The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Bleak House

Bleak House

>

Bleak House, Chp. 17-19

Chapter 18 is titled "Lady Dedlock" but we begin the chapter with Richard, at first still unable to decide between law and medicine for a career. I don't think Richard is very good at deciding when it comes to him having to actually get a job. Finally at midsummer he leaves Mr. Badger and begins an experimental course with Kenge and Carboy. He promises to be in earnest this time but Mr. Jarndyce now finds the wind always in the east. Me too. They now find for him a neat little furnished lodging in a quiet old house near Queen Square and Richard immediately spends all the money he has on furnishing his new home. Esther tells us:

"He immediately began to spend all the money he had in buying the oddest little ornaments and luxuries for this lodging; and so often as Ada and I dissuaded him from making any purchase that he had in contemplation which was particularly unnecessary and expensive, he took credit for what it would have cost and made out that to spend anything less on something else was to save the difference."

I'm glad I don't think of money the way Richard does, it's too confusing. Now that Richard is as settled as he gets, they go for a visit to Mr. Boythorn's unfortunately taking Skimpole with them. I don't know why Mr. Boythorn invited him, but he did. Esther tells us they had a pleasant journey down into Lincolnshire by the coach and had an entertaining companion in Mr. Skimpole. I just can't figure out what is so entertaining about him. I do not like this guy at all, he doesn't seem like such a child to me, after all, he is married apparently and has children. So he must have been a little bit of an adult a night here and there. And where are they when he spends all his time drifting from place to place eating the food paid for by other people, sleeping in their beds, where is his family? Ah, if I think too much about Mr. Skimpole I run the risk of becoming grumpy so I'll leave him to the rest of you for now.

I found it interesting to compare the descriptions of Chesney Wold, the first is from the second chapter when Lady Dedlock was there and bored:

"My Lady Dedlock's place has been extremely dreary. The weather for many a day and night has been so wet that the trees seem wet through, and the soft loppings and prunings of the woodman's axe can make no crash or crackle as they fall. The deer, looking soaked, leave quagmires where they pass. The shot of a rifle loses its sharpness in the moist air, and its smoke moves in a tardy little cloud towards the green rise, coppice-topped, that makes a background for the falling rain. The view from my Lady Dedlock's own windows is alternately a lead-coloured view and a view in Indian ink. The vases on the stone terrace in the foreground catch the rain all day; and the heavy drops fall—drip, drip, drip—upon the broad flagged pavement, called from old time the Ghost's Walk, all night."

Now that Esther, Ada, Mr. Jarndyce and Mr. Skimpole are seeing it for the first time, Esther describes it this way:

"It was a picturesque old house in a fine park richly wooded. Among the trees and not far from the residence he pointed out the spire of the little church of which he had spoken. Oh, the solemn woods over which the light and shadow travelled swiftly, as if heavenly wings were sweeping on benignant errands through the summer air; the smooth green slopes, the glittering water, the garden where the flowers were so symmetrically arranged in clusters of the richest colours, how beautiful they looked! The house, with gable and chimney, and tower, and turret, and dark doorway, and broad terrace-walk, twining among the balustrades of which, and lying heaped upon the vases, there was one great flush of roses, seemed scarcely real in its light solidity and in the serene and peaceful hush that rested on all around it. To Ada and to me, that above all appeared the pervading influence. On everything, house, garden, terrace, green slopes, water, old oaks, fern, moss, woods again, and far away across the openings in the prospect to the distance lying wide before us with a purple bloom upon it, there seemed to be such undisturbed repose."

It makes me feel sorry for Lady Dedlock but I'm not sure why. Mr. Boythorn's house is described as a very pretty house, with cherry trees and apple trees heavy with fruit, raspberries, strawberries, peaches, cucumbers, my only problem with the entire thing was I don't think all these different fruits, vegetables, not to mention the flowers, would be ripe at the same time.

Sunday morning they attend church and among the people there Esther notices the pretty girl who is a servant of Lady Dedlock and another girl who Esther did not find agreeable for though she also was handsome, she seemed "maliciously watchful of this pretty girl, and indeed of everyone and everything there. Finally she sees Lady Dedlock:

"Shall I ever forget the rapid beating at my heart, occasioned by the look I met as I stood up! Shall I ever forget the manner in which those handsome proud eyes seemed to spring out of their languor and to hold mine! It was only a moment before I cast mine down—released again, if I may say so—on my book; but I knew the beautiful face quite well in that short space of time.

And, very strangely, there was something quickened within me, associated with the lonely days at my godmother's; yes, away even to the days when I had stood on tiptoe to dress myself at my little glass after dressing my doll. And this, although I had never seen this lady's face before in all my life—I was quite sure of it—absolutely certain."

Hmm, something quickened inside of her? Something about Lady Dedlock reminded her of her godmother, and of her days as a child looking in the mirror. She says she knew the face quite well. Ok, now I'm thinking if Esther's godmother is her aunt, and Lady Dedlock reminds her of her godmother, than Lady Dedlock should be either another aunt or what I'm betting on, Esther's mother. So if I now think that Lady Dedlock is her mother and earlier Mr. Jarndyce looked troubled when she said he was a father to her, were Mr. Jarndyce and Lady Dedlock once lovers? I can't imagine it. I'm still thinking though. This six degrees of separation thing is getting confusing. Then there's the dead guy she just had to go see. And the secret only Mr. Tulkinghorn knows, or is trying to figure out. I'm still thinking.

And finally, the next Saturday Esther, Ada and Mr. Jarndyce are out in the woods sitting at a favorite place when it starts raining and they take shelter in a nearby keeper's lodge. They find that Lady Dedlock has already taken shelter there and when Esther hears her voice this happens:

"The beating of my heart came back again. I had never heard the voice, as I had never seen the face, but it affected me in the same strange way. Again, in a moment, there arose before my mind innumerable pictures of myself."

Lady Dedlock is introduced to Ada and Esther, but when she is introduced to Esther she quickly turns away. She also asks Mr. Jarndyce if he knew her sister when they were abroad, and he says that he did. Lady Dedlock then says she and her sister have gone their separate ways. When the carriage arrives for Lady Dedlock, both the pretty girl and the Frenchwoman are in it. When Lady Dedlock asks why the have both come and Hortense says that she is her maid for the present. Lady Dedlock, however, makes it clear that she had requested only the young girl. She gets in the carriage taking Rosa with her and leaving Hortense still standing there. I think Hortense is going to be trouble, this is the end of the chapter:

"I suppose there is nothing pride can so little bear with as pride itself, and that she was punished for her imperious manner. Her retaliation was the most singular I could have imagined. She remained perfectly still until the carriage had turned into the drive, and then, without the least discomposure of countenance, slipped off her shoes, left them on the ground, and walked deliberately in the same direction through the wettest of the wet grass.

"Is that young woman mad?" said my guardian.

"Oh, no, sir!" said the keeper, who, with his wife, was looking after her. "Hortense is not one of that sort. She has as good a head-piece as the best. But she's mortal high and passionate—powerful high and passionate; and what with having notice to leave, and having others put above her, she don't take kindly to it."

"But why should she walk shoeless through all that water?" said my guardian.

"Why, indeed, sir, unless it is to cool her down!" said the man.

"Or unless she fancies it's blood," said the woman. "She'd as soon walk through that as anything else, I think, when her own's up!"

We passed not far from the house a few minutes afterwards. Peaceful as it had looked when we first saw it, it looked even more so now, with a diamond spray glittering all about it, a light wind blowing, the birds no longer hushed but singing strongly, everything refreshed by the late rain, and the little carriage shining at the doorway like a fairy carriage made of silver. Still, very steadfastly and quietly walking towards it, a peaceful figure too in the landscape, went Mademoiselle Hortense, shoeless, through the wet grass.

"He immediately began to spend all the money he had in buying the oddest little ornaments and luxuries for this lodging; and so often as Ada and I dissuaded him from making any purchase that he had in contemplation which was particularly unnecessary and expensive, he took credit for what it would have cost and made out that to spend anything less on something else was to save the difference."

I'm glad I don't think of money the way Richard does, it's too confusing. Now that Richard is as settled as he gets, they go for a visit to Mr. Boythorn's unfortunately taking Skimpole with them. I don't know why Mr. Boythorn invited him, but he did. Esther tells us they had a pleasant journey down into Lincolnshire by the coach and had an entertaining companion in Mr. Skimpole. I just can't figure out what is so entertaining about him. I do not like this guy at all, he doesn't seem like such a child to me, after all, he is married apparently and has children. So he must have been a little bit of an adult a night here and there. And where are they when he spends all his time drifting from place to place eating the food paid for by other people, sleeping in their beds, where is his family? Ah, if I think too much about Mr. Skimpole I run the risk of becoming grumpy so I'll leave him to the rest of you for now.

I found it interesting to compare the descriptions of Chesney Wold, the first is from the second chapter when Lady Dedlock was there and bored:

"My Lady Dedlock's place has been extremely dreary. The weather for many a day and night has been so wet that the trees seem wet through, and the soft loppings and prunings of the woodman's axe can make no crash or crackle as they fall. The deer, looking soaked, leave quagmires where they pass. The shot of a rifle loses its sharpness in the moist air, and its smoke moves in a tardy little cloud towards the green rise, coppice-topped, that makes a background for the falling rain. The view from my Lady Dedlock's own windows is alternately a lead-coloured view and a view in Indian ink. The vases on the stone terrace in the foreground catch the rain all day; and the heavy drops fall—drip, drip, drip—upon the broad flagged pavement, called from old time the Ghost's Walk, all night."

Now that Esther, Ada, Mr. Jarndyce and Mr. Skimpole are seeing it for the first time, Esther describes it this way:

"It was a picturesque old house in a fine park richly wooded. Among the trees and not far from the residence he pointed out the spire of the little church of which he had spoken. Oh, the solemn woods over which the light and shadow travelled swiftly, as if heavenly wings were sweeping on benignant errands through the summer air; the smooth green slopes, the glittering water, the garden where the flowers were so symmetrically arranged in clusters of the richest colours, how beautiful they looked! The house, with gable and chimney, and tower, and turret, and dark doorway, and broad terrace-walk, twining among the balustrades of which, and lying heaped upon the vases, there was one great flush of roses, seemed scarcely real in its light solidity and in the serene and peaceful hush that rested on all around it. To Ada and to me, that above all appeared the pervading influence. On everything, house, garden, terrace, green slopes, water, old oaks, fern, moss, woods again, and far away across the openings in the prospect to the distance lying wide before us with a purple bloom upon it, there seemed to be such undisturbed repose."

It makes me feel sorry for Lady Dedlock but I'm not sure why. Mr. Boythorn's house is described as a very pretty house, with cherry trees and apple trees heavy with fruit, raspberries, strawberries, peaches, cucumbers, my only problem with the entire thing was I don't think all these different fruits, vegetables, not to mention the flowers, would be ripe at the same time.

Sunday morning they attend church and among the people there Esther notices the pretty girl who is a servant of Lady Dedlock and another girl who Esther did not find agreeable for though she also was handsome, she seemed "maliciously watchful of this pretty girl, and indeed of everyone and everything there. Finally she sees Lady Dedlock:

"Shall I ever forget the rapid beating at my heart, occasioned by the look I met as I stood up! Shall I ever forget the manner in which those handsome proud eyes seemed to spring out of their languor and to hold mine! It was only a moment before I cast mine down—released again, if I may say so—on my book; but I knew the beautiful face quite well in that short space of time.

And, very strangely, there was something quickened within me, associated with the lonely days at my godmother's; yes, away even to the days when I had stood on tiptoe to dress myself at my little glass after dressing my doll. And this, although I had never seen this lady's face before in all my life—I was quite sure of it—absolutely certain."

Hmm, something quickened inside of her? Something about Lady Dedlock reminded her of her godmother, and of her days as a child looking in the mirror. She says she knew the face quite well. Ok, now I'm thinking if Esther's godmother is her aunt, and Lady Dedlock reminds her of her godmother, than Lady Dedlock should be either another aunt or what I'm betting on, Esther's mother. So if I now think that Lady Dedlock is her mother and earlier Mr. Jarndyce looked troubled when she said he was a father to her, were Mr. Jarndyce and Lady Dedlock once lovers? I can't imagine it. I'm still thinking though. This six degrees of separation thing is getting confusing. Then there's the dead guy she just had to go see. And the secret only Mr. Tulkinghorn knows, or is trying to figure out. I'm still thinking.

And finally, the next Saturday Esther, Ada and Mr. Jarndyce are out in the woods sitting at a favorite place when it starts raining and they take shelter in a nearby keeper's lodge. They find that Lady Dedlock has already taken shelter there and when Esther hears her voice this happens:

"The beating of my heart came back again. I had never heard the voice, as I had never seen the face, but it affected me in the same strange way. Again, in a moment, there arose before my mind innumerable pictures of myself."

Lady Dedlock is introduced to Ada and Esther, but when she is introduced to Esther she quickly turns away. She also asks Mr. Jarndyce if he knew her sister when they were abroad, and he says that he did. Lady Dedlock then says she and her sister have gone their separate ways. When the carriage arrives for Lady Dedlock, both the pretty girl and the Frenchwoman are in it. When Lady Dedlock asks why the have both come and Hortense says that she is her maid for the present. Lady Dedlock, however, makes it clear that she had requested only the young girl. She gets in the carriage taking Rosa with her and leaving Hortense still standing there. I think Hortense is going to be trouble, this is the end of the chapter:

"I suppose there is nothing pride can so little bear with as pride itself, and that she was punished for her imperious manner. Her retaliation was the most singular I could have imagined. She remained perfectly still until the carriage had turned into the drive, and then, without the least discomposure of countenance, slipped off her shoes, left them on the ground, and walked deliberately in the same direction through the wettest of the wet grass.

"Is that young woman mad?" said my guardian.

"Oh, no, sir!" said the keeper, who, with his wife, was looking after her. "Hortense is not one of that sort. She has as good a head-piece as the best. But she's mortal high and passionate—powerful high and passionate; and what with having notice to leave, and having others put above her, she don't take kindly to it."

"But why should she walk shoeless through all that water?" said my guardian.

"Why, indeed, sir, unless it is to cool her down!" said the man.

"Or unless she fancies it's blood," said the woman. "She'd as soon walk through that as anything else, I think, when her own's up!"

We passed not far from the house a few minutes afterwards. Peaceful as it had looked when we first saw it, it looked even more so now, with a diamond spray glittering all about it, a light wind blowing, the birds no longer hushed but singing strongly, everything refreshed by the late rain, and the little carriage shining at the doorway like a fairy carriage made of silver. Still, very steadfastly and quietly walking towards it, a peaceful figure too in the landscape, went Mademoiselle Hortense, shoeless, through the wet grass.

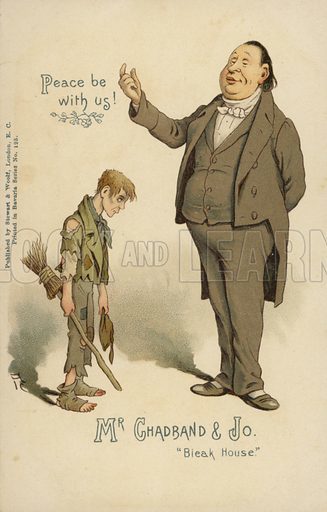

Finally for this week we have Chapter 19 which has the title "Moving On". It's easy to see why the chapter had that as the title. I only wish it would have been Mr. Chadband who was moving on. If he always talks as much as he does here I'm surprised he ever moves on. The narrator begins by describing the long vacation in Chancery Lane. It is summertime, and many courts are out of session. Everyone goes on vacation. The narrator tells us:

"The bar of England is scattered over the face of the earth. How England can get on through four long summer months without its bar—which is its acknowledged refuge in adversity and its only legitimate triumph in prosperity—is beside the question; assuredly that shield and buckler of Britannia are not in present wear.......Scarcely one is to be encountered in the deserted region of Chancery Lane. If such a lonely member of the bar do flit across the waste and come upon a prowling suitor who is unable to leave off haunting the scenes of his anxiety, they frighten one another and retreat into opposite shades."

Mr. Snagsby, the law-stationer, can now relax and this is the time when he and Mrs. Snagsby usually receive company, which I would think would take all the fun out of relaxing for a few weeks. Today Mr. and Mrs. Chadband are visiting the Snagsbys. Mr. Chadband is in the ministry although attached to no particular denomination. They are described this way:

"Mr. Chadband is a large yellow man with a fat smile and a general appearance of having a good deal of train oil in his system. Mrs. Chadband is a stern, severe-looking, silent woman. Mr. Chadband moves softly and cumbrously, not unlike a bear who has been taught to walk upright. He is very much embarrassed about the arms, as if they were inconvenient to him and he wanted to grovel, is very much in a perspiration about the head, and never speaks without first putting up his great hand, as delivering a token to his hearers that he is going to edify them."

And speak he does, in fact he rarely stops speaking and certainly must love hearing his own voice for not too many other people could. I know I would have stopped listening long ago. The first thing out of his mouth is this:

"My friends," says Mr. Chadband, "peace be on this house! On the master thereof, on the mistress thereof, on the young maidens, and on the young men! My friends, why do I wish for peace? What is peace? Is it war? No. Is it strife? No. Is it lovely, and gentle, and beautiful, and pleasant, and serene, and joyful? Oh, yes! Therefore, my friends, I wish for peace, upon you and upon yours."

Uh, whatever. I did enjoy this:

"My friends," says he, "what is this which we now behold as being spread before us? Refreshment. Do we need refreshment then, my friends? We do. And why do we need refreshment, my friends? Because we are but mortal, because we are but sinful, because we are but of the earth, because we are not of the air. Can we fly, my friends? We cannot. Why can we not fly, my friends?"

Mr. Snagsby, presuming on the success of his last point, ventures to observe in a cheerful and rather knowing tone, "No wings." But is immediately frowned down by Mrs. Snagsby."

Mr. Chadband is interrupted by the arrival of Jo being held by a constable. The constable tells Mr. Snagsby that the boy has been told he must move on but he won’t leave the area even though he has been told "five hundred times". The boy says he has nowhere to go and the constable says it is his job to move him on and his instructions don't go into where. The constable says Jo claims to know Mr. Snagsby, which Mr. Snagsby says he does, from the inquest regarding the dead man. He doesn’t reveal that he gave Jo a half-crown. At that moment, Mr. Guppy arrives and Jo is asked to explain how he got the money that was found on him. Jo says that it is the remains of a gold sovereign paid to him for showing a lady where Mr. Nemo lived, worked, and was buried. Questioning Jo, Mr. Guppy learns the entire story. Mrs. Chadband reveals to Mr. Guppy that she has known Kenge and Carboy’s office for years, because of a situation concerning a child. She explains that she was left in charge of a child named Esther Summerson. I think we have once again found Mrs. Rachel, I wonder why. And why Mr. Guppy shows up I have no idea. Mr. Guppy tells her that he was the one who met Esther when she first came to London. I don't think she really cares.

As the chapter ends Mr. Chadband can't resist giving another one of his speeches centered mainly on Jo. Finally his speech ends with him making Jo promise to come back over and over again.

"My friends," says Chadband, looking round him in conclusion, "I will not proceed with my young friend now. Will you come to-morrow, my young friend, and inquire of this good lady where I am to be found to deliver a discourse unto you, and will you come like the thirsty swallow upon the next day, and upon the day after that, and upon the day after that, and upon many pleasant days, to hear discourses?"

And now Mr. Guppy throws Jo a penny which was very nice of him, and Mr. Snagsby gives him the extra food, which was very nice of him, and Jo "moves on".

"And there he sits, munching and gnawing, and looking up at the great cross on the summit of St. Paul's Cathedral, glittering above a red-and-violet-tinted cloud of smoke. From the boy's face one might suppose that sacred emblem to be, in his eyes, the crowning confusion of the great, confused city—so golden, so high up, so far out of his reach. There he sits, the sun going down, the river running fast, the crowd flowing by him in two streams—everything moving on to some purpose and to one end—until he is stirred up and told to "move on" too."

Now I'm off to find the illustrations.

"The bar of England is scattered over the face of the earth. How England can get on through four long summer months without its bar—which is its acknowledged refuge in adversity and its only legitimate triumph in prosperity—is beside the question; assuredly that shield and buckler of Britannia are not in present wear.......Scarcely one is to be encountered in the deserted region of Chancery Lane. If such a lonely member of the bar do flit across the waste and come upon a prowling suitor who is unable to leave off haunting the scenes of his anxiety, they frighten one another and retreat into opposite shades."

Mr. Snagsby, the law-stationer, can now relax and this is the time when he and Mrs. Snagsby usually receive company, which I would think would take all the fun out of relaxing for a few weeks. Today Mr. and Mrs. Chadband are visiting the Snagsbys. Mr. Chadband is in the ministry although attached to no particular denomination. They are described this way:

"Mr. Chadband is a large yellow man with a fat smile and a general appearance of having a good deal of train oil in his system. Mrs. Chadband is a stern, severe-looking, silent woman. Mr. Chadband moves softly and cumbrously, not unlike a bear who has been taught to walk upright. He is very much embarrassed about the arms, as if they were inconvenient to him and he wanted to grovel, is very much in a perspiration about the head, and never speaks without first putting up his great hand, as delivering a token to his hearers that he is going to edify them."

And speak he does, in fact he rarely stops speaking and certainly must love hearing his own voice for not too many other people could. I know I would have stopped listening long ago. The first thing out of his mouth is this:

"My friends," says Mr. Chadband, "peace be on this house! On the master thereof, on the mistress thereof, on the young maidens, and on the young men! My friends, why do I wish for peace? What is peace? Is it war? No. Is it strife? No. Is it lovely, and gentle, and beautiful, and pleasant, and serene, and joyful? Oh, yes! Therefore, my friends, I wish for peace, upon you and upon yours."

Uh, whatever. I did enjoy this:

"My friends," says he, "what is this which we now behold as being spread before us? Refreshment. Do we need refreshment then, my friends? We do. And why do we need refreshment, my friends? Because we are but mortal, because we are but sinful, because we are but of the earth, because we are not of the air. Can we fly, my friends? We cannot. Why can we not fly, my friends?"

Mr. Snagsby, presuming on the success of his last point, ventures to observe in a cheerful and rather knowing tone, "No wings." But is immediately frowned down by Mrs. Snagsby."

Mr. Chadband is interrupted by the arrival of Jo being held by a constable. The constable tells Mr. Snagsby that the boy has been told he must move on but he won’t leave the area even though he has been told "five hundred times". The boy says he has nowhere to go and the constable says it is his job to move him on and his instructions don't go into where. The constable says Jo claims to know Mr. Snagsby, which Mr. Snagsby says he does, from the inquest regarding the dead man. He doesn’t reveal that he gave Jo a half-crown. At that moment, Mr. Guppy arrives and Jo is asked to explain how he got the money that was found on him. Jo says that it is the remains of a gold sovereign paid to him for showing a lady where Mr. Nemo lived, worked, and was buried. Questioning Jo, Mr. Guppy learns the entire story. Mrs. Chadband reveals to Mr. Guppy that she has known Kenge and Carboy’s office for years, because of a situation concerning a child. She explains that she was left in charge of a child named Esther Summerson. I think we have once again found Mrs. Rachel, I wonder why. And why Mr. Guppy shows up I have no idea. Mr. Guppy tells her that he was the one who met Esther when she first came to London. I don't think she really cares.

As the chapter ends Mr. Chadband can't resist giving another one of his speeches centered mainly on Jo. Finally his speech ends with him making Jo promise to come back over and over again.

"My friends," says Chadband, looking round him in conclusion, "I will not proceed with my young friend now. Will you come to-morrow, my young friend, and inquire of this good lady where I am to be found to deliver a discourse unto you, and will you come like the thirsty swallow upon the next day, and upon the day after that, and upon the day after that, and upon many pleasant days, to hear discourses?"

And now Mr. Guppy throws Jo a penny which was very nice of him, and Mr. Snagsby gives him the extra food, which was very nice of him, and Jo "moves on".

"And there he sits, munching and gnawing, and looking up at the great cross on the summit of St. Paul's Cathedral, glittering above a red-and-violet-tinted cloud of smoke. From the boy's face one might suppose that sacred emblem to be, in his eyes, the crowning confusion of the great, confused city—so golden, so high up, so far out of his reach. There he sits, the sun going down, the river running fast, the crowd flowing by him in two streams—everything moving on to some purpose and to one end—until he is stirred up and told to "move on" too."

Now I'm off to find the illustrations.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 17...I had to look up who Mrs. Shipton was..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 17...I had to look up who Mrs. Shipton was..."As you pointed out, there is such a wealth of endearments that the thought of looking any of them up seemed too overwhelming, and I stuck with what I know about Old Mother Hubbard. But the information about Mrs. Shipton is interesting. What are we to make of it? What prophesying has Esther done?

So, after reading that, I did a Wikipedia refresher on Minerva: "the Roman goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy...She was the virgin goddess of music, poetry, medicine, wisdom, commerce, weaving, and the crafts." Wisdom pops up twice there. And very interesting that justice and the law are under her domain, as well.

The Badgers are tedious, aren't they? It's nice that the good doctor doesn't seem at all threatened by his predecessors, I guess. Or maybe he feels completely inadequate and is just trying to beat others to the comparisons he thinks they're bound to make (think Fat Amy in Pitch Perfect, perhaps).

I still think of Richard as eager and winsome, but naïve. I can see his youthful charm. His time to grow up is running out, though, if he wants to marry Ada. Few can get by on charm alone (with the dubious exception, perhaps, of Skimpole).

If I'm interpreting the text correctly, it was Esther's cruel aunt who contacted Jarndyce. Why him, I wonder? Were they acquainted? Does he just have a reputation for being a soft touch? What brought these two together?

Kim wrote: "Chapter 18 is titled "Lady Dedlock" but we begin the chapter with Richard, at first still unable to decide between law and medicine for a career. I don't think Richard is very good at deciding when..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 18 is titled "Lady Dedlock" but we begin the chapter with Richard, at first still unable to decide between law and medicine for a career. I don't think Richard is very good at deciding when..."Kim wrote: "Chapter 18 ... I found it interesting to compare the descriptions of Chesney Wold..."

Ah, Kim - you beat me to it! I noticed, too, that Lincolnshire was a dreary, gloomy place until Esther arrived. She brings with her sunshine, lollipops, and rainbows, to quote Leslie Gore...until the day they meet my Lady, and suddenly things become tenebrous again. Dickens has set up quite a dichotomy between Esther and Lady Dedlock. Even their names - Dedlock is full of dark, negative imagery, whereas Summerson could hardly be more, well, sunny.

Kim wrote: "I'm still thinking."

There's so much here to think about.

On a frivolous note, why wouldn't Hortense walk through the rain and puddles in her bare feet? Certainly that would be preferable to wearing wet shoes all day, no? Undoubtedly something to do with Victorian propriety. Or is walking barefoot meant to symbolize something deeper? Like when Paul McCartney being barefoot on the cover of Abbey Road was a clue that he was really dead.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 19 ...I think we have once again found Mrs. Rachel"

Kim wrote: "Chapter 19 ...I think we have once again found Mrs. Rachel"I hadn't even considered Rachel! My mind went immediately to the school, where I thought the Chadbands might have been forcing their particular brand of evangelism on the students there. I enjoyed the playful interrogation between Guppy and Mrs. Chadband. Why so coy, I wonder? Was she actually flirting with Guppy?!

"O glorious to be a human boy!"

If I ever have a grandson, I'm getting a onesie with this quote printed on it. :-)

Things aren't so glorious for poor Jo, though. Hopefully if he gets roped into coming back for religious instruction, they'll continue to give him food and a bit of money to make up for the little income he's missing sweeping the streets. I notice the Chadbands didn't chip in at all when Guppy and Snagsby were doing their bit to help Jo out.

...and here we have "Dame Durden" lyrics and a youtube recording:

...and here we have "Dame Durden" lyrics and a youtube recording:https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_co...

Dame Durden kept five servant maids

To carry the milking pail;

She also kept five labouring men

To use the spade and flail.

`Twas Moll and Bet, and Doll and Kit,

And Dolly to drag her tail;

It was Tom and Dick, and Joe and Jack,

And Humphrey with his flail.

And Joe kissed Dolly, and Jack kissed Kitty,

And Humphrey with his flail;

And Kitty she was the charming girl

To carry her milking pail.

Dame Durden in the morning so soon

She did begin to call;

To rouse her servants, maids and men,

She did begin to bawl.

`Twas on the morn of Valentine

When birds began to tweet,

Dame Durden and her maids and men

They all together meet.

So Dame Durden is about bringing couples together apparently. Like Esther is the go-between for Ada and Richard, but indirectly also for Caddy and Prince. Would there be more couples who come together under her eyes?

Also, what I found very telling about Hortense, was this bit:

In what way will she be walking through blood?

Also, what I found very telling about Hortense, was this bit:

"Or unless she fancies it's blood," said the woman. "She'd as soon walk through that as anything else, I think, when her own's up!"

In what way will she be walking through blood?

Also, I am just as confused as Jo. Where should he move on to? How? Why?

Jantine wrote: "Also, I am just as confused as Jo. Where should he move on to? How? Why?"

Jantine

Your questions are perfect. That is the problem that society presents for Jo and all those disadvantaged people he represents. Where should he go? Where can he go?

All the parliamentary Doodles and Poodles have no answers and, worse, are seeking no answers.

Jantine

Your questions are perfect. That is the problem that society presents for Jo and all those disadvantaged people he represents. Where should he go? Where can he go?

All the parliamentary Doodles and Poodles have no answers and, worse, are seeking no answers.

Kim wrote: "So if I now think that Lady Dedlock is her mother and earlier Mr. Jarndyce looked troubled when she said he was a father to her, were Mr. Jarndyce and Lady Dedlock once lovers? I can't imagine it. I'm still thinking though. This six degrees of separation thing is getting confusing. "

Kim wrote: "So if I now think that Lady Dedlock is her mother and earlier Mr. Jarndyce looked troubled when she said he was a father to her, were Mr. Jarndyce and Lady Dedlock once lovers? I can't imagine it. I'm still thinking though. This six degrees of separation thing is getting confusing. "No kidding.

"Then there's the dead guy she just had to go see."

I'm betting on the dead guy with the arresting handwriting as being dad. The Jarndyce-Lady D interaction at the keeper's lodge wasn't loaded enough for it to be him. Otherwise I'd definitely think so. As it is, I can't figure out what he's up to with Esther--though I assume the reason he's outlining her parentage is because Woodcourt would court her if he could. But he's broke. And his mother's mean.

Esther tells us that she wants “to be quite candid about all I thought and did.” In some ways, I see this as somewhat similar to David Copperfield’s question of whether he will be the hero of his own narrative. Interesting positions for both the narrators and, of course, us readers. How do we respond to the first person narrator?

So far in the novel I believe what Esther is telling us. She may, at times, be rather self-effacing, but, as readers, we have the option of how much of her assertions to accept.

By my math Esther is 21 year’s old. She was raised as an orphan for 12 years and it is 9 years since Jarndyce since he received the letter. Allan Woodcourt, we are told by Esther, is 7 years older than she is. There seems to be a spark of interest between these two. This novel seems to be developing more “love” connections than earlier novels.

As to Jarndyce, he is such a kind man. Still, by surrounding himself with the likes of Jellyby, Pardiggle, and Skimpole are we to assume he is too naive? Is there meant to be a connection between the fact that the lawsuit is draining him of his wealth and many of the people he surrounds himself with seem intent on tapping his pockets in a much more intimate and immediate manner?

So far in the novel I believe what Esther is telling us. She may, at times, be rather self-effacing, but, as readers, we have the option of how much of her assertions to accept.

By my math Esther is 21 year’s old. She was raised as an orphan for 12 years and it is 9 years since Jarndyce since he received the letter. Allan Woodcourt, we are told by Esther, is 7 years older than she is. There seems to be a spark of interest between these two. This novel seems to be developing more “love” connections than earlier novels.

As to Jarndyce, he is such a kind man. Still, by surrounding himself with the likes of Jellyby, Pardiggle, and Skimpole are we to assume he is too naive? Is there meant to be a connection between the fact that the lawsuit is draining him of his wealth and many of the people he surrounds himself with seem intent on tapping his pockets in a much more intimate and immediate manner?

Mary Lou wrote: "If I'm interpreting the text correctly, it was Esther's cruel aunt who contacted Jarndyce. Why him, I wonder? Were they acquainted? Does he just have a reputation for being a soft touch? What brought these two together?"

I think that Mr. Jarndyce, what with his interactions with all those Jellybys and Pardiggles and Quayles, has attained the reputation of a philanthropist and might well be a reasonably well-known person in this quality, and that is why Mrs. Barbary (an assumed name) contacted him in order to ensure that her niece would not be quite friendless in the event of her, Mrs. Barbary's, death. Still, there is the question why the aunt would go to such lengths for a girl she does not really like at all and even considers a blot on the family name. My immediate answer to this would be that the aunt acted on a sense of duty, feeling that it would not do to expose a member of her family to poverty and all the dangers linked with it.

As to Hortense's walking barefooted through the water, I think it is to be seen in connection with what is said about her, namely that she would also walk through blood in that way. Hortense is definitely someone who might commit a crime of passion, her passion here being the green ey'd monster jealousy. In this respect, Lady Dedlock is clearly to blame, because her overt preference of Rose, which might be the whim of a spoilt lady, brings out the worse in the temperamental Frenchwoman and also places the inncocent young girl into the line of fire.

What does Lady Dedlock really see in Rosa? Herself as a younger woman? From Lady Dedlock's general behaviour, which I would consider as egocentric and self-indulgent, I'd say that this must be the case. Or does she she a daughter surrogate in the young girl? Mrs. Rouncewell's comment on the lady's childlessness might point in that direction.

I think that Mr. Jarndyce, what with his interactions with all those Jellybys and Pardiggles and Quayles, has attained the reputation of a philanthropist and might well be a reasonably well-known person in this quality, and that is why Mrs. Barbary (an assumed name) contacted him in order to ensure that her niece would not be quite friendless in the event of her, Mrs. Barbary's, death. Still, there is the question why the aunt would go to such lengths for a girl she does not really like at all and even considers a blot on the family name. My immediate answer to this would be that the aunt acted on a sense of duty, feeling that it would not do to expose a member of her family to poverty and all the dangers linked with it.

As to Hortense's walking barefooted through the water, I think it is to be seen in connection with what is said about her, namely that she would also walk through blood in that way. Hortense is definitely someone who might commit a crime of passion, her passion here being the green ey'd monster jealousy. In this respect, Lady Dedlock is clearly to blame, because her overt preference of Rose, which might be the whim of a spoilt lady, brings out the worse in the temperamental Frenchwoman and also places the inncocent young girl into the line of fire.

What does Lady Dedlock really see in Rosa? Herself as a younger woman? From Lady Dedlock's general behaviour, which I would consider as egocentric and self-indulgent, I'd say that this must be the case. Or does she she a daughter surrogate in the young girl? Mrs. Rouncewell's comment on the lady's childlessness might point in that direction.

Tristram wrote: "As to Hortense's walking barefooted through the water, I think it is to be seen in connection with what is said about her, namely that she would also walk through blood in that way. Hortense is definitely someone who might commit a crime of passion, her passion here being the green ey'd monster jealousy.."

Tristram wrote: "As to Hortense's walking barefooted through the water, I think it is to be seen in connection with what is said about her, namely that she would also walk through blood in that way. Hortense is definitely someone who might commit a crime of passion, her passion here being the green ey'd monster jealousy.."I really loved that scene. It was weird and eerie and understated and totally unexpected. Of all the things I thought Hortense might do, walking barefoot was not on the list.

Peter wrote: "As to Jarndyce, he is such a kind man. Still, by surrounding himself with the likes of Jellyby, Pardiggle, and Skimpole are we to assume he is too naive? Is there meant to be a connection between the fact that the lawsuit is draining him of his wealth and many he surrounds himself with seem intent on tapping his pockets in a much more intimate and immediate manner?"

Peter wrote: "As to Jarndyce, he is such a kind man. Still, by surrounding himself with the likes of Jellyby, Pardiggle, and Skimpole are we to assume he is too naive? Is there meant to be a connection between the fact that the lawsuit is draining him of his wealth and many he surrounds himself with seem intent on tapping his pockets in a much more intimate and immediate manner?"I don't know, but I would like to think there's some connection between Jarndyce's willingness to let others exploit him and the book's themes, because I find it very undermining of all Esther's proclamations that he is wonderful when he lets himself be played in ways that do no good to anyone. He does deserve a lot of credit for his kindness to his wards. But at this point, I am skimming all the Skimpole sections in the book. The point has been made and it's too frustrating to see it made over and over again and nobody learning anything from it.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "As to Jarndyce, he is such a kind man. Still, by surrounding himself with the likes of Jellyby, Pardiggle, and Skimpole are we to assume he is too naive? Is there meant to be a connec..."

Julie

“skimming all the Skimpole sections.” Perfect phrase.

May I join you?

Julie

“skimming all the Skimpole sections.” Perfect phrase.

May I join you?

Chapter 18 is so good on so many fronts. That the title is “Lady Dedlock” makes the chapter even more intriguing.

Richard, Skimpole, and Micawber all seem to be cut from a similar cloth. Dickens certainly has an eye for different ways one can fall into debt. Touching on Dickens’s own family’s biography, I wonder how much of his personal family experience finds itself being worked into his novels.

I’m glad Kim pointed out how Chesney Wold has now been described as both a sunny and a gloomy place. I wonder to what extent Chesney Wold reflects the people who dwell within it or come to visit it? Does Chesney Wold, like the seemingly ever-present mirrors in the novel, reflect or obscure the faces of the people who are associated with it?

The idea of faces and the presence of mirrors is carried further in this chapter. At the church, Esther comments “(s)hall I ever forget the manner in which those handsome proud eyes (referring to Lady Dedlock) seemed to spring out of their languor, and to hold mine? It was only a moment before I cast mine down - released again ... but I knew the beautiful face quite well, in that short space of time.”

And then we read when Esther reflects on her past that “with the lonely days at my godmother’s; yes, away even to the days when I stood on tiptoe to dress myself at my little glass, after dressing my doll. And this, although I had never seen the lady’s face before in all my life.” And then Esther wonders “why her face should be, in a confused way, like a broken glass to me, in which I saw scraps of old remembrances;”

I found the above lines of Esther the most powerful of the novel so far. There are so many answers that seem on the tip of our minds, and yet so many mysteries that still exist. At the centre of the questions are the references to mirrors and broken glass. Esther sees fragments of her past when she looks at Lady Dedlock. Esther says she also recalls dressing herself and her doll. We know that Esther buried her doll before she began her new life at Bleak House. Could the buried doll be seen as a symbol of Esther’s attempt to bury her past? If so, then this chapter makes it evident that the past is never really buried. We all carry our past and our present in our faces.

The past can never be returned to or escaped from. Lady Dedlock is attracted to Rosa and hopes she will never been ruined by a man. What is Lady Dedlock’s past? I think Kim is right. Lady Dedlock is Esther’s mother. Lady Dedlock’s attentions and guardianship towards Rosa is, to some extent, Lady Dedlock trying to protect a young girl from making a fatal error with a man.

As we move further and further into the novel I think it becomes increasingly important to keep our own eyes on Esther’s face, Dickens’s referrals to mirrors, and to Hablot Browne and how he positions Esther in the upcoming illustrations.

Richard, Skimpole, and Micawber all seem to be cut from a similar cloth. Dickens certainly has an eye for different ways one can fall into debt. Touching on Dickens’s own family’s biography, I wonder how much of his personal family experience finds itself being worked into his novels.

I’m glad Kim pointed out how Chesney Wold has now been described as both a sunny and a gloomy place. I wonder to what extent Chesney Wold reflects the people who dwell within it or come to visit it? Does Chesney Wold, like the seemingly ever-present mirrors in the novel, reflect or obscure the faces of the people who are associated with it?

The idea of faces and the presence of mirrors is carried further in this chapter. At the church, Esther comments “(s)hall I ever forget the manner in which those handsome proud eyes (referring to Lady Dedlock) seemed to spring out of their languor, and to hold mine? It was only a moment before I cast mine down - released again ... but I knew the beautiful face quite well, in that short space of time.”

And then we read when Esther reflects on her past that “with the lonely days at my godmother’s; yes, away even to the days when I stood on tiptoe to dress myself at my little glass, after dressing my doll. And this, although I had never seen the lady’s face before in all my life.” And then Esther wonders “why her face should be, in a confused way, like a broken glass to me, in which I saw scraps of old remembrances;”

I found the above lines of Esther the most powerful of the novel so far. There are so many answers that seem on the tip of our minds, and yet so many mysteries that still exist. At the centre of the questions are the references to mirrors and broken glass. Esther sees fragments of her past when she looks at Lady Dedlock. Esther says she also recalls dressing herself and her doll. We know that Esther buried her doll before she began her new life at Bleak House. Could the buried doll be seen as a symbol of Esther’s attempt to bury her past? If so, then this chapter makes it evident that the past is never really buried. We all carry our past and our present in our faces.

The past can never be returned to or escaped from. Lady Dedlock is attracted to Rosa and hopes she will never been ruined by a man. What is Lady Dedlock’s past? I think Kim is right. Lady Dedlock is Esther’s mother. Lady Dedlock’s attentions and guardianship towards Rosa is, to some extent, Lady Dedlock trying to protect a young girl from making a fatal error with a man.

As we move further and further into the novel I think it becomes increasingly important to keep our own eyes on Esther’s face, Dickens’s referrals to mirrors, and to Hablot Browne and how he positions Esther in the upcoming illustrations.

The mirror and the doll strike me as foreshadowing, but neither is really typically used for such.

The mirror and the doll strike me as foreshadowing, but neither is really typically used for such. I was reminded of a poem I read many years ago about a childhood doll returning on the legs the poet never thought to give it.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 18 is so good on so many fronts. That the title is “Lady Dedlock” makes the chapter even more intriguing.

Richard, Skimpole, and Micawber all seem to be cut from a similar cloth. Dickens c..."

I really hadn't given it much thought before, but in this part Esther clothes her doll like a mother would dress her child. She buried her doll (and perhaps symbolically buried her child) to start a new life. Perhaps someone else has done the same, or thought she did the same. I'm thinking of Lady Dedlock, who is, as far as we now know, childless, but who is pulled towards Rosa like the latter is a kind of substitute daughter, making remarks like 'don't let them spoil you' (which might very well refer to men and being spoilt like spoilt food if you get my drift), and she is described in a way that (and I repeat this) reminds me a lot of myself in the most depressed periods of my life.

Richard, Skimpole, and Micawber all seem to be cut from a similar cloth. Dickens c..."

I really hadn't given it much thought before, but in this part Esther clothes her doll like a mother would dress her child. She buried her doll (and perhaps symbolically buried her child) to start a new life. Perhaps someone else has done the same, or thought she did the same. I'm thinking of Lady Dedlock, who is, as far as we now know, childless, but who is pulled towards Rosa like the latter is a kind of substitute daughter, making remarks like 'don't let them spoil you' (which might very well refer to men and being spoilt like spoilt food if you get my drift), and she is described in a way that (and I repeat this) reminds me a lot of myself in the most depressed periods of my life.

Jantine wrote: "She buried her doll (and perhaps symbolically buried her child) to start a new life. Perhaps someone else has done the same, or thought she did the same. I'm thinking of Lady Dedlock, who is, as far as we now know, childless."

Jantine wrote: "She buried her doll (and perhaps symbolically buried her child) to start a new life. Perhaps someone else has done the same, or thought she did the same. I'm thinking of Lady Dedlock, who is, as far as we now know, childless."AHHHHH. This gives me chills. Esther burying her doll to move on to a new life with a new patron, just as--apparently--her mother buried her.

Jantine wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 18 is so good on so many fronts. That the title is “Lady Dedlock” makes the chapter even more intriguing.

Richard, Skimpole, and Micawber all seem to be cut from a similar cl..."

Jantine and Julie

Yes. This novel has more possible psychological depth than previous ones. Julie’s suggestion does indeed give one chills.

Richard, Skimpole, and Micawber all seem to be cut from a similar cl..."

Jantine and Julie

Yes. This novel has more possible psychological depth than previous ones. Julie’s suggestion does indeed give one chills.

I especially liked Mr. Snagsby and Mr. Guppy in Chapter 19 because both of them showed some sympathy to Jo. Mr. Chadband is an oily revenant of Mr. Stiggins from Pickwick Papers, only with the difference that Mr. Stiggins was more inclined to partaking of liquid refreshments wheras Mr. Chadband's target group is larger in that it also includes the non-liquid delicacies.

What has Mr. Guppy gathered so far? He has gathered that a certain woman has asked Jo to show him the places where a particular law-writer lived, where he got some of his work and where he was finally enterred. Does he have an idea of who that certain woman is? And why does Esther come into play here, and in what way? Dickens relies heavily on coincidence in the construction of his plots, but I think that the coincidence of Mrs. Chadband being no other than Mrs. Rachael is not so out of the way - from my own experience with coincidences, we are often thrown in with people who know people we know.

Mr. Guppy cross-examines Jo, and I think this was not only done for the sake of showing off his legal savvy to the company, but also because what Jo had to tell genuinely intrigued Mr. Guppy. I think it will be a safe bet to say that sooner or later Mr. Guppy will show up at Mr. Krook's.

What has Mr. Guppy gathered so far? He has gathered that a certain woman has asked Jo to show him the places where a particular law-writer lived, where he got some of his work and where he was finally enterred. Does he have an idea of who that certain woman is? And why does Esther come into play here, and in what way? Dickens relies heavily on coincidence in the construction of his plots, but I think that the coincidence of Mrs. Chadband being no other than Mrs. Rachael is not so out of the way - from my own experience with coincidences, we are often thrown in with people who know people we know.

Mr. Guppy cross-examines Jo, and I think this was not only done for the sake of showing off his legal savvy to the company, but also because what Jo had to tell genuinely intrigued Mr. Guppy. I think it will be a safe bet to say that sooner or later Mr. Guppy will show up at Mr. Krook's.

Caddy's Flowers

Chapter 17

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Why, Caddy, my dear," said I, "what beautiful flowers!"

She had such an exquisite little nosegay in her hand.

"Indeed, I think so, Esther," replied Caddy. "They are the loveliest I ever saw."

"Prince, my dear?" said I in a whisper.

"No," answered Caddy, shaking her head and holding them to me to smell. "Not Prince."

"Well, to be sure, Caddy!" said I. "You must have two lovers!"

"What? Do they look like that sort of thing?" said Caddy.

"Do they look like that sort of thing?" I repeated, pinching her cheek.

Caddy only laughed in return, and telling me that she had come for half an hour, at the expiration of which time Prince would be waiting for her at the corner, sat chatting with me and Ada in the window, every now and then handing me the flowers again or trying how they looked against my hair. At last, when she was going, she took me into my room and put them in my dress.

"For me?" said I, surprised.

"For you," said Caddy with a kiss. "They were left behind by somebody."

"Left behind?"

"At poor Miss Flite's," said Caddy. "Somebody who has been very good to her was hurrying away an hour ago to join a ship and left these flowers behind. No, no! Don't take them out. Let the pretty little things lie here," said Caddy, adjusting them with a careful hand, "because I was present myself, and I shouldn't wonder if somebody left them on purpose!"

I can't tell who is who:

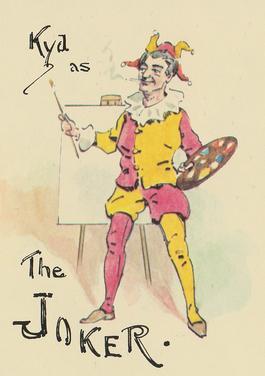

The Little Church in the Park

Chapter 18

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"The congregation was extremely small and quite a rustic one with the exception of a large muster of servants from the house, some of whom were already in their seats, while others were yet dropping in. There were some stately footmen, and there was a perfect picture of an old coachman, who looked as if he were the official representative of all the pomps and vanities that had ever been put into his coach. There was a very pretty show of young women, and above them, the handsome old face and fine responsible portly figure of the housekeeper towered pre-eminent. The pretty girl of whom Mr. Boythorn had told us was close by her. She was so very pretty that I might have known her by her beauty even if I had not seen how blushingly conscious she was of the eyes of the young fisherman, whom I discovered not far off. One face, and not an agreeable one, though it was handsome, seemed maliciously watchful of this pretty girl, and indeed of every one and everything there. It was a Frenchwoman's.

As the bell was yet ringing and the great people were not yet come, I had leisure to glance over the church, which smelt as earthy as a grave, and to think what a shady, ancient, solemn little church it was. The windows, heavily shaded by trees, admitted a subdued light that made the faces around me pale, and darkened the old brasses in the pavement and the time and damp-worn monuments, and rendered the sunshine in the little porch, where a monotonous ringer was working at the bell, inestimably bright. But a stir in that direction, a gathering of reverential awe in the rustic faces, and a blandly ferocious assumption on the part of Mr. Boythorn of being resolutely unconscious of somebody's existence forewarned me that the great people were come and that the service was going to begin.

"'Enter not into judgment with thy servant, O Lord, for in thy sight — '"

Shall I ever forget the rapid beating at my heart, occasioned by the look I met as I stood up! Shall I ever forget the manner in which those handsome proud eyes seemed to spring out of their languor and to hold mine! It was only a moment before I cast mine down — released again, if I may say so — on my book; but I knew the beautiful face quite well in that short space of time.

And, very strangely, there was something quickened within me, associated with the lonely days at my godmother's; yes, away even to the days when I had stood on tiptoe to dress myself at my little glass after dressing my doll. And this, although I had never seen this lady's face before in all my life — I was quite sure of it — absolutely certain.

It was easy to know that the ceremonious, gouty, grey-haired gentleman, the only other occupant of the great pew, was Sir Leicester Dedlock, and that the lady was Lady Dedlock. But why her face should be, in a confused way, like a broken glass to me, in which I saw scraps of old remembrances, and why I should be so fluttered and troubled (for I was still) by having casually met her eyes, I could not think."

The Little Church in the Park

Chapter 18

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"The congregation was extremely small and quite a rustic one with the exception of a large muster of servants from the house, some of whom were already in their seats, while others were yet dropping in. There were some stately footmen, and there was a perfect picture of an old coachman, who looked as if he were the official representative of all the pomps and vanities that had ever been put into his coach. There was a very pretty show of young women, and above them, the handsome old face and fine responsible portly figure of the housekeeper towered pre-eminent. The pretty girl of whom Mr. Boythorn had told us was close by her. She was so very pretty that I might have known her by her beauty even if I had not seen how blushingly conscious she was of the eyes of the young fisherman, whom I discovered not far off. One face, and not an agreeable one, though it was handsome, seemed maliciously watchful of this pretty girl, and indeed of every one and everything there. It was a Frenchwoman's.

As the bell was yet ringing and the great people were not yet come, I had leisure to glance over the church, which smelt as earthy as a grave, and to think what a shady, ancient, solemn little church it was. The windows, heavily shaded by trees, admitted a subdued light that made the faces around me pale, and darkened the old brasses in the pavement and the time and damp-worn monuments, and rendered the sunshine in the little porch, where a monotonous ringer was working at the bell, inestimably bright. But a stir in that direction, a gathering of reverential awe in the rustic faces, and a blandly ferocious assumption on the part of Mr. Boythorn of being resolutely unconscious of somebody's existence forewarned me that the great people were come and that the service was going to begin.

"'Enter not into judgment with thy servant, O Lord, for in thy sight — '"

Shall I ever forget the rapid beating at my heart, occasioned by the look I met as I stood up! Shall I ever forget the manner in which those handsome proud eyes seemed to spring out of their languor and to hold mine! It was only a moment before I cast mine down — released again, if I may say so — on my book; but I knew the beautiful face quite well in that short space of time.

And, very strangely, there was something quickened within me, associated with the lonely days at my godmother's; yes, away even to the days when I had stood on tiptoe to dress myself at my little glass after dressing my doll. And this, although I had never seen this lady's face before in all my life — I was quite sure of it — absolutely certain.

It was easy to know that the ceremonious, gouty, grey-haired gentleman, the only other occupant of the great pew, was Sir Leicester Dedlock, and that the lady was Lady Dedlock. But why her face should be, in a confused way, like a broken glass to me, in which I saw scraps of old remembrances, and why I should be so fluttered and troubled (for I was still) by having casually met her eyes, I could not think."

To my great surprise, on going in, I found my guardian still there, and sitting looking at the ashes

Chapter 17

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

I soon found myself very busy. But I had left some silk downstairs in a work-table drawer in the temporary growlery, and coming to a stop for want of it, I took my candle and went softly down to get it. To my great surprise, on going in I found my guardian still there, and sitting looking at the ashes. He was lost in thought, his book lay unheeded by his side, his silvered iron-grey hair was scattered confusedly upon his forehead as though his hand had been wandering among it while his thoughts were elsewhere, and his face looked worn. Almost frightened by coming upon him so unexpectedly, I stood still for a moment and should have retired without speaking had he not, in again passing his hand abstractedly through his hair, seen me and started.

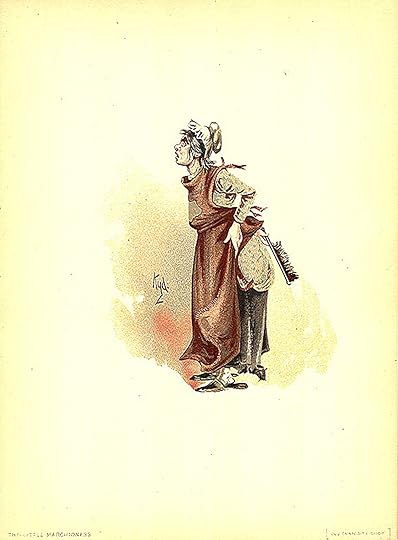

"I have frightened you!" she said

Chapter 18

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Lady Dedlock had taken shelter in the lodge before our arrival there and had come out of the gloom within. She stood behind my chair with her hand upon it. I saw her with her hand close to my shoulder when I turned my head.

"I have frightened you?" she said.

No. It was not fright. Why should I be frightened!

"I believe," said Lady Dedlock to my guardian, "I have the pleasure of speaking to Mr. Jarndyce."

"Your remembrance does me more honour than I had supposed it would, Lady Dedlock," he returned.

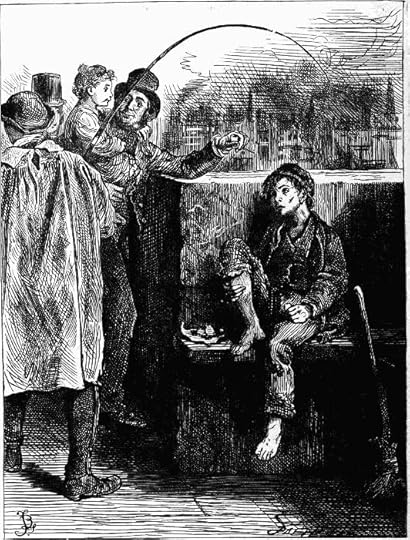

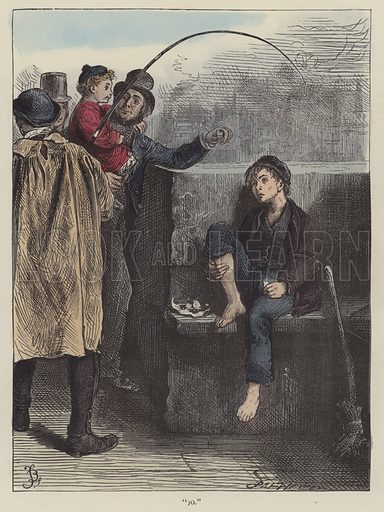

"Who ud go and let a nice innocent lodging to such a reg'lar one as me!"

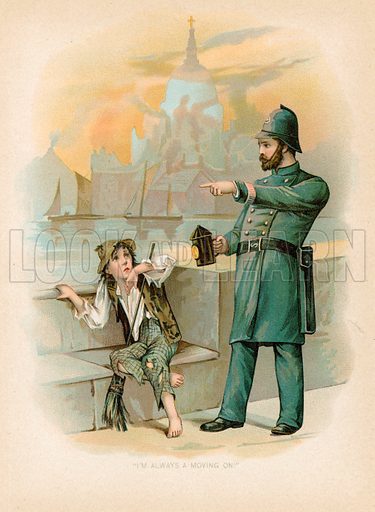

Chapter 19

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Now, I know where you live," says the constable, then, to Jo. "You live down in Tom-all-Alone's. That's a nice innocent place to live in, ain't it?"

"I can't go and live in no nicer place, sir," replies Jo. "They wouldn't have nothink to say to me if I wos to go to a nice innocent place fur to live. Who ud go and let a nice innocent lodging to such a reg'lar one as me!"

"You are very poor, ain't you?" says the constable.

"Yes, I am indeed, sir, wery poor in gin'ral," replies Jo. "I leave you to judge now! I shook these two half-crowns out of him," says the constable, producing them to the company, "in only putting my hand upon him!"

"They're wot's left, Mr. Snagsby," says Jo, "out of a sov-ring as wos give me by a lady in a wale as sed she wos a servant and as come to my crossin one night and asked to be showd this 'ere ouse and the ouse wot him as you giv the writin to died at, and the berrin-ground wot he's berrid in. She ses to me she ses 'are you the boy at the inkwhich?' she ses. I ses 'yes' I ses. She ses to me she ses 'can you show me all them places?' I ses 'yes I can' I ses. And she ses to me 'do it' and I dun it and she giv me a sov'ring and hooked it. And I an't had much of the sov'ring neither," says Jo, with dirty tears, "fur I had to pay five bob, down in Tom-all-Alone's, afore they'd square it fur to give me change, and then a young man he thieved another five while I was asleep and another boy he thieved ninepence and the landlord he stood drains round with a lot more on it."

"You don't expect anybody to believe this, about the lady and the sovereign, do you?" says the constable, eyeing him aside with ineffable disdain.

"I don't know as I do, sir," replies Jo. "I don't expect nothink at all, sir, much, but that's the true hist'ry on it."

"I'm always a moving on",

Jo in Bleak House. Illustration for Beautiful Stories about Children by Charles Dickens retold by his Granddaughter and others.

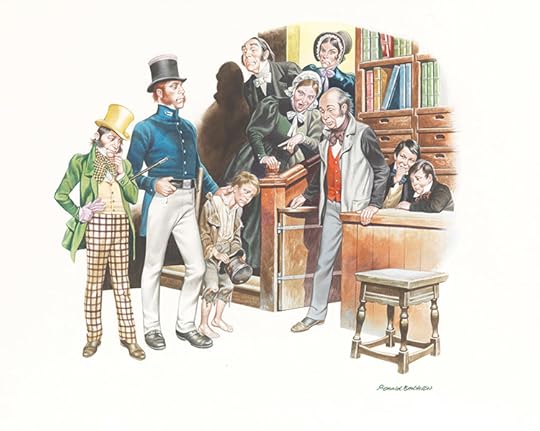

"Why, bless my heart," says Mr. Snagsby, "what's the matter!"

Chapter 19

Ron Embleton

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Snagsby descends and finds the two 'prentices intently contemplating a police constable, who holds a ragged boy by the arm.

"Why, bless my heart," says Mr. Snagsby, "what's the matter!"

"This boy," says the constable, "although he's repeatedly told to, won't move on—"

"I'm always a-moving on, sar," cries the boy, wiping away his grimy tears with his arm. "I've always been a-moving and a-moving on, ever since I was born. Where can I possibly move to, sir, more nor I do move!"

"He won't move on," says the constable calmly, with a slight professional hitch of his neck involving its better settlement in his stiff stock, "although he has been repeatedly cautioned, and therefore I am obliged to take him into custody. He's as obstinate a young gonoph as I know. He WON'T move on."

"Oh, my eye! Where can I move to!" cries the boy, clutching quite desperately at his hair and beating his bare feet upon the floor of Mr. Snagsby's passage.

"Don't you come none of that or I shall make blessed short work of you!" says the constable, giving him a passionless shake. "My instructions are that you are to move on. I have told you so five hundred times."

"But where?" cries the boy.

"Well! Really, constable, you know," says Mr. Snagsby wistfully, and coughing behind his hand his cough of great perplexity and doubt, "really, that does seem a question. Where, you know?"

"My instructions don't go to that," replies the constable. "My instructions are that this boy is to move on."

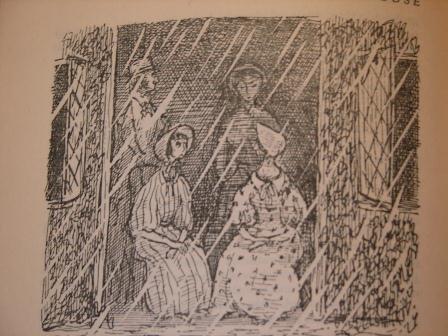

The lattice-windows were all thrown open, and we sat just within the doorway watching the storm.

Chapter 18

Edward Gorey(I think)

Text Illustrated:

The lodge was so dark within, now the sky was overcast, that we only clearly saw the man who came to the door when we took shelter there and put two chairs for Ada and me. The lattice-windows were all thrown open, and we sat just within the doorway watching the storm. It was grand to see how the wind awoke, and bent the trees, and drove the rain before it like a cloud of smoke; and to hear the solemn thunder and to see the lightning; and while thinking with awe of the tremendous powers by which our little lives are encompassed, to consider how beneficent they are and how upon the smallest flower and leaf there was already a freshness poured from all this seeming rage which seemed to make creation new again.

"Is it not dangerous to sit in so exposed a place?"

"Oh, no, Esther dear!" said Ada quietly.

Ada said it to me, but I had not spoken.

The beating of my heart came back again. I had never heard the voice, as I had never seen the face, but it affected me in the same strange way. Again, in a moment, there arose before my mind innumerable pictures of myself.

Lady Dedlock had taken shelter in the lodge before our arrival there and had come out of the gloom within. She stood behind my chair with her hand upon it. I saw her with her hand close to my shoulder when I turned my head.

"I have frightened you?" she said.

No. It was not fright. Why should I be frightened!

"I believe," said Lady Dedlock to my guardian, "I have the pleasure of speaking to Mr. Jarndyce."

"Your remembrance does me more honour than I had supposed it would, Lady Dedlock," he returned.

Kim wrote: "

Caddy's Flowers

Chapter 17

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Why, Caddy, my dear," said I, "what beautiful flowers!"

She had such an exquisite little nosegay in her hand.

"Indeed, I think so, Esther,"..."

Thank you Kim. In this illustration by Phiz we have the ability to see Esther’s face. Now, why would that be?

If we consider that the two other young ladies in the illustration are Ada and Caddy there might be a slight suggestion of foreshadowing in the illustration. Ada and Caddy are either betrothed or in a committed relationship. Esther is not, and yet it is apparent from the dialogue that the flowers are meant for Esther. This could suggest that Esther, the third young lady in the illustration, is beloved as well. But what does the fact that Esther’s face is showing in this illustration have to do with a potential lover? Well, it could be an indication of who the lover is and how he will respond when he sees Esther again.

In the illustration we see a large mirror behind Caddy and Esther. The presence of the mirror reminds us that references to mirrors, glass, and broken glass have all been associated with Esther throughout the novel so far. Here, we see that Esther is not looking into a mirror. She does not see herself. Esther only sees another person in love, a person who is holding flowers that are meant for Esther. Esther sees in Caddy, symbolically, a reflection of Esther’s own future.

Caddy's Flowers

Chapter 17

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Why, Caddy, my dear," said I, "what beautiful flowers!"

She had such an exquisite little nosegay in her hand.

"Indeed, I think so, Esther,"..."

Thank you Kim. In this illustration by Phiz we have the ability to see Esther’s face. Now, why would that be?

If we consider that the two other young ladies in the illustration are Ada and Caddy there might be a slight suggestion of foreshadowing in the illustration. Ada and Caddy are either betrothed or in a committed relationship. Esther is not, and yet it is apparent from the dialogue that the flowers are meant for Esther. This could suggest that Esther, the third young lady in the illustration, is beloved as well. But what does the fact that Esther’s face is showing in this illustration have to do with a potential lover? Well, it could be an indication of who the lover is and how he will respond when he sees Esther again.

In the illustration we see a large mirror behind Caddy and Esther. The presence of the mirror reminds us that references to mirrors, glass, and broken glass have all been associated with Esther throughout the novel so far. Here, we see that Esther is not looking into a mirror. She does not see herself. Esther only sees another person in love, a person who is holding flowers that are meant for Esther. Esther sees in Caddy, symbolically, a reflection of Esther’s own future.

I very much like the Phiz sketch in comment 34 of the three young women, better than the published one that Kim posted first.

I very much like the Phiz sketch in comment 34 of the three young women, better than the published one that Kim posted first. You see so much more in these illustrations than I do, Peter. It's interesting to hear your interpretations.

I wonder what Kyd's wife looked like....

Kim wrote: "Jo in Bleak House. Illustration for Beautiful Stories about Children by Charles Dickens retold by his Granddaughter and others.

Kim wrote: "Jo in Bleak House. Illustration for Beautiful Stories about Children by Charles Dickens retold by his Granddaughter and others. Not sure I would have characterized this--so far at least--as a Beautiful Story about Children?

Mary Lou wrote: "You see so much more in these illustrations than I do, Peter. It's interesting to hear your interpretations."

Mary Lou wrote: "You see so much more in these illustrations than I do, Peter. It's interesting to hear your interpretations."Agreed. Thanks, Peter and Kim.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Jo in Bleak House. Illustration for Beautiful Stories about Children by Charles Dickens retold by his Granddaughter and others.

Not sure I would have characterized this--so far at lea..."

I wouldn't either, especially not the scene he picked.

Not sure I would have characterized this--so far at lea..."

I wouldn't either, especially not the scene he picked.

Mary Lou wrote: "I very much like the Phiz sketch in comment 34 of the three young women, better than the published one that Kim posted first.

You see so much more in these illustrations than I do, Peter. It's in..."

Mary Lou

Let’s hope Kyd never gave his wife a picture of herself ... especially for Valentine’s Day.

You see so much more in these illustrations than I do, Peter. It's in..."

Mary Lou

Let’s hope Kyd never gave his wife a picture of herself ... especially for Valentine’s Day.

Kim wrote: "And Mr. and Mrs. Snagsby:

Mrs. Snagsby looks more like a man than Mr. Snagsby does."

And she does not look very little at all :-)

Mrs. Snagsby looks more like a man than Mr. Snagsby does."

And she does not look very little at all :-)

Peter wrote: "Let’s hope Kyd never gave his wife a picture of herself ... especially for Valentine’s Day."

And if he did, this would probably have been their last Valentine's Day.

And if he did, this would probably have been their last Valentine's Day.

I can't find an image of Kyd's wife anywhere and only one of him that he did himself. Here you go:

Whenever I look for his wife no matter how I enter it in the search engine I get these three illustrations first:

I wonder if he used her for his model. Hopefully not.

I wonder if he used her for his model. Hopefully not.

Well, at least in his self-portrait and in 2 of the 3 characters that came up in your search for his wife, they are smiling. That seems to be a rare feature in his illustrations.

Well, at least in his self-portrait and in 2 of the 3 characters that came up in your search for his wife, they are smiling. That seems to be a rare feature in his illustrations.

I think it is probably good his wife couldn't type "Kyd's wife" or some such wording into the search engine of her computer and see what would come up.

I'm still looking for images of Kyd, his wife, or both of them and haven't found any yet. I did find some unusual illustrations, aren't all Kyd illustrations unusual? - This time they aren't from Dickens books. It is a set of postcards with the name "Heads and the Tales They Tell". Only Kyd can come up with some of this stuff:

The Fearsome Woman

The Fearsome Woman

This week we begin with Chapter 17 which is another one of "Esther's narratives" and that is the title of the chapter, again. Esther begins by telling us that Richard comes to visit them often while they are in London and his visits are always delightful, I'm not sure I would think so, I find him annoying, but then again not nearly as annoying as Mr. Skimpole, so perhaps his visits are delightful. We are told this about Richard:

"They were good qualities, without which no high place can be meritoriously won, but like fire and water, though excellent servants, they were very bad masters. If they had been under Richard's direction, they would have been his friends; but Richard being under their direction, they became his enemies."

I'm a little confused as to what these good qualities are that no high place can be won without them. Is it his" good spirits, his good temper, his gaiety and freshness" she mentions? because she also says he had no habits of concentration and application, which would seem as important to me for a high place as being cheerful. Anyway, whatever it is he doesn't seem to be winning that higher place, for when Mr. and Mrs. Badger come for a visit, after they get past the droning on about the past husbands of Mrs. Badger they do finally tell them that Richard "has not chosen his profession advisedly". Mrs. Badger tells them that Richard has no interest in the profession and finds it a tiresome pursuit. When Mr. Badger is asked whether he agrees with his wife he says: