The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 1, Chp. 33-36

Chapter 34 is titled "A Shoal of Barnacles" and begins with us learning that the date of the wedding between Pet and Henry has been set. And we are told that the "Barnacles" will be at the wedding:

"There was to be a convocation of Barnacles on the occasion, in order that that very high and very large family might shed as much lustre on the marriage as so dim an event was capable of receiving."

Even though a large number of the Barnacles will be at the wedding not all Barnacles will be there, they are just too numerous to be contained in a building. Also, being public servants, they are dispersed all over the world, "wherever there was a square yard of ground in British occupation under the sun or moon" there was a Barnacle." We're told that during this time Mrs. Gowan makes frequent visits to Mr. Meagles to add names to the guest list and that Mr. Meagles is usually busy examining and paying the debts of his future son-in-law. Arthur has promised to come to the wedding because of his vow of never failing to do Minnie a service, but Daniel Doyce does not want to attend. He so wants to avoid the wedding that he even goes to talk to Mr. Meagles about it:

"he begged, with the freedom of an old friend, and as a favour to one, that he might not be invited. 'For,' said he, 'as my business with this set of gentlemen was to do a public duty and a public service, and as their business with me was to prevent it by wearing my soul out, I think we had better not eat and drink together with a show of being of one mind.'"

Meanwhile, Gowen tells Arthur that he is a disappointed man, he belongs to a family that could have provided for him but hadn't done it. Of course he knows he is fortunate in having Minnie love him and of having such a wealthly father-in-law, but still the Barnacles disappointed him. Also, Gowan doesn't think he will be able to keep at his profession, it takes too much dedication and takes too much time away from leisure activites, this guy is a jerk:

"I hope I may not break down in that; but there, my being a disappointed man may show itself. I may not be able to face it out gravely enough. Between you and me, I think there is some danger of my being just enough soured not to be able to do that.'

'To do what?' asked Clennam.

'To keep it up. To help myself in my turn, as the man before me helps himself in his, and pass the bottle of smoke. To keep up the pretence as to labour, and study, and patience, and being devoted to my art, and giving up many solitary days to it, and abandoning many pleasures for it, and living in it, and all the rest of it—in short, to pass the bottle of smoke according to rule.'

Oh, and he's lazy too, When the marriage day arrives we get a rather lengthy description of the wedding guests, almost all of them Barnacles, I think Arthur may have been the only one present who wasn't a Barnacle, him and the ones paying for all this. There were all sorts of Barnacles, such as Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle who had risen to official heights on the wings of one indignant idea which was:

"to set bounds to the philanthropy, to cramp the charity, to fetter the public spirit, to contract the enterprise, to damp the independent self-reliance, of its people."

There was a young Barnacle, a lively one, Barnacle Junior, William Barnacle, Mr. Tite Barnacle, all sorts of Barnacles, and to tell the truth I got tired of reading about them and since so much of the chapter was reading about them I got tired of reading the chapter. But as I said, the wedding does come to an end and with the departure of Minnie/Pet and Henry comes the departure of all the Barnacles. Although I was bored spending the entire chapter with the Barnacles, Mr. Meagles wasn't, at least he was cheered up by the thought of them being there. Uh, okay. The chapter ends:

'It's very gratifying, Arthur,' he said, 'after all, to look back upon.'

'The past?' said Clennam.

'Yes—but I mean the company.'

It had made him much more low and unhappy at the time, but now it really did him good. 'It's very gratifying,' he said, often repeating the remark in the course of the evening. 'Such high company!'

"There was to be a convocation of Barnacles on the occasion, in order that that very high and very large family might shed as much lustre on the marriage as so dim an event was capable of receiving."

Even though a large number of the Barnacles will be at the wedding not all Barnacles will be there, they are just too numerous to be contained in a building. Also, being public servants, they are dispersed all over the world, "wherever there was a square yard of ground in British occupation under the sun or moon" there was a Barnacle." We're told that during this time Mrs. Gowan makes frequent visits to Mr. Meagles to add names to the guest list and that Mr. Meagles is usually busy examining and paying the debts of his future son-in-law. Arthur has promised to come to the wedding because of his vow of never failing to do Minnie a service, but Daniel Doyce does not want to attend. He so wants to avoid the wedding that he even goes to talk to Mr. Meagles about it:

"he begged, with the freedom of an old friend, and as a favour to one, that he might not be invited. 'For,' said he, 'as my business with this set of gentlemen was to do a public duty and a public service, and as their business with me was to prevent it by wearing my soul out, I think we had better not eat and drink together with a show of being of one mind.'"

Meanwhile, Gowen tells Arthur that he is a disappointed man, he belongs to a family that could have provided for him but hadn't done it. Of course he knows he is fortunate in having Minnie love him and of having such a wealthly father-in-law, but still the Barnacles disappointed him. Also, Gowan doesn't think he will be able to keep at his profession, it takes too much dedication and takes too much time away from leisure activites, this guy is a jerk:

"I hope I may not break down in that; but there, my being a disappointed man may show itself. I may not be able to face it out gravely enough. Between you and me, I think there is some danger of my being just enough soured not to be able to do that.'

'To do what?' asked Clennam.

'To keep it up. To help myself in my turn, as the man before me helps himself in his, and pass the bottle of smoke. To keep up the pretence as to labour, and study, and patience, and being devoted to my art, and giving up many solitary days to it, and abandoning many pleasures for it, and living in it, and all the rest of it—in short, to pass the bottle of smoke according to rule.'

Oh, and he's lazy too, When the marriage day arrives we get a rather lengthy description of the wedding guests, almost all of them Barnacles, I think Arthur may have been the only one present who wasn't a Barnacle, him and the ones paying for all this. There were all sorts of Barnacles, such as Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle who had risen to official heights on the wings of one indignant idea which was:

"to set bounds to the philanthropy, to cramp the charity, to fetter the public spirit, to contract the enterprise, to damp the independent self-reliance, of its people."

There was a young Barnacle, a lively one, Barnacle Junior, William Barnacle, Mr. Tite Barnacle, all sorts of Barnacles, and to tell the truth I got tired of reading about them and since so much of the chapter was reading about them I got tired of reading the chapter. But as I said, the wedding does come to an end and with the departure of Minnie/Pet and Henry comes the departure of all the Barnacles. Although I was bored spending the entire chapter with the Barnacles, Mr. Meagles wasn't, at least he was cheered up by the thought of them being there. Uh, okay. The chapter ends:

'It's very gratifying, Arthur,' he said, 'after all, to look back upon.'

'The past?' said Clennam.

'Yes—but I mean the company.'

It had made him much more low and unhappy at the time, but now it really did him good. 'It's very gratifying,' he said, often repeating the remark in the course of the evening. 'Such high company!'

Chapter 35 is titled "What was Behind Mr. Pancks on Little Dorrit's Hand" , a title I had to read a few times until it made some sort of sense to me. The chapter starts with Mr. Pancks revealing to Arthur the discovery he has made regarding the Dorrit family:

"It was at this time that Mr Pancks, in discharge of his compact with Clennam, revealed to him the whole of his gipsy story, and told him Little Dorrit's fortune. Her father was heir-at-law to a great estate that had long lain unknown of, unclaimed, and accumulating. His right was now clear, nothing interposed in his way, the Marshalsea gates stood open, the Marshalsea walls were down, a few flourishes of his pen, and he was extremely rich."

Pancks says he "moles it out" with the help of his landlord, Mr. Rugg and John Chivery, knowing his devotion to Amy. Now all the paperwork is done and he is ready for the secret to be made known, he came to Arthur first as he had promised. It is during this conversation I find that, although I am a fan of Flora's, at least if she doesn't talk to much, her father - the fine, old fellow - is another story:

'Clennam, who had been almost incessantly shaking hands with him throughout the narrative, was reminded by this to say, in an amazement which even the preparation he had had for the main disclosure smoothed down, 'My dear Mr Pancks, this must have cost you a great sum of money.'

'Pretty well, sir,' said the triumphant Pancks. 'No trifle, though we did it as cheap as it could be done. And the outlay was a difficulty, let me tell you.'

'A difficulty!' repeated Clennam. 'But the difficulties you have so wonderfully conquered in the whole business!' shaking his hand again.

'I'll tell you how I did it,' said the delighted Pancks, putting his hair into a condition as elevated as himself. 'First, I spent all I had of my own. That wasn't much.'

'I am sorry for it,' said Clennam: 'not that it matters now, though. Then, what did you do?'

'Then,' answered Pancks, 'I borrowed a sum of my proprietor.'

'Of Mr Casby?' said Clennam. 'He's a fine old fellow.'

'Noble old boy; an't he?' said Mr Pancks, entering on a series of the dryest snorts. 'Generous old buck. Confiding old boy. Philanthropic old buck. Benevolent old boy! Twenty per cent. I engaged to pay him, sir. But we never do business for less at our shop.'

Arthur felt an awkward consciousness of having, in his exultant condition, been a little premature.

'I said to that boiling-over old Christian,' Mr Pancks pursued, appearing greatly to relish this descriptive epithet, 'that I had got a little project on hand; a hopeful one; I told him a hopeful one; which wanted a certain small capital. I proposed to him to lend me the money on my note. Which he did, at twenty; sticking the twenty on in a business-like way, and putting it into the note, to look like a part of the principal. If I had broken down after that, I should have been his grubber for the next seven years at half wages and double grind. But he's a perfect Patriarch; and it would do a man good to serve him on such terms—on any terms.'

Arthur for his life could not have said with confidence whether Pancks really thought so or not."

And now Arthur goes to the house of Mr. Casby where Little Dorrit will be, although how Arthur knows this I'm not sure, perhaps it is a regular thing for her to be there at the same time each week, I can't remember. When he tells Little Dorrit that her father will be free and will be a rich man she faints. Flora comes in the room to take care of her as only Flora could:

"Upon which Flora returned to take care of her, and hovered about her on a sofa, intermingling kind offices and incoherent scraps of conversation in a manner so confounding, that whether she pressed the Marshalsea to take a spoonful of unclaimed dividends, for it would do her good; or whether she congratulated Little Dorrit's father on coming into possession of a hundred thousand smelling-bottles; or whether she explained that she put seventy-five thousand drops of spirits of lavender on fifty thousand pounds of lump sugar, and that she entreated Little Dorrit to take that gentle restorative; or whether she bathed the foreheads of Doyce and Clennam in vinegar, and gave the late Mr F. more air; no one with any sense of responsibility could have undertaken to decide."

When Amy awakes, she thinks only of her father, of course. We're told that she wants to get to her father to give him the good new and not leave him in jail a moment more than he has to be. She seems uncomfortable and frightened with the idea of being wealthy for herself, but she sheds tears of joy about it for her father’s sake. She certainly likes her father more than I do, but I suppose she would, he is her father after all.

They go to the Marshalsea and tell Mr. Dorrit the news. He is stunned and doesn't say a word until Arthur fetches some wine, Arthur tells the gathering crowd outside that Mr. Dorrit has succeeded to a fortune.

Arthur tells Mr. Dorrit what Mr. Pancks had done on his behalf. Mr. Dorrit agrees to not only reward him generously but everyone else concerned. He then appears at the window and the people in the yard cheer for the Father of the Marshalsea, which is just what he expected they would do. Finally he lays down and falls asleep and Amy asks Arthur to stay and talk, I found her thoughts interesting when she asks Arthur whether her father will pay all his debts before he leaves:

'It seems to me hard,' said Little Dorrit, 'that he should have lost so many years and suffered so much, and at last pay all the debts as well. It seems to me hard that he should pay in life and money both.'

Looking at it from her point of view, I find it seems hard to me too and I can't stand the guy. Shortly after this Amy lays her head on her father's pillow and falls asleep and Clennam quietly leaves the room and the prison.

"It was at this time that Mr Pancks, in discharge of his compact with Clennam, revealed to him the whole of his gipsy story, and told him Little Dorrit's fortune. Her father was heir-at-law to a great estate that had long lain unknown of, unclaimed, and accumulating. His right was now clear, nothing interposed in his way, the Marshalsea gates stood open, the Marshalsea walls were down, a few flourishes of his pen, and he was extremely rich."

Pancks says he "moles it out" with the help of his landlord, Mr. Rugg and John Chivery, knowing his devotion to Amy. Now all the paperwork is done and he is ready for the secret to be made known, he came to Arthur first as he had promised. It is during this conversation I find that, although I am a fan of Flora's, at least if she doesn't talk to much, her father - the fine, old fellow - is another story:

'Clennam, who had been almost incessantly shaking hands with him throughout the narrative, was reminded by this to say, in an amazement which even the preparation he had had for the main disclosure smoothed down, 'My dear Mr Pancks, this must have cost you a great sum of money.'

'Pretty well, sir,' said the triumphant Pancks. 'No trifle, though we did it as cheap as it could be done. And the outlay was a difficulty, let me tell you.'

'A difficulty!' repeated Clennam. 'But the difficulties you have so wonderfully conquered in the whole business!' shaking his hand again.

'I'll tell you how I did it,' said the delighted Pancks, putting his hair into a condition as elevated as himself. 'First, I spent all I had of my own. That wasn't much.'

'I am sorry for it,' said Clennam: 'not that it matters now, though. Then, what did you do?'

'Then,' answered Pancks, 'I borrowed a sum of my proprietor.'

'Of Mr Casby?' said Clennam. 'He's a fine old fellow.'

'Noble old boy; an't he?' said Mr Pancks, entering on a series of the dryest snorts. 'Generous old buck. Confiding old boy. Philanthropic old buck. Benevolent old boy! Twenty per cent. I engaged to pay him, sir. But we never do business for less at our shop.'

Arthur felt an awkward consciousness of having, in his exultant condition, been a little premature.

'I said to that boiling-over old Christian,' Mr Pancks pursued, appearing greatly to relish this descriptive epithet, 'that I had got a little project on hand; a hopeful one; I told him a hopeful one; which wanted a certain small capital. I proposed to him to lend me the money on my note. Which he did, at twenty; sticking the twenty on in a business-like way, and putting it into the note, to look like a part of the principal. If I had broken down after that, I should have been his grubber for the next seven years at half wages and double grind. But he's a perfect Patriarch; and it would do a man good to serve him on such terms—on any terms.'

Arthur for his life could not have said with confidence whether Pancks really thought so or not."

And now Arthur goes to the house of Mr. Casby where Little Dorrit will be, although how Arthur knows this I'm not sure, perhaps it is a regular thing for her to be there at the same time each week, I can't remember. When he tells Little Dorrit that her father will be free and will be a rich man she faints. Flora comes in the room to take care of her as only Flora could:

"Upon which Flora returned to take care of her, and hovered about her on a sofa, intermingling kind offices and incoherent scraps of conversation in a manner so confounding, that whether she pressed the Marshalsea to take a spoonful of unclaimed dividends, for it would do her good; or whether she congratulated Little Dorrit's father on coming into possession of a hundred thousand smelling-bottles; or whether she explained that she put seventy-five thousand drops of spirits of lavender on fifty thousand pounds of lump sugar, and that she entreated Little Dorrit to take that gentle restorative; or whether she bathed the foreheads of Doyce and Clennam in vinegar, and gave the late Mr F. more air; no one with any sense of responsibility could have undertaken to decide."

When Amy awakes, she thinks only of her father, of course. We're told that she wants to get to her father to give him the good new and not leave him in jail a moment more than he has to be. She seems uncomfortable and frightened with the idea of being wealthy for herself, but she sheds tears of joy about it for her father’s sake. She certainly likes her father more than I do, but I suppose she would, he is her father after all.

They go to the Marshalsea and tell Mr. Dorrit the news. He is stunned and doesn't say a word until Arthur fetches some wine, Arthur tells the gathering crowd outside that Mr. Dorrit has succeeded to a fortune.

Arthur tells Mr. Dorrit what Mr. Pancks had done on his behalf. Mr. Dorrit agrees to not only reward him generously but everyone else concerned. He then appears at the window and the people in the yard cheer for the Father of the Marshalsea, which is just what he expected they would do. Finally he lays down and falls asleep and Amy asks Arthur to stay and talk, I found her thoughts interesting when she asks Arthur whether her father will pay all his debts before he leaves:

'It seems to me hard,' said Little Dorrit, 'that he should have lost so many years and suffered so much, and at last pay all the debts as well. It seems to me hard that he should pay in life and money both.'

Looking at it from her point of view, I find it seems hard to me too and I can't stand the guy. Shortly after this Amy lays her head on her father's pillow and falls asleep and Clennam quietly leaves the room and the prison.

Our last chapter of this installment is Chapter 36 titled "The Marshalsea becomes an Orphan" and it is the day that the Dorrits walk out of prison for the last time, hopefully the last time. We're told that the time they had to wait had been short but Mr. Dorrit had complained much about the wait. Of course he did, what else would he do? He complains to Mr. Rugg about the delay threatening to employ someone else to do the job, telling him to do his job and to do it with promptitude. This is one of the men who worked so hard to get him released in the first place and Mr Dorrit is telling him to do his job with promptitude? I like him less and less each time I see him.

We're told that the Collegians aren't envious, some had a regard for the Dorrits, others felt that it could someday also happen to them, and others were pleased that the event and the Marshalsea had made it into the newspapers. I would have just been glad to get rid of him, but that's just me. They even get him a parting gift, which we're told, was never displayed in the family mansion or found among the family papers. He assured them in a "royal manner" of course that he believed they were sincere and that they should all try to follow his example. Oh please, spare me that.

He even gives them a "comprehensive entertainment" which he doesn't attend because his dinners are brought from the hotel now, but Tip represents the family and the Father shows up to drink a toast with them at the end. And now the day arrives and they are leaving the Marshalsea, all the collegians and turnkeys are present wearing their best clothing, whatever that may be. Mr. Dorrit and his brother Frederick walk out arm in arm and Mr. Dorrit asks his brother to try to put a little polish in his demeanor. When Frederick asks him how he should do it Mr. Dorrit tells him to think of what he himself is thinking, and when Frederick asks what he is thinking I could almost hear Tristram grumbling at the answer:

"'Oh! my dear Frederick, how can I answer you? I can only say what, in leaving these good people, I think myself.'

'That's it!' cried his brother. 'That will help me.'

'I find that I think, my dear Frederick, and with mixed emotions in which a softened compassion predominates, What will they do without me!'

'True,' returned his brother. 'Yes, yes, yes, yes. I'll think that as we go, What will they do without my brother! Poor things! What will they do without him!'

And now we are almost out the door, William and Frederick in the lead followed by Edward (Tip) and Fanny, then Mr. Plornish and Maggy who are carrying all the family's goods they had decided to bring with them. And every collegian, and every turnkey, and every family of every collegian, and lots of other people are there to watch the big event:

"There, were the people who were always going out to-morrow, and always putting it off; there, were the people who had come in yesterday, and who were much more jealous and resentful of this freak of fortune than the seasoned birds. There, were some who, in pure meanness of spirit, cringed and bowed before the enriched Collegian and his family; there, were others who did so really because their eyes, accustomed to the gloom of their imprisonment and poverty, could not support the light of such bright sunshine. There, were many whose shillings had gone into his pocket to buy him meat and drink; but none who were now obtrusively Hail fellow well met! with him, on the strength of that assistance. It was rather to be remarked of the caged birds, that they were a little shy of the bird about to be so grandly free, and that they had a tendency to withdraw themselves towards the bars, and seem a little fluttered as he passed."

It is only when they are all in the carriage that they realize Amy is not with them. The chapter ends with this:

'I do say,' she repeated, 'this is perfectly infamous! Really almost enough, even at such a time as this, to make one wish one was dead! Here is that child Amy, in her ugly old shabby dress, which she was so obstinate about, Pa, which I over and over again begged and prayed her to change, and which she over and over again objected to, and promised to change to-day, saying she wished to wear it as long as ever she remained in there with you—which was absolutely romantic nonsense of the lowest kind—here is that child Amy disgracing us to the last moment and at the last moment, by being carried out in that dress after all. And by that Mr Clennam too!'

The offence was proved, as she delivered the indictment. Clennam appeared at the carriage-door, bearing the little insensible figure in his arms.

'She has been forgotten,' he said, in a tone of pity not free from reproach. 'I ran up to her room (which Mr Chivery showed me) and found the door open, and that she had fainted on the floor, dear child. She appeared to have gone to change her dress, and to have sunk down overpowered. It may have been the cheering, or it may have happened sooner. Take care of this poor cold hand, Miss Dorrit. Don't let it fall.'

'Thank you, sir,' returned Miss Dorrit, bursting into tears. 'I believe I know what to do, if you will give me leave. Dear Amy, open your eyes, that's a love! Oh, Amy, Amy, I really am so vexed and ashamed! Do rouse yourself, darling! Oh, why are they not driving on! Pray, Pa, do drive on!'

The attendant, getting between Clennam and the carriage-door, with a sharp 'By your leave, sir!' bundled up the steps, and they drove away."

Good riddance.

We're told that the Collegians aren't envious, some had a regard for the Dorrits, others felt that it could someday also happen to them, and others were pleased that the event and the Marshalsea had made it into the newspapers. I would have just been glad to get rid of him, but that's just me. They even get him a parting gift, which we're told, was never displayed in the family mansion or found among the family papers. He assured them in a "royal manner" of course that he believed they were sincere and that they should all try to follow his example. Oh please, spare me that.

He even gives them a "comprehensive entertainment" which he doesn't attend because his dinners are brought from the hotel now, but Tip represents the family and the Father shows up to drink a toast with them at the end. And now the day arrives and they are leaving the Marshalsea, all the collegians and turnkeys are present wearing their best clothing, whatever that may be. Mr. Dorrit and his brother Frederick walk out arm in arm and Mr. Dorrit asks his brother to try to put a little polish in his demeanor. When Frederick asks him how he should do it Mr. Dorrit tells him to think of what he himself is thinking, and when Frederick asks what he is thinking I could almost hear Tristram grumbling at the answer:

"'Oh! my dear Frederick, how can I answer you? I can only say what, in leaving these good people, I think myself.'

'That's it!' cried his brother. 'That will help me.'

'I find that I think, my dear Frederick, and with mixed emotions in which a softened compassion predominates, What will they do without me!'

'True,' returned his brother. 'Yes, yes, yes, yes. I'll think that as we go, What will they do without my brother! Poor things! What will they do without him!'

And now we are almost out the door, William and Frederick in the lead followed by Edward (Tip) and Fanny, then Mr. Plornish and Maggy who are carrying all the family's goods they had decided to bring with them. And every collegian, and every turnkey, and every family of every collegian, and lots of other people are there to watch the big event:

"There, were the people who were always going out to-morrow, and always putting it off; there, were the people who had come in yesterday, and who were much more jealous and resentful of this freak of fortune than the seasoned birds. There, were some who, in pure meanness of spirit, cringed and bowed before the enriched Collegian and his family; there, were others who did so really because their eyes, accustomed to the gloom of their imprisonment and poverty, could not support the light of such bright sunshine. There, were many whose shillings had gone into his pocket to buy him meat and drink; but none who were now obtrusively Hail fellow well met! with him, on the strength of that assistance. It was rather to be remarked of the caged birds, that they were a little shy of the bird about to be so grandly free, and that they had a tendency to withdraw themselves towards the bars, and seem a little fluttered as he passed."

It is only when they are all in the carriage that they realize Amy is not with them. The chapter ends with this:

'I do say,' she repeated, 'this is perfectly infamous! Really almost enough, even at such a time as this, to make one wish one was dead! Here is that child Amy, in her ugly old shabby dress, which she was so obstinate about, Pa, which I over and over again begged and prayed her to change, and which she over and over again objected to, and promised to change to-day, saying she wished to wear it as long as ever she remained in there with you—which was absolutely romantic nonsense of the lowest kind—here is that child Amy disgracing us to the last moment and at the last moment, by being carried out in that dress after all. And by that Mr Clennam too!'

The offence was proved, as she delivered the indictment. Clennam appeared at the carriage-door, bearing the little insensible figure in his arms.

'She has been forgotten,' he said, in a tone of pity not free from reproach. 'I ran up to her room (which Mr Chivery showed me) and found the door open, and that she had fainted on the floor, dear child. She appeared to have gone to change her dress, and to have sunk down overpowered. It may have been the cheering, or it may have happened sooner. Take care of this poor cold hand, Miss Dorrit. Don't let it fall.'

'Thank you, sir,' returned Miss Dorrit, bursting into tears. 'I believe I know what to do, if you will give me leave. Dear Amy, open your eyes, that's a love! Oh, Amy, Amy, I really am so vexed and ashamed! Do rouse yourself, darling! Oh, why are they not driving on! Pray, Pa, do drive on!'

The attendant, getting between Clennam and the carriage-door, with a sharp 'By your leave, sir!' bundled up the steps, and they drove away."

Good riddance.

Kim wrote: "Although I was bored spending the entire chapter with the Barnacles, Mr. Meagles wasn't, at least he was cheered up by the thought of them being there."

Kim wrote: "Although I was bored spending the entire chapter with the Barnacles, Mr. Meagles wasn't, at least he was cheered up by the thought of them being there."I skimmed the Barnacles section. I find the plot cooks along just fine without them, and they became an overdone joke pretty fast for me.

But I wonder if the quote you pulled above is my answer to the question of why on earth did Meagles ever consent to this marriage? Maybe because he's impressed by nobility?

It still makes no sense though, because if he actually thought it was a good match he should be happier about it. His consent seems like a significant logical flaw in the story.

Kim wrote: "To keep it up. To help myself in my turn, as the man before me helps himself in his, and pass the bottle of smoke. To keep up the pretence as to labour, and study, and patience, and being devoted to my art, and giving up many solitary days to it, and abandoning many pleasures for it, and living in it, and all the rest of it—in short, to pass the bottle of smoke according to rule."

Kim wrote: "To keep it up. To help myself in my turn, as the man before me helps himself in his, and pass the bottle of smoke. To keep up the pretence as to labour, and study, and patience, and being devoted to my art, and giving up many solitary days to it, and abandoning many pleasures for it, and living in it, and all the rest of it—in short, to pass the bottle of smoke according to rule."I'm very intrigued by this expression "pass the bottle of smoke." I take it to be some sort of corruption of the idea that we should do our best to take what previous generations left to us and pass it on to the next generation: do our work, pass along the benefits. Except in this case it's pass the bottle--which might be a nice sharing thing to do or might be passing on a drinking habit, not so nice; but then it's pass the bottle of smoke--so there's not even drink there. It's just passing on an illusion that we ought to be useful, when that's nonsense. Or at least Gowan finds it nonsense.

Kim wrote: "Give these people names like Merdle and Meagles, then have Mrs. Gowen refer to the Meagles as Miggleses, and I'm confused. "

Kim wrote: "Give these people names like Merdle and Meagles, then have Mrs. Gowen refer to the Meagles as Miggleses, and I'm confused. "It's true. I was thrown by the beginning of the chapter and could not remember who the Miggleses were.

Mrs. Gowen and Mrs. Merdle the bosom made me laugh, however:

‘From what I can make out,’ said Mrs Gowan, ‘I believe I may say that Henry will be relieved from debt—’

‘Much in debt?’ asked Mrs Merdle through her eyeglass.

‘Why tolerably, I should think,’ said Mrs Gowan.

I also enjoyed, regarding the Minipet wedding, how Doyce's position was "how 'bout I just pass on this one, anybody mind?" He does stand out in this book as a sensible person.

I also enjoyed, regarding the Minipet wedding, how Doyce's position was "how 'bout I just pass on this one, anybody mind?" He does stand out in this book as a sensible person.

Yes, he does stand out to be very sensible.

And I will repeat what I already mentioned in the previous thread: what if Amy had said 'yes' to John? Would she then have been berated because she brings the family down about that now they are rich? Or would they just conveniently have forgotten that she belongs to the family too, just like they almost forgot her anyway, now that they have other servants to take care of their basic needs?

I wonder if this all ends well. I can't imagine Mr. Dorrit will be good with money after being in the Marshalsea and not showing any sign of knowing where even his food comes from for more than 20 years. And then there are Fanny and Tip who have never learned to be smart with their money, and who have always put the emphasis on keeping up appearances.

And I will repeat what I already mentioned in the previous thread: what if Amy had said 'yes' to John? Would she then have been berated because she brings the family down about that now they are rich? Or would they just conveniently have forgotten that she belongs to the family too, just like they almost forgot her anyway, now that they have other servants to take care of their basic needs?

I wonder if this all ends well. I can't imagine Mr. Dorrit will be good with money after being in the Marshalsea and not showing any sign of knowing where even his food comes from for more than 20 years. And then there are Fanny and Tip who have never learned to be smart with their money, and who have always put the emphasis on keeping up appearances.

Jantine wrote: "Yes, he does stand out to be very sensible.

And I will repeat what I already mentioned in the previous thread: what if Amy had said 'yes' to John? Would she then have been berated because she brin..."

Hi Jantine

Yes. I could see the family turning on Amy if she accepted John’s proposal. They seem unable to look beyond their own noses in the best of times.

But then we must remember that Amy said a clear no herself. Is this the first time we have seen Amy take a clear and unequivocal position on anything pertaining to her own needs and wants? By saying no to one offer of marriage she is keeping the door open for another … ;-)

And I will repeat what I already mentioned in the previous thread: what if Amy had said 'yes' to John? Would she then have been berated because she brin..."

Hi Jantine

Yes. I could see the family turning on Amy if she accepted John’s proposal. They seem unable to look beyond their own noses in the best of times.

But then we must remember that Amy said a clear no herself. Is this the first time we have seen Amy take a clear and unequivocal position on anything pertaining to her own needs and wants? By saying no to one offer of marriage she is keeping the door open for another … ;-)

Along the same line of what-ifs, I wonder if Amy would have accepted John's proposal had she not yet met Arthur, or would she has been equally as adamant in her refusal?

Along the same line of what-ifs, I wonder if Amy would have accepted John's proposal had she not yet met Arthur, or would she has been equally as adamant in her refusal?

Mary Lou wrote: "Along the same line of what-ifs, I wonder if Amy would have accepted John's proposal had she not yet met Arthur, or would she has been equally as adamant in her refusal?"

Mary Lou

Good point. Without Arthur in the picture a marriage to John would be advantageous. Amy would have her own matrimonial home with a view in the Marshalsea, her husband’s future in the Marshalsea would be seen as an advantage to Mr Dorrit and if she became a housewife she would never need to leave the Marshalsea. What a charmed life. Yikes!

Just think if Mr Dorrit did receive his good fortune. Poor Little Dorrit. Thanks for the “what-if.” Speculation is fun.

Mary Lou

Good point. Without Arthur in the picture a marriage to John would be advantageous. Amy would have her own matrimonial home with a view in the Marshalsea, her husband’s future in the Marshalsea would be seen as an advantage to Mr Dorrit and if she became a housewife she would never need to leave the Marshalsea. What a charmed life. Yikes!

Just think if Mr Dorrit did receive his good fortune. Poor Little Dorrit. Thanks for the “what-if.” Speculation is fun.

I'm back to hating the Barnacle (Oodle, Toodle...) chapters, and wondering what was different about the first one in this book, which I enjoyed. I think I've figured it out.

I'm back to hating the Barnacle (Oodle, Toodle...) chapters, and wondering what was different about the first one in this book, which I enjoyed. I think I've figured it out. Most of the chapters in which Dickens personifies systems are generally written as commentary by the narrator. They can be boring and sermonizing (is that a word?), despite Dickens attempts to make them humorous. But when we first met the Barnacles, it was through Arthur's direct interactions, and we experience the bureaucracy alongside him. Being flies on the wall as he meets one-on-one with the Barnacles, and having had our own similar experiences, not only incorporates these symbolic characters into the story more effectively, but makes the narrative much more engaging.

In this week's chapters, Dickens went back to telling, instead of showing. We never really see the Barnacles converse with the other wedding guests (just as the interactions with the Merdles and their guests - Treasury, Bishop, etc. - are described to us rather than witnessed by us) The most we get is a quick glimpse of them complaining to one another about Arthur's "wanting to know, you know." As representations of government bureaucracy and nepotism, they are two dimensional. When they were interacting directly with Arthur, they - for a moment - became actual, three-dimensional characters. I guess Dickens was worried that if they became individuals in their own right, it might somehow water down his bigger message.

Mary Lou wrote: "I'm back to hating the Barnacle (Oodle, Toodle...) chapters, and wondering what was different about the first one in this book, which I enjoyed. I think I've figured it out.

Mary Lou wrote: "I'm back to hating the Barnacle (Oodle, Toodle...) chapters, and wondering what was different about the first one in this book, which I enjoyed. I think I've figured it out. Most of the chapters ..."

I think you're right, but I also think it's just overkill, since we already met them before and how much do we need more of the same thing?

Mary Lou wrote: "Along the same line of what-ifs, I wonder if Amy would have accepted John's proposal had she not yet met Arthur, or would she has been equally as adamant in her refusal?"

Mary Lou wrote: "Along the same line of what-ifs, I wonder if Amy would have accepted John's proposal had she not yet met Arthur, or would she has been equally as adamant in her refusal?"I figured the whole John storyline was there just to foreshadow that Amy has Given Her Heart via her refusal. I find John entertaining and I'm glad he's there, but he doesn't serve any other plot purpose. Pancks is perfectly capable of tracking down the Dorrits' inheritance on his own. And the John proposal scene comes while Arthur is still pining over Minipet, so readers need a little hint that the story will come back around to Amy just to keep them going. And it would be her job to keep them going, since a Dickens hero can fall in love (if that's what it is) repeatedly, but a heroine only once.

Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Along the same line of what-ifs, I wonder if Amy would have accepted John's proposal had she not yet met Arthur, or would she has been equally as adamant in her refusal?"

I figure..."

Hi Julie

Thanks for the insight that a hero can fall in love many times but a heroine only once.

Such a plot repetition throughout Dickens’s novels tells us much both about the times and the author.

I figure..."

Hi Julie

Thanks for the insight that a hero can fall in love many times but a heroine only once.

Such a plot repetition throughout Dickens’s novels tells us much both about the times and the author.

Julie wrote: "since a Dickens hero can fall in love (if that's what it is) repeatedly, but a heroine only once."

Like Peter, I really love this sentence and find that there is a lot of truth in it, not only as far as Dickens is concerned but also in connection with many other Victorian writers (often male ones), who tend to put the heroine on a pedestal, whose inscriptions read, "Forbearance, patience, and self-denial". I think we see this kind of thinking at work even today, when it is quite often assumed that a young man has to sow his wild oats before he settles down, whereas a girl who wants to sow her wild oats is often given a bad name.

Did any of you find it strange that when Pancks had found out all those things about the Dorrits and their claim to a large fortune, it was not the man himself who went to tell the family, and, first of all, Amy - but Arthur, who did not lift a finger in the entire affair? What business did Arthur have to do this? Our narrator remarks that when the Dorrits leave the prison, there is Mr. Casby, spreading benevolence, and being credited, by many people, with having made it all possible. Clearly, the narrator means us to be indignant at the old humbug for harvesting where he did not sow, but frankly speaking, Arthur is doing the same thing. In this context, I must once again express my admiration for Mr F.'s aunt, who, with reference to Arthur and the discovery made by Pancks, gives vent to sarcasms like, "Don't believe it's his doing!" or "He needn't take no credit to himself for it!" Now, whereas the vehemence with which the old lady utters this obloquy makes it all quite funny and absurd, I could not help thinking that she was very, very right in saying so. Three cheers for Mr F.'s aunt then!

Like Peter, I really love this sentence and find that there is a lot of truth in it, not only as far as Dickens is concerned but also in connection with many other Victorian writers (often male ones), who tend to put the heroine on a pedestal, whose inscriptions read, "Forbearance, patience, and self-denial". I think we see this kind of thinking at work even today, when it is quite often assumed that a young man has to sow his wild oats before he settles down, whereas a girl who wants to sow her wild oats is often given a bad name.

Did any of you find it strange that when Pancks had found out all those things about the Dorrits and their claim to a large fortune, it was not the man himself who went to tell the family, and, first of all, Amy - but Arthur, who did not lift a finger in the entire affair? What business did Arthur have to do this? Our narrator remarks that when the Dorrits leave the prison, there is Mr. Casby, spreading benevolence, and being credited, by many people, with having made it all possible. Clearly, the narrator means us to be indignant at the old humbug for harvesting where he did not sow, but frankly speaking, Arthur is doing the same thing. In this context, I must once again express my admiration for Mr F.'s aunt, who, with reference to Arthur and the discovery made by Pancks, gives vent to sarcasms like, "Don't believe it's his doing!" or "He needn't take no credit to himself for it!" Now, whereas the vehemence with which the old lady utters this obloquy makes it all quite funny and absurd, I could not help thinking that she was very, very right in saying so. Three cheers for Mr F.'s aunt then!

Interestingly, the first two chapters of this week revert to the question of men and their jobs: I could not help but feel sorry for Mr Merdle, who only reaps thanklessness from his wife, who reproaches him with not leaving his professional cares in the office, as Society demands, and with bringing his troubles and cares home with him, as far as his behaviour is concerned. We don't know anything about his work but that it seems to dampen his spirit and to sit ill with him, and yet, instead of supporting her husband, his wife vilifies him. When he says that he had rather be a carpenter, I felt sorry for Mr Merdle (and also thought of Mr Doyce) because a carpenter does an honest day's work and really produces something, whereas, for all we know, Mr Merdle's business activities might be a sham. Maybe, Mr Merdle would be a lot happier if he were a carpenter and if he had not married such a grand dame as Mrs Merdle.

Similarly, this contrast between really doing something that you dedicate your mind and soul to and social appearances applies to Mr. Gowan, who has another job-related conversation with Arthur. Gowan, however, does not even think of being a carpenter, but clings to his own pretensions.

Another example in this context is Mr Dorrit, who soon begins to treat Mr Rugg and Mr Pancks - the two men who went to great lengths in order to substantiate his claim to the fortune that gets him out of the prison - as his employees, treating them in a very impatient and high-handed manner. And let us not forget that Pancks laid out all his savings in the service of Dorrit - he would have been standing there empty-handed, if his endeavours had come to nothing, and therefore he might have deserved a better treatment by Mr Dorrit.

Similarly, this contrast between really doing something that you dedicate your mind and soul to and social appearances applies to Mr. Gowan, who has another job-related conversation with Arthur. Gowan, however, does not even think of being a carpenter, but clings to his own pretensions.

Another example in this context is Mr Dorrit, who soon begins to treat Mr Rugg and Mr Pancks - the two men who went to great lengths in order to substantiate his claim to the fortune that gets him out of the prison - as his employees, treating them in a very impatient and high-handed manner. And let us not forget that Pancks laid out all his savings in the service of Dorrit - he would have been standing there empty-handed, if his endeavours had come to nothing, and therefore he might have deserved a better treatment by Mr Dorrit.

Tristram wrote: "And let us not forget that Pancks laid out all his savings in the service of Dorrit - he would have been standing there empty-handed, if his endeavours had come to nothing, and therefore he might have deserved a better treatment by Mr Dorrit. "

Tristram wrote: "And let us not forget that Pancks laid out all his savings in the service of Dorrit - he would have been standing there empty-handed, if his endeavours had come to nothing, and therefore he might have deserved a better treatment by Mr Dorrit. "I can't quite make Pancks out! Hoping to learn more.

Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage

Chapter 33, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Mrs. Merdle was at home, and was in her nest of crimson and gold, with the parrot on a neighbouring stem watching her with his head on one side, as if he took her for another splendid parrot of a larger species. To whom entered Mrs. Gowan, with her favourite green fan, which softened the light on the spots of bloom.

"My dear soul," said Mrs Gowan, tapping the back of her friend's hand with this fan after a little indifferent conversation, "you are my only comfort. That affair of Henry's that I told you of, is to take place. Now, how does it strike you? I am dying to know, because you represent and express Society so well."

Mrs. Merdle reviewed the bosom which Society was accustomed to review; and having ascertained that show-window of Mr Merdle's and the London jewellers' to be in good order, replied:

"As to marriage on the part of a man, my dear, Society requires that he should retrieve his fortunes by marriage. Society requires that he should gain by marriage. Society requires that he should found a handsome establishment by marriage. Society does not see, otherwise, what he has to do with marriage. Bird, be quiet!"

For the parrot on his cage above them, presiding over the conference as if he were a judge (and indeed he looked rather like one), had wound up the exposition with a shriek.

"Cases there are," said Mrs. Merdle, delicately crooking the little finger of her favourite hand, and making her remarks neater by that neat action; "cases there are where a man is not young or elegant, and is rich, and has a handsome establishment already. Those are of a different kind. In such cases —"

Mrs. Merdle shrugged her snowy shoulders and put her hand upon the jewel-stand, checking a little cough, as though to add, "why, a man looks out for this sort of thing, my dear." Then the parrot shrieked again, and she put up her glass to look at him, and said, "Bird! Do be quiet!"

"But, young men," resumed Mrs. Merdle, "and by young men you know what I mean, my love — I mean people's sons who have the world before them — they must place themselves in a better position towards Society by marriage, or Society really will not have any patience with their making fools of themselves. Dreadfully worldly all this sounds," said Mrs. Merdle, leaning back in her nest and putting up her glass again, "does itnot?"

"But it is true," said Mrs. Gowan, with a highly moral air. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 33, "Mrs. Merdle's Complaint".

Commentary:

The master-touch is the unsettling presence of the parrot, whose shrieking acts as a counterpoint to Mrs. Merdle's magisterial pronouncements about marriage, as if her own experience somehow renders her an expert. Enshrined in a canopy not unlike that which one sees in the bedroom scenes in the homes of Dickens's more affluent characters, the gilded cage implies the imprisoning nature of society marriage, mocking the conception underlying the supporting cupidon (right) as a god of love, for affection has no part in Mrs. Merdle's marriage calculations, which are entirely premised on property and social acceptability. The specific marriage about which Mrs. Gowan is soliciting Mrs. Merdle's advice is her son's marriage to Pet Meagles, which should have the desired result of enabling the aristocratic Henry Gowan to "retrieve his fortunes" — that is, to be "relieved from debt", of which the profligate amateur artist has no shortage and against which both ladies expect Mr. Meagles to make considerable outlay prior to the wedding. Mrs. Gowan seems not entirely reconciled to Henry's "marrying down," but acknowledges the necessity of his acquiring the additional income, "an allowance of three hundred a year" or more from the bride's father, a middle-class businessman, and therefore (rather like Mr. Merdle) not a person "in Society". Discretely both women are thoroughly aware that, at least financially (and Society is nothing if not mercenary), this is a very good match for spendthrift Henry Gowan.

Once the devious Mrs. Gowan has left, her mission of seeming (as far as Society goes) to having objected mightily to her son's marrying Pet, the nature of the chapter title becomes clear. The banker husband, having returned from the office to wander his mansion aimlessly, stumbles upon the ladies as Mrs. Gowan is leaving. Mrs. Merdle then delivers her famous "complaint" that her feckless husband is not fit for Society because he is utterly lacking in manners and sophistication. This indictment she delivers from her "ottoman," rather than the padded throne in which she is regally ensconced in the illustration, but in other respects the illustration is almost entirely consistent with the text. The other significant discrepancy is the depiction of a thin, elderly Mrs. Gowan, a Hampton Court "grace-and-favour" pensioner with (caustically remarks Dickens) one-and-a-half chins, whereas Phiz's aging widow is thin and has a pointed face. Aside from a cameo in Phiz's "The Family Dignity is Affronted" (October 1856), this the original serial's sole portrait of the epitome of Society and her ample, jewel-bedecked bosom. The curtains in the background imply not so much theatricality as acting or disguising one's true emotions, for Mrs. Gowan (nowhere else depicted in the series) is merely going through the motions of protesting the marriage, and for her part Mrs. Merdle is thoroughly aware that Pet Meagles is a good catch.

Joyful Tidings

Book I Chapter 35

Felix Octavius Carr Darley

Household Edition (1863)

Text Illustrated:

"Compose yourself, sir," said Clennam, "and take a little time to think. To think of the brightest and most fortunate accidents of life. We have all heard of great surprises of joy. They are not at an end, sir. They are rare, but not at an end."

"Mr. Clennam? Not at an end? Not at an end for —" He touched himself upon the breast, instead of saying "me."

"No," returned Clennam.

"What surprise," he asked, keeping his left hand over his heart, and there stopping in his speech, while with his right hand he put his glasses exactly level on the table: "what such surprise can be in store for me?"

"Let me answer with another question. Tell me, Mr Dorrit, what surprise would be the most unlooked for and the most acceptable to you. Do not be afraid to imagine it, or to say what it would be."

He looked steadfastly at Clennam, and, so looking at him, seemed to change into a very old haggard man. The sun was bright upon the wall beyond the window, and on the spikes at top. He slowly stretched out the hand that had been upon his heart, and pointed at the wall.

"It is down," said Clennam. "Gone!"

He remained in the same attitude, looking steadfastly at him.

"And in its place," said Clennam, slowly and distinctly, "are the means to possess and enjoy the utmost that they have so long shut out. Mr Dorrit, there is not the smallest doubt that within a few days you will be free, and highly prosperous. I congratulate you with all my soul on this change of fortune, and on the happy future into which you are soon to carry the treasure you have been blest with here — the best of all the riches you can have elsewhere — the treasure at your side."

With those words, he pressed his hand and released it; and his daughter, laying her face against his, encircled him in the hour of his prosperity with her arms, as she had in the long years of his adversity encircled him with her love and toil and truth; and poured out her full heart in gratitude, hope, joy, blissful ecstasy, and all for him.

"I shall see him as I never saw him yet. I shall see my dear love, with the dark cloud cleared away. I shall see him, as my poor mother saw him long ago. O my dear, my dear! O father, father! O thank God, thank God!"

Commentary:

The scene is the Marshalsea and is the culmination of the novel's first movement, "Poverty." Here, Arthur Clennam, having already broken the news of the inheritance to Amy Dorrit, now imparts to a stunned Father of the Marshalsea, William Dorrit, that (like the novelist's own father, John Dickens) he has come into a bequest to will result in his immediate release from debtors' prison. Whereas Amy's initial response had been to faint, Mr. Dorrit has an involuntary shaking fit because he has become so acclimatized to prison life and has, indeed, built his entire identity on the length of his incarceration. Now, thanks to Pancks's detective work, William Dorrit will be able to adopt the life-style to which he had always aspired. Darley's image of the stunned heir implies that he will always be haunted by the shades of the prison house.

Phiz's The Marshalsea becomes an Orphan (Book One, Chapter 36), realizes the aftermath of the baronial feast that William Dorrit throws for the collegians and the heroic procession out of the prison yard of the Dorrit family; Phiz's preference for showing the group exodus over the intimate scene in which William Dorrit learns of his good fortune in the previous chapter may have been occasioned by the illustrator's already having shown the Dorrit brothers in Chapter 19, The Brothers. Certainly the moving scene that Darley elected to illustrate has no precedent in the original serial, and Darley would not have had access to Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867 Diamond Edition illustration Little Dorrit and Her Father (frontispiece). Although James Mahoney provided an Illustration for Chapter 35 in the 1873 Household Edition, he shows the aftermath of their reception of the good news, when Amy and her father, exhausted, fall asleep, and Arthur Clennam discretely leaves the room. Darley's treatment is particularly effective because of the triangular arrangement of the figures, with the fashionably dressed Clennam at the apex, left, and Amy's skirt leading the eye downward to the base, right. In their emotional throes William Dorrit has dropped his newspaper and Amy her bonnet as her father struggles to understand the great change that providence has wrought upon him and his family.

This is the illustration by Sol Eytinge Jr. that the above commentary on the Darley illustration is referring to:

Little Dorrit and her Father

Sol Eytinge Jr.

"Little Dorrit and Her Father, Diamond edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1871)

Commentary:

The dual character study is different from others in Eytinge's Diamond Edition sequences of sixteen for each volume in that it post-dates Eytinge's 1869 visit to London and Gadshill. As is typical of these studies, Eytinge appears to have in mind no particular moment in the narrative. William Dorrit, Amy's father, known as "The Father of the Marshalsea" because he has been incarcerated in that debtors' prison for so many years — twenty-five, in fact — is an amiable but utterly impractical middle-aged gentleman whom Dickens based in part upon his own father, John Dickens. Like the elder Dickens, William Dorrit is providentially released from the debtors' prison by an inheritance, although the Dorrit windfall is considerably larger than that which John Dickens received. Amy, William's youngest child, born in the prison, has acquired the nickname "Little Dorrit." At the time that the story opens, the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger.

Little Dorrit and her Father

Sol Eytinge Jr.

"Little Dorrit and Her Father, Diamond edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1871)

Commentary:

The dual character study is different from others in Eytinge's Diamond Edition sequences of sixteen for each volume in that it post-dates Eytinge's 1869 visit to London and Gadshill. As is typical of these studies, Eytinge appears to have in mind no particular moment in the narrative. William Dorrit, Amy's father, known as "The Father of the Marshalsea" because he has been incarcerated in that debtors' prison for so many years — twenty-five, in fact — is an amiable but utterly impractical middle-aged gentleman whom Dickens based in part upon his own father, John Dickens. Like the elder Dickens, William Dorrit is providentially released from the debtors' prison by an inheritance, although the Dorrit windfall is considerably larger than that which John Dickens received. Amy, William's youngest child, born in the prison, has acquired the nickname "Little Dorrit." At the time that the story opens, the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger.

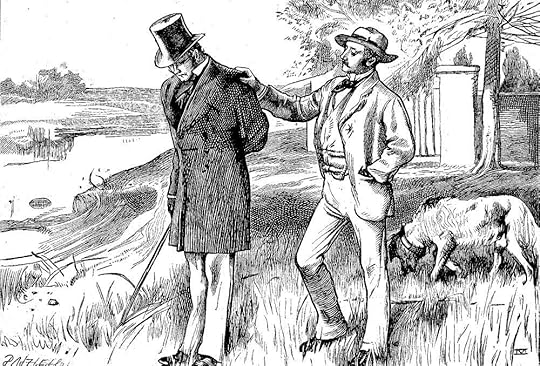

"What a good fellow you are, Clennam!"

Chaptr 34, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

Said Henry Gowan, the dilettante, socialite-artist and Minnie's fiané] . . . .Between you and me, I think there is some danger of my being just enough soured not to be able to do that."

"To do what?" asked Clennam.

"To keep it up. To help myself in my turn, as the man before me helps himself in his, and pass the bottle of smoke. To keep up the pretence as to labour, and study, and patience, and being devoted to my art, and giving up many solitary days to it, and abandoning many pleasures for it, and living in it, and all the rest of it — in short, to pass the bottle of smoke according to rule."

"But it is well for a man to respect his own vocation, whatever it is; and to think himself bound to uphold it, and to claim for it the respect it deserves; is it not?" Arthur reasoned. "And your vocation, Gowan, may really demand this suit and service. I confess I should have thought that all Art did."

"What a good fellow you are, Clennam!" exclaimed the other, stopping to look at him, as if with irrepressible admiration. "What a capital fellow! You have never been disappointed. That's easy to see."

It would have been so cruel if he had meant it, that Clennam firmly resolved to believe he did not mean it. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 34.

Commentary:

The title is somewhat longer in the New York (Harper and Brothers) printing: "What a good fellow you are, Clennam!" exclaimed the other stopping to look at him, as if with irrepressible admiration. "What a capital fellow! You have never been disappointed. That's easy to see." — Book 1, chap. xxxiv. In the original serial illustrations by Phiz provided, the previous chapter had an engraving which illustrated Mrs. Gowan's seeking the counsel of Mrs. Merdle about her son's forthcoming marriage to the daughter of a rich bourgeois, Mr. Meagles — "Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage" (Part 10: September 1856). Instead, Mahoney shows Arthur's apparent despondency occasioned by the marriage and Henry Gowan's lack of perceptiveness as to what is responsible for his friend's depression. Henry Gowan protests that in his profession and in his art he is a disappointed man, and that, although his father-in-law will pay all his debts, he does not feel one whit less disappointed even as his wedding approaches. Nevertheless, in the illustration he seems serene and cheerful when placed alongside Arthur Clennam, who had thought to marry Pet Meagles himself, and who has grave doubts about Henry's being the right sort of man for her. The illustration is interestingly juxtaposed against the text of Chapter 33, when Henry's mother in her visit to Mrs. Merdle expresses her intention, despite the discrepancy socially between the class of the bride and the class of the groom, to "resign herself to inevitable fate, by making the best of those people the Miggleses". Henry exhibits here what Dickens terms "his usual ease, and with his usual show of confidence, which was no confidence at all". Does Henry, Clennam wonders silently, have the capacity to love anyone but himself? The full title of the illustration, therefore, underscores the irony of Henry's failing to see that Arthur Clennam is the genuinely disappointed man, and that he, Henry Gowan, is a mere poser.

In Mahoney's illustration, set near the Cottage within a week of the wedding, Arthur Clennam is still wearing the same respectable, dark business suit (with tail-coat) and top-hat seen in his parting from Minnie (Pet Meagles), Minnie was there, alone (Ch. 28), whereas prospective bridegroom Henry Gowan in white from head to foot is much more fashionably bohemian (as becomes his status as an artist) in clothing quite different from his rather more formal attire as seen in "As Arthur Came over the stile and down to the water's edge, the lounger glanced at him for a moment" (Ch. 17), although Henry is still attended by his dog and the setting is still the banks of the Thames at Twickenham in the summer, as depicted in several of Phiz's atmospheric landscapes, notably the scene in which Gowan and Clennam first meet, "The Ferry" (Part 5: April 1856).

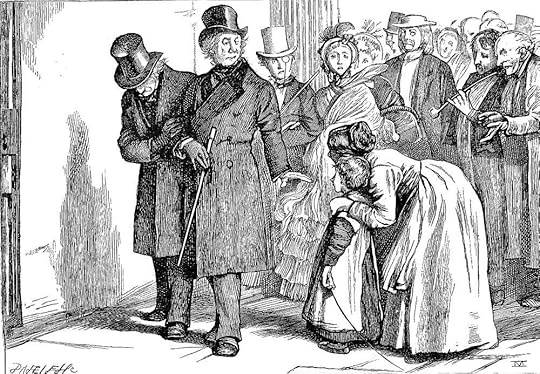

Clennam rose softly, opened and closed the door without a sound.

Chapter 35, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

The prison, which could spoil so many things, had tainted Little Dorrit's mind no more than this. Engendered as the confusion was, in compassion for the poor prisoner, her father, it was the first speck Clennam had ever seen, it was the last speck Clennam ever saw, of the prison atmosphere upon her.

He thought this, and forbore to say another word. With the thought, her purity and goodness came before him in their brightest light. The little spot made them the more beautiful.

Worn out with her own emotions, and yielding to the silence of the room, her hand slowly slackened and failed in its fanning movement, and her head dropped down on the pillow at her father's side. Clennam rose softly, opened and closed the door without a sound, and passed from the prison, carrying the quiet with him into the turbulent streets. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 35, "What Was Behind Mr. Pancks on Little Dorrit's Hand".

Commentary:

In the original serial illustrations by Phiz, the narrative-pictorial sequence moves directly from the discussion of the forthcoming wedding of Henry Gowan and Pet Meagles in the previous chapter's steel-engraving, "Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage" (Part 10: September 1856), to the final illustration of Book the First, Poverty, the triumphal exit of the Dorrit clan from the debtors' prison, "The Marshalsea becomes an orphan" (Part 10: September 1856). This mid-point serial installment ended with the architect of the Dorrit renaissance, Arthur Clennam, standing in the street outside the Marshalsea as he watches the entourage drive off.

Instead, Mahoney shows an intermediate scene in which, having delivered the good news, Arthur Clennam sensitively leaves the daughter to cope with her father's shock at the news of his release and sudden fortune, a scene which Felix Octavius Carr Darley tenderly realised in one of his engraved title-pages for the 1863 Household Edition produced as a piracy in New York, Joyful Tidings — Book I, Ch. XXXV, a study that Mahoney is not likely to have seen.

In James Mahoney's low-key illustration (the penultimate for the first book), set near the mid-point of the four-hundred-and-twenty-three-page volume, discretely the messenger of glad tidings, Arthur Clennam, with his hat on and ready to enter "the turbulent streets" which are about to receive the long-consigned William Dorrit, is caught in the act of closing the door to William Dorrit's bedroom. On the narrow bed with large pillows, the Father of the Marshalsea, still wearing his clothes and velvet skullcap, and his dutiful daughter are now both asleep, their faces betraying neither agitation nor doubt as to the veracity of Clennam's announcement.

The engaged reader, awaiting this climax in the Dorrit fortunes, scrutinizes the illustration proleptically, encountering the moment realised in the text some seven pages later, already having read that Pancks has resolved Mr. Dorrit's case and that "He will be a rich man. He is a rich man. A great sum of money is waiting to be paid over to him as his inheritance" (chapter 35). Such a windfall, although not entirely unexpected, effected the release of John Dickens from the Marshalsea after his incarceration for non-payment of tradesmen's accounts of forty pounds in 1824 for a mere three months that must have seemed like an eternity to his son, working at the blacking factory, the twelve-year-old Charles, whose purgatorial class descent is partly reflected in the tribulations of the sensitive and dutiful Amy Dorrit, faithful guardian of her father in in repose.

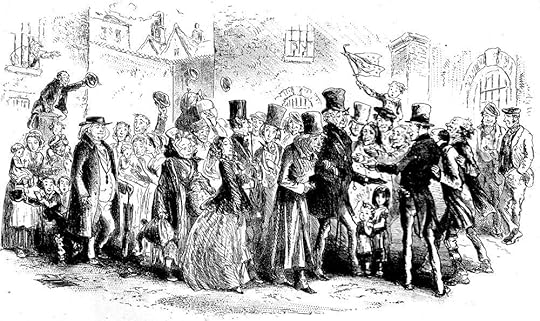

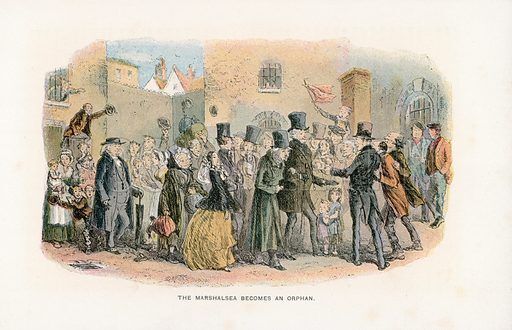

The Marshalsea becomes an orphan

Chapter 36, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"In the yard, were the Collegians and turnkeys. In the yard, were Mr Pancks and Mr Rugg, come to see the last touch given to their work. In the yard, was Young John making a new epitaph for himself, on the occasion of his dying of a broken heart. In the yard, was the Patriarchal Casby, looking so tremendously benevolent that many enthusiastic Collegians grasped him fervently by the hand, and the wives and female relatives of many more Collegians kissed his hand, nothing doubting that he had done it all. In the yard, was the man with the shadowy grievance respecting the Fund which the Marshal embezzled, who had got up at five in the morning to complete the copying of a perfectly unintelligible history of that transaction, which he had committed to Mr Dorrit's care, as a document of the last importance, calculated to stun the Government and effect the Marshal's downfall. In the yard, was the insolvent whose utmost energies were always set on getting into debt, who broke into prison with as much pains as other men have broken out of it, and who was always being cleared and complimented; while the insolvent at his elbow—a mere little, sniveling, striving tradesman, half dead of anxious efforts to keep out of debt—found it a hard matter, indeed, to get a Commissioner to release him with much reproof and reproach. In the yard, was the man of many children and many burdens, whose failure astonished everybody; in the yard, was the man of no children and large resources, whose failure astonished nobody. There, were the people who were always going out to-morrow, and always putting it off; there, were the people who had come in yesterday, and who were much more jealous and resentful of this freak of fortune than the seasoned birds. There, were some who, in pure meanness of spirit, cringed and bowed before the enriched Collegian and his family; there, were others who did so really because their eyes, accustomed to the gloom of their imprisonment and poverty, could not support the light of such bright sunshine. There, were many whose shillings had gone into his pocket to buy him meat and drink; but none who were now obtrusively Hail fellow well met! with him, on the strength of that assistance. It was rather to be remarked of the caged birds, that they were a little shy of the bird about to be so grandly free, and that they had a tendency to withdraw themselves towards the bars, and seem a little fluttered as he passed.

Through these spectators the little procession, headed by the two brothers, moved slowly to the gate. Mr Dorrit, yielding to the vast speculation how the poor creatures were to get on without him, was great, and sad, but not absorbed. He patted children on the head like Sir Roger de Coverley going to church, he spoke to people in the background by their Christian names, he condescended to all present, and seemed for their consolation to walk encircled by the legend in golden characters, 'Be comforted, my people! Bear it!'

At last three honest cheers announced that he had passed the gate, and that the Marshalsea was an orphan."

Through these spectators, the little procession, headed by the two brothers, moved slowly to the gate.

Chapter 36, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

In the yard, were the Collegians and turnkeys. In the yard, were Mr. Pancks and Mr. Rugg, come to see the last touch given to their work. In the yard, was Young John making a new epitaph for himself, on the occasion of his dying of a broken heart. In the yard, was the Patriarchal Casby, looking so tremendously benevolent that many enthusiastic Collegians grasped him fervently by the hand, and the wives and female relatives of many more Collegians kissed his hand, nothing doubting that he had done it all. In the yard, was the man with the shadowy grievance respecting the Fund which the Marshal embezzled, who had got up at five in the morning to complete the copying of a perfectly unintelligible history of that transaction, which he had committed to Mr. Dorrit's care, as a document of the last importance, calculated to stun the Government and effect the Marshal's downfall. In the yard, was the insolvent whose utmost energies were always set on getting into debt, who broke into prison with as much pains as other men have broken out of it, and who was always being cleared and complimented; while the insolvent at his elbow--a mere little, snivelling, striving tradesman, half dead of anxious efforts to keep out of debt--found it a hard matter, indeed, to get a Commissioner to release him with much reproof and reproach. In the yard, was the man of many children and many burdens, whose failure astonished everybody; in the yard, was the man of no children and large resources, whose failure astonished nobody. There, were the people who were always going out to-morrow, and always putting it off; there, were the people who had come in yesterday, and who were much more jealous and resentful of this freak of fortune than the seasoned birds. There, were some who, in pure meanness of spirit, cringed and bowed before the enriched Collegian and his family; there, were others who did so really because their eyes, accustomed to the gloom of their imprisonment and poverty, could not support the light of such bright sunshine. There, were many whose shillings had gone into his pocket to buy him meat and drink; but none who were now obtrusively Hail fellow well met! with him, on the strength of that assistance. It was rather to be remarked of the caged birds, that they were a little shy of the bird about to be so grandly free, and that they had a tendency to withdraw themselves towards the bars, and seem a little fluttered as he passed.

Through these spectators the little procession, headed by the two brothers, moved slowly to the gate. Mr. Dorrit, yielding to the vast speculation how the poor creatures were to get on without him, was great, and sad, but not absorbed. He patted children on the head like Sir Roger de Coverley going to church, he spoke to people in the background by their Christian names, he condescended to all present, and seemed for their consolation to walk encircled by the legend in golden characters, "Be comforted, my people! Bear it!"

At last three honest cheers announced that he had passed the gate, and that the Marshalsea was an orphan. Before they had ceased to ring in the echoes of the prison walls, the family had got into their carriage, and the attendant had the steps in his hand. — Book The First, "Poverty," conclusion of Chapter 36, "The Marshalsea becomes an Orphan".

Commentary:

Having received news of their good fortune, as in Darley's 1863 engraving Joyful Tidings, the Dorrits make a grand exit from the Marshalsea yard attended by a host of "collegians," incarcerated debtors. Phiz also shows the brothers making an earlier circuit of the exercise yard (for Frederick is not a prisoner of the Marshalsea, and is unfamiliar with its precincts) in The Brothers, so that, in essence, Mahoney had two models from which to work.

Whereas Phiz had treated the moment as a crowd scene, with all the Dorrits except Amy surrounded by the Collegians, Mahoney focuses on the distinguished, tailored figure of William Dorrit in stylish topcoat and beaver, deigning to pat upon the head ("like Sir Roger de Coverly going to church" in the celebrated Addison and Steele Spectator No. 2 essay) a pinafore child presented to him by her mother for a blessing, as if Mr. Dorrit were a visiting dignitary — or Christ in the leper colony. With his brother Frederick on his arm, apparently reluctant to be an active participant in the farewell procession, the Father of the Marshalsea at the hour of noon appointed for the family's departure by carriage leads the party composed of a monocled Edward ('Tip') and the vain Fanny. Again, as in Phiz's panoramic treatment, Amy is nowhere to be seen, for she has fainted in her room from all the excitement. In the Mahoney illustration one receives no impression of the scene's context (the prison yard), and Plornish and Maggy are absent. Although the dilapidated prison was closed in 1842 and subsequently demolished, Phiz and Dickens would have had little trouble reconstructing from memory the walled yard overlooked by barred windows, James Mahoney, although born in 1810, had moved to London only in 1859, and therefore had little sense of what the prison yard must have looked like in the period when John Dickens was incarcerated there. Thus, Mahoney concentrates on William Dorrit's apotheosis rather than on the crowd and the architectural setting.

Tristram wrote: "Julie wrote: "since a Dickens hero can fall in love (if that's what it is) repeatedly, but a heroine only once."

Tristram wrote: "Julie wrote: "since a Dickens hero can fall in love (if that's what it is) repeatedly, but a heroine only once."Like Peter, I really love this sentence and find that there is a lot of truth in it..."

How do we know that Arthur did not fund the search for the Dorrit wealth? I assumed he did. Pancks certainly was not rich. And it must have been an expensive search since it took so long.

Or did the Dorrits never even look for the money? I am still with Arthur here, he finally got to sit beside Amy and held her hand. peace, janz

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Although I was bored spending the entire chapter with the Barnacles, Mr. Meagles wasn't, at least he was cheered up by the thought of them being there."

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Although I was bored spending the entire chapter with the Barnacles, Mr. Meagles wasn't, at least he was cheered up by the thought of them being there."I skimmed the Barnacles section..."

I find that the Barnacles improve dramatically with a very sarcastic reader to over enunciate them, but I know I would also be skimming them otherwise.

I do think that Mr. Meagles got just one to many puppy dog eye treatments from Pet. That is the only answer that makes sense, unless further machinations are a work. Which does seem plausible at this point.