The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 1, Chp. 19-22

Chapter 20 is titled "Moving in Society" and we find Tip still out of debtors prison - barely I'm guessing - and working as a billiard marker. Now since this didn't sound like much of a job to me, it didn't even sound like a person, I looked it up and found that at one time it was a quite popular job, especially for young teenage boys. In searching for information on the billiard marker I found this:

October 1875 THE ETIQUETTE OF THE BILLIARD ROOM

"When two gentlemen are playing at billiards, they are supposed to hire, not only the table, but the room, and the services of the marker. They pay a certain sum per game, or per hour, for these items, and they are, for the time being, fairly entitled to the uninterrupted use or each and all. The marker is their especial servant, and his duty is to mark the game, hand the rest, take the balls out of the pocket when a hazard is made, and act as referee if required. A marker who attends to the game can do nothing else at the same time. This being the case, we yet find in many billiard-rooms, and even in some clubs, that a gentleman will enter the room, at once call off the marker's attention from the game, and order him to get a brandy-and-soda, or beer, or change for a sovereign, and be quite unaware that he is committing as great a breach of etiquette as though he entered your dining-room and ordered your attending servant to run a message for him.

If you are compelled to employ the marker in any way, you should first ask the players if they have any objection to your marking the game whilst the marker does this or that for you; you then mark with care, hand the rest, &c., just as would the marker whose services the players are paying for. Such a proceeding is not only etiquette, it is justice.

It is the marker's duty, at the slightest hint from the players that noise or chaff is objectionable, to strike his rest on the floor so as to attract the attention of the visitors, and call, "Order, if you please, gentlemen." Such a proceeding will in almost every case produce the desired result, unless there are roughs in the room, or those who ignore all courtesy or etiquette; and when such should be present, the sooner they are taught manners the better for them, and the more agreeable for the law-loving company."

Billiards must have been quite the game if it gets its own rules of etiquette, so perhaps Tip will make a good living as a billiard marker, in the case of Tip though, I doubt it. And now we know how to be billiard markers should we ever want to give it a try. We are told of Tip that "he had troubled himself so little as to the means of his release, that Clennam scarcely needed to have been at the pains of impressing the mind of Mr Plornish on that subject." He does respect and admire his sister Amy, but not enough to change any of his behavior even knowing how it worries her. We're told:

"The same rank Marshalsea flavour was to be recognised in his distinctly perceiving that she sacrificed her life to her father, and in his having no idea that she had done anything for himself."

So much for billiard marking, now we are all able to go and be one if we so desire. One morning Little Dorrit goes on a visit to her sister. She finds that both Fanny and her uncle have already gone to the theater where they are both working, something unknown to William, how to do it anyway. Little Dorrit follows them to the theater and once there is directed to her sister by some men standing at the door:

"On her applying to them, reassured by this resemblance, for a direction to Miss Dorrit, they made way for her to enter a dark hall—it was more like a great grim lamp gone out than anything else—where she could hear the distant playing of music and the sound of dancing feet. A man so much in want of airing that he had a blue mould upon him, sat watching this dark place from a hole in a corner, like a spider; and he told her that he would send a message up to Miss Dorrit by the first lady or gentleman who went through. The first lady who went through had a roll of music, half in her muff and half out of it, and was in such a tumbled condition altogether, that it seemed as if it would be an act of kindness to iron her. But as she was very good-natured, and said, 'Come with me; I'll soon find Miss Dorrit for you,' Miss Dorrit's sister went with her, drawing nearer and nearer at every step she took in the darkness to the sound of music and the sound of dancing feet.

At last they came into a maze of dust, where a quantity of people were tumbling over one another, and where there was such a confusion of unaccountable shapes of beams, bulkheads, brick walls, ropes, and rollers, and such a mixing of gaslight and daylight, that they seemed to have got on the wrong side of the pattern of the universe."

Fanny is astonished to see Amy there asking her how she had found her way there and saying it was so strange seeing her here among the professionals. She goes on to say that little quiet things like Amy can find there way any place and that she would have never been able to do it even though she knew so much more of the world. The narrator tells us:

"It was the family custom to lay it down as family law, that she was a plain domestic little creature, without the great and sage experience of the rest. This family fiction was the family assertion of itself against her services. Not to make too much of them."

Amy tells her sister she has come because she wants to know more about the lady who gave Fanny a bracelet, she has not been quite easy since Fanny told her. They are interrupted as Fanny is called to a dance rehearsal but finally the girls involved in the dance return and begin to get ready to go home. As Fanny and Amy leave they must call to their uncle who is waiting for them in an obscure corner. We're told that even though he is waiting for his niece she still must call for him three or four times before he knows they are there. I want to know more about their uncle, how he got the way he is. I wonder if he was like Amy when he was young. They leave their uncle at a restaurant for his dinner and Fanny then takes her sister to meet Mrs. Merdle, the woman who gave her the bracelet. The woman lives at Harley Street, Cavendish Square in the grandest house on the street. When Fanny knocks on the door it is opened by a footman with powder on his head, backed up by two more footmen with powder on their heads. This gets us to bird reference for Peter:

"Fanny walked in, taking her sister with her; and they went up-stairs with powder going before and powder stopping behind, and were left in a spacious semicircular drawing-room, one of several drawing-rooms, where there was a parrot on the outside of a golden cage holding on by its beak, with its scaly legs in the air, and putting itself into many strange upside-down postures. This peculiarity has been observed in birds of quite another feather, climbing upon golden wires."

I think having a pet bird would drive me insane. Little Dorrit finds them in a room much more splendid than she ever imagined before. Mrs. Merdle enters the room and is described this way:

"The lady was not young and fresh from the hand of Nature, but was young and fresh from the hand of her maid. She had large unfeeling handsome eyes, and dark unfeeling handsome hair, and a broad unfeeling handsome bosom, and was made the most of in every particular. Either because she had a cold, or because it suited her face, she wore a rich white fillet tied over her head and under her chin. And if ever there were an unfeeling handsome chin that looked as if, for certain, it had never been, in familiar parlance, 'chucked' by the hand of man, it was the chin curbed up so tight and close by that laced bridle."

Fanny tells Mrs. Merdle that Amy is curious about her, so she decided to bring her and asks Mrs. Merdle to tell Amy how they happened to know each other. Mrs. Merdle agrees and explains that her husband is very wealthy and his influence is very great and she also has a twenty-three year old son. Her son is a gay little thing, very impressionable and had a fascination with the stage. Because of this he became fascinated by Fanny and even wanted to marry her. This distressed his mother, who went to Fanny to try to end the relationship but found that Fanny had already refused to marry him. Fanny had told Mrs. Merdle that her family's standings in the society in which her father moves is superior to the Merdle's and is acknowledged by everyone. She doesn't bother to tell her where this society her father moves in is or why it is superior. I wish she'd tell me. Mrs. Merdle who is still very concerned about their society’s prejudices had then made it clear to Fanny that any marriage between Fanny and the Merdle's son would cause them to have nothing to do with their son and would leave him a beggar. She had then given Fanny the bracelet as a mark of her appreciation. She also puts something into Fanny's hand as they leave.

As they leave Fanny asks Amy what she thinks and Amy says she is very sorry Fanny took any gifts from Mrs. Merdle. Fanny scorns Amy’s lack of self respect saying she would let herself and her family be trodden on. Mrs. Merdle looks down on them and the least they can do is to make her pay for it. Fanny then goes on to tell Amy that if she despises her sister for being a dancer than why did she make her one? It is Amy's fault she is a dancer in the first place and looked down upon by Mrs. Merdle and people like her. I suppose she does have a point there. Fanny tells her that while she has been shut up, Fanny has been out in society and has become proud and spirited and that while Amy has been thinking of dinner and clothing she has been thinking of the family's honor. Here is our ending:

'Especially as we know,' said Fanny, 'that there certainly is a tone in the place to which you have been so true, which does belong to it, and which does make it different from other aspects of Society. So kiss me once again, Amy dear, and we will agree that we may both be right, and that you are a tranquil, domestic, home-loving, good girl.'

The clarionet had been lamenting most pathetically during this dialogue, but was cut short now by Fanny's announcement that it was time to go; which she conveyed to her uncle by shutting up his scrap of music, and taking the clarionet out of his mouth.

Little Dorrit parted from them at the door, and hastened back to the Marshalsea. It fell dark there sooner than elsewhere, and going into it that evening was like going into a deep trench. The shadow of the wall was on every object. Not least upon the figure in the old grey gown and the black velvet cap, as it turned towards her when she opened the door of the dim room.

'Why not upon me too!' thought Little Dorrit, with the door yet in her hand. 'It was not unreasonable in Fanny.'

October 1875 THE ETIQUETTE OF THE BILLIARD ROOM

"When two gentlemen are playing at billiards, they are supposed to hire, not only the table, but the room, and the services of the marker. They pay a certain sum per game, or per hour, for these items, and they are, for the time being, fairly entitled to the uninterrupted use or each and all. The marker is their especial servant, and his duty is to mark the game, hand the rest, take the balls out of the pocket when a hazard is made, and act as referee if required. A marker who attends to the game can do nothing else at the same time. This being the case, we yet find in many billiard-rooms, and even in some clubs, that a gentleman will enter the room, at once call off the marker's attention from the game, and order him to get a brandy-and-soda, or beer, or change for a sovereign, and be quite unaware that he is committing as great a breach of etiquette as though he entered your dining-room and ordered your attending servant to run a message for him.

If you are compelled to employ the marker in any way, you should first ask the players if they have any objection to your marking the game whilst the marker does this or that for you; you then mark with care, hand the rest, &c., just as would the marker whose services the players are paying for. Such a proceeding is not only etiquette, it is justice.

It is the marker's duty, at the slightest hint from the players that noise or chaff is objectionable, to strike his rest on the floor so as to attract the attention of the visitors, and call, "Order, if you please, gentlemen." Such a proceeding will in almost every case produce the desired result, unless there are roughs in the room, or those who ignore all courtesy or etiquette; and when such should be present, the sooner they are taught manners the better for them, and the more agreeable for the law-loving company."

Billiards must have been quite the game if it gets its own rules of etiquette, so perhaps Tip will make a good living as a billiard marker, in the case of Tip though, I doubt it. And now we know how to be billiard markers should we ever want to give it a try. We are told of Tip that "he had troubled himself so little as to the means of his release, that Clennam scarcely needed to have been at the pains of impressing the mind of Mr Plornish on that subject." He does respect and admire his sister Amy, but not enough to change any of his behavior even knowing how it worries her. We're told:

"The same rank Marshalsea flavour was to be recognised in his distinctly perceiving that she sacrificed her life to her father, and in his having no idea that she had done anything for himself."

So much for billiard marking, now we are all able to go and be one if we so desire. One morning Little Dorrit goes on a visit to her sister. She finds that both Fanny and her uncle have already gone to the theater where they are both working, something unknown to William, how to do it anyway. Little Dorrit follows them to the theater and once there is directed to her sister by some men standing at the door:

"On her applying to them, reassured by this resemblance, for a direction to Miss Dorrit, they made way for her to enter a dark hall—it was more like a great grim lamp gone out than anything else—where she could hear the distant playing of music and the sound of dancing feet. A man so much in want of airing that he had a blue mould upon him, sat watching this dark place from a hole in a corner, like a spider; and he told her that he would send a message up to Miss Dorrit by the first lady or gentleman who went through. The first lady who went through had a roll of music, half in her muff and half out of it, and was in such a tumbled condition altogether, that it seemed as if it would be an act of kindness to iron her. But as she was very good-natured, and said, 'Come with me; I'll soon find Miss Dorrit for you,' Miss Dorrit's sister went with her, drawing nearer and nearer at every step she took in the darkness to the sound of music and the sound of dancing feet.

At last they came into a maze of dust, where a quantity of people were tumbling over one another, and where there was such a confusion of unaccountable shapes of beams, bulkheads, brick walls, ropes, and rollers, and such a mixing of gaslight and daylight, that they seemed to have got on the wrong side of the pattern of the universe."

Fanny is astonished to see Amy there asking her how she had found her way there and saying it was so strange seeing her here among the professionals. She goes on to say that little quiet things like Amy can find there way any place and that she would have never been able to do it even though she knew so much more of the world. The narrator tells us:

"It was the family custom to lay it down as family law, that she was a plain domestic little creature, without the great and sage experience of the rest. This family fiction was the family assertion of itself against her services. Not to make too much of them."

Amy tells her sister she has come because she wants to know more about the lady who gave Fanny a bracelet, she has not been quite easy since Fanny told her. They are interrupted as Fanny is called to a dance rehearsal but finally the girls involved in the dance return and begin to get ready to go home. As Fanny and Amy leave they must call to their uncle who is waiting for them in an obscure corner. We're told that even though he is waiting for his niece she still must call for him three or four times before he knows they are there. I want to know more about their uncle, how he got the way he is. I wonder if he was like Amy when he was young. They leave their uncle at a restaurant for his dinner and Fanny then takes her sister to meet Mrs. Merdle, the woman who gave her the bracelet. The woman lives at Harley Street, Cavendish Square in the grandest house on the street. When Fanny knocks on the door it is opened by a footman with powder on his head, backed up by two more footmen with powder on their heads. This gets us to bird reference for Peter:

"Fanny walked in, taking her sister with her; and they went up-stairs with powder going before and powder stopping behind, and were left in a spacious semicircular drawing-room, one of several drawing-rooms, where there was a parrot on the outside of a golden cage holding on by its beak, with its scaly legs in the air, and putting itself into many strange upside-down postures. This peculiarity has been observed in birds of quite another feather, climbing upon golden wires."

I think having a pet bird would drive me insane. Little Dorrit finds them in a room much more splendid than she ever imagined before. Mrs. Merdle enters the room and is described this way:

"The lady was not young and fresh from the hand of Nature, but was young and fresh from the hand of her maid. She had large unfeeling handsome eyes, and dark unfeeling handsome hair, and a broad unfeeling handsome bosom, and was made the most of in every particular. Either because she had a cold, or because it suited her face, she wore a rich white fillet tied over her head and under her chin. And if ever there were an unfeeling handsome chin that looked as if, for certain, it had never been, in familiar parlance, 'chucked' by the hand of man, it was the chin curbed up so tight and close by that laced bridle."

Fanny tells Mrs. Merdle that Amy is curious about her, so she decided to bring her and asks Mrs. Merdle to tell Amy how they happened to know each other. Mrs. Merdle agrees and explains that her husband is very wealthy and his influence is very great and she also has a twenty-three year old son. Her son is a gay little thing, very impressionable and had a fascination with the stage. Because of this he became fascinated by Fanny and even wanted to marry her. This distressed his mother, who went to Fanny to try to end the relationship but found that Fanny had already refused to marry him. Fanny had told Mrs. Merdle that her family's standings in the society in which her father moves is superior to the Merdle's and is acknowledged by everyone. She doesn't bother to tell her where this society her father moves in is or why it is superior. I wish she'd tell me. Mrs. Merdle who is still very concerned about their society’s prejudices had then made it clear to Fanny that any marriage between Fanny and the Merdle's son would cause them to have nothing to do with their son and would leave him a beggar. She had then given Fanny the bracelet as a mark of her appreciation. She also puts something into Fanny's hand as they leave.

As they leave Fanny asks Amy what she thinks and Amy says she is very sorry Fanny took any gifts from Mrs. Merdle. Fanny scorns Amy’s lack of self respect saying she would let herself and her family be trodden on. Mrs. Merdle looks down on them and the least they can do is to make her pay for it. Fanny then goes on to tell Amy that if she despises her sister for being a dancer than why did she make her one? It is Amy's fault she is a dancer in the first place and looked down upon by Mrs. Merdle and people like her. I suppose she does have a point there. Fanny tells her that while she has been shut up, Fanny has been out in society and has become proud and spirited and that while Amy has been thinking of dinner and clothing she has been thinking of the family's honor. Here is our ending:

'Especially as we know,' said Fanny, 'that there certainly is a tone in the place to which you have been so true, which does belong to it, and which does make it different from other aspects of Society. So kiss me once again, Amy dear, and we will agree that we may both be right, and that you are a tranquil, domestic, home-loving, good girl.'

The clarionet had been lamenting most pathetically during this dialogue, but was cut short now by Fanny's announcement that it was time to go; which she conveyed to her uncle by shutting up his scrap of music, and taking the clarionet out of his mouth.

Little Dorrit parted from them at the door, and hastened back to the Marshalsea. It fell dark there sooner than elsewhere, and going into it that evening was like going into a deep trench. The shadow of the wall was on every object. Not least upon the figure in the old grey gown and the black velvet cap, as it turned towards her when she opened the door of the dim room.

'Why not upon me too!' thought Little Dorrit, with the door yet in her hand. 'It was not unreasonable in Fanny.'

The next chapter is titled "Mr. Merdle's Complaint" and here in the twenty first chapter we are still finding new characters. We begin the chapter at the "Merdle establishment", one of a row of homes on both sides of the street that were "very grim with one another", I wonder why. This is what we are told of Mr. Merdle:

"Mr Merdle was immensely rich; a man of prodigious enterprise; a Midas without the ears, who turned all he touched to gold. He was in everything good, from banking to building. He was in Parliament, of course. He was in the City, necessarily. He was Chairman of this, Trustee of that, President of the other. The weightiest of men had said to projectors, 'Now, what name have you got? Have you got Merdle?' And, the reply being in the negative, had said, 'Then I won't look at you.'

This great and fortunate man had provided that extensive bosom which required so much room to be unfeeling enough in, with a nest of crimson and gold some fifteen years before. It was not a bosom to repose upon, but it was a capital bosom to hang jewels upon. Mr Merdle wanted something to hang jewels upon, and he bought it for the purpose. Storr and Mortimer might have married on the same speculation.

