Classics and the Western Canon discussion

The Library of Greek Mythology

>

Week 1: Book 1 Theogony

From the start, this work strikes me as a terse summary starting without the origin of Ouranos and Ge, although several other religions have gotten a lot of mileage out of “in the beginning. . .” sans the origins of creator gods. The Library seems more like notes than a detailed compendium.

From the start, this work strikes me as a terse summary starting without the origin of Ouranos and Ge, although several other religions have gotten a lot of mileage out of “in the beginning. . .” sans the origins of creator gods. The Library seems more like notes than a detailed compendium.What is behind the cycle of children of the gods revolting against their parents? Also I am fascinated by the different variations of the stories and even different name spellings I have heard. Here in The Library Ge warns Zeus that his second child by Metis, a male, will usurp his role as ruler of heaven. In our recent read of Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, Prometheus had this information and Zeus did not know. I suppose the million dollar question is what is cannon and what is poetic license?

There is a lot to unpack here and throughout the rest of the work. I think supplementary material is much called for, just be sure it relates to this work. Please be sure to comment on the text of the work. Speculation on what it says about the Ancient Greek mind and culture are encouraged as well. Above all, have fun.

Just a quick comment: the index or TOC definitely reminds me of Ovid (Met.) It’s like they’re using the more or less same set of materials, but Ovid subverts them to make them serve his purpose, to tell his tales; whereas [Pseudo] “Apollodorus” did his best to refine himself out of existence, looking disinterested, objective, paring his fingernails...

Just a quick comment: the index or TOC definitely reminds me of Ovid (Met.) It’s like they’re using the more or less same set of materials, but Ovid subverts them to make them serve his purpose, to tell his tales; whereas [Pseudo] “Apollodorus” did his best to refine himself out of existence, looking disinterested, objective, paring his fingernails...

Another random thing I find interesting is that Zeus is actually the last (youngest) sibling. In most of the myths I’m familiar with, Zeus is the one in charge, the one to be obeyed, even though he’s the least of the brothers. That’s kind of unexpected.

Another random thing I find interesting is that Zeus is actually the last (youngest) sibling. In most of the myths I’m familiar with, Zeus is the one in charge, the one to be obeyed, even though he’s the least of the brothers. That’s kind of unexpected. No wonder Poseidon and Hera were constantly plotting against Zeus, being ordered around by your baby brother probably sucks. (Let me check with Joseph’s brothers, and Esau, and Cain...)

David wrote: "In our recent read of Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, Prometheus had this information and Zeus did not know. I suppose the million dollar question is what is cannon and what is poetic license?"

David wrote: "In our recent read of Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, Prometheus had this information and Zeus did not know. I suppose the million dollar question is what is cannon and what is poetic license?"I’m eager to see what Ian has to say about this, but my understanding of oral culture is that it’s unlike mass print culture precisely in that they afford many many variations. Depending on the audience and their interactions with the bard, a tale routinely gets its details twisted, adapted, omitted ... and we know many contradictory accounts existed from pottery or fragments of what eventually got written down or painted, which is, imaginably, a tiny fraction of what used to exist. I suspect canonicity wasn’t so rigid a thing back then.

Carol Dougherty says this about Apollodorus’ account of Prometheus though:

“ Apollodorus’ account is reassuringly comprehensive – it gives us a coherent story that unites and explains all the different elements of Prometheus’ myth. This sense of completeness can be misleading, however, since no Greek of the archaic or classical period would ever have encountered such a rational and comprehensive version of Prometheus’ mythic career. ”

It seems Apollodorus tried to piece together the most coherent account that makes sense, leaving out bits that don’t contribute to this coherence.

Dougherty also suggests Aeschylus altered the story to make his point ... as is routine in Greek Drama...

“ In addition to recasting Hesiod’s trickster figure as a rebel, Aeschylus adapts the myth to enhance Prometheus’ prophetic rather than deceptive powers in the play. Prometheus is the son of Gaia, not Klymene, in this play, and Aeschylus tells us that it was Prometheus, not Gaia as in Hesiod’s account, who gave Zeus the key advice that enabled him to defeat the Titans. Gaia warned her son that ‘not by strength nor overmastering force but by guile only’ would victory over the Titans be achieved, and Prometheus passed on this vital information to Zeus, who took advantage of Prometheus’ inside knowledge to triumph over the Titans and emerge as the king of the gods. In addition to having access to information that enabled Zeus’ triumph over the Titans, Prometheus holds important knowledge about Zeus’ impending marriage that would save him from downfall (an aspect also not present in Hesiod’s tale) if he should share it with Zeus – and this exclusive knowledge of the future only adds fuel to the fire of the stand-off between the two gods.

Most conspicuously, Prometheus’ name is etymologized as ‘fore- thought’ at the end of Kratos’ opening speech:

The Gods named you ‘Forethought’ falsely, for you yourself need forethought to find a way to escape from this device.”

Assuming canonicity was even a thing, it seems Aeschylus’ version wasn’t considered the “original.”

Lia wrote: "Another random thing I find interesting is that Zeus is actually the last (youngest) sibling. In most of the myths I’m familiar with, Zeus is the one in charge, the one to be obeyed, even though he..."

Lia wrote: "Another random thing I find interesting is that Zeus is actually the last (youngest) sibling. In most of the myths I’m familiar with, Zeus is the one in charge, the one to be obeyed, even though he..."This gave the Greeks themselves some problems. In Homer, Zeus seems to be the elder brother of Poseidon and Hades: one attempt to reconcile Homer and Hesiod was to argue that the two older brothers were "younger" because of their second "birth" from Kronos.

J.G. Frazer speculated (rather wildly, I think) that this account of Zeus showed that the very early Greeks ("or their ancestors") practiced ultimogeniture, in which the youngest son inherited, rather primogeniture, favoring the oldest -- which is probably implied in Homer. Ultimogeniture is actually documented in some societies, but it is pretty rare, and a single, contested, mythical datum is hardly a sound basis for ethnographic reconstructions.

(Digression. One semi-example of it is eighteenth-century New England: a model of correct parenting for Yankee farmers had the oldest son trained in a profession (clerical or legal), and the middle son(s) apprenticed to a trade, so that, for lack of anything more advantageous in life, the youngest received the family farm, and with it the problems of New England soil and early winters. If I recall correctly, John Adams, whose father insisted he become a lawyer, inherited the farm anyway when his younger brothers died before him.)

This may in fact be a stray theme -- the reversal of expectations -- incorporated into Hesiod from more general folklore about the luck of youngest sons and daughters, although that motif is (so far as I can recall) not documented until millennia later.

The situation is also complicated by, Pausanias,who, in his account of what was to be seen and heard in Roman-era Greece, reported a local story that Rhea gave Kronos a foal wrapped in swaddling-clothes instead of the infant Poseidon, and so, like Zeus, he was never swallowed. (Frazer notes that the horse was apparently digested, as it is not said to have been vomited out.)

Although we think of Poseidon mainly as a sea-god, and perhaps secondarily as the god of earthquakes (the "Earth-Shaker"), he has a strong connection with horses, which doesn't show up well in most secondary accounts of the Olympians.

David wrote: "In our recent read of Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, Prometheus had this information and Zeus did not know. I suppose the million dollar question is what is cannon and what is poetic license?. . .” s..."

David wrote: "In our recent read of Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, Prometheus had this information and Zeus did not know. I suppose the million dollar question is what is cannon and what is poetic license?. . .” s..."If I recall correctly, in that context there is a variant of the same motif. Zeus only knew that one of the goddesses was destined to give birth to a son greater than his father, and only Prometheus knew that the goddess in question was the sea-nymph Thetis. Once Zeus learned this, he quickly married Thetis off to a mortal, Peleus, and Achilles, Peleus' son, although far greater than his father, was no threat to Zeus. (This doesn't seem to be known to Homer: in the Iliad, Zeus owes Thetis favors, not because her forced her to marry a mortal, but because she warned him of a rebellion by other gods.)

David wrote: "I am fascinated by the different variations of the stories and even different name spellings I have heard.. . .” s..."

David wrote: "I am fascinated by the different variations of the stories and even different name spellings I have heard.. . .” s..."Sometimes the spelling of names reflects different practices in Anglicizing the Greek (this is very noticeable if you compare Hard's translation to Frazer's. In recent decades spellings closely reflecting the Greek originals have tended to supplant those treating the names as if they were Latin. For easy examples, the old "Uranus" is now frequently "Ouranos," and Cronus (Latin hard C, and the -us ending) is now commonly rendered Kronos.

The Romans themselves usually translated "Ouranos," "Heaven, " as Caelum, "Sky," and "interpreted" Kronos as "Saturn," after an Italian deity they thought he resembled. (Both may have been portrayed carrying a sickle.)

The punning interpretation of Kronos as "Chronos," time, supporting the "explanation" that "Time swallows his children," therefore worked well only in Greek. The words seem to be quite unrelated, but those who "civilized" the more disturbing myths by turning them into allegories of natural processes didn't require attention to linguistic niceties.

Some of the different current spellings represent different periods or dialects of Greek, e.g., "Gaia" and "Ge" (whereas "Gaea" is a Latinized version of the former -- the i/e switch is usually a giveaway). Dialect differences come up in mythological contexts like this one because, for example, Homer and Hesiod composed in a special poetic dialect, in which variant forms of words were pre-selected to fit the demands of the meter, while Apollodorus was writing prose, in a normalized form of Attic Greek, which became standard centuries after the poems were composed.

David wrote: "The Library seems more like notes than a detailed compendium.

David wrote: "The Library seems more like notes than a detailed compendium.What is behind the cycle of children of the gods revolting against their parents? . .” s..."

The Library does, in fact, seem to be a concise handbook, which summarizes plots without worrying about extraneous details like settings and characterization. It is usually taken to be a quick reference for moderately-well-educated Greeks and Romans (or better-educated ones in need of a brief refresher on some of the hundreds of stories). Several scholars have argued that it was intended to be an elementary textbook for children, but this has not gained wide acceptance.

The struggles between different generations of the gods has been a problem for a very long time -- at least since the Greeks tried connecting their myths and their morality.

We do have some evidence as to where the idea came from, if not way the Greeks chose to preserve it long enough to become an embarrassment.

Hard fails to adequately explain that the clash of the generations of the gods has, since the early twentieth century, been recognized as in some way related to the successive generations of ruling gods in the Babylonian "Epic of Creation," the "Enuma Elish" ("When on high...").

Skipping over many details, the cosmic waters Abzu (the underground fresh water on which the earth is now supposed to rest) and Tiamat (the sea) beget a generation of gods, including Anshar and Kishar, whose son Anu (Heaven) becomes their leader. These gods in turn have children, who collectively annoy the two primeval parental deities with their incessant noise. Abzu sets out to destroy them, but is defeated and killed by the magician-god Ea, who becomes lord of the water in his turn, and founds his palace on the corpse of Abzu. Ea then marries, and begets the multi-faced Marduk.

Tiamat, in response, bears a brood of monstrous offspring to to attack the gods. She makes Qingu (formerly rendered Kingu) their leader. This army intimidates the gods, including Anu and his immediate parents, but the clever Ea gets them to offer supreme power to Marduk if he can defeat Tiamat and her legions.

Marduk succeeds, and turns the body of Tiamat into the habitable world, and, using the blood of Qingu, creates mankind to serve the gods.

The story ends with the gods themselves building the primeval Temple of Marduk in Babylon -- the story turns into an ideological explanation of why Babylon should be the unquestioned supreme power (which it usually wasn't) -- culminating in a litany of the Fifty Names of Marduk (many of which are recognizably other gods, who are thus assimilated to him).

F.M. Cornford (whose translation-with-commentary of Plato's Republic was a standard college text for decades), saw that this was, however transmitted, a precedent for the rise of Zeus in Hesiod, and was connected to the Hesiodic idealization of "real" kingship (as opposed to the corrupt rulers then in power), even though it has nothing to do with hegemonic power by one or another Greek city-state. Personal morality (respect for parents) was not the main issue -- transfer of political power was the central theme, and the warring gods in both instances were being parceled out over time, instead of space, like human contenders.

Cornford's article* on this was often mentioned by later classicists, but it is only in the last couple of decades that close examination of Ancient Near Eastern influences on Greek culture has become fashionable again.

There is a major complication with Cornford's assumption of a more-or-less direct Mesopotamian influence, however.

Since the mid-twentieth century it has become increasingly apparent that this is not the only possible model for Hesiod's account of the generations of the gods and the rise of Zeus, and in fact only the general idea may have been transmitted to the Greeks. A much closer resemblance was detected to the (slowly emerging) group of Hittite texts (from modern Turkey) formerly known as "The Kumarbi Cycle," after one of the characters, and currently, using a name formerly applied to only part of the story, as "The Song of Release." Preserved in (somewhat fragmentary) cuneiform tablets, not all of which may yet have recognized as relating to the story, the story contains a mix of Mesopotamian, Hurrian (a non-Semitic language known from northern Syria and Asia Minor) and Hittite (Indo-European) elements.

This is a long, and (partly because it is incomplete) somewhat confusing account of succesive generations of gods, centering on multiple attempts to overthrow the Storm-God once he becomes king, but the most immediately compelling resemblance to the Greek account is the castration of a ruling god at the beginning. How and when this element in the wider "Kingship in Heaven" theme reached the Greeks, or at least Hesiod, is debated. It may have crossed the Aegean already in the Bronze Age, transmitted fairly directly from the Hittite Empire and its dependencies. Or it may have been picked up by Hesiod's family, which, by his own account, had returned to the Greek mainland after living in an early Greek colony in Asia Minor, where they could have been in contact with post-Imperial versions of Hittite culture, not accessible to us for lack of documentation.

(This latter explanation has the problem that it is not certain that the family history offered by "Hesiod" is an integral part of his poems, or that the "Theogony" and the more "personal" "Works and Days" are even by the same poets.)

*Actually part of a book -- see the next post for bibliography.

Bibliographical Addendum

Bibliographical AddendumI had remembered Cornford's argument concerning the relationship of the Babylonian "Enuma Elish" and Hesiod's "Theogony," but thought of it as an article in a journal, the title of which I did not recall.

Several hours later, it struck me that it was presented in a posthumous *book,* which explains why the journal title escaped me.

See Principium Sapientiae: The Origins of Greek Philosophical Thought, Cambridge University Press, 1952.

The chapters relevant to us (out of sixteen) are:

XII. Hesiod's Hymn to Zeus

XIII. Life story of Zeus

XIV. Cosmogonical myth and ritual

XV. The Hymn to Marduk and the Hymn to Zeus

The book was unfinished at Cornford's death, and was edited for posthumous publication by W.K.C. Guthrie, at the urging of another colleague of Cornford's, E.R. Dodds, who thought that Cornford's work was important to classicists.

It got a fierce review in a philosophical (not classical) journal, in which the reviewer objected to the sketchiness of the notes, the diversity of references to other cultures, and the lack of a formal conclusion, dismissing Guthrie's apologies for publishing the fragment in this condition. That Cornford was breaking new ground in the somewhat limited purview of traditional classical studies was apparently not relevant.

It is nevertheless a very interesting book, even if some of its conclusions don't stand up equally well, and in places it has been dated by later discoveries. It can be found for sale, often at what seem to me inflated prices, but I located a downloadable free copy at https://epdf.pub/principium-sapientia...

Lia wrote: "Another random thing I find interesting is that Zeus is actually the last (youngest) sibling. In most of the myths I’m familiar with, Zeus is the one in charge, the one to be obeyed, even though he..."

Lia wrote: "Another random thing I find interesting is that Zeus is actually the last (youngest) sibling. In most of the myths I’m familiar with, Zeus is the one in charge, the one to be obeyed, even though he..."For an immortal being, does birth order really matter? Incestuous marriages don't seem to matter either.

Ian wrote: "The struggles between different generations of the gods has been a problem for a very long time -- at least since the Greeks tried connecting their myths and their morality."

Ian wrote: "The struggles between different generations of the gods has been a problem for a very long time -- at least since the Greeks tried connecting their myths and their morality."I have always found the god's contending against each other to be interesting. At one point Socrates uses this contention in Euthyphro to suggest that piety is not what the god's say because they do not agree with each other. In The Republic Socrates insists the gods were not in contention with each other and wishes to censor the poets who suggest otherwise in order to keep order by preventing the emulation of the factional behavior by their role model gods.

David wrote: "For an immortal being, does birth order really matter? Incestuous marriages don't seem to matter either...."

David wrote: "For an immortal being, does birth order really matter? Incestuous marriages don't seem to matter either...."I hope Ian will comment on this as well, but IIRC, in the Homeric Hymns, Hermes eventually peacefully settled in the Pantheon by acknowledging some degree of subordination to his elder brother Apollo.

Also, in the Odyssey, Zeus spoke to Poseidon about punishing the Phaeacians for helping Odysseus. Poseidon complains about not being honored sufficiently, Zeus seems to suggest that’s not possible because he’s the elder:

(13.144)

Storm God Zeus exclaimed,

“Earth-Shaker! How absurd! The gods

do not dishonor you; it would be hard

to disrespect an elder so high-ranking.

(Emily Wilson trans.)

In the footnote, Wilson did clarify:

“ There are different traditions about whether Zeus or Poseidon was the elder brother. The text here might suggest that Poseidon is the older, or only that he is one of the older generation of Olympian gods (in contrast to relative newcomers like Aphrodite and Dionysus).”

So we don’t know for sure, but it’s possible that Zeus also settled his long feud with Poseidon by acknowledging his elder and more entitled status.

Cphe wrote: "In the foreword there is some controversy as to when the library was written and perhaps some interpretation is lost in translation. How many oracles were there? The text says oracles but Apollo on..."

Cphe wrote: "In the foreword there is some controversy as to when the library was written and perhaps some interpretation is lost in translation. How many oracles were there? The text says oracles but Apollo on..."A somewhat (as usual) digressive response:

There were a multitude of oracles, involving a variety of gods and "divine heroes" scattered through the Greek world -- the Greek mainland proper, the Aegean Islands, the coastal regions of Asia Minor (where it was colonized by the Greeks), and Italy (likewise: some of these were later adopted by the Romans).

The most prominent, and richest, was Apollo's at Delphi, but he had several others, and the Oracle of Zeus at Dodona was also regarded as extremely venerable. (Delphi supposedly had been an oracular site even before Apollo took it over, so there could have been a dispute over priority between the two locations, but Dodona doesn't seem to have made an issue of it.)

Delphi was richest because, in general, a fee was charged for oracular services, on top of which satisfied customers were expected to make generous offerings ("votives") to the oracle in question. At times Delphi catered to very wealthy kings and prosperous cities, who were either very grateful to Apollo, or wanted to show everyone how rich and pious they were (or both).

Delphi, and probably other oracles, were also suspected of accepting bribes for giving pre-determined responses, which suggests that some people used them mainly for purposes other than foretelling the future -- in some cases, for making it.

There was a notorious case in pre-classical times in which the Delphic oracle was (supposedly) bribed to give no response to questions by the Spartans except to tell them to liberate Athens from its tyrants.

The Spartans eventually got the message, then tried to run Athens themselves, with a puppet oligarchy, and ultimately suffered a humiliating defeat by the Athenian masses, inaugurating the first stage of their new democracy (see Herodotus).

In any case, these "votive offerings," no matter why they were given, were stored in museum-like "treasuries," each usually named for the donor city. Their masses of precious metal attracted the attention of cash-starved neighboring cities. Cities were free to withdraw their own offerings -- on condition that it was eventually replaced by something of equal or greater value -- but taking from donations form other cities was profanation, and a major instance of it brought about a prolonged "Sacred War," which eventually drew in a good deal of Greece.

Pausanias, whose Rome-era description of Greece I have mentioned before, has interesting accounts of the inscriptions at Delphi (and elsewhere) dedicating offerings that were no longer there. In some cases, his accounts have been confirmed archaeologically. There is no way of telling from these how accurate the inscriptions were, just that Pausanias probably really did see them -- which had been challenged by some nineteenth-century German scholars, who had decided that he was a fraud when they found his directions confusing when they tried to follow him on the ground.

(It didn't please nationalistic German professors to be told that British military engineers, with less Greek but more practical experience at finding their way in rough country, insisted that Pausanias was pretty reliable, once the intervening centuries were taken into account, and you got the hang of how he described routes from one place to another.)

Getting back to oracles. They went into a decline under Roman rule, partly because the Romans deliberately disrupted Greek travel from one place to another, to derail anti-Roman conspiracies, but it was more widespread than that, and people like Plutarch wrote essays on the problem. I suspect that the lack of big questions that Greeks had any say in accounted for a decline of interest in at least the major sites. Why spend money to find out if something was going to be good or bad, if the Romans were determined to do it anyway?

The Christians closed down those oracles remaining in late antiquity -- or, in some cases, may have co-opted popular habits, and turned them into the shrines of saints, instead.

Minor oracles, often associated with heroes instead of gods were probably too numerous to readily count, and their fame was usually strictly local. Pausanias, whose Roman-era description of Greece I mentioned earlier, describes some of them, including examples that seem pretty creepy, and I would think it would take strong motivation to use some of them.

Although we mainly associate Greek oracles with telling the future -- their main role in the stories we tend to remember and repeat -- they were often consulted on matters of ritual, and whether the gods favored or disfavored a course of action -- satisfactory future results not guaranteed. These would have been long-term projects: for the short term, the gods could be consulted through diviners, who noted things like the flights of significant birds (like an eagle on the right) on the eve of battle. Another method was to consult the entrails of a sacrifice.

The interpreters of these sacrifices were suspected of slanting their results to what whoever was paying for the consultation wanted to hear. Xenophon, who claimed to have been present for many such consultations, and had learned quite a bit about what the shapes meant, liked to see the entrails for himself, to be sure the diviner was giving the straight deal.

This comes up several times in his account of the retreat of the 10,000 from the clutches of the Persian Empire, which, along with a great deal else, gives an interesting view of the practical religion of an Athenian aristocrat. (By the way, Socrates is supposed to have chided him for asking the wrong question when he consulted an oracle.)

Lia wrote: "... IIRC, in the Homeric Hymns, Hermes eventually peacefully settled in the Pantheon by acknowledging some degree of subordination to his elder brother Apollo., ..."

Lia wrote: "... IIRC, in the Homeric Hymns, Hermes eventually peacefully settled in the Pantheon by acknowledging some degree of subordination to his elder brother Apollo., ..."That is a good general description, but Hermes insists on first being acknowledged as an Olympian, and then appeases Apollo for the theft of his cattle by giving him his newly-invented lyre, in exchange for which he gets a share in the role of divine protector of flocks and herds, and in some forms of divination (which never seem to amount to much elsewhere, but may have been useful for Hermes in his role as a divine thief!). The role as god of flocks and herds, which may have been his from the beginning, seems to account for the symbolism of his becoming the father of Pan, the Arcadian goat-god, although that relationship was sometimes contested.

The Zeus/Poseidon squaring off in the Odyssey is complicated by the fact that we are never told their birth order there, and are left to wonder if it is supposed to be the same as in the Iliad, where Zeus is explicitly the eldest. (It is clear that Athena, as daughter of Zeus, is technically subordinate to her uncle Poseidon, and has to work around him, but that is no help.)

Perhaps whoever was most responsible for the Odyssey as we now have it was confronted with the issue, with different traditions saying one or the other, and avoided taking sides so as not to annoy any audience which "knew" that it was the other way around.

Ian wrote: "The role as god of flocks and herds, which may have been his from the beginning, seems to account for the symbolism of his becoming the father of Pan, the Arcadian goat-god, ..."

Ian wrote: "The role as god of flocks and herds, which may have been his from the beginning, seems to account for the symbolism of his becoming the father of Pan, the Arcadian goat-god, ..."Well, that would explain why I subconsciously find Hermes so terrifying (on top of all the sadistic things he did to mortals as a sidekick or a messenger!...please don’t tell Hermes I said this!)

Ian wrote: “Perhaps whoever was most responsible for the Odyssey as we now have it was confronted with the issue, with different traditions saying one or the other, and avoided taking sides so as not to annoy any audience which "knew" that it was the other way around”

I read that bards and myth makers did not generally “respect” or presume “authority” of what the other bards were singing, but they do adjust their narratives depending on their audiences. Maybe this is why Socrates was against writing ... the Odyssey as we know it is the only version that survived, and for all we know it might not be the most mainstream or traditional or dominant take. I do think the writer of the Odyssey tried to imitate the writer of the Iliad though, so maybe he made more efforts to harmonize his version with that... but that would make it unlikely that he made Poseidon the Elder in the Odyssey.

Maybe we can gloss over it by taking up the vomit-rebirth order narrative and make Poseidon both elder and younger 🤷🏼♀️

David wrote: "The Children of Poseidon; Demeter and Persephone

David wrote: "The Children of Poseidon; Demeter and Persephone The story of Demeter and Persephone is told and I found the summary treatment really lacking. What does eating pomegranates have to do with forcing Persephone to stay with Pluto for a third, or half, of the year?"

I’ve read / heard multiple conflicting explanations from profs / classicists, that is, I don’t think there is a definitive explanation.

The first one I heard in an introductory course lecture was that eating or drinking anything at all would complete the ritual and make her formally his wedded wife. I later tried to find academic writings that support that take and all I can find is classicists citing non-Greek ancient cultures that have similar tales of tricking maidens and young men into marriage by offering them water or food.

A similar but more convoluted take is that it involves superstitious believes about many-seeded fruits having aphrodisiac or fertility-enhancing properties, and the pomegranates is presumed to have magical properties (like Hermes’ Moly). The meaning of the verb used to describe what Pluto did with the seed in Homeric Hymn is debated, it seems to involve some kind of back and forth or circular movements. Some classicists suggests Pluto rubbed the seed or made circular movement to complete a charm that would bind Persephone (i.e. make her fall in love) to him... which ... kind of implies she fell in love with her abductor 🙄

We know the Greeks had rituals that must be performed when a child is born for the baby to formally be recognized as part of the household, it’s possible that there were similar rituals (like doing something with pomegranates seeds at weddings) that used to be common knowledge.

I skipped over the incestuous marriages bit.

I skipped over the incestuous marriages bit.This is a problem whenever you start off with a small group of primeval beings (Genesis dances around the problem: for example, who would Cain and Abel have married? One explanation was that each had a twin sister....)

It is a major problem with polytheistic systems, avoidable only by having a bunch of completely unrelated original gods, and that is awkward -- and unlikely to arise until someone began assembling stories, and realized that there might be a problem.

From India, there is a story of the god Shiva suddenly appearing to shoot an arrow at the creator-god Brahma, who is pursuing his own daughter. This avoids primeval incest, but leaves out where Shiva came from if he was not related to Brahma. Of course, in the full mythology they both had existed in innumerable previous cosmic cycles, but that only postpones the question.

(By the way, Brahma mainly creates through yoga-like ascetic exercises, but I've digressed far enough along those lines already.)

When the (officially) Christian Icelander Snorri Sturluson, at the far side of the Indo-European diaspora, tried to set down the stories of the Norse gods, he avoided obvious incest among the Aesir by making the males and females all descendants of various different giants or giantesses, but he ran into a problem with the rival pantheon of the Vanir, who apparently were explicitly said to practice brother-sister marriages, so he works that into the story.

Lia wrote: "David wrote: "The Children of Poseidon; Demeter and Persephone

Lia wrote: "David wrote: "The Children of Poseidon; Demeter and Persephone The story of Demeter and Persephone is told and I found the summary treatment really lacking. What does eating pomegranates have to d..."

Pomegranate seeds may only be a colorful embellishment -- "Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative" (W. S Gilbert, "The Mikado").

There is, as Frazer noted, a very widespread belief that it is dangerous to eat or drink anything in the world of the dead, or in the otherworld, whether populated by gods or lesser beings -- in other words, avoid accepting anything from the fairy-folk, or their local equivalent, let alone the God of the Dead.

This idea probably was already old when the Greeks came up with Demeter and Persephone (or, euphemistically, Kore, "the girl" -- Persephone may not have been her real cult name, either). There are distinct hints that the idea was known to the Sumerians a millennium or so beforehand, although in the story in which it seems to appear, not eating or drinking among the gods may have been bad advice.

It is obscure whether Persephone really had much to do with the changes of seasons, as most books confidently assert -- or at least, *which* change of season.

In the minds of most northern European professors it only stood to reason that her time in the netherworld corresponded to winter. However, a great Swedish (!) classicist, Martin P. Nilsson, pointed out that in most of Greece the dry summer is the dead season, while the winter brings life-giving rain.

This problem also applied to their (mis)understanding of West Asian gods, like Adonis and Attis, whose seasonal cycles (if they existed at all) would have been tied to the local climate.)

A (probably) German response was to claim that this only showed that the Aryans had brought the story with them from northern Europe, when they came to civilize the less advanced Asiatic and Mediterranean populations...... (I say probably German because there was an English crackpot who insisted that the Sumerians were Aryans, and brought civilization with them to Mesopotamia, instead of developing it there.)

We might know about Persephone's seasonal movements for certain, at least for Athenians, but the passage which would settle it, in the only manuscript of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, is damaged.

Ian wrote: " in other words, avoid accepting anything from the fairy-folk, or their local equivalent, let alone the God of the Dead."

Ian wrote: " in other words, avoid accepting anything from the fairy-folk, or their local equivalent, let alone the God of the Dead."Someone should have told Rossetti’s girls when they toured the Goblin Market!

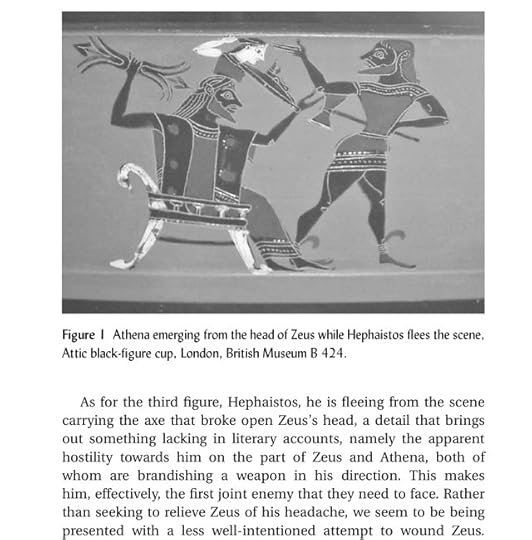

Here’s a painting on an Attic cup depicting “Hephaistos, struck the head of Zeus with an axe and from the top of his head, near the River Triton,* leapt Athene, fully armed.”

Here’s a painting on an Attic cup depicting “Hephaistos, struck the head of Zeus with an axe and from the top of his head, near the River Triton,* leapt Athene, fully armed.”

As noted in the paragraph below, the literary fragments we do have (including Apollodorus) don’t seem to explain why Athena and Zeus seemed hostile to their “midwife.”

Mike wrote: "Where did the company of soldiers called the Kouretes who guarded the baby Zeus come from?"

Mike wrote: "Where did the company of soldiers called the Kouretes who guarded the baby Zeus come from?"Excellent question, for which there is no clear answer. The Kouretes had a role in a mystery-cult (or two), and their story was presumably known to initiates, and only initiates.

As Frazer points out, the clashing of shields and weapons to make noise is a known device for running off demons, and may have been applied to the care of the baby Zeus as a sort of domestic touch, as well as furthering the plot by baffling Kronos. So their function as soldiers, if any, is secondary.

My guess is that the Kouretes ("the lads") belong among the lesser, but still supernatural, beings who came into existence along with the major Titans, and in some cases may be their children: as distinguished from the Olympian gods, who are originally the sons and daughters only of Kronos and Rhea. This might also apply to the nymphs who care for Zeus to begin with, who may, or may not, be sea-nymphs, the daughters of Okeanos, as Hesiod might have categorized them, or other mountain- or tree-nymphs of uncertain, presumably other Titanic parentage.

However, if they are *ash-tree* nymphs, or Meliae, according to Hesiod they arose from the drops of blood of the castrated Ouranos which fell on the Earth. In which case, they sort of have an inherited grudge against Kronos. This view was taken by the Hellenistic poet Callimachus, but where he got the idea is unknown: he was immensely learned, and may have found it in early literature, now lost: but he could have made it up as a logical conclusion.

Lia wrote: "Here’s a painting on an Attic cup depicting “Hephaistos, struck the head of Zeus with an axe and from the top of his head, near the River Triton,* leapt Athene, fully armed.”

Lia wrote: "Here’s a painting on an Attic cup depicting “Hephaistos, struck the head of Zeus with an axe and from the top of his head, near the River Triton,* leapt Athene, fully armed.” As noted in th..."

There is a rival tradition that Prometheus, not Hephaistos, was responsible. This puts Athena's birth very early, as implied by the whole story of the marriage to Metis. And it may take into account the story that Hera produced Hephaistos alone, without a contribution from Zeus, because she was upset about the "birth" of Athena. In which case, he wouldn't yet be around to use the axe!

A similar story is told of Ares, the war-god, which would explain why Zeus in the Iliad explicitly hates him, but this does not seem to have been a popular idea.

I'm not sure whether Zeus is being threatening, or just displaying his attribute (the thunderbolt), but Athena is sometimes regarded as frightening -- and, indeed, any god not yet incorporated into the Olympian system might be so regarded. Apollo's entrance into Olympus in one of the Homeric Hymns frightens the other Gods (although this may not be their introduction to him), and he has to be disarmed and told to sit down by his mother, Leto.

I assume the asterisk was for a note explaining that the specific locale is offered to explain Athena's mysterious epithet "Tritogeneia," which seems to mean something like "born of Triton," which makes no sense in terms of the rest of her mythology.

Ian wrote: "Athena is sometimes regarded as frightening -- and, indeed, any god not yet incorporated into the Olympian system might be so regarded. Apollo's entrance into Olympus in one of the Homeric Hymns frightens the other Gods (although this may not be their introduction to him), and he has to be disarmed and told to sit down by his mother, Leto."

Ian wrote: "Athena is sometimes regarded as frightening -- and, indeed, any god not yet incorporated into the Olympian system might be so regarded. Apollo's entrance into Olympus in one of the Homeric Hymns frightens the other Gods (although this may not be their introduction to him), and he has to be disarmed and told to sit down by his mother, Leto."While that’s true, Athena’s birth was also depicted as shockingly scary in the Homeric Hymns:

“ I sing of the glorious goddess Pallas Athena,

owl-eyed deity with crafty wisdom and steady heart,

revered virgin, stalwart guardian of the city,

Tritogeneia. From his august head, cunning Zeus

himself gave birth to her, born in warlike armor

of gleaming gold. Awe seized all the gods watching.

She sprang quickly from his immortal head

and stood in front of Zeus who bears the aegis,

shaking her sharp spear. Great Olympos reeled

violently beneath the might of her shining eyes, 10

the earth let out an awful cry, and the deep shifted,

churning with purple waves. Suddenly the sea

held still and the shining son of Hyperion halted

his swift horses a long while until the maiden

Pallas Athena lifted the godlike armor

from her divine shoulders, and wise Zeus rejoiced.

Hail, child of aegis-bearing Zeus—

but I will remember you and the rest of the song. ”

It was so shocking the Sun stopped! It seems bold of Apollodorus to leave all that out, I hope he’s got good insurance coverage (that covers “act of god”. We know what happens to those who cross Athena.

I’m still on Athena’s case. This is somewhat related to Dave’s post about god's contending against each other: if, as Ian suggested, Athena and Zeus’s hostility to the midwife signals rivalry between Hera’s descendant vs Zeus’s descendant (and the Iliad is basically a big cluster-fork between descendants of various gods)

I’m still on Athena’s case. This is somewhat related to Dave’s post about god's contending against each other: if, as Ian suggested, Athena and Zeus’s hostility to the midwife signals rivalry between Hera’s descendant vs Zeus’s descendant (and the Iliad is basically a big cluster-fork between descendants of various gods)Ian wrote: “There is a rival tradition that Prometheus, not Hephaistos, was responsible. This puts Athena's birth very early, as implied by the whole story of the marriage to Metis. And it may take into account the story that Hera produced Hephaistos alone, without a contribution from Zeus, because she was upset about the "birth" of Athena. In which case, he wouldn't yet be around to use the axe!

A similar story is told of Ares, the war-god, which would explain why Zeus in the Iliad explicitly hates him, but this does not seem to have been a popular idea.”

That makes Athena’s ambiguity (violently threatening and city-protecting/ order-restoring) very significant in the divine-succession scheme! Zeus swallowed Metis to foil the stronger-son prophesy, (just like Zeus forced Thetis to mate with Peleus to foil yet another stronger-son prophesy) and Athena is the manifestation, the method, the means of defeating the challenger. From the moment of birth she’s shown (in that painting) to go after those whom would threaten Zeus’ hegemony. Zeus replaced one wise Goddess (Metis) with a wise-but-loyal-to-status-quo anti-rebel wisdom-Goddess (Athena). He foiled the prophesy by birthing a daughter (who behaves like a boy) instead of a son. I think, merely mentioning “she popped out of his forehead at the Trident” takes out all that divine-succession drama that Athena’s birth is entangled in.

I was in a hurry yesterday, and somewhat garbled my report on Hittite mythological texts. I should have said that the "Kumarbi Cycle" is still so named, while "The Song of Release" is a newly (1983-1985) discovered text.

I was in a hurry yesterday, and somewhat garbled my report on Hittite mythological texts. I should have said that the "Kumarbi Cycle" is still so named, while "The Song of Release" is a newly (1983-1985) discovered text.However, I've located on-line sources for the some of the Hittite material relevant to the "Theogony" (and the digest in Apollodorus) which appears in "Gods, Heroes, and Monsters," as edited and translated by Mary Bacharovna. I've included a supplementary article to which she called special attention.

revision of translation: "Kumarbi Cycle," in Gods, Heroes, and Monsters: A Sourcebook of Greek, Roman, and Near Eastern Myths in Translation (2017), ed. C. López-Ruiz. 2nd ed. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.154-76, by Mary Bacharovna

https://www.academia.edu/39143206/rev..."

Unfortunately, this cuts off the last page.

For an explanation of the revisions, see Mary Bacharovna, "Multiformity in the Song of Hedammu"

from Altorientalische Forschungen 45,1-21, 2018

https://www.academia.edu/39143038/Mul...

Her abstract is: "The narrative tradition of the Hurro-Hittite Song of Ḫedammu is presented, arguing that two separate Hittite versions can be reconstructed, one relatively condensed, the other more prolix. Such multiformity supports the postulation of an oral tradition lying behind the scribal production of Hurro-Hittite narrative song at Ḫattuša."

(This analysis suggests connections to the Homeric and Hesiodic epics: concerning which Bacharovna has written "From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016)

and

Translation of Song of Release, from Gods, Heroes, and Monsters: A Sourcebook of Greek, Roman, and Near Eastern Myths in Translation, 2nd ed. (2017), edited by Carolina López-Ruiz. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2013)

by Mary Bachvarova

https://www.academia.edu/4668136/Tran...

Unfortunately, she has not posted her translation there of the Iluyankas myths, concerning the Storm-God's struggles with a giant serpent (the name may mean something like "Mr. Snake"), one of which has a parallel to an otherwise unique detail in Apollodorus.

Cphe wrote: "It’s all about power.......some things never change."

Cphe wrote: "It’s all about power.......some things never change."This comment, and your previous comment about expecting myths to be romantic, really makes me wonder if Ovid is to blame, in that he wedded martial epics with sexual conquest.

It seems Olympian sex (procreation) is frequently about power, about politics, succession, honor (i.e. having victorious hero sons). That unlikely pairing of sexual union and force has always been there (see Ares and Aphrodites in exhibit-A), but Ovid blurred the boundary even more by depicting sexual conquests in a form primarily reserved for tales of wars or martial triumphs.

Now that you mention it, yes, it is apparent that Olympian sex is about power relationships, usually gravely unbalanced ones.

Now that you mention it, yes, it is apparent that Olympian sex is about power relationships, usually gravely unbalanced ones.This attitude certainly was not confined to myths, but was probably a spillover from everyday life into the lives of the gods. And the Greeks recognized it, at least in certain contexts.

Greek "Love Magic" usually consisted of (theoretically) employing some sort of force against the desired object (usually regarded as an object) -- sometimes, as in Sappho, cloaked in an appeal for divine intervention, often explicitly malicious. For this issue with specific examples, including echoes in other poets (such as a new reading of a piece about a Thracian girl by Anacreon), see Christopher Faraone's Ancient Greek Love Magic.

This book used to be available from academia.edu, but it is no longer posted there. I have found an alternative source for a download: https://www.pdfdrive.com/ancient-gree... This does not seem to require creating an account, but it does offer premium services for a fee, and you may not want to use it. (Firefox failed to flag it as dangerous, but that is not a guarantee that it is legitimate.)

There is a great deal of other, related, material by Faraone which is available from academia.edu: see his page there, http://chicago.academia.edu/Christoph...

Additional note: I should have mentioned that the latest papers (forthcoming 2020 through 2021)by Faraone have not been uploaded. I downloaded some of the rest some time ago, but I'm not sure if all of them are still available there.

Ian wrote: "Greek "Love Magic" usually consisted of (theoretically) employing some sort of force against the desired object (usually regarded as an object)..."

Ian wrote: "Greek "Love Magic" usually consisted of (theoretically) employing some sort of force against the desired object (usually regarded as an object)..."And then sometimes, they turn desired/desiring subjects (people) into objects. (Rocks, stags, trees, rivers...)

No. I though of the legendary Dead Sea Apples, which were beautiful on the outside, but ashes within.

No. I though of the legendary Dead Sea Apples, which were beautiful on the outside, but ashes within.Frazer says (note 99 to Book I) "This story of the deception practised by the Fates on Typhon seems to be otherwise unknown." So far as I know, nothing has turned up since that would cast any light on it.

The intervention of Hermes and Aigipan (who may or may not be the god Pan, son of Hermes: the redundant-sounding "Goat-Pan" just might have designated some other, primeval, deity) is in line with Hermes' role as a thief. For example, In another story about enemies of the Olympians, he similarly rescues Ares, who has been shut up in a great bronze jar by brother Giants.

The intervention of Hermes and Aigipan (who may or may not be the god Pan, son of Hermes: the redundant-sounding "Goat-Pan" just might have designated some other, primeval, deity) is in line with Hermes' role as a thief. For example, In another story about enemies of the Olympians, he similarly rescues Ares, who has been shut up in a great bronze jar by brother Giants.In note 98, Frazer reports that: "According to Nonnus, Dionys. i.481ff., it was Cadmus who, disguised as a shepherd, wheedled the severed sinews of Zeus out of Typhon by pretending that he wanted them for the strings of a lyre, on which he would play ravishing music to the monster. The barbarous and evidently very ancient story seems to be alluded to by no other Greek writers."

(Nonnus was the author of an epic poem on the career of Dionysus, the Dionysiaca, which is not well-thought-of by most classicists, although it displayed considerable antiquarian learning. If the same man is meant by the name, Nonnus was also a bishop....)

Frazer does not explicitly note that the involvement of Cadmus would place the Typhon story well into the Heroic Age, which for the Greeks immediately preceded recorded history, and was quite separate from the primeval times in which such earth-moving divine combats with giant monsters might be expected. Apollodorus, with only gods involved, can't be pinned down like that.

Frazer was of course not aware of a yet-to-be-discovered Hittite text which offers another partial parallel. There are two versions (in the same composition) of the story of the Storm-God's struggle with Illuyankas, or "The Serpent" (also rendered Illuyanka in English).

In the second version Illuyankas carries off the heart and eyes of the Storm-God, which more than inconveniences him. The Storm-God (as in the other version) resorts to trickery. In this case, he begets a mortal son, who arranges to marry the daughter of Illuyankas (who seems in this passage to be at least somewhat anthropomorphic).

After continued exhortation from the Storm-God, the new husband asks his father-in-law for the heart and eyes, and, when he gets them, returns them to his father, who then attacks and defeats Illuyankas. All would seem to end happily, except that the Storm-God's son insists on dying with his new family, for reasons not explained, but perhaps involving guilt over divided loyalties.

This is just close enough to the Greek versions to suggest that the concept passed over into Greek tradition from Asia Minor. It seems to have been separate from the Kumarbi Cycle, in which the Storm-God, with his allies, defeats or tricks a series of enemies. The Greek stories of Typhoeus/ Typhon/Typhaon (various forms in use) seem to have been assimilated to the plot of the Hesiodic Theogony, with its own resemblances to Hittite (or Hurrian-Hittite) literature.

I don’t have any particular insights to share yet, though I am interested in examining the myths for meaning/symbolism and plan to post some specific questions once I gather my thoughts. So far, I feel like I’m reading the notes of a lecture from Ian; not that I’m complaining as I find it interesting, but I hope we can discuss the metaphors involved and competing interpretations of meaning as well as detail.

I don’t have any particular insights to share yet, though I am interested in examining the myths for meaning/symbolism and plan to post some specific questions once I gather my thoughts. So far, I feel like I’m reading the notes of a lecture from Ian; not that I’m complaining as I find it interesting, but I hope we can discuss the metaphors involved and competing interpretations of meaning as well as detail.To that end, I just wanted to mention a trend I’m seeing in early posts to figure out which version of various myths is “right.” I think it’s important to remember as we progress that while the Library is a reference work, there was no “primary source” it drew from or to refer to for accuracy.

Something I’ve loved about studying Ancient Greek literature this year is that while the overall myths are constant (and often actually follow familiar motifs from earlier cultures’ mythology/literature), each work is itself an interpretation of what was passed down to that author through the oral tradition and previous poetic works they were exposed to. Some works followed the oldest written versions by Hesiod and Homer and some forged their own alternative, but each author left his interpretative mark on the canon.

All this to say that I love to hear about the different versions, but I’d be even happier to hear about whether you think the detail changes are meaningful or incidental? And if meaningful, what do they mean?

That’s not a question addressed to anyone. Just weighing in with my initial framing thoughts.

Aiden wrote: “ Some works followed the oldest written versions by Hesiod and Homer and some forged their own alternative, ”

Aiden wrote: “ Some works followed the oldest written versions by Hesiod and Homer and some forged their own alternative, ” There’s a third choice: they all (including Homer and Hesiod) drew on the same mythological tradition, and the younger accounts drew on common mythographic sources that are now lost to us. Let me quote Epic Cycle scholar Jonathan Burgess as an example of what I mean:

“ If the tradition of the Trojan War were a tree, initially the Iliad and Odyssey would have been a couple of small branches, whereas the Cycle poems would be somewhere in the trunk... too often scholars seek to prove their love of the Homeric poems by ignoring or denigrating the traditions behind them. The tradition of the Trojan War had a long and complex development before the Homeric poems were composed. Indo-European concepts may lie embedded within the story, and Near Eastern influences also undoubtedly had an effect...“

“ I repeatedly stress that the influence of the Iliad and Odyssey on their mythological tradition was not great in the Archaic Age, although this is routinely assumed. Whether individual or tradition, Homer has been overemphasized at the risk of losing sight of the larger mythological tradition. Scholars who fancy the individual poet of genius tend to argue that his inventiveness and sophistication instantly outdated the preexisting tradition and overshadowed attempts to continue this tradition...Two consequences follow: no pure representative of the pre-Homeric tradition becomes possible once Homer has muddied the waters, and any use of the preexisting tradition by the Homeric poems becomes obscure because of the very success of the Homeric poems. Such exaggeration of the early influence of the Homeric poems necessarily devalues the Epic Cycle.”

“ But on the whole it seems that the Trojan War poems of the Epic Cycle well represent the traditional story of the Trojan War. The artistic evidence implies that at least some themes in the Epic Cycle are independent of the Homeric poems and based on a tradition that preceded and survived them. No scholar has been able to explain away this evidence.”

Also, marginally relevant:

“(Scodel) ‘The discussion of the Cycle has too often been framed in terms based on written texts, where we expect a sequel or introduction to fit itself precisely to the text that precedes it. This is not the standard we should apply to early Greek epic. The general shape of these poems gives the impression that they were composed with a view to telling a single story, but that the poets did not recognize the versions of others as possessed of any absolute authority. I would suggest that we understand the ‘cyclic impulse’ as a basic (though not, of course, universal) characteristic of archaic epic.’”

What I’m trying to suggest is, they might not be seeing themselves as putting a spin on or “forging alternatives” to what’s traditional and dominant or canonical. They were creating within the same tradition, Homer (and maybe Hesiod) became overemphasized for generations and we now tend to view them as canonical when canonicity wasn’t in their habit of thoughts. Perhaps, each poet or mythographer or dramatist had just as much license to draw on their own tradition, while expressing whatever their milieu was concerned with.

Aiden wrote: "I don’t have any particular insights to share yet, though I am interested in examining the myths for meaning/symbolism and plan to post some specific questions once I gather my thoughts. So far, I ..."

Aiden wrote: "I don’t have any particular insights to share yet, though I am interested in examining the myths for meaning/symbolism and plan to post some specific questions once I gather my thoughts. So far, I ..."I suppose my posts do sound like lecture notes -- probably from a lecture I would have liked to have heard in the 1970s, when I finally was able to take a UCLA course in classical mythology (which, as I think I mentioned earlier, maybe in the lead-up to this discussion, was not offered very frequently, and in previous years had conflicted with required courses in my major).

I found that, from my position of having already read a lot of the basic literature (Homer, Hesiod, Ovid), it was on a fairly elementary level. Not to blame anyone, it was aimed at undergraduates not taking Classical Studies, and basic information (like who was Zeus) was prioritized. And I agreed with the professor that the attractive, highly-recommended, new textbook we used was in practice rather disappointing, so that he had to go over some things in class that we should have picked up from reading it.* (Although I think he was stretching the point when he compared the chapter on the Mysteries of Eleusis to an undergraduate paper.)

Whereas that really informative graduate course in Comparative Mythology took for granted that you knew the Greco-Roman material already.....

Unfortunately, if you are waiting for metaphors and deep insights, Apollodorus is not going to provide many of them. For that, we would have to go to Hesiod, the tragedians, and Ovid. "The Library" offers us a bare-bones approach, and would be entirely negligible if additional literary sources, including the Epic Cycle, and some of the works attributed to Hesiod, had survived. But they didn't.

But they didn't, and "The Library" is the only source (or only coherent source) for a great deal of Greek mythology, one which treats it as a somewhat coherent body of material, and not a random collection of sometimes interesting stories, as in the much-reworked "Fabulae," in Latin, passing under the name of Hyginus, which is coupled with Apollodorus in another translation.

Or the sometimes dubiously authentic constellation myths of (Pseudo-)Eratosthenes, Hyginus (again), and Aratus -- which three I mention specifically because they were also translated by Robin Hard, in a companion volume to the "Library" in the Oxford World's Classics.

*It was the first edition of Morford and Lenardon's Classical Mythology, now in its eleventh, and absurdly overpriced, edition (not shown on Goodreads: see https://www.amazon.com/Classical-Myth...) I assume that it was considerably improved over the years.....

Ian wrote: "Unfortunately, if you are waiting for metaphors and deep insights, Apollodorus is not going to provide many of them."

Ian wrote: "Unfortunately, if you are waiting for metaphors and deep insights, Apollodorus is not going to provide many of them."It wasn’t Apollodorus’ text that I was looking to for the metaphors and deep insights; it’s from this very well-read discussion group, some of whom have read widely in classical literature. I thought some might be interested in the heavy lifting of analyzing the differences in important details between Apollodorus’ dry reference work and other primary sources (in the case of Book 1, this would mostly be Hesiod’s epic, Theogeny, the Homeric Hymns and the hymns of Callimachus).

Aiden wrote: "It wasn’t Apollodorus’ text that I was looking to for the metaphors and deep insights; it’s from this very well-read discussion group, some of whom have read widely in classical literature..."

Aiden wrote: "It wasn’t Apollodorus’ text that I was looking to for the metaphors and deep insights; it’s from this very well-read discussion group, some of whom have read widely in classical literature..."In light of Aiden's comment, I'd like to suggest a different reading of the Persephone story.

At the risk of blowing my own horn, my first book, Demeter and Persephone: Lessons from a Myth, is a feminist interpretation of the Demeter/Persephone myth based on Helen Foley's translation of The Homeric Hymn to Demeter: Translation, Commentary and Interpretive Essays.

According to the translation, we are told that Hades explains to Persephone the extent of her powers as queen of the underworld. He does so just before she exits. He also suggests she can retain those powers only if she makes periodic returns to the underworld. And in order to do that, she has to swallow the food of the underworld. Foley translates Persephone's reaction:

Thus he spoke and thoughtful Persephone rejoiced.

Eagerly she leapt for joy. But he gave her to eat

A honey-sweet pomegranate . . .

Why does Persephone rejoice? Why does she leap for joy? And why does she swallow the pomegranate seed when she could have spit it out? I argue she swallows it because she wants to go back. She wants to retain her power by straddling the two realms of the upper world and underworld. She exercises choice. As Hades tells her,

. . . you will have power over all that lives and moves,

and you will possess the greatest honors among the gods

The question was asked in an earlier post why pomegranate seeds. The abundance of seeds in a pomegranate make it an obvious symbol of fertility. Medieval paintings frequently depict the Virgin Mary as holding a pomegranate. Also, a lot can be made of the color red with its associations with birth, death, and menstrual flow.

By swallowing the pomegranate seed on her way out of the chthonic realm, Persephone carries with her the seeds of fertility to the surface of the earth. She precipitates new life. And she embodies new life since she "dies" in the underworld and is re-born when she surfaces.

Bruce Lincoln in Emerging from the Chrysalis: Rituals of Women's Initiation claims there are also male associations with the word "seed." The term used in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter is kokkos. Kokkos not only means seed; it can also signify "testicle." I don't speak Greek so I don't know if that is accurate. However, one can see the connection since both [pomegranate and testicle] are round, bulbous, and contain a prodigious number of seeds.

I'll leave you with that thought :)

Aiden wrote: "Ian wrote: "Unfortunately, if you are waiting for metaphors and deep insights, Apollodorus is not going to provide many of them."

Aiden wrote: "Ian wrote: "Unfortunately, if you are waiting for metaphors and deep insights, Apollodorus is not going to provide many of them."It wasn’t Apollodorus’ text that I was looking to for the metaphor..."

I'm not sure if we should be flattered by this expectation. I, for one, don't have the memory for that fine a level of detail: differing plot-points are more likely to stick in my mind.

J.G. Frazer catalogued almost the whole of the relevant Greek and Latin literature in his translation of Apollodorus (there have been relatively minor discoveries since), and this is available in a very nice, very inexpensive, Delphi Classics Kindle edition (and some other formats). I could probably crib from there, instead of just occasionally noting some of Frazer's explanations (whether or not I agree with them).

But I think having pointed the book out in the Backgrounds and Translations thread was a lot more efficient, and likely to be less tedious.

And, for this discussion I'm not prepared to search my copies of Pindar translations to see if translators even agree on what his (highly poetic) language means, before inflicting it on others as revealing something about the story. The surviving poems, celebrations of athletic victories in the major Greek Games, are extremely difficult, and very allusive. (Although what he demonstrates about the contexts in which they were sometimes retold is interesting, and I may bring him up when we get to the heroic mythology he cites in the "Odes.") Or as supporting or contradicting Frazer's usually well-informed understanding of the Greek.)

We've been dealing with the Homeric Hymns a bit, but their flood of information often seemed overkill, even for me. (We might do a separate discussion for them: there are a number of recent, very good, translations -- and a couple I'm not so happy about.)

I could have pulled out the great Hymn to Apollo in describing his oracles -- but I didn't want to deal with the question of whether it is really one hymn, or two run together (Delian and Delphic), or one hymn and a deliberate sequel to supplant the message of the first: all of which might have useful for the parallel to the possible rivalry of Dodona and Delphi, which I mentioned mainly as a quick example of another Olympian having an oracle.

As a general rule, when a classical (or late antique) writer "explains" a myth, it involves painfully obvious re-statements of the obvious under the name of allegory, exceedingly unlikely "meanings" using the same tools, or transparent rationalizations.

So Atlas doesn't hold up the sky, but was a famous astronomer. Another such "explanation" which comes to mind immediately concerns the story of Herakles bringing Cerberus, the hell-hound, to Eurystheus as one of his Twelve Labors.

The elucidation is that Cerberus was not a three-headed watchdog preventing escape from the Netherworld, but a very large snake whose bite was so lethal that it was also known as "the Hound of Hades." And so, with on with the rest of his adventures. In the one book the historical "Library" of Diodorus Siculus devoted to the early Greek past, the mythical hero winds up as a combination of an animal-control officer, Alexander the Great, and a whole gang of Roman engineers.

Ian, I didn’t mean it as a criticism at all. Your level of commentary is something I value highly. I just knew that we have different members with different backgrounds and wanted to invite the more poetic commentary as well.

Ian, I didn’t mean it as a criticism at all. Your level of commentary is something I value highly. I just knew that we have different members with different backgrounds and wanted to invite the more poetic commentary as well. Tamara, thank you for proving I was right and please feel free to keep it coming. I find literary dialogue at this level invaluable to my growth as a writer and hopefully others will find it enlightening as well. The modern interpretation is compelling and gives me food for thought.

The cultic appellation of Kore (“the Maid”) always seemed somewhat strange to me for the queen of the underworld. It’s true that Persephone is portrayed as a damsel captured and tricked by Hades, but it seemed to me that she took charge once she was queen. She is respected and feared below and worshipped and loved above. Your interpretation opens the idea that maybe she was always in control, or at least turned her circumstances to her advantage with relish.

I am wondering if these wars, especially between the giants, Typhon, and the Olympians were there to explain the origins of volcanoes and mountains, etc., or were they more psychological in origin? Could they be considered as later generations being punished by the, mistakes, sins, ill-will, or just revenge, of the earlier generations?

I am wondering if these wars, especially between the giants, Typhon, and the Olympians were there to explain the origins of volcanoes and mountains, etc., or were they more psychological in origin? Could they be considered as later generations being punished by the, mistakes, sins, ill-will, or just revenge, of the earlier generations?I don't think I ever heard of Typhon taking Zeus' tendons before. Why his tendons? Or are tendon's just a well known weak spot, even for personalities like Zeus and Achilles?

Tamara wrote: "Aiden wrote: "It wasn’t Apollodorus’ text that I was looking to for the metaphors and deep insights; it’s from this very well-read discussion group, some of whom have read widely in classical liter..."

Tamara wrote: "Aiden wrote: "It wasn’t Apollodorus’ text that I was looking to for the metaphors and deep insights; it’s from this very well-read discussion group, some of whom have read widely in classical liter..."A pomegranate seed is also the smallest possible bit of food--eating it is a small innocent act leading to immense consequences.

Having brought up both the Homeric Hymn to Apollo and Hera's parthenogenetic birth of Hephaeustus, I should mention that the second part of the Hymn includes as a flash-back Hera's anger over the "birth" of Athena, her (apparently prior) disappointment with Hephaestus, and, in an unusual touch, her giving birth to Typhaon (= Typhon) in the same way, as a form of revenge on Zeus -- and all the other Olympians, and anyone else who gets in the monster's way. (One can sympathize with Hera over Zeus' philandering, but she tends to persecute the weak and innocent: and now, when she finally takes on Zeus more directly she doesn't care who else gets hurts.)

Having brought up both the Homeric Hymn to Apollo and Hera's parthenogenetic birth of Hephaeustus, I should mention that the second part of the Hymn includes as a flash-back Hera's anger over the "birth" of Athena, her (apparently prior) disappointment with Hephaestus, and, in an unusual touch, her giving birth to Typhaon (= Typhon) in the same way, as a form of revenge on Zeus -- and all the other Olympians, and anyone else who gets in the monster's way. (One can sympathize with Hera over Zeus' philandering, but she tends to persecute the weak and innocent: and now, when she finally takes on Zeus more directly she doesn't care who else gets hurts.)I'll quote the 1899 prose translation of Andrew Lang, in the version modernized in "The Anthology of Classical Myth,"second edition, ed. Stephen M. Trzaskoma, R. Scott Smith, and Stephen Brunet, where some of the names have been restored to Greek from Lang's English (e.g., "Earth" and "Heaven"). (But they kept his "Cronides" for Zeus, which some modern translators render transparently as "Son of Kronos.")

The young Apollo has just reached the site of his future oracle at Delphi, and discovered that it is occupied by a very large venomous female snake, a drakona, often rendered as "dragon" (Lang's original), or "dragoness."

The implied etymology of the English is correct, but the creature unlike Smaug, or the transformed Maleficent in Disney's "Sleeping Beauty," lacks wings or fiery breath. Nor does she have the cunning and magical power of Glaurung in the "Silmarillion." But she is formidable enough to cast Apollo as savior when he shoots her with his arrows.

(lines 307-352) It was this dragoness that took from golden-throned Hera and reared the dread Typhaon, not to be dealt with, a bane to mortals. Hera bore him, once upon a time, in wrath with father Zeus at the time when Cronides brought forth from his head renowned Athena. Straightway lady Hera was angered and spoke among the assembled gods:

"Listen to me, you gods and goddesses all, how cloud-gathering Zeus is first to begin the dishonoring of me, though he made me his wife in honor. And now, apart from me, he has brought forth gray-eyed Athena who excels among all the blessed immortals. But my son Hephaistos was feeble from birth among all the gods, lame and withered of foot, whom I myself bore. Him I myself lifted in my hands and cast into the wide sea. But the daughter of Nereus, Thetis of the silver feet, received him and nurtured him among her sisters. Would that she had done some other grace to the blessed immortals! You evil one of many wiles, what other wile are you devising? How did you have the heart now alone to bear gray-eyed Athena? Could I not have borne her? She still would have been called yours among the immortals who hold the wide heaven. Take heed now that I do not devise for you some evil to come. Yes, now I shall use arts whereby a child of mine shall be born, excelling among the immortal gods, without dishonoring your sacred bed or mine, for in truth to your bed I will not come, but far from you will I nurse my grudge against the immortal gods."

So spoke she and withdrew from the gods with angered heart. Immediately she made her prayer, the ox-eyed lady Hera, striking the earth with her palms, and spoke her word:

"Listen to me now, Gaia, and wide Ouranos above, and you gods called Titans, dwelling beneath earth in great Tartaros, you from whom spring gods and men! Listen to me now, all of you, and give me a child apart from Zeus, yet nothing inferior to him in might, no, stronger than he, as much as far-seeing Zeus is mightier than Cronos!"

So spoke she and struck the ground with her firm hand. Then Gaia, the nurse of life, was stirred, and Hera, beholding it, was glad at heart, for she deemed that her prayer would be accomplished. From that hour for a full year she never came to the bed of wise Zeus, nor to her adorned throne, where she used to sit, planning deep counsel. But dwelling in her prayer-filled temples, she took joy in her sacrifices, the ox-eyed lady Hera. Now when her months and days were fulfilled, the year revolving and the seasons in their course coming round, she bore a birth like neither gods nor mortals, the dread Typhaon, not to be dealt with, a bane of gods. Him now she took, the ox-eyed lady Hera, and carried and gave one evil to another, and the dragoness received him. The dragoness always wrought many wrongs among the renowned tribes of men.

The raising of Typhaon by the Drakona is glossed over in a couple of lines, without details, so we quickly get back to Apollo's "cleansing" Delphi.

that is an interesting twist to the Typhon story here with Ge/Gia granting the birth of Typhon to Hera instead of giving birth to him herself.:

that is an interesting twist to the Typhon story here with Ge/Gia granting the birth of Typhon to Hera instead of giving birth to him herself.:When the gods had defeated the Giants, Ge, whose anger was all the greater, had intercourse with Tartaros and gave birth to Typhon.Hera is a most interesting character. She is both utterly terrifying to the innocent and completely ineffectual in bringing about the changes she wants in Zeus. She is not without some justification for her motives, but the words capricious, jealous, temperamental, unreasonable and causing only collateral damage most often come to mind.

With a note on Typhon: Hesiod offers a rather different account of his struggle with Zeus, in Theog. 820 ff.

One of the most interesting things for me about that passage was the concept of a god praying to other gods (in this case primordial powers).

One of the most interesting things for me about that passage was the concept of a god praying to other gods (in this case primordial powers).So far as I can recall, we don't hear of the gods going so far as offering sacrifices -- except in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, in which the baby god makes offerings to the canonical Twelve Olympians, himself very much included, as a way of claiming divine status along with the other eleven.

(There is a rabbinic claim that the LORD himself prays daily: what could he say? He says "may this day My attribute of Mercy be able to overcome My attribute of Strict Justice." [Paraphrased: I've long since lost track of the source.]

(As to the contents of the "prayer," another Rabbinic saying [ditto] was that God first created a universe governed only by Mercy, and its creatures destroyed it. He created another governed only by Strict Justice, and He had to destroy it Himself. Then He made our world, which is governed by both, and so far He has sustained it.)