The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Bleak House

Bleak House

>

Bleak House, Chp. 26-29

Chapter 27, More Old Soldiers Than One, smoothly takes up the action of the preceding one. Mr. George is taken to no one else but Mr. Tulkinghorn, and while they are waiting for the lawyer to appear, he comes to look at a box of files bearing Sir Leicester’s name. This and the reference to Chesney Wold sends him off into a brown study. However, Mr. Smallweed soon brings him back into reality by expounding on how rich Mr. Tulkinghorn is supposed to be.

On arriving, Mr. Tulkinghorn explains to Mr. George that he is very interested in comparing the handwriting of Captain Hawdon with the handwriting of another document he has got. We all know what document he is thinking of, I suppose. However, he is not willing to let Mr. George in on his motives for doing so, and that’s why Mr. George, to Mr. Smallweed’s great annoyance – it’s quite in tune with Mr. Smallweed’s character to grovel before someone like Mr. Tulkinghorn –, demands that he be given time to think matters over.

He now visits the Bagnet family, a new set of characters, in order to hear Mr. Bagnet’s opinion on the matter. As a very clever and trustworthy man, Mr. Bagnet can dispense with coating his opinion in his own words but he leaves it to his wife to say what he thinks about the whole matter. And what he thinks is that Mr. George should not get meddled up with business he does not fully understand, and this is precisely what Mr. George had already made up his mind to.

A few remarks aside on the Bagnets while Mr. George is still enjoying his satisfaction as to Mr. Bagnet’s advice confirming his own feelings: Mr. George wanting their advice seems a rather threadbare excuse for introducing them into the novel, and so the question remains what purpose they fulfill. Apparently, Mrs. Bagnet is very worried that Mr. George might, once again, persuade her husband to leave behind wife and children and to go abroad, and when she asks Mr. George about why it is that h never settled down in life, he says that it must be the animal in him. We also learn that he had the chance of marrying a widow and of having a happy family like the one we find described in the Bagnets, a chance he, however, forewent.

So are the Bagnets in the novel only to give Mr. George more background, like Phil Squod? If so, Mr. George must be quite an important character for the novel. Be that as it may, some Curiosity aptly pointed out that so far, Bleak House has not given us any really happy family, with the possible exception of the jerry-rigged Jarndyce household (and even there is a slight rift coming to the surface), but now we have the Bagnets, who seem to be the first truly happy family in our novel.

Later in the evening, Mr. George returns to Mr. Tulkinghorn’s rooms in order to tell him that he decided against the proposed bargain. While, at his first signs of reluctance, Mr. Smallweed has flown into a rage, Mr. Tulkinghorn has maintained a surface of indifference and coolness. Now, however, he is quite put out at received Mr. George’s final decision, and the chapter ends thus:

”’Have you changed your mind? Or are you in the same mind?’ Mr. Tulkinghorn demands. But he knows well enough at a glance.

‘In the same mind, sir.’

‘I thought so. That's sufficient. You can go. So you are the man,’ says Mr. Tulkinghorn, opening his door with the key, ‘in whose hiding-place Mr. Gridley was found?’

‘Yes, I AM the man,’ says the trooper, stopping two or three stairs down. ‘What then, sir?’

‘What then? I don't like your associates. You should not have seen the inside of my door this morning if I had thought of your being that man. Gridley? A threatening, murderous, dangerous fellow.’

With these words, spoken in an unusually high tone for him, the lawyer goes into his rooms and shuts the door with a thundering noise.

Mr. George takes his dismissal in great dudgeon, the greater because a clerk coming up the stairs has heard the last words of all and evidently applies them to him. ‘A pretty character to bear,’ the trooper growls with a hasty oath as he strides downstairs. ‘A threatening, murderous, dangerous fellow!’ And looking up, he sees the clerk looking down at him and marking him as he passes a lamp. This so intensifies his dudgeon that for five minutes he is in an ill humour. But he whistles that off like the rest of it and marches home to the shooting gallery.”

I have quoted this because it might be of importance with regard to later events …

On arriving, Mr. Tulkinghorn explains to Mr. George that he is very interested in comparing the handwriting of Captain Hawdon with the handwriting of another document he has got. We all know what document he is thinking of, I suppose. However, he is not willing to let Mr. George in on his motives for doing so, and that’s why Mr. George, to Mr. Smallweed’s great annoyance – it’s quite in tune with Mr. Smallweed’s character to grovel before someone like Mr. Tulkinghorn –, demands that he be given time to think matters over.

He now visits the Bagnet family, a new set of characters, in order to hear Mr. Bagnet’s opinion on the matter. As a very clever and trustworthy man, Mr. Bagnet can dispense with coating his opinion in his own words but he leaves it to his wife to say what he thinks about the whole matter. And what he thinks is that Mr. George should not get meddled up with business he does not fully understand, and this is precisely what Mr. George had already made up his mind to.

A few remarks aside on the Bagnets while Mr. George is still enjoying his satisfaction as to Mr. Bagnet’s advice confirming his own feelings: Mr. George wanting their advice seems a rather threadbare excuse for introducing them into the novel, and so the question remains what purpose they fulfill. Apparently, Mrs. Bagnet is very worried that Mr. George might, once again, persuade her husband to leave behind wife and children and to go abroad, and when she asks Mr. George about why it is that h never settled down in life, he says that it must be the animal in him. We also learn that he had the chance of marrying a widow and of having a happy family like the one we find described in the Bagnets, a chance he, however, forewent.

So are the Bagnets in the novel only to give Mr. George more background, like Phil Squod? If so, Mr. George must be quite an important character for the novel. Be that as it may, some Curiosity aptly pointed out that so far, Bleak House has not given us any really happy family, with the possible exception of the jerry-rigged Jarndyce household (and even there is a slight rift coming to the surface), but now we have the Bagnets, who seem to be the first truly happy family in our novel.

Later in the evening, Mr. George returns to Mr. Tulkinghorn’s rooms in order to tell him that he decided against the proposed bargain. While, at his first signs of reluctance, Mr. Smallweed has flown into a rage, Mr. Tulkinghorn has maintained a surface of indifference and coolness. Now, however, he is quite put out at received Mr. George’s final decision, and the chapter ends thus:

”’Have you changed your mind? Or are you in the same mind?’ Mr. Tulkinghorn demands. But he knows well enough at a glance.

‘In the same mind, sir.’

‘I thought so. That's sufficient. You can go. So you are the man,’ says Mr. Tulkinghorn, opening his door with the key, ‘in whose hiding-place Mr. Gridley was found?’

‘Yes, I AM the man,’ says the trooper, stopping two or three stairs down. ‘What then, sir?’

‘What then? I don't like your associates. You should not have seen the inside of my door this morning if I had thought of your being that man. Gridley? A threatening, murderous, dangerous fellow.’

With these words, spoken in an unusually high tone for him, the lawyer goes into his rooms and shuts the door with a thundering noise.

Mr. George takes his dismissal in great dudgeon, the greater because a clerk coming up the stairs has heard the last words of all and evidently applies them to him. ‘A pretty character to bear,’ the trooper growls with a hasty oath as he strides downstairs. ‘A threatening, murderous, dangerous fellow!’ And looking up, he sees the clerk looking down at him and marking him as he passes a lamp. This so intensifies his dudgeon that for five minutes he is in an ill humour. But he whistles that off like the rest of it and marches home to the shooting gallery.”

I have quoted this because it might be of importance with regard to later events …

In Chapter 28, The Ironmaster, the scene changes for Chesney Wold once more, and we are presented with yet another character – the man for whom the chapter was named, i.e. Mrs. Rouncewell’s younger son, the industrialist.

This is really a chapter about class consciousness and the social changes that England saw in the 19th century. At its beginning we find the following amusing observation:

It is a melancholy truth that even great men have their poor relations. Indeed great men have often more than their fair share of poor relations, inasmuch as very red blood of the superior quality, like inferior blood unlawfully shed, WILL cry aloud and WILL be heard. Sir Leicester's cousins, in the remotest degree, are so many murders in the respect that they ‘will out.’ Among whom there are cousins who are so poor that one might almost dare to think it would have been the happier for them never to have been plated links upon the Dedlock chain of gold, but to have been made of common iron at first and done base service.

Service, however (with a few limited reservations, genteel but not profitable), they may not do, being of the Dedlock dignity. So they visit their richer cousins, and get into debt when they can, and live but shabbily when they can't, and find—the women no husbands, and the men no wives—and ride in borrowed carriages, and sit at feasts that are never of their own making, and so go through high life. The rich family sum has been divided by so many figures, and they are the something over that nobody knows what to do with.”

Apparently the social codex made it impossible for the poorer relations of a member of the gentry like Sir Leicester to roll up their sleeves and to find an occupation enabling them to live by their own means. Instead they rely on money sent to them from their richer relations. It must have been a rather depressing kind of existence, and Dickens rolls all those nameless cousins into one by creating the minor minor character of Volumnia, whose name alone is a bitter joke, and who is described like this:

”Of these, foremost in the front rank stands Volumnia Dedlock, a young lady (of sixty) who is doubly highly related, having the honour to be a poor relation, by the mother's side, to another great family. Miss Volumnia, displaying in early life a pretty talent for cutting ornaments out of coloured paper, and also for singing to the guitar in the Spanish tongue, and propounding French conundrums in country houses, passed the twenty years of her existence between twenty and forty in a sufficiently agreeable manner. Lapsing then out of date and being considered to bore mankind by her vocal performances in the Spanish language, she retired to Bath, where she lives slenderly on an annual present from Sir Leicester and whence she makes occasional resurrections in the country houses of her cousins. She has an extensive acquaintance at Bath among appalling old gentlemen with thin legs and nankeen trousers, and is of high standing in that dreary city. But she is a little dreaded elsewhere in consequence of an indiscreet profusion in the article of rouge and persistency in an obsolete pearl necklace like a rosary of little bird's-eggs.”

Amidst all those cousins, whose presence seems to make Lady Dedlock even drearier but who are borne by Sir Leicester as he would bear any other duty attached to his station in life, the master and the mistress of Chesney Wold pass their evenings when the Ironmaster – who, to Sir Leicester’s dismay was even offered a seat in Parliament – asks for an interview. Sir Leicester notices the mixture of respect and self-confidence with which Mr. Rouncewell deals with him – to him, another sign of the opening of floodgates and all that. Mr. Rouncewell informs Sir Leicester that his son has fallen in love with the maidservant Rosa and that Mr. Rouncewell would be willing to accept an engagement on condition that Rosa leave Chesney Wold and be put into a school in order to enhance her knowledge and refine her manners and thus become a more eligible woman for his son. Sir Leicester is indignant at the implication that Rosa’s station at Chesney Wold would not already make her a fit spouse for the son of an – excuse the blunt term – ironmaster. The two men do not come to an agreement, and it seems as though Mr. Rouncewell is going to make his son bury his hopes as to Rosa. So are we going to get another tragic lovestory? It is quite interesting that Lady Dedlock seems to be more willing to listen to Mr. Rouncewell and to comply with his wishes.

Mr. Rouncewell and Sir Leicester’s quarrel is illustrative of the clash between two concepts of how society should be organized. Whereas Sir Leicester, a representative of the gentry, believes in privilege and in the idea that everyone is allotted their social position by birth, Mr. Rouncewell, the self-made man, seems to think that a person can rise by hard and diligent work and by education. Nevertheless, he is adamant about certain requirements that his future daughter-in-law must fulfill, probably because he expects his children to advance in life and not to marry down – “marrying down” meaning, for him, to choose a spouse of moral or intellectual inferiority.

Lady Dedlock’s more understanding attitude is mingled with a sense of depression – as Jantine rightly mentioned in an earlier thread –, which becomes clear when she tells Rosa:

”’Confide in me, my child. Don't fear me. I wish you to be happy, and will make you so—if I can make anybody happy on this earth.’”

This is really a chapter about class consciousness and the social changes that England saw in the 19th century. At its beginning we find the following amusing observation:

It is a melancholy truth that even great men have their poor relations. Indeed great men have often more than their fair share of poor relations, inasmuch as very red blood of the superior quality, like inferior blood unlawfully shed, WILL cry aloud and WILL be heard. Sir Leicester's cousins, in the remotest degree, are so many murders in the respect that they ‘will out.’ Among whom there are cousins who are so poor that one might almost dare to think it would have been the happier for them never to have been plated links upon the Dedlock chain of gold, but to have been made of common iron at first and done base service.

Service, however (with a few limited reservations, genteel but not profitable), they may not do, being of the Dedlock dignity. So they visit their richer cousins, and get into debt when they can, and live but shabbily when they can't, and find—the women no husbands, and the men no wives—and ride in borrowed carriages, and sit at feasts that are never of their own making, and so go through high life. The rich family sum has been divided by so many figures, and they are the something over that nobody knows what to do with.”

Apparently the social codex made it impossible for the poorer relations of a member of the gentry like Sir Leicester to roll up their sleeves and to find an occupation enabling them to live by their own means. Instead they rely on money sent to them from their richer relations. It must have been a rather depressing kind of existence, and Dickens rolls all those nameless cousins into one by creating the minor minor character of Volumnia, whose name alone is a bitter joke, and who is described like this:

”Of these, foremost in the front rank stands Volumnia Dedlock, a young lady (of sixty) who is doubly highly related, having the honour to be a poor relation, by the mother's side, to another great family. Miss Volumnia, displaying in early life a pretty talent for cutting ornaments out of coloured paper, and also for singing to the guitar in the Spanish tongue, and propounding French conundrums in country houses, passed the twenty years of her existence between twenty and forty in a sufficiently agreeable manner. Lapsing then out of date and being considered to bore mankind by her vocal performances in the Spanish language, she retired to Bath, where she lives slenderly on an annual present from Sir Leicester and whence she makes occasional resurrections in the country houses of her cousins. She has an extensive acquaintance at Bath among appalling old gentlemen with thin legs and nankeen trousers, and is of high standing in that dreary city. But she is a little dreaded elsewhere in consequence of an indiscreet profusion in the article of rouge and persistency in an obsolete pearl necklace like a rosary of little bird's-eggs.”

Amidst all those cousins, whose presence seems to make Lady Dedlock even drearier but who are borne by Sir Leicester as he would bear any other duty attached to his station in life, the master and the mistress of Chesney Wold pass their evenings when the Ironmaster – who, to Sir Leicester’s dismay was even offered a seat in Parliament – asks for an interview. Sir Leicester notices the mixture of respect and self-confidence with which Mr. Rouncewell deals with him – to him, another sign of the opening of floodgates and all that. Mr. Rouncewell informs Sir Leicester that his son has fallen in love with the maidservant Rosa and that Mr. Rouncewell would be willing to accept an engagement on condition that Rosa leave Chesney Wold and be put into a school in order to enhance her knowledge and refine her manners and thus become a more eligible woman for his son. Sir Leicester is indignant at the implication that Rosa’s station at Chesney Wold would not already make her a fit spouse for the son of an – excuse the blunt term – ironmaster. The two men do not come to an agreement, and it seems as though Mr. Rouncewell is going to make his son bury his hopes as to Rosa. So are we going to get another tragic lovestory? It is quite interesting that Lady Dedlock seems to be more willing to listen to Mr. Rouncewell and to comply with his wishes.

Mr. Rouncewell and Sir Leicester’s quarrel is illustrative of the clash between two concepts of how society should be organized. Whereas Sir Leicester, a representative of the gentry, believes in privilege and in the idea that everyone is allotted their social position by birth, Mr. Rouncewell, the self-made man, seems to think that a person can rise by hard and diligent work and by education. Nevertheless, he is adamant about certain requirements that his future daughter-in-law must fulfill, probably because he expects his children to advance in life and not to marry down – “marrying down” meaning, for him, to choose a spouse of moral or intellectual inferiority.

Lady Dedlock’s more understanding attitude is mingled with a sense of depression – as Jantine rightly mentioned in an earlier thread –, which becomes clear when she tells Rosa:

”’Confide in me, my child. Don't fear me. I wish you to be happy, and will make you so—if I can make anybody happy on this earth.’”

Chapter 29 finally brings the different strands of the plot together and thereby confirms many hypotheses we might have formed up to now. Being happily relieved of their cumbersome cousins for the time being, the Dedlocks are back in their London house, where their regular visit is Mr. Tulkinghorn – on business, of course. Yet he introduces an element of menace into Lady Dedlock’s life:

”Mr. Tulkinghorn comes and goes pretty often, there being estate business to do, leases to be renewed, and so on. He sees my Lady pretty often, too; and he and she are as composed, and as indifferent, and take as little heed of one another, as ever. Yet it may be that my Lady fears this Mr. Tulkinghorn and that he knows it. It may be that he pursues her doggedly and steadily, with no touch of compunction, remorse, or pity. It may be that her beauty and all the state and brilliancy surrounding her only gives him the greater zest for what he is set upon and makes him the more inflexible in it. Whether he be cold and cruel, whether immovable in what he has made his duty, whether absorbed in love of power, whether determined to have nothing hidden from him in ground where he has burrowed among secrets all his life, whether he in his heart despises the splendour of which he is a distant beam, whether he is always treasuring up slights and offences in the affability of his gorgeous clients—whether he be any of this, or all of this, it may be that my Lady had better have five thousand pairs of fashionable eyes upon her, in distrustful vigilance, than the two eyes of this rusty lawyer with his wisp of neckcloth and his dull black breeches tied with ribbons at the knees.”

Here the narrator also muses on the motives Mr. Tulkinghorn might have for pursuing Lady Dedlock with his private investigations, and he leaves it for the reader to decide whether Mr. Tulkinghorn acts out of envy, hatred or simple lust for power. In short, even to the omniscient narrator the family lawyer remains an unfathomable source of mystery. This might be ironic but it also enhances the fascination of the altogether rather intangible and vague Mr. Tulkinghorn: Can it really be the case that his knowledge of what all those noble families he serves have in their closets, skeletons and fleshier parts, has filled him with scorn for them? Has he grown a cynic by earning his bread (or cake) helping them uphold their unblemished reputations regardless of all their private affairs?

One afternoon, the servant introduces The young man by the name of Guppy, causing Sir Leicester to wonder at his wife’s seeming familiarity with such an individual. Being the gentleman he is, however, he retires, and leaves a lacklustre Mr. Guppy in the presence of Lady Dedlock. We get to know that Mr. Guppy has repeatedly pestered Lady Dedlock with letters in order to get that interview, and whereas at first Lady Dedlock treats him with scathing indifference and haughtiness, she finally even asks him to sit down when it becomes clear to her that Mr. Guppy has unraveled quite a lot of details her former life and that he knows Mr. Tulkinghorn. Mr. Guppy points out the likeness between Esther Summerson and Lady Dedlock, and he also says that he knows that Esther was brought up by Mrs. Barbary and that Esther’s real name is not Summerson but Hawdon. He also cunningly implies that he knows that the lady that wanted to see Hawdon’s grave is Lady Dedlock herself. Furhtermore he says that he is going to obtain some letters written by Captain Hawdon and that he would be willing to open those letters and go through them in Lady Dedlock’s presence if she is interested in them. After some hesitation Lady Dedlock professes her interest, and Mr. Guppy, who does not want any money at all but implies that he is doing all this for the benefit of Esther, who might thereby become a party in Jarndyce and Jarndyce – what a benefit indeed! –, takes his leave.

Left alone, Lady Dedlock bursts into tears and cries:

”’O my child, my child! Not dead in the first hours of her life, as my cruel sister told me, but sternly nurtured by her, after she had renounced me and my name! O my child, O my child!‘“

So we know that Lady Dedlock was not cruel enough to renounce her child but was a victim of her sister’s heartlessness. That question being cleared up, however, another one arises – namely the one about Mr. Guppy’s motives. How did you read his offer of not reading the papers before he had taken them to Lady Dedlock, and his insistence that all this should happen at Lady Dedlock’s behest? And his hint that their meeting’s being made known would cause him trouble, could this not also be read as an indirect hint as to something else?

”Mr. Tulkinghorn comes and goes pretty often, there being estate business to do, leases to be renewed, and so on. He sees my Lady pretty often, too; and he and she are as composed, and as indifferent, and take as little heed of one another, as ever. Yet it may be that my Lady fears this Mr. Tulkinghorn and that he knows it. It may be that he pursues her doggedly and steadily, with no touch of compunction, remorse, or pity. It may be that her beauty and all the state and brilliancy surrounding her only gives him the greater zest for what he is set upon and makes him the more inflexible in it. Whether he be cold and cruel, whether immovable in what he has made his duty, whether absorbed in love of power, whether determined to have nothing hidden from him in ground where he has burrowed among secrets all his life, whether he in his heart despises the splendour of which he is a distant beam, whether he is always treasuring up slights and offences in the affability of his gorgeous clients—whether he be any of this, or all of this, it may be that my Lady had better have five thousand pairs of fashionable eyes upon her, in distrustful vigilance, than the two eyes of this rusty lawyer with his wisp of neckcloth and his dull black breeches tied with ribbons at the knees.”

Here the narrator also muses on the motives Mr. Tulkinghorn might have for pursuing Lady Dedlock with his private investigations, and he leaves it for the reader to decide whether Mr. Tulkinghorn acts out of envy, hatred or simple lust for power. In short, even to the omniscient narrator the family lawyer remains an unfathomable source of mystery. This might be ironic but it also enhances the fascination of the altogether rather intangible and vague Mr. Tulkinghorn: Can it really be the case that his knowledge of what all those noble families he serves have in their closets, skeletons and fleshier parts, has filled him with scorn for them? Has he grown a cynic by earning his bread (or cake) helping them uphold their unblemished reputations regardless of all their private affairs?

One afternoon, the servant introduces The young man by the name of Guppy, causing Sir Leicester to wonder at his wife’s seeming familiarity with such an individual. Being the gentleman he is, however, he retires, and leaves a lacklustre Mr. Guppy in the presence of Lady Dedlock. We get to know that Mr. Guppy has repeatedly pestered Lady Dedlock with letters in order to get that interview, and whereas at first Lady Dedlock treats him with scathing indifference and haughtiness, she finally even asks him to sit down when it becomes clear to her that Mr. Guppy has unraveled quite a lot of details her former life and that he knows Mr. Tulkinghorn. Mr. Guppy points out the likeness between Esther Summerson and Lady Dedlock, and he also says that he knows that Esther was brought up by Mrs. Barbary and that Esther’s real name is not Summerson but Hawdon. He also cunningly implies that he knows that the lady that wanted to see Hawdon’s grave is Lady Dedlock herself. Furhtermore he says that he is going to obtain some letters written by Captain Hawdon and that he would be willing to open those letters and go through them in Lady Dedlock’s presence if she is interested in them. After some hesitation Lady Dedlock professes her interest, and Mr. Guppy, who does not want any money at all but implies that he is doing all this for the benefit of Esther, who might thereby become a party in Jarndyce and Jarndyce – what a benefit indeed! –, takes his leave.

Left alone, Lady Dedlock bursts into tears and cries:

”’O my child, my child! Not dead in the first hours of her life, as my cruel sister told me, but sternly nurtured by her, after she had renounced me and my name! O my child, O my child!‘“

So we know that Lady Dedlock was not cruel enough to renounce her child but was a victim of her sister’s heartlessness. That question being cleared up, however, another one arises – namely the one about Mr. Guppy’s motives. How did you read his offer of not reading the papers before he had taken them to Lady Dedlock, and his insistence that all this should happen at Lady Dedlock’s behest? And his hint that their meeting’s being made known would cause him trouble, could this not also be read as an indirect hint as to something else?

You've done a splendid job at summarizing these chapters without the benefit of notes, Tristram. I made very few notes, myself, this week, but I did wonder about one thing as I read about Mr. Smallweed's visit to the shooting gallery. Does Smallweed actually have a "friend in the city"? Is the friend reminiscent of Mrs. 'arris, Sarah Gamp's unseen friend in Chuzzlewit? Or is he really the Jorkins to Smallweed's Spenlow, someone on whom Smallwood can place the onus of unpopular fiscal decisions? Will we ever know?

You've done a splendid job at summarizing these chapters without the benefit of notes, Tristram. I made very few notes, myself, this week, but I did wonder about one thing as I read about Mr. Smallweed's visit to the shooting gallery. Does Smallweed actually have a "friend in the city"? Is the friend reminiscent of Mrs. 'arris, Sarah Gamp's unseen friend in Chuzzlewit? Or is he really the Jorkins to Smallweed's Spenlow, someone on whom Smallwood can place the onus of unpopular fiscal decisions? Will we ever know? As many times as I've read this book, I'd forgotten some of my favorite characters and was delighted to make the acquaintance of the Bagnets again. Their little deception about Mrs. Bagnet summing up Mr. Bagnet's thoughts is another one of the charming quirks Dickens bestows on his characters that makes them memorable. (And, yes... I see the irony of calling them memorable after admitting to forgetting them, but you know what I mean). I look forward to spending more time in their cozy home.

Every now and then our narrator mentions that Mr. George smiles. When we're told this, I feel as if it must be a rare and notable thing. I imagine it to be a genuine smile that completely changes his countenance, and is a great gift to those who have the opportunity to glimpse it. It's as if he believes he's somehow not entitled to smile, and that when he catches himself at it, he quickly goes back to his serious demeanor. I hope the dark cloud of his past will be lifted at some point, and that he'll finally be able to share that glorious smile freely and without guilt.

Say what you want about Guppy... he knows how to put two and two together to come up with four. What's his goal? Will showing his hand to Lady Dedlock prove to be advantageous or disastrous for each of them? How will my Lady explain Guppy's visit to Sir Leicester?

Tristram wrote: "In Chapter 28, The Ironmaster, the scene changes for Chesney Wold once more, and we are presented with yet another character – the man for whom the chapter was named, i.e. Mrs. Rouncewell’s younger..."

Tristram

Chapter 28 is indeed a great chapter where we get to enjoy Dickens paint the two worlds of Victorian England. On the one hand we get the world of Sir Leicester and his home. Chesney Wold is set in the past. With phrases such as “ancient house, rooted in that quiet park, where the ivy and the moss have had time to mature” and “where the sundial on the terrace has dumbly recorded for centuries that Time, which was ... the property of every Dedlock” we are in the past. With Mrs Rouncewell’s son, on the other hand, we see a man who has risen from a “workman’s wages” to be a captain of industry and who believes his children “worthy of any station.”

Poor Sir Leicester. He almost chokes when confronted with the idea that Rouncewell is drawing a parallel between Chesney Wold and a factory. In part, the debate between the men centres around the concept of education. Sir Leicester’s sundial records that time has not changed in centuries. He is wrong. Progress in the form of coal and smoke and the creation of iron has come to England. I don’t think it is a coincidence that Rouncewell is an Ironmaster. He is the future.

This will not be the first time we we see these two contrary worlds compared.

Tristram

Chapter 28 is indeed a great chapter where we get to enjoy Dickens paint the two worlds of Victorian England. On the one hand we get the world of Sir Leicester and his home. Chesney Wold is set in the past. With phrases such as “ancient house, rooted in that quiet park, where the ivy and the moss have had time to mature” and “where the sundial on the terrace has dumbly recorded for centuries that Time, which was ... the property of every Dedlock” we are in the past. With Mrs Rouncewell’s son, on the other hand, we see a man who has risen from a “workman’s wages” to be a captain of industry and who believes his children “worthy of any station.”

Poor Sir Leicester. He almost chokes when confronted with the idea that Rouncewell is drawing a parallel between Chesney Wold and a factory. In part, the debate between the men centres around the concept of education. Sir Leicester’s sundial records that time has not changed in centuries. He is wrong. Progress in the form of coal and smoke and the creation of iron has come to England. I don’t think it is a coincidence that Rouncewell is an Ironmaster. He is the future.

This will not be the first time we we see these two contrary worlds compared.

The juxtaposition between the old world of Chesney Wold and the new world represented by the Ironmaster is indeed striking. There are signs indicating that the old world is not as strong and long-lasting as it seems, e.g. the frequent mentions of the Ghost Walk. At the beginning of Chapter 29, I found this:

The slowly, but inevitably falling leaf may be read as a symbol of the limited number of days of every person's life, but also of the caducity of everything that seems made for eternity - Ozymandias and all that -, but in the context of the last few chapters, I think it could also be read as impending doom hanging over Sir Leicester and his private world: The leaves fall slowly, but they fall - just as Mr Guppy might proceed slowly in his investigations but still we see he has already gathered a lot of information.

Then there is that brilliant sentence from Chapter 28:

You may take it as a general truth, but you may also remember that the wives of great men have their poor relations and that their blood might also cry.

"Around and around the house the leaves fall thick, but never fast, for they come circling down with a dead lightness that is sombre and slow."

The slowly, but inevitably falling leaf may be read as a symbol of the limited number of days of every person's life, but also of the caducity of everything that seems made for eternity - Ozymandias and all that -, but in the context of the last few chapters, I think it could also be read as impending doom hanging over Sir Leicester and his private world: The leaves fall slowly, but they fall - just as Mr Guppy might proceed slowly in his investigations but still we see he has already gathered a lot of information.

Then there is that brilliant sentence from Chapter 28:

"It is a melancholy truth that even great men have their poor relations. Indeed great men have often more than their fair share of poor relations, inasmuch as very red blood of the superior quality, like inferior blood unlawfully shed, will cry aloud and will be heard."

You may take it as a general truth, but you may also remember that the wives of great men have their poor relations and that their blood might also cry.

Mary Lou wrote: "Does Smallweed actually have a "friend in the city"? Is the friend reminiscent of Mrs. 'arris, Sarah Gamp's unseen friend in Chuzzlewit? Or is he really the Jorkins to Smallweed's Spenlow, someone on whom Smallwood can place the onus of unpopular fiscal decisions? Will we ever know?"

I think that Grandfather Smallweed does not really have a friend in the City, but that it is just a ruse to put pressure on Mr. George without committing himself. I sometimes use this technique when preparing my students for exams. I usually say, "Why, what you have said there is a very good starting point and there is a lot to say in favour for it, and I would be quite satisfied with such an answer but I am not tooooo sure that the other members of the examination board will be so satisfied. Therefore, let's dig a little deeper." This way, I can prepare my students better without seeming to become myself their opponent.

I think that Grandfather Smallweed does not really have a friend in the City, but that it is just a ruse to put pressure on Mr. George without committing himself. I sometimes use this technique when preparing my students for exams. I usually say, "Why, what you have said there is a very good starting point and there is a lot to say in favour for it, and I would be quite satisfied with such an answer but I am not tooooo sure that the other members of the examination board will be so satisfied. Therefore, let's dig a little deeper." This way, I can prepare my students better without seeming to become myself their opponent.

I am bouncing back and forth on Mr. Smallweed's friend:

- Mr. Smallweed doesn't have a friend, period, he is too mean to have any friend.

- Mr. Smallweed clearly uses his 'friend in the city' for leverage, and I do think he tells what his friend in the city thinks or does, like Mrs. Gamp used Mrs. Harris, or at best like Mrs. Bagnet obviously tells what she thinks, but like it's Mr. Bagnet's opinion because people give his opinion more weight usually.

- I do think his 'friend in the city' exists, and I think that 'friend in the city' is Tulkinhorn. The guy seems to be some kind of Scrooge: he must earn shitloads of money being an outstanding solicitor of all the mighty and wealthy families, but he still has only one clerk and lives in the rooms where he has his office, and he always wears the same stinky old clothes. He must be filthy rich, and what do (did) the filthy rich do with their money, especially when they know the laws on money as the back of their hand? I think Smallweed is nothing but a go-between so Tulkinhorn does not have to dirty his hands by appearing to be a money lender. It probably pays well enough, but a small money lender like Smallweed wouldn't be able to take those huge risks like lending money to Richard Carstone - with enormous interest, but as George pointed out, with enormous risks of never getting the money back too. Also, isn't it kind of implied by Smallweed that they're going to visit his 'friend in the city', and then they're going to Tulkinhorn?

So yes, while as far as I know it is never spelled out in the novel, and I do think Smallweed blames his 'friend in the city' for things he does not immediately have anything to do with (George being a relatively safe debtor, I am convinced the money he loaned came from Smallweed himself), I also believe the friend in the city does exist and is Tulkinhorn. It would give the guy a whole new layer of nastiness too, and I wouldn't put it past him to be secretly as rich as any of his cliënts.

- Mr. Smallweed doesn't have a friend, period, he is too mean to have any friend.

- Mr. Smallweed clearly uses his 'friend in the city' for leverage, and I do think he tells what his friend in the city thinks or does, like Mrs. Gamp used Mrs. Harris, or at best like Mrs. Bagnet obviously tells what she thinks, but like it's Mr. Bagnet's opinion because people give his opinion more weight usually.

- I do think his 'friend in the city' exists, and I think that 'friend in the city' is Tulkinhorn. The guy seems to be some kind of Scrooge: he must earn shitloads of money being an outstanding solicitor of all the mighty and wealthy families, but he still has only one clerk and lives in the rooms where he has his office, and he always wears the same stinky old clothes. He must be filthy rich, and what do (did) the filthy rich do with their money, especially when they know the laws on money as the back of their hand? I think Smallweed is nothing but a go-between so Tulkinhorn does not have to dirty his hands by appearing to be a money lender. It probably pays well enough, but a small money lender like Smallweed wouldn't be able to take those huge risks like lending money to Richard Carstone - with enormous interest, but as George pointed out, with enormous risks of never getting the money back too. Also, isn't it kind of implied by Smallweed that they're going to visit his 'friend in the city', and then they're going to Tulkinhorn?

So yes, while as far as I know it is never spelled out in the novel, and I do think Smallweed blames his 'friend in the city' for things he does not immediately have anything to do with (George being a relatively safe debtor, I am convinced the money he loaned came from Smallweed himself), I also believe the friend in the city does exist and is Tulkinhorn. It would give the guy a whole new layer of nastiness too, and I wouldn't put it past him to be secretly as rich as any of his cliënts.

Jantine, that is a very interesting and alluring theory, but I think that Grandfather Smallweed only made Mr. Tulkinghorn's acquaintance when the lawyer contacted him in re Captain Hawdon. At least, that is what I gather from the novel. At the same time, I have the impression that Smallweed has been using the device of his friend in the city for a much longer time. As yet, I also have had no hint as to Mr. Tulkinghorn 's doing financial business of any kind: He must earn a lot of money, but I think that it is not so much the money he is after but more the feeling of power he can derive from his knowledge of the secrets of the rich and influential clients he has.

Still, let's keep our eyes open!

Still, let's keep our eyes open!

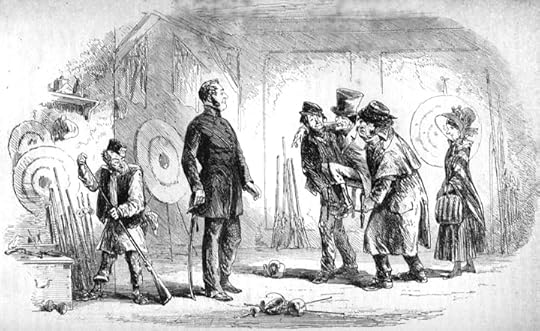

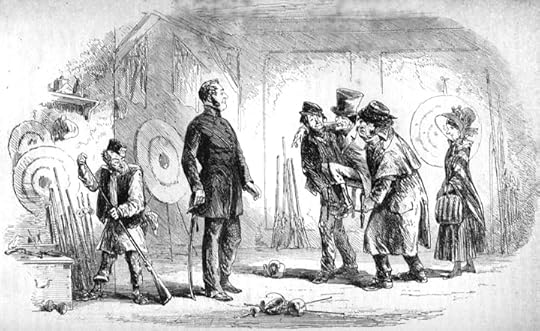

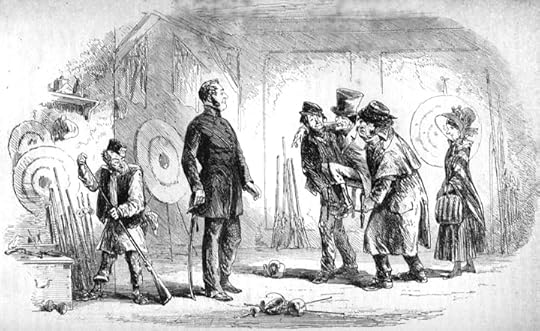

Visitors to the shooting gallery

Chapter 26

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Master and man are . . . disturbed by footsteps in the passage, where they make an unusual sound, denoting the arrival of unusual company. These steps, advancing nearer and nearer to the gallery, bring into it a group at first sight scarcely reconcilable with any day in the year but the fifth of November.

It consists of a limp and ugly figure carried in a chair by two bearers and attended by a lean female with a face like a pinched mask, who might be expected immediately to recite the popular verses commemorative of the time when they did contrive to blow Old England up alive but for her keeping her lips tightly and defiantly closed as the chair is put down. At which point the figure in it gasping, "O Lord! Oh, dear me! I am shaken!" adds, "How de do, my dear friend, how de do?" Mr. George then descries, in the procession, the venerable Mr. Smallweed out for an airing, attended by his granddaughter Judy as body-guard.

"Mr. George, my dear friend," says Grandfather Smallweed, removing his right arm from the neck of one of his bearers, whom he has nearly throttled coming along, "how de do? You're surprised to see me, my dear friend."

"I should hardly have been more surprised to have seen your friend in the city," returns Mr. George.

"I am very seldom out," pants Mr. Smallweed. "I haven't been out for many months. It's inconvenient — and it comes expensive. But I longed so much to see you, my dear Mr. George. How de do, sir?" . . .

"So we got a hackney-cab, and put a chair in it, and just round the corner they lifted me out of the cab and into the chair, and carried me here that I might see my dear friend in his own establishment! This," says Grandfather Smallweed, alluding to the bearer, who has been in danger of strangulation and who withdraws adjusting his windpipe, "is the driver of the cab. He has nothing extra. It is by agreement included in his fare. This person," the other bearer, "we engaged in the street outside for a pint of beer. Which is twopence. Judy, give the person twopence. I was not sure you had a workman of your own here, my dear friend, or we needn't have employed this person."

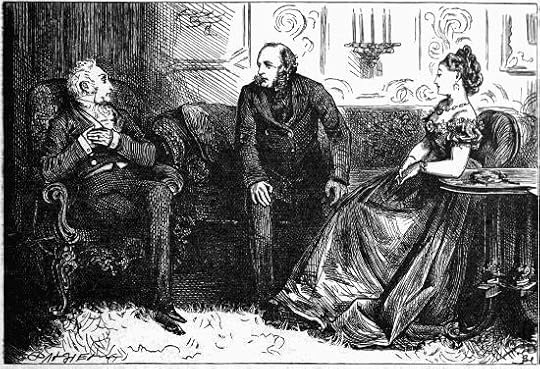

The young man by the name of Guppy

Chapter 29

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Sir Leicester is reading with infinite gravity and state when the door opens, and the Mercury in powder makes this strange announcement, "The young man, my Lady, of the name of Guppy."

Sir Leicester pauses, stares, repeats in a killing voice, "The young man of the name of Guppy?"

Looking round, he beholds The Young Man of the Name of Guppy, much discomfited and not presenting a very impressive letter of introduction in his manner and appearance.

"Pray," says Sir Leicester to Mercury, "what do you mean by announcing with this abruptness a young man of the name of Guppy?"

"I beg your pardon, Sir Leicester, but my Lady said she would see the young man whenever he called. I was not aware that you were here, Sir Leicester."

With this apology, Mercury directs a scornful and indignant look at The Young Man of the Name of Guppy which plainly says, "What do you come calling here for and getting ME into a row?"

"It's quite right. I gave him those directions," says my Lady. "Let the young man wait."

"By no means, my Lady. Since he has your orders to come, I will not interrupt you." Sir Leicester in his gallantry retires, rather declining to accept a bow from the young man as he goes out and majestically supposing him to be some shoemaker of intrusive appearance.

Commentary:

In this plate Phiz provides us with an idea of the resemblance between Esther Summerson and Lady Dedlock — a resemblance Guppy noticed when he saw the noblewoman's portrait during a tour of Chesney Wold. One should also note that a visitor looking at portraits in a great country house when the famiy is not in residence has an important literary precedent in Austen's Pride and Prejudice, where such a visit also moves the plot along by leading to a new understanding of a chief member of the family.

"I believe you!" says Mrs. Bagnet. "He's a Briton. That's what Woolwich is. A Briton!"

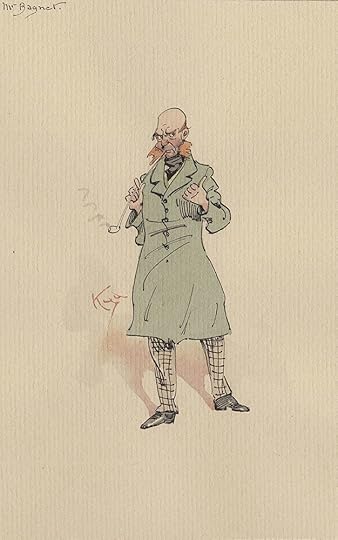

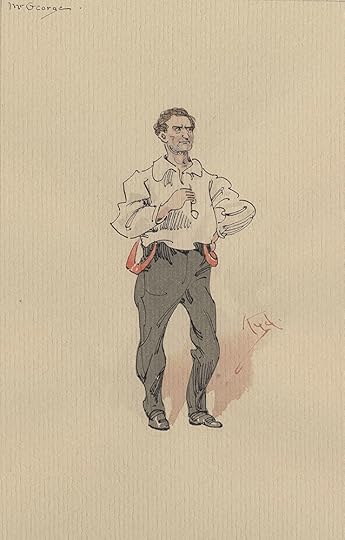

Chapter 27

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"And how's young Woolwich?" says Mr. George.

"Ah! There now!" cries Mrs. Bagnet, turning about from her saucepans (for she is cooking dinner) with a bright flush on her face. "Would you believe it? Got an engagement at the theayter, with his father, to play the fife in a military piece."

"Well done, my godson!" cries Mr. George, slapping his thigh.

"I believe you!" says Mrs. Bagnet. "He's a Briton. That's what Woolwich is. A Briton!"

"And Mat blows away at his bassoon, and you're respectable civilians one and all," says Mr. George. "Family people. Children growing up. Mat's old mother in Scotland, and your old father somewhere else, corresponded with, and helped a little, and—well, well! To be sure, I don't know why I shouldn't be wished a hundred mile away, for I have not much to do with all this!"

The Ironmaster

Chapter 28

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock, as I have already apologized for intruding on you, I cannot do better than be very brief. I thank you, Sir Leicester."

The head of the Dedlocks has motioned towards a sofa between himself and my Lady. Mr. Rouncewell quietly takes his seat there.

"In these busy times, when so many great undertakings are in progress, people like myself have so many workmen in so many places that we are always on the flight."

Sir Leicester is content enough that the ironmaster should feel that there is no hurry there; there, in that ancient house, rooted in that quiet park, where the ivy and the moss have had time to mature, and the gnarled and warted elms and the umbrageous oaks stand deep in the fern and leaves of a hundred years; and where the sun-dial on the terrace has dumbly recorded for centuries that time which was as much the property of every Dedlock—while he lasted—as the house and lands. Sir Leicester sits down in an easy-chair, opposing his repose and that of Chesney Wold to the restless flights of ironmasters.

"Lady Dedlock has been so kind," proceeds Mr. Rouncewell with a respectful glance and a bow that way, "as to place near her a young beauty of the name of Rosa. Now, my son has fallen in love with Rosa and has asked my consent to his proposing marriage to her and to their becoming engaged if she will take him—which I suppose she will. I have never seen Rosa until to-day, but I have some confidence in my son's good sense—even in love. I find her what he represents her, to the best of my judgment; and my mother speaks of her with great commendation."

Mr. Guppy's catechism

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"You have been strangely importunate. If it should appear, after all, that what you have to say does not concern me—and I don't know how it can, and don't expect that it will—you will allow me to cut you short with but little ceremony. Say what you have to say, if you please."

My Lady, with a careless toss of her screen, turns herself towards the fire again, sitting almost with her back to the young man of the name of Guppy.

"With your ladyship's permission, then," says the young man, "I will now enter on my business. Hem! I am, as I told your ladyship in my first letter, in the law. Being in the law, I have learnt the habit of not committing myself in writing, and therefore I did not mention to your ladyship the name of the firm with which I am connected and in which my standing—and I may add income—is tolerably good. I may now state to your ladyship, in confidence, that the name of that firm is Kenge and Carboy, of Lincoln's Inn, which may not be altogether unknown to your ladyship in connexion with the case in Chancery of Jarndyce and Jarndyce."

My Lady's figure begins to be expressive of some attention. She has ceased to toss the screen and holds it as if she were listening.

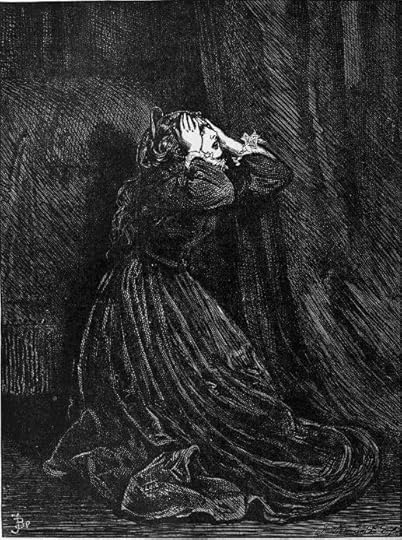

"O my child, O my child!"

Chapter 29

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

So the young man makes his bow and goes downstairs, where the supercilious Mercury does not consider himself called upon to leave his Olympus by the hall-fire to let the young man out.

As Sir Leicester basks in his library and dozes over his newspaper, is there no influence in the house to startle him, not to say to make the very trees at Chesney Wold fling up their knotted arms, the very portraits frown, the very armour stir?

No. Words, sobs, and cries are but air, and air is so shut in and shut out throughout the house in town that sounds need be uttered trumpet-tongued indeed by my Lady in her chamber to carry any faint vibration to Sir Leicester's ears; and yet this cry is in the house, going upward from a wild figure on its knees.

"O my child, my child! Not dead in the first hours of her life, as my cruel sister told me, but sternly nurtured by her, after she had renounced me and my name! O my child, O my child!"

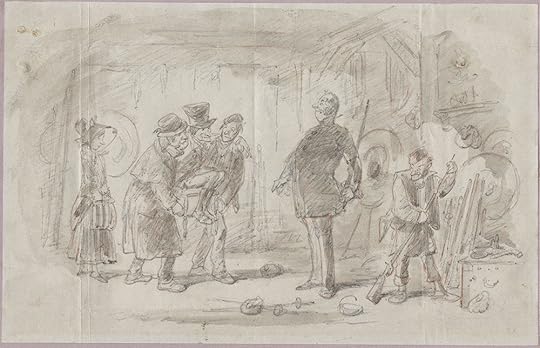

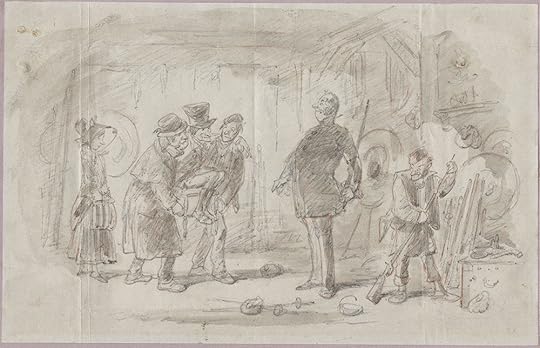

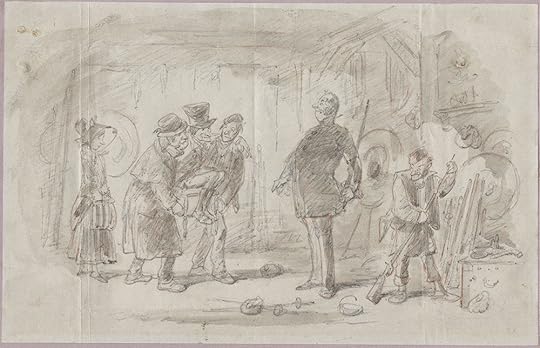

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)

Kim wrote: "

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! Like all original sketches to the final steel engraving’s imprint the image is reversed, but that’s elementary.

Let’s take a look at Mr George. In the original sketch his left hand holds a straight sword pointing upwards. He does not have a sheath for the sword. Mr George does not have a full head of hair.

In the final illustration Mr George has a sabre, not a sword and it is in Mr George’s right hand, not his left, that rests on the hilt of the sabre. It could be me, but Mr George’s face is somewhat different and he appears to have more hair.

Minor details but very interesting nevertheless. It’s endlessly fascinating to study the illustrations.

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! Like all original sketches to the final steel engraving’s imprint the image is reversed, but that’s elementary.

Let’s take a look at Mr George. In the original sketch his left hand holds a straight sword pointing upwards. He does not have a sheath for the sword. Mr George does not have a full head of hair.

In the final illustration Mr George has a sabre, not a sword and it is in Mr George’s right hand, not his left, that rests on the hilt of the sabre. It could be me, but Mr George’s face is somewhat different and he appears to have more hair.

Minor details but very interesting nevertheless. It’s endlessly fascinating to study the illustrations.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! Like all origi..."

I'm putting them together so I can study them both at the same time, I wish I could flip one of them. :-) :

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! Like all origi..."

I'm putting them together so I can study them both at the same time, I wish I could flip one of them. :-) :

Tristram wrote: "So we know that Lady Dedlock was not cruel enough to renounce her child but was a victim of her sister’s heartlessness."

Tristram wrote: "So we know that Lady Dedlock was not cruel enough to renounce her child but was a victim of her sister’s heartlessness."This took me completely by surprise, and does make me think very differently about Lady D. Poor woman. And her sister is AWFUL.

Guppy clearly is planning to blackmail her with his letters. I am very impressed with his scheming. I had to go back and look to work out who took the law-writer's letters after he died, and it looks like it was the appropriately-named Krook, and Guppy has his lodger cozying up to Krook now, so! Impressive, Guppy.

But I hate him for the way he makes Lady D beg--from "if you choose" to "if you--please." I hope Tulkinghorn catches on and smashes him. I am guessing Guppy is over his head if he thinks he can take on Tulkinghorn. Though I could be wrong. Guppy is not the type to be distracted by Allegory.

Two very lovable lines from this selection:

Two very lovable lines from this selection:"The old girl," says Mr. Bagnet in reply, "is a thoroughly fine woman. Consequently, she is like a thoroughly fine day. Gets finer as she gets on."

And:

"Pray," says Sir Leicester to Mercury, "what do you mean by announcing with this abruptness a young man of the name of Guppy?"

There was something to love on every page in this installment.

Kim wrote: "I'm putting these together too just to see if I missed anything:

"

There are a couple of tiny details that are different - or even could be the lack of definition in the sketch - but I really enjoy the final illustration. I’m looking especially at the footstools, Sir Leicester’s chair, and the side table. The detail and the curvature of the furniture are wonderfully created. What great attention to detail. Just look at how a tiny footstool peeks out from under Lady Dedlock’s dress.

"

There are a couple of tiny details that are different - or even could be the lack of definition in the sketch - but I really enjoy the final illustration. I’m looking especially at the footstools, Sir Leicester’s chair, and the side table. The detail and the curvature of the furniture are wonderfully created. What great attention to detail. Just look at how a tiny footstool peeks out from under Lady Dedlock’s dress.

Julie wrote: "Guppy clearly is planning to blackmail her with his letters. I am very impressed with his scheming."

Guppy never struck me as a blackmailer before. And I never thought he was so in love with Esther he would go through that for her. I should have remembered that everyone loves her the minute they see her and can't bear to be parted from her.

Guppy never struck me as a blackmailer before. And I never thought he was so in love with Esther he would go through that for her. I should have remembered that everyone loves her the minute they see her and can't bear to be parted from her.

Kim wrote: "Guppy never struck me as a blackmailer before. And I never thought he was so in love with Esther he would go through that for her. I should have remembered that everyone loves her the minute they see her and can't bear to be parted from her."

Kim wrote: "Guppy never struck me as a blackmailer before. And I never thought he was so in love with Esther he would go through that for her. I should have remembered that everyone loves her the minute they see her and can't bear to be parted from her."Ha! But he doesn't care about Esther. She's his angle into pots and pots of Jarndyce v Jarndyce fortune.

Or maybe now Dedlock money--probably a better bet.

Another thing I was thinking about with this installment is how glad I am that Jarndyce took a stand on Ada and Richard. He must have hated this, given that he is the most conflict-averse man ever to live, and also everyone is fond of Richard. But Richard is bad news. That part where Smallweed talks about the odds of wringing some money out of him when George says there's nothing left:

Another thing I was thinking about with this installment is how glad I am that Jarndyce took a stand on Ada and Richard. He must have hated this, given that he is the most conflict-averse man ever to live, and also everyone is fond of Richard. But Richard is bad news. That part where Smallweed talks about the odds of wringing some money out of him when George says there's nothing left: "No, no, my dear friend. No, no, Mr. George. No, no, no, sir," remonstrates Grandfather Smallweed, cunningly rubbing his spare legs. "Not quite a dead halt, I think. He has good friends, and he is good for his pay, and he is good for the selling price of his commission, and he is good for his chance in a lawsuit, and he is good for his chance in a wife, and—oh, do you know, Mr. George, I think my friend would consider the young gentleman good for something yet?" says Grandfather Smallweed, turning up his velvet cap and scratching his ear like a monkey.

There might not be a major villain in this book but there sure are a lot of people willing to step in and be as villainous as their petty capacities permit--Guppy, Smallweed, Tulkinghorn in his more stylish manner. I feel sorry for Richard here because it's clear the entire society has it out to exploit not just him but anyone who cares about him--but I'm also saddened and angry with him for his weakness in falling right into every trap that presents itself.

So, good for Jarndyce in caring more for Ada than for his own reluctance to think ill of anyone. Is this maybe a little character growth?

(Much good it will do anyone, however, since Ideal Victorian Women fall in love for life.)

Julie wrote: "Another thing I was thinking about with this installment is how glad I am that Jarndyce took a stand on Ada and Richard. He must have hated this, given that he is the most conflict-averse man ever ..."

Hi Julie

Yes. I agree with you about the range of villains and those who rub against the laws too frequently. While we don’t have a horrid arch villain in this novel we have what is perhaps even more sinister. In Bleak House we find many characters who have vices and immorality who seem to be, on the surface, not such bad people. It is only when Dickens explores such characters that we find, observe, and, at times, get to see their individual villainy in operation.

Hi Julie

Yes. I agree with you about the range of villains and those who rub against the laws too frequently. While we don’t have a horrid arch villain in this novel we have what is perhaps even more sinister. In Bleak House we find many characters who have vices and immorality who seem to be, on the surface, not such bad people. It is only when Dickens explores such characters that we find, observe, and, at times, get to see their individual villainy in operation.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! Like all origi..."

Peter,

You have a very good eye for these details! I noticed the change of weapon and of the way it was wielded. I think that the original picture was changed because the raised weapon behind Mr. George's back implies too much tension and maybe aggressiveness on the part of the ex-soldier, whereas in the novel, he comes over as a very self-confident and self-possessed man. He would have the weapon in his hand, maybe, but rest leisurely on it because he is so sure of his personal qualities and of his way through life that he would not need to brandish it in order to intimidate such a creature as Grandfather Smallweed.

Another thing about the illustrations: I have been doing this for a while now given all the different artists Kim has collected for us. I take a good look at the picture and then try to guess who made it, and I can tell a Phiz from a Barnard from a Furniss from a Peake by now. And of course, every one else from a Kyd! :-)

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! Like all origi..."

Peter,

You have a very good eye for these details! I noticed the change of weapon and of the way it was wielded. I think that the original picture was changed because the raised weapon behind Mr. George's back implies too much tension and maybe aggressiveness on the part of the ex-soldier, whereas in the novel, he comes over as a very self-confident and self-possessed man. He would have the weapon in his hand, maybe, but rest leisurely on it because he is so sure of his personal qualities and of his way through life that he would not need to brandish it in order to intimidate such a creature as Grandfather Smallweed.

Another thing about the illustrations: I have been doing this for a while now given all the different artists Kim has collected for us. I take a good look at the picture and then try to guess who made it, and I can tell a Phiz from a Barnard from a Furniss from a Peake by now. And of course, every one else from a Kyd! :-)

It's beyond a doubt by now that Guppy intends to blackmail Lady Dedlock, but still I rather like him in a way. He illustrates how a certain personality makes a person choose a certain job, and how that job then goes on to reinforce his personality in the ways it was developing anyway. Mr. Guppy is quite ambitious and knows what side his bread is buttered on. Furthermore, he is extremely mistrustful, expecting schemes and underhandedness from other people, and that's why he himself resorts to schemes, tactics and conspiracies. I do not really think that his making Lady Dedlock use the words "if you please" in order to humiliate the lady, but simply because he could not be completely sure whether he was on the right track, and by forcing her to come clean and show more interest, he could make sure that he was not barking up the wrong tree after all. Mr. Guppy would definitely be a very good chess player.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! ..."

Yes. I too love the range of illustrators that Kim provides us. It is fascinating to see how various illustrators either build from the earlier artists or provide a fresh creative picture for us.

Original Phiz drawing, something about it looks different than the final illustration but I can't figure out what it is. Peter will know though. :-)"

Hi Kim

Good eye! ..."

Yes. I too love the range of illustrators that Kim provides us. It is fascinating to see how various illustrators either build from the earlier artists or provide a fresh creative picture for us.

I think I misread Guppy. I remember watching the BBC production, which I did not finish, and somehow thought he was going to be some type of lovable hero in this story’s totality.

I think I misread Guppy. I remember watching the BBC production, which I did not finish, and somehow thought he was going to be some type of lovable hero in this story’s totality.With regard to Tristram’s comment, this is a line from Chapter 20:

“He in the most ingenious manner takes infinite pains to counterplot, when there is no plot; and plays the deepest games of chess without any adversary.”

John wrote: "“He in the most ingenious manner takes infinite pains to counterplot, when there is no plot; and plays the deepest games of chess without any adversary.”..."

John wrote: "“He in the most ingenious manner takes infinite pains to counterplot, when there is no plot; and plays the deepest games of chess without any adversary.”..."It's a great line. It gives us some insight into Guppy, but is still rather enigmatic.

John wrote: "I think I misread Guppy. I remember watching the BBC production, which I did not finish, and somehow thought he was going to be some type of lovable hero in this story’s totality.

With regard to T..."

If I am quite honest, John, I have to admit that this part of Guppy's, the tendency to play chess without an adversary, is not so alien to myself in my job life. Maybe, that is why I enjoy Guppy so much - he makes me laugh about myself.

With regard to T..."

If I am quite honest, John, I have to admit that this part of Guppy's, the tendency to play chess without an adversary, is not so alien to myself in my job life. Maybe, that is why I enjoy Guppy so much - he makes me laugh about myself.

I keep thinking that Guppy, in all of his smartness and his conniving ways, seems to just miss the point a lot of times. Just like he does not see how pathetic he makes himself when proposing to Esther and stalking her when she refuses him, he now does seem to not really make that connection to Lady Dedlock he seems to think he made. His plotting and trying to elbow his way up shows, and I think that will be his downfall - and he does not seem to notice it himself.

Jantine,

I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. Sooner or later, they get entangled in the complexities of their own thinking, Especially if their is a certain naivity at the bottom of their character - as I think there is with our friend Mr. Guppy.

I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. Sooner or later, they get entangled in the complexities of their own thinking, Especially if their is a certain naivity at the bottom of their character - as I think there is with our friend Mr. Guppy.

Tristram wrote: "I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. ..."

Tristram wrote: "I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. ..."I had to look this up, of course. It's a great concept! But as it's in French, it's a phrase I'll probably never use. The French language and I have never gotten along. Surely there must be an English equivalent?

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. ..."I had to look this up, of course. It's a great concept! But as it's in French, it's a phrase..."

I think the closest English equivalent is occupational hazard.

There is a Dutch equivalent: beroepsdeformatie

My husband has it a lot, there are times he sees computer problems everywhere :-P (he's been system administrator for 14 years, programmer, and he's now doing some other IT job)

My husband has it a lot, there are times he sees computer problems everywhere :-P (he's been system administrator for 14 years, programmer, and he's now doing some other IT job)

Tristram wrote: "Another thing about the illustrations: I have been doing this for a while now given all the different artists Kim has collected for us. I take a good look at the picture and then try to guess who made it, and I can tell a Phiz from a Barnard from a Furniss from a Peake by now. And of course, every one else from a Kyd! :-)

I am impressed! I can do the same thing, although me doing it isn't as impressive as you doing it. These things have been drilled into my brain. :-)

I am impressed! I can do the same thing, although me doing it isn't as impressive as you doing it. These things have been drilled into my brain. :-)

As for Kyd, I get to see paragraphs about him with many of his illustrations and I thought I'd share this one with you, especially you Peter. :-)

Clark had many occupations during his lifetime, including designer of cigarette cards and postcards, and as a fore-edge painter principally specializing in characters from the works of Charles Dickens. He worked for Punch for only one day and then as a freelance artist until 1900.

Clark's illustrations from Dickens first appeared in 1887 in Fleet Street Magazine, with two published collections appearing shortly after as The Characters of Charles Dickens (1889) and Some Well Known Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens (1892). Kyd's representations from the works of Dickens owe much to the original illustrations of Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz') and Robert Seymour (the first illustrator of The Pickwick Papers, one of Clark's most popular themes), while the modelling of the characters seems to be based on Phiz's later designs from the 1870s. Early in the twentieth century five sets of postcards based on his Dickens drawings were published, as well as seven sets of non-Dickensian comic cards.

I can hardly believe you missed how much Kyd and Phiz illustrations look alike. :-)

Clark had many occupations during his lifetime, including designer of cigarette cards and postcards, and as a fore-edge painter principally specializing in characters from the works of Charles Dickens. He worked for Punch for only one day and then as a freelance artist until 1900.

Clark's illustrations from Dickens first appeared in 1887 in Fleet Street Magazine, with two published collections appearing shortly after as The Characters of Charles Dickens (1889) and Some Well Known Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens (1892). Kyd's representations from the works of Dickens owe much to the original illustrations of Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz') and Robert Seymour (the first illustrator of The Pickwick Papers, one of Clark's most popular themes), while the modelling of the characters seems to be based on Phiz's later designs from the 1870s. Early in the twentieth century five sets of postcards based on his Dickens drawings were published, as well as seven sets of non-Dickensian comic cards.

I can hardly believe you missed how much Kyd and Phiz illustrations look alike. :-)

Kim wrote: "As for Kyd, I get to see paragraphs about him with many of his illustrations and I thought I'd share this one with you, especially you Peter. :-)

Clark had many occupations during his lifetime, in..."

Oh my. I wonder what Browne would say about being an inspiration for Kyd. Perhaps it’s best if we will never know. ;-)

Clark had many occupations during his lifetime, in..."

Oh my. I wonder what Browne would say about being an inspiration for Kyd. Perhaps it’s best if we will never know. ;-)

Ulysse wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I'd say that this is the déformation professionnelle of all plotters or schemers. ..."

I had to look this up, of course. It's a great concept! But as it's in Fren..."

Thanks, I didn't know there was an English word. The German word is Berufskrankheit. And it's surprisingly short for a German word.

As a teacher, I noticed that our occupational hazards are saying things at least twice, liking to explain stuff without being asked to, and interrupting people. I hope I don't interrupt people, but I have noticed that never do I get interrupted so much as when talking with colleagues.

I had to look this up, of course. It's a great concept! But as it's in Fren..."

Thanks, I didn't know there was an English word. The German word is Berufskrankheit. And it's surprisingly short for a German word.

As a teacher, I noticed that our occupational hazards are saying things at least twice, liking to explain stuff without being asked to, and interrupting people. I hope I don't interrupt people, but I have noticed that never do I get interrupted so much as when talking with colleagues.

Young man by the name of Guppy

Chapter 29

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

Sir Leicester is reading with infinite gravity and state when the door opens, and the Mercury in powder makes this strange announcement, "The young man, my Lady, of the name of Guppy."

Sir Leicester pauses, stares, repeats in a killing voice, "The young man of the name of Guppy?"

Looking round, he beholds the young man of the name of Guppy, much discomfited and not presenting a very impressive letter of introduction in his manner and appearance.

"Pray," says Sir Leicester to Mercury, "what do you mean by announcing with this abruptness a young man of the name of Guppy?"

"I beg your pardon, Sir Leicester, but my Lady said she would see the young man whenever he called. I was not aware that you were here, Sir Leicester."

With this apology, Mercury directs a scornful and indignant look at the young man of the name of Guppy which plainly says, "What do you come calling here for and getting me into a row?"

"It's quite right. I gave him those directions," says my Lady. "Let the young man wait."

"By no means, my Lady. Since he has your orders to come, I will not interrupt you." Sir Leicester in his gallantry retires, rather declining to accept a bow from the young man as he goes out and majestically supposing him to be some shoemaker of intrusive appearance.

Lady Dedlock looks imperiously at her visitor when the servant has left the room, casting her eyes over him from head to foot. She suffers him to stand by the door and asks him what he wants.

Commentary:

Guppy, believing that he has solved the mystery of Esther Summerson's (in fact, "Hawdon's] birth, now dares to visit Lady Dedlock at the couple's London townhouse. Like Jo, the crossing-sweeper, Guppy has seen the similarity between Lady Dedlock's face and Esther's, but Guppy has made his guess from studying a portrait of Sir Leicester's wife that he had seen when visiting Chesney Wold. Inferring that Lady Dedlock is in fact Esther's mother, and that her father was the recently deceased law-writer "Nemo," Guppy has pieced together such clues as Miss Barbary's being Lady Dedlock's sister (who raised Esther) and that the real identity of the impoverished, drug-addicted scrivener of Cook's Court is Captain Hawdon. He reveals that he knows that Lady Dedlock visited Hawdon's grave in disguise at Tom-all-Alone's recently, and that she gave Jo the sovereigns. In support of his contention, he proposes to bring Jo in to her identify her as the mysterious visitor. Guppy now offers to obtain the correspondence between Hawdon and his lover for Lady Dedlock to enable her to keep her liaison secret. Lady Dedlock maintains her haughty composure throughout the interview in the library, but once Guppy has gone she collapses under the weight of remorse, crying, "Oh, my child!" She had apparently not known that her sister had brought up the child she thought had died in infancy.

The Two Maids

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"I occasionally meet on my staircase here," drawls Volumnia, whose thoughts perhaps are already hopping up it to bed, after a long evening of very desultory talk, "one of the prettiest girls, I think, that I ever saw in my life."

"A protegée of my Lady's," observes Sir Leicester.

"I thought so. I felt sure that some uncommon eye must have picked that girl out. She really is a marvel. A dolly sort of beauty perhaps," says Miss Volumnia, reserving her own sort, "but in its way, perfect; such bloom I never saw!"

Sir Leicester, with his magnificent glance of displeasure at the rouge, appears to say so too.

"Indeed," remarks my Lady languidly, "if there is any uncommon eye in the case, it is Mrs. Rouncewell's, and not mine. Rosa is her discovery."

"Your maid, I suppose?"

"No. My anything; pet — secretary — messenger — I don't know what."

Earlier Passage describing Hortense:

My Lady's maid is a Frenchwoman of two and thirty, from somewhere in the southern country about Avignon and Marseilles, a large-eyed brown woman with black hair who would be handsome but for a certain feline mouth and general uncomfortable tightness of face, rendering the jaws too eager and the skull too prominent. There is something indefinably keen and wan about her anatomy, and she has a watchful way of looking out of the corners of her eyes without turning her head which could be pleasantly dispensed with, especially when she is in an ill humour and near knives. Through all the good taste of her dress and little adornments, these objections so express themselves that she seems to go about like a very neat she-wolf imperfectly tamed. Besides being accomplished in all the knowledge appertaining to her post, she is almost an Englishwoman in her acquaintance with the language; consequently, she is in no want of words to shower upon Rosa for having attracted my Lady's attention, and she pours them out with such grim ridicule as she sits at dinner that her companion, the affectionate man, is rather relieved when she arrives at the spoon stage of that performance.

Ha, ha, ha! She, Hortense, been in my Lady's service since five years and always kept at the distance, and this doll, this puppet, caressed — absolutely caressed — by my Lady on the moment of her arriving at the house! Ha, ha, ha! "And do you know how pretty you are, child?" "No, my Lady." You are right there! "And how old are you, child! And take care they do not spoil you by flattery, child!" Oh, how droll! It is the best thing altogether.