The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Bleak House

>

Bleak House Chapters 8-10

Chapter 9

Signs and Tokens

In this chapter we will find a blooming romance, a botched attempt at a proposal for marriage, and meet a new character who is connected in some way to both Chesney Wold and Mr Jarndyce. In this novel I feel like I’m watching a spider create a web. Slowly, but surely, Dickens is joining seemingly unconnected elements of plot, character, and narrative into a web of connections.

This is another chapter with Esther as our narrator. Once again, her tone is one of self-effacement. She sees herself as a “tiresome little creature.” We learn that Esther and Ada spend much time together at Bleak House and that Richard is a rather restless character who, while not exactly like Mr Micawber, is a person who needs to have more control over his finances. The only consistent aspect of Richard’s character is that he is “very, very, very fond” of Ada. We read that Mr Jarndyce has contacted Sir Leicester Dedlock for his aid in finding Richard a career as a sailor. We are reminded by Esther that the Dedlock’s are connected to Richard by a “remote consanguinity.” At this point in time we need to remember that Esther has no idea who the Dedlock’s are.

Esther’s knowledge of the Dedlock’s is soon to change. Mr Jarndyce welcomes an old friend to Bleak House by the name of Lawrence Boythorn. Boythorn is a very tall and boisterous man who has a warm heart and enjoys being in conflict with his neighbour who turns out to be none other than the Dedlock’s. If there is any doubt about Boythorn’s kindness, Dickens provides a grand example of imagery. It turns out that Boythorn has a pet canary and Dickens places this canary either on Boythorn’s head or hand numerous times during the chapter. Now, how can anybody who has a canary be all bad? :-). We also learn that Boythorn once was almost married, but that was long ago.

In the second part of this chapter we are re-introduced to Mr Guppy, a lawyer from Kenge and Carboy’s. Guppy seems to pop up in this novel frequently. The novel Bleak House has been rather devoid of humour so far, but Mr Guppy provides the reader with a few smiles, if not a laugh or two. First, however, let’s pause for a moment. Esther notices that Guppy looks at her with “an attention that quite confused me.” Later she notes that he looks at her again “in the same scrutinizing and curious way.” Guppy becomes very attentive to Esther and asks for a moment of private attention. Guppy falls on his knees and proposes to Esther. Good grief!

Esther is horrified and tells Guppy to leave, but Guppy insists on telling Esther of his modest salary, his mother, and his home. Esther remains unimpressed. Finally, Guppy gives up on his proposal to Esther, and asks her to promise not to broadcast his rejection. As if poor Esther would. I imagine she just wanted him out the door ASAP. Guppy leaves, but Esther once again remarks how she noticed Guppy looking at her. The chapter ends with Esther first laughing at her afternoon with Guppy and then crying at its remembrance. Esther then reflects on the fact that she has never “been more coarsely touched ... since the days of the dear old doll, long buried in the garden.” For those who were waiting for any further reference to Esther and her buried doll, here it is. What does it all mean?

Reflections

At last Dickens has given his readers a good healthy scene of laughter. I think we needed it. To what extent did you find humour in the introduction of Boythorn as well?

Is love in the air? Ada and Richard are obviously in love with one another, we are told that Boythorn was was in love but never married, and we ended the chapter with the bumbling proposal of Guppy. What might be the significance of such a concentrated focus on love in this chapter?

Once again, we have Chesney Wold hovering in the background of this chapter. We also have the mention of a connection between the characters who live at Chesney Wold and Bleak House? Any speculations yet?

Esther frequently mentions that Guppy spends a great amount of time looking at Esther. Is it merely love?

Signs and Tokens

In this chapter we will find a blooming romance, a botched attempt at a proposal for marriage, and meet a new character who is connected in some way to both Chesney Wold and Mr Jarndyce. In this novel I feel like I’m watching a spider create a web. Slowly, but surely, Dickens is joining seemingly unconnected elements of plot, character, and narrative into a web of connections.

This is another chapter with Esther as our narrator. Once again, her tone is one of self-effacement. She sees herself as a “tiresome little creature.” We learn that Esther and Ada spend much time together at Bleak House and that Richard is a rather restless character who, while not exactly like Mr Micawber, is a person who needs to have more control over his finances. The only consistent aspect of Richard’s character is that he is “very, very, very fond” of Ada. We read that Mr Jarndyce has contacted Sir Leicester Dedlock for his aid in finding Richard a career as a sailor. We are reminded by Esther that the Dedlock’s are connected to Richard by a “remote consanguinity.” At this point in time we need to remember that Esther has no idea who the Dedlock’s are.

Esther’s knowledge of the Dedlock’s is soon to change. Mr Jarndyce welcomes an old friend to Bleak House by the name of Lawrence Boythorn. Boythorn is a very tall and boisterous man who has a warm heart and enjoys being in conflict with his neighbour who turns out to be none other than the Dedlock’s. If there is any doubt about Boythorn’s kindness, Dickens provides a grand example of imagery. It turns out that Boythorn has a pet canary and Dickens places this canary either on Boythorn’s head or hand numerous times during the chapter. Now, how can anybody who has a canary be all bad? :-). We also learn that Boythorn once was almost married, but that was long ago.

In the second part of this chapter we are re-introduced to Mr Guppy, a lawyer from Kenge and Carboy’s. Guppy seems to pop up in this novel frequently. The novel Bleak House has been rather devoid of humour so far, but Mr Guppy provides the reader with a few smiles, if not a laugh or two. First, however, let’s pause for a moment. Esther notices that Guppy looks at her with “an attention that quite confused me.” Later she notes that he looks at her again “in the same scrutinizing and curious way.” Guppy becomes very attentive to Esther and asks for a moment of private attention. Guppy falls on his knees and proposes to Esther. Good grief!

Esther is horrified and tells Guppy to leave, but Guppy insists on telling Esther of his modest salary, his mother, and his home. Esther remains unimpressed. Finally, Guppy gives up on his proposal to Esther, and asks her to promise not to broadcast his rejection. As if poor Esther would. I imagine she just wanted him out the door ASAP. Guppy leaves, but Esther once again remarks how she noticed Guppy looking at her. The chapter ends with Esther first laughing at her afternoon with Guppy and then crying at its remembrance. Esther then reflects on the fact that she has never “been more coarsely touched ... since the days of the dear old doll, long buried in the garden.” For those who were waiting for any further reference to Esther and her buried doll, here it is. What does it all mean?

Reflections

At last Dickens has given his readers a good healthy scene of laughter. I think we needed it. To what extent did you find humour in the introduction of Boythorn as well?

Is love in the air? Ada and Richard are obviously in love with one another, we are told that Boythorn was was in love but never married, and we ended the chapter with the bumbling proposal of Guppy. What might be the significance of such a concentrated focus on love in this chapter?

Once again, we have Chesney Wold hovering in the background of this chapter. We also have the mention of a connection between the characters who live at Chesney Wold and Bleak House? Any speculations yet?

Esther frequently mentions that Guppy spends a great amount of time looking at Esther. Is it merely love?

Chapter 10

The Law-Writer

In this chapter we continue to slide deeper into the mystery of who was the writer of the document that so interested Lady Dedlock. That means we will spend some more time with Mr Tulkinghorn as well. Fist, however, we meet a couple of new characters and spend some time in a new location.

As a contrast to Krook and his rag shop of disused paper, we begin the chapter by meeting Mr Snagsby. He operates a stationary store that deals with all sorts of clean paper and forms concerning the legal process. I imagine a 19C equivalent of a Staples outlet. There is an obvious set of comparisons between the persons and the stores of Snagsby and Krook that might be worth looking at. Snagsby deals with the orderly provision of paper and products to people who will do the writing and copying of documents. These days, we photocopy or computerize documents of value. In the 19C, the reproduction of legal documents was much more laborious. Krook collects the detritus of paper that has been produced and is deemed to be of little or no value.

Mr Snagsby is portrayed as a quiet, competent, meek, clean, and good business person, and is married to a rather fiery individual. She is called a Gusher. That name perfectly complements her “story character.” She is the business manager for Snagsby. In contrast, Krook is portrayed as a dirty, rather slovenly person in both habit and living conditions. His business is primarily in rags and bones. Unmarried, he has a rather ferocious cat called Lady Jane. I find these people and their establishments a very interesting comparison.

Dickens reintroduces Mr Tulkinghorn in this chapter. We learn that his house is “rusty and out of date.” It has heavy furniture, “obsolete tables,” and is lit by “old-fashioned silver candlesticks.” Very noticeable in Tulkinghorn’s home is that “everything that can have a lock has got one.” The most prominent feature is a ceiling painting of Allegory who presides over the home. Did you enjoy Dickens’s description of lawyers such as Tulkinghorn as “maggots in nuts.” This home and its owner certainly reflect each other. Locked tight like a nut, we find a maggot.

Tulkinghorn goes to Snagsby’s and inquires into the law-writer who copied some affidavits for Lady Dedlock. Snagsby, who keeps excellent records, is able to identify who the writer was. It was a man named Nemo. Now, in Latin, Nemo, means “no one.” That’s a mystery. Perhaps not, as Snagsby knows where Nemo lives and takes Tulkinghorn to ... where else? Yes. Nemo is a boarder with Mr Krook, and so off go Snagsby and Tulkinghorn to Krook’s rag and bone shop.

Oh my! There are so many coincidences here. In this one rather small area of London we learn that the offices of Snagsby, Krook, and Coavinses all are found. Is it me or is there a wonderful irony in the fact that an owner of a stationary store who employs people to write is taking a lawyer to a Rag and Bottle shop that is owned by a man who is illiterate to find a man who has a very distinctive writing style. Krook tells his visitors that there is a rumour that his boarder “has sold himself to the Enemy.”

Tulkinghorn ascends the stairs to Nemo’s room. I found Dickens’s description of what Tulkinghorn saw to be a masterful piece of writing. Tulkinghorn does find Nemo, the man he sought, but it is too late. Nemo is dead. And so ends the chapter.

Thoughts

This chapter has it all. Grand character development, suspense, incredible and suggestive descriptions of physical place and, of course, a good dose of coincidence. What part of the chapter did you enjoy most?

Why do you think Dickens has created such contrasting people and places so early in the novel?

In what ways did you find Dickens was continuing to blend and join seemingly unconnected parts of the plot together?

The Law-Writer

In this chapter we continue to slide deeper into the mystery of who was the writer of the document that so interested Lady Dedlock. That means we will spend some more time with Mr Tulkinghorn as well. Fist, however, we meet a couple of new characters and spend some time in a new location.

As a contrast to Krook and his rag shop of disused paper, we begin the chapter by meeting Mr Snagsby. He operates a stationary store that deals with all sorts of clean paper and forms concerning the legal process. I imagine a 19C equivalent of a Staples outlet. There is an obvious set of comparisons between the persons and the stores of Snagsby and Krook that might be worth looking at. Snagsby deals with the orderly provision of paper and products to people who will do the writing and copying of documents. These days, we photocopy or computerize documents of value. In the 19C, the reproduction of legal documents was much more laborious. Krook collects the detritus of paper that has been produced and is deemed to be of little or no value.

Mr Snagsby is portrayed as a quiet, competent, meek, clean, and good business person, and is married to a rather fiery individual. She is called a Gusher. That name perfectly complements her “story character.” She is the business manager for Snagsby. In contrast, Krook is portrayed as a dirty, rather slovenly person in both habit and living conditions. His business is primarily in rags and bones. Unmarried, he has a rather ferocious cat called Lady Jane. I find these people and their establishments a very interesting comparison.

Dickens reintroduces Mr Tulkinghorn in this chapter. We learn that his house is “rusty and out of date.” It has heavy furniture, “obsolete tables,” and is lit by “old-fashioned silver candlesticks.” Very noticeable in Tulkinghorn’s home is that “everything that can have a lock has got one.” The most prominent feature is a ceiling painting of Allegory who presides over the home. Did you enjoy Dickens’s description of lawyers such as Tulkinghorn as “maggots in nuts.” This home and its owner certainly reflect each other. Locked tight like a nut, we find a maggot.

Tulkinghorn goes to Snagsby’s and inquires into the law-writer who copied some affidavits for Lady Dedlock. Snagsby, who keeps excellent records, is able to identify who the writer was. It was a man named Nemo. Now, in Latin, Nemo, means “no one.” That’s a mystery. Perhaps not, as Snagsby knows where Nemo lives and takes Tulkinghorn to ... where else? Yes. Nemo is a boarder with Mr Krook, and so off go Snagsby and Tulkinghorn to Krook’s rag and bone shop.

Oh my! There are so many coincidences here. In this one rather small area of London we learn that the offices of Snagsby, Krook, and Coavinses all are found. Is it me or is there a wonderful irony in the fact that an owner of a stationary store who employs people to write is taking a lawyer to a Rag and Bottle shop that is owned by a man who is illiterate to find a man who has a very distinctive writing style. Krook tells his visitors that there is a rumour that his boarder “has sold himself to the Enemy.”

Tulkinghorn ascends the stairs to Nemo’s room. I found Dickens’s description of what Tulkinghorn saw to be a masterful piece of writing. Tulkinghorn does find Nemo, the man he sought, but it is too late. Nemo is dead. And so ends the chapter.

Thoughts

This chapter has it all. Grand character development, suspense, incredible and suggestive descriptions of physical place and, of course, a good dose of coincidence. What part of the chapter did you enjoy most?

Why do you think Dickens has created such contrasting people and places so early in the novel?

In what ways did you find Dickens was continuing to blend and join seemingly unconnected parts of the plot together?

At first glance, Snagsby's store must have been a kind of heaven for Victorian law stationery lovers, if it weren't for his wife. On the other hand, as soon as the red tape was mentioned I wanted out. I love the way this corner of London is painted though. It's all dusty, dark and dull in a way, it clearly needs a good shaking up. I hope the death of Nemo gives a bit of that. It also shows that Chancery does not only suck all life out of the upper class they use, but also out of people dangling onto it to keep going. Not even someone who does relatively well gaining from Chancery, like Snagsby, seems to be able to b happy. Only bats like Tulkinhorn seem to thrive in it.

Those were three incredible chapters, again. At first glance I dislike Mrs. Pardiggle even more than Mrs. Jellyby or Skimpole. I think mostly because her cold-heartedness is showing way more clearly. Mrs. Jellyby is obsessed, and as with a drug addict's obsession with their drug, it felt more like a part of an illness. Something that's very bad, but the control has slipped out of her fingers. Skimpole is mean and as we say here 'behind the elbows', but at least he still tries to be friendly and amusing to those he uses to get money. Mrs. Pardiggle is just cold, not only neglecting but using her children (something Skimpole isn't shown doing (yet) I believe). Mrs. Jellyby seems to just forget Caddy also needs to do/learn other things than writing, while Mrs. Pardiggle knows better, but just doesn't care. And the scene with that poor baby 😭 How heartless can you be to not even care about such things?

And yes, the chapter with both Boythorn and Guppy was amazing too. Boythorn is so wholesome! I now would love to know what he would say to people like Mrs. Pardiggle. She would be very offended, I'm sure. And Guppy, oh Guppy, pine away my dear little fishy. Did others notice too, that he was so 'lovestruck' now after the chapter at Chesney Wold, but not in the chapters before? Would there be a connection there, if only that his head is opened to unlikely, weird fancies? I can almost see his sad droopy face when Esther makes him sit behind his food again, to gain a little distance and a table between them, and he thought she was making him eat again! And him making it all like some kind of Chancery business arangement, with talking about his monetary worth and how his mother 'had her bad habits, but she only did it when there was no company, at which times she was to be trusted with liquors'. My mother in law is an alcoholic, and I laughed just a little bit too hard imagining my husband mentioning that 'at least she doesn't get drunk in front of other people' as if it were a boon to have such a mother in law. (Don't worry, we keep our distance from mine, since unlike Guppy my husband does not think 'at least she doesn't do it in front of others' as that redeeming)

Those were three incredible chapters, again. At first glance I dislike Mrs. Pardiggle even more than Mrs. Jellyby or Skimpole. I think mostly because her cold-heartedness is showing way more clearly. Mrs. Jellyby is obsessed, and as with a drug addict's obsession with their drug, it felt more like a part of an illness. Something that's very bad, but the control has slipped out of her fingers. Skimpole is mean and as we say here 'behind the elbows', but at least he still tries to be friendly and amusing to those he uses to get money. Mrs. Pardiggle is just cold, not only neglecting but using her children (something Skimpole isn't shown doing (yet) I believe). Mrs. Jellyby seems to just forget Caddy also needs to do/learn other things than writing, while Mrs. Pardiggle knows better, but just doesn't care. And the scene with that poor baby 😭 How heartless can you be to not even care about such things?

And yes, the chapter with both Boythorn and Guppy was amazing too. Boythorn is so wholesome! I now would love to know what he would say to people like Mrs. Pardiggle. She would be very offended, I'm sure. And Guppy, oh Guppy, pine away my dear little fishy. Did others notice too, that he was so 'lovestruck' now after the chapter at Chesney Wold, but not in the chapters before? Would there be a connection there, if only that his head is opened to unlikely, weird fancies? I can almost see his sad droopy face when Esther makes him sit behind his food again, to gain a little distance and a table between them, and he thought she was making him eat again! And him making it all like some kind of Chancery business arangement, with talking about his monetary worth and how his mother 'had her bad habits, but she only did it when there was no company, at which times she was to be trusted with liquors'. My mother in law is an alcoholic, and I laughed just a little bit too hard imagining my husband mentioning that 'at least she doesn't get drunk in front of other people' as if it were a boon to have such a mother in law. (Don't worry, we keep our distance from mine, since unlike Guppy my husband does not think 'at least she doesn't do it in front of others' as that redeeming)

Jantine wrote: "At first glance, Snagsby's store must have been a kind of heaven for Victorian law stationery lovers, if it weren't for his wife. On the other hand, as soon as the red tape was mentioned I wanted o..."

Jantine

Yes. The Guppy-Esther proposal is funny. For me, it was the first truly humourous part of the novel. I don’t find Skimpole’s attitude funny. To me he is just selfish. Perhaps we should’t expect too much humour in a novel with the title Bleak House.

The links you make with Guppy, Chesney Wold, and Esther are interesting. Is there something fishy going on? ;-)

Jantine

Yes. The Guppy-Esther proposal is funny. For me, it was the first truly humourous part of the novel. I don’t find Skimpole’s attitude funny. To me he is just selfish. Perhaps we should’t expect too much humour in a novel with the title Bleak House.

The links you make with Guppy, Chesney Wold, and Esther are interesting. Is there something fishy going on? ;-)

I am going to confine my comments to the first chapter for now since I have not read farther as yet:

Esther's first person narration clearly belies her constant protestations of her own intellectual limitations, especially when it comes to the description of Mrs. Pardiggle, where, as Peter says it, Dickens definitely has his knife out. The sarcams is not as biting and scathing as in the chapters seen through the omniscient narrator's perspective, but still the tone is rather ironic, and I cannot imagine the homespun Esther capable of such irony.

Interestingly, Esther says that she never had difficulty in making friends with children, but in the case of the Pardiggle children she fails to make any connection. Those brats - poor mistreated children, to be sure - vent their spleen on Esther as on the next best person. How much pent-up frustration must be sweltering in those little souls, and one can be sure that once they are grown up they will give any charity business a wide berth.

Compared to Mrs. Pardiggle, who talks at people rather than with them, Mrs. Jellyby is more likeable, in my opinion, and I think it is better to be a Jellyby child than a Pardiggle child: The Jellyby children are utterly neglected and probably don't even get any education, but at least they are free to roam and are not constrained in mind and soul.

Esther's first person narration clearly belies her constant protestations of her own intellectual limitations, especially when it comes to the description of Mrs. Pardiggle, where, as Peter says it, Dickens definitely has his knife out. The sarcams is not as biting and scathing as in the chapters seen through the omniscient narrator's perspective, but still the tone is rather ironic, and I cannot imagine the homespun Esther capable of such irony.

Interestingly, Esther says that she never had difficulty in making friends with children, but in the case of the Pardiggle children she fails to make any connection. Those brats - poor mistreated children, to be sure - vent their spleen on Esther as on the next best person. How much pent-up frustration must be sweltering in those little souls, and one can be sure that once they are grown up they will give any charity business a wide berth.

Compared to Mrs. Pardiggle, who talks at people rather than with them, Mrs. Jellyby is more likeable, in my opinion, and I think it is better to be a Jellyby child than a Pardiggle child: The Jellyby children are utterly neglected and probably don't even get any education, but at least they are free to roam and are not constrained in mind and soul.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 8

Peter wrote: "Chapter 8Do you find her or Mrs Jellyby to be the more interesting character?..."

Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle are two sides of the same coin. Somehow, Mrs. Pardiggle comes off as less likeable -- I guess because we see her interact with her beneficiaries. She's obviously more worried about doing her "Christian duty" and her reputation than she is about the people she's meant to be helping.

Jenny's husband is an interesting character. He's not likeable, certainly, but he comes across as very authentic, and his response to Mrs. Pardiggle's brand of "help" is a good lesson for all philanthropists. First, he didn't ask for help, and it's not appreciated. Second, Mrs. Pardiggle has not taken the time to get to know these people, let alone ASK if they'd like help, or what it is they may need. She provides what she thinks they should have. Finally, her "help" comes with strings attached -- leaving religious tracts, expecting them to be read by illiterate people, etc.

Plus, there's just the sheer audacity of it. I enjoyed this passage:

"There an't," growled the man on the floor, whose head rested on his hand as he stared at us, "any more on you to come in, is there?"

"No, my friend," said Mrs. Pardiggle, seating herself on one stool and knocking down another. "We are all here."

"Because I thought there warn't enough of you, perhaps?" said the man, with his pipe between his lips as he looked round upon us.

Imagine how tiny that dwelling must have been, and yet here Mrs. Pardiggle comes barging in - not on her own, but with five children and two other adults! Such cheek!

Jenny's husband is no saint, of course. He beats his wife and spends his time and money at the local tavern. But I wonder if Mrs. Pardiggle's interference doesn't exacerbate things by shining a spotlight on his shortcomings.

Peter, you didn't mention the foreshadowing that took place at the end of this chapter. I hope I'm not interfering with your plans for future discussions by pointing it out here...

How little I thought, when I raised my handkerchief to look upon the tiny sleeper underneath... how little I thought in whose unquiet bosom that handkerchief would come to lie, after covering the motionless and peaceful breast!

Peter wrote: "Chapter 9..."

I thought I'd finished chapter 9 and when I picked the book back up, I resumed at chapter 10, completely missing Guppy's proposal. As Dickens' humor is my favorite thing about his books, I must go back and read what I missed.

As for Boythorn, I love the description "stentorian", but I really don't care to be around people who might be described that way. A little goes a long way for me. But I think Peter's correct -- blustery as he may be, anyone who has a canary perched on his head must be a character we're meant to find endearing. How will Boythorn and Skimpole get along?

Peter wrote: "Chapter 10..."

Quite a lot to digest in this chapter. As I read Peter's summary, it struck me that Krook's establishment is colloquially known as "the court of Chancery", he's called "the Lord Chancellor", and his cat is called "Lady Jane" -- why the pretense? I assumed at first that it was tongue-in-cheek, and that his shop was called the court of Chancery sarcastically, because of all the chaos and papers. We'll have to see if there's more to it than just a study in contrasts.

Nemo seems to be a key to some of our mysteries, and yet we first meet him at his death. Dickens created some wonderful imagery with the starvation/famine allusions, the candle going out, etc. It was quite easy to imagine, and I look forward to any illustrations there may be of Nemo's quarters.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 8

Do you find her or Mrs Jellyby to be the more interesting character?..."

Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle are two sides of the same coin. Somehow, Mrs. Pardiggle comes off a..."

Hi Mary Lou

I’m quite happy when you pick up on what I have missed, neglected, or glossed over. There is always so much going on in each chapter on so many levels. The passage you mention with the handkerchief is indeed both moving and somber in its place and may well be magnified in the future. Thanks for pointing it out.

I also never thought of it before as a statement but you are right. The first time we meet Nemo he is dead. Often the dead come back as ghosts.

I’m thinking that it might be a good idea to count the dead and those who die in this novel and see how many come back to us as ghosts in one form or another.

Do you find her or Mrs Jellyby to be the more interesting character?..."

Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle are two sides of the same coin. Somehow, Mrs. Pardiggle comes off a..."

Hi Mary Lou

I’m quite happy when you pick up on what I have missed, neglected, or glossed over. There is always so much going on in each chapter on so many levels. The passage you mention with the handkerchief is indeed both moving and somber in its place and may well be magnified in the future. Thanks for pointing it out.

I also never thought of it before as a statement but you are right. The first time we meet Nemo he is dead. Often the dead come back as ghosts.

I’m thinking that it might be a good idea to count the dead and those who die in this novel and see how many come back to us as ghosts in one form or another.

Tristram wrote: "Is it me, or are Esther's nicknames yuck-able?"

Yes, they are. I mean, I looked up the Mother Hubbard-thing, and it's not nice at all:

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the Cupboard,

To give the poor Dog a bone;

When she came there,

The Cupboard was bare,

And so the poor Dog had none.

She went to the Bakers

To buy him some Bread;

When she came back

The Dog was dead!

She went to the Undertakers

To buy him a coffin;

When she came back

The Dog was laughing.

Then there's Mrs. Shipton. While looking her up, I thought this nickname might be something to write down and look up again at the end of the novel.

Yes, they are. I mean, I looked up the Mother Hubbard-thing, and it's not nice at all:

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the Cupboard,

To give the poor Dog a bone;

When she came there,

The Cupboard was bare,

And so the poor Dog had none.

She went to the Bakers

To buy him some Bread;

When she came back

The Dog was dead!

She went to the Undertakers

To buy him a coffin;

When she came back

The Dog was laughing.

Then there's Mrs. Shipton. While looking her up, I thought this nickname might be something to write down and look up again at the end of the novel.

The Guppy proposal was funny and so was “don’t tell anyone about it.” There was not any foreshadowing that I recall, so it was strange. I kept thinking it was related to paperwork he saw, somehow, but that seems too pernicious for his character.

The Guppy proposal was funny and so was “don’t tell anyone about it.” There was not any foreshadowing that I recall, so it was strange. I kept thinking it was related to paperwork he saw, somehow, but that seems too pernicious for his character.

Peter wrote: "She sees herself as a 'tiresome little creature.'"

And she proves an uncommon amout of judgment in that, I'd say. Just look at the beginning of the chapter, where she makes a show of writing more about herself than she was allegedly inclined to! What the heck! if you think you are writing too much about yourself, start a new page and write less about yourself then. Whom does she want to impress that way? Are we supposed to think that she is oh so modest now?

Peter mentioned that in this chapter, Dickens makes it clear that the Dedlocks are remote relations to the Jarndyces. This happens at least twice within the same chapter, and then there is another reference via Boythorn, and so I think we ought to keep it in mind. At any rate, it is one more thread in the web that Dickens is going to create.

I wonder how Mr. Boythorn, whom I like a lot (although I would not care to have a room next to the one he is sleeping and snoring in), would react if he ever found himself in the same room and at the same dinner table with Skimpole. Would he bear the latter's prattle about the bees and the drones? Or would he throw him out of the window?

Ah, Mr. Guppy - what a noble and romantic swain he is! Just notice how he tries to rally his spirits by downing three glasses of preparatory wine, and how he even offers a glass to Esther. How thoughtful! And the way he introduces the legalistic lingo into his declaration, making sure that what he is going to say will not be used against him. I must say he is entitled to look higher than to Esther Summerson ;-)

In addition to Peter's reference to his constant scrutinizing of Esther, I'd also like to point out to you what he says,

"'[...]Though a young man, I have ferreted out evidence, got up cases, and seen lots of life. Blest with your hand, what means might I not find of advancing your interests and pushing your fortunes! What might I not get to know, nearly concerning you? I know nothing now, certainly; but what might I not if I had your confidence, and you set me on?'"

What does he know or think he does that we don't know as yet? The plot definitely begins to thicken here, all the more so as Mr Jarndyce asked Esther, earlier in the chapter, whether she has any questions to ask him, implying questions about herself, and her family, and Esther, of course, replied that unless Mr. Jarndyce thought fit to speak on his own account, she will not seek to know anything out of her own motivation. Is Mr. Guppy about to find out things that Mr. Jarndyce already knows but does not think necessary for Esther to be acquainted with? What kind of explosive knowledge is this going to be?

I'll keep my fingers crossed for Mr. Guppy and shout: Go, Guppy, go!

And she proves an uncommon amout of judgment in that, I'd say. Just look at the beginning of the chapter, where she makes a show of writing more about herself than she was allegedly inclined to! What the heck! if you think you are writing too much about yourself, start a new page and write less about yourself then. Whom does she want to impress that way? Are we supposed to think that she is oh so modest now?

Peter mentioned that in this chapter, Dickens makes it clear that the Dedlocks are remote relations to the Jarndyces. This happens at least twice within the same chapter, and then there is another reference via Boythorn, and so I think we ought to keep it in mind. At any rate, it is one more thread in the web that Dickens is going to create.

I wonder how Mr. Boythorn, whom I like a lot (although I would not care to have a room next to the one he is sleeping and snoring in), would react if he ever found himself in the same room and at the same dinner table with Skimpole. Would he bear the latter's prattle about the bees and the drones? Or would he throw him out of the window?

Ah, Mr. Guppy - what a noble and romantic swain he is! Just notice how he tries to rally his spirits by downing three glasses of preparatory wine, and how he even offers a glass to Esther. How thoughtful! And the way he introduces the legalistic lingo into his declaration, making sure that what he is going to say will not be used against him. I must say he is entitled to look higher than to Esther Summerson ;-)

In addition to Peter's reference to his constant scrutinizing of Esther, I'd also like to point out to you what he says,

"'[...]Though a young man, I have ferreted out evidence, got up cases, and seen lots of life. Blest with your hand, what means might I not find of advancing your interests and pushing your fortunes! What might I not get to know, nearly concerning you? I know nothing now, certainly; but what might I not if I had your confidence, and you set me on?'"

What does he know or think he does that we don't know as yet? The plot definitely begins to thicken here, all the more so as Mr Jarndyce asked Esther, earlier in the chapter, whether she has any questions to ask him, implying questions about herself, and her family, and Esther, of course, replied that unless Mr. Jarndyce thought fit to speak on his own account, she will not seek to know anything out of her own motivation. Is Mr. Guppy about to find out things that Mr. Jarndyce already knows but does not think necessary for Esther to be acquainted with? What kind of explosive knowledge is this going to be?

I'll keep my fingers crossed for Mr. Guppy and shout: Go, Guppy, go!

Jantine wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Is it me, or are Esther's nicknames yuck-able?"

Yes, they are. I mean, I looked up the Mother Hubbard-thing, and it's not nice at all:

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the Cupboard,

To..."

Why are nursery rhymes often so morbid? I mean they are nursery rhymes rather than morgue rhymes, aren't they?

Yes, they are. I mean, I looked up the Mother Hubbard-thing, and it's not nice at all:

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the Cupboard,

To..."

Why are nursery rhymes often so morbid? I mean they are nursery rhymes rather than morgue rhymes, aren't they?

Mary Lou wrote: "Jenny's husband is no saint, of course. He beats his wife and spends his time and money at the local tavern. But I wonder if Mrs. Pardiggle's interference doesn't exacerbate things by shining a spotlight on his shortcomings."

But he is a pipe smoker, and as such has some small amount of credit in my books.

I just noticed, Mary Lou, that you too were wondering how Boythorn and Skimpole might get along. An intriguing question, isn't it? And did you notice what different sets of people centre around Mr. Jarndyce: There are annoying busybodies like the Jellybys and the Pardiggles of this world, a scrounger like Skimpole, an honest man like Boythorn and our juvenile trio. Did I forget anyone? Why is Jarndyce not more careful in the choice of his acquaintances? Can't he say no?

But he is a pipe smoker, and as such has some small amount of credit in my books.

I just noticed, Mary Lou, that you too were wondering how Boythorn and Skimpole might get along. An intriguing question, isn't it? And did you notice what different sets of people centre around Mr. Jarndyce: There are annoying busybodies like the Jellybys and the Pardiggles of this world, a scrounger like Skimpole, an honest man like Boythorn and our juvenile trio. Did I forget anyone? Why is Jarndyce not more careful in the choice of his acquaintances? Can't he say no?

Tristram wrote: "Why are nursery rhymes often so morbid? I mean they are nursery rhymes rather than morgue rhymes, aren't they?"

They're strange, that's what they are. I can't imagine why you would want to teach your children these things. There is:

Ring-a-round the rosie,

A pocket full of posies,

Ashes! Ashes!

We all fall down.

The invariable sneezing and falling down in modern English versions have given would-be origin finders the opportunity to say that the rhyme dates back to the Great Plague. A rosy rash, they allege, was a symptom of the plague, and posies of herbs were carried as protection and to ward off the smell of the disease. Sneezing or coughing was a final fatal symptom, and "all fall down" was exactly what happened. The line Ashes, Ashes in colonial versions of the rhyme is claimed to refer variously to cremation of the bodies, the burning of victims' houses, or blackening of their skin, and the theory has been adapted to be applied to other versions of the rhyme.

Then there's:

All around the cobbler’s bench

The monkey chased the weasel;

The monkey thought 'twas all in good fun,

Pop! goes the weasel.

Up and down the King's Road,

In and out the Eagle,

That's the way the money goes—

Pop! goes the weasel.

A penny for a spool of thread,

A penny for a needle—

That's the way the money goes,

Pop! goes the weasel.

Jimmy’s got the whooping cough

And Timmy’s got the measles.

That’s the way the story goes,

Pop! goes the weasel.

Perhaps because of the obscure nature of the various lyrics there have been many suggestions for what they mean, particularly the phrase "Pop! goes the weasel", including: that it is a tailor's flat iron, a dead weasel, a hatter's tool, a spinner's weasel used for measuring in spinning, a piece of silver plate, or that weasel and stoat is Cockney rhyming slang for throat, as in "get that down yer weasel", meaning to eat or drink something.

An alternative meaning which fits better with the theme of "that's the way the money goes" involves pawning one's coat in desperation to buy food and drink, as "weasel (and stoat)" is more usually and traditionally Cockney rhyming slang for coat than throat and "pop" is a slang word for pawn. Therefore, "Pop goes the weasel" meant pawning a coat. Decent coats and other clothes were handmade, expensive and pawnable. A "monkey on the house" is slang for a mortgage or other secured loan. If knocked off the table or ignored it would go unpaid and accrue interest, requiring the coat to be pawned again.

Next we have:

Eena, meena, mina, mo,

Catch a nigger by his toe;

If he squeals let him go,

Eena, meena, mina, mo.

This version was similar to that reported by Henry Carrington Bolton as the most common version among American schoolchildren in 1888. It was used in the chorus of Bert Fitzgibbon's 1906 song "Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo":

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo,

Catch a nigger by the toe,

If he won't work then let him go;

Skidum, skidee, skidoo.

But when you get money, your little bride

Will surely find out where you hide,

So there's the door and when I count four,

Then out goes you.

It was also used by Rudyard Kipling in his "A Counting-Out Song", from Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides, published in 1935. This may have helped popularise this version in the United Kingdom where it seems to have replaced all earlier versions until the late twentieth century.

Iona and Peter Opie pointed out in The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (1951) that the word "nigger" was common in American folklore, but unknown in any English traditional rhyme or proverb. This, combined with evidence of various other versions of the rhyme in the British Isles pre-dating this post-slavery version, would seem to suggest that it originated in North America, although the apparently American word "holler" was first recorded in written form in England in the 14th century, whereas according to the Oxford English Dictionary the words "Niger" or "'nigger" were first recorded in England in the 16th century with their current disparaging meaning. The 'olla' and 'toe' are found as nonsense words in some 19th century versions of the rhyme.

And finally:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the King's horses

And all the King's men,

Couldn't put Humpty together again.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the 17th century the term "humpty dumpty" referred to a drink of brandy boiled with ale. The riddle probably exploited, for misdirection, the fact that "humpty dumpty" was also eighteenth-century reduplicative slang for a short and clumsy person. The riddle may depend upon the assumption that a clumsy person falling off a wall might not be irreparably damaged, whereas an egg would be. The rhyme is no longer posed as a riddle, since the answer is now so well known. Similar riddles have been recorded by folklorists in other languages, such as "Boule Boule" in French, "Lille Trille" in Swedish and Norwegian, and "Runtzelken-Puntzelken" or "Humpelken-Pumpelken" in different parts of Germany—although none is as widely known as Humpty Dumpty is in English.

The rhyme does not explicitly state that the subject is an egg, possibly because it may have been originally posed as a riddle. There are also various theories of an original "Humpty Dumpty". One, advanced by Katherine Elwes Thomas in 1930 and adopted by Robert Ripley, posits that Humpty Dumpty is King Richard III of England, depicted as humpbacked in Tudor histories and particularly in Shakespeare's play, and who was defeated, despite his armies, at Bosworth Field in 1485.

In 1785, Francis Grose's Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue noted that a "Humpty Dumpty" was "a short clumsey [sic] person of either sex, also ale boiled with brandy"; no mention was made of the rhyme.

Punch in 1842 suggested jocularly that the rhyme was a metaphor for the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey; just as Wolsey was not buried in his intended tomb, so Humpty Dumpty was not buried in his shell.

Professor David Daube suggested in The Oxford Magazine of 16 February 1956 that Humpty Dumpty was a "tortoise" siege engine, an armoured frame, used unsuccessfully to approach the walls of the Parliamentary-held city of Gloucester in 1643 during the Siege of Gloucester in the English Civil War. This was on the basis of a contemporary account of the attack, but without evidence that the rhyme was connected. The theory was part of an anonymous series of articles on the origin of nursery rhymes and was widely acclaimed in academia, but it was derided by others as "ingenuity for ingenuity's sake" and declared to be a spoof. The link was nevertheless popularised by a children's opera All the King's Men by Richard Rodney Bennett, first performed in 1969.

From 1996, the website of the Colchester tourist board attributed the origin of the rhyme to a cannon recorded as used from the church of St Mary-at-the-Wall by the Royalist defenders in the siege of 1648. In 1648, Colchester was a walled town with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. The story given was that a large cannon, which the website claimed was colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty, which caused the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists (or Cavaliers, "all the King's men") attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty on to another part of the wall, but the cannon was so heavy that "All the King's horses and all the King's men couldn't put Humpty together again". Author Albert Jack claimed in his 2008 book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes that there were two other verses supporting this claim. Elsewhere, he claimed to have found them in an "old dusty library, [in] an even older book", but did not state what the book was or where it was found. It has been pointed out that the two additional verses are not in the style of the seventeenth century or of the existing rhyme, and that they do not fit with the earliest printed versions of the rhyme, which do not mention horses and men.

They're strange, that's what they are. I can't imagine why you would want to teach your children these things. There is:

Ring-a-round the rosie,

A pocket full of posies,

Ashes! Ashes!

We all fall down.

The invariable sneezing and falling down in modern English versions have given would-be origin finders the opportunity to say that the rhyme dates back to the Great Plague. A rosy rash, they allege, was a symptom of the plague, and posies of herbs were carried as protection and to ward off the smell of the disease. Sneezing or coughing was a final fatal symptom, and "all fall down" was exactly what happened. The line Ashes, Ashes in colonial versions of the rhyme is claimed to refer variously to cremation of the bodies, the burning of victims' houses, or blackening of their skin, and the theory has been adapted to be applied to other versions of the rhyme.

Then there's:

All around the cobbler’s bench

The monkey chased the weasel;

The monkey thought 'twas all in good fun,

Pop! goes the weasel.

Up and down the King's Road,

In and out the Eagle,

That's the way the money goes—

Pop! goes the weasel.

A penny for a spool of thread,

A penny for a needle—

That's the way the money goes,

Pop! goes the weasel.

Jimmy’s got the whooping cough

And Timmy’s got the measles.

That’s the way the story goes,

Pop! goes the weasel.

Perhaps because of the obscure nature of the various lyrics there have been many suggestions for what they mean, particularly the phrase "Pop! goes the weasel", including: that it is a tailor's flat iron, a dead weasel, a hatter's tool, a spinner's weasel used for measuring in spinning, a piece of silver plate, or that weasel and stoat is Cockney rhyming slang for throat, as in "get that down yer weasel", meaning to eat or drink something.

An alternative meaning which fits better with the theme of "that's the way the money goes" involves pawning one's coat in desperation to buy food and drink, as "weasel (and stoat)" is more usually and traditionally Cockney rhyming slang for coat than throat and "pop" is a slang word for pawn. Therefore, "Pop goes the weasel" meant pawning a coat. Decent coats and other clothes were handmade, expensive and pawnable. A "monkey on the house" is slang for a mortgage or other secured loan. If knocked off the table or ignored it would go unpaid and accrue interest, requiring the coat to be pawned again.

Next we have:

Eena, meena, mina, mo,

Catch a nigger by his toe;

If he squeals let him go,

Eena, meena, mina, mo.

This version was similar to that reported by Henry Carrington Bolton as the most common version among American schoolchildren in 1888. It was used in the chorus of Bert Fitzgibbon's 1906 song "Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo":

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo,

Catch a nigger by the toe,

If he won't work then let him go;

Skidum, skidee, skidoo.

But when you get money, your little bride

Will surely find out where you hide,

So there's the door and when I count four,

Then out goes you.

It was also used by Rudyard Kipling in his "A Counting-Out Song", from Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides, published in 1935. This may have helped popularise this version in the United Kingdom where it seems to have replaced all earlier versions until the late twentieth century.