Like all his other speculations, it was sound and successful. The jewels showed to the richest advantage. The bosom moving in Society with the jewels displayed upon it, attracted general admiration. Society approving, Mr Merdle was satisfied. He was the most disinterested of men,—did everything for Society, and got as little for himself out of all his gain and care, as a man might.

That is to say, it may be supposed that he got all he wanted, otherwise with unlimited wealth he would have got it. But his desire was to the utmost to satisfy Society (whatever that was), and take up all its drafts upon him for tribute. He did not shine in company; he had not very much to say for himself; he was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, that particular kind of dull red colour in his cheeks which is rather stale than fresh, and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and had reasons for being anxious to hide his hands. In the little he said, he was a pleasant man enough; plain, emphatic about public and private confidence, and tenacious of the utmost deference being shown by every one, in all things, to Society. In this same Society (if that were it which came to his dinners, and to Mrs Merdle's receptions and concerts), he hardly seemed to enjoy himself much, and was mostly to be found against walls and behind doors. Also when he went out to it, instead of its coming home to him, he seemed a little fatigued, and upon the whole rather more disposed for bed; but he was always cultivating it nevertheless, and always moving in it—and always laying out money on it with the greatest liberality."

Mrs. Merdle we already met in the last chapter, one thing I was just thinking about her is that I wouldn't blame her at all for trying to keep her son from marrying a woman who didn't love her son and in fact thought he was an idiot, so if she knew Fanny felt that way and was marrying him for his money and society position (I'm guessing) I wouldn't blame her at all, but she never even met Fanny before she went to her to break off the engagement so it seems that it is Fanny's being a dancer she objected to. So she would have done her best to stop the wedding between her son and a dancer even if the woman loved him deeply. We also find that Mrs. Merdle's son is from her first marriage and he is described as "a chuckle-headed, high-shouldered make, with a general appearance of being, not so much a young man as a swelled boy." We're told that some say his brain was frozen in "in a mighty frost which prevailed at St John's, New Brunswick, at the period of his birth there, and had never thawed from that hour" and another story about him says that he fell out of a window as a child and that his head had been heard to crack. Whatever the stories were Mr. Merdle didn't mind at all he wanted a son for society and Mr. Sparkler (the son's name) did very well in society.

"A son-in-law with these limited talents, might have been a clog upon another man; but Mr Merdle did not want a son-in-law for himself; he wanted a son-in-law for Society. Mr Sparkler having been in the Guards, and being in the habit of frequenting all the races, and all the lounges, and all the parties, and being well known, Society was satisfied with its son-in-law. This happy result Mr Merdle would have considered well attained, though Mr Sparkler had been a more expensive article. And he did not get Mr Sparkler by any means cheap for Society, even as it was."

I am assuming that son-in-law was used in Dicken's day the same way step-son is used now. Around here anyway. That night - the night after Fanny and Amy visit Mrs. Merdle I suppose they mean, the Merdle's have a dinner party, as for the guests they are:

"magnates from the Court and magnates from the City, magnates from the Commons and magnates from the Lords, magnates from the bench and magnates from the bar, Bishop magnates, Treasury magnates, Horse Guard magnates, Admiralty magnates,—all the magnates that keep us going, and sometimes trip us up".

These guests, who Dickens gives names like Treasury, Bar, Horse Guards, and Bishop, are discussing how Mr. Merdle has had another successful deal that has earned him lots of money. Mr. Merdle shows up late as usual, he is the last to arrive. Treasury congratulates Mr. Merdle on a new achievement, Bar comes up and mentions that Merdle is one of the greatest converters of the root of all evil into the root of all good, or some such thing, and so on and on it goes.

A physician at the party - "a famous physician, who knew everybody, and whom everybody knew" inquires after Mr. Merdle’s health, and Merdle says that he is no better. The physician tells him to come see him next day. Bar and Bishop overhear and when Mr. Merdle walks away ask after Merdle's health. The physician tells them that Mr. Merdle is as healthy as a rhinoceros, has the digestion of an ostrich, and the concentration of an oyster - I suppose these are all good things although I'm not sure how an oyster concentrates. The doctor goes on to say that Merdle may have a deep-seated recondite complaint that he hasn't found yet - remember that for later - and that has finally brought us both to the name and the end of the chapter:

"Mr Merdle's complaint. Society and he had so much to do with one another in all things else, that it is hard to imagine his complaint, if he had one, being solely his own affair. Had he that deep-seated recondite complaint, and did any doctor find it out? Patience, in the meantime, the shadow of the Marshalsea wall was a real darkening influence, and could be seen on the Dorrit Family at any stage of the sun's course."

"Mr Merdle was immensely rich; a man of prodigious enterprise; a Midas without the ears, who turned all he touched to gold. He was in everything good, from banking to building. He was in Parliament, of course. He was in the City, necessarily. He was Chairman of this, Trustee of that, President of the other. The weightiest of men had said to projectors, 'Now, what name have you got? Have you got Merdle?' And, the reply being in the negative, had said, 'Then I won't look at you.'

This great and fortunate man had provided that extensive bosom which required so much room to be unfeeling enough in, with a nest of crimson and gold some fifteen years before. It was not a bosom to repose upon, but it was a capital bosom to hang jewels upon. Mr Merdle wanted something to hang jewels upon, and he bought it for the purpose. Storr and Mortimer might have married on the same speculation.

Like all his other speculations, it was sound and successful. The jewels showed to the richest advantage. The bosom moving in Society with the jewels displayed upon it, attracted general admiration. Society approving, Mr Merdle was satisfied. He was the most disinterested of men,—did everything for Society, and got as little for himself out of all his gain and care, as a man might.

That is to say, it may be supposed that he got all he wanted, otherwise with unlimited wealth he would have got it. But his desire was to the utmost to satisfy Society (whatever that was), and take up all its drafts upon him for tribute. He did not shine in company; he had not very much to say for himself; he was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, that particular kind of dull red colour in his cheeks which is rather stale than fresh, and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and had reasons for being anxious to hide his hands. In the little he said, he was a pleasant man enough; plain, emphatic about public and private confidence, and tenacious of the utmost deference being shown by every one, in all things, to Society. In this same Society (if that were it which came to his dinners, and to Mrs Merdle's receptions and concerts), he hardly seemed to enjoy himself much, and was mostly to be found against walls and behind doors. Also when he went out to it, instead of its coming home to him, he seemed a little fatigued, and upon the whole rather more disposed for bed; but he was always cultivating it nevertheless, and always moving in it—and always laying out money on it with the greatest liberality."

Mrs. Merdle we already met in the last chapter, one thing I was just thinking about her is that I wouldn't blame her at all for trying to keep her son from marrying a woman who didn't love her son and in fact thought he was an idiot, so if she knew Fanny felt that way and was marrying him for his money and society position (I'm guessing) I wouldn't blame her at all, but she never even met Fanny before she went to her to break off the engagement so it seems that it is Fanny's being a dancer she objected to. So she would have done her best to stop the wedding between her son and a dancer even if the woman loved him deeply. We also find that Mrs. Merdle's son is from her first marriage and he is described as "a chuckle-headed, high-shouldered make, with a general appearance of being, not so much a young man as a swelled boy." We're told that some say his brain was frozen in "in a mighty frost which prevailed at St John's, New Brunswick, at the period of his birth there, and had never thawed from that hour" and another story about him says that he fell out of a window as a child and that his head had been heard to crack. Whatever the stories were Mr. Merdle didn't mind at all he wanted a son for society and Mr. Sparkler (the son's name) did very well in society.

"A son-in-law with these limited talents, might have been a clog upon another man; but Mr Merdle did not want a son-in-law for himself; he wanted a son-in-law for Society. Mr Sparkler having been in the Guards, and being in the habit of frequenting all the races, and all the lounges, and all the parties, and being well known, Society was satisfied with its son-in-law. This happy result Mr Merdle would have considered well attained, though Mr Sparkler had been a more expensive article. And he did not get Mr Sparkler by any means cheap for Society, even as it was."

I am assuming that son-in-law was used in Dicken's day the same way step-son is used now. Around here anyway. That night - the night after Fanny and Amy visit Mrs. Merdle I suppose they mean, the Merdle's have a dinner party, as for the guests they are:

"magnates from the Court and magnates from the City, magnates from the Commons and magnates from the Lords, magnates from the bench and magnates from the bar, Bishop magnates, Treasury magnates, Horse Guard magnates, Admiralty magnates,—all the magnates that keep us going, and sometimes trip us up".

These guests, who Dickens gives names like Treasury, Bar, Horse Guards, and Bishop, are discussing how Mr. Merdle has had another successful deal that has earned him lots of money. Mr. Merdle shows up late as usual, he is the last to arrive. Treasury congratulates Mr. Merdle on a new achievement, Bar comes up and mentions that Merdle is one of the greatest converters of the root of all evil into the root of all good, or some such thing, and so on and on it goes.

A physician at the party - "a famous physician, who knew everybody, and whom everybody knew" inquires after Mr. Merdle’s health, and Merdle says that he is no better. The physician tells him to come see him next day. Bar and Bishop overhear and when Mr. Merdle walks away ask after Merdle's health. The physician tells them that Mr. Merdle is as healthy as a rhinoceros, has the digestion of an ostrich, and the concentration of an oyster - I suppose these are all good things although I'm not sure how an oyster concentrates. The doctor goes on to say that Merdle may have a deep-seated recondite complaint that he hasn't found yet - remember that for later - and that has finally brought us both to the name and the end of the chapter:

"Mr Merdle's complaint. Society and he had so much to do with one another in all things else, that it is hard to imagine his complaint, if he had one, being solely his own affair. Had he that deep-seated recondite complaint, and did any doctor find it out? Patience, in the meantime, the shadow of the Marshalsea wall was a real darkening influence, and could be seen on the Dorrit Family at any stage of the sun's course."

And finally in Chapter 22 titled "A Puzzle" we find that our Father of the Marshalea doesn't care for Arthur Clennam at all mainly because Arthur doesn't leave him those "testimonials" every one else does, I like this Amy's father less and less all the time:

"Mr Clennam did not increase in favour with the Father of the Marshalsea in the ratio of his increasing visits. His obtuseness on the great Testimonial question was not calculated to awaken admiration in the paternal breast, but had rather a tendency to give offence in that sensitive quarter, and to be regarded as a positive shortcoming in point of gentlemanly feeling. An impression of disappointment, occasioned by the discovery that Mr Clennam scarcely possessed that delicacy for which, in the confidence of his nature, he had been inclined to give him credit, began to darken the fatherly mind in connection with that gentleman. The father went so far as to say, in his private family circle, that he feared Mr Clennam was not a man of high instincts. He was happy, he observed, in his public capacity as leader and representative of the College, to receive Mr Clennam when he called to pay his respects; but he didn't find that he got on with him personally. There appeared to be something (he didn't know what it was) wanting in him. Howbeit, the father did not fail in any outward show of politeness, but, on the contrary, honoured him with much attention; perhaps cherishing the hope that, although not a man of a sufficiently brilliant and spontaneous turn of mind to repeat his former testimonial unsolicited, it might still be within the compass of his nature to bear the part of a responsive gentleman, in any correspondence that way tending."

I'm not exactly sure why Arthur keeps visiting in the first place, he must be able to tell that Mr. Dorrit doesn't like him and wants him to leave him money when he leaves, he also must know that this hurts Amy every time it happens, and if his reason is to visit Amy why doesn't he do that at his mother's home or her uncle's? Mr. Chivery approaches Mr. Clennam one day as he leaves from one of these visits and asks if he could drop into his wife’s tobacco shop. She wishes to discuss Amy Dorrit with him and Arthur immediately agrees. When he arrives, Mrs. Chivery takes him to the parlor with a little window looking out at a dull little back yard and shows him a very despondent John. She tells Arthur that her son is pining away for Amy Dorrit and sits out in the yard for hours. She blames the family, certain that Amy herself loves her son telling Arthur that the brother and sister are against him, their views are "too high". Also Amy's father wants her all to himself and is against sharing her with anyone.

Arthur is bothered when he hears this, he finds it disappointing and disagreeable to think of her in love with young Mr Chivery. However, he promises to do anything that will add to the happiness of Amy Dorrit. He tells Mrs. Chivery that first he wants to make sure that Amy does love John Chivery and asks her to ask her son and make sure that this is indeed how Amy feels. Mrs. Chivery doesn’t think there is any doubt about this, but still they part good friends.

When Arthur leaves he takes the Iron Bridge it being much quieter than the London Bridge and sees Amy walking on the bridge. She waits for him and as they walk they talk about her worry about her father and Arthur tells her what a comfort she is to him. As they walk Maggy arrives. Little Dorrit asks why Maggy isn't with her father and Maggy informs her that she was, but that both Mr. Dorrit and Tip have sent her on an errand to the same address to deliver letters they had written. As it turns out, the letters are for Arthur Clennam although Amy was never to know of them. Both of them are asking for money although why a man who has been in prison for debt for 22 years would suddenly ask someone for money is beyond me, as for Tip, I believe he'd ask money from anyone although I'm not sure what brought Arthur to his mind, I wouldn't think they would see each other very often. Arthur agrees to Mr. Dorrit's request but refuses Tip. Good for him. And the chapter ends with this, could it give us a clue to what may be coming?:

"When he rejoined Little Dorrit, and they had begun walking as before, she said all at once:

'I think I had better go. I had better go home.'

'Don't be distressed,' said Clennam, 'I have answered the letters. They were nothing. You know what they were. They were nothing.'

'But I am afraid,' she returned, 'to leave him, I am afraid to leave any of them. When I am gone, they pervert—but they don't mean it—even Maggy.'

'It was a very innocent commission that she undertook, poor thing. And in keeping it secret from you, she supposed, no doubt, that she was only saving you uneasiness.'

'Yes, I hope so, I hope so. But I had better go home! It was but the other day that my sister told me I had become so used to the prison that I had its tone and character. It must be so. I am sure it must be when I see these things. My place is there. I am better there, it is unfeeling in me to be here, when I can do the least thing there. Good-bye. I had far better stay at home!'

The agonized way in which she poured this out, as if it burst of itself from her suppressed heart, made it difficult for Clennam to keep the tears from his eyes as he saw and heard her.

'Don't call it home, my child!' he entreated. 'It is always painful to me to hear you call it home.'

'But it is home! What else can I call home? Why should I ever forget it for a single moment?'

'You never do, dear Little Dorrit, in any good and true service.'

'I hope not, O I hope not! But it is better for me to stay there; much better, much more dutiful, much happier. Please don't go with me, let me go by myself. Good-bye, God bless you. Thank you, thank you.'

He felt that it was better to respect her entreaty, and did not move while her slight form went quickly away from him. When it had fluttered out of sight, he turned his face towards the water and stood thinking.

She would have been distressed at any time by this discovery of the letters; but so much so, and in that unrestrainable way?

No.

When she had seen her father begging with his threadbare disguise on, when she had entreated him not to give her father money, she had been distressed, but not like this. Something had made her keenly and additionally sensitive just now. Now, was there some one in the hopeless unattainable distance? Or had the suspicion been brought into his mind, by his own associations of the troubled river running beneath the bridge with the same river higher up, its changeless tune upon the prow of the ferry-boat, so many miles an hour the peaceful flowing of the stream, here the rushes, there the lilies, nothing uncertain or unquiet?

He thought of his poor child, Little Dorrit, for a long time there; he thought of her going home; he thought of her in the night; he thought of her when the day came round again. And the poor child Little Dorrit thought of him—too faithfully, ah, too faithfully!—in the shadow of the Marshalsea wall."

And with that I hand the book back to Tristram for the next installment. Hopefully my next turn won't be filled with so many Dorrits.

"Mr Clennam did not increase in favour with the Father of the Marshalsea in the ratio of his increasing visits. His obtuseness on the great Testimonial question was not calculated to awaken admiration in the paternal breast, but had rather a tendency to give offence in that sensitive quarter, and to be regarded as a positive shortcoming in point of gentlemanly feeling. An impression of disappointment, occasioned by the discovery that Mr Clennam scarcely possessed that delicacy for which, in the confidence of his nature, he had been inclined to give him credit, began to darken the fatherly mind in connection with that gentleman. The father went so far as to say, in his private family circle, that he feared Mr Clennam was not a man of high instincts. He was happy, he observed, in his public capacity as leader and representative of the College, to receive Mr Clennam when he called to pay his respects; but he didn't find that he got on with him personally. There appeared to be something (he didn't know what it was) wanting in him. Howbeit, the father did not fail in any outward show of politeness, but, on the contrary, honoured him with much attention; perhaps cherishing the hope that, although not a man of a sufficiently brilliant and spontaneous turn of mind to repeat his former testimonial unsolicited, it might still be within the compass of his nature to bear the part of a responsive gentleman, in any correspondence that way tending."

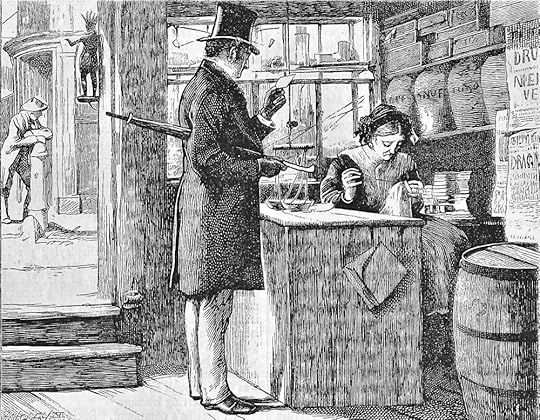

I'm not exactly sure why Arthur keeps visiting in the first place, he must be able to tell that Mr. Dorrit doesn't like him and wants him to leave him money when he leaves, he also must know that this hurts Amy every time it happens, and if his reason is to visit Amy why doesn't he do that at his mother's home or her uncle's? Mr. Chivery approaches Mr. Clennam one day as he leaves from one of these visits and asks if he could drop into his wife’s tobacco shop. She wishes to discuss Amy Dorrit with him and Arthur immediately agrees. When he arrives, Mrs. Chivery takes him to the parlor with a little window looking out at a dull little back yard and shows him a very despondent John. She tells Arthur that her son is pining away for Amy Dorrit and sits out in the yard for hours. She blames the family, certain that Amy herself loves her son telling Arthur that the brother and sister are against him, their views are "too high". Also Amy's father wants her all to himself and is against sharing her with anyone.

Arthur is bothered when he hears this, he finds it disappointing and disagreeable to think of her in love with young Mr Chivery. However, he promises to do anything that will add to the happiness of Amy Dorrit. He tells Mrs. Chivery that first he wants to make sure that Amy does love John Chivery and asks her to ask her son and make sure that this is indeed how Amy feels. Mrs. Chivery doesn’t think there is any doubt about this, but still they part good friends.

When Arthur leaves he takes the Iron Bridge it being much quieter than the London Bridge and sees Amy walking on the bridge. She waits for him and as they walk they talk about her worry about her father and Arthur tells her what a comfort she is to him. As they walk Maggy arrives. Little Dorrit asks why Maggy isn't with her father and Maggy informs her that she was, but that both Mr. Dorrit and Tip have sent her on an errand to the same address to deliver letters they had written. As it turns out, the letters are for Arthur Clennam although Amy was never to know of them. Both of them are asking for money although why a man who has been in prison for debt for 22 years would suddenly ask someone for money is beyond me, as for Tip, I believe he'd ask money from anyone although I'm not sure what brought Arthur to his mind, I wouldn't think they would see each other very often. Arthur agrees to Mr. Dorrit's request but refuses Tip. Good for him. And the chapter ends with this, could it give us a clue to what may be coming?:

"When he rejoined Little Dorrit, and they had begun walking as before, she said all at once:

'I think I had better go. I had better go home.'

'Don't be distressed,' said Clennam, 'I have answered the letters. They were nothing. You know what they were. They were nothing.'

'But I am afraid,' she returned, 'to leave him, I am afraid to leave any of them. When I am gone, they pervert—but they don't mean it—even Maggy.'

'It was a very innocent commission that she undertook, poor thing. And in keeping it secret from you, she supposed, no doubt, that she was only saving you uneasiness.'

'Yes, I hope so, I hope so. But I had better go home! It was but the other day that my sister told me I had become so used to the prison that I had its tone and character. It must be so. I am sure it must be when I see these things. My place is there. I am better there, it is unfeeling in me to be here, when I can do the least thing there. Good-bye. I had far better stay at home!'

The agonized way in which she poured this out, as if it burst of itself from her suppressed heart, made it difficult for Clennam to keep the tears from his eyes as he saw and heard her.

'Don't call it home, my child!' he entreated. 'It is always painful to me to hear you call it home.'

'But it is home! What else can I call home? Why should I ever forget it for a single moment?'

'You never do, dear Little Dorrit, in any good and true service.'

'I hope not, O I hope not! But it is better for me to stay there; much better, much more dutiful, much happier. Please don't go with me, let me go by myself. Good-bye, God bless you. Thank you, thank you.'

He felt that it was better to respect her entreaty, and did not move while her slight form went quickly away from him. When it had fluttered out of sight, he turned his face towards the water and stood thinking.

She would have been distressed at any time by this discovery of the letters; but so much so, and in that unrestrainable way?

No.

When she had seen her father begging with his threadbare disguise on, when she had entreated him not to give her father money, she had been distressed, but not like this. Something had made her keenly and additionally sensitive just now. Now, was there some one in the hopeless unattainable distance? Or had the suspicion been brought into his mind, by his own associations of the troubled river running beneath the bridge with the same river higher up, its changeless tune upon the prow of the ferry-boat, so many miles an hour the peaceful flowing of the stream, here the rushes, there the lilies, nothing uncertain or unquiet?

He thought of his poor child, Little Dorrit, for a long time there; he thought of her going home; he thought of her in the night; he thought of her when the day came round again. And the poor child Little Dorrit thought of him—too faithfully, ah, too faithfully!—in the shadow of the Marshalsea wall."

And with that I hand the book back to Tristram for the next installment. Hopefully my next turn won't be filled with so many Dorrits.

Kim wrote: "The next chapter is titled "Mr. Merdle's Complaint" and here in the twenty first chapter we are still finding new characters. We begin the chapter at the "Merdle establishment", one of a row of hom..."

Kim wrote: "The next chapter is titled "Mr. Merdle's Complaint" and here in the twenty first chapter we are still finding new characters. We begin the chapter at the "Merdle establishment", one of a row of hom..."I think my favorite part of this chapter is how Mrs. Merdle is reduced to "the bosom," and we get to hear all about the bosom's past and its social activities.

I was a bit surprised to have a whole new family introduced in this installment though (the Merdles). There seems to be no end to this book's expansion!

Kim wrote: "Chapter 20 is titled "Moving in Society" and we find Tip still out of debtors prison - barely I'm guessing - and working as a billiard marker. Now since this didn't sound like much of a job to me, ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 20 is titled "Moving in Society" and we find Tip still out of debtors prison - barely I'm guessing - and working as a billiard marker. Now since this didn't sound like much of a job to me, ..."Thank you for the billiard research, Kim! I read it twice in case I was missing any particular way that Tip could get himself into trouble (helping someone cheat at billiards, for instance?)--and nothing jumped out at me, but I'm sure he will be resourceful.

Fanny's workplace seems so grim that I am wondering if it's veered into prostitution yet, but so far I don't see her looking all remorseful and tragic and referring to horrifying things she can't name, so I guess she's just at the low-budget end of the entertainment industry.

Curious what people make of the distinction between Fanny being a "professional" and Amy not, even though they both work for a living.

I am very grateful for you, Kim, for having found that wonderfully-written explanation of what a billiard marker was because in my edition they have notes on most things but they apparently assumed that everyone knew what a billiard marker is, which I didn't. And that even though I sometimes watch snooker matches on TV where the billiard marker is in full action. Nowadays, he or she always tells people to switch of their mobiles or to keep quiet. A nice job, actually, but I don't know if I'd really have liked to have Tip as my billiard marker.

This week, I was most struck by Arthur Clennam's strange reaction to Mrs. Chivery's revelation: Is he jealous of young John, or does it not suit his image of Amy on a pedestal that there might be someone who is in love with her and whom she might even be in love with? And why is that so? Be that as it may, Arthur is definitely disenchanted to a certain extent, and I find this very dismaying: Does this not show that Arthur's interest in Amy is anything but entirely selfless? That, on the contrary, he, in exchange for his help, expects a certain angel-like purity from her, which cannot be made compatible with her having the same interests as most women her age? Does Amy have to be an asexual being to suit his picture of her? This is utterly bewildering to me, and to make matters even more so, Amy's rather snobbish treatment of young John seems to imply that the author (or narrator) himself is applying the same standard to Amy. How eerie!

This week, I was most struck by Arthur Clennam's strange reaction to Mrs. Chivery's revelation: Is he jealous of young John, or does it not suit his image of Amy on a pedestal that there might be someone who is in love with her and whom she might even be in love with? And why is that so? Be that as it may, Arthur is definitely disenchanted to a certain extent, and I find this very dismaying: Does this not show that Arthur's interest in Amy is anything but entirely selfless? That, on the contrary, he, in exchange for his help, expects a certain angel-like purity from her, which cannot be made compatible with her having the same interests as most women her age? Does Amy have to be an asexual being to suit his picture of her? This is utterly bewildering to me, and to make matters even more so, Amy's rather snobbish treatment of young John seems to imply that the author (or narrator) himself is applying the same standard to Amy. How eerie!

What we learn about Tip and Fanny in this week's chapters does not exactly redound to the siblings' honour: Tip does not even care to know to whom he is indebted for his release from the prison, but he takes it as a matter of course, as something he may even regard himself entitled to - because of what exactly?

As to Fanny, her shady bargain with Mrs. Merdle is amounting to blackmail, or even to some kind of passive prostitution, isn't it? And then there is her crazy reasoning of extorting the money and the bracelet for the family honour. What I really cannot get my head around is how Amy can see all this and not speak out about it. I've never had a lot of sympathy for her, but even that little amount is dwindling away.

I really loved how the narrator kept pointing out that Mrs. Merdle needed her large bosom to have enough room to be unfeeling in. What do you think about her husband?

As to Fanny, her shady bargain with Mrs. Merdle is amounting to blackmail, or even to some kind of passive prostitution, isn't it? And then there is her crazy reasoning of extorting the money and the bracelet for the family honour. What I really cannot get my head around is how Amy can see all this and not speak out about it. I've never had a lot of sympathy for her, but even that little amount is dwindling away.

I really loved how the narrator kept pointing out that Mrs. Merdle needed her large bosom to have enough room to be unfeeling in. What do you think about her husband?

