was a very minor event to Mr Dombey. Now, the loss of Paul is a major event, perhaps the most significant loss imaginable to Dombey and the firm.

Each of these losses has also been felt by Florence. Dickens clearly shows how Florence suffers from both of these deaths and how Florence wants to comfort her father. Dombey has no time for his daughter as his life is consumed by the loss of Paul. A parent should find the strength to comfort his child, to share such a lost, to be mature rather than self-serving.

It is Florence who is showing maturity in this chapter, not her father.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 19 is titled Walter Goes Away, and that's exactly what happens. I've been wondering for a while what happened to Walter's parents, and who his uncle is. Is he his mother's brother? He can't..."

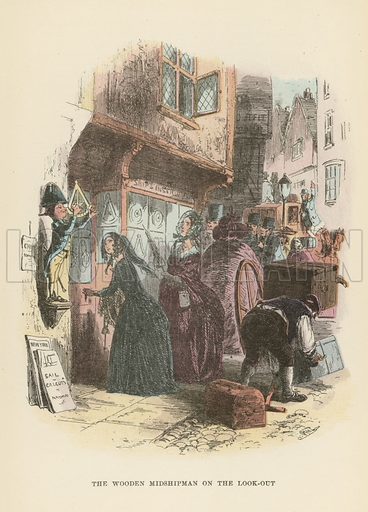

A chapter of partings. The Wooden Midshipman is a place that Florence has been to before, here she is again, and she promises to return to it in the future. Dickens has clearly made the Midshipman a place where Florence can find safety, comfort, and love. The austere nature of Mr Dombey and his home finds its opposite in the friendship and affection of Sol and Captain Cuttle at the Midshipman. Florence has two homes. What does the future hold for her?

Both James Carker and Mr Dombey are glad to see Walter shipped of to the Barbados. Both men would not shed a tear should Walter never return to England. Both men have their reasons for separating Florence from Walter.

Did you notice that Florence gave Walter a little money? Shades of Mary giving Martin Chuzzlewit a gift prior to coming to America. I wonder if there will be any other parallels between these two couples as our novel evolves?

A chapter of partings. The Wooden Midshipman is a place that Florence has been to before, here she is again, and she promises to return to it in the future. Dickens has clearly made the Midshipman a place where Florence can find safety, comfort, and love. The austere nature of Mr Dombey and his home finds its opposite in the friendship and affection of Sol and Captain Cuttle at the Midshipman. Florence has two homes. What does the future hold for her?

Both James Carker and Mr Dombey are glad to see Walter shipped of to the Barbados. Both men would not shed a tear should Walter never return to England. Both men have their reasons for separating Florence from Walter.

Did you notice that Florence gave Walter a little money? Shades of Mary giving Martin Chuzzlewit a gift prior to coming to America. I wonder if there will be any other parallels between these two couples as our novel evolves?

I thought about the same, Peter. I hope Walter will be more worthy of the gift than Martin was. And Florence certainly was the mature person, but she had to mature at a vast rate anyway, having to take care of her beloved little brother ...

This week's first chapter was extremely painful for me to read because of Captain Cuttle's awkward manoeuvres. He is clearly playing into the hands of Mr. Carker by undermining Walter's already precarious position, and at the same time he thinks he is a paragon of diplomacy and wisdom. It's so cringeworthy to see the poor Captain lean out of the window and putting his, and Walter's heads, right into the teeth-ridden mouth of the evil dragon Carker. All in all, Walter's actions in the office, the way he displeased Carker and Mr. Dombey, were probably not half as harmful as the quarter of an hour Captain Cuttle spent with Carker.

The name of the ship Walter is travelling on is indeed very conclusive. Like Peter, I will be careful not to put any spoilers into my postings here, but isn't it strange that Walter is a passenger of the Son and Heir when he is going towards the place where his new fortune (or misfortune) lies? Let's hope there is no evil omen in that ship's name!

The name of the ship Walter is travelling on is indeed very conclusive. Like Peter, I will be careful not to put any spoilers into my postings here, but isn't it strange that Walter is a passenger of the Son and Heir when he is going towards the place where his new fortune (or misfortune) lies? Let's hope there is no evil omen in that ship's name!

What struck me as further proof of Dickens's power of observation and knowledge of human nature is how he describes people's reaction to little Paul's death. Both the servants in the house, and to a lesser extent probably the people working in the office are probably sorry for Paul and his father, and yet they make use of the tragic event to treat themselves to luxuries - food, drink, and simply not doing any work - they would not have indulged in otherwise. I have found that people do react in similar ways when they learn that someone of their acquaintances have died. Unless they are really, really close to that person, they tend to regard the event with a mixture of mild grief and an inclination to a strange kind of solemnity that is not averse to partaking of a glass of something. What happens at the office during Mr. Dombey's absence, however, is clearly a case of "When the cat's away, the mice will play."

Shouldn't Mr. Carker, who I think is next in line to be Dombey, at least that's what he's planning on now that one obstacle is "removed", shouldn't he at least try to keep the people in the office working to prove that he can handle the second in command position?

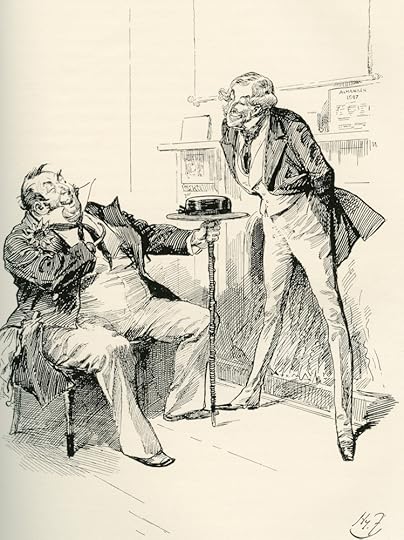

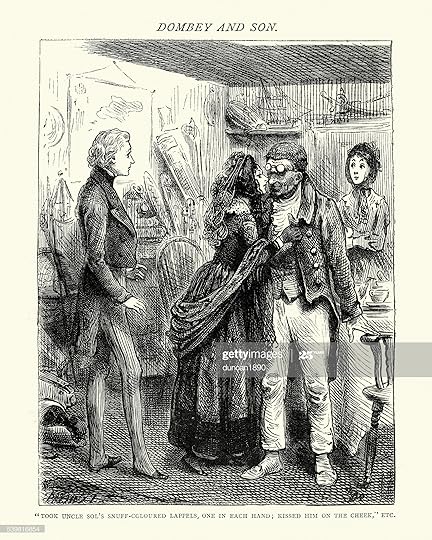

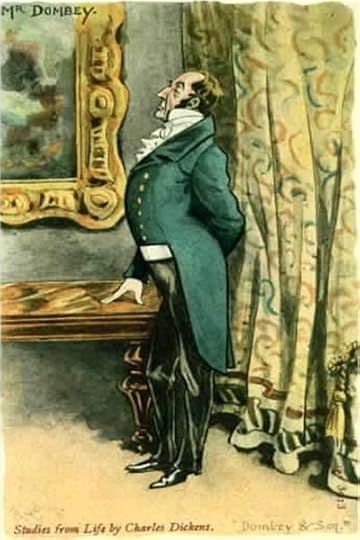

Captain Cuttle and Mr. Carker

Chapter 17

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

‘Won’t you sit down?’ said Mr Carker, smiling.

‘Thank’ee,’ returned the Captain, availing himself of the offer. ‘A man does get more way upon himself, perhaps, in his conversation, when he sits down. Won’t you take a cheer yourself?’

‘No thank you,’ said the Manager, standing, perhaps from the force of winter habit, with his back against the chimney-piece, and looking down upon the Captain with an eye in every tooth and gum. ‘You have taken the liberty, you were going to say—though it’s none—’

‘Thank’ee kindly, my lad,’ returned the Captain: ‘of coming here, on account of my friend Wal’r. Sol Gills, his Uncle, is a man of science, and in science he may be considered a clipper; but he ain’t what I should altogether call a able seaman—not man of practice. Wal’r is as trim a lad as ever stepped; but he’s a little down by the head in one respect, and that is, modesty. Now what I should wish to put to you,’ said the Captain, lowering his voice, and speaking in a kind of confidential growl, ‘in a friendly way, entirely between you and me, and for my own private reckoning, ‘till your head Governor has wore round a bit, and I can come alongside of him, is this.—Is everything right and comfortable here, and is Wal’r out’ard bound with a pretty fair wind?’

‘What do you think now, Captain Cuttle?’ returned Carker, gathering up his skirts and settling himself in his position. ‘You are a practical man; what do you think?’

The acuteness and the significance of the Captain’s eye as he cocked it in reply, no words short of those unutterable Chinese words before referred to could describe.

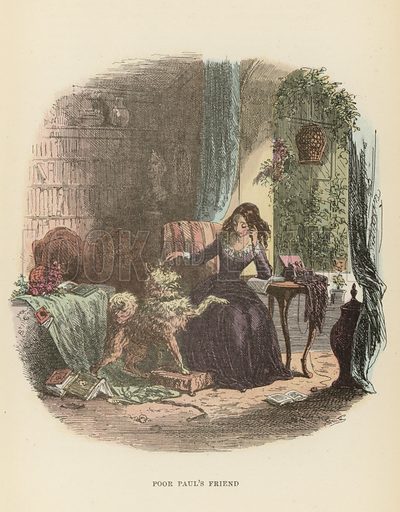

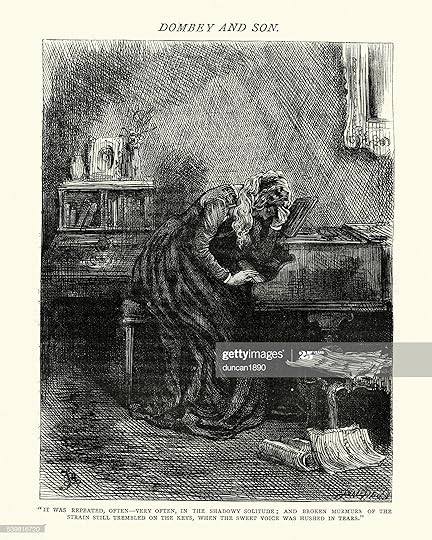

Poor Paul's Friend

Chapter 18

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

And when Diogenes, released, came tearing up the stairs and bouncing into the room (such a business as there was, first, to get him out of the cabriolet!), dived under all the furniture, and wound a long iron chain, that dangled from his neck, round legs of chairs and tables, and then tugged at it until his eyes became unnaturally visible, in consequence of their nearly starting out of his head; and when he growled at Mr Toots, who affected familiarity; and went pell-mell at Towlinson, morally convinced that he was the enemy whom he had barked at round the corner all his life and had never seen yet; Florence was as pleased with him as if he had been a miracle of discretion.

Mr Toots was so overjoyed by the success of his present, and was so delighted to see Florence bending down over Diogenes, smoothing his coarse back with her little delicate hand—Diogenes graciously allowing it from the first moment of their acquaintance—that he felt it difficult to take leave, and would, no doubt, have been a much longer time in making up his mind to do so, if he had not been assisted by Diogenes himself, who suddenly took it into his head to bay Mr Toots, and to make short runs at him with his mouth open. Not exactly seeing his way to the end of these demonstrations, and sensible that they placed the pantaloons constructed by the art of Burgess and Co. in jeopardy, Mr Toots, with chuckles, lapsed out at the door: by which, after looking in again two or three times, without any object at all, and being on each occasion greeted with a fresh run from Diogenes, he finally took himself off and got away.

‘Come, then, Di! Dear Di! Make friends with your new mistress. Let us love each other, Di!’ said Florence, fondling his shaggy head. And Di, the rough and gruff, as if his hairy hide were pervious to the tear that dropped upon it, and his dog’s heart melted as it fell, put his nose up to her face, and swore fidelity.

All this time, the bereaved father has not been seen even by his attendant; for he sits in a corner of his own dark room

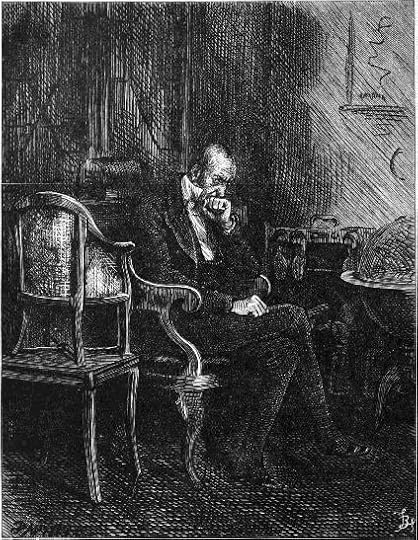

Chapter 18

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

There is a hush through Mr Dombey’s house. Servants gliding up and down stairs rustle, but make no sound of footsteps. They talk together constantly, and sit long at meals, making much of their meat and drink, and enjoying themselves after a grim unholy fashion. Mrs Wickam, with her eyes suffused with tears, relates melancholy anecdotes; and tells them how she always said at Mrs Pipchin’s that it would be so, and takes more table-ale than usual, and is very sorry but sociable. Cook’s state of mind is similar. She promises a little fry for supper, and struggles about equally against her feelings and the onions. Towlinson begins to think there’s a fate in it, and wants to know if anybody can tell him of any good that ever came of living in a corner house. It seems to all of them as having happened a long time ago; though yet the child lies, calm and beautiful, upon his little bed.

After dark there come some visitors—noiseless visitors, with shoes of felt—who have been there before; and with them comes that bed of rest which is so strange a one for infant sleepers. All this time, the bereaved father has not been seen even by his attendant; for he sits in an inner corner of his own dark room when anyone is there, and never seems to move at other times, except to pace it to and fro. But in the morning it is whispered among the household that he was heard to go upstairs in the dead night, and that he stayed there—in the room—until the sun was shining.

The Wooden Midshipman on the Look-Out

Chapter 19

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

They were at that very moment going out at the door in one of Walter’s trunks. A porter carrying off his baggage on a truck for shipment at the docks on board the Son and Heir, had got possession of them; and wheeled them away under the very eye of the insensible Midshipman before their owner had well finished speaking.

But that ancient mariner might have been excused his insensibility to the treasure as it rolled away. For, under his eye at the same moment, accurately within his range of observation, coming full into the sphere of his startled and intensely wide-awake look-out, were Florence and Susan Nipper: Florence looking up into his face half timidly, and receiving the whole shock of his wooden ogling!

I was just sitting here thinking of fathers, mostly Florence's father, but also fathers in general. I wonder if Florence thought that all fathers were like her father, so the way he acted didn't seem that strange? She had no other fathers in her life to show her any different did she? But now the family has moved in across the street with a father who obviously loves his daughters and she sees how life with a different father can be. Does this make it worse for her? When I was little I had a friend who used to spend a lot of time at my house. One day she asked me why my father never talked to me. I had never noticed before that he didn't, and started paying more attention. Since I was now paying more attention to what he was or wasn't saying to me, I was hearing things he was saying to other people, and happened to get to the top of the stairs one day when I heard my father yell at my mother "I can't help it I just don't like sick people!", to which she returned, "but she's your daughter", and I turned around and went downstairs again now knowing the reason my father never talked to me was because I was sick all the time. Something I never would have noticed if my friend hadn't pointed it out. So watching a father with his daughters across the street may not be the best thing for Florence to be doing.

One thing I do like about that family across the street is that it is almost like a house full of Little Nell children. Every day the little daughters spend the entire day waiting for the return of their father. They can't wait to see him again and wait patiently without ever getting distracted. And the dear, sweet father is never so tired that he doesn't want to spend any time on his own, but only wants to spend each and every minute with the Little Nells. And of course the children never quarrel. I'm not sure when they would find the time seeing the little angels waiting at the window all day.

Something else, these shoes that belonged to Florence. Are they never going to leave this book? Again, here they are, Walter is planning on taking them along with him on his over the sea trip. These shoes have taken the place that birds usually have in Dickens novels. I wonder where they will turn up next.

Took Uncle Sol's snuff-coloured lappels, one in each hand; kissed him on the cheek

Chapter 19

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘Why, Uncle!’ exclaimed Walter. ‘What’s the matter?’

Old Solomon replied, ‘Miss Dombey!’

‘Is it possible?’ cried Walter, looking round and starting up in his turn. ‘Here!’

Why, It was so possible and so actual, that, while the words were on his lips, Florence hurried past him; took Uncle Sol’s snuff-coloured lapels, one in each hand; kissed him on the cheek; and turning, gave her hand to Walter with a simple truth and earnestness that was her own, and no one else’s in the world!

It was repeated often - very often, in the shadowy solitude

Chapter 18

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

But it is not in the nature of pure love to burn so fiercely and unkindly long. The flame that in its grosser composition has the taint of earth may prey upon the breast that gives it shelter; but the fire from heaven is as gentle in the heart, as when it rested on the heads of the assembled twelve, and showed each man his brother, brightened and unhurt. The image conjured up, there soon returned the placid face, the softened voice, the loving looks, the quiet trustfulness and peace; and Florence, though she wept still, wept more tranquilly, and courted the remembrance.

It was not very long before the golden water, dancing on the wall, in the old place, at the old serene time, had her calm eye fixed upon it as it ebbed away. It was not very long before that room again knew her, often; sitting there alone, as patient and as mild as when she had watched beside the little bed. When any sharp sense of its being empty smote upon her, she could kneel beside it, and pray GOD—it was the pouring out of her full heart—to let one angel love her and remember her.

It was not very long before, in the midst of the dismal house so wide and dreary, her low voice in the twilight, slowly and stopping sometimes, touched the old air to which he had so often listened, with his drooping head upon her arm. And after that, and when it was quite dark, a little strain of music trembled in the room: so softly played and sung, that it was more like the mournful recollection of what she had done at his request on that last night, than the reality repeated. But it was repeated, often—very often, in the shadowy solitude; and broken murmurs of the strain still trembled on the keys, when the sweet voice was hushed in tears.

Kim wrote: "Something else, these shoes that belonged to Florence. Are they never going to leave this book? Again, here they are, Walter is planning on taking them along with him on his over the sea trip. Thes..."

Walter's taking the shoes with him is one of the things I find very, very, very eerie. It's almost like a fetish.

Walter's taking the shoes with him is one of the things I find very, very, very eerie. It's almost like a fetish.

Kim wrote: "I was just sitting here thinking of fathers, mostly Florence's father, but also fathers in general. I wonder if Florence thought that all fathers were like her father, so the way he acted didn't se..."

I am very sorry you should have had to hear such a thing from your father, Kim, even if he didn't say it outright to you. With my father, it wasn't all rosy when I was a child because in those days he clearly preferred my sister whereas I often had to suffer from his bouts of irascibility - although he didn't beat me, to make that clear. In my teenage years we got more and more into quarrelling with each other, but by now, he is in his early seventies, and we get on so well with each other that we even spend a weekend together at the coast every other autumn. Well, he was very young when he became a father, and I guess he had not sown all his wild oats at the time.

I am very sorry you should have had to hear such a thing from your father, Kim, even if he didn't say it outright to you. With my father, it wasn't all rosy when I was a child because in those days he clearly preferred my sister whereas I often had to suffer from his bouts of irascibility - although he didn't beat me, to make that clear. In my teenage years we got more and more into quarrelling with each other, but by now, he is in his early seventies, and we get on so well with each other that we even spend a weekend together at the coast every other autumn. Well, he was very young when he became a father, and I guess he had not sown all his wild oats at the time.

Kim wrote: "

Florence and Diogenes"

From Florence's facial expression I would have guessed this might be Mr. Toots's sister - but never ever Florence. The artist can't have been serious now, can he?

Florence and Diogenes"

From Florence's facial expression I would have guessed this might be Mr. Toots's sister - but never ever Florence. The artist can't have been serious now, can he?

Kim wrote: "One thing I do like about that family across the street is that it is almost like a house full of Little Nell children. Every day the little daughters spend the entire day waiting for the return of..."

The idyllic picture Dickens is painting of family life here made me groan and ask myself: Did Victorian children really sit nicely and calmly inside all day long, never quarrelling (as you said, Kim) and never breaking anything about the house. My own children are usually well-behaved but I couldn't let them alone for two hours without their falling out with each other or with the crockery. And then, how nice for the eldest daughter not to develop her faculties but to be a woman-about-the-house all day long.

The idyllic picture Dickens is painting of family life here made me groan and ask myself: Did Victorian children really sit nicely and calmly inside all day long, never quarrelling (as you said, Kim) and never breaking anything about the house. My own children are usually well-behaved but I couldn't let them alone for two hours without their falling out with each other or with the crockery. And then, how nice for the eldest daughter not to develop her faculties but to be a woman-about-the-house all day long.

I think those girls are clearly fictional, and that's okay. They are put in as a contrast to Florence's situation, and they appear that way to her. Then, when Paul was buried one of them was playing outside, so they clearly do something else besides waiting for their father - it just appears that they do to Florence, because it is such a stark contrast to what her own relationship with her father is, and we do see them painted through her eyes. So to her, she won't see them doing their needlework, or playing games, because that are things she would have done herself, as a child with her mother, or later with Susan.

Kim, I'm sorry you had that experience. You did make me realize my husband has an experience like that too. His mother is an alcoholic, one of the nasty kind, he was mentally abused as a kid. It was only when he went to university, made a good friend there who invited him over, that parents are not supposed to drink a bottle of port - or two - every day to end up in a shouting match to their kids and win it, because the kid was too scared to shout back. So yes, I think too that this family is written in the story on purpose to make Florence see how toxic her father's attitude towards her is.

On another note, I also have a way nicer story like this. My great-grandmothers wore regional garb, like this:

One day when my mom was a kid she played at a friend's place, and the friend had told her 'my grandmother will come this afternoon'. My mom had been waiting for the grandmother to arrive all day, until she had to go home, and asked 'but you said your gran would come, so where is she?' Had that woman in normal clothes been the gran all along, and my mom didn't believe it, because grans should wear clothes like in the image above! So another, way nicer story about how kids don't realize things can go differently than what they're used to in their own family.

Kim, I'm sorry you had that experience. You did make me realize my husband has an experience like that too. His mother is an alcoholic, one of the nasty kind, he was mentally abused as a kid. It was only when he went to university, made a good friend there who invited him over, that parents are not supposed to drink a bottle of port - or two - every day to end up in a shouting match to their kids and win it, because the kid was too scared to shout back. So yes, I think too that this family is written in the story on purpose to make Florence see how toxic her father's attitude towards her is.

On another note, I also have a way nicer story like this. My great-grandmothers wore regional garb, like this:

One day when my mom was a kid she played at a friend's place, and the friend had told her 'my grandmother will come this afternoon'. My mom had been waiting for the grandmother to arrive all day, until she had to go home, and asked 'but you said your gran would come, so where is she?' Had that woman in normal clothes been the gran all along, and my mom didn't believe it, because grans should wear clothes like in the image above! So another, way nicer story about how kids don't realize things can go differently than what they're used to in their own family.

Kim wrote: "One thing I do like about that family across the street is that it is almost like a house full of Little Nell children. Every day the little daughters spend the entire day waiting for the return of..."

Kim

Ah, yes. The children across the street. I found this vignette very interesting. On the surface I think the meaning is clear. There is another way to have a family dynamic. Just imagine how insular and isolated Florence would have been. A house like hers would have been grand, but it also would have been cold and austere, just like her father. Dickens makes it clear that the Dombey house exists in the shade.

I think you are right. The children across the street who wait for their father with loving impatience live on the the same street but in a different house which might as well be located on a different planet. Florence can see that different world from her house but cannot be a part of it. What to do? Where to go?

Dickens provides the answer in the form of the Wooden Midshipman. It is there Florence finds safety from her experiences with Good Mrs Brown. It is there she finds a father figure in Captain Cuttle and sees model parenting in Walter’s relationship with Sol Gills and Captain Cuttle.

While she can only watch and wonder what it means to wait for a father and celebrate nightly his return from her windowed prison in her father’s house she gets to experience at the Wooden Midshipman.

We need to remember that Florence has lost her fine clothes to Good Mrs Brown and been symbolically transformed, for the moment, by the rags Mrs Brown gives her into a street urchin. Nevertheless, Florence has found a home she could only view before from a solitary window.

Kim

Ah, yes. The children across the street. I found this vignette very interesting. On the surface I think the meaning is clear. There is another way to have a family dynamic. Just imagine how insular and isolated Florence would have been. A house like hers would have been grand, but it also would have been cold and austere, just like her father. Dickens makes it clear that the Dombey house exists in the shade.

I think you are right. The children across the street who wait for their father with loving impatience live on the the same street but in a different house which might as well be located on a different planet. Florence can see that different world from her house but cannot be a part of it. What to do? Where to go?

Dickens provides the answer in the form of the Wooden Midshipman. It is there Florence finds safety from her experiences with Good Mrs Brown. It is there she finds a father figure in Captain Cuttle and sees model parenting in Walter’s relationship with Sol Gills and Captain Cuttle.

While she can only watch and wonder what it means to wait for a father and celebrate nightly his return from her windowed prison in her father’s house she gets to experience at the Wooden Midshipman.

We need to remember that Florence has lost her fine clothes to Good Mrs Brown and been symbolically transformed, for the moment, by the rags Mrs Brown gives her into a street urchin. Nevertheless, Florence has found a home she could only view before from a solitary window.

Kim wrote: "Something else, these shoes that belonged to Florence. Are they never going to leave this book? Again, here they are, Walter is planning on taking them along with him on his over the sea trip. Thes..."

Birds and shoes. Dickens does present the most interesting riddles with everyday objects and creatures. Why would Walter be so interested in a shoe? Well, I think there is a touch of a fairy tale lingering here. Also, perhaps Walter sees the shoe as a talisman. I think many people have and value objects that resonate in some deep manner to them that others would not understand.

I think Diogenes is another case in point. He is more than a dog, more than a companion, and more than a gift to Florence. To Florence, he embodies a spirit and a life force that others such as Miss Tox, Mrs Pipchin or Major Bagstock would never understand.

Birds and shoes. Dickens does present the most interesting riddles with everyday objects and creatures. Why would Walter be so interested in a shoe? Well, I think there is a touch of a fairy tale lingering here. Also, perhaps Walter sees the shoe as a talisman. I think many people have and value objects that resonate in some deep manner to them that others would not understand.

I think Diogenes is another case in point. He is more than a dog, more than a companion, and more than a gift to Florence. To Florence, he embodies a spirit and a life force that others such as Miss Tox, Mrs Pipchin or Major Bagstock would never understand.

Tristram wrote: "Walter's taking the shoes with him is one of the things I find very, very, very eerie. It's almost like a fetish."

Tristram wrote: "Walter's taking the shoes with him is one of the things I find very, very, very eerie. It's almost like a fetish."Agreed. But I think Walter was kind of relieved to be put in the brother-role to Florence (though I don't expect it to last). Some of us are a little weirded-out by his romantic attachment to a child, but I think Walter himself is uncomfortable being attached to someone above him in class, especially with Cuttle and his uncle throwing him at her all the time.

Peter wrote: "I’m trying to work up sympathy for Dombey but am having a bit of difficulty."

Peter wrote: "I’m trying to work up sympathy for Dombey but am having a bit of difficulty."Yes, Dombey seems increasingly irredeemable. Poor Florence. But I am pleased to see her acquiring a step-family in Walter's uncle, who also needs someone now. I feel badly for him, too.

Hello, gone but back, as I am prone to do. Have a lot of catching up to do, so let's begin.

Hello, gone but back, as I am prone to do. Have a lot of catching up to do, so let's begin.--------------------------------------

The captain is funny, and what a wonderful way of talking.

As Carker's smile grows larger and larger during his meeting with the captain, I am reminded of a shark toying -- "an eye is every tooth and gum" -- with Charlie the Tuna.

Yes, and the Captain's talk is full of corrupted quotations. Without the annotations at the back of my edition, I wouldn't even have noticed, though :-)

Chapter 18

Chapter 18This is another great chapter. D writes with such clarity of purpose here. It's sad yet beautifully put together. There are several chapters we've read that are filled with finality. Flora walking up the stairs with Paul in her arms, Paul's death, and now this chapter with flora walking up the stairs again, this time alone. I don't know what the technical term is for Flora walking up the stairs with Paul in her arms and then without, but it's quite dramatic and effective.

I was hoping Flora and dad would have more of a talk. Not necessarily a more satisfying one, but more of an airing of feelings. But that's too much to hope for with Dombey. Has he had a true conversation with anyone in this book? He's condescended a couple of times to tell his sister what he thinks, but that isn't a conversation. Is he capable of one? The closest he comes is with his BFF, what's his name?, the guy he's going to the country with (vacation?).

I'm not sure I've come across another character more imprisoned by his own haughtiness than Dombey. Dickens is the author of prisons, real and psychological, and Dombey's psychological prison is overpowering. If he was Dorian Grey, I wonder what his portrait would look like? (Did someone already say that?)

I'm not sure I've come across another character more imprisoned by his own haughtiness than Dombey. Dickens is the author of prisons, real and psychological, and Dombey's psychological prison is overpowering. If he was Dorian Grey, I wonder what his portrait would look like? (Did someone already say that?)

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Is he capable of one? The closest he comes is with his BFF, what's his name?, the guy he's going to the country with (vacation?)."

You better not let Carker hear you calling someone other than him Dombey's best friend. His smile may not be so wide then.

You better not let Carker hear you calling someone other than him Dombey's best friend. His smile may not be so wide then.

I'm not afraid of Carker. He comes at me and I pull out my trusty mirror and let the reflection of his gleaming teeth bounce off it and blind him.

I'm not afraid of Carker. He comes at me and I pull out my trusty mirror and let the reflection of his gleaming teeth bounce off it and blind him.

Kim wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Is he capable of one? The closest he comes is with his BFF, what's his name?, the guy he's going to the country with (vacation?)."

You better not let Carker hear you call..."

Yeah, exactly his reaction on old Joey B. Bagshot, a frown instead of a toothy smile ;-)

You better not let Carker hear you call..."

Yeah, exactly his reaction on old Joey B. Bagshot, a frown instead of a toothy smile ;-)

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Flora walking up the stairs with Paul in her arms, Paul's death, and now this chapter with flora walking up the stairs again, this time alone. I don't know what the technical term is for Flora walking up the stairs with Paul in her arms and then without, but it's quite dramatic and effective."

In movies and series it's a motif, I believe it's called the same in books. I learned that watching The Haunting of Hill House btw, through things like Olivia wearing blue when the Bent Neck Lady would appear.

In movies and series it's a motif, I believe it's called the same in books. I learned that watching The Haunting of Hill House btw, through things like Olivia wearing blue when the Bent Neck Lady would appear.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm not sure I've come across another character more imprisoned by his own haughtiness than Dombey. Dickens is the author of prisons, real and psychological, and Dombey's psychological prison is ov..."

Xan

You are right. Dombey is within his own self-made prison. As to what his portrait would look like, that answer may be coming ...

Xan

You are right. Dombey is within his own self-made prison. As to what his portrait would look like, that answer may be coming ...

Kim wrote: "I'm not sure if brother was the idea that Walter had in mind, but brother it is now. And now it is time for Florence to leave, and she tells Walter that someday when her father is feeling better, she would like to tell him how much she would like to have Walter back again. Sure, like that will ever happen."

Kim wrote: "I'm not sure if brother was the idea that Walter had in mind, but brother it is now. And now it is time for Florence to leave, and she tells Walter that someday when her father is feeling better, she would like to tell him how much she would like to have Walter back again. Sure, like that will ever happen."Given Flow's relationship with her brother, Flow is making as solemn and as special a commitment as she can make to Walter given her age and their circumstances. When not together, which wasn't often, Flow was in Paul's mind as was Paul in Flow's. Flow and Paul as one in the world. Could there be two people closer to one another than Flow and Paul? Flow, by telling Walter that she will think of him as a brother and that he should think of her as a sister, is telling Walter how much he means to her and that he shall always be in her mind, and that she trusts he cares and thinks as much about her.

Susan Nipper playing with her bonnet strings while Flow and Paul speak in code of their love for one another is such a wonderful image. Susan playing with her bonnet in a way that emphasizes the sadness of the goodbye while at the same time adding enough humor to keep it from being too sad. Pure Dickens. I see the movie scene in my mind's eye as it must be filmed. To not prominently display Susan and her bonnet in the scene is malpractice.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Has he had a true conversation with anyone in this book?"

No, he's more like a piece of furniture. Of very old and very mahogany furniture.

No, he's more like a piece of furniture. Of very old and very mahogany furniture.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm not sure I've come across another character more imprisoned by his own haughtiness than Dombey. Dickens is the author of prisons, real and psychological, and Dombey's psychological prison is ov..."

Brilliant observation, Xan! Some foreshadowings of the prison motif of Little Dorrit here, maybe?

Brilliant observation, Xan! Some foreshadowings of the prison motif of Little Dorrit here, maybe?

Jantine wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Flora walking up the stairs with Paul in her arms, Paul's death, and now this chapter with flora walking up the stairs again, this time alone. I don't know what the techni..."

I learned it in our English lessons when our teacher kept explaining to us the difference, in writing, meaning and pronunciation, between a motive and a motif - because in German, we only have one word for it.

I learned it in our English lessons when our teacher kept explaining to us the difference, in writing, meaning and pronunciation, between a motive and a motif - because in German, we only have one word for it.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Kim wrote: "I'm not sure if brother was the idea that Walter had in mind, but brother it is now. And now it is time for Florence to leave, and she tells Walter that someday when her father is feeli..."

I love your observations here again, Xan. In fact, re-reading this book with all its vivid characters and their interconnections is like visiting an old friend.

I love your observations here again, Xan. In fact, re-reading this book with all its vivid characters and their interconnections is like visiting an old friend.

But now it is time to tell Solomon Gills, which he does, trying to put it in glowing terms and make it seem like a wonderful prospect for Walter. But Solomon doesn't find it as wonderful as the Captain had hoped, saying he would rather have the boy with him. And finding that Walter doesn't seem any more excited to go than his uncle is to see him go, the Captain gets his next bright idea. That idea is to appeal to Mr. Carker seeing he can't get to Dombey himself. He wants to find out for himself why it is that Walter is being sent so far from home. After actually getting to see Mr. Carker, I'm not sure why, after Mr. Perch tells him Carker is too busy, on checking with Mr. Carker he finds that he will see the Captain. To me it seems like one of the worst things he could have done:

Is everything right and comfortable here, and is Wal’r out’ard bound with a pretty fair wind?’

‘What do you think now, Captain Cuttle?’ returned Carker, gathering up his skirts and settling himself in his position. ‘You are a practical man; what do you think?’

The acuteness and the significance of the Captain’s eye as he cocked it in reply, no words short of those unutterable Chinese words before referred to could describe.

‘Come!’ said the Captain, unspeakably encouraged, ‘what do you say? Am I right or wrong?’

So much had the Captain expressed in his eye, emboldened and incited by Mr Carker’s smiling urbanity, that he felt himself in as fair a condition to put the question, as if he had expressed his sentiments with the utmost elaboration.

‘Right,’ said Mr Carker, ‘I have no doubt.’

‘Out’ard bound with fair weather, then, I say,’ cried Captain Cuttle.

Mr Carker smiled assent.

‘Wind right astarn, and plenty of it,’ pursued the Captain.

Mr Carker smiled assent again.

‘Ay, ay!’ said Captain Cuttle, greatly relieved and pleased. ‘I know’d how she headed, well enough; I told Wal’r so. Thank’ee, thank’ee.’

‘Gay has brilliant prospects,’ observed Mr Carker, stretching his mouth wider yet: ‘all the world before him.’

‘All the world and his wife too, as the saying is,’ returned the delighted Captain.

At the word ‘wife’ (which he had uttered without design), the Captain stopped, cocked his eye again, and putting the glazed hat on the top of the knobby stick, gave it a twirl, and looked sideways at his always smiling friend.

‘I’d bet a gill of old Jamaica,’ said the Captain, eyeing him attentively, ‘that I know what you’re a smiling at.’

Mr Carker took his cue, and smiled the more.

‘It goes no farther?’ said the Captain, making a poke at the door with the knobby stick to assure himself that it was shut.

‘Not an inch,’ said Mr Carker.

‘You’re thinking of a capital F perhaps?’ said the Captain.

Mr Carker didn’t deny it.

‘Anything about a L,’ said the Captain, ‘or a O?’

Mr Carker still smiled.

‘Am I right, again?’ inquired the Captain in a whisper, with the scarlet circle on his forehead swelling in his triumphant joy.

Mr Carker, in reply, still smiling, and now nodding assent, Captain Cuttle rose and squeezed him by the hand, assuring him, warmly, that they were on the same tack, and that as for him (Cuttle) he had laid his course that way all along. ‘He know’d her first,’ said the Captain, with all the secrecy and gravity that the subject demanded, ‘in an uncommon manner—you remember his finding her in the street when she was a’most a babby—he has liked her ever since, and she him, as much as two youngsters can. We’ve always said, Sol Gills and me, that they was cut out for each other.’

A cat, or a monkey, or a hyena, or a death’s-head, could not have shown the Captain more teeth at one time, than Mr Carker showed him at this period of their interview.

‘There’s a general indraught that way,’ observed the happy Captain. ‘Wind and water sets in that direction, you see. Look at his being present t’other day!’

‘Most favourable to his hopes,’ said Mr Carker.

‘Look at his being towed along in the wake of that day!’ pursued the Captain. ‘Why what can cut him adrift now?’

‘Nothing,’ replied Mr Carker.

‘You’re right again,’ returned the Captain, giving his hand another squeeze. ‘Nothing it is. So! steady! There’s a son gone: pretty little creetur. Ain’t there?’

‘Yes, there’s a son gone,’ said the acquiescent Carker.

‘Pass the word, and there’s another ready for you,’ quoth the Captain. ‘Nevy of a scientific Uncle! Nevy of Sol Gills! Wal’r! Wal’r, as is already in your business! And’—said the Captain, rising gradually to a quotation he was preparing for a final burst, ‘who—comes from Sol Gills’s daily, to your business, and your buzzums.’

I'm sorry Captain, but I think the only person Mr. Carker may be thinking of as a replacement for Dombey's son is himself. I can see him married to Florence right now. I don't want to think of it, but I do. And so the Captain leaves Mr. Carker, and leaves Walter in a worse place than he was before. That's what I think anyway, but time will tell. He probably should have brought flowers.