The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Bleak House

Bleak House

>

Bleak House, Chp. 39-42

Chapter 40, „National and Domestic“, takes us back to Chesney Wold, where Mrs. Rouncewell is preparing everything for the impending arrival of Sir Leicester, Lady Dedlock and the flock of hovering cousins. Once more, the narrator remarks on how light effects play with the interior of the old mansion, especially with the paintings, and Lady Dedlock’s painting again seems to be the centre of tragic irony:

”But the fire of the sun is dying. Even now the floor is dusky, and shadow slowly mounts the walls, bringing the Dedlocks down like age and death. And now, upon my Lady's picture over the great chimney-piece, a weird shade falls from some old tree, that turns it pale, and flutters it, and looks as if a great arm held a veil or hood, watching an opportunity to draw it over her. Higher and darker rises shadow on the wall—now a red gloom on the ceiling—now the fire is out.”

And here:

”Now the moon is high; and the great house, needing habitation more than ever, is like a body without life. Now it is even awful, stealing through it, to think of the live people who have slept in the solitary bedrooms, to say nothing of the dead. Now is the time for shadow, when every corner is a cavern and every downward step a pit, when the stained glass is reflected in pale and faded hues upon the floors, when anything and everything can be made of the heavy staircase beams excepting their own proper shapes, when the armour has dull lights upon it not easily to be distinguished from stealthy movement, and when barred helmets are frightfully suggestive of heads inside. But of all the shadows in Chesney Wold, the shadow in the long drawing-room upon my Lady's picture is the first to come, the last to be disturbed. At this hour and by this light it changes into threatening hands raised up and menacing the handsome face with every breath that stirs.”

Mylady is unwell – and, interestingly compared to “a bird of passage” when she was at Chesney Wold for her last visit, where she met Esther. When the Dedlocks and their retinue arrive, evenings are spent in the usual manner, and Volumnia does her best to cultivate the good-will of her noble and eminent relative. One of these evenings, when Volumia is talking about Mr. Tulkinghorn and expresses her worries about the old man working himself to death, we get this:

”It may be the gathering gloom of evening, or it may be the darker gloom within herself, but a shade is on my Lady's face, as if she thought, ‘I would he were!’”

This is the first of several allusions to Mr. Tulkinghorn’s possible ride on the sweet chariot. Finally, Mr. Tulkinghorn arrives, and both Mylady and Volumnia object to Sir Leicester’s proposal of having more light – though, probably, each for a different reason. In the course of their conversation, Mr. Tulkinghorn tells the story of a noble woman who had an illegitimate affair, and whose female servant, on it all becoming known, was tainted in the eyes of the family of her potential suitor. Lady Dedlock understands this story as a threat against her with regard to her lady’s maid Rosa, with whom Lady Dedlock has no intention of parting yet – a conversation between Sir Leicester and his wife on this question being the innocuous occasion for Mr. Tulkinghorn to share this little story with his hosts.

”But the fire of the sun is dying. Even now the floor is dusky, and shadow slowly mounts the walls, bringing the Dedlocks down like age and death. And now, upon my Lady's picture over the great chimney-piece, a weird shade falls from some old tree, that turns it pale, and flutters it, and looks as if a great arm held a veil or hood, watching an opportunity to draw it over her. Higher and darker rises shadow on the wall—now a red gloom on the ceiling—now the fire is out.”

And here:

”Now the moon is high; and the great house, needing habitation more than ever, is like a body without life. Now it is even awful, stealing through it, to think of the live people who have slept in the solitary bedrooms, to say nothing of the dead. Now is the time for shadow, when every corner is a cavern and every downward step a pit, when the stained glass is reflected in pale and faded hues upon the floors, when anything and everything can be made of the heavy staircase beams excepting their own proper shapes, when the armour has dull lights upon it not easily to be distinguished from stealthy movement, and when barred helmets are frightfully suggestive of heads inside. But of all the shadows in Chesney Wold, the shadow in the long drawing-room upon my Lady's picture is the first to come, the last to be disturbed. At this hour and by this light it changes into threatening hands raised up and menacing the handsome face with every breath that stirs.”

Mylady is unwell – and, interestingly compared to “a bird of passage” when she was at Chesney Wold for her last visit, where she met Esther. When the Dedlocks and their retinue arrive, evenings are spent in the usual manner, and Volumnia does her best to cultivate the good-will of her noble and eminent relative. One of these evenings, when Volumia is talking about Mr. Tulkinghorn and expresses her worries about the old man working himself to death, we get this:

”It may be the gathering gloom of evening, or it may be the darker gloom within herself, but a shade is on my Lady's face, as if she thought, ‘I would he were!’”

This is the first of several allusions to Mr. Tulkinghorn’s possible ride on the sweet chariot. Finally, Mr. Tulkinghorn arrives, and both Mylady and Volumnia object to Sir Leicester’s proposal of having more light – though, probably, each for a different reason. In the course of their conversation, Mr. Tulkinghorn tells the story of a noble woman who had an illegitimate affair, and whose female servant, on it all becoming known, was tainted in the eyes of the family of her potential suitor. Lady Dedlock understands this story as a threat against her with regard to her lady’s maid Rosa, with whom Lady Dedlock has no intention of parting yet – a conversation between Sir Leicester and his wife on this question being the innocuous occasion for Mr. Tulkinghorn to share this little story with his hosts.

Chapter 41 finds us „In Mr. Tulkinghorn’s Room“, i.e. in the turret chamber in which he sleeps whenever he pays a visit to Chesney Wold, whither he repairs after he has told his story. Here the narrator already gives some dark foreboding message, and some more will follow in this chapter and the next – so we might feel entitled to worry about good Mr. T.:

”The time was once when men as knowing as Mr. Tulkinghorn would walk on turret-tops in the starlight and look up into the sky to read their fortunes there. Hosts of stars are visible to-night, though their brilliancy is eclipsed by the splendour of the moon. If he be seeking his own star as he methodically turns and turns upon the leads, it should be but a pale one to be so rustily represented below. If he be tracing out his destiny, that may be written in other characters nearer to his hand.”

I don’t think that it comes as a very great surprise to him when he suddenly finds that Lady Dedlock has followed him into his room. Lady Dedlock is under emotional pressure, and Mr. Tulkinghorn cannot really decide whether she is angry or intimidated, but she soon begins the conversation by expressing her worries about any harm coming over Rosa through her. In the course of the conversation it becomes clear that Lady Dedlock has already prepared to leave Chesney Wold this very night and to leave everything behind her, her clothes, her jewelry and anything that came into her property through her marriage to Sir Leicester. She would rather disappear into oblivion than bring shame over Sir Leicester. Mr. Tulkinghorn points out to her that by running away and hiding, she would definitely bring shame over her husband because people would start asking questions. He makes it very clear to her that he has not yet come to a conclusion as to what he is going to do with the knowledge he has finally received and long suspected – how did he receive that knowledge, by the way: Were there any letters in Mr. Krook’s possession after all? – and he also points out that his sole obligation is towards Sir Leicester and the family name and interest, and that there is none obligation whatever to her.

At this point, I stopped reading and asked myself what Mr. Tulkinghorn’s motives are: Why does he not simply keep his knowledge to himself? It would not be very likely for anybody else to find out what he has found out, and so he might easily leave Lady Dedlock alone without harming Sir Leicester, might he not? Is it some abstract notion of duty that drives him on? Or does he simply enjoy the power he wields over that proud and beautiful woman? He seems to dislike women in general; after all, he says to himself that most problems are the result of marriage. How would he know? He is a bachelor. Did he have a chat with Mr. Snagsby about marriage? So, what are his motives? Mr. Tulkinghorn’s wish to prolong that state of anxiety and insecurity for Lady Dedlock not only resembles Chancery’s tendency to prolong insecurity for its litigants but it also suggests that Mr. Tulkinghorn quite enjoys his power over Lady Dedlock. At least he promises her not to take any action without giving her fair warning first.

However, he may be playing a very dangerous game there – there are at least two passages that imply danger for him, namely those:

”Their need for watching one another should be over now, but they do it all this time, and the stars watch them both through the opened window. Away in the moonlight lie the woodland fields at rest, and the wide house is as quiet as the narrow one. The narrow one! Where are the digger and the spade, this peaceful night, destined to add the last great secret to the many secrets of the Tulkinghorn existence? Is the man born yet, is the spade wrought yet? Curious questions to consider, more curious perhaps not to consider, under the watching stars upon a summer night.”

And, towards the end of the chapter:

”He would know it all the better if he saw the woman pacing her own rooms with her hair wildly thrown from her flung-back face, her hands clasped behind her head, her figure twisted as if by pain. He would think so all the more if he saw the woman thus hurrying up and down for hours, without fatigue, without intermission, followed by the faithful step upon the Ghost's Walk. But he shuts out the now chilled air, draws the window-curtain, goes to bed, and falls asleep. And truly when the stars go out and the wan day peeps into the turret-chamber, finding him at his oldest, he looks as if the digger and the spade were both commissioned and would soon be digging.”

”The time was once when men as knowing as Mr. Tulkinghorn would walk on turret-tops in the starlight and look up into the sky to read their fortunes there. Hosts of stars are visible to-night, though their brilliancy is eclipsed by the splendour of the moon. If he be seeking his own star as he methodically turns and turns upon the leads, it should be but a pale one to be so rustily represented below. If he be tracing out his destiny, that may be written in other characters nearer to his hand.”

I don’t think that it comes as a very great surprise to him when he suddenly finds that Lady Dedlock has followed him into his room. Lady Dedlock is under emotional pressure, and Mr. Tulkinghorn cannot really decide whether she is angry or intimidated, but she soon begins the conversation by expressing her worries about any harm coming over Rosa through her. In the course of the conversation it becomes clear that Lady Dedlock has already prepared to leave Chesney Wold this very night and to leave everything behind her, her clothes, her jewelry and anything that came into her property through her marriage to Sir Leicester. She would rather disappear into oblivion than bring shame over Sir Leicester. Mr. Tulkinghorn points out to her that by running away and hiding, she would definitely bring shame over her husband because people would start asking questions. He makes it very clear to her that he has not yet come to a conclusion as to what he is going to do with the knowledge he has finally received and long suspected – how did he receive that knowledge, by the way: Were there any letters in Mr. Krook’s possession after all? – and he also points out that his sole obligation is towards Sir Leicester and the family name and interest, and that there is none obligation whatever to her.

At this point, I stopped reading and asked myself what Mr. Tulkinghorn’s motives are: Why does he not simply keep his knowledge to himself? It would not be very likely for anybody else to find out what he has found out, and so he might easily leave Lady Dedlock alone without harming Sir Leicester, might he not? Is it some abstract notion of duty that drives him on? Or does he simply enjoy the power he wields over that proud and beautiful woman? He seems to dislike women in general; after all, he says to himself that most problems are the result of marriage. How would he know? He is a bachelor. Did he have a chat with Mr. Snagsby about marriage? So, what are his motives? Mr. Tulkinghorn’s wish to prolong that state of anxiety and insecurity for Lady Dedlock not only resembles Chancery’s tendency to prolong insecurity for its litigants but it also suggests that Mr. Tulkinghorn quite enjoys his power over Lady Dedlock. At least he promises her not to take any action without giving her fair warning first.

However, he may be playing a very dangerous game there – there are at least two passages that imply danger for him, namely those:

”Their need for watching one another should be over now, but they do it all this time, and the stars watch them both through the opened window. Away in the moonlight lie the woodland fields at rest, and the wide house is as quiet as the narrow one. The narrow one! Where are the digger and the spade, this peaceful night, destined to add the last great secret to the many secrets of the Tulkinghorn existence? Is the man born yet, is the spade wrought yet? Curious questions to consider, more curious perhaps not to consider, under the watching stars upon a summer night.”

And, towards the end of the chapter:

”He would know it all the better if he saw the woman pacing her own rooms with her hair wildly thrown from her flung-back face, her hands clasped behind her head, her figure twisted as if by pain. He would think so all the more if he saw the woman thus hurrying up and down for hours, without fatigue, without intermission, followed by the faithful step upon the Ghost's Walk. But he shuts out the now chilled air, draws the window-curtain, goes to bed, and falls asleep. And truly when the stars go out and the wan day peeps into the turret-chamber, finding him at his oldest, he looks as if the digger and the spade were both commissioned and would soon be digging.”

We are leaving Chesney Wold with Chapter 42, which opens „In Mr. Tulkinghorn’s Chambers” and sees us back to London. First of all, we learn more about Mr. Tulkinghorn’s view on mankind when the narrator makes the following wry comment:

”Like a dingy London bird among the birds at roost in these pleasant fields, where the sheep are all made into parchment, the goats into wigs, and the pasture into chaff, the lawyer, smoke-dried and faded, dwelling among mankind but not consorting with them, aged without experience of genial youth, and so long used to make his cramped nest in holes and corners of human nature that he has forgotten its broader and better range, comes sauntering home. In the oven made by the hot pavements and hot buildings, he has baked himself dryer than usual; and he has in his thirsty mind his mellowed port-wine half a century old.”

By the way, note the bird imagery! It seems to suggest that the lawyer’s profession may be responsible for his bleak and scornful attitude towards human beings in general. Mr. Tulkinghorn, on returning home, runs into Mr. Snagsby, whose worries are not over yet. The stationer tells his best customer that he has been beleaguered for some time by Lady Dedlock’s former maid-servant. Mlle Hortense, who has again and again tried to find Mr. Tulkinghorn at home and has repeatedly been denied access to him, has taken recourse to pestering the second person in line, much to Mr. Snagsby’s chagrin, who fears that his wife’s jealousy will be aroused again. Mr. Tulkinghorn tells Mr. Snagsby to send Mlle Hortense to his place when she appears next time. When he finally enters his chambers, he does this – as a man of keys:

”So saying, he unlocks his door, gropes his way into his murky rooms, lights his candles, and looks about him. It is too dark to see much of the Allegory overhead there, but that importunate Roman, who is for ever toppling out of the clouds and pointing, is at his old work pretty distinctly. Not honouring him with much attention, Mr. Tulkinghorn takes a small key from his pocket, unlocks a drawer in which there is another key, which unlocks a chest in which there is another, and so comes to the cellar-key, with which he prepares to descend to the regions of old wine. He is going towards the door with a candle in his hand when a knock comes.”

Then he has another, a female visitor, this time Mlle Hortense. The Frenchwoman thinks that Mr. Tulkinghorn has behaved meanly and shabbily towards her, trying to fob her off with two sovereigns, which she flings into his office, full of scorn. She makes it clear that she does not believe her appearance was all about a simple wager and she avows her hatred of Lady Dedlock and offers herself as his accomplice in bringing the Lady down. Mr. Tulkinghorn is not interested. When he finds Mlle Hortense adamant, he tells her that if she pesters him or Mr. Snagsby once more, he will see to it that she is taken to prison but Mlle Hortense is hardly impressed by this threat and promises to dare Mr. Tulkinghorn. By the way, I find it quite impressive how Dickens has Mlle Hortense speak English; you would really think that the French language is the basis of her speech; cf this bit:

”’Yes. What is it that I tell you? You know you have. You have attrapped me—catched me—to give you information; you have asked me to show you the dress of mine my Lady must have wore that night, you have prayed me to come in it here to meet that boy. Say! Is it not?‘ Mademoiselle Hortense makes another spring.“

We have the wrong form “catched” and words like “attraped” and “prayed”, which might be misapplied by a French-speaking person who would be thinking of words like “attraper quelqu’un” or “prier quelqu’un”. Even in these details, Dickens is masterful.

”Like a dingy London bird among the birds at roost in these pleasant fields, where the sheep are all made into parchment, the goats into wigs, and the pasture into chaff, the lawyer, smoke-dried and faded, dwelling among mankind but not consorting with them, aged without experience of genial youth, and so long used to make his cramped nest in holes and corners of human nature that he has forgotten its broader and better range, comes sauntering home. In the oven made by the hot pavements and hot buildings, he has baked himself dryer than usual; and he has in his thirsty mind his mellowed port-wine half a century old.”

By the way, note the bird imagery! It seems to suggest that the lawyer’s profession may be responsible for his bleak and scornful attitude towards human beings in general. Mr. Tulkinghorn, on returning home, runs into Mr. Snagsby, whose worries are not over yet. The stationer tells his best customer that he has been beleaguered for some time by Lady Dedlock’s former maid-servant. Mlle Hortense, who has again and again tried to find Mr. Tulkinghorn at home and has repeatedly been denied access to him, has taken recourse to pestering the second person in line, much to Mr. Snagsby’s chagrin, who fears that his wife’s jealousy will be aroused again. Mr. Tulkinghorn tells Mr. Snagsby to send Mlle Hortense to his place when she appears next time. When he finally enters his chambers, he does this – as a man of keys:

”So saying, he unlocks his door, gropes his way into his murky rooms, lights his candles, and looks about him. It is too dark to see much of the Allegory overhead there, but that importunate Roman, who is for ever toppling out of the clouds and pointing, is at his old work pretty distinctly. Not honouring him with much attention, Mr. Tulkinghorn takes a small key from his pocket, unlocks a drawer in which there is another key, which unlocks a chest in which there is another, and so comes to the cellar-key, with which he prepares to descend to the regions of old wine. He is going towards the door with a candle in his hand when a knock comes.”

Then he has another, a female visitor, this time Mlle Hortense. The Frenchwoman thinks that Mr. Tulkinghorn has behaved meanly and shabbily towards her, trying to fob her off with two sovereigns, which she flings into his office, full of scorn. She makes it clear that she does not believe her appearance was all about a simple wager and she avows her hatred of Lady Dedlock and offers herself as his accomplice in bringing the Lady down. Mr. Tulkinghorn is not interested. When he finds Mlle Hortense adamant, he tells her that if she pesters him or Mr. Snagsby once more, he will see to it that she is taken to prison but Mlle Hortense is hardly impressed by this threat and promises to dare Mr. Tulkinghorn. By the way, I find it quite impressive how Dickens has Mlle Hortense speak English; you would really think that the French language is the basis of her speech; cf this bit:

”’Yes. What is it that I tell you? You know you have. You have attrapped me—catched me—to give you information; you have asked me to show you the dress of mine my Lady must have wore that night, you have prayed me to come in it here to meet that boy. Say! Is it not?‘ Mademoiselle Hortense makes another spring.“

We have the wrong form “catched” and words like “attraped” and “prayed”, which might be misapplied by a French-speaking person who would be thinking of words like “attraper quelqu’un” or “prier quelqu’un”. Even in these details, Dickens is masterful.

Chapter 39: I wrote about unwholesome sheep being mentioned. It might be the times, in which people are called sheep too often, but I had to think about how it must be unwholesome sheep who find themselves in Voles' office while he's waiting until they die and he can pick the last bits of whatever he wants from them like the vulture he is. Also, 'what about'-isms are still used to shut up people with plans and ideas for change.

There is a loose surface of soot everywhere, that is a bad sign at all times. It reminds me of Krook's combustion, and there's Guppy talking about combustion too.

There is a loose surface of soot everywhere, that is a bad sign at all times. It reminds me of Krook's combustion, and there's Guppy talking about combustion too.

Chapter 40: And now I wonder what I never wondered before. In this part about Chesney Wold and the Dedlocks it almost seems like the omnicient narrator attaches themselves to Chesney Wold like they are one of the Dedlocks. Or at least like someone who belongs there, on the same line of leaving a gap when leaving the place. It makes me wonder who the omnicient narrator would be.

Volumnia seems to lay bare something vital: everyone important seems to rely on Tulkinhorn for everything - and so she ruffles Sir Leicester's feathers a bit.

Did others notice the whole part about how Lady Dedlock seemed to think 'I wish he were dead', and then just before Tulkinhorn enters there is a gun shot, and Lady Dedlock says something along the lines of 'it's just a rat, and they shot him'. We all know who she might see as a rat that would better be shot at that point ... and that person walks in the sentence right after.

Volumnia seems to lay bare something vital: everyone important seems to rely on Tulkinhorn for everything - and so she ruffles Sir Leicester's feathers a bit.

Did others notice the whole part about how Lady Dedlock seemed to think 'I wish he were dead', and then just before Tulkinhorn enters there is a gun shot, and Lady Dedlock says something along the lines of 'it's just a rat, and they shot him'. We all know who she might see as a rat that would better be shot at that point ... and that person walks in the sentence right after.

Jantine wrote: "Did others notice the whole part about how Lady Dedlock seemed to think 'I wish he were dead', and then just before Tulkinhorn enters there is a gun shot, and Lady Dedlock says something along the lines of 'it's just a rat, and they shot him'. We all know who she might see as a rat that would better be shot at that point ... and that person walks in the sentence right after."

Jantine wrote: "Did others notice the whole part about how Lady Dedlock seemed to think 'I wish he were dead', and then just before Tulkinhorn enters there is a gun shot, and Lady Dedlock says something along the lines of 'it's just a rat, and they shot him'. We all know who she might see as a rat that would better be shot at that point ... and that person walks in the sentence right after."Yes. That was pretty good. Especially since she's worried he'll rat her out.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 41 finds us „In Mr. Tulkinghorn’s Room“, i.e. in the turret chamber in which he sleeps whenever he pays a visit to Chesney Wold, whither he repairs after he has told his story. Here the nar..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 41 finds us „In Mr. Tulkinghorn’s Room“, i.e. in the turret chamber in which he sleeps whenever he pays a visit to Chesney Wold, whither he repairs after he has told his story. Here the nar..."I very much enjoyed this chapter for a number of reasons. I felt Dickens was thoroughly in charge. There's a lot of plot and suspense happening, but also the detail and description are just perfect. In addition to all the passages Tristram pointed to (that ominous digger and spade!), I particularly liked this line: "Perhaps there is a rather increased sense of power upon him as he loosely grasps one of his veinous wrists with his other hand and holding it behind his back walks noiselessly up and down."

Here's one place where I felt the description tripped, however, and I am noticing it especially because Peter has made me so aware of all the looking into glasses in this book:

As he paces the leads with his eyes most probably as high above his thoughts as they are high above the earth, he is suddenly stopped in passing the window by two eyes that meet his own. The ceiling of his room is rather low; and the upper part of the door, which is opposite the window, is of glass. There is an inner baize door, too, but the night being warm he did not close it when he came upstairs. These eyes that meet his own are looking in through the glass from the corridor outside. He knows them well. The blood has not flushed into his face so suddenly and redly for many a long year as when he recognizes Lady Dedlock.

The reason I think the writing doesn't quite work here (which is unusual in this chapter) is that I had to read it over and over before I could figure out what was going on. She's just looking at him through a window in his door, right? But there's *so* much detail about how this happens that it's confusing: why do we need to know the height of his ceiling, or that the door is lined up with the window, or that there's an inner baize door, whatever that is?

I bring it up because of Peter's mirrors and glasses theme, and because Dickens seems to be laboring very, very hard to keep it before us here, maybe harder than he ought to, and I wonder why.

Also another reason I enjoyed this chapter is I feel vindicated in thinking Lady D is looking out for her husband and not just for herself: she's ready to take off on her own with nothing to spare him, and Tulkinghorn keeps her under his power by threatening to hurt Sir L's reputation. I guess it's her reputation too, but I still think her primary concern here is not to hurt two of the very few people who have cared for her: Rosa and Sir L.

Also another reason I enjoyed this chapter is I feel vindicated in thinking Lady D is looking out for her husband and not just for herself: she's ready to take off on her own with nothing to spare him, and Tulkinghorn keeps her under his power by threatening to hurt Sir L's reputation. I guess it's her reputation too, but I still think her primary concern here is not to hurt two of the very few people who have cared for her: Rosa and Sir L. Also what is it with Dickens and people angling for power over haughty women? (view spoiler) Is there any biographical precedent for this? From what little I know of them, neither poor Catherine Hogarth nor young Ellen Ternan seem like that type. Maybe he's just fantasizing.

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Tulkinghorn is not interested. When he finds Mlle Hortense adamant, he tells her that if she pesters him or Mr. Snagsby once more, he will see to it that she is taken to prison."

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Tulkinghorn is not interested. When he finds Mlle Hortense adamant, he tells her that if she pesters him or Mr. Snagsby once more, he will see to it that she is taken to prison."Tulkinghorn! You're so rude to people who don't have anything you want.

Also it is fascinating how carefully this man locks up his liquor.

Jantine wrote: "Chapter 39: I wrote about unwholesome sheep being mentioned. It might be the times, in which people are called sheep too often, but I had to think about how it must be unwholesome sheep who find th..."

Jantine, I interpreted the "sheep" reference as meaning parchment. Was parchment not made from sheep skins?

Jantine, I interpreted the "sheep" reference as meaning parchment. Was parchment not made from sheep skins?

Jantine wrote: "Chapter 40: And now I wonder what I never wondered before. In this part about Chesney Wold and the Dedlocks it almost seems like the omnicient narrator attaches themselves to Chesney Wold like they..."

I found this another typical Dickensian coincidence played out for dramatic effect - something I quite enjoy. At the same time I wondered who might shoot at a rat? It would take a lot of skill to expedite a rat via bullet, leaving alone all the time you would have to wait for the rat to appear. I am sure they put up traps for rats at Chesney Wold like everyone else does.

I found this another typical Dickensian coincidence played out for dramatic effect - something I quite enjoy. At the same time I wondered who might shoot at a rat? It would take a lot of skill to expedite a rat via bullet, leaving alone all the time you would have to wait for the rat to appear. I am sure they put up traps for rats at Chesney Wold like everyone else does.

Julie wrote: "Also it is fascinating how carefully this man locks up his liquor. "

I ought to do that, too.

I ought to do that, too.

Re: Peter's earlier observation of Dicken's use of hands in the narrative, I noticed this quote from Vholes in discussing Richard's legal claims:

Re: Peter's earlier observation of Dicken's use of hands in the narrative, I noticed this quote from Vholes in discussing Richard's legal claims:You brought them with clean hands, sir, and I accepted them with clean hands.

Clean hands can become dirty so easily.

This line summed up one theme of the book for me:

It is a justification to him in his own eyes to have an embodied antagonist and oppressor.

It refers to Richard's antagonism towards John, but there are so many in our story who are the personification of the evils of Chancery -- Tulkinghorn, Vholes, Krook, et al, and their victims, Miss Flite, the man from Shropshire, Ada and -- Richard? Interestingly, while the quote is referring to John, he seems to be the only one who has risen above this suit and refuses to be either a victim or victimizer.

Tristram wrote: "it also suggests that Mr. Tulkinghorn quite enjoys his power over Lady Dedlock..."

I don't know where Tulkinghorn's misogyny started, but I think you've hit the nail on the head, here, Tristram. This is all about power over a woman, and if it somehow serves his client, as well, that's icing on the cake.

As for the rat, even the four-legged kind can be quite large, and an easy target for someone used to, say, hunting squirrels, if they're not on the run.

Tristram wrote: " I find it quite impressive how Dickens has Mlle Hortense speak English.... Even in these details, Dickens is masterful...."

Tristram wrote: " I find it quite impressive how Dickens has Mlle Hortense speak English.... Even in these details, Dickens is masterful...."While reading this exchange, I was also taken with the amazing casting of these two characters in the 2005 BBC adaptation of the book. Charles Dance and Lilo Baur were perfect as Tulkinghorn and Hortense, and in my mind I heard Dickens words coming from the two of them. It's all I can do to wait until we finish the book to watch this again.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

this week’s instalment was by far more enjoyable to me than last week’s because the omniscient narrator with his penchant for satire is back. And so is Mr. Tulkinghorn, who actua..."

Well, we certainly get our fill with lawyers in this chapter from the very successful to the very needy. But the law is the law, and its one great principle is to make business for itself. I certainly can see Vholes as being a major factor in Richard’s increasing dislike of Mr Jarndyce. Skimpole is definitely another factor of Richard’s change of heart. Clearly, Richard, unlike Esther, did not learn his lesson earlier in the novel when Skimpole first extracted money from Richard.

this week’s instalment was by far more enjoyable to me than last week’s because the omniscient narrator with his penchant for satire is back. And so is Mr. Tulkinghorn, who actua..."

Well, we certainly get our fill with lawyers in this chapter from the very successful to the very needy. But the law is the law, and its one great principle is to make business for itself. I certainly can see Vholes as being a major factor in Richard’s increasing dislike of Mr Jarndyce. Skimpole is definitely another factor of Richard’s change of heart. Clearly, Richard, unlike Esther, did not learn his lesson earlier in the novel when Skimpole first extracted money from Richard.

Mary Lou wrote: "As for the rat, even the four-legged kind can be quite large, and an easy target for someone used to, say, hunting squirrels, if they're not on the run."

Mary Lou wrote: "As for the rat, even the four-legged kind can be quite large, and an easy target for someone used to, say, hunting squirrels, if they're not on the run."Seconding Mary Lou. We had a rat problem one summer. They were so bold they would come out in the yard and run around the grass in broad daylight while we were eating dinner on the back porch, and too smart for traps, so my teenaged son borrowed his grandfather's air rifle with some success, and he doesn't even hunt squirrels.

Anyway now we have a dog who handles it.

Funny the things that come up on this forum.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 41 finds us „In Mr. Tulkinghorn’s Room“, i.e. in the turret chamber in which he sleeps whenever he pays a visit to Chesney Wold, whither he repairs after he has told his story. Here the nar..."

To me, Tulkinghorn is a man who enjoys wielding power. On the one hand, he knows that Dedlock would follow his lawyer’s suggestions. On the other hand, Tulkinghorn revels in the power he holds over Lady Dedlock. She is nothing more than a mouse, and he is the cat. We have already noticed how cats and mice are set within this week’s discourse. Like a cat, Tulkinghorn is in no hurry to bring Lady Dedlock to ground. One cannot savour a victory when that victory comes in haste.

Like the fine alcohol Tulkinghorn has locked away, its taste enjoyed all the more by keeping it under lock and key, Lady Dedlock’s demise must be savoured.

To me, Tulkinghorn is a man who enjoys wielding power. On the one hand, he knows that Dedlock would follow his lawyer’s suggestions. On the other hand, Tulkinghorn revels in the power he holds over Lady Dedlock. She is nothing more than a mouse, and he is the cat. We have already noticed how cats and mice are set within this week’s discourse. Like a cat, Tulkinghorn is in no hurry to bring Lady Dedlock to ground. One cannot savour a victory when that victory comes in haste.

Like the fine alcohol Tulkinghorn has locked away, its taste enjoyed all the more by keeping it under lock and key, Lady Dedlock’s demise must be savoured.

Peter wrote: "I certainly can see Vholes as being a major factor in Richard’s increasing dislike of Mr Jarndyce."

Peter wrote: "I certainly can see Vholes as being a major factor in Richard’s increasing dislike of Mr Jarndyce."A vole is kind of like a rat.

Cuter, though.

Mary Lou wrote: "This line summed up one theme of the book for me:

Mary Lou wrote: "This line summed up one theme of the book for me: It is a justification to him in his own eyes to have an embodied antagonist and oppressor.

It refers to Richard's antagonism towards John, but there are so many in our story who are the personification of the evils of Chancery -- Tulkinghorn, Vholes, Krook, et al, and their victims, Miss Flite, the man from Shropshire, Ada and -- Richard? Interestingly, while the quote is referring to John, he seems to be the only one who has risen above this suit and refuses to be either a victim or victimizer. "

What a great point.

Peter wrote: "Like the fine alcohol Tulkinghorn has locked away, its taste enjoyed all the more by keeping it under lock and key, Lady Dedlock’s demise must be savoured."

Peter wrote: "Like the fine alcohol Tulkinghorn has locked away, its taste enjoyed all the more by keeping it under lock and key, Lady Dedlock’s demise must be savoured."Ahhhhh. I get it now.

Julie wrote: "A vole is kind of like a rat. Cuter though."

Julie wrote: "A vole is kind of like a rat. Cuter though."Much cuter. But point taken. :-)

If Tulkinghorn is the rat, Vholes is the smaller - dare I say "mousier"? - vole. Still an invasive rodent, but somehow not as bold or repugnant.

Tristram wrote: "We are leaving Chesney Wold with Chapter 42, which opens „In Mr. Tulkinghorn’s Chambers” and sees us back to London. First of all, we learn more about Mr. Tulkinghorn’s view on mankind when the nar..."

Hortense is again referred to as “a tigerish expansion” and she threatens Tulkinghorn by “stretching out her hand.” Tulkinghorn tells Hortense that what “I say, I mean; and what I threaten, I will do, mistress.” With that exchange Hortense leaves and Tulkinghorn returns “to the leisurely enjoyment” of a “cob-webbed bottle.” Now symbolically, I see the cob-webbed bottle as representing the historical Dedlock name that Tulkinghorn plans to bring to its knees.

What I find most interesting - and ominous - is the fact that Dickens ends the chapter with yet another reference to the “Roman pointing from the ceiling.” The presence of a hand comes again into play, and it is pointing. The question is to whom or towards what is the finger pointing? Where will Fate land?

Hortense is again referred to as “a tigerish expansion” and she threatens Tulkinghorn by “stretching out her hand.” Tulkinghorn tells Hortense that what “I say, I mean; and what I threaten, I will do, mistress.” With that exchange Hortense leaves and Tulkinghorn returns “to the leisurely enjoyment” of a “cob-webbed bottle.” Now symbolically, I see the cob-webbed bottle as representing the historical Dedlock name that Tulkinghorn plans to bring to its knees.

What I find most interesting - and ominous - is the fact that Dickens ends the chapter with yet another reference to the “Roman pointing from the ceiling.” The presence of a hand comes again into play, and it is pointing. The question is to whom or towards what is the finger pointing? Where will Fate land?

Tristram wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Chapter 39: I wrote about unwholesome sheep being mentioned. It might be the times, in which people are called sheep too often, but I had to think about how it must be unwholesome s..."

It came from the candles, because they were mutton fat candles. It's just a bit further. I got a very strong symbolic feeling from it though.

It came from the candles, because they were mutton fat candles. It's just a bit further. I got a very strong symbolic feeling from it though.

Tristram wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Chapter 40: And now I wonder what I never wondered before. In this part about Chesney Wold and the Dedlocks it almost seems like the omnicient narrator attaches themselves to Chesne..."

Exactly. Traps, there's special dogs with vicious maws who fit into the holes too ... I don't think it's usual to shoot rats. Meanwhile the whole paragraph, no, the whole chapter is basically about Tulkinghorn. Warning, big spoiler: (view spoiler) and very much busy ratting Lady D out.

Exactly. Traps, there's special dogs with vicious maws who fit into the holes too ... I don't think it's usual to shoot rats. Meanwhile the whole paragraph, no, the whole chapter is basically about Tulkinghorn. Warning, big spoiler: (view spoiler) and very much busy ratting Lady D out.

Never knew what a vole was; interesting. There is currently a rash of moles in my neighborhood. I feel bad for the moles, though. The neighborhood took what was their home.

Never knew what a vole was; interesting. There is currently a rash of moles in my neighborhood. I feel bad for the moles, though. The neighborhood took what was their home.

Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "As for the rat, even the four-legged kind can be quite large, and an easy target for someone used to, say, hunting squirrels, if they're not on the run."

Seconding Mary Lou. We ha..."

I never knew that gunning rats could be an efficient means against them but here in Germany it is probably forbidden anyway.

Seconding Mary Lou. We ha..."

I never knew that gunning rats could be an efficient means against them but here in Germany it is probably forbidden anyway.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "I certainly can see Vholes as being a major factor in Richard’s increasing dislike of Mr Jarndyce."

A vole is kind of like a rat.

Cuter, though."

I hate rodents. All of them. Cute or not although I can't imagine seeing a cute one. They are on my list of why did you make these God? A few years ago the things got into our garage. While there they decided to do not nice things to some of our Christmas decorations which inspired me to do some not nice things to them. I was complaining of having mice in our garage at choir practice one night and one of the ladies asked if I was sure it was mice or could it be voles. I told her I had no idea and never heard of a vole. She asked if they had webbed feet and short tails. I said I am getting nowhere near enough to see if they have webbed feet and short tails. Eventually we killed them all, we didn't see anymore anyway and I still don't know if their feet were webbed. Either way I hate them.

A vole is kind of like a rat.

Cuter, though."

I hate rodents. All of them. Cute or not although I can't imagine seeing a cute one. They are on my list of why did you make these God? A few years ago the things got into our garage. While there they decided to do not nice things to some of our Christmas decorations which inspired me to do some not nice things to them. I was complaining of having mice in our garage at choir practice one night and one of the ladies asked if I was sure it was mice or could it be voles. I told her I had no idea and never heard of a vole. She asked if they had webbed feet and short tails. I said I am getting nowhere near enough to see if they have webbed feet and short tails. Eventually we killed them all, we didn't see anymore anyway and I still don't know if their feet were webbed. Either way I hate them.

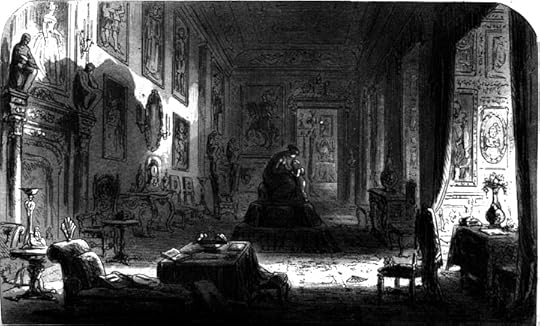

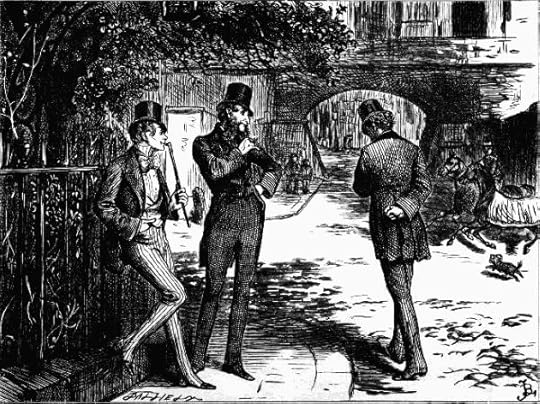

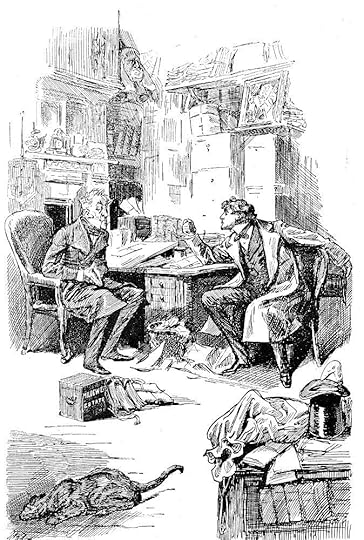

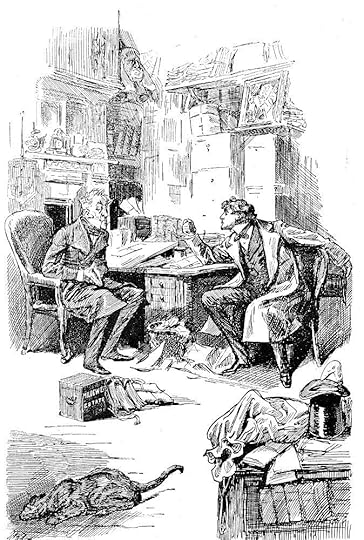

"Attorney and Client: Fortitude and Impatience"

Chapter 39

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Vholes, sitting with his arms on the desk, quietly bringing the tips of his five right fingers to meet the tips of his five left fingers, and quietly separating them again, and fixedly and slowly looking at his client, replies, "A good deal is doing, sir. We have put our shoulders to the wheel, Mr. Carstone, and the wheel is going round."

"Yes, with Ixion on it. How am I to get through the next four or five accursed months?" exclaims the young man, rising from his chair and walking about the room.

"Mr. C.," returns Vholes, following him close with his eyes wherever he goes, "your spirits are hasty, and I am sorry for it on your account. Excuse me if I recommend you not to chafe so much, not to be so impetuous, not to wear yourself out so. You should have more patience. You should sustain yourself better."

"I ought to imitate you, in fact, Mr. Vholes?" says Richard, sitting down again with an impatient laugh and beating the devil's tattoo with his boot on the patternless carpet.

"Sir," returns Vholes, always looking at the client as if he were making a lingering meal of him with his eyes as well as with his professional appetite. "Sir," returns Vholes with his inward manner of speech and his bloodless quietude, "I should not have had the presumption to propose myself as a model for your imitation or any man's. Let me but leave the good name to my three daughters, and that is enough for me; I am not a self-seeker. But since you mention me so pointedly, I will acknowledge that I should like to impart to you a little of my — come, sir, you are disposed to call it insensibility, and I am sure I have no objection — say insensibility — a little of my insensibility."

"Mr. Vholes," explains the client, somewhat abashed, "I had no intention to accuse you of insensibility."

"I think you had, sir, without knowing it," returns the equable Vholes. "Very naturally. It is my duty to attend to your interests with a cool head, and I can quite understand that to your excited feelings I may appear, at such times as the present, insensible. My daughters may know me better; my aged father may know me better. But they have known me much longer than you have, and the confiding eye of affection is not the distrustful eye of business. Not that I complain, sir, of the eye of business being distrustful; quite the contrary. In attending to your interests, I wish to have all possible checks upon me; it is right that I should have them; I court inquiry. But your interests demand that I should be cool and methodical, Mr. Carstone; and I cannot be otherwise — no, sir, not even to please you."

Commentary:

On a first look it seems that this illustration contains a simple representation of a moment in the narrative: Richard sits, looking anxious and distracted, whilst Vholes prevaricates, with a world-weary expression on his face. It is interesting to note that the two characters are not caricatured, and in Dickens and Phiz Michael Steig has noted that Phiz's illustrations for Bleak House move away from caricature towards a darker, more naturalistic type of illustration. Richard in particular still looks rather idealized — he is very pretty, with almost feminine features, emphasizing his youth and perhaps linking him with Ada and Esther, the other wards of Jarndyce — but his expression does a good job of evoking his frustration and desperation.

The title, however, rather than suggesting simply the naturalistic illustration of a confrontation in the text, calls to mind the satirical work of William Hogarth and such oppositions as "Industry and Idleness". We are therefore encouraged by this accompanying text to look for more emblematic details within the illustration. Some examples are; the cat and mouse (mentioned in Dickens' text) suggesting Richard's position under threat from Vholes, and the spider webs on the wall, suggesting, as Steig points out, the law's delay, but also possibly suggesting another image of Richard caught in Vholes' web, unable to extricate himself and waiting to be consumed by the Chancery case.

Dickens' text seems to justify such a treatment — his description of Richard in this scene reads that he is: "half sighing and half groaning; rests his aching head upon his hand, and looks the portrait of Young Despair." Richard is described as an allegorical type, justifying such further emblematic developments as the spider's web in the illustration. In fact these elements also fulfill a simple descriptive function, as Dickens mentions that the office has a "congenial shabbiness" and is dusty and dirty. Such details as the spider's web are therefore simultaneously both naturalistic and emblematic, and thus the illustration works on at least two different levels.

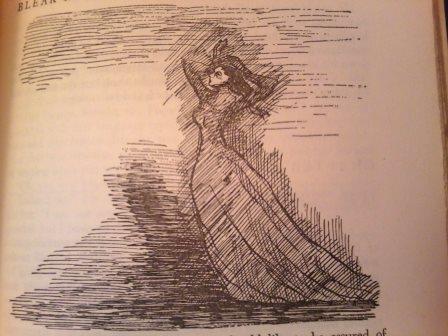

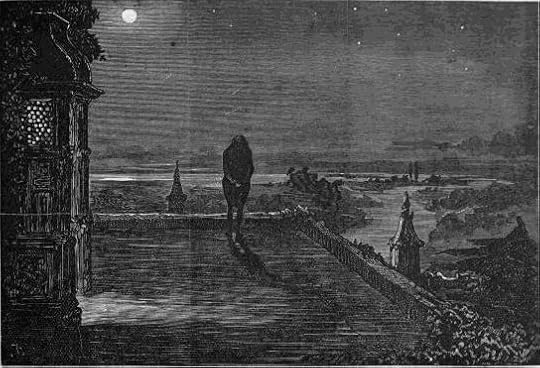

"Sunset in The long drawing-room at Chesney Wold"

Chapter 40

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"This present summer evening, as the sun goes down, the preparations are complete. Dreary and solemn the old house looks, with so many appliances of habitation and with no inhabitants except the pictured forms upon the walls. So did these come and go, a Dedlock in possession might have ruminated passing along; so did they see this gallery hushed and quiet, as I see it now; so think, as I think, of the gap that they would make in this domain when they were gone; so find it, as I find it, difficult to believe that it could be without them; so pass from my world, as I pass from theirs, now closing the reverberating door; so leave no blank to miss them, and so die.

Through some of the fiery windows beautiful from without, and set, at this sunset hour, not in dull-grey stone but in a glorious house of gold, the light excluded at other windows pours in rich, lavish, overflowing like the summer plenty in the land. Then do the frozen Dedlocks thaw. Strange movements come upon their features as the shadows of leaves play there. A dense justice in a corner is beguiled into a wink. A staring baronet, with a truncheon, gets a dimple in his chin. Down into the bosom of a stony shepherdess there steals a fleck of light and warmth that would have done it good a hundred years ago. One ancestress of Volumnia, in high- heeled shoes, very like her — casting the shadow of that virgin event before her full two centuries — shoots out into a halo and becomes a saint. A maid of honour of the court of Charles the Second, with large round eyes (and other charms to correspond), seems to bathe in glowing water, and it ripples as it glows.

But the fire of the sun is dying. Even now the floor is dusky, and shadow slowly mounts the walls, bringing the Dedlocks down like age and death. And now, upon my Lady's picture over the great chimney- piece, a weird shade falls from some old tree, that turns it pale, and flutters it, and looks as if a great arm held a veil or hood, watching an opportunity to draw it over her. Higher and darker rises shadow on the wall — now a red gloom on the ceiling — now the fire is out.

All that prospect, which from the terrace looked so near, has moved solemnly away and changed — not the first nor the last of beautiful things that look so near and will so change — into a distant phantom. Light mists arise, and the dew falls, and all the sweet scents in the garden are heavy in the air. Now the woods settle into great masses as if they were each one profound tree. And now the moon rises to separate them, and to glimmer here and there in horizontal lines behind their stems, and to make the avenue a pavement of light among high cathedral arches fantastically broken.

Now the moon is high; and the great house, needing habitation more than ever, is like a body without life. Now it is even awful, stealing through it, to think of the live people who have slept in the solitary bedrooms, to say nothing of the dead. Now is the time for shadow, when every corner is a cavern and every downward step a pit, when the stained glass is reflected in pale and faded hues upon the floors, when anything and everything can be made of the heavy staircase beams excepting their own proper shapes, when the armour has dull lights upon it not easily to be distinguished from stealthy movement, and when barred helmets are frightfully suggestive of heads inside. But of all the shadows in Chesney Wold, the shadow in the long drawing-room upon my Lady's picture is the first to come, the last to be disturbed. At this hour and by this light it changes into threatening hands raised up and menacing the handsome face with every breath that stirs."

Oh, here is a commentary on the above illustration, I ran out of room in the first post.

"In his analysis of Phiz's plate Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold Michael Steig observes:

"So strong are the effects of tone, perspective, composition, and the feeling that nonhuman forces are in control, that one is liable to overlook the fact that this illustration conveys its thematic emphases by means of methods as emblematic as those of its companion plate. Dickens provides in his text the central emblematic conception by dwelling upon the threatening shadow that encroaches upon the portrait of Lady Dedlock, and this in turn becomes the subject of the plate. But Phiz has added a central emblem, a large statue which gives the plate a focus distinct from the portrait and the shadow, and which complements them. It depicts a woman seated with a winged infant leaning upon her knee and looking up at her. In general terms this probably embodies the idea of motherly love, but its likely source in Thorwaldsen's sculpture of Venus and Cupid makes it possible to be more specific: in Thorwaldsen's piece, Venus is consoling Cupid for the bee sting he has just received, and the application at this stage of the novel would be not only to Esther's parentage, but to Lady Dedlock's failure to mother her, and to prevent her suffering as a young child."

Persuasive as this analysis is, Steig's speculations regarding the function and meaning of the statue seem rather narrow. He completely disregards the erotic undercurrents in the scene; traditionally, Venus tells Cupid that if he finds the bee's sting painful he should imagine how his own sting will afflict humankind. Lady Dedlock's tragedy is arguably brought about by love's sting in her affair with Captain Hawdon, and Esther's miserable childhood and lack of a mother figure is a direct consequence of this unhappy union. The yoking of a scene of motherly affection with the sense of threat from erotic love is particularly poignant in this context. It also might figure, rather than simply Lady Dedlock's failure to be a mother, her yearning to be so -- as is also seen in her interaction with Rosa and in the brief meeting with Esther in which she reveals her identity.

Indeed, the dim lighting in this illustration makes the statue appear less like a cold stone artifact and more like it could be an actual mother and child. This blurring between artistic representation and actual human life reduces the judgmental quality that Steig seeks to attach to the statue; the initial confusion that is possible regarding whether or not the statue might be a real mother and child reduces its ability to function as an ironic comment upon the action and folds it into the drama itself, operating as an expression of the maternal care that is thwarted in the novel but emphasizing the presence of that care just as much as it reminds us of the impossibility of its fulfillment.

A similar naturalization might be argued to function with regard to the shadow. Steig points out that the emblematic function of this shadow encroaching onto Lady Dedlock's portrait can easily be overlooked -- the overall atmosphere of the illustration is so strong that it is easy to see the shadow as an expression of that atmosphere, rather than directly symbolic of the doom approaching Lady Dedlock. Within the context of the other so-called 'dark' plates, in which the shadows and the night have no particular symbolic function, it is easy to overlook the more pointed nature of this particular shadow. Darkness is so pervasive in these more naturalistic plates that it ceases to be symbolic and becomes simply a feature of their composition."

If all that means I may have missed a shadow heading for the portrait of Lady Dedlock, the man who wrote the commentary is right, I missed it, that and many other things they mention in these commentaries.

"In his analysis of Phiz's plate Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold Michael Steig observes:

"So strong are the effects of tone, perspective, composition, and the feeling that nonhuman forces are in control, that one is liable to overlook the fact that this illustration conveys its thematic emphases by means of methods as emblematic as those of its companion plate. Dickens provides in his text the central emblematic conception by dwelling upon the threatening shadow that encroaches upon the portrait of Lady Dedlock, and this in turn becomes the subject of the plate. But Phiz has added a central emblem, a large statue which gives the plate a focus distinct from the portrait and the shadow, and which complements them. It depicts a woman seated with a winged infant leaning upon her knee and looking up at her. In general terms this probably embodies the idea of motherly love, but its likely source in Thorwaldsen's sculpture of Venus and Cupid makes it possible to be more specific: in Thorwaldsen's piece, Venus is consoling Cupid for the bee sting he has just received, and the application at this stage of the novel would be not only to Esther's parentage, but to Lady Dedlock's failure to mother her, and to prevent her suffering as a young child."

Persuasive as this analysis is, Steig's speculations regarding the function and meaning of the statue seem rather narrow. He completely disregards the erotic undercurrents in the scene; traditionally, Venus tells Cupid that if he finds the bee's sting painful he should imagine how his own sting will afflict humankind. Lady Dedlock's tragedy is arguably brought about by love's sting in her affair with Captain Hawdon, and Esther's miserable childhood and lack of a mother figure is a direct consequence of this unhappy union. The yoking of a scene of motherly affection with the sense of threat from erotic love is particularly poignant in this context. It also might figure, rather than simply Lady Dedlock's failure to be a mother, her yearning to be so -- as is also seen in her interaction with Rosa and in the brief meeting with Esther in which she reveals her identity.

Indeed, the dim lighting in this illustration makes the statue appear less like a cold stone artifact and more like it could be an actual mother and child. This blurring between artistic representation and actual human life reduces the judgmental quality that Steig seeks to attach to the statue; the initial confusion that is possible regarding whether or not the statue might be a real mother and child reduces its ability to function as an ironic comment upon the action and folds it into the drama itself, operating as an expression of the maternal care that is thwarted in the novel but emphasizing the presence of that care just as much as it reminds us of the impossibility of its fulfillment.

A similar naturalization might be argued to function with regard to the shadow. Steig points out that the emblematic function of this shadow encroaching onto Lady Dedlock's portrait can easily be overlooked -- the overall atmosphere of the illustration is so strong that it is easy to see the shadow as an expression of that atmosphere, rather than directly symbolic of the doom approaching Lady Dedlock. Within the context of the other so-called 'dark' plates, in which the shadows and the night have no particular symbolic function, it is easy to overlook the more pointed nature of this particular shadow. Darkness is so pervasive in these more naturalistic plates that it ceases to be symbolic and becomes simply a feature of their composition."

If all that means I may have missed a shadow heading for the portrait of Lady Dedlock, the man who wrote the commentary is right, I missed it, that and many other things they mention in these commentaries.

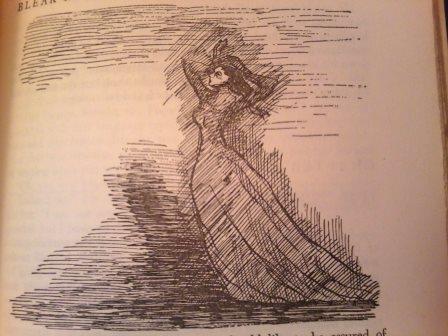

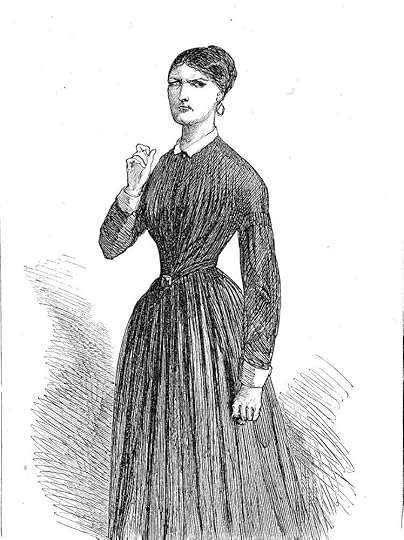

This is Ed Gorey's illustration of Lady Dedlock from Chapter 41:

Text Illustrated:

"He would know it all the better if he saw the woman pacing her own rooms with her hair wildly thrown from her flung-back face, her hands clasped behind her head, her figure twisted as if by pain. He would think so all the more if he saw the woman thus hurrying up and down for hours, without fatigue, without intermission, followed by the faithful step upon the Ghost's Walk. But he shuts out the now chilled air, draws the window-curtain, goes to bed, and falls asleep. And truly when the stars go out and the wan day peeps into the turret-chamber, finding him at his oldest, he looks as if the digger and the spade were both commissioned and would soon be digging."

Text Illustrated:

"He would know it all the better if he saw the woman pacing her own rooms with her hair wildly thrown from her flung-back face, her hands clasped behind her head, her figure twisted as if by pain. He would think so all the more if he saw the woman thus hurrying up and down for hours, without fatigue, without intermission, followed by the faithful step upon the Ghost's Walk. But he shuts out the now chilled air, draws the window-curtain, goes to bed, and falls asleep. And truly when the stars go out and the wan day peeps into the turret-chamber, finding him at his oldest, he looks as if the digger and the spade were both commissioned and would soon be digging."

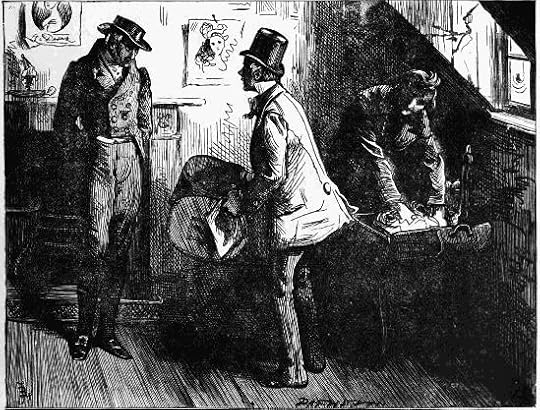

Chapter 39

Fred Barnard:

Text Illustrated:

"No doubt, no doubt." Mr. Tulkinghorn is as imperturbable as the hearthstone to which he has quietly walked. "The matter is not of that consequence that I need put you to the trouble of making any conditions, Mr. Guppy." He pauses here to smile, and his smile is as dull and rusty as his pantaloons. "You are to be congratulated, Mr. Guppy; you are a fortunate young man, sir."

Chapter 39

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Is Richard a monster in all this, or would Chancery be found rich in such precedents too if they could be got for citation from the Recording Angel?

Two pairs of eyes not unused to such people look after him, as, biting his nails and brooding, he crosses the square and is swallowed up by the shadow of the southern gateway. Mr. Guppy and Mr. Weevle are the possessors of those eyes, and they have been leaning in conversation against the low stone parapet under the trees. He passes close by them, seeing nothing but the ground.

"William," says Mr. Weevle, adjusting his whiskers, "there's combustion going on there! It's not a case of spontaneous, but it's smouldering combustion it is."

"Ah!" says Mr. Guppy. "He wouldn't keep out of Jarndyce, and I suppose he's over head and ears in debt. I never knew much of him. He was as high as the monument when he was on trial at our place. A good riddance to me, whether as clerk or client!"

Chapter 40

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"he opens the French window and steps out upon the leads. There he again walks slowly up and down in the same attitude, subsiding, if a man so cool may have any need to subside, from the story he has related downstairs.

The time was once when men as knowing as Mr. Tulkinghorn would walk on turret-tops in the starlight and look up into the sky to read their fortunes there. Hosts of stars are visible to-night, though their brilliancy is eclipsed by the splendour of the moon. If he be seeking his own star as he methodically turns and turns upon the leads, it should be but a pale one to be so rustily represented below. If he be tracing out his destiny, that may be written in other characters nearer to his hand."

Chapter 42

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Why, it matters this much, mistress," says the lawyer, deliberately putting away his handkerchief and adjusting his frill; "the law is so despotic here that it interferes to prevent any of our good English citizens from being troubled, even by a lady's visits against his desire. And on his complaining that he is so troubled, it takes hold of the troublesome lady and shuts her up in prison under hard discipline. Turns the key upon her, mistress." Illustrating with the cellar-key.

"Truly?" returns mademoiselle in the same pleasant voice. "That is droll! But—my faith!—still what does it matter to me?"

"My fair friend," says Mr. Tulkinghorn, "make another visit here, or at Mr. Snagsby's, and you shall learn."

"In that case you will send me to the prison, perhaps?"

"Perhaps."

Kim wrote: "

"Attorney and Client: Fortitude and Impatience"

Chapter 39

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Vholes, sitting with his arms on the desk, quietly bringing the tips of his five right fingers to meet the t..."

Thanks for showing this illustration Kim. As noted, the emblematic touches of the cat at the mouse hole and the spiders’ webs, while tucked away in the overall illustration, show the care and focus Phiz put into his work for the reader/viewer.

"Attorney and Client: Fortitude and Impatience"

Chapter 39

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Vholes, sitting with his arms on the desk, quietly bringing the tips of his five right fingers to meet the t..."

Thanks for showing this illustration Kim. As noted, the emblematic touches of the cat at the mouse hole and the spiders’ webs, while tucked away in the overall illustration, show the care and focus Phiz put into his work for the reader/viewer.

Kim wrote: "Here are two earlier versions of the illustration:

"

In the final version of the illustration Browne leaned heavily on the use of chiaroscuro to establish the mood. A great touch and another addition to the collection of dark plates that exist within this novel.

"

In the final version of the illustration Browne leaned heavily on the use of chiaroscuro to establish the mood. A great touch and another addition to the collection of dark plates that exist within this novel.

Kim wrote: "Oh, here is a commentary on the above illustration, I ran out of room in the first post.

"In his analysis of Phiz's plate Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold Michael Steig observes:

"..."

Hi Kim

We all bring our own ideas to any painting. I’m not sure any of us can possibly come to terms with, let alone understand and thus accurately interpret, what any work of art means. I guess there can be a consensus, but I think that’s about it.

I don’t “get” modern art or the art of many other cultures. I guess when I boil down what I do like and want from a picture is for it to tell me a story.

"In his analysis of Phiz's plate Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold Michael Steig observes:

"..."

Hi Kim

We all bring our own ideas to any painting. I’m not sure any of us can possibly come to terms with, let alone understand and thus accurately interpret, what any work of art means. I guess there can be a consensus, but I think that’s about it.

I don’t “get” modern art or the art of many other cultures. I guess when I boil down what I do like and want from a picture is for it to tell me a story.

Kim wrote: "

Chapter 42

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Why, it matters this much, mistress," says the lawyer, deliberately putting away his handkerchief and adjusting his frill; "the law is so despotic he..."

I really like this collection of Barnard illustrations. They are brooding, suggestive, and well presented.

After looking at the illustrations this week I’m asking myself how much of Bleak House is either set indoors, indoors at night, or outdoors at night. The Boythorn estate is described as bright and cheerful, as is Bleak House and the park overlooking Bleak House. That said, there seems to be much physical darkness in this novel to parallel the dark tone and mood of the story.

Chapter 42

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"Why, it matters this much, mistress," says the lawyer, deliberately putting away his handkerchief and adjusting his frill; "the law is so despotic he..."

I really like this collection of Barnard illustrations. They are brooding, suggestive, and well presented.

After looking at the illustrations this week I’m asking myself how much of Bleak House is either set indoors, indoors at night, or outdoors at night. The Boythorn estate is described as bright and cheerful, as is Bleak House and the park overlooking Bleak House. That said, there seems to be much physical darkness in this novel to parallel the dark tone and mood of the story.

Kim wrote: "Here is an early illustration of Richard and Mr. Vholes. I can barely see the thing.

"

It is interesting, and conclusive, that Phiz eventually chose the illustration which has Richard sitting at the other side of Mr. Vholes's desk, which is, as we learn, a rock. Richard's turning away from Vholes, as in the discarded version, could easily imply that he will be able to free himself from the attorney's web ...

"

It is interesting, and conclusive, that Phiz eventually chose the illustration which has Richard sitting at the other side of Mr. Vholes's desk, which is, as we learn, a rock. Richard's turning away from Vholes, as in the discarded version, could easily imply that he will be able to free himself from the attorney's web ...

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "Oh, here is a commentary on the above illustration, I ran out of room in the first post.

"In his analysis of Phiz's plate Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold Michael Steig ..."

Neither do I get modern art, Peter. Everything within me screams, "Keep it, keep it!"

"In his analysis of Phiz's plate Sunset in the Long Drawing-Room at Chesney Wold Michael Steig ..."

Neither do I get modern art, Peter. Everything within me screams, "Keep it, keep it!"

Peter wrote: "the emblematic touches of the cat at the mouse hole and the spiders’ webs, while tucked away in the overall illustration, show the care and focus Phiz put into his work for the reader/viewer...."

Peter wrote: "the emblematic touches of the cat at the mouse hole and the spiders’ webs, while tucked away in the overall illustration, show the care and focus Phiz put into his work for the reader/viewer...."This is true, Peter, and when such detail is pointed out, I appreciate that. But so often with Phiz, I never notice it on my own, and even when it is pointed out, I often have to do a little searching before I can find it. :-(

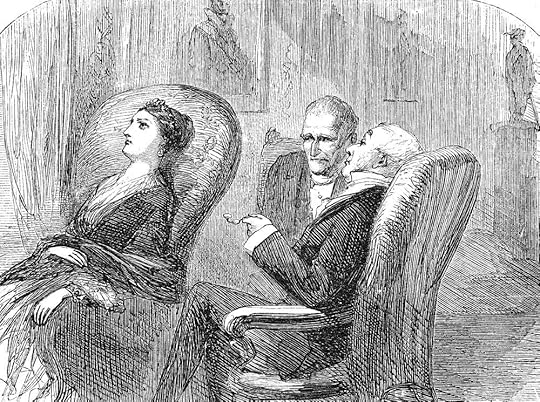

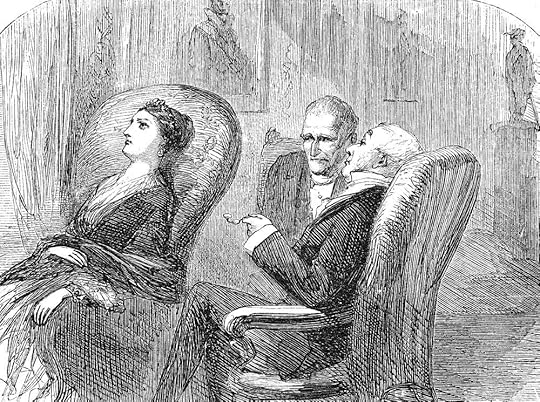

I just found a few illustrations by Sol Eytinge Jr. I missed before. Here is the one for this installment:

Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock and Mr. Tulkinghorn

Chapter 40

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Text Illustrated:

There is not much conversation in all, for late hours have been kept at Chesney Wold since the necessary expenses elsewhere began, and this is the first night in many on which the family have been alone. It is past ten when Sir Leicester begs Mr. Tulkinghorn to ring for candles. Then the stream of moonlight has swelled into a lake, and then Lady Dedlock for the first time moves, and rises, and comes forward to a table for a glass of water. Winking cousins, bat-like in the candle glare, crowd round to give it; Volumnia (always ready for something better if procurable) takes another, a very mild sip of which contents her; Lady Dedlock, graceful, self-possessed, looked after by admiring eyes, passes away slowly down the long perspective by the side of that nymph, not at all improving her as a question of contrast.

Commentary:

Eytinge had at his disposal only sixteen plates for each Diamond Edition volume, so that for longer novels such as Martin Chuzzlewit and Bleak House he had to show many of the named characters in couples and triads, and, sometimes, when material permitted, larger groups, as in the instance of Trooper George and Bagnets. For the fifty-three named characters in Bleak House by using his strategy of portraying characters in family groups and personal affiliations Eytinge was able to offer individual and group portraits of thirty-five characters. It must have been was obvious to Eytinge that he would have to show the foreigner and social isolate Hortense by herself, for she thinks only of herself and takes nobody else into her confidence. The same, in fact, might be said of the cunning lawyer Tulkinghorn, although he does have an alliance of sorts with Grandfather Smallweed. The choice of showing the prop and pillar of the aristocratic establishment with the Dedlocks was therefore a reasonable compromise; this grouping also permits Eytinge to compel readers to reflect on the fact that both Lady Dedlock and Tulkinghorn are withholding information from Sir Leicester, in part to protect and in part to protect themselves.

Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock and Mr. Tulkinghorn

Chapter 40

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Text Illustrated:

There is not much conversation in all, for late hours have been kept at Chesney Wold since the necessary expenses elsewhere began, and this is the first night in many on which the family have been alone. It is past ten when Sir Leicester begs Mr. Tulkinghorn to ring for candles. Then the stream of moonlight has swelled into a lake, and then Lady Dedlock for the first time moves, and rises, and comes forward to a table for a glass of water. Winking cousins, bat-like in the candle glare, crowd round to give it; Volumnia (always ready for something better if procurable) takes another, a very mild sip of which contents her; Lady Dedlock, graceful, self-possessed, looked after by admiring eyes, passes away slowly down the long perspective by the side of that nymph, not at all improving her as a question of contrast.

Commentary:

Eytinge had at his disposal only sixteen plates for each Diamond Edition volume, so that for longer novels such as Martin Chuzzlewit and Bleak House he had to show many of the named characters in couples and triads, and, sometimes, when material permitted, larger groups, as in the instance of Trooper George and Bagnets. For the fifty-three named characters in Bleak House by using his strategy of portraying characters in family groups and personal affiliations Eytinge was able to offer individual and group portraits of thirty-five characters. It must have been was obvious to Eytinge that he would have to show the foreigner and social isolate Hortense by herself, for she thinks only of herself and takes nobody else into her confidence. The same, in fact, might be said of the cunning lawyer Tulkinghorn, although he does have an alliance of sorts with Grandfather Smallweed. The choice of showing the prop and pillar of the aristocratic establishment with the Dedlocks was therefore a reasonable compromise; this grouping also permits Eytinge to compel readers to reflect on the fact that both Lady Dedlock and Tulkinghorn are withholding information from Sir Leicester, in part to protect and in part to protect themselves.

Mademoiselle Hortense

Chapter 42

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Text Illustrated:

"Now, mistress," says the lawyer, tapping the key hastily upon the chimney-piece. "If you have anything to say, say it, say it."

"Sir, you have not use me well. You have been mean and shabby."

"Mean and shabby, eh?" returns the lawyer, rubbing his nose with the key.

"Yes. What is it that I tell you? You know you have. You have attrapped me —catched me — to give you information; you have asked me to show you the dress of mine my Lady must have wore that night, you have prayed me to come in it here to meet that boy. Say! Is it not?" Mademoiselle Hortense makes another spring.

"You are a vixen, a vixen!" Mr. Tulkinghorn seems to meditate as he looks distrustfully at her, then he replies, "Well, wench, well. I paid you."

"You paid me!" she repeats with fierce disdain. "Two sovereign! I have not change them, I re-fuse them, I des-pise them, I throw them from me!" Which she literally does, taking them out of her bosom as she speaks and flinging them with such violence on the floor that they jerk up again into the light before they roll away into corners and slowly settle down there after spinning vehemently.

"Now!" says Mademoiselle Hortense, darkening her large eyes again. "You have paid me? Eh, my God, oh yes!"

Mr. Tulkinghorn rubs his head with the key while she entertains herself with a sarcastic laugh.

"You must be rich, my fair friend," he composedly observes, "to throw money about in that way!"

"I am rich," she returns. "I am very rich in hate. I hate my Lady, of all my heart. You know that."

Commentary:

My Lady's maid is a Frenchwoman of two and thirty, from somewhere in the southern country about Avignon and Marseilles, a large-eyed brown woman with black hair who would be handsome but for a certain feline mouth and general uncomfortable tightness of face, rendering the jaws too eager and the skull too prominent. There is something indefinably keen and wan about her anatomy, and she has a watchful way of looking out of the corners of her eyes without turning her head which could be pleasantly dispensed with, especially when she is in an ill humour and near knives. Through all the good taste of her dress and little adornments, these objections so express themselves that she seems to go about like a very neat she-wolf imperfectly tamed. Besides being accomplished in all the knowledge appertaining to her post, she is almost an Englishwoman in her acquaintance with the language; consequently, she is in no want of words to shower upon Rosa for having attracted my Lady's attention, and she pours them out with such grim ridicule as she sits at dinner that her companion, the affectionate man, is rather relieved when she arrives at the spoon stage of that performance.