Julie wrote: " my favorite part of this chapter is how Mrs. Merdle is reduced to "the bosom," and we get to hear all about the bosom's past and its social activities...."

Julie wrote: " my favorite part of this chapter is how Mrs. Merdle is reduced to "the bosom," and we get to hear all about the bosom's past and its social activities...."I usually don't care for these dinner party scenes in which Dickens introduces us to representatives of whatever institution he's railing against - the Boodles, et al, in Bleak House, the magnates here in Dorrit, etc. - but either I'm getting used to them, or this chapter was more entertaining than similar ones in other books. I really enjoyed reading about Treasury, Bar, etc. - and, yes, "the bosom". Can't we all just picture Mrs. Merdle, with her brooches and necklaces drawing attention to her decolletage (or vice versa)?

Mrs. Merdle's interactions with Fanny were quite delicious, and I love how Dickens managed to make them both feel as if they were somehow superior to the other. As for Amy's reaction - again, I can't quite figure her out. She's got pride, but it's misplaced. And she's obviously intimidated by her older siblings, still, perhaps, thinking they have some knowledge and wisdom that she hasn't yet gained.

I always have the same confusion as Kim mentioned when Dickens refers to an in-law, where we would say, "step child". Throws me off every time. I wonder if it's still the same in the UK, or if they have changed the meaning over the years. At any rate, Sparkler is bound to provide some diversions for us as we go forward. Interesting name.

Is the bird also just an amusing way to give some depth to the scenes at the Merdle home, or do you think he is symbolic of something?

Isn't it interesting how much Arthur has insinuated himself into the Dorrits' lives? So much so that Mrs. Chivery, whom we (and presumably Arthur) had never met before, summons him to her home/shop to request his assistance in convincing Amy to accept John. What the... ?? In previous readings of the book, I was just trying to follow the plot, and went with it. This time, though, it occurs to me how bizarre that is. The whole relationship seems weird and kind of creepy to me. What's our timeline here? How long has it been since Arthur got off the boat? Seems like 3-4 weeks to me, but maybe it's been longer? Why on Earth is he so wrapped up in this family? The only thing I can come up with is that he's got an attraction to Amy that he's not yet willing to recognize or admit. Can you think of any other reason? And, if this theory is valid, are his attentions romantic or somewhat controlling and stalker-like? If Amy had the balls to tell him to go away, would he do it, or would he keep finding excuses to be hanging around? But she won't. It's obvious from the exchange when he helped Tip "anonymously" that she's delighted with his attentions, despite her humility. Is this really any better than Fanny's taking the bracelet from Mrs. Merdle?

Isn't it interesting how much Arthur has insinuated himself into the Dorrits' lives? So much so that Mrs. Chivery, whom we (and presumably Arthur) had never met before, summons him to her home/shop to request his assistance in convincing Amy to accept John. What the... ?? In previous readings of the book, I was just trying to follow the plot, and went with it. This time, though, it occurs to me how bizarre that is. The whole relationship seems weird and kind of creepy to me. What's our timeline here? How long has it been since Arthur got off the boat? Seems like 3-4 weeks to me, but maybe it's been longer? Why on Earth is he so wrapped up in this family? The only thing I can come up with is that he's got an attraction to Amy that he's not yet willing to recognize or admit. Can you think of any other reason? And, if this theory is valid, are his attentions romantic or somewhat controlling and stalker-like? If Amy had the balls to tell him to go away, would he do it, or would he keep finding excuses to be hanging around? But she won't. It's obvious from the exchange when he helped Tip "anonymously" that she's delighted with his attentions, despite her humility. Is this really any better than Fanny's taking the bracelet from Mrs. Merdle? I'm seeing this novel in a whole different light than I have in the past, and it's kind of fascinating. Reading Dickens is like what they say about rivers - you never step in the same one twice.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "The next chapter is titled "Mr. Merdle's Complaint" and here in the twenty first chapter we are still finding new characters. We begin the chapter at the "Merdle establishment", one of ..."

Hi Julie

Yes, it’s great to see how Mrs Merdle is reduced to “the bosom.” Or perhaps we should say she is expanded into “the bosom.” Did it remind you of the prow of an old time sailing ship?

Is it me or is there an over abundance of names that Dickens gives to characters in this book to telegraph their habits, weaknesses or remarkable characteristics? We have a Bosom, a Father of the Marshalsea, Barnacles, a Pet, a Little Mother, a Tattycoram, a Wobbler, a John Baptist, a Sparkler and, could it be the surname Merdle is tied to the French word that means, well, “poop?”

Hi Julie

Yes, it’s great to see how Mrs Merdle is reduced to “the bosom.” Or perhaps we should say she is expanded into “the bosom.” Did it remind you of the prow of an old time sailing ship?

Is it me or is there an over abundance of names that Dickens gives to characters in this book to telegraph their habits, weaknesses or remarkable characteristics? We have a Bosom, a Father of the Marshalsea, Barnacles, a Pet, a Little Mother, a Tattycoram, a Wobbler, a John Baptist, a Sparkler and, could it be the surname Merdle is tied to the French word that means, well, “poop?”

Kim

Thanks for the reference to the bird. Not just any bird, but a big bird with scales on its legs, hanging upside down from a golden cage. Now, the sirens went off in my head. Hmmm … cage, and we have seen many previous forms of imprisonment in the novel so far. A golden cage. Now why would Dickens draw our attention to that fact? Hanging upside down. Why would Dickens draw our attention to that detail? Scales on legs. A rather unpleasant detail. So what’s up with this bird?

Golden cage, upside down. Could it be that this bird and its cage signals a transition between the rather threadbare and shoddy world of the theatre and the entry into an opulent house that is filled with the servants’ powder and the richly adorned bosom of Mrs Merdle.

The contrast of those two establishments is striking. I don’t think Dickens put the contrast of these two places in the same chapter by mistake. Poverty vs apparent riches, separated by the fulcrum of an upside down bird and a golden cage.

What great symbolism and foreshadowing.

Thanks for the reference to the bird. Not just any bird, but a big bird with scales on its legs, hanging upside down from a golden cage. Now, the sirens went off in my head. Hmmm … cage, and we have seen many previous forms of imprisonment in the novel so far. A golden cage. Now why would Dickens draw our attention to that fact? Hanging upside down. Why would Dickens draw our attention to that detail? Scales on legs. A rather unpleasant detail. So what’s up with this bird?

Golden cage, upside down. Could it be that this bird and its cage signals a transition between the rather threadbare and shoddy world of the theatre and the entry into an opulent house that is filled with the servants’ powder and the richly adorned bosom of Mrs Merdle.

The contrast of those two establishments is striking. I don’t think Dickens put the contrast of these two places in the same chapter by mistake. Poverty vs apparent riches, separated by the fulcrum of an upside down bird and a golden cage.

What great symbolism and foreshadowing.

Mary Lou wrote: "Isn't it interesting how much Arthur has insinuated himself into the Dorrits' lives? So much so that Mrs. Chivery, whom we (and presumably Arthur) had never met before, summons him to her home/shop..."

Hi Mary Lou

You are so right. Never the same book. As I read the comments on Amy I am torn as to how to perceive her. I still have more sympathy for what she is enduring. Yes, at her age it is her choice to tragically overindulge her father, enable her siblings and mother Maggy. These flaws in her character are, I believe, balanced out by her maturity. She is a person who shows responsibility, she learns a skill and gets a job, she is calm, insightful (she knows a marriage proposal is coming) and obviously very responsible.

I think by rejecting John’s interest Amy shows an emotional maturity and an awareness of how important mature emotional attachments are, or could be, given the right person. I think when we see Amy with her sister at the Merdle’s she gets a further insight into how courtships and emotions work. I think the Sparkler - Fanny attachment is a step towards Amy’s own emotional awareness.

Unlike our poor Little Nell, I think Dickens let’s us see how Little Dorrit will grow up emotionally, and perhaps even physically.

Hi Mary Lou

You are so right. Never the same book. As I read the comments on Amy I am torn as to how to perceive her. I still have more sympathy for what she is enduring. Yes, at her age it is her choice to tragically overindulge her father, enable her siblings and mother Maggy. These flaws in her character are, I believe, balanced out by her maturity. She is a person who shows responsibility, she learns a skill and gets a job, she is calm, insightful (she knows a marriage proposal is coming) and obviously very responsible.

I think by rejecting John’s interest Amy shows an emotional maturity and an awareness of how important mature emotional attachments are, or could be, given the right person. I think when we see Amy with her sister at the Merdle’s she gets a further insight into how courtships and emotions work. I think the Sparkler - Fanny attachment is a step towards Amy’s own emotional awareness.

Unlike our poor Little Nell, I think Dickens let’s us see how Little Dorrit will grow up emotionally, and perhaps even physically.

Mary Lou wrote: "Isn't it interesting how much Arthur has insinuated himself into the Dorrits' lives? So much so that Mrs. Chivery, whom we (and presumably Arthur) had never met before, summons him to her home/shop..."

I never thought of that before. Is he there so often that people now go to him for advice on the Dorrit's? My word, he must practically live there. Why would he want to?

I never thought of that before. Is he there so often that people now go to him for advice on the Dorrit's? My word, he must practically live there. Why would he want to?

Peter wrote: "Kim

Thanks for the reference to the bird. Not just any bird, but a big bird with scales on its legs, hanging upside down from a golden cage. Now, the sirens went off in my head. Hmmm … cage, and w..."

Now that you pointed that out I'm wondering, do birds ever really hang upside down any where at all?

Thanks for the reference to the bird. Not just any bird, but a big bird with scales on its legs, hanging upside down from a golden cage. Now, the sirens went off in my head. Hmmm … cage, and w..."

Now that you pointed that out I'm wondering, do birds ever really hang upside down any where at all?

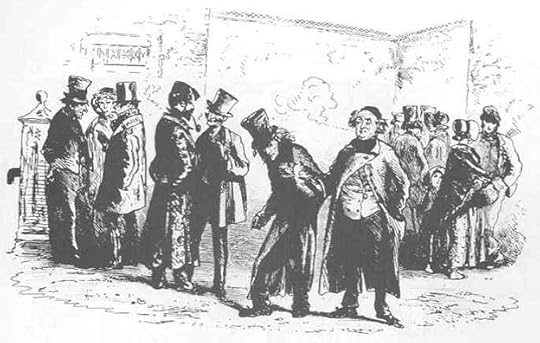

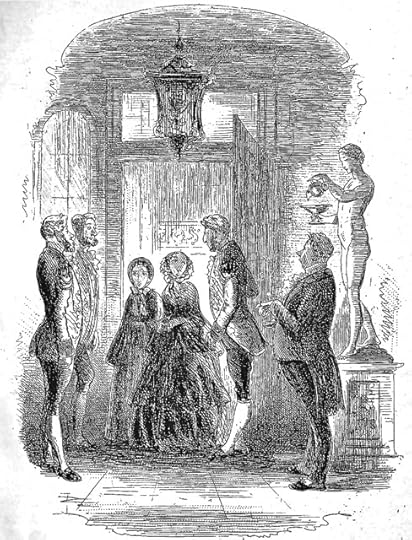

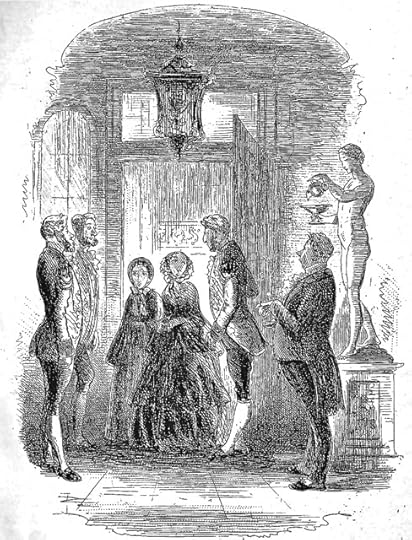

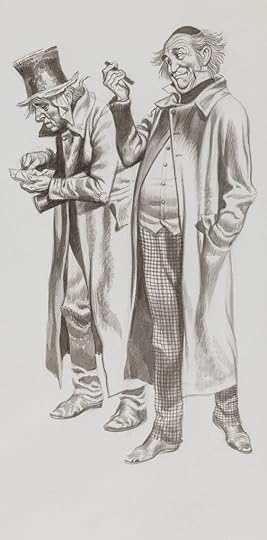

The Brothers

Chapter 19, Book 1

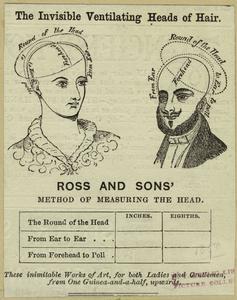

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The brothers William and Frederick Dorrit, walking up and down the College-yard — of course on the aristocratic or Pump side, for the Father made it a point of his state to be chary of going among his children on the Poor side, except on Sunday mornings, Christmas Days, and other occasions of ceremony, in the observance whereof he was very punctual, and at which times he laid his hand upon the heads of their infants, and blessed those young insolvents with a benignity that was highly edifying — the brothers, walking up and down the College-yard together, were a memorable sight. Frederick the free, was so humbled, bowed, withered, and faded; William the bond, was so courtly, condescending, and benevolently conscious of a position; that in this regard only, if in no other, the brothers were a spectacle to wonder at.

They walked up and down the yard on the evening of Little Dorrit's Sunday interview with her lover on the Iron Bridge. The cares of state were over for that day, the Drawing Room had been well attended, several new presentations had taken place, the three-and- sixpence accidentally left on the table had accidentally increased to twelve shillings, and the Father of the Marshalsea refreshed himself with a whiff of cigar. As he walked up and down, affably accommodating his step to the shuffle of his brother, not proud in his superiority, but considerate of that poor creature, bearing with him, and breathing toleration of his infirmities in every little puff of smoke that issued from his lips and aspired to get over the spiked wall, he was a sight to wonder at. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 19.

Commentary:

His more conventional etching techniques allow Browne to do justice to the prison identity of the Dorrit family in at least three illustrations. The technique of parallel and contrast between plates is evident, even in the captions alone, in "The Brothers" (Bk. 1, ch. 19) and "Miss Dorrit and Little Dorrit" (Bk. 1, ch. 20). In the first, a well-fed, supercilious man strolls patronizingly in the Marshalsea yard with "his brother Frederick of the dim eye, palsied hand, bent form, and groping mind," as though it were indeed a "College-yard," the man in the dressing gown and the disreputable characters near the pump were not there, and the woman at the gate with her small child were not taking leave of "a new Collegian" (Bk. 1, ch. 19). This horizontal etching takes full advantage of its available space, the figures in the background being serviceable and no more — though creating no feeling of slackness on the artist's part. The smoke which William is blowing out over his brother's head resembles a speechballoon (a device going back to earlier graphic satire), implying that this puff on a cigar represents an utterance of the condescending, self-assumed superiority of the prisoner brother. — Michael Steig, "Chapter 6: Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness".

As Steig has noted, Phiz makes the brothers flip sides of the same coin: Frederick, the broken-down, shabby musician with ragged hair, is bowed over with care; William, the pater familias, is casually commanding, puffing on a cigar, his erect posture a sharp contrast to his brother's. Further, the artist has positioned the Dorrit brothers between two very different groups: to the left, men and a woman apparently without families are conversing confidentially, the man in dressing-gown and fez smoking a pipe, his hands behind his back, relaxed, sophisticated, and even (apparently) affluent, or at least well-provided for under such circumstances. To the right, however, are six somewhat younger adults (two women and three men) and a child in a bonnet. William, then, participates in the characteristics of both groups: although the head of an extended family and attended by a daughter, he strikes a sophisticated pose, smoking and striking a casually sophisticated pose, like the inmate in the floral dressing-gown who is (apparently) not weighed down by family responsibilities. The dividing line between the "fashionable" and plebeian sides of the yard, the center of the community, the pump, is immediately to the left, so that the viewer must assume that all fourteen characters in the vignetted illustration are sophisticates rather than misfits - at least, in their own minds.

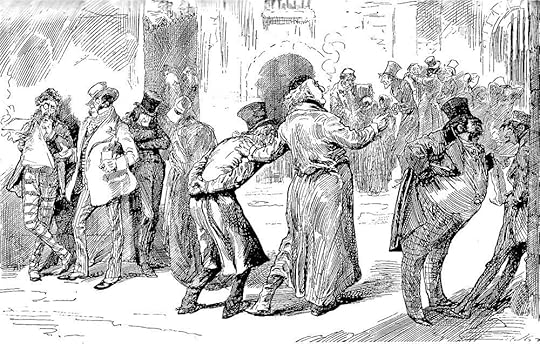

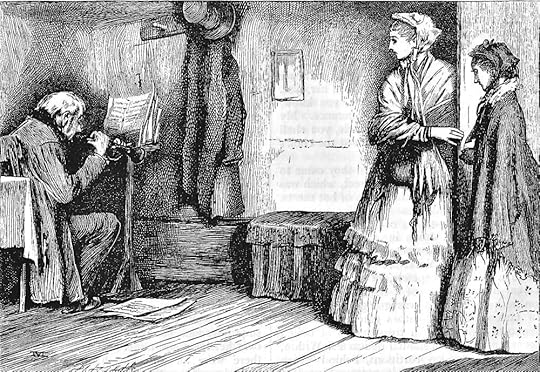

The Dorrit Brothers in the Marshalsea

Chapter 19, Book 1

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

The brothers William and Frederick Dorrit, walking up and down the College-yard — of course on the aristocratic or Pump side, for the Father made it a point of his state to be chary of going among his children on the Poor side, except on Sunday mornings, Christmas Days, and other occasions of ceremony, in the observance whereof he was very punctual, and at which times he laid his hand upon the heads of their infants, and blessed those young insolvents with a benignity that was highly edifying — the brothers, walking up and down the College-yard together, were a memorable sight. Frederick the free, was so humbled, bowed, withered, and faded; William the bond, was so courtly, condescending, and benevolently conscious of a position; that in this regard only, if in no other, the brothers were a spectacle to wonder at.

Commentary:

Furniss's re-interpretation of the Dorrit brothers in the scenes leading up to William Dorrit's apotheosis is based less on both Mahoney's scene of Marshalsea yard, and more on the Phiz original, "The Brothers" for Book 1, Ch. 19. Avoiding the same scene of departure drafted so effectively by Phiz and redrafted by James Mahoney to focus on the contrasting figures of the brothers, Furniss sets the Dorrit brothers against a detailed backdrop of the College Yard and in the context of purposeless, tawdry insolvent debtors, still attempting to dress as members of the middle class, but clearly lacking bourgeois work ethic and sense of propriety. Furniss lavishes his attention and satirical pen upon those who gave the place its unsavory reputation. The elder Dorrit, knowledgeable about the place and its inmates, acts as his brother Frederick tour-guide, pointing out features of the Marshalsea and various characters with interesting backgrounds. All the figures in the scene are charged with Furniss's powers of humorous observation and kinetic energy, and yet all are caricatures in contrast to Mahoney's quiet, almost mundane realism.

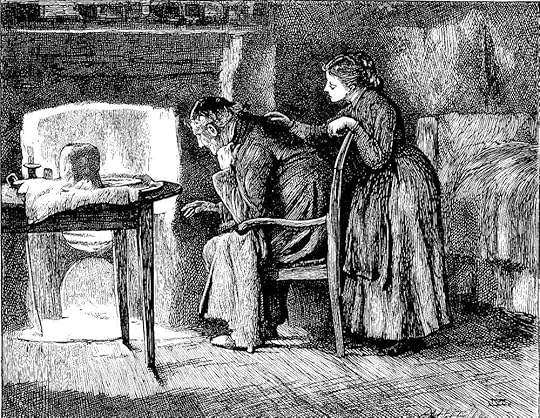

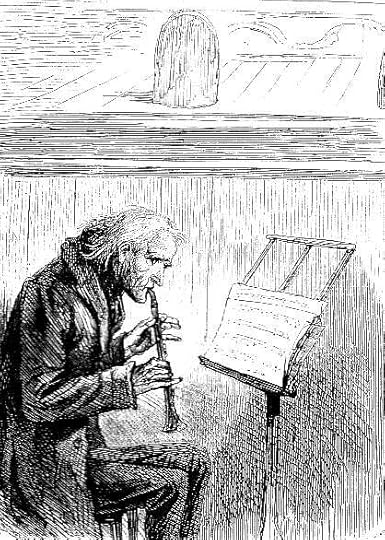

As she stood behind him, leaning over his chair so lovingly, he looked with downcast eyes at the fire.

Chapter 19, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

There, the table was laid for his supper, and his old grey gown was ready for him on his chair-back at the fire. His daughter put her little prayer-book in her pocket — had she been praying for pity on all prisoners and captives! — and rose to welcome him.

Uncle had gone home, then? she asked him as she changed his coat and gave him his black velvet cap. Yes, uncle had gone home. Had her father enjoyed his walk? Why, not much, Amy; not much. No! Did he not feel quite well?

As she stood behind him, leaning over his chair so lovingly, he looked with downcast eyes at the fire. An uneasiness stole over him that was like a touch of shame; and when he spoke, as he presently did, it was in an unconnected and embarrassed manner.

"Something, I — hem! — I don't know what, has gone wrong with Chivery. He is not — ha! — not nearly so obliging and attentive as usual to-night. It — hem! — it's a little thing, but it puts me out, my love. It's impossible to forget," turning his hands over and over and looking closely at them, "that — hem! — that in such a life as mine, I am unfortunately dependent on these men for something every hour in the day."

Her arm was on his shoulder, but she did not look in his face while he spoke. Bending her head she looked another way.. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 19.

Commentary:

The title is somewhat longer in the New York (Harper and Brothers) printing: As she stood behind him, leaning over his chair so lovingly, he looked with downcast eyes at the fire. An uneasiness stole over him that was like a touch of shame; and when he spoke, as he presently did, it was in an unconnected and embarrassed manner — Book 1, chap. 19. The chapter emphasizes Amy's self-sacrificing nature as she ministers to her aged father both night and day, again placing her hand gently on his back to comfort him as she had done for Maggy when they were locked out of the Marshalsea in The gate was so familiar, and so like a companion, that they put down Maggy's basket in a corner to serve for a seat (Book I, chap. 14). The almost sacramental nature of scene is emphasized by the highlighting of the uncut loaf on the table before the Patriarch, the identity suggested by the head-covering of Mr. Dorrit. As is customary for older, middle-class males of the late 1820s, William Dorrit wears a respectable skull-cap (as in the Phiz illustrations of Old Martin in Martin Chuzzlewit, such as Martin Chuzzlewit Suspects The Landlady Without Any Reason). Despite his despondency at having been a prisoner for so long, ironically William Dorrit is comfortably ensconced before a roaring coal-fire, has a dressing-gown, and a dutiful daughter to tend him. In pitying himself, the self-centered father never gives a thought to the cloistered life he has imposed upon his daughter, whose love and affection he quite undervalues.

Although Mahoney does not offer a clue to Amy's especial solicitousness here, she knows the cause of Young Chivery's recent coldness towards her father, for she has without reservation broken off her relationship with that self-styled "lover" in the previous chapter, an incident which Mahoney has realized in "O don't cry!" said Little Dorrit piteously. "Don't, don't! Good-bye, John. God bless you!" "Good-bye, Miss Amy. Good-bye!" And so he left her. Thus, sacrificing herself to her father's comforts commendably has its limits, and she asserts herself sufficiently for the reader to admire her deft handling of the enamored John.

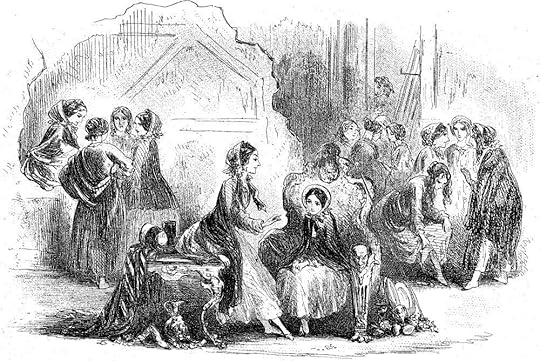

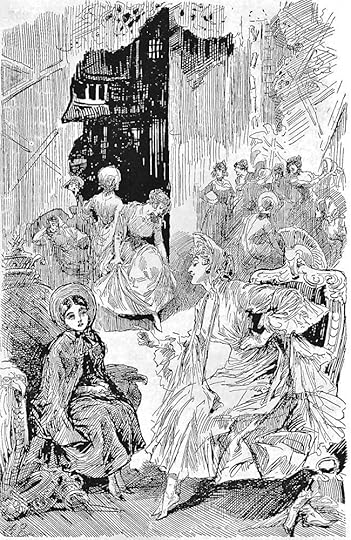

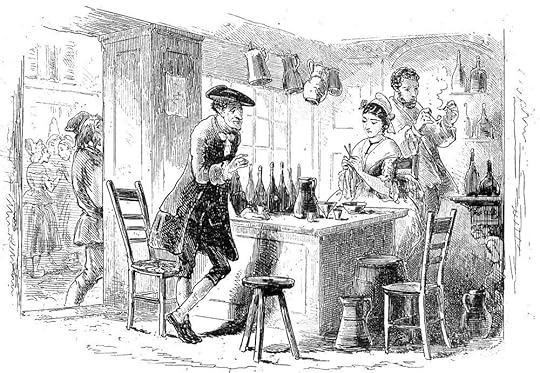

Miss Dorrit and Little Dorrit

Chapter 20

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Well! And what have you got on your mind, Amy? Of course you have got something on your mind about me?" said Fanny. She spoke as if her sister, between two and three years her junior, were her prejudiced grandmother.

"It is not much; but since you told me of the lady who gave you the bracelet, Fanny —"

The monotonous boy put his head round the beam on the left, and said, "Look out there, ladies!" and disappeared. The sprightly gentleman with the black hair as suddenly put his head round the beam on the right, and said, "Look out there, darlings!" and also disappeared. Thereupon all the young ladies rose and began shaking their skirts out behind.

"Well, Amy?" said Fanny, doing as the rest did; "what were you going to say?"

"Since you told me a lady had given you the bracelet you showed me, Fanny, I have not been quite easy on your account, and indeed want to know a little more if you will confide more to me."

"Now, ladies!" said the boy in the Scotch cap. "Now, darlings!" said the gentleman with the black hair. They were every one gone in a moment, and the music and the dancing feet were heard again.

Little Dorrit sat down in a golden chair, made quite giddy by these rapid interruptions. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 20.

Commentary: