Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist - Group Read 5

>

Oliver Twist: Chapters 35 - 43

message 2:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 11, 2023 04:16AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

XVI – July 1838 - chapters 35–37

XVII – August 1838 - chapters 38–part of 39

XVIII – October 1838 - conclusion of chapter 39–41

XIX – November 1838 - chapters 42–43

LINKS TO CHAPTERS:

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39 (beginning)

Chapter 39 (end)

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

XVII – August 1838 - chapters 38–part of 39

XVIII – October 1838 - conclusion of chapter 39–41

XIX – November 1838 - chapters 42–43

LINKS TO CHAPTERS:

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39 (beginning)

Chapter 39 (end)

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

message 3:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 25, 2023 05:49AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Installment 16

Chapter 35:

Oliver cries out for help, and the household comes running. Oliver points in the direction Fagin took, and Harry Maylie runs off to find him, followed by Oliver, Mr. Giles, and Mr. Losberne. But despite their speed and thoroughness, they search in vain:

“There were not even the traces of recent footsteps, to be seen. They stood now, on the summit of a little hill, commanding the open fields in every direction for three or four miles.”

Harry Maylie says to Oliver that it must have been a dream, but Oliver insists:

“Oh no, indeed, sir,” … shuddering at the very recollection of the old wretch’s countenance; “I saw him too plainly for that. I saw them both, as plainly as I see you now.”

“Who was the other?” inquired Harry and Mr. Losberne, together.

“The very same man I told you of, who came so suddenly upon me at the inn,” said Oliver. “We had our eyes fixed full upon each other; and I could swear to him.”

Because of his earnest face, everyone believes Oliver.

Yet the long grass has no indentation, and is not trampled down in any direction, and there are no prints in the clay of the ditches. There isn’t the slightest mark to show that any feet had been there:

“This is strange!” said Harry.

“Strange?” echoed the doctor. “Blathers and Duff, themselves, could make nothing of it.”

Mr. Giles goes to the all the ale-houses in the village, and describes the pair, but nobody has seen them. All the next day they search again, but after a few days they begin to forget about it.

Meanwhile Rose continues to improve, and although everyone is much more cheerful, there is something ominous in the air. She and Mrs. Maylie are often “closeted together for long periods of time; and more than once Rose appears with traces of tears upon her face.”

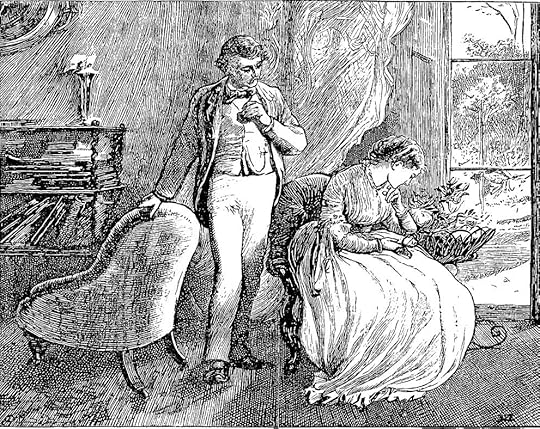

One morning, Harry Maylie finds Rose alone in the morning room and pours out his heart to her:

"A few — a very few — will suffice, Rose,"said the young man, drawing his chair towards her" - James Mahoney 1871

However, as Mrs. Maylie had foretold, Rose turns down Harry’s marriage proposal because she does not want her low beginnings to damage his prospects in life. Despite his pleading, she says that Harry “must endeavour to forget her and move beyond her and progress through the world”. When Harry persists, she admits:

“Then, if your lot had been differently cast … if you had been even a little, but not so far, above me; if I could have been a help and comfort to you in any humble scene of peace and retirement, and not a blot and drawback in ambitious and distinguished crowds … I own I should have been happier.”

Rose admits that she loves him and Harry says that he will ask her once more in a year’s time, even though she has said with a melancholy smile that “it will be useless.”

Chapter 35:

Oliver cries out for help, and the household comes running. Oliver points in the direction Fagin took, and Harry Maylie runs off to find him, followed by Oliver, Mr. Giles, and Mr. Losberne. But despite their speed and thoroughness, they search in vain:

“There were not even the traces of recent footsteps, to be seen. They stood now, on the summit of a little hill, commanding the open fields in every direction for three or four miles.”

Harry Maylie says to Oliver that it must have been a dream, but Oliver insists:

“Oh no, indeed, sir,” … shuddering at the very recollection of the old wretch’s countenance; “I saw him too plainly for that. I saw them both, as plainly as I see you now.”

“Who was the other?” inquired Harry and Mr. Losberne, together.

“The very same man I told you of, who came so suddenly upon me at the inn,” said Oliver. “We had our eyes fixed full upon each other; and I could swear to him.”

Because of his earnest face, everyone believes Oliver.

Yet the long grass has no indentation, and is not trampled down in any direction, and there are no prints in the clay of the ditches. There isn’t the slightest mark to show that any feet had been there:

“This is strange!” said Harry.

“Strange?” echoed the doctor. “Blathers and Duff, themselves, could make nothing of it.”

Mr. Giles goes to the all the ale-houses in the village, and describes the pair, but nobody has seen them. All the next day they search again, but after a few days they begin to forget about it.

Meanwhile Rose continues to improve, and although everyone is much more cheerful, there is something ominous in the air. She and Mrs. Maylie are often “closeted together for long periods of time; and more than once Rose appears with traces of tears upon her face.”

One morning, Harry Maylie finds Rose alone in the morning room and pours out his heart to her:

"A few — a very few — will suffice, Rose,"said the young man, drawing his chair towards her" - James Mahoney 1871

However, as Mrs. Maylie had foretold, Rose turns down Harry’s marriage proposal because she does not want her low beginnings to damage his prospects in life. Despite his pleading, she says that Harry “must endeavour to forget her and move beyond her and progress through the world”. When Harry persists, she admits:

“Then, if your lot had been differently cast … if you had been even a little, but not so far, above me; if I could have been a help and comfort to you in any humble scene of peace and retirement, and not a blot and drawback in ambitious and distinguished crowds … I own I should have been happier.”

Rose admits that she loves him and Harry says that he will ask her once more in a year’s time, even though she has said with a melancholy smile that “it will be useless.”

message 4:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 25, 2023 03:30PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Once again we have a chapter with two main themes. There is Harry and Rose’s unrequited passion, which surely must be a hanging thread, and hopefully something may change for them. These episodes are some of Charles Dickens's most melodramatic, and the Victorian audiences loved them.

But what Charles Dickens calls in his title the “unsatisfactory result of Oliver’s adventure” is extraordinary! We need to remember two things.

1. The instantaneous vanishing. Fagin and Monks seem to have literally disappeared into thin air. Fagin is hardly nimble, and Oliver jumped out of the window, yet they had already disappeared. The level of detail provided here seems to disprove that anyone could have physically been outside the window at all - or hidden either, with the intent to remove themselves later - since nobody in the area had seen the couple. Charles Dickens has made absolutely sure that his readers could not question this.

2. However Oliver said it was not a dream, and talked of things he could not have known. Charles Dickens also specified the illustration by George Cruikshank in great detail. At this time, if it had not happened, the episode would not be illustrated in this way. It would be an extension of an unreliable narrator, and readers would consider this most unfair!

How can we reconcile these opposing "truths" which Charles Dickens has presented us with here? Well Charles Dickens might say this ending is “unsatisfactory” but in fact it is very carefully described, and Charles Dickens knew exactly what he was doing.

Before looking further into what appears to be Oliver’s waking dream, it might be worth knowing some of the historical context. Note first, that chapter 35 was published in July 1838.

But what Charles Dickens calls in his title the “unsatisfactory result of Oliver’s adventure” is extraordinary! We need to remember two things.

1. The instantaneous vanishing. Fagin and Monks seem to have literally disappeared into thin air. Fagin is hardly nimble, and Oliver jumped out of the window, yet they had already disappeared. The level of detail provided here seems to disprove that anyone could have physically been outside the window at all - or hidden either, with the intent to remove themselves later - since nobody in the area had seen the couple. Charles Dickens has made absolutely sure that his readers could not question this.

2. However Oliver said it was not a dream, and talked of things he could not have known. Charles Dickens also specified the illustration by George Cruikshank in great detail. At this time, if it had not happened, the episode would not be illustrated in this way. It would be an extension of an unreliable narrator, and readers would consider this most unfair!

How can we reconcile these opposing "truths" which Charles Dickens has presented us with here? Well Charles Dickens might say this ending is “unsatisfactory” but in fact it is very carefully described, and Charles Dickens knew exactly what he was doing.

Before looking further into what appears to be Oliver’s waking dream, it might be worth knowing some of the historical context. Note first, that chapter 35 was published in July 1838.

message 5:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 01:45AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Dickens and Mesmerism

We have had several instances of Dreams and Visions already, and this one is perhaps the most baffling of all. However, when we remember that Charles Dickens was fascinated by mesmerism at the time, it all falls into place.

Oliver Twist was written between 1837 and 1839, at the height of “The Mesmeric Mania” in London, and Charles Dickens was a close friend of the doctor who was at its forefront in England, Dr. John Elliotson, who experimented with “animal magnetism”. The two were to remain staunch friends all their lives, with Charles Dickens dying just two years later than his friend. After Charles Dickens's own death, it was discovered that his huge library contained 14 well-thumbed volumes on mesmerism including one personally inscribed to him by John Elliotson.

John Elliotson was an outspoken senior physician, and Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine at the University of London. He worked out of the new University College Hospital (now a leading London Hospital) and his demonstrations of the “mighty curative powers of animal magnetism” (or therapeutic effects of mesmerism) on patients with nervous conditions, and those we now know to be suffering from epilepsy, were astonishing. By 1849, John Elliotson was also performing surgical operations without chloroform (or the more recently intoduced ether; introduced in 1847, but still before modern anaesthesia). He used mesmerism to relax the patient and keep them free from pain. In 1838 however this was still in the future.

The first demonstration we can be sure Charles Dickens attended was in January 1838, (at the time of installment 10, when Oliver is being prepared for the burglary at Chertsey) although he was well aware of this fascinating new area of study before, and had written about “magnetism” in his Sketches by Boz. Charles Dickens's letters show that he was regularly to view such demonstrations, despite the enormous pressure of his writing and editing work.

In addition, sometimes he and George Cruikshank would be personally invited to attend a private treatment, with a small group of up to half a dozen viewers. Other leading figures of the day, also attended: from the medical and scientific and literary world and including the writers Robert Browning, the historian John Forster, the great actor and Charles Dickens’s friend William Macready and others all attended the lectures/demonstrations. William Makepeace Thackeray and Alfred, Lord Tennyson (whom Goodreads calls Alfred Tennyson) were also greatly interested in mesmerism.

The demonstrations were reported in the medical professional magazine “The Lancet”; a weekly magazine created by Thomas Wakley in 1823, to deter charlatans, and disseminate the best original medical research. “The Lancet” remains the world’s leading general medical journal. This was cutting edge research for sure, but it was in its early stages, and as with so many other theories, some aspects now seem bizarre.

I’ll go into this a little more, for those interested.

We have had several instances of Dreams and Visions already, and this one is perhaps the most baffling of all. However, when we remember that Charles Dickens was fascinated by mesmerism at the time, it all falls into place.

Oliver Twist was written between 1837 and 1839, at the height of “The Mesmeric Mania” in London, and Charles Dickens was a close friend of the doctor who was at its forefront in England, Dr. John Elliotson, who experimented with “animal magnetism”. The two were to remain staunch friends all their lives, with Charles Dickens dying just two years later than his friend. After Charles Dickens's own death, it was discovered that his huge library contained 14 well-thumbed volumes on mesmerism including one personally inscribed to him by John Elliotson.

John Elliotson was an outspoken senior physician, and Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine at the University of London. He worked out of the new University College Hospital (now a leading London Hospital) and his demonstrations of the “mighty curative powers of animal magnetism” (or therapeutic effects of mesmerism) on patients with nervous conditions, and those we now know to be suffering from epilepsy, were astonishing. By 1849, John Elliotson was also performing surgical operations without chloroform (or the more recently intoduced ether; introduced in 1847, but still before modern anaesthesia). He used mesmerism to relax the patient and keep them free from pain. In 1838 however this was still in the future.

The first demonstration we can be sure Charles Dickens attended was in January 1838, (at the time of installment 10, when Oliver is being prepared for the burglary at Chertsey) although he was well aware of this fascinating new area of study before, and had written about “magnetism” in his Sketches by Boz. Charles Dickens's letters show that he was regularly to view such demonstrations, despite the enormous pressure of his writing and editing work.

In addition, sometimes he and George Cruikshank would be personally invited to attend a private treatment, with a small group of up to half a dozen viewers. Other leading figures of the day, also attended: from the medical and scientific and literary world and including the writers Robert Browning, the historian John Forster, the great actor and Charles Dickens’s friend William Macready and others all attended the lectures/demonstrations. William Makepeace Thackeray and Alfred, Lord Tennyson (whom Goodreads calls Alfred Tennyson) were also greatly interested in mesmerism.

The demonstrations were reported in the medical professional magazine “The Lancet”; a weekly magazine created by Thomas Wakley in 1823, to deter charlatans, and disseminate the best original medical research. “The Lancet” remains the world’s leading general medical journal. This was cutting edge research for sure, but it was in its early stages, and as with so many other theories, some aspects now seem bizarre.

I’ll go into this a little more, for those interested.

message 6:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Dec 12, 2024 04:28AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And a little more …

About the early theories of Animal Magnetism

John Elliotson’s basic two principles in 1838 were that:

1. Mechanical laws working in an alterate ebb and flow, “control a mutual influence between the Heavenly bodies, the Earth and animate bodies which exists as a universally distributed and continuous fluid … of a rarified nature.”

2. Since all the properties of matter depend on this operation, its influence or force could be communicated to animate or inanimate bodies. It was therefore possible he believed, to create a new theory about the nature of influence and power relationships between people, and also between people and the objects in their environment. If such were proved to be true, then he said “the art of healing will reach its final stage of perfection”.

Magnets were thought to be especially good conductors of the force or influence, so to distinguish it from mineral magnetism, he called it “animal magnetism. It became known as Mesmerism after the doctor who conceptualised this first, in the 18th century: the Viennese doctor Mesmer. Interestingly, it was a small circle of wealthy Jewish merchants who first paid for the private publication of an 1822 text by the German M. Loewe, which originally sparked interest in London.

As well as his interest in animal magnetism John Elliotson also funded and became the first president of the London Phrenological society in 1824, and this is where some of the managers of the hospital began to have reservations about his theories. Earlier Charles Dickens himself had poked fun at phrenology in one of his Sketches by Boz “Our Parish”. From around 1842 the supporters of “Phreno-magnetism” or “Phrenomesmerism” were divided from the more scientific investigations; the transcendentalists versus the mesmeric scientists, and various factions began to be set up, some with a more spiritual view of reality. John Elliotson’s reputation as a scientist was solidly secure in 1837, but mesmerism was deeply suspect.

Charles Dickens now developed an abiding belief in phrenology. Ten years later, in 1847 he refused to admit one woman as an inmate to his reformatory at Urania Cottage, on the grounds of her phrenology, stating that: “she had a singularly bad head, and looked discouragingly secret and moody”. And in 1868, receiving news of his friend John Elliotson’s death, he said: ”I hold phrenology, within certain limits to be true.”

John Elliotson became interested in the phenomenons of sleepwaking (waking dreams) and mesmeric trance, but was aware of the deceptions practised by others. One thorny issue was that of clairvoyance, which was ridiculed by most of the medical establishment. John Elliotson perfomed several tests with his regular patients to test this hypothesis.

Charles Dickens remained a staunch friend and believer. When “The Lancet” began to turn against mesmerism, Charles Dickens wrote with great anger:

“When I think that every rotten-hearted pander who has been beaten, kicked and rolled in the kennel yet struts it in the Editorial We once a week - every vagabond that a man’s gorge must rise at - every live emetic in that nauseous drugshop the Press - can have his fling at such men [Elliotson] and call them knaves and fools and thieves, I grow so vicious that with bearing hard upon my pen, I break the nib down and with keeping my teeth set, make my jaw ache.”

Phew! At 25 Charles Dickens was a very angry young man indeed!

However the terminology was changing, along with the discoveries. Seventy years after the concept had first been suggested, it was established that there was no invisible all-pervasive fluid or force. Any metaphorical language was abandoned, but mesmeric effects were agreed to be effective. The observed results were seen to be due to powerful imaginations working in congruence; mental forces not separate from the mind. What the mesmeric operator did to their subject had a new name. It was called “hypnosis”, and it was seen that “hypnosis” could indeed play an important role as a curative agent.

Charles Dickens himself practised mesmerism both as entertainment and therapeutically. His first subject was his wife Catherine. He also helped his friend and illustrator John Leech (the illustrator of A Christmas Carol) after a bad fall. Some of his “patients” were notable figures. I’ve written a little more about that here:

LINK HERE.

And LlNK HERE

for a post which relates it more to current science (there are tiny spoilers for Oliver Twist here. If you'd like to read how it relates to that novel, then have a look at the 4 post from #6 onwards in Chapters 35 - 43.

There is a wealth of information in Dickens and Mesmerism: The Hidden Springs of Fiction by the Dickens scholar Fred Kaplan, both about the history and theory of mesmerism, as well as detailed descriptions of the experiments and patients involved, gleaned from The Lancet.

About the early theories of Animal Magnetism

John Elliotson’s basic two principles in 1838 were that:

1. Mechanical laws working in an alterate ebb and flow, “control a mutual influence between the Heavenly bodies, the Earth and animate bodies which exists as a universally distributed and continuous fluid … of a rarified nature.”

2. Since all the properties of matter depend on this operation, its influence or force could be communicated to animate or inanimate bodies. It was therefore possible he believed, to create a new theory about the nature of influence and power relationships between people, and also between people and the objects in their environment. If such were proved to be true, then he said “the art of healing will reach its final stage of perfection”.

Magnets were thought to be especially good conductors of the force or influence, so to distinguish it from mineral magnetism, he called it “animal magnetism. It became known as Mesmerism after the doctor who conceptualised this first, in the 18th century: the Viennese doctor Mesmer. Interestingly, it was a small circle of wealthy Jewish merchants who first paid for the private publication of an 1822 text by the German M. Loewe, which originally sparked interest in London.

As well as his interest in animal magnetism John Elliotson also funded and became the first president of the London Phrenological society in 1824, and this is where some of the managers of the hospital began to have reservations about his theories. Earlier Charles Dickens himself had poked fun at phrenology in one of his Sketches by Boz “Our Parish”. From around 1842 the supporters of “Phreno-magnetism” or “Phrenomesmerism” were divided from the more scientific investigations; the transcendentalists versus the mesmeric scientists, and various factions began to be set up, some with a more spiritual view of reality. John Elliotson’s reputation as a scientist was solidly secure in 1837, but mesmerism was deeply suspect.

Charles Dickens now developed an abiding belief in phrenology. Ten years later, in 1847 he refused to admit one woman as an inmate to his reformatory at Urania Cottage, on the grounds of her phrenology, stating that: “she had a singularly bad head, and looked discouragingly secret and moody”. And in 1868, receiving news of his friend John Elliotson’s death, he said: ”I hold phrenology, within certain limits to be true.”

John Elliotson became interested in the phenomenons of sleepwaking (waking dreams) and mesmeric trance, but was aware of the deceptions practised by others. One thorny issue was that of clairvoyance, which was ridiculed by most of the medical establishment. John Elliotson perfomed several tests with his regular patients to test this hypothesis.

Charles Dickens remained a staunch friend and believer. When “The Lancet” began to turn against mesmerism, Charles Dickens wrote with great anger:

“When I think that every rotten-hearted pander who has been beaten, kicked and rolled in the kennel yet struts it in the Editorial We once a week - every vagabond that a man’s gorge must rise at - every live emetic in that nauseous drugshop the Press - can have his fling at such men [Elliotson] and call them knaves and fools and thieves, I grow so vicious that with bearing hard upon my pen, I break the nib down and with keeping my teeth set, make my jaw ache.”

Phew! At 25 Charles Dickens was a very angry young man indeed!

However the terminology was changing, along with the discoveries. Seventy years after the concept had first been suggested, it was established that there was no invisible all-pervasive fluid or force. Any metaphorical language was abandoned, but mesmeric effects were agreed to be effective. The observed results were seen to be due to powerful imaginations working in congruence; mental forces not separate from the mind. What the mesmeric operator did to their subject had a new name. It was called “hypnosis”, and it was seen that “hypnosis” could indeed play an important role as a curative agent.

Charles Dickens himself practised mesmerism both as entertainment and therapeutically. His first subject was his wife Catherine. He also helped his friend and illustrator John Leech (the illustrator of A Christmas Carol) after a bad fall. Some of his “patients” were notable figures. I’ve written a little more about that here:

LINK HERE.

And LlNK HERE

for a post which relates it more to current science (there are tiny spoilers for Oliver Twist here. If you'd like to read how it relates to that novel, then have a look at the 4 post from #6 onwards in Chapters 35 - 43.

There is a wealth of information in Dickens and Mesmerism: The Hidden Springs of Fiction by the Dickens scholar Fred Kaplan, both about the history and theory of mesmerism, as well as detailed descriptions of the experiments and patients involved, gleaned from The Lancet.

message 7:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 01:12PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Dreams and Visions - Mesmerism in Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist is peppered with mesmeric references, which sometimes come across as estoeric or spiritual. Sometimes it seems as if it is part of his allegory, such as when Oliver has the long journey between leaving Mr. Sowerberry’s and arriving with the Artful Dodger at Fagin’s lair. He calls to see Dick at Mrs. Mann’s baby farm, yet we know that the baby farm is a mere 3 miles from the workhouse. None of the geography makes sense, so we think ah, this is an allegorical journey, not a literal one.

But if we think of it from a mesmeric point of view, then the poignant episode between Oliver and Dick could have been a trance, or what the mesmerists call “sleepwaking”. Ditto the episode when Oliver watched Fagin and his treasures. And now, in chapter 34, we have the most irrefutable evidence of this “sleepwaking”. Oliver does not know the stranger (Monks), neither does he know of any connection between this man Monks and Fagin, plus none of what he says can make any sense to Oliver. But just as in Fagin’s lair (when he was fingering his treasures and talking to himself) Oliver hears every word. Dickens explains it for us in the text itself:

(These quotations are under spoilers merely because they are so long! No spoilers here!)

“There is a kind of sleep that steals upon us sometimes, which, while it holds the body prisoner, does not free the mind from a sense of things about it, and enable it to ramble at its pleasure. (view spoiler)

This is a description of a mesmeric trance, and it is followed by a description of how Oliver knew exactly where he was, but also felt he was back in Fagin’s lair. The conversation was thus heard by Oliver visiting them, in a mesmeric trance, involving clairvoyance.

“It was but an instant, a glance, a flash, before his eyes; and they were gone. But they had recognised him, and he them”

The recognition is also pertinent. Eyes, or staring, or a strong irresistible gaze are mentioned numerous times in Oliver Twist. We should also note that Monks suffers from fits, as did most of John Elliotson’s patients (and the practitioners of mesmerism themselves were also said to sometimes writhe and foam at the mouth).

Just to remind you of one more passage, this time from near the beginning of chapter 9:

“There is a drowsy state, between sleeping and waking, when you dream more in five minutes with your eyes half open, and yourself half conscious of everything that is passing around you, than you would in five nights with your eyes fast closed, (view spoiler)

Other psychological theories are that the personification of evil is always there to threaten Oliver. Examples include the hunch-backed man, which I went into earlier, but is unresolved, or the looming dread of Fagin. Oliver is continually locked up or hidden away, and is subject to beatings: “They’ll never do anything with him without stripes and bruises” says the gentleman in the white waistcoat, who is on the board of the workhouse. We are intended to draw parallels here. Goodness is hidden away, and lashes and blows were part of the sufferings of Christ.

Oliver Twist is peppered with mesmeric references, which sometimes come across as estoeric or spiritual. Sometimes it seems as if it is part of his allegory, such as when Oliver has the long journey between leaving Mr. Sowerberry’s and arriving with the Artful Dodger at Fagin’s lair. He calls to see Dick at Mrs. Mann’s baby farm, yet we know that the baby farm is a mere 3 miles from the workhouse. None of the geography makes sense, so we think ah, this is an allegorical journey, not a literal one.

But if we think of it from a mesmeric point of view, then the poignant episode between Oliver and Dick could have been a trance, or what the mesmerists call “sleepwaking”. Ditto the episode when Oliver watched Fagin and his treasures. And now, in chapter 34, we have the most irrefutable evidence of this “sleepwaking”. Oliver does not know the stranger (Monks), neither does he know of any connection between this man Monks and Fagin, plus none of what he says can make any sense to Oliver. But just as in Fagin’s lair (when he was fingering his treasures and talking to himself) Oliver hears every word. Dickens explains it for us in the text itself:

(These quotations are under spoilers merely because they are so long! No spoilers here!)

“There is a kind of sleep that steals upon us sometimes, which, while it holds the body prisoner, does not free the mind from a sense of things about it, and enable it to ramble at its pleasure. (view spoiler)

This is a description of a mesmeric trance, and it is followed by a description of how Oliver knew exactly where he was, but also felt he was back in Fagin’s lair. The conversation was thus heard by Oliver visiting them, in a mesmeric trance, involving clairvoyance.

“It was but an instant, a glance, a flash, before his eyes; and they were gone. But they had recognised him, and he them”

The recognition is also pertinent. Eyes, or staring, or a strong irresistible gaze are mentioned numerous times in Oliver Twist. We should also note that Monks suffers from fits, as did most of John Elliotson’s patients (and the practitioners of mesmerism themselves were also said to sometimes writhe and foam at the mouth).

Just to remind you of one more passage, this time from near the beginning of chapter 9:

“There is a drowsy state, between sleeping and waking, when you dream more in five minutes with your eyes half open, and yourself half conscious of everything that is passing around you, than you would in five nights with your eyes fast closed, (view spoiler)

Other psychological theories are that the personification of evil is always there to threaten Oliver. Examples include the hunch-backed man, which I went into earlier, but is unresolved, or the looming dread of Fagin. Oliver is continually locked up or hidden away, and is subject to beatings: “They’ll never do anything with him without stripes and bruises” says the gentleman in the white waistcoat, who is on the board of the workhouse. We are intended to draw parallels here. Goodness is hidden away, and lashes and blows were part of the sufferings of Christ.

message 8:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 01:14PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

If you feel rather cynical about all of this, then console yourself with the thought that Charles Dickens still had not planned the novel in detail. When he was discussing the stage productions of Oliver Twist (see my earlier post) Charles Dickens was still considering writing these himself, but in the end did not. In the middle of March 1838, just a couple of months before this, he had written to Frederick Yates: “I am satisfied that nobody can have heard what I mean to to with the different characters, inasmuch as I don’t quite know myself.”

However, he had promised to get each impending installment to George Cruikshank by the 5th of the preceding month. Sometimes he did not manage this, and gave his instructions by word of mouth. So if you prefer to ignore all Charles Dickens’s philosophical musings, you can console yourself with this thought …

He had not actually written the description of Fagin and Monks’s presence at the window, and their overheard converation, followed by the detailed and incontrovertible description of how they must have disappeared into thin air, when George Cruikshank was busily etching his illustration. (And all the other illustrations of course came after.) So it’s quite possible that at the time Charles Dickens had in his mind that Fagin and Monks would be caught in the act, when Oliver roused the household.

However, he had promised to get each impending installment to George Cruikshank by the 5th of the preceding month. Sometimes he did not manage this, and gave his instructions by word of mouth. So if you prefer to ignore all Charles Dickens’s philosophical musings, you can console yourself with this thought …

He had not actually written the description of Fagin and Monks’s presence at the window, and their overheard converation, followed by the detailed and incontrovertible description of how they must have disappeared into thin air, when George Cruikshank was busily etching his illustration. (And all the other illustrations of course came after.) So it’s quite possible that at the time Charles Dickens had in his mind that Fagin and Monks would be caught in the act, when Oliver roused the household.

message 9:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 25, 2023 12:40PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Bionic Jean wrote: "Any thoughts about Harry Maylie, or Rose?"

Bionic Jean wrote: "Any thoughts about Harry Maylie, or Rose?"I believed based on the information Dickens has provided, Harry Maylie is a politician. We learn earlier Mr. Maylie was residing at the home of a great personage. There is mention he has not achieved his goals. Given he is five and twenty we could rule out a profession like law where he would be old enough to start his career. Then Miss Maylie states this:

"All the honors to which great talents and powerful connexions can help men in public life, are in store for you".

Then as Ms. Bionic posted, Rose admits she would marry Harry if his profession was not one where Rose's dubious birth would not hurt his prospects. One wonders what Harry was thinking when he proposed. He must be well aware he would have no political career if he married Rose. But he appears unwilling to give up that career for a different profession. He seems to be trying to have his cake and eat it too,

Perhaps it is true in all times, but especially during this time a young politician needed a powerful patron. A patron could be in effective control of Parliamentary seats he can hand to one to his clients. This practice was curtailed as a large number of the rotten boroughs were eliminated with the Grear Reform Act of 1832 but power brokers could still yield direct influence on who was elected to parliament. Elections were and are costly affairs so a patron would be required to pay the necessary bribes, gifts, and drinks to the electors; this is prior to secret ballots. Another factor what we would call political parties were in a nascent stage. Thirdly a member of Parliament was not paid so one needed to be independently well off or have a patron cover costs.

Mrs. Maylie is a married name so was Rose's mother the sister of Harry's father?

Bionic Jean wrote: " These episodes are some of Charles Dickens's most melodramatic, and the Victorian audiences loved them."

Bionic Jean wrote: " These episodes are some of Charles Dickens's most melodramatic, and the Victorian audiences loved them."To be totally honest, I enjoy scenes as we just experienced with Harry and Rose. It is one of the reasons I read Victorian literature. Such scenes produce some of the most memorable passages and images in English Literature.

First, having the extra day to catch up was very helpful to me--thanks!

First, having the extra day to catch up was very helpful to me--thanks!The proposal scene made me think of Laurie and Jo in Little Women, the way he says he worked so hard for her, and his refusal to accept her answer as final. I know it's not an uncommon plot, but I still wondered if this story might have been in the back of Alcott's mind.

And I was thinking how different our reactions reading today might be to the Victorian audiences, who as you say, Jean, loved the melodrama. I don't feel very invested in the love story, since we just met these characters, but the original audiences had been thinking of Rose for a long time, and were surely very invested in her!

The mesmerism details are fascinating, Jean. I look forward to us batting this around more as we go ...

Kathleen wrote: "The proposal scene made me think of Laurie and Jo in Little Women, the way he says he worked so hard for her, and his refusal to accept her answer as final. I know it's not an uncommon plot, but I still wondered if this story might have been in the back of Alcott's mind."

Kathleen wrote: "The proposal scene made me think of Laurie and Jo in Little Women, the way he says he worked so hard for her, and his refusal to accept her answer as final. I know it's not an uncommon plot, but I still wondered if this story might have been in the back of Alcott's mind."Alcott definitely read Dickens' work, and liked it. (The March sisters, whom Alcott modeled on herself and her own siblings, are into The Pickwick Papers, and role-play members of the Pickwick Club; that in itself tells us something!) Literary influence by Dickens on aspects of her work is certainly a viable possibility.

As far as the melodramatic aspects here, I'm of the school that distinguishes between lousy, eye-rolling melodrama, vs. good, well-written melodrama. Dickens produces the latter kind. :-)

Very interesting about the mesmerism, Jean. I certainly never would have considered that as an explanation for what happened. Still a strange one though I don’t have any better!

Very interesting about the mesmerism, Jean. I certainly never would have considered that as an explanation for what happened. Still a strange one though I don’t have any better!

message 16:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 03:35AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Michael said "Mrs. Maylie is a married name so was Rose's mother the sister of Harry's father?"

Well of course we do not know at this point, but it's an interesting possibility and very Dickensian! On the other hand, all we do know are Rose's own words (when pleading with her aunt for mercy when Oliver was captured after the aborted burglary) from chapter 30:

"as you love me, and know that I have never felt the want of parents in your goodness and affection, but that I might have done so, and might have been equally helpless and unprotected with this poor child"

However, since Mrs. Maylie seem to be quite wealthy, it seems a bit extreme of Rose to imply she would be in the same desperate state that Oliver is in! We have to assume I think that Rose was an unwanted orphan.

Well of course we do not know at this point, but it's an interesting possibility and very Dickensian! On the other hand, all we do know are Rose's own words (when pleading with her aunt for mercy when Oliver was captured after the aborted burglary) from chapter 30:

"as you love me, and know that I have never felt the want of parents in your goodness and affection, but that I might have done so, and might have been equally helpless and unprotected with this poor child"

However, since Mrs. Maylie seem to be quite wealthy, it seems a bit extreme of Rose to imply she would be in the same desperate state that Oliver is in! We have to assume I think that Rose was an unwanted orphan.

message 17:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 03:46AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Katheen and Sue - I'm so pleased you enjoyed all the research I did on mesmerism and about how it relates to Charles Dickens! It took absolutely ages ... but this makes it worthwhile 😊

message 18:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 03:49AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Well spotted Kathleen (and Werner) about the influences and parallels between The Pickwick Papers and Little Women. I think another reader said at one time that Jo was reading a novel by Charles Dickens, possibly A Tale of Two Cities?

Here's an interesting feature detailing all the the allusions: (WARNING! It does contain lots of spoilers about Little Women though.)

https://lw150.wordpress.com/tag/charl...

Apparently The Louisa May Alcott Encyclopedia: says that Charles Dickens was one of Louisa May Alcott’s “early literary idols”. (As he should be! 😁)

Here's an interesting feature detailing all the the allusions: (WARNING! It does contain lots of spoilers about Little Women though.)

https://lw150.wordpress.com/tag/charl...

Apparently The Louisa May Alcott Encyclopedia: says that Charles Dickens was one of Louisa May Alcott’s “early literary idols”. (As he should be! 😁)

message 19:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 03:54AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Chapter 36:

“is a very short one, and may appear of no great importance in its place, but it should be read notwithstanding, as a sequel to the last, and a key to one that will follow when its time arrives.”

Oliver has breakfast with Dr. Losberne and Harry Maylie, who are preparing to leave for home. The doctor is surprised at Harry’s sudden change of mind about staying for a while. After his talk with Rose, Harry is in a hurry to leave the Maylies’ house, and Dr. Losberne asks if: “any communication from the great nobs [has] produced this sudden anxiety on your part to be gone”. Harry says has has not heard from his uncle or any other “great nobs”, quoting Dr. Losberne, but he does not tell the doctor the real reason for his leaving.

The two men continue to discuss Harry’s career prospects. He is likely to become a member of parliament before the end of the year, and the doctor assumes that this is the reason Harry is heading back to London.

Before he leaves Harry asks Oliver if his writing is coming on well, and when Oliver confirms that is it, Harry Maylie ask him to write him a letter twice a month, with news of of his aunt and Rose. However he asks Oliver to keep this secret, so as not to worry his aunt. Oliver is delighted to be able to help in any way he can.

So Dr. Losberne waits in the post-chaise, (a small horse-drawn carriage that holds two passengers), while:

“Harry cast one slight glance at the latticed window, and jumped into the carriage.

“Drive on!” he cried, “hard, fast, full gallop! Nothing short of flying will keep pace with me, to-day.””

And as the carriage departs at full speed, unseen behind the white curtain which shrouds her from view, Rose weeps as she watches the carriage take them away.

Keira Knightley as Rose Maylie in the 1999 miniseries by Alan Bleasdale

“is a very short one, and may appear of no great importance in its place, but it should be read notwithstanding, as a sequel to the last, and a key to one that will follow when its time arrives.”

Oliver has breakfast with Dr. Losberne and Harry Maylie, who are preparing to leave for home. The doctor is surprised at Harry’s sudden change of mind about staying for a while. After his talk with Rose, Harry is in a hurry to leave the Maylies’ house, and Dr. Losberne asks if: “any communication from the great nobs [has] produced this sudden anxiety on your part to be gone”. Harry says has has not heard from his uncle or any other “great nobs”, quoting Dr. Losberne, but he does not tell the doctor the real reason for his leaving.

The two men continue to discuss Harry’s career prospects. He is likely to become a member of parliament before the end of the year, and the doctor assumes that this is the reason Harry is heading back to London.

Before he leaves Harry asks Oliver if his writing is coming on well, and when Oliver confirms that is it, Harry Maylie ask him to write him a letter twice a month, with news of of his aunt and Rose. However he asks Oliver to keep this secret, so as not to worry his aunt. Oliver is delighted to be able to help in any way he can.

So Dr. Losberne waits in the post-chaise, (a small horse-drawn carriage that holds two passengers), while:

“Harry cast one slight glance at the latticed window, and jumped into the carriage.

“Drive on!” he cried, “hard, fast, full gallop! Nothing short of flying will keep pace with me, to-day.””

And as the carriage departs at full speed, unseen behind the white curtain which shrouds her from view, Rose weeps as she watches the carriage take them away.

Keira Knightley as Rose Maylie in the 1999 miniseries by Alan Bleasdale

message 20:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 04:01AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Well this is a short chapter, and perhaps a relief after all the challenging ideas about reality. For fans of melodrama, this is a particularly poignant episode 😥

At the beginning of Chapter 36, Mr. Losberne says to Harry that “the great nobs … will get [him] into parliament at the election before Christmas”, so Michael was correct.

In Victorian England members of parliament did not receive a salary, so they had to be extremely rich to be able to afford to serve. Typically, a group of wealthy supporters, (or “nobs” as Dr. Losberne calls them) would sponsor the political career of a man who did not have the necessary means. But to retain their support, the candidate had to meet their criteria. For Harry, among other things, that meant having a wife who was above reproach.

Once again there is no illustration at all for this chapter, so although it does not match the action, I've included a photo still of Dr. Losberne and Rose, from one of the best miniseries dramtisations.

At the beginning of Chapter 36, Mr. Losberne says to Harry that “the great nobs … will get [him] into parliament at the election before Christmas”, so Michael was correct.

In Victorian England members of parliament did not receive a salary, so they had to be extremely rich to be able to afford to serve. Typically, a group of wealthy supporters, (or “nobs” as Dr. Losberne calls them) would sponsor the political career of a man who did not have the necessary means. But to retain their support, the candidate had to meet their criteria. For Harry, among other things, that meant having a wife who was above reproach.

Once again there is no illustration at all for this chapter, so although it does not match the action, I've included a photo still of Dr. Losberne and Rose, from one of the best miniseries dramtisations.

message 21:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 05:10AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Mr. Losberne and Harry Maylie leave in a post-chaise, a small carriage that held two passengers. It was called “post” because it was the only type of carriage besides a mail coach or stagecoach that could change its team of horses at various stages of its journey. This meant that the vehicle could keep travelling rather than stopping for the animals to feed and rest. While most middle-class travellers would use a mail coach or stagecoach, those with more money would travel in their own or a rented post-chaise.

Over to you!

Over to you!

Bionic Jean wrote: "Well spotted Kathleen (and Werner) about the influences and parallels between The Pickwick Papers and Little Women. I think another reader said at one time that Jo was rea..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Well spotted Kathleen (and Werner) about the influences and parallels between The Pickwick Papers and Little Women. I think another reader said at one time that Jo was rea..."Thank you so much for expanding on this, Jean and Werner! My multiple readings of Little Women happened before I read any Dickens, so missed all of the connections at that time, other than knowing their Pickwick Club was based on a Dickens novel. The article you linked to was so interesting to me, Jean!

This was a speedy chapter, kind of a transition. I always wondered about the post-chaise, Jean--I am learning so much here. :-)

Bionic Jean wrote: "It was called “post” because it was the only type of carriage besides a mail coach or stagecoach that could change its team of horses at various stages of its journey. This meant that the vehicle could keep travelling rather than stopping for the animals to feed and rest."

Bionic Jean wrote: "It was called “post” because it was the only type of carriage besides a mail coach or stagecoach that could change its team of horses at various stages of its journey. This meant that the vehicle could keep travelling rather than stopping for the animals to feed and rest."That's a fact I wasn't aware of; thanks, Jean! (I knew, from context, that post-chaises were light vehicles, but that's all I knew.)

I'm showing my ignorance here, but I'm hoping for some more clarification. I knew that mail and stage coaches could change their teams, because they were operated by large-scale enterprises that could own many horses, and keep teams of them in readiness at various stages along their routes. But wouldn't the cost and inconvenience of this be a problem for private parties who traveled only on occasion, even if they were rich or middle class? And if the owners (or renters) of post-chaises could do this, why couldn't those who used other types of vehicles?

message 24:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 26, 2023 11:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Werner wrote: "I'm hoping for some more clarification ..."

Here's wiki https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post_ch...

18th and 19th century English literature is full of phaetons, post-chaises and postilions, but I think when the US adopted the name "post-chaise" it meant something a little different.

Here's wiki https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post_ch...

18th and 19th century English literature is full of phaetons, post-chaises and postilions, but I think when the US adopted the name "post-chaise" it meant something a little different.

The appearance of Fagin and Monks at the window seems especially mysterious because the two appear together. For Oliver to have dreamed of one or the other of them at his window would make sense based on the trauma each has given him, but for them to appear together when Oliver doesn't know that they are connected suggests that it is not a dream. Was Oliver somehow "in tune" with them, or did they really appear and then manage to disappear without a trace?

The appearance of Fagin and Monks at the window seems especially mysterious because the two appear together. For Oliver to have dreamed of one or the other of them at his window would make sense based on the trauma each has given him, but for them to appear together when Oliver doesn't know that they are connected suggests that it is not a dream. Was Oliver somehow "in tune" with them, or did they really appear and then manage to disappear without a trace?Either way, Oliver's credibility suffers another blow!

message 27:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 01:46AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Exactly Erich (see my message 7) ... and as I also said, none of what Monks says can make any sense to Oliver, just as none of what Fagin said in Oliver's waking dream in chapter 9 made any sense to him. Yet it is reported word for word.

However we try to rationalise this, Charles Dickens gives us no reasonable chance to do so!

However we try to rationalise this, Charles Dickens gives us no reasonable chance to do so!

message 28:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 01, 2023 07:16AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Chapter 37:

Back at the workhouse, Mr. Bumble has now been married to the former Mrs. Corney for two months, and things are not going well. Although he has been promoted to the master of the workhouse, he has not gained any prestige. Mr. Bumble is gloomy over the loss of his status as a beadle:

“Dignity, and even holiness too, sometimes, are more questions of coat and waistcoat than some people imagine … Another beadle had come into power. On him the cocked hat, gold-laced coat, and staff, had all three descended.”

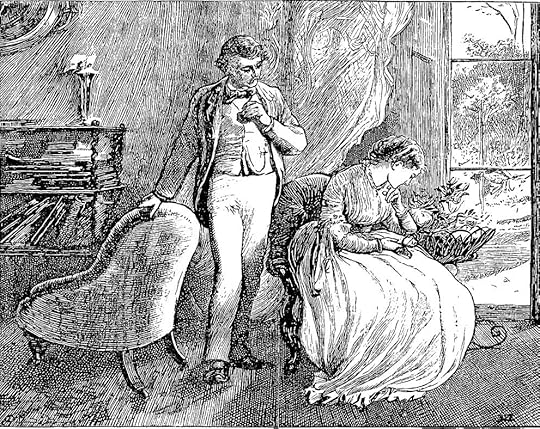

Mr. Bumble now believes that he sold himself for a few pieces of silver and second-hand furniture. He feels he has made a mistake in marrying Mrs. Corney. In the span of two months of married life, he has gone from being in charge, to being fully domesticated and entrapped in marriage. Mr. Bumble tries to assert his authority, and tells his wife that “the prerogative of a man is to command”. Mrs. Bumble responds by bursting into tears:

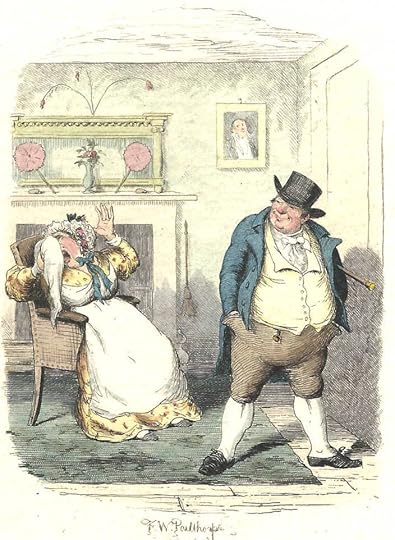

"Bumble triumphant" - Frederic W. Pailthorpe 1886

But finding that her tears do not have the desired effect, she attacks him with physical violence, clasping him tightly round the throat and inflicting a shower of blows upon his head:

“Mr. Bumble was fairly taken by surprise, and fairly beaten. He had a decided propensity for bullying: derived no inconsiderable pleasure from the exercise of petty cruelty; and, consequently, was (it is needless to say) a coward.”

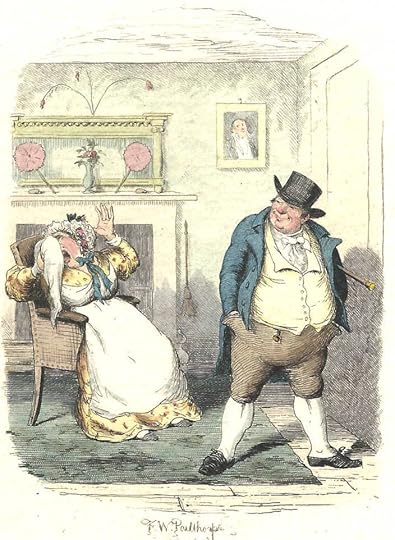

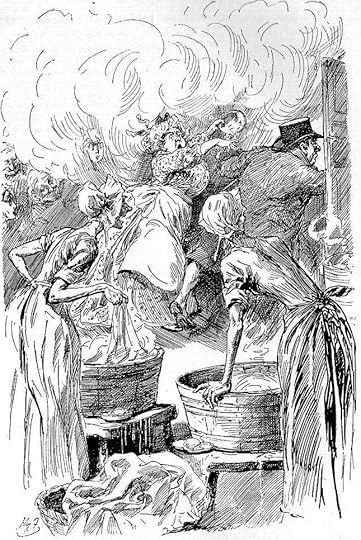

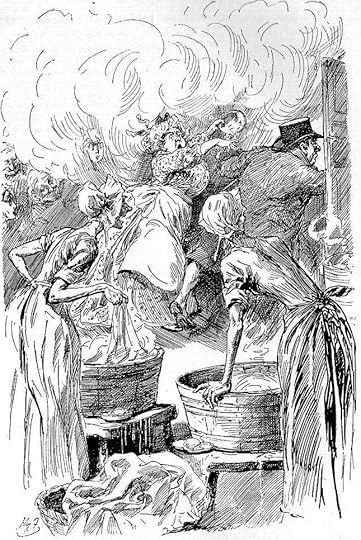

Even the paupers know Mr. Bumble’s wife rules the roost. When on his rounds he sees some female paupers washing the parish linen, and is surprised to see that his wife is with them. He is told by her that he is not to interfere, not to poke his nose where it does not belong, and that he “makes a fool of himself every hour of the day”.

"Mr. Bumble degraded in the eyes of the paupers" - George Cruikshank July 1838

"Mrs. Bumble turns Mr. Bumble out" - Harry Furniss 1910

As a result of this confrontation with his wife, Mr. Bumble now loses all respect even from the paupers:

“he had fallen from all the height and pomp of beadleship, to the lowest depth of the most snubbed hen-peckery”.

Feeling degraded, Mr. Bumble heads for a deserted tavern where there is only one other customer: a tall, dark an who is wearing a large cloak. This man appears dusty and looks as if he has travelled a long way. His face wears “a scowl of distrust and suspicion, unlike anything [Bumble] had observed before, and repulsive to behold”.

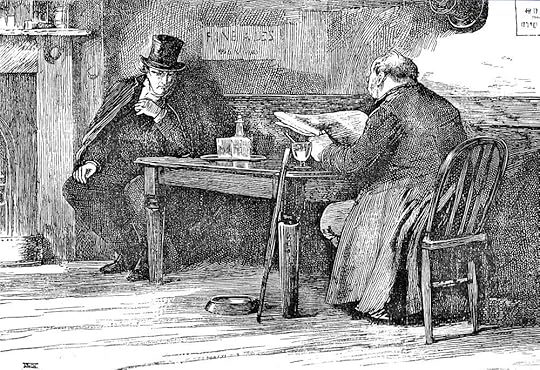

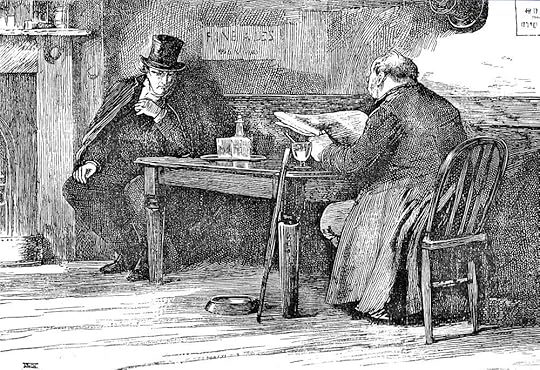

"Were you looking for me," he said, "when you peered in at the window?" James Mahoney 1871

An awkward conversation follows, in which Mr. Bumble confirms to the stranger in the cloak that he had once been the parochial beadle. The man then buys Mr. Bumble a drink, and says:

“Carry your memory back—let me see—twelve years, last winter.”

“It’s a long time,” said Mr. Bumble. “Very good. I’ve done it.”

“The scene, the workhouse.”

The stranger is looking for information about a woman who attended a particular birth at that time. The child was:

“a meek-looking, pale-faced boy, who was apprenticed down here, to a coffin-maker—I wish he had made his coffin, and screwed his body in it—and who afterwards ran away to London, as it was supposed.”

Mr. Bumble easily supplies the name “Oliver”, but the stranger knows enough of him. He wants to know about “the hag that nursed his mother”. Where is she? When told that she is dead, the cloaked man seems resigned, and gets up to leave. But Mr. Bumble quickly realises that his wife may know some secret. He remembers that Old Sally had nursed Oliver’s mother, and that something had happened the night of Old Sally’s death. Moreover he remembers that his wife (Mrs. Corney at that point) had been the solitary witness. He tells the stranger that “one woman had been closeted with the old harridan shortly before she died”, and as a consequence, the man in the cloak asks them both to meet him the following evening at 9 o’clock. He writes the address down on a scrap of paper and urges secrecy.

As he leaves, Mr. Bumble hurries after him, saying:

“What name am I to ask for?”

“Monks!” rejoined the man; and strode hastily away.”

This is the end of installment 16.

Back at the workhouse, Mr. Bumble has now been married to the former Mrs. Corney for two months, and things are not going well. Although he has been promoted to the master of the workhouse, he has not gained any prestige. Mr. Bumble is gloomy over the loss of his status as a beadle:

“Dignity, and even holiness too, sometimes, are more questions of coat and waistcoat than some people imagine … Another beadle had come into power. On him the cocked hat, gold-laced coat, and staff, had all three descended.”

Mr. Bumble now believes that he sold himself for a few pieces of silver and second-hand furniture. He feels he has made a mistake in marrying Mrs. Corney. In the span of two months of married life, he has gone from being in charge, to being fully domesticated and entrapped in marriage. Mr. Bumble tries to assert his authority, and tells his wife that “the prerogative of a man is to command”. Mrs. Bumble responds by bursting into tears:

"Bumble triumphant" - Frederic W. Pailthorpe 1886

But finding that her tears do not have the desired effect, she attacks him with physical violence, clasping him tightly round the throat and inflicting a shower of blows upon his head:

“Mr. Bumble was fairly taken by surprise, and fairly beaten. He had a decided propensity for bullying: derived no inconsiderable pleasure from the exercise of petty cruelty; and, consequently, was (it is needless to say) a coward.”

Even the paupers know Mr. Bumble’s wife rules the roost. When on his rounds he sees some female paupers washing the parish linen, and is surprised to see that his wife is with them. He is told by her that he is not to interfere, not to poke his nose where it does not belong, and that he “makes a fool of himself every hour of the day”.

"Mr. Bumble degraded in the eyes of the paupers" - George Cruikshank July 1838

"Mrs. Bumble turns Mr. Bumble out" - Harry Furniss 1910

As a result of this confrontation with his wife, Mr. Bumble now loses all respect even from the paupers:

“he had fallen from all the height and pomp of beadleship, to the lowest depth of the most snubbed hen-peckery”.

Feeling degraded, Mr. Bumble heads for a deserted tavern where there is only one other customer: a tall, dark an who is wearing a large cloak. This man appears dusty and looks as if he has travelled a long way. His face wears “a scowl of distrust and suspicion, unlike anything [Bumble] had observed before, and repulsive to behold”.

"Were you looking for me," he said, "when you peered in at the window?" James Mahoney 1871

An awkward conversation follows, in which Mr. Bumble confirms to the stranger in the cloak that he had once been the parochial beadle. The man then buys Mr. Bumble a drink, and says:

“Carry your memory back—let me see—twelve years, last winter.”

“It’s a long time,” said Mr. Bumble. “Very good. I’ve done it.”

“The scene, the workhouse.”

The stranger is looking for information about a woman who attended a particular birth at that time. The child was:

“a meek-looking, pale-faced boy, who was apprenticed down here, to a coffin-maker—I wish he had made his coffin, and screwed his body in it—and who afterwards ran away to London, as it was supposed.”

Mr. Bumble easily supplies the name “Oliver”, but the stranger knows enough of him. He wants to know about “the hag that nursed his mother”. Where is she? When told that she is dead, the cloaked man seems resigned, and gets up to leave. But Mr. Bumble quickly realises that his wife may know some secret. He remembers that Old Sally had nursed Oliver’s mother, and that something had happened the night of Old Sally’s death. Moreover he remembers that his wife (Mrs. Corney at that point) had been the solitary witness. He tells the stranger that “one woman had been closeted with the old harridan shortly before she died”, and as a consequence, the man in the cloak asks them both to meet him the following evening at 9 o’clock. He writes the address down on a scrap of paper and urges secrecy.

As he leaves, Mr. Bumble hurries after him, saying:

“What name am I to ask for?”

“Monks!” rejoined the man; and strode hastily away.”

This is the end of installment 16.

message 29:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 02:49AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And another cliffhanger! What does Monks have to do with anything?

I really like this longish chapter, right from the tongue-in-cheek title, with its comic relief. It seems a very long time since we have been in the workhouse, and we couldn’t have expected Mr. Bumble to have anything to do with Monks, although Monks seems to have been around on the periphery of various events for a while. Perhaps Charles Dickens is beginning to see a way to bring all these strands of his sketches about the "Parish Boy’s Progress" for Bentley’s miscellany together.

Mr. Bumble has always been a bully, (as Charles Dickens points out) and it is so satisfying to see him get his comeuppance, not only from his wife but also from the female paupers. I quite like the symbolism of him contemplating “a Paper fly-cage [which] dangled from the ceiling”. Just as the flies are trapped by the paper fly-cage, so Mr. Bumble feels confined and trapped by his marriage to Mrs. Corney. There are some great quotations in this part.

I really like this longish chapter, right from the tongue-in-cheek title, with its comic relief. It seems a very long time since we have been in the workhouse, and we couldn’t have expected Mr. Bumble to have anything to do with Monks, although Monks seems to have been around on the periphery of various events for a while. Perhaps Charles Dickens is beginning to see a way to bring all these strands of his sketches about the "Parish Boy’s Progress" for Bentley’s miscellany together.

Mr. Bumble has always been a bully, (as Charles Dickens points out) and it is so satisfying to see him get his comeuppance, not only from his wife but also from the female paupers. I quite like the symbolism of him contemplating “a Paper fly-cage [which] dangled from the ceiling”. Just as the flies are trapped by the paper fly-cage, so Mr. Bumble feels confined and trapped by his marriage to Mrs. Corney. There are some great quotations in this part.

message 30:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 04:18AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

But then the comedy is over, and we gradually switch tone as Mr. Bumble enters a public house and meets an unexpected (but familiar to us) character. Mr. Bumble is still the pompous Mr. Bumble, drinking his gin and water in silence, and reading his paper “with great pomp and circumstance” (this latter is from William Shakespeare’s Othello. Mr. Bumble attempts to keep up his show of authority during the conversation, but it is paper-thin. The stranger plies him with drink (a “jorum” is a large drinking bowl) and is clearly not short of money, giving him two gold sovereigns for information.

This second section is imbued with an air of menace, with the stranger cursing and wishing pestilence (“murrain”) should fall on the workhouse orphans. But it leaves us wanting more. I was interested to see that the final sentence confirms what we all suspected: i.e. that the stranger is Monks, because in later novels Charles Dickens would confidently expected that his descriptions had sufficed, and the character would have kept his apparent air of mystery, remaining “the stranger” or “the man in the cloak”.

This was to become one of Charles Dickens’s signature habits of style, and is one of the very small ways by which we can tell it is Charles Dickens's first proper novel.

This second section is imbued with an air of menace, with the stranger cursing and wishing pestilence (“murrain”) should fall on the workhouse orphans. But it leaves us wanting more. I was interested to see that the final sentence confirms what we all suspected: i.e. that the stranger is Monks, because in later novels Charles Dickens would confidently expected that his descriptions had sufficed, and the character would have kept his apparent air of mystery, remaining “the stranger” or “the man in the cloak”.

This was to become one of Charles Dickens’s signature habits of style, and is one of the very small ways by which we can tell it is Charles Dickens's first proper novel.

message 31:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 04:34AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Monks’s extensive knowledge about the nurse at Oliver’s birth, and about Mr. Bumble makes him seem an even greater threat, and deepens the mystery surrounding Oliver’s true identity. He must have gone to a lot of trouble to find all this out. But why is he so interested anyway?

We now have 2 days’ break and will begin installment 17 with chapter 38 on Friday. Plenty of time to catch up with any comments you missed, and share your theories and observations.

Let’s hear from some of our “silent observers” too! I’m reliably informed you’re there, so we’d love to hear your thoughts.

We now have 2 days’ break and will begin installment 17 with chapter 38 on Friday. Plenty of time to catch up with any comments you missed, and share your theories and observations.

Let’s hear from some of our “silent observers” too! I’m reliably informed you’re there, so we’d love to hear your thoughts.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Well this is a short chapter, and perhaps a relief after all the challenging ideas about reality. For fans of melodrama, this is a particularly poignant episode 😥

Bionic Jean wrote: "Well this is a short chapter, and perhaps a relief after all the challenging ideas about reality. For fans of melodrama, this is a particularly poignant episode 😥At the beginning of Chapter 36, M..."

I must admit I used the mention of a December election to try to date the novel. There was a general election in beginning of 1835 so that would place the novel in 1834; the same year as the Poor Law Amendment Act. More contemporaneous with the publishing date, there as an election in summer of 1837 due to Queen Victoria's ascension to the throne. 1837 was the last general election triggered by the death of the monarch as the law changed during Victoria's lifetime.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Chapter 37:

Bionic Jean wrote: "Chapter 37:When we first learn of Mr. Bumble's interest in Mrs. Corney the common reaction was the satiric, they deserve each other. Dickens delivered on that expectation. Dickens does not even bother with describing events that mark the point where each party became disillusioned with the other. Given the two characters involved, this marriage was destined to fail from the moment they signed the license.

This work is infused with what we classify as domestic violence.

One thing that stood out was Mr. Bumble did not physically retaliate. Should the reader give him some credit for that?

How does Mr. Bumble respond to his humiliation; he tries to find some workhouse residents to bully, only to have his wife degrade him even more.

Michael wrote: "How does Mr. Bumble respond to his humiliation; he tries to find some workhouse residents to bully, only to have his wife degrade him even more..."

Michael wrote: "How does Mr. Bumble respond to his humiliation; he tries to find some workhouse residents to bully, only to have his wife degrade him even more..."I think that was my favorite part of the chapter :-) Good job Mrs. Corney! Mr. Bumble is easy to dislike. It made me mad that he boxed the ears of the boy who opened the gate for him simply because he had been humiliated by his wife.

I've been away from the computer for a couple days but wanted to comment that I love all the information on mesmerism, thank you for that Jean. I'm really enjoying how Dickens is using mesmerism in this story. The fact that there is no rational explanation for the things Oliver says, well, it just makes the story fun to read. It keeps me wanting more.

I will also echo the sentiments about all the great info on mesmerism and how that could play into this story. The previous chapter with Harry & Rose was a little sugarplum and tenderness that was a nice addition, although I must admit I'm not sure of the reason for it. I hope Mr. Dickens will have something good come from it.

I will also echo the sentiments about all the great info on mesmerism and how that could play into this story. The previous chapter with Harry & Rose was a little sugarplum and tenderness that was a nice addition, although I must admit I'm not sure of the reason for it. I hope Mr. Dickens will have something good come from it.I thoroughly enjoyed the browbeating that Mr. Bumble received from his wife. It was nice to know that this self-satisfied bully is not the king of his castle and that his wife asserts herself when necessary! Quite a humorous scene!!

The black clouds are gathering for poor Oliver again it appears. Why this little orphan is so desired by such a variety of people both good and nefarious is what makes us so invested in him, don't you think? My heart is ready for him to be left alone in the company of those who would care for him and he, them. But I fear it is not to be....yet.

message 36:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 01:00PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Bridget wrote: "[I]wanted to comment that I love all the information on mesmerism, thank you for that Jean. I'm really enjoying how Dickens is using mesmerism in this story...."

Thanks Bridget and Chris - I did worry a little that I was bamboozling everyone - I nearly bamboozled myself! 😂 But it is fascinating to see these early theories of mesmerism that scientists were investigating - and realise properly what Charles Dickens was so enthusiastic about! We we can see more instances of it in Oliver Twist than in any other novel of his, although there are passages elsewhere too.

Thanks Bridget and Chris - I did worry a little that I was bamboozling everyone - I nearly bamboozled myself! 😂 But it is fascinating to see these early theories of mesmerism that scientists were investigating - and realise properly what Charles Dickens was so enthusiastic about! We we can see more instances of it in Oliver Twist than in any other novel of his, although there are passages elsewhere too.

message 37:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 01:05PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Michael - Yes, the novel was set on the cusp of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which Charles Dickens was very aware of, and reporting on daily in the "Morning Chronicle" at the time, before he left the newspaper (see my earlier post). So Oliver Twist is almost (but not exactly) contemporary. That's why Mr. Bumble talked earlier about the outdoor relief for the poor, which was being stopped.

Thanks for the historical perspective.

Thanks for the historical perspective.

Looking back a moment to Chapter 36, I've found Dickens' dialogue for Oliver a bit troubling: even though he has recently been studying diligently, speech patterns generally do not change quickly, even in children. His early education was surely minimal and his exposure almost entirely to workhouse people and the like. And yet, his speech in dealing with those in this household seems very polished and precise, with no hint of street jargon.

Looking back a moment to Chapter 36, I've found Dickens' dialogue for Oliver a bit troubling: even though he has recently been studying diligently, speech patterns generally do not change quickly, even in children. His early education was surely minimal and his exposure almost entirely to workhouse people and the like. And yet, his speech in dealing with those in this household seems very polished and precise, with no hint of street jargon.I find it less than realistic.

One other concern re Chapter 36: Harry has, in effect engaged Oliver as a spy in the Maylie household. While Harry's motivation is clear, his judgment is questionable. This might put Oliver in a very difficult position. He doesn't need another reason for people to mistrust him.

One other concern re Chapter 36: Harry has, in effect engaged Oliver as a spy in the Maylie household. While Harry's motivation is clear, his judgment is questionable. This might put Oliver in a very difficult position. He doesn't need another reason for people to mistrust him.

message 40:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 03:08PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Jim wrote: "his speech in dealing with those in this household seems very polished and precise, with no hint of street jargon. ..."

Yes, it is not at all realistic Jim - but to be fair - it never has been! Nor was it intended to be. Note Charles Dickens's own words from the Preface:

"I saw no reason, when I wrote this book, why the dregs of life (so long as their speech did not offend the ear) should not serve the purpose of a moral, as well as its froth and cream ..."

(We'll read the preface afterwards, because Charles Dickens assumed that his readers were already familiar with the story from the serial.)

Oliver has always talked like a polite middle class child, with his "Please Sir" in the workhouse, his "If you please sir" to the merry old gentleman Fagin, and his "Indeed Sir!" now. Even when Oliver inhabited a realistic East London slum world peopled by criminals, he was set apart from and above it.

His speech is such that a middle class audience relates to him. The readers of 1837 would have no empathy - nor would they understand - a child who uttered a series of vowels and unintelligible cockney criminal slang. Even the speech of Bill Sikes and the other villains is carefully presented to us - it is not actually how they would have talked. Charles Dickens did not want to alienate or offend his readers, as he said.

The other aspect of course is that Oliver is an ideal of innocence.

Yes, it is not at all realistic Jim - but to be fair - it never has been! Nor was it intended to be. Note Charles Dickens's own words from the Preface:

"I saw no reason, when I wrote this book, why the dregs of life (so long as their speech did not offend the ear) should not serve the purpose of a moral, as well as its froth and cream ..."

(We'll read the preface afterwards, because Charles Dickens assumed that his readers were already familiar with the story from the serial.)

Oliver has always talked like a polite middle class child, with his "Please Sir" in the workhouse, his "If you please sir" to the merry old gentleman Fagin, and his "Indeed Sir!" now. Even when Oliver inhabited a realistic East London slum world peopled by criminals, he was set apart from and above it.

His speech is such that a middle class audience relates to him. The readers of 1837 would have no empathy - nor would they understand - a child who uttered a series of vowels and unintelligible cockney criminal slang. Even the speech of Bill Sikes and the other villains is carefully presented to us - it is not actually how they would have talked. Charles Dickens did not want to alienate or offend his readers, as he said.

The other aspect of course is that Oliver is an ideal of innocence.

message 41:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 27, 2023 03:30PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Jim wrote: "While Harry's motivation is clear, his judgment is questionable. This might put Oliver in a very difficult position..."

Excellent point!

There have been several times already when Oliver's story seems frankly incredible. Examples include at Mr. Brownlow's, when he tells a long unlikely story about a band of thieves - and even argues that his name is different from the "Tom White" the court had recorded. Or when he protested to the Maylies that he was forced to be part of the gang who tried to burgle their house ... and also with Dr. Losberne, when he identified a house as one he was kept in against his will, only to find a strange hunch-backed man living there, and the whole interior completely different from what he described.

Oliver has no proof for any of these, yet he is always believed because (we are told) he looks so earnest and innocent.

Excellent point!