Iona and Peter Opie pointed out in The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (1951) that the word "nigger" was common in American folklore, but unknown in any English traditional rhyme or proverb. This, combined with evidence of various other versions of the rhyme in the British Isles pre-dating this post-slavery version, would seem to suggest that it originated in North America, although the apparently American word "holler" was first recorded in written form in England in the 14th century, whereas according to the Oxford English Dictionary the words "Niger" or "'nigger" were first recorded in England in the 16th century with their current disparaging meaning. The 'olla' and 'toe' are found as nonsense words in some 19th century versions of the rhyme.

And finally:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the King's horses

And all the King's men,

Couldn't put Humpty together again.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the 17th century the term "humpty dumpty" referred to a drink of brandy boiled with ale. The riddle probably exploited, for misdirection, the fact that "humpty dumpty" was also eighteenth-century reduplicative slang for a short and clumsy person. The riddle may depend upon the assumption that a clumsy person falling off a wall might not be irreparably damaged, whereas an egg would be. The rhyme is no longer posed as a riddle, since the answer is now so well known. Similar riddles have been recorded by folklorists in other languages, such as "Boule Boule" in French, "Lille Trille" in Swedish and Norwegian, and "Runtzelken-Puntzelken" or "Humpelken-Pumpelken" in different parts of Germany—although none is as widely known as Humpty Dumpty is in English.

The rhyme does not explicitly state that the subject is an egg, possibly because it may have been originally posed as a riddle. There are also various theories of an original "Humpty Dumpty". One, advanced by Katherine Elwes Thomas in 1930 and adopted by Robert Ripley, posits that Humpty Dumpty is King Richard III of England, depicted as humpbacked in Tudor histories and particularly in Shakespeare's play, and who was defeated, despite his armies, at Bosworth Field in 1485.

In 1785, Francis Grose's Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue noted that a "Humpty Dumpty" was "a short clumsey [sic] person of either sex, also ale boiled with brandy"; no mention was made of the rhyme.

Punch in 1842 suggested jocularly that the rhyme was a metaphor for the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey; just as Wolsey was not buried in his intended tomb, so Humpty Dumpty was not buried in his shell.

Professor David Daube suggested in The Oxford Magazine of 16 February 1956 that Humpty Dumpty was a "tortoise" siege engine, an armoured frame, used unsuccessfully to approach the walls of the Parliamentary-held city of Gloucester in 1643 during the Siege of Gloucester in the English Civil War. This was on the basis of a contemporary account of the attack, but without evidence that the rhyme was connected. The theory was part of an anonymous series of articles on the origin of nursery rhymes and was widely acclaimed in academia, but it was derided by others as "ingenuity for ingenuity's sake" and declared to be a spoof. The link was nevertheless popularised by a children's opera All the King's Men by Richard Rodney Bennett, first performed in 1969.

From 1996, the website of the Colchester tourist board attributed the origin of the rhyme to a cannon recorded as used from the church of St Mary-at-the-Wall by the Royalist defenders in the siege of 1648. In 1648, Colchester was a walled town with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. The story given was that a large cannon, which the website claimed was colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty, which caused the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists (or Cavaliers, "all the King's men") attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty on to another part of the wall, but the cannon was so heavy that "All the King's horses and all the King's men couldn't put Humpty together again". Author Albert Jack claimed in his 2008 book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes that there were two other verses supporting this claim. Elsewhere, he claimed to have found them in an "old dusty library, [in] an even older book", but did not state what the book was or where it was found. It has been pointed out that the two additional verses are not in the style of the seventeenth century or of the existing rhyme, and that they do not fit with the earliest printed versions of the rhyme, which do not mention horses and men.

Peter wrote: "Yes. The Guppy-Esther proposal is funny. For me, it was the first truly humourous part of the novel."

Peter wrote: "Yes. The Guppy-Esther proposal is funny. For me, it was the first truly humourous part of the novel."Guppy reminds me of Mr. Collins from Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Except broke. :)

Peter wrote: "We learn that Esther and Ada spend much time together at Bleak House and that Richard is a rather restless character who, while not exactly like Mr Micawber, is a person who needs to have more control over his finances."

Peter wrote: "We learn that Esther and Ada spend much time together at Bleak House and that Richard is a rather restless character who, while not exactly like Mr Micawber, is a person who needs to have more control over his finances."Richard's attitude toward his finances is one of the few parts of this book I have remembered very well because as difficult as it would be to live with, I find his accounting comical and all too easy to identify with.

"I made ten pounds, clear, out of Coavinses' business."

"How was that?" said I.

"Why, I got rid of ten pounds which I was quite content to get rid of and never expected to see any more. You don't deny that?"

"No," said I.

"Very well! Then I came into possession of ten pounds—"

"The same ten pounds," I hinted.

"That has nothing to do with it!" returned Richard. "I have got ten pounds more than I expected to have, and consequently I can afford to spend it without being particular."

I absolutely tell myself some days, 'well, I didn't pick up a scone at the coffee shop, so that's four extra dollars I have now!" $4 is not so bad but it would be easy for that kind of thinking to get out of hand if it involved larger sums. There's a kind of pseudo-logic to it.

Julie wrote: "I find his accounting comical and all too easy to identify with. ..."

Julie wrote: "I find his accounting comical and all too easy to identify with. ..."Re: Richard's accounting, there's a wonderful old movie called "Life With Father" that has a great scene with Irene Dunne employing a similar budgeting strategy. Enjoy...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ig8y7...

Kim wrote: "Ring-a-round the rosie,

Kim wrote: "Ring-a-round the rosie,A pocket full of posies,

Ashes! Ashes!

We all fall down..."

I was visiting my granddaughters the other day, and the 3-year-old was playing nicely by herself, and making up a song on the spot about her little toy people going to the hospital because they had COVID. My daughter and I were stunned. I remarked at the time that now the whole Ring Around the Rosie thing made sense.

Pestilence was much less removed from people in the past. No hospitals, nursing homes, morgues, etc. Children were exposed to it. Of course they'd make up songs and games about it. I have to say, though, it was a startling moment to hear my innocent little girl singing about COVID.

(FYI - she's fairly sheltered. They don't watch TV, and she has no older siblings. They've had to explain it a bit - why she has to wear a mask sometimes, and why she can't see friends and some other relatives. But, my God, kids soak up everything they hear!)

As far as first person narrators go it's almost as if in Bleak House Dickens wanted to do the exact opposite of what he did in David Copperfield. We go from a male hero who turns out not to be such a hero after all to a female non-entity who turns out to be a heroine. Perhaps in Great Expectations we'll get a hero who's a hero all the way through.

As far as first person narrators go it's almost as if in Bleak House Dickens wanted to do the exact opposite of what he did in David Copperfield. We go from a male hero who turns out not to be such a hero after all to a female non-entity who turns out to be a heroine. Perhaps in Great Expectations we'll get a hero who's a hero all the way through. Guppy reminds me of Traddles. Ridiculous and endearing a the same time. The wooing scene was just perfect.

I hope we get to see more of the truculent Boythorn. I can't help but picture him as looking like le Capitaine Haddock from Tintin (must be my Belgian side).

There are so many great Dickensian details in these chapters, like Mrs. Pardiggle's dress knocking down small articles of furniture every time she moves about a room. Such great writing.

Ulysse wrote: "As far as first person narrators go it's almost as if in Bleak House Dickens wanted to do the exact opposite of what he did in David Copperfield. We go from a male hero who turns out not to be such..."

Hi Ulysse

Yes. Dickens’s use of the first person narrator is very interesting to track and consider. We are still reasonably early in BH but, like you, I suspect Esther will give us a few surprises along the way. At the end of BH I hope we can all have an interesting discussion about Esther and David.

Pardiggle is a great character. And Boythorn with the bird on his head! And then there is Mr Guppy. I don’t think any novelist has such a broad brush and creative mind as Dickens.

Hi Ulysse

Yes. Dickens’s use of the first person narrator is very interesting to track and consider. We are still reasonably early in BH but, like you, I suspect Esther will give us a few surprises along the way. At the end of BH I hope we can all have an interesting discussion about Esther and David.

Pardiggle is a great character. And Boythorn with the bird on his head! And then there is Mr Guppy. I don’t think any novelist has such a broad brush and creative mind as Dickens.

My sense is, Dickens needed to have Esther speak in the first person because there was no other way to get to know her. And she is an open book, which I find stands in marked contrast to almost all of the other characters introduced so far.

My sense is, Dickens needed to have Esther speak in the first person because there was no other way to get to know her. And she is an open book, which I find stands in marked contrast to almost all of the other characters introduced so far.

Mary Lou wrote: "Julie wrote: "I find his accounting comical and all too easy to identify with. ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Julie wrote: "I find his accounting comical and all too easy to identify with. ..."Re: Richard's accounting, there's a wonderful old movie called "Life With Father" that has a great scene with Ir..."

ha--maybe if Richard took up sobbing on a sofa his bookkeeping would be more persuasive!

Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had time to read through all the comments yet). Esther's narrative is in the past tense, whereas the omniscient narrator's is in the present. Had Dickens used the present tense to this extent in his novels before Bleak House? Why do you think he chose to use it here?

Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had time to read through all the comments yet). Esther's narrative is in the past tense, whereas the omniscient narrator's is in the present. Had Dickens used the present tense to this extent in his novels before Bleak House? Why do you think he chose to use it here?

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Why are nursery rhymes often so morbid? I mean they are nursery rhymes rather than morgue rhymes, aren't they?"

They're strange, that's what they are. I can't imagine why you wou..."

Here we go: They are all gruesome, aren't they?

They're strange, that's what they are. I can't imagine why you wou..."

Here we go: They are all gruesome, aren't they?

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "We learn that Esther and Ada spend much time together at Bleak House and that Richard is a rather restless character who, while not exactly like Mr Micawber, is a person who needs to ..."

I must say that I am also quite inclined to think in Richard's terms of saving money :-)

I must say that I am also quite inclined to think in Richard's terms of saving money :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "Ring-a-round the rosie,

A pocket full of posies,

Ashes! Ashes!

We all fall down..."

I was visiting my granddaughters the other day, and the 3-year-old was playing nicely by herself, an..."

You are right, Mary Lou. Those nursery rhymes were probably a way of making children come to terms with the threats of everday life. Children have a strange way of bringing these things up: My daughter loved to play Father, Mother, Children - and often, appallingly, she would play that the Mother had died and the family had to get by without a mother. I wonder where she got that idea, because we know no family where this has actually happened.

A pocket full of posies,

Ashes! Ashes!

We all fall down..."

I was visiting my granddaughters the other day, and the 3-year-old was playing nicely by herself, an..."

You are right, Mary Lou. Those nursery rhymes were probably a way of making children come to terms with the threats of everday life. Children have a strange way of bringing these things up: My daughter loved to play Father, Mother, Children - and often, appallingly, she would play that the Mother had died and the family had to get by without a mother. I wonder where she got that idea, because we know no family where this has actually happened.

Ulysse wrote: "Guppy reminds me of Traddles. Ridiculous and endearing a the same time. The wooing scene was just perfect.

I hope we get to see more of the truculent Boythorn. I can't help but picture him as looking like le Capitaine Haddock from Tintin (must be my Belgian side)."

It's nice to see I am not the only one here who has taken an instant liking to Mr. Guppy - for all his weaknesses.

I happen to think of Mr. Boythorn as some kind of personified blunderbuss :-)

I hope we get to see more of the truculent Boythorn. I can't help but picture him as looking like le Capitaine Haddock from Tintin (must be my Belgian side)."

It's nice to see I am not the only one here who has taken an instant liking to Mr. Guppy - for all his weaknesses.

I happen to think of Mr. Boythorn as some kind of personified blunderbuss :-)

Ulysse wrote: "Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had time to read throu..."

At my first reading, I was quite stunned by the use of the present tense in those chapters. I think it is a good way of telling the reader via the tense used what narrator they are going to meet in the chapter. I also find the present tense narrator very, very scathing and sometimes even sarcastic. Needless to say, I am enjoying him a lot more than Esther.

At my first reading, I was quite stunned by the use of the present tense in those chapters. I think it is a good way of telling the reader via the tense used what narrator they are going to meet in the chapter. I also find the present tense narrator very, very scathing and sometimes even sarcastic. Needless to say, I am enjoying him a lot more than Esther.

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Guppy reminds me of Traddles. Ridiculous and endearing a the same time. The wooing scene was just perfect.

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Guppy reminds me of Traddles. Ridiculous and endearing a the same time. The wooing scene was just perfect.I hope we get to see more of the truculent Boythorn. I can't help but pict..."

Blunderbuss, now there's a wonderful word and a perfect way to describe Boythorn. A blunderbuss firing blanks, that is.

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had tim..."

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had tim..."You really don't like Esther, do you Tristram :-)

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had tim..."

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Has anyone noticed the different tenses used by the two narrators of the novel? (sorry if I'm repeating anyone else's question; I fell behind the reading schedule and haven't had tim..."The present tense certainly feels urgent and somewhat journalistic. Maybe that note of sarcasm we hear is the voice of Boz resurfacing after all these years.

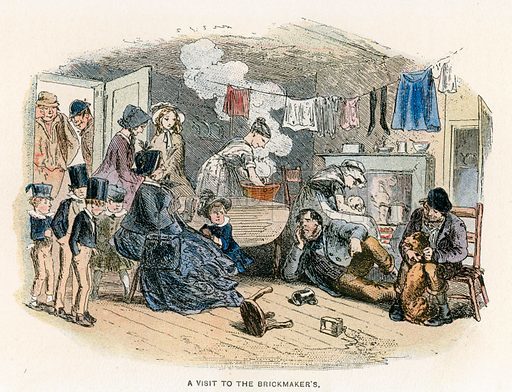

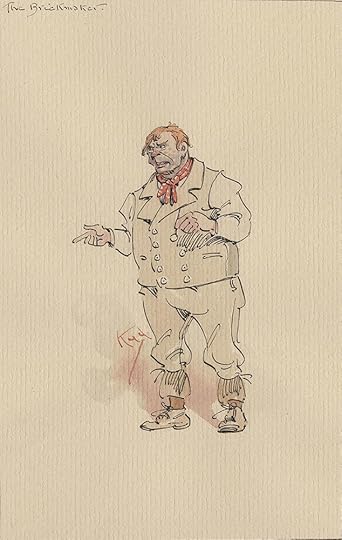

The Visit to the Brickmaker's

Chapter 8

Phiz

"Mrs. Pardiggle, leading the way with a great show of moral determination and talking with much volubility about the untidy habits of the people (though I doubted if the best of us could have been tidy in such a place), conducted us into a cottage at the farthest corner, the ground-floor room of which we nearly filled. Besides ourselves, there were in this damp, offensive room a woman with a black eye, nursing a poor little gasping baby by the fire; a man, all stained with clay and mud and looking very dissipated, lying at full length on the ground, smoking a pipe; a powerful young man fastening a collar on a dog; and a bold girl doing some kind of washing in very dirty water. They all looked up at us as we came in, and the woman seemed to turn her face towards the fire as if to hide her bruised eye; nobody gave us any welcome."

Commentary:

"Dickens, here very much a disciple of Carlyle, particularly the Carlyle of "Signs of the Times", draws a fierce satiric portrait of Mrs. Pardiggle's mechanical charity, which he opposes both to Mrs. Jellby's approach that involves abandoning her family and to the personal, individual charitable actions of both Esther and Mr. Jarndyce. The death of the baby and the reactions of the brickmaker's family, Esther, and Ada, which modern readers might take as excessively sentimental, had a definite political purpose that would have produced different results upon Victorian readers. In essence, Dickens here counters the belief frequently voiced by contemporary middle- and upper-class commentators that the poor "are different from us," they do not find the death of children all that upsetting, and they therefore must be almost a separate species. As Engles pointed out in his Condition of the Working Classes, the prosperous classes lived segregated from the poor, which prevented them from encountering their sufferings. Dickens here forces his reader to see these sufferings — an approach Mrs. Gaskell used two years later in North and South when her protagonist several times visits the poor in the manner of Esther and not Mrs. Pardiggle."

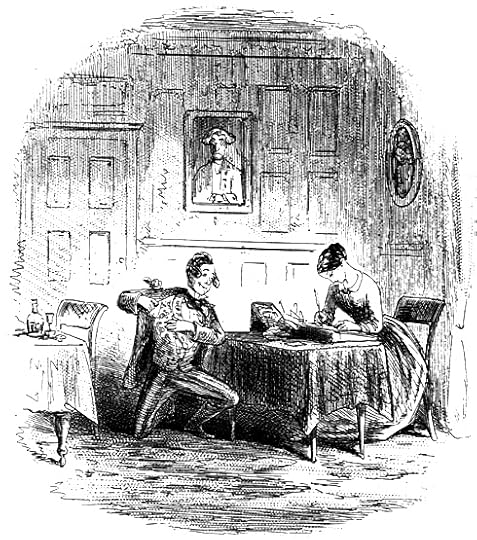

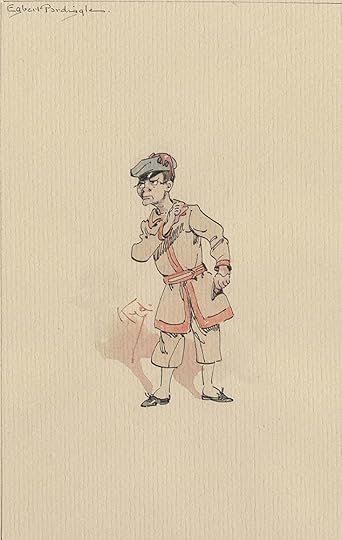

In Re Guppy. Extraordinary Proceedings

Chapter 9

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Guppy went down on his knees. I was well behind my table and not much frightened. I said, "Get up from that ridiculous position immediately, sir, or you will oblige me to break my implied promise and ring the bell!"

"Hear me out, miss!" said Mr. Guppy, folding his hands.

"I cannot consent to hear another word, sir," I returned, "Unless you get up from the carpet directly and go and sit down at the table as you ought to do if you have any sense at all."

The Growley

Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Sit down, my dear," said Mr. Jarndyce. "This, you must know, is the growlery. When I am out of humour, I come and growl here."

"You must be here very seldom, sir," said I.

"Oh, you don't know me!" he returned. "When I am deceived or disappointed in—the wind, and it's easterly, I take refuge here. The growlery is the best-used room in the house. You are not aware of half my humours yet. My dear, how you are trembling!"

I could not help it; I tried very hard, but being alone with that benevolent presence, and meeting his kind eyes, and feeling so happy and so honoured there, and my heart so full—I kissed his hand. I don't know what I said, or even that I spoke. He was disconcerted and walked to the window; I almost believed with an intention of jumping out, until he turned and I was reassured by seeing in his eyes what he had gone there to hide. He gently patted me on the head, and I sat down.

"There! There!" he said. "That's over. Pooh! Don't be foolish."

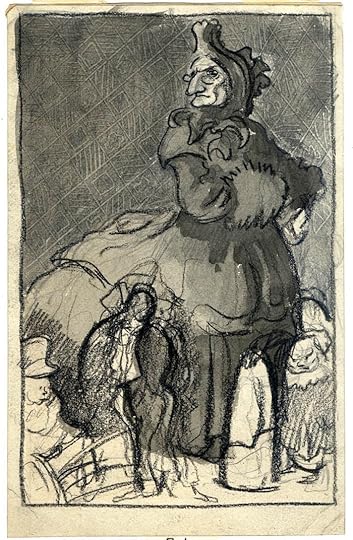

"Alfred, my youngest (five), has voluntarily enrolled himself in the infant bonds of joy, and is pledged never, through life, to use tobacco in any form"

Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"They attend matins with me (very prettily done) at half-past six o'clock in the morning all the year round, including of course the depth of winter," said Mrs. Pardiggle rapidly, "and they are with me during the revolving duties of the day. I am a School lady, I am a Visiting lady, I am a Reading lady, I am a Distributing lady; I am on the local Linen Box Committee and many general committees; and my canvassing alone is very extensive—perhaps no one's more so. But they are my companions everywhere; and by these means they acquire that knowledge of the poor, and that capacity of doing charitable business in general—in short, that taste for the sort of thing—which will render them in after life a service to their neighbours and a satisfaction to themselves. My young family are not frivolous; they expend the entire amount of their allowance in subscriptions, under my direction; and they have attended as many public meetings and listened to as many lectures, orations, and discussions as generally fall to the lot of few grown people. Alfred (five), who, as I mentioned, has of his own election joined the Infant Bonds of Joy, was one of the very few children who manifested consciousness on that occasion after a fervid address of two hours from the chairman of the evening."

Alfred glowered at us as if he never could, or would, forgive the injury of that night.

"If I were in your place I would seize every Master in Chancery by the throat to-morrow morning, and shake him until his money rolled out of his pockets, and his bones rattled in his skin"

Chapter 9

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"By my soul, Jarndyce," he said, very gently holding up a bit of bread to the canary to peck at, "if I were in your place I would seize every master in Chancery by the throat to-morrow morning and shake him until his money rolled out of his pockets and his bones rattled in his skin. I would have a settlement out of somebody, by fair means or by foul. If you would empower me to do it, I would do it for you with the greatest satisfaction!" (All this time the very small canary was eating out of his hand.)

"I thank you, Lawrence, but the suit is hardly at such a point at present," returned Mr. Jarndyce, laughing, "that it would be greatly advanced even by the legal process of shaking the bench and the whole bar."

"There never was such an infernal cauldron as that Chancery on the face of the earth!" said Mr. Boythorn. "Nothing but a mine below it on a busy day in term time, with all its records, rules, and precedents collected in it and every functionary belonging to it also, high and low, upward and downward, from its son the Accountant-General to its father the Devil, and the whole blown to atoms with ten thousand hundredweight of gunpowder, would reform it in the least!"

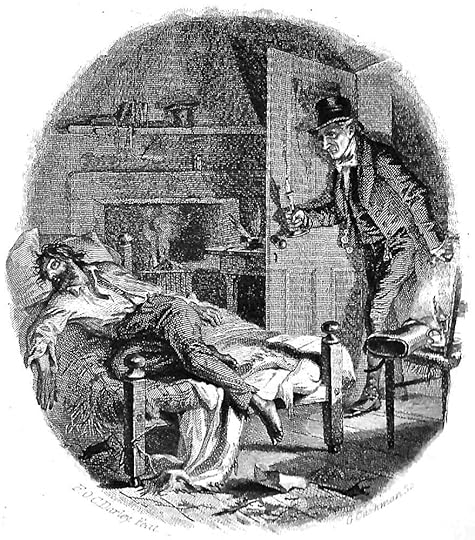

For on a low bed opposite the fire, a confusion of dirty patchwork, lean-ribbed ticking . . .

Chapter 10

Felix O. C. Darley

1863

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Tulkinghorn . . . comes to the dark door on the second floor. He knocks, receives no answer, opens it, and accidentally extinguishes his candle in doing so.

The air of the room is almost bad enough to have extinguished it if he had not. It is a small room, nearly black with soot, and grease, and dirt. In the rusty skeleton of a grate, pinched at the middle as if Poverty had gripped it, a red coke fire burns low. In the corner by the chimney, stand a deal table and a broken desk: a wilderness marked with a rain of ink. In another corner, a ragged old portmanteau on one of the two chairs, serves for cabinet or wardrobe; no larger one is needed, for it collapses like the cheeks of a starved man. The floor is bare; except that one old mat, trodden to shreds of rope-yarn, lies perishing upon the hearth. No curtain veils the darkness of the night, but the discolored shutters are drawn together; and through the two gaunt holes pierced in them, famine might be staring in — the Banshee of the man upon the bed.

For, on a low bed opposite the fire, a confusion of dirty patchwork, lean-ribbed ticking, and coarse sacking, the lawyer, hesitating just within the doorway, sees a man. He lies there, dressed in shirt and trousers, with bare feet. He has a yellow look in the spectral darkness of a candle that has guttered down, until the whole length of its wick (still burning) has doubled over, and left a tower of winding-sheet above it. His hair is ragged, mingling with his whiskers and his beard — the latter, ragged too, and grown, like the scum and mist around him, in neglect. Foul and filthy as the room is, foul and filthy as the air, it is not easy to perceive what fumes those are which most oppress the senses in it; but through the general sickliness and faintness, and the odor of stale tobacco, there comes into the lawyer's mouth the bitter, vapid taste of opium.

"Hallo, my friend!" he cries, and strikes his iron candlestick against the door.

Commentary:

Darley has chosen a lengthy quotation for his caption so that the reader can easily locate the passage and reflect upon the situation realised: “On a low bed opposite the fire, a confusion of dirty patchwork, lean-ribbed ticking, and coarse sacking, the lawyer, hesitating just within the doorway, sees a man.”

Darley has chosen a suspenseful moment at the close of a chapter as an investigator enters a room and encounters a mystery. Here the investigator is the lawyer, Tulkinghorn, and the mystery is whether the legal copyist or law-writer "Nemo" is alive or dead. The reader, having already encountered this part of the plot in the text, now reviews it in the illustration, which in its depiction of the investigative attorney follows the description of Tulkinghorn in Chapter 2: