The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Bleak House

>

Bleak House Chapters 11-13

Chapter 12

On the Watch

The epigraph for this chapter in “On the Watch.” I wonder if that means we as readers should be on the watch for something or someone, or if a character in the chapter is on the watch for something or someone? Perhaps it is both those possibilities. Let’s take a look.

The chapter begins with Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock leaving France and returning to England. Apparently, Lady Dedlock is totally bored with Paris and will be less bored at home. For his part, when Sir Leicester is bored, we are told that “when he has nothing else to do, he can always contemplate his own greatness.” A party is planned and so we find Chesney Wold in preparation as some rather important English friends including Tulkinghorn are expected. We also learn that Tulkinghorn has something to tell Lady Dedlock.

Mrs Rouncewell welcomes the Dedlock’s home. Lady Dedlock spots a servant named Rosa, and bids Mrs Rouncewell and her new associate to approach. Lady Dedlock compliments Rosa on her beauty and learns that Rosa is 19 years old. In a curious turn of phrase Lady Dedlock tells Rosa to “take care they don’t spoil you by flattery.” That night Mrs Rouncewell muses that it is “almost a pity” that Lady Dedlock does not have a daughter.

We learn that Lady Dedlock has a French maid who is 32 years old. Her name is Hortense and her description is a bit unsettling. Words such as “feline mouth,” and “jaws too eager,” as well as the fact that when she is in an “ill humour and near knives” Hortense is something “like a very neat She-Wolf imperfectly tamed.” Now, that’s not a person most of us would feel comfortable around. Why would Lady Dedlock hire someone like Hortense attend her? That is something to be on the watch for in the future. Next, Dickens goes into a long list of ridiculous names of men who are connected to Parliament and are attending the party. I think it fair to say that Dickens’s opinion of Parliamentarians is rather low.

To me, the key part of this chapter is the extremely interesting interplay between Lady Dedlock and Tulkinghorn. First, we learn that Tulkinghorn has his own exclusive room in Chesney Wold. Lady Dedlock waits, and waits, for him to arrive. Finally, he “appears.” Interesting word “appears.” What does that word suggest to you? Tulkinghorn explains the reason for his late arrival is because he was engaged with “several suits between yourself and Boythorn.” Sir Leicester refuses to budge from his position. Having met Boythorn, l think it is reasonable to assume he won’t budge either. Now there is something else to watch for in the future.

It’s worth reading the conversation between Tulkinghorn and Lady Dedlock very carefully. Yes, be on the watch.

Thoughts

Why might Lady Dedlock be so insistent on learning as much as possible about Nemo?

Equally, why might Tulkinghorn seem less that forthcoming about what he knows and what he might suspect?

Let's do a close look at how Dickens ends this chapter: “what each would give to know how much the other knows - all this is hidden, for the time, in their own hearts.” What secrets might Tulkinghorn and Lady Dedlock be keeping from each other?

Dickens epigraph “On the Watch” is, indeed, something to consider very carefully. What did you find or observe on your watch of this chapter?

On the Watch

The epigraph for this chapter in “On the Watch.” I wonder if that means we as readers should be on the watch for something or someone, or if a character in the chapter is on the watch for something or someone? Perhaps it is both those possibilities. Let’s take a look.

The chapter begins with Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock leaving France and returning to England. Apparently, Lady Dedlock is totally bored with Paris and will be less bored at home. For his part, when Sir Leicester is bored, we are told that “when he has nothing else to do, he can always contemplate his own greatness.” A party is planned and so we find Chesney Wold in preparation as some rather important English friends including Tulkinghorn are expected. We also learn that Tulkinghorn has something to tell Lady Dedlock.

Mrs Rouncewell welcomes the Dedlock’s home. Lady Dedlock spots a servant named Rosa, and bids Mrs Rouncewell and her new associate to approach. Lady Dedlock compliments Rosa on her beauty and learns that Rosa is 19 years old. In a curious turn of phrase Lady Dedlock tells Rosa to “take care they don’t spoil you by flattery.” That night Mrs Rouncewell muses that it is “almost a pity” that Lady Dedlock does not have a daughter.

We learn that Lady Dedlock has a French maid who is 32 years old. Her name is Hortense and her description is a bit unsettling. Words such as “feline mouth,” and “jaws too eager,” as well as the fact that when she is in an “ill humour and near knives” Hortense is something “like a very neat She-Wolf imperfectly tamed.” Now, that’s not a person most of us would feel comfortable around. Why would Lady Dedlock hire someone like Hortense attend her? That is something to be on the watch for in the future. Next, Dickens goes into a long list of ridiculous names of men who are connected to Parliament and are attending the party. I think it fair to say that Dickens’s opinion of Parliamentarians is rather low.

To me, the key part of this chapter is the extremely interesting interplay between Lady Dedlock and Tulkinghorn. First, we learn that Tulkinghorn has his own exclusive room in Chesney Wold. Lady Dedlock waits, and waits, for him to arrive. Finally, he “appears.” Interesting word “appears.” What does that word suggest to you? Tulkinghorn explains the reason for his late arrival is because he was engaged with “several suits between yourself and Boythorn.” Sir Leicester refuses to budge from his position. Having met Boythorn, l think it is reasonable to assume he won’t budge either. Now there is something else to watch for in the future.

It’s worth reading the conversation between Tulkinghorn and Lady Dedlock very carefully. Yes, be on the watch.

Thoughts

Why might Lady Dedlock be so insistent on learning as much as possible about Nemo?

Equally, why might Tulkinghorn seem less that forthcoming about what he knows and what he might suspect?

Let's do a close look at how Dickens ends this chapter: “what each would give to know how much the other knows - all this is hidden, for the time, in their own hearts.” What secrets might Tulkinghorn and Lady Dedlock be keeping from each other?

Dickens epigraph “On the Watch” is, indeed, something to consider very carefully. What did you find or observe on your watch of this chapter?

Chapter 13

Esther’s Narrative

In this chapter we turn, once again, to Esther’s narrative. Are you finding the transitions between the two points of view confusing? Do you find this structural approach interesting, informative, more insightful, or simply annoying?

Our chapter opens with Esther recounting the progress that has been made in deciding on an occupation for Richard. Mr Jarndyce sees Richard’s seeming uncertainty as connected in some way to Chancery. We learn that Richard had spent 8 years in a public school (private school in North American terminology) the result of which he was quite proficient in Latin verse but not much else. I think it fair to say that Richard is feckless towards his future and his “off-hand manner” seems to support that notion.

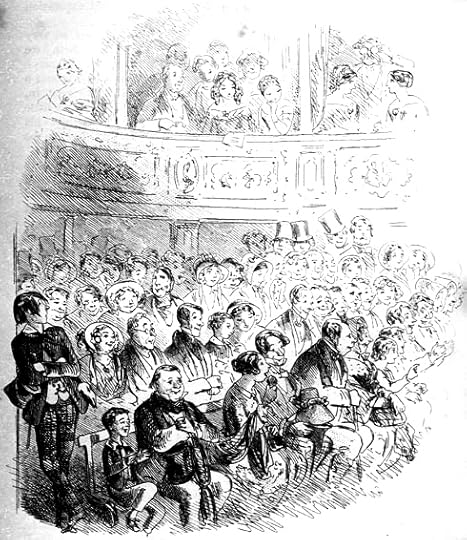

Mr Jarndyce, Esther, Richard, and Ada travel to London and one of the many activities they pursue is attending the theatre. Sadly for Esther, she spots Mr Guppy at the theatre as well. Each following trip to theatre finds Guppy in attendance as well. Esther finds these events very upsetting. Here we pause to take a look at Esther’s reaction. She tells us that she will not go to the back of the theatre box because Richard and Ada rely on her for their best conversations, and that if she tells Mr Jarndyce it might mean Guppy would lose his position. Esther dismisses her thought that she should write to Guppy’s mother, but Esther rejects that thought as well. Esther’s final decision is to do nothing. It becomes apparent to Esther that Guppy is following her in the streets and even hanging about her lodgings. That’s not funny. It is stalking, and yet Esther persisted in doing nothing. What is your opinion of Esther’s (in)actions? Of Guppy’s fervent attentions?

The matter of Richard’s occupation and association with Mr Badger comes next. The following paragraphs are examples of Dickens’s famed digressions and delightful characterizations. Mr Badger is Mrs Badger’s third husband but she spends the evening praising her first two husbands who have passed away. Mr Badger enables her flights of memory. One one level, these paragraphs seem to make little sense beyond some comic relief. I wonder, however, if there is not something else, more subtle, occurring.

Thoughts

In many ways this novel, so far, has been about the past. Questions of Esther’s past, the pasts of Ada and Richard, the never-ending court case of Jarndyce, the mystery of the Ghost’s Walk, the origins of the author of the handwriting that has raised Lady Dedlock’s curiosity, the mounds of paper that Krook guards so jealously are, among others, questions and examples of the past still present in characters’ lives. In this chapter we have Mrs Badger recalling the past. What might this all mean? Where is Dickens heading do you think?

Mary Lou among others helps us trace the possible sub-meanings of various character’s surnames. In my annotations I have just come across the following “Jarndyce - Darn nice.” I have no idea, thinking about the past in my own copy of the novel, where that came from. There is a part of my own past with the novel that remains a mystery.

The next part of the chapter finds Ada making a confession about her cousin Richard. Ada tells Esther that Richard loves her, which is not a surprise at all. It does, however, reinforce the naive nature of Ada. Esther tells Ada that she is sure cousin John is aware of their feelings as well. Jarndyce then has a fatherly chat with Richard and Ada where he dispenses good, solid, mature advice. I found a tinge of doubt in his words directed towards Richard, not so much about his present feelings, but rather towards what the future might bring. Dickens wrote as Ada and Richard leave “so they passed away into the shadow, and were gone. It was only a burst of light that had been so radiant. The room darkened as they went out, and the sun clouded over.” What do these words suggest to you? Before the chapter ends Esther comments that at the Badger’s dinner party there was a gentleman who was “rather reserved, but I thought him very sensible and agreeable. At least, Ada asked me if I did not, and I said yes.” Now why would Dickens add such a seemingly inconsequential couple of sentences to the end of this chapter?

Thoughts

We have Esther being stocked by Guppy in London, Mrs Badger - with Mr Badger’s full compliance - talking about former husband’s, and Ada and Richard making their love publicly known. This could be seen as a chapter presenting various types of love and attraction. How much love is in the air in this chapter?

Esther’s Narrative

In this chapter we turn, once again, to Esther’s narrative. Are you finding the transitions between the two points of view confusing? Do you find this structural approach interesting, informative, more insightful, or simply annoying?

Our chapter opens with Esther recounting the progress that has been made in deciding on an occupation for Richard. Mr Jarndyce sees Richard’s seeming uncertainty as connected in some way to Chancery. We learn that Richard had spent 8 years in a public school (private school in North American terminology) the result of which he was quite proficient in Latin verse but not much else. I think it fair to say that Richard is feckless towards his future and his “off-hand manner” seems to support that notion.

Mr Jarndyce, Esther, Richard, and Ada travel to London and one of the many activities they pursue is attending the theatre. Sadly for Esther, she spots Mr Guppy at the theatre as well. Each following trip to theatre finds Guppy in attendance as well. Esther finds these events very upsetting. Here we pause to take a look at Esther’s reaction. She tells us that she will not go to the back of the theatre box because Richard and Ada rely on her for their best conversations, and that if she tells Mr Jarndyce it might mean Guppy would lose his position. Esther dismisses her thought that she should write to Guppy’s mother, but Esther rejects that thought as well. Esther’s final decision is to do nothing. It becomes apparent to Esther that Guppy is following her in the streets and even hanging about her lodgings. That’s not funny. It is stalking, and yet Esther persisted in doing nothing. What is your opinion of Esther’s (in)actions? Of Guppy’s fervent attentions?

The matter of Richard’s occupation and association with Mr Badger comes next. The following paragraphs are examples of Dickens’s famed digressions and delightful characterizations. Mr Badger is Mrs Badger’s third husband but she spends the evening praising her first two husbands who have passed away. Mr Badger enables her flights of memory. One one level, these paragraphs seem to make little sense beyond some comic relief. I wonder, however, if there is not something else, more subtle, occurring.

Thoughts

In many ways this novel, so far, has been about the past. Questions of Esther’s past, the pasts of Ada and Richard, the never-ending court case of Jarndyce, the mystery of the Ghost’s Walk, the origins of the author of the handwriting that has raised Lady Dedlock’s curiosity, the mounds of paper that Krook guards so jealously are, among others, questions and examples of the past still present in characters’ lives. In this chapter we have Mrs Badger recalling the past. What might this all mean? Where is Dickens heading do you think?

Mary Lou among others helps us trace the possible sub-meanings of various character’s surnames. In my annotations I have just come across the following “Jarndyce - Darn nice.” I have no idea, thinking about the past in my own copy of the novel, where that came from. There is a part of my own past with the novel that remains a mystery.

The next part of the chapter finds Ada making a confession about her cousin Richard. Ada tells Esther that Richard loves her, which is not a surprise at all. It does, however, reinforce the naive nature of Ada. Esther tells Ada that she is sure cousin John is aware of their feelings as well. Jarndyce then has a fatherly chat with Richard and Ada where he dispenses good, solid, mature advice. I found a tinge of doubt in his words directed towards Richard, not so much about his present feelings, but rather towards what the future might bring. Dickens wrote as Ada and Richard leave “so they passed away into the shadow, and were gone. It was only a burst of light that had been so radiant. The room darkened as they went out, and the sun clouded over.” What do these words suggest to you? Before the chapter ends Esther comments that at the Badger’s dinner party there was a gentleman who was “rather reserved, but I thought him very sensible and agreeable. At least, Ada asked me if I did not, and I said yes.” Now why would Dickens add such a seemingly inconsequential couple of sentences to the end of this chapter?

Thoughts

We have Esther being stocked by Guppy in London, Mrs Badger - with Mr Badger’s full compliance - talking about former husband’s, and Ada and Richard making their love publicly known. This could be seen as a chapter presenting various types of love and attraction. How much love is in the air in this chapter?

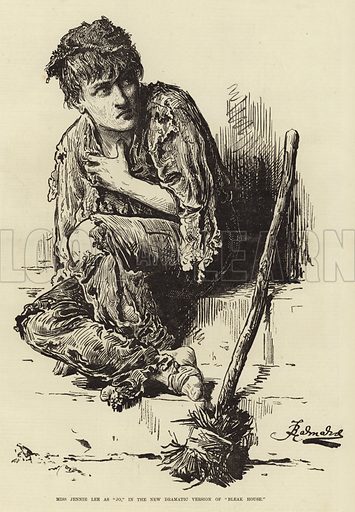

I didn't have anything to add about chapter 11, but you asked what we thought about the title. I thought "our dear brother" referred to Nemo in a brotherhood of man sort of way. Jo, of course, represents "the least of these."

I didn't have anything to add about chapter 11, but you asked what we thought about the title. I thought "our dear brother" referred to Nemo in a brotherhood of man sort of way. Jo, of course, represents "the least of these."Interesting that Nemo got his opium from a doctor. It's like all those celebrities who died on prescription drugs.

It was way more usual to get opium from a doctor in these times, it was in practically every kind of medicine in these times. It was used as painkillers like we now use paracetamol or ibuprofen f.i., and in laudanum against anything that would make you a nervous wreck, in cough syrup ... So perhaps it started as a prescription for, say, a chronic back ache from all the writing, and then it became a heroin addiction.

It is clear that Lady Dedlock wants her interest in Nemo to appear as the usual Victorian hang for dreadful stories. I don't buy it, and neither does Tulkinhorn I think. Sir Dedlock does, he is probably already happy that there at least is something of interest to his wife. Also, I keep wondering how on earth Dickens was so good at describing what I from my own experience recognize as depression in Lady Dedlock. Also, in what way would she herself have been 'spoiled by flattery'? Would she mean spoiled in a way that we nowadays say children can be spoiled brats? Or, I realised reading it this time, would she mean like food is spoiled when it is contaminated in a way? In that case there could be a connection to the Ghost Walk, at least in the eyes of the Victorian readers.

Tbh, I took the tender heart of Guster as a given. She has had a rough life and put up walls, but to me it's made pretty clear in how she adores the Snagsby's parlor, and is overwhelmed by the stationery shop. Now Mrs. Snagsby is one who I do not believe has a tender heart, but that's a whole different story.

Guppy starts to be a total creep now. Horrible to be in Esther's shoes, I am sure, but from our point of view it is pretty funny. He has a whole concrete wall in front of his head, it seems, in realising he only enstranges Esther more this way. With Guppy I always have to think about a song by another Dutch comedian, who sings about 'I have such a hard life, everything is so difficult to me!' and who then pulls out examples that make you think 'Oh, you sweet summer child ...' just as I said about Guppy earlier xD Here it is a very well known song, and it happens a lot that if someone thinks someone else in a conversation is whining about something small, to start singing 'Ik heb een heeeeeel zwaaaaar leveeeeeeeen!' ('I have a veeeeery haaaaard liiiiiiife!') and it's instantly clear what you mean. Really, I hear the song every time Guppy comes into view ...

Tbh, I took the tender heart of Guster as a given. She has had a rough life and put up walls, but to me it's made pretty clear in how she adores the Snagsby's parlor, and is overwhelmed by the stationery shop. Now Mrs. Snagsby is one who I do not believe has a tender heart, but that's a whole different story.

Guppy starts to be a total creep now. Horrible to be in Esther's shoes, I am sure, but from our point of view it is pretty funny. He has a whole concrete wall in front of his head, it seems, in realising he only enstranges Esther more this way. With Guppy I always have to think about a song by another Dutch comedian, who sings about 'I have such a hard life, everything is so difficult to me!' and who then pulls out examples that make you think 'Oh, you sweet summer child ...' just as I said about Guppy earlier xD Here it is a very well known song, and it happens a lot that if someone thinks someone else in a conversation is whining about something small, to start singing 'Ik heb een heeeeeel zwaaaaar leveeeeeeeen!' ('I have a veeeeery haaaaard liiiiiiife!') and it's instantly clear what you mean. Really, I hear the song every time Guppy comes into view ...

Peter wrote: "Chapter 12

Peter wrote: "Chapter 12On the Watch..."

This chapter, with all its Noodles and Doodles, Huffys and Puffys, and talk of "dandyism" got a bit tedious for me in parts. (Dickens, by the way, was said to be a bit of a dandy, himself, if I remember correctly. I imagine he was invited to lots of parties like these once he attained fame.)

And I'm completely over my Lady's boredom. I find myself wanting to recreate that famous scene in "Moonstruck" in which Cher slaps Nicholas Cage and says, "Snap out of it!"

But two things seem to jar my Lady out of her (and my) tedium. First, of course, is the handwriting on the legal documents. You commented on Nemo's age, Peter, and why that might be important. I went back and looked up Lady Dedlock's age, and this is what I found...

Sir Leicester is twenty years, full measure, older than my Lady. He will never see sixty-five again, nor perhaps sixty-six, nor yet sixty-seven.

The other thing that my Lady has shown a spark of interest in is Rosa -- much to Hortense's chagrin. There's a woman one wouldn't want to cross! Interesting how the two things that Lady Dedlock has shown interest in have been carefully noted by two people who, from their descriptions, may not be her allies, despite being in her employ. Is it merely because she shows interest in so little that they're taken aback by it, or is it something more?

Peter wrote: "Chapter 13..."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 13..."Oh, Guppy. I think back to my blooming adolescence, when I'd like a boy and change my route to class so that I could pass by his locker, in the hope that being visible would somehow make him realize I was around, available, and desirable. It never worked for me, and I can see that it's not going to work for Guppy, either. Especially when he starts watching her house at night, which crosses the line from immature to just plain creepy. Surely one or more of the others has noticed his omnipresence?

Peter wrote..."Now why would Dickens add such a seemingly inconsequential couple of sentences to the end of this chapter?

.... How much love is in the air in this chapter?..."

Well, I think you've answered the first question with the 2nd, and vice versa. Dickens, technically speaking, didn't add those sentences; Esther did. And while Guppy seems to wear his heart on his sleeve, Esther, who considers herself unworthy, hesitates to let anyone know of her attraction to the young surgeon, but she just can't quite keep it to herself. Soon she'll be doodling his name in hearts. :-)

I AM reminded in this chapter just how young our Three Musketeers are. They are lucky to have John Jarndyce. Peter's observation that his advice to Richard was "good, solid, and mature" is true. The court of Chancery did one good thing by making Jarndyce their guardian.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 12

On the Watch..."

This chapter, with all its Noodles and Doodles, Huffys and Puffys, and talk of "dandyism" got a bit tedious for me in parts. (Dickens, by the way, was sai..."

Hi Mary Lou

Good question about Lady Dedlock and her seemingly very limited interests. Yes indeed. I think that any information held by someone who is not a friend of Lady Dedlock is information we as readers need to consider very important as well.

On the Watch..."

This chapter, with all its Noodles and Doodles, Huffys and Puffys, and talk of "dandyism" got a bit tedious for me in parts. (Dickens, by the way, was sai..."

Hi Mary Lou

Good question about Lady Dedlock and her seemingly very limited interests. Yes indeed. I think that any information held by someone who is not a friend of Lady Dedlock is information we as readers need to consider very important as well.

Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens be so specific about the dead man’s age?"

Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens be so specific about the dead man’s age?"That didn't strike me as so odd. Esther is pretty specific about Jarndyce's age, and the narrator is pretty specific about the Deadlocks' and whats-is-name the blunderbuss guy's age as well. Isn't it just one of the things you notice about a person?

What I thought was a little weirder was the long digression about the women who might have loved him, but maybe that is less strange than sad:

If this forlorn man could have been prophetically seen lying here by the mother at whose breast he nestled, a little child, with eyes upraised to her loving face, and soft hand scarcely knowing how to close upon the neck to which it crept, what an impossibility the vision would have seemed! Oh, if in brighter days the now-extinguished fire within him ever burned for one woman who held him in her heart, where is she, while these ashes are above the ground!

Peter wrote: We learn that Lady Dedlock has a French maid who is 32 years old. Her name is Hortense and her description is a bit unsettling. Words such as “feline mouth,” and “jaws too eager,” as well as the fact that when she is in an “ill humour and near knives” Hortense is something “like a very neat She-Wolf imperfectly tamed.” Now, that’s not a person most of us would feel comfortable around. Why would Lady Dedlock hire someone like Hortense attend her? That is something to be on the watch for in the future.

Yes, she's very creepy. Kind of like David Copperfield's Rosa Dartle (not to be confused with this book's Rosa-from-town) except gratuitously so--as in Rosa had reason to be messed up but this woman is just a cat-wolf. Look out Rosa-from-town!

Mary Lou wrote: "Well, I think you've answered the first question with the 2nd, and vice versa. Dickens, technically speaking, didn't add those sentences; Esther did. And while Guppy seems to wear his heart on his sleeve, Esther, who considers herself unworthy, hesitates to let anyone know of her attraction to the young surgeon, but she just can't quite keep it to herself. Soon she'll be doodling his name in hearts. :-)"

Mary Lou wrote: "Well, I think you've answered the first question with the 2nd, and vice versa. Dickens, technically speaking, didn't add those sentences; Esther did. And while Guppy seems to wear his heart on his sleeve, Esther, who considers herself unworthy, hesitates to let anyone know of her attraction to the young surgeon, but she just can't quite keep it to herself. Soon she'll be doodling his name in hearts. :-)"Yes, I was also thinking love interest here. And I guess here we have a drawback of a Victorian young-lady narrator--not allowed to say or notice she's in love.

Still, I suppose we will SOMEHOW manage to notice it even when she can't, just as Esther SOMEHOW notices Ada and Richard before they do.

Is this the same doctor who took charge at Nemo's deathbed when the doctor Miss Flite summoned preferred to return to his dinner? They're both dark young surgeons. I will assume they're both tall dark handsome young surgeons. ;)

This book is fun. So far Tulkinghorn is my favorite though it will not surprise me at all if he ends up the villain.

This book is fun. So far Tulkinghorn is my favorite though it will not surprise me at all if he ends up the villain.

Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Well, I think you've answered the first question with the 2nd, and vice versa. Dickens, technically speaking, didn't add those sentences; Esther did. And while Guppy seems to wear ..."

Hi Julie

Yes. Same surgeon. In the background I hear violins. I wonder if there will be a red rose in the future?

Hi Julie

Yes. Same surgeon. In the background I hear violins. I wonder if there will be a red rose in the future?

Julie wrote: "What I thought was a little weirder was the long digression about the women who might have loved him, but maybe that is less strange than sad"

That part struck me too. This man must have been loved once. And if he indeed was in a better place when he was younger, just as Esther's Dark, Tall, Handsome Surgeon expects, then he might very well have been loved fiercely by a woman. What would have happened to her, and what made him fall into this state after they split up or in any way got separated? We might never know ...

That part struck me too. This man must have been loved once. And if he indeed was in a better place when he was younger, just as Esther's Dark, Tall, Handsome Surgeon expects, then he might very well have been loved fiercely by a woman. What would have happened to her, and what made him fall into this state after they split up or in any way got separated? We might never know ...

My twopence on Chapter 11: First of all, I thought it quite stunning that it was a direct sequel to Chapter 10. One may argue that Dickens did it for the sake of providing a cliff-hanger, but there may be more to it, namely the fact that for the previous instalment Dickens had run out of space, and yet he deemed the description of Nemo's death and the events appertaining to it worthy of more room. It is quite interesting that Tulkinghorn seems to hover near the portmanteau and that he incites the people around him to search for any scraps of paper that might throw light onto the identity of the recently deceased man. Alas, he is thwarted in this. But did you notice that Mr. Krook, when he is alone in the room with the corpse for a short while, his long fingers hovering like vampire's hands over the body of the dead man, finds time to slink to the portmanteau and back? May not that be a reason why later, nothing of interest was found in that often-mentioned piece of furniture? We have already learned of Krook's tendency to collect all sorts of documents, haven't we? Doubtless, we ought to keep an eye on Krook - and not because he is such a handsome man.

It's also interesting that although Jo was rejected as a witness by the coroner, both that eminent man and Mr. Tulkinghorn set aside some time to ask the boy some further questions after the inquest.

The title of the Chapter is a very bitter choice, meant to highlight the fact that people whom we might find reason to regard as our brothers and sisters perish in anonymous squalor every day around us without really making us, as society, feel ashamed of this. Mr. Snagsby is an exception to this general callousness: I was delighted to find him give half-a-crown to Jo, because obviously, the boy's condition moved him to pity.

It's also interesting that although Jo was rejected as a witness by the coroner, both that eminent man and Mr. Tulkinghorn set aside some time to ask the boy some further questions after the inquest.

The title of the Chapter is a very bitter choice, meant to highlight the fact that people whom we might find reason to regard as our brothers and sisters perish in anonymous squalor every day around us without really making us, as society, feel ashamed of this. Mr. Snagsby is an exception to this general callousness: I was delighted to find him give half-a-crown to Jo, because obviously, the boy's condition moved him to pity.

Chapter 12 is full of mysterious hints - aside from the rather long-winded excursion on contemporary Dandyism. Mr. Tulkinghorn is a master of psychological torture: In his note to Lady Dedlock, he only says that he has seen the law-writer that kindled her curiosity, but he carefully avoids any mention of the law-writer's death. From the note, Lady Dedlock would have had to imply that Mr. Tulkinghorn must have had the opportunity to talk with the man, and so she must have wondered what the man might have had to say. It is quite relentless in him to let the lady stew in her own grease that way, and he must have a reason for it.

We also get this from our omniscient narrator:

"He wears his usual expressionless mask—if it be a mask —and carries family secrets in every limb of his body and every crease of his dress. Whether his whole soul is devoted to the great or whether he yields them nothing beyond the services he sells is his personal secret. He keeps it, as he keeps the secrets of his clients; he is his own client in that matter, and will never betray himself."

What are Mr. Tulkinghorn's motives? Is he really selflessy loyal to his clients? Does he somehow play his own hand all along? Questions, questions, questions.

Lady Dedlock's interest in Rosa not only fills Hortense's mind with rancour, but it also made me ask myself whether she might not see herself in that young woman. Jantine already mentioned the lady's warning to Rosa not to allow them to spoil her by flattery because of her beauty, and I asked myself exactly the same question as Jantine did. Apart from that, there is Mrs. Rouncewell tamely complaining about the lady's lack of empathy and human kindness and saying that she might have become a more caring woman if she had ever had a daughter. Might she come to regard Rosa as a proxy for a daughter? If so, how will Hortense react?

Did you notice that the light throws a bend-sinister on her lady's portrait? In my annotations it is said that a bend-sinister is a sign in heraldry that denotes illegitimacy. The bend-sinister seems to rend the hearth in two. Just a coincidence?

We also get this from our omniscient narrator:

"He wears his usual expressionless mask—if it be a mask —and carries family secrets in every limb of his body and every crease of his dress. Whether his whole soul is devoted to the great or whether he yields them nothing beyond the services he sells is his personal secret. He keeps it, as he keeps the secrets of his clients; he is his own client in that matter, and will never betray himself."

What are Mr. Tulkinghorn's motives? Is he really selflessy loyal to his clients? Does he somehow play his own hand all along? Questions, questions, questions.

Lady Dedlock's interest in Rosa not only fills Hortense's mind with rancour, but it also made me ask myself whether she might not see herself in that young woman. Jantine already mentioned the lady's warning to Rosa not to allow them to spoil her by flattery because of her beauty, and I asked myself exactly the same question as Jantine did. Apart from that, there is Mrs. Rouncewell tamely complaining about the lady's lack of empathy and human kindness and saying that she might have become a more caring woman if she had ever had a daughter. Might she come to regard Rosa as a proxy for a daughter? If so, how will Hortense react?

Did you notice that the light throws a bend-sinister on her lady's portrait? In my annotations it is said that a bend-sinister is a sign in heraldry that denotes illegitimacy. The bend-sinister seems to rend the hearth in two. Just a coincidence?

Tristram wrote: "Did you notice that the light throws a bend-sinister on her lady's portrait? In my annotations it is said that a bend-sinister is a sign in heraldry that denotes illegitimacy. The bend-sinister seems to rend the hearth in two. Just a coincidence?"

Oh wow, I totally missed that, every time!

Oh wow, I totally missed that, every time!

The broad-bend sinister comes in a paragraph that starts out and hums with sunlight in almost sentence. Clear, cold sunshine and then kind of like — boom — there is this sinister word.

The broad-bend sinister comes in a paragraph that starts out and hums with sunlight in almost sentence. Clear, cold sunshine and then kind of like — boom — there is this sinister word.I am thankful that my edition has annotations, as I would not have known what this three part word is. The annotation makes clear that Dickens wants the reader to notice.

I also noted, which gave me a chuckle, that my annotation said this is a “proleptic” thing. I had to find out the definition of proleptic to understand the annotation.

The broad-bent sinister is a hint I missed. We are accumulating quite the list of clues to one of the main mysteries of the novel. Who is Esther, and what is her background?

The broad-bent sinister, like Krook’s bags of hair, are examples of how modern readers are at a slight disadvantage from the novel’s original readers who would more easily recognize their world and its objects. There is much discussion of Krook’s shop, bricklayers, and filth in BH. One book I found very helpful is Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth. It recounts the story of a filthy London that would be easily understood by its 19C inhabitants. You would be surprised how bricks were made and how bricks can be seen as a metaphor in BH. I highly recommend it.

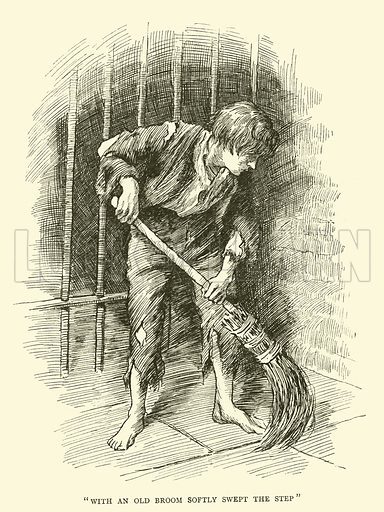

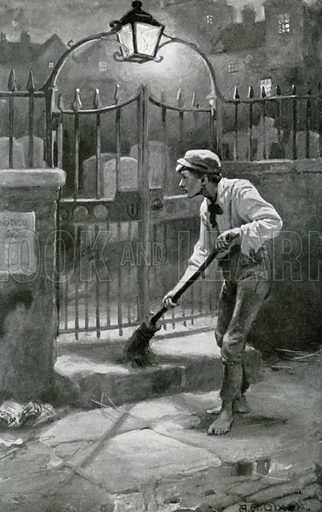

One anecdote in Jackson’s fascinating book is the fact that the crossing sweeper who kept the pavement clear by Dickens’s Tavistock House was fed from Dickens’s house. Also, Dickens arranged for the boy to be schooled in the evenings. In time, Dickens helped the boy emigrate to Australia.

The broad-bent sinister, like Krook’s bags of hair, are examples of how modern readers are at a slight disadvantage from the novel’s original readers who would more easily recognize their world and its objects. There is much discussion of Krook’s shop, bricklayers, and filth in BH. One book I found very helpful is Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth. It recounts the story of a filthy London that would be easily understood by its 19C inhabitants. You would be surprised how bricks were made and how bricks can be seen as a metaphor in BH. I highly recommend it.

One anecdote in Jackson’s fascinating book is the fact that the crossing sweeper who kept the pavement clear by Dickens’s Tavistock House was fed from Dickens’s house. Also, Dickens arranged for the boy to be schooled in the evenings. In time, Dickens helped the boy emigrate to Australia.

Peter wrote: "The broad-bent sinister is a hint I missed. We are accumulating quite the list of clues to one of the main mysteries of the novel. Who is Esther, and what is her background?

Peter wrote: "The broad-bent sinister is a hint I missed. We are accumulating quite the list of clues to one of the main mysteries of the novel. Who is Esther, and what is her background?The broad-bent siniste..."

Peter, one thing I find interesting about Bleak House is that it literally creates itself from the very first chapter as a mystery. From what I have read, at least in historical terms, the idea of a book as a mystery is something Dickens created as a new art form.

John wrote: "Peter wrote: "The broad-bent sinister is a hint I missed. We are accumulating quite the list of clues to one of the main mysteries of the novel. Who is Esther, and what is her background?

The broa..."

Hi John

Yes. I find BH contains many mysteries as well as having the first detective that Dickens incorporates as well. I often wonder how much Dickens was influenced by Edgar Allen Poe when they met during the first American reading tour of Dickens.

The broa..."

Hi John

Yes. I find BH contains many mysteries as well as having the first detective that Dickens incorporates as well. I often wonder how much Dickens was influenced by Edgar Allen Poe when they met during the first American reading tour of Dickens.

From: Finding Mr. Poe: Intertextuality and Periodicity between Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens

Edgar Allan Poe is remembered as an eccentric loner, a poet, and a writer of gothic “tales.” He earned his living (albeit a meagre one) as a journalist, writing more literary criticism than poems or tales. As a critic, he quickly gained the nick-name of “the man with the tomahawk,” a racist epithet but one which was meant to make light of his cutting negative critiques, for which his reviews became popular for giving. From 1835 until his death in 1849, Poe wrote approximately one thousand critical pieces and defined the American “standard for book reviewing.” In these pieces Poe criticised many American newspapers for “puffing” second–rate American books simply because they were American, and he identified himself as being one of the first American fans of Charles Dickens when he reviewed Sketches by Boz in June of 1836. Poe had never heard of Dickens (or Boz) prior to his review (Sketches was Dickens’s first collection, so few readers knew of him), and Poe wrote of Dickens: “we know nothing more than that he is a far more pungent, more witty, and better disciplined writer of sly articles, than nine-tenths of the Magazine writers in Great Britain.”

In the Saturday Evening Post, Poe went on to attempt to solve the mystery of the murder in Barnaby Rudge after having read only the first three available chapters, which he did for the most part. Through his reading and critique of Barnaby Rudge, Poe crafted the framework necessary for a finely tuned detective story which would come into his work with his character Dupin later that year. Dickens and Poe met briefly in Philadelphia on Dickens’s 1842 American tour, and there is no concrete evidence of what the two discussed (partly due to Poe’s tendency towards fabrication and Dickens’s later burning of his personal letters), but from most accounts, it is understood that the two got on very well. Poe felt the most important aspect of Barnaby was the relationship between Barnaby and Grip. In Poe’s first review of the available chapters of Barnaby he wrote of Barnaby and Grip that:

[Grip’s] croakings are to be frequently, appropriately, and prophetically heard in the coarse of the narrative, and whose whole character will perform, in regard to that of the idiot [Barnaby], much the same part as does, in music, the accompaniment in respect to the air. Each is distinct. Each differs remarkably from the other…This is clearly the design of Mr. Dickens although he himself may not at present perceive it.

This relationship between Barnaby and Grip is revisited in “The Raven” and Poe picks up where he felt Dickens left off; Poe’s raven is the answer to the questions that the narrator of the poem poses and the echo of his deeper self.

Before he had “The Tell-Tale Heart” published in The Pioneer in 1843, he was taken with Dickens’s Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840) and reviewed the collection favourably in 1841. He specified that of all the tales held within Humphrey, “A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second” was the most “power[ful].” He wrote, “The other stories are brief…The narrative of ‘The Bowyer,’ as well as of ‘John Podgers,’ is not altogether worthy of Mr. Dickens. They were probably sent to press to supply a demand for copy…But the ‘Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second’ is a paper of remarkable power, truly original in conception, and worked out with great ability.”

Many are not aware of this lesser known Dickens piece, as the way in which we currently read The Old Curiosity Shop is not in its original serialised form within Humphrey, therefore, the short stories which come between the larger texts (Curiosity Shop and Barnaby) are lost for most modern readers. To summarise the story, a retired soldier finds himself the adoptive father of his nephew, whose eyes and gaze he fears for an inexplicable reason. Ultimately, the narrator becomes so overwhelmed with this little boy’s gaze that he is driven to murder him and bury his body in the garden. Friends of the narrator come to call, and he entertains them with food and drink upon the very spot the boy is buried. The denouement is that a neighbour’s errant bloodhounds enter the party having sniffed out the boy’s remains, and dig up the body in front of the narrator and his guests, thus exposing his evil deed. The narrator ends his piece by stating he is writing this account while sitting in jail awaiting his execution.

Modern-day readers will be more aware of the plot of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” in which he explores the mind of a killer who becomes obsessed with “the evil eye” of a perceived oppressor. After killing the old man with which he lives, the also unnamed narrator buries him under the floorboards of their shared house, invites investigating police officers in and offers them refreshments on the very spot the old man is buried. His undoing is that the narrator continues to hear the beating of the old man’s heart and also believes the police officers hear the beating as well, and are ignoring it in order to make “a mockery of [his] horror.”

“The Tell-Tale Heart” was extremely well received by both its American and British readers; it was a “sensation.” Reviewing it for the New York Tribune in July 1843, Horace Greeley (the founder and editor of the Tribune) noted it “a strong and skilful, but to our minds overstrained and repulsive, analysis of the feelings and promptings of an insane homicide.” The success of “The Tell-Tale Heart” is due in part to the extent to which Poe utilized the then undefined Freudian term “uncanny,” but also to the powers of Poe’s editorial skills: his talents at seeing how to best manipulate a plot into a “tale.” As well, it is due to a seed planted by Dickens in his early work with Master Humphrey’s Clock, which we can trace back through Poe’s thoroughly written reviews of Dickens’s works. Poe “tomahawked” most every writer in his reviews, but he never once had a negative word to say about any of Dickens’s pieces. Re-reading “Confession” through the eyes of Poe, we can see how deeply Dickens was interested in the psyche of a madman at this early point in his career, and that he sought to explain the motives of a killer. Poe was undoubtedly paying tribute to Dickens with “The Tell-Tale Heart,” but he does so in a way that gives a rebirth to Dickens’s work and allows for a new interpretation to emerge, chiefly that Dickens’s “Confession” is one of the first pieces in which an author sought to explain the “why-done-it” as opposed to the “who-done-it” of horror stories.

Edgar Allan Poe is remembered as an eccentric loner, a poet, and a writer of gothic “tales.” He earned his living (albeit a meagre one) as a journalist, writing more literary criticism than poems or tales. As a critic, he quickly gained the nick-name of “the man with the tomahawk,” a racist epithet but one which was meant to make light of his cutting negative critiques, for which his reviews became popular for giving. From 1835 until his death in 1849, Poe wrote approximately one thousand critical pieces and defined the American “standard for book reviewing.” In these pieces Poe criticised many American newspapers for “puffing” second–rate American books simply because they were American, and he identified himself as being one of the first American fans of Charles Dickens when he reviewed Sketches by Boz in June of 1836. Poe had never heard of Dickens (or Boz) prior to his review (Sketches was Dickens’s first collection, so few readers knew of him), and Poe wrote of Dickens: “we know nothing more than that he is a far more pungent, more witty, and better disciplined writer of sly articles, than nine-tenths of the Magazine writers in Great Britain.”

In the Saturday Evening Post, Poe went on to attempt to solve the mystery of the murder in Barnaby Rudge after having read only the first three available chapters, which he did for the most part. Through his reading and critique of Barnaby Rudge, Poe crafted the framework necessary for a finely tuned detective story which would come into his work with his character Dupin later that year. Dickens and Poe met briefly in Philadelphia on Dickens’s 1842 American tour, and there is no concrete evidence of what the two discussed (partly due to Poe’s tendency towards fabrication and Dickens’s later burning of his personal letters), but from most accounts, it is understood that the two got on very well. Poe felt the most important aspect of Barnaby was the relationship between Barnaby and Grip. In Poe’s first review of the available chapters of Barnaby he wrote of Barnaby and Grip that:

[Grip’s] croakings are to be frequently, appropriately, and prophetically heard in the coarse of the narrative, and whose whole character will perform, in regard to that of the idiot [Barnaby], much the same part as does, in music, the accompaniment in respect to the air. Each is distinct. Each differs remarkably from the other…This is clearly the design of Mr. Dickens although he himself may not at present perceive it.

This relationship between Barnaby and Grip is revisited in “The Raven” and Poe picks up where he felt Dickens left off; Poe’s raven is the answer to the questions that the narrator of the poem poses and the echo of his deeper self.

Before he had “The Tell-Tale Heart” published in The Pioneer in 1843, he was taken with Dickens’s Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840) and reviewed the collection favourably in 1841. He specified that of all the tales held within Humphrey, “A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second” was the most “power[ful].” He wrote, “The other stories are brief…The narrative of ‘The Bowyer,’ as well as of ‘John Podgers,’ is not altogether worthy of Mr. Dickens. They were probably sent to press to supply a demand for copy…But the ‘Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second’ is a paper of remarkable power, truly original in conception, and worked out with great ability.”

Many are not aware of this lesser known Dickens piece, as the way in which we currently read The Old Curiosity Shop is not in its original serialised form within Humphrey, therefore, the short stories which come between the larger texts (Curiosity Shop and Barnaby) are lost for most modern readers. To summarise the story, a retired soldier finds himself the adoptive father of his nephew, whose eyes and gaze he fears for an inexplicable reason. Ultimately, the narrator becomes so overwhelmed with this little boy’s gaze that he is driven to murder him and bury his body in the garden. Friends of the narrator come to call, and he entertains them with food and drink upon the very spot the boy is buried. The denouement is that a neighbour’s errant bloodhounds enter the party having sniffed out the boy’s remains, and dig up the body in front of the narrator and his guests, thus exposing his evil deed. The narrator ends his piece by stating he is writing this account while sitting in jail awaiting his execution.

Modern-day readers will be more aware of the plot of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” in which he explores the mind of a killer who becomes obsessed with “the evil eye” of a perceived oppressor. After killing the old man with which he lives, the also unnamed narrator buries him under the floorboards of their shared house, invites investigating police officers in and offers them refreshments on the very spot the old man is buried. His undoing is that the narrator continues to hear the beating of the old man’s heart and also believes the police officers hear the beating as well, and are ignoring it in order to make “a mockery of [his] horror.”

“The Tell-Tale Heart” was extremely well received by both its American and British readers; it was a “sensation.” Reviewing it for the New York Tribune in July 1843, Horace Greeley (the founder and editor of the Tribune) noted it “a strong and skilful, but to our minds overstrained and repulsive, analysis of the feelings and promptings of an insane homicide.” The success of “The Tell-Tale Heart” is due in part to the extent to which Poe utilized the then undefined Freudian term “uncanny,” but also to the powers of Poe’s editorial skills: his talents at seeing how to best manipulate a plot into a “tale.” As well, it is due to a seed planted by Dickens in his early work with Master Humphrey’s Clock, which we can trace back through Poe’s thoroughly written reviews of Dickens’s works. Poe “tomahawked” most every writer in his reviews, but he never once had a negative word to say about any of Dickens’s pieces. Re-reading “Confession” through the eyes of Poe, we can see how deeply Dickens was interested in the psyche of a madman at this early point in his career, and that he sought to explain the motives of a killer. Poe was undoubtedly paying tribute to Dickens with “The Tell-Tale Heart,” but he does so in a way that gives a rebirth to Dickens’s work and allows for a new interpretation to emerge, chiefly that Dickens’s “Confession” is one of the first pieces in which an author sought to explain the “why-done-it” as opposed to the “who-done-it” of horror stories.

Kim wrote: "From: Finding Mr. Poe: Intertextuality and Periodicity between Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens

Edgar Allan Poe is remembered as an eccentric loner, a poet, and a writer of gothic “tales.” He e..."

Kim

Fascinating. Thank you for the research. It is apparent that Poe was much inspired by Dickens. Poe and Dickens had very different personalities although they certainly had similar thoughts about Copyright issues.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when the two of them were together!

Edgar Allan Poe is remembered as an eccentric loner, a poet, and a writer of gothic “tales.” He e..."

Kim

Fascinating. Thank you for the research. It is apparent that Poe was much inspired by Dickens. Poe and Dickens had very different personalities although they certainly had similar thoughts about Copyright issues.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when the two of them were together!

Peter wrote: "One anecdote in Jackson’s fascinating book is the fact that the crossing sweeper who kept the pavement clear by Dickens’s Tavistock House was fed from Dickens’s house. Also, Dickens arranged for the boy to be schooled in the evenings. In time, Dickens helped the boy emigrate to Australia."

Peter wrote: "One anecdote in Jackson’s fascinating book is the fact that the crossing sweeper who kept the pavement clear by Dickens’s Tavistock House was fed from Dickens’s house. Also, Dickens arranged for the boy to be schooled in the evenings. In time, Dickens helped the boy emigrate to Australia."This makes such a nice change from hearing about how he treated his wife. Thank you. ;)

From: When Charles Dickens & Edgar Allan Poe Met, and Dickens’ Pet Raven Inspired Poe’s Poem “The Raven”

“There comes Poe with his raven,” wrote the poet James Russell Lowell in 1848, “like Barnaby Rudge, / Three-fifths of him genius and two-fifths sheer fudge.” Barnaby Rudge, as you may know, is a novel by Charles Dickens, published serially in 1841. Set during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780, the book stands as Dickens’ first historical novel and a prelude of sorts to A Tale of Two Cities. But what, you may wonder, does it have to do with Poe and “his raven”?

Quite a lot, it turns out. Poe reviewed the first four chapters of Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge for Graham’s Magazine, predicting the end of the novel and finding out later he was correct when he reviewed it again upon completion. He was particularly taken with one character: a chatty raven named Grip who accompanies the simple-minded Barnaby. Poe described the bird as “intensely amusing,” points out Atlas Obscura, and also wrote that Grip’s “croaking might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama.”

It chanced the following year the two literary greats would meet, when Poe learned of Dickens’ trip to the U.S.; he wrote to the novelist, and the two briefly exchanged letters (which you can read here). Along with Dickens on his six-month journey were his wife Catherine, his children, and Grip, his pet raven. When the two writers met in person, writes Lucinda Hawksley at the BBC, Poe “was enchanted to discover [Grip, the character] was based on Dickens’s own bird.”

Indeed Dickens’ raven, “who had an impressive vocabulary,” inspired what Dickens called the “very queer character” in Barnaby Rudge, not only with his loquaciousness, but also with his distinctively ornery personality. Dickens’ daughter Mamie described the raven as “mischievous and impudent” for its habit of biting the children and “dominating” the family’s mastiff, such that the bird was banished to the carriage house.

But Dickens—who Jonathan Lethem calls the “greatest animal novelist of all time”—loved the bird, so much that he wrote movingly and humorously of Grip’s death, and had him stuffed. (A not unusual practice for Dickens; we’ve previously featured a letter opener Dickens had made from the paw of his cat, Bob.) The remains of the historical Grip now reside in the rare book section of the Free Library of Philadelphia, “a stuffed raven” writes The Washington Post’s Raymond Lane, “about the size of a big cat.”

Of the literary Grip’s influence on Poe, Janine Pollack, head of the library’s rare books department, tells Philadelphia magazine, “It is sort of a unique moment in literature when these two great writers are sort of thinking about the same thing. You think about how much the two men were looking at each other’s work. It’s almost a collaboration without them realizing it.” But can we be sure that Dickens’ Grip, real and imagined, directly inspired Poe’s “The Raven”? “Poe knew about it,” says historian Edward Pettit, “He wrote about it. And there’s a talking raven in it. So the link seems fairly obvious to me.”

Lane adduces some clear evidence of passages in the the novel that sound very much like Poe: “At the end of the fifth chapter,” for example, “Grip makes a noise and someone asks, ‘What was that—him tapping at the door?’ Another character responds, ‘’Tis someone knocking softly at the shutter.’” Hawksley notes even more similarities. “Although there is no concrete proof,” she writes, “most Poe scholars are in agreement that the poet’s fascination with Grip was the inspiration for his 1845 poem The Raven.”

Where we often find surprising lineages of influence from author to author, it’s unusual that the connections are so direct, so personal, and so odd, as those between Poe, Dickens, and Grip the talking raven. Poe courted Dickens in 1842 “to impress the novelist,” writes Sidney Moss of Southern Illinois University, “with his worth and versatility as a critic, poet, and writer of tales,” and with the aim of establishing a literary reputation, and publishing contracts, in England.

While Dickens seemed duly impressed, and willing to help, nothing commercial came of their exchange. Instead, Dickens and his raven inspired Poe to write the most famous poem of his life, “The Raven,” for which he will be remembered forevermore.

I love our cocker spaniel more than I love most people. When she dies I cannot imagine having her dead body stuffed and sitting around here somewhere or having her paw made into a pencil. The idea is creepy. Perfect for Poe not Dickens.

“There comes Poe with his raven,” wrote the poet James Russell Lowell in 1848, “like Barnaby Rudge, / Three-fifths of him genius and two-fifths sheer fudge.” Barnaby Rudge, as you may know, is a novel by Charles Dickens, published serially in 1841. Set during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780, the book stands as Dickens’ first historical novel and a prelude of sorts to A Tale of Two Cities. But what, you may wonder, does it have to do with Poe and “his raven”?

Quite a lot, it turns out. Poe reviewed the first four chapters of Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge for Graham’s Magazine, predicting the end of the novel and finding out later he was correct when he reviewed it again upon completion. He was particularly taken with one character: a chatty raven named Grip who accompanies the simple-minded Barnaby. Poe described the bird as “intensely amusing,” points out Atlas Obscura, and also wrote that Grip’s “croaking might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama.”

It chanced the following year the two literary greats would meet, when Poe learned of Dickens’ trip to the U.S.; he wrote to the novelist, and the two briefly exchanged letters (which you can read here). Along with Dickens on his six-month journey were his wife Catherine, his children, and Grip, his pet raven. When the two writers met in person, writes Lucinda Hawksley at the BBC, Poe “was enchanted to discover [Grip, the character] was based on Dickens’s own bird.”

Indeed Dickens’ raven, “who had an impressive vocabulary,” inspired what Dickens called the “very queer character” in Barnaby Rudge, not only with his loquaciousness, but also with his distinctively ornery personality. Dickens’ daughter Mamie described the raven as “mischievous and impudent” for its habit of biting the children and “dominating” the family’s mastiff, such that the bird was banished to the carriage house.

But Dickens—who Jonathan Lethem calls the “greatest animal novelist of all time”—loved the bird, so much that he wrote movingly and humorously of Grip’s death, and had him stuffed. (A not unusual practice for Dickens; we’ve previously featured a letter opener Dickens had made from the paw of his cat, Bob.) The remains of the historical Grip now reside in the rare book section of the Free Library of Philadelphia, “a stuffed raven” writes The Washington Post’s Raymond Lane, “about the size of a big cat.”

Of the literary Grip’s influence on Poe, Janine Pollack, head of the library’s rare books department, tells Philadelphia magazine, “It is sort of a unique moment in literature when these two great writers are sort of thinking about the same thing. You think about how much the two men were looking at each other’s work. It’s almost a collaboration without them realizing it.” But can we be sure that Dickens’ Grip, real and imagined, directly inspired Poe’s “The Raven”? “Poe knew about it,” says historian Edward Pettit, “He wrote about it. And there’s a talking raven in it. So the link seems fairly obvious to me.”

Lane adduces some clear evidence of passages in the the novel that sound very much like Poe: “At the end of the fifth chapter,” for example, “Grip makes a noise and someone asks, ‘What was that—him tapping at the door?’ Another character responds, ‘’Tis someone knocking softly at the shutter.’” Hawksley notes even more similarities. “Although there is no concrete proof,” she writes, “most Poe scholars are in agreement that the poet’s fascination with Grip was the inspiration for his 1845 poem The Raven.”

Where we often find surprising lineages of influence from author to author, it’s unusual that the connections are so direct, so personal, and so odd, as those between Poe, Dickens, and Grip the talking raven. Poe courted Dickens in 1842 “to impress the novelist,” writes Sidney Moss of Southern Illinois University, “with his worth and versatility as a critic, poet, and writer of tales,” and with the aim of establishing a literary reputation, and publishing contracts, in England.

While Dickens seemed duly impressed, and willing to help, nothing commercial came of their exchange. Instead, Dickens and his raven inspired Poe to write the most famous poem of his life, “The Raven,” for which he will be remembered forevermore.

I love our cocker spaniel more than I love most people. When she dies I cannot imagine having her dead body stuffed and sitting around here somewhere or having her paw made into a pencil. The idea is creepy. Perfect for Poe not Dickens.

Tristram wrote: "Did you notice that the light throws a bend-sinister on her lady's portrait? "

I feel like I spend half my life looking at Dickens illustrations and no, I have never noticed any light doing anything special at all. Except some of the dark plates are hard to see so I have to look for brighter dark plates. :-)

I feel like I spend half my life looking at Dickens illustrations and no, I have never noticed any light doing anything special at all. Except some of the dark plates are hard to see so I have to look for brighter dark plates. :-)

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Did you notice that the light throws a bend-sinister on her lady's portrait? "

I feel like I spend half my life looking at Dickens illustrations and no, I have never noticed any l..."

Kim

Since you spend half your life looking at Dickens illustrations that explains why you are perfectly content. :-)

I feel like I spend half my life looking at Dickens illustrations and no, I have never noticed any l..."

Kim

Since you spend half your life looking at Dickens illustrations that explains why you are perfectly content. :-)

This is what I want to know. Well one of them. During the chapter where we find poor Nemo dead we're told this:

"Run, Flite, run! The nearest doctor! Run!" So Mr. Krook addresses a crazy little woman who is his female lodger, who appears and vanishes in a breath, who soon returns accompanied by a testy medical man brought from his dinner, with a broad, snuffy upper lip and a broad Scotch tongue.

"Ey! Bless the hearts o' ye," says the medical man, looking up at them after a moment's examination. "He's just as dead as Phairy!"

Mr. Tulkinghorn (standing by the old portmanteau) inquires if he has been dead any time.

"Any time, sir?" says the medical gentleman. "It's probable he wull have been dead aboot three hours."

"About that time, I should say," observes a dark young man on the other side of the bed.

"Air you in the maydickle prayfession yourself, sir?" inquires the first.

The dark young man says yes.

"Then I'll just tak' my depairture," replies the other, "for I'm nae gude here!" With which remark he finishes his brief attendance and returns to finish his dinner.

The dark young surgeon passes the candle across and across the face and carefully examines the law-writer, who has established his pretensions to his name by becoming indeed No one."

Where did this guy come from?

Where did this dark young surgeon come from? Miss Flite went for a doctor and returned with the doctor, when did the other man enter the room? They couldn't have come together or the doctor would have known the dark young man. Did I miss something?

"Run, Flite, run! The nearest doctor! Run!" So Mr. Krook addresses a crazy little woman who is his female lodger, who appears and vanishes in a breath, who soon returns accompanied by a testy medical man brought from his dinner, with a broad, snuffy upper lip and a broad Scotch tongue.

"Ey! Bless the hearts o' ye," says the medical man, looking up at them after a moment's examination. "He's just as dead as Phairy!"

Mr. Tulkinghorn (standing by the old portmanteau) inquires if he has been dead any time.

"Any time, sir?" says the medical gentleman. "It's probable he wull have been dead aboot three hours."

"About that time, I should say," observes a dark young man on the other side of the bed.

"Air you in the maydickle prayfession yourself, sir?" inquires the first.

The dark young man says yes.

"Then I'll just tak' my depairture," replies the other, "for I'm nae gude here!" With which remark he finishes his brief attendance and returns to finish his dinner.

The dark young surgeon passes the candle across and across the face and carefully examines the law-writer, who has established his pretensions to his name by becoming indeed No one."

Where did this guy come from?

Where did this dark young surgeon come from? Miss Flite went for a doctor and returned with the doctor, when did the other man enter the room? They couldn't have come together or the doctor would have known the dark young man. Did I miss something?

Bored, bored, bored. I've never understood how people can be bored, there is so much to do! If I had no book to read which I can't imagine happening, I would watch TV or play the piano, or work on some craft or another, or go for a walk, or bake, or clean, there is so much to do and yet I hear all the time how bored people are. I have no sympathy for Lady Dedlock and her boredom, go get a hobby.

Peter wrote: "Since you spend half your life looking at Dickens illustrations that explains why you are perfectly content. :-)

.."

I needed all the Dickens and his illustrations I could get this past year. In fact I could have used a tiny bit of boredom. :-)

.."

I needed all the Dickens and his illustrations I could get this past year. In fact I could have used a tiny bit of boredom. :-)

Tristram wrote: "Doubtless, we ought to keep an eye on Krook - and not because he is such a handsome man."

I don't want to keep an eye on someone who collects bones and hair.

I don't want to keep an eye on someone who collects bones and hair.

Peter wrote: "I think it fair to say that Richard is feckless towards his future and his “off-hand manner” ..."

Yes, I agree. My favorite part in this chapter is:

"He had been adapted to the verses and had learnt the art of making them to such perfection that if he had remained at school until he was of age, I suppose he could only have gone on making them over and over again unless he had enlarged his education by forgetting how to do it."

Yes, I agree. My favorite part in this chapter is:

"He had been adapted to the verses and had learnt the art of making them to such perfection that if he had remained at school until he was of age, I suppose he could only have gone on making them over and over again unless he had enlarged his education by forgetting how to do it."

Poor Richard, or poor us. When picking a profession of course he can't, he wants to join the Navy, then he doesn't, he wants to join the Army, then he doesn't, he wants to become a clerk because he is fond of boating, whatever that means. Finally Mr. Jarndyce mentions a surgeon and Richard insists that is what he wants to do. I have a feeling he doesn't. Unless they are fond of swimming or some such thing.

In the notes in my edition it says: "As a surgeon, this doctor treated bodily ills and injuries. Because surgeons performed a form of manual labor, they ranked below physicians. Physicians treated mainly internal disorders and prescribed various types of physic." It still seems to me that both would be treating bodily ills and injuries wherever on the body they happen to be. Certainly, say if someone fell and broke their leg and you ran for a doctor, on coming to a physician first you wouldn't keep going because it was a bodily ill and injury. I can hear it now "Oh no! that's not a surgeon it's a physician! We have to keep going!

Well, I think a physician wouldn't be of any more help setting a bone than an apothecary or dietician would be. Basically the surgeon was the real doctor, in those times, but since that involved blood and gore, it was seen as less than the guy who bled people and prescribed them mixtures of arsenic and thyme ...

About Jo:

From: Rescuing George Ruby or Charles Dickens and the Crossing Sweeper:

There were two real Jos. The first was an orphan boy Dickens encountered in the winter of 1852 when he visited the "ragged school" in Farringdon for "Household Words". The boy, never named, had "burning cheeks and great gaunt eager eyes", and he was clutching a bottle of medicine that he had been given at a hospital too crowded to take him in. He was close to death, and, when he was lead off to the workhouse, he seemed to Dickens to slip away into the night as if going to his grave. But the second real Jo did have a name, and his name was George Ruby. Early in 1850 a case of assault was tried at Guildhall before an Alderman Humphery. Two men were charged with a vicious attack on a policeman, having been identified not only by the victim, but also by George Ruby. He had been taking some supper to his father, who was working in a warehouse, at the early hour of three in the morning. When George was put in the witness box he was handed a copy of the Bible. Seeing the boy's bewilderment, Alderman Humphery asked him if he knew what an oath was, and what he was holding. He answered "no" to both questions. Shocked by these admissions, Humphery quizzed him further. "Can you read?" "No." "Do you ever say your prayers?" "No." "Do you know what prayers are?" "No." "Do you know what the Devil is?" "I've heard of the Devil, but I don't know him." Finally, Humphery asked George what he did know, in response to which he said that he knew how to sweep the crossing. "And that's all?" "That's all. I sweeps the crossing."

The incident was widely reported in the newspapers, and, when it emerged that the Alderman had refused to hear the boy's evidence, on the grounds that he did not understand what it was to be under oath, there was a great deal of tut-tutting. "The Examiner" pointed out that, although the boy had not known that he was obliged to tell the truth, he still told the truth every time he answered "no" to the Alderman's questions.

As it happens, Dickens was working for "The Examiner" at the time, and it is quite possible that he wrote the article. He might have also written a similar piece in "Household Words" a few weeks later. At all events, he took a deep interest in the trial, which found its fictional counterpart in the inquest into Nemo's death in Bleak House.

In about 1910, some forty years after his death, one of his sons, Alfred, embarked on a tour of England, giving lectures on the life and work of his father. He had recently returned from Australia, where he had been living since 1865. At the start of one of these lectures, he related an anecdote that involved a crossing sweep.

According to Alfred, the sweep had worked at a street crossing near the family home in Tavistock Square. Alfred would have been a boy at the time, but he remembered that the sweep had appeared about a year before Bleak House was written. The sweep was young, about fourteen, and may have played a part in the creation of Jo. Dickens did more than write about his crossing sweeper. He befriended the boy, and, satisfied that he was honest, invited him into the house to eat in the kitchen. Dickens sent the boy to the Ragged School, and from there to the Shoeblack Society. Dickens sweep was kitted out with a smart red coat, and equipped with a blacking brush, and was happily earning his keep. The other redcoats knew him affectionately as "Smike".

Alfred Dickens told his audience that his father had in the end helped the young sweep - George Ruby? - emigrate to Australia. The boy went out with a "substantial outfit" that Dickens had paid for out of his own pocket. And from there he sent Dickens a letter. In that letter he thanked the great man for his kindness.

From: Rescuing George Ruby or Charles Dickens and the Crossing Sweeper:

There were two real Jos. The first was an orphan boy Dickens encountered in the winter of 1852 when he visited the "ragged school" in Farringdon for "Household Words". The boy, never named, had "burning cheeks and great gaunt eager eyes", and he was clutching a bottle of medicine that he had been given at a hospital too crowded to take him in. He was close to death, and, when he was lead off to the workhouse, he seemed to Dickens to slip away into the night as if going to his grave. But the second real Jo did have a name, and his name was George Ruby. Early in 1850 a case of assault was tried at Guildhall before an Alderman Humphery. Two men were charged with a vicious attack on a policeman, having been identified not only by the victim, but also by George Ruby. He had been taking some supper to his father, who was working in a warehouse, at the early hour of three in the morning. When George was put in the witness box he was handed a copy of the Bible. Seeing the boy's bewilderment, Alderman Humphery asked him if he knew what an oath was, and what he was holding. He answered "no" to both questions. Shocked by these admissions, Humphery quizzed him further. "Can you read?" "No." "Do you ever say your prayers?" "No." "Do you know what prayers are?" "No." "Do you know what the Devil is?" "I've heard of the Devil, but I don't know him." Finally, Humphery asked George what he did know, in response to which he said that he knew how to sweep the crossing. "And that's all?" "That's all. I sweeps the crossing."

The incident was widely reported in the newspapers, and, when it emerged that the Alderman had refused to hear the boy's evidence, on the grounds that he did not understand what it was to be under oath, there was a great deal of tut-tutting. "The Examiner" pointed out that, although the boy had not known that he was obliged to tell the truth, he still told the truth every time he answered "no" to the Alderman's questions.

As it happens, Dickens was working for "The Examiner" at the time, and it is quite possible that he wrote the article. He might have also written a similar piece in "Household Words" a few weeks later. At all events, he took a deep interest in the trial, which found its fictional counterpart in the inquest into Nemo's death in Bleak House.

In about 1910, some forty years after his death, one of his sons, Alfred, embarked on a tour of England, giving lectures on the life and work of his father. He had recently returned from Australia, where he had been living since 1865. At the start of one of these lectures, he related an anecdote that involved a crossing sweep.

According to Alfred, the sweep had worked at a street crossing near the family home in Tavistock Square. Alfred would have been a boy at the time, but he remembered that the sweep had appeared about a year before Bleak House was written. The sweep was young, about fourteen, and may have played a part in the creation of Jo. Dickens did more than write about his crossing sweeper. He befriended the boy, and, satisfied that he was honest, invited him into the house to eat in the kitchen. Dickens sent the boy to the Ragged School, and from there to the Shoeblack Society. Dickens sweep was kitted out with a smart red coat, and equipped with a blacking brush, and was happily earning his keep. The other redcoats knew him affectionately as "Smike".

Alfred Dickens told his audience that his father had in the end helped the young sweep - George Ruby? - emigrate to Australia. The boy went out with a "substantial outfit" that Dickens had paid for out of his own pocket. And from there he sent Dickens a letter. In that letter he thanked the great man for his kindness.

Jantine wrote: "Well, I think a physician wouldn't be of any more help setting a bone than an apothecary or dietician would be. Basically the surgeon was the real doctor, in those times, but since that involved bl..."

Say, how are you doing over there? I saw rioting in the Netherlands on TV last night.

Say, how are you doing over there? I saw rioting in the Netherlands on TV last night.

I'm doing fine, personally. There's no rioting in my city, although the stories from other places are terrifying. In the town between here and my parents' village they have to stay indoors all day now, in a couple of neighbourhoods, because of the riots. In Veenendaal of all places, who would have guessed ... the world has gone mad.

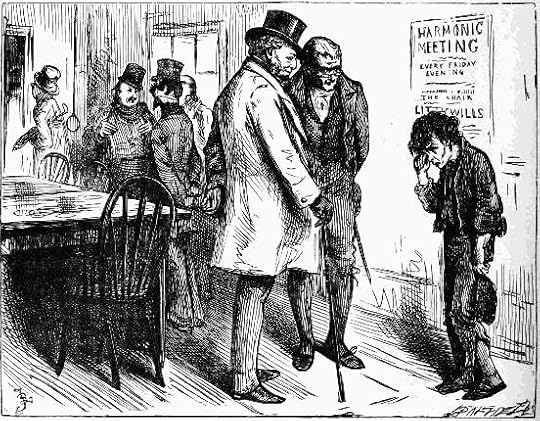

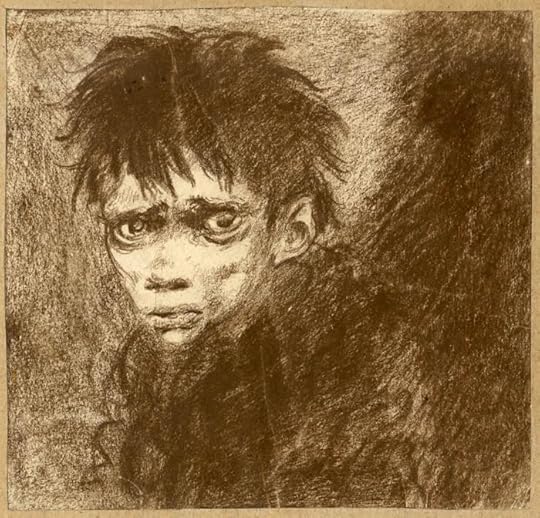

Mr. Guppy's desolation

Chapter 13

Phiz

Text Illustrated: