Library of Congress's Blog

November 26, 2025

Four Years After Sondheim’s Death, Adam Guettel Remembers the Man Behind the Legend

—This is a guest post by Adam Guettel, the Tony Award-winning composer and lyricist of “The Light in the Piazza,” “Floyd Collins” and “Days of Wine and Roses.” It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which was primarily devoted to the arrival of Sondheim’s collection at the Library.

Stephen Sondheim died on November 26, 2021, relaxing into the arms of his husband, Jeff. What a triumph of a life, and what an exit.

The thing is, I hadn’t realized Steve was gone until just now. Maybe that’s because he’s not gone. He’s still here. And let me say right off, he wasn’t my mentor or advisor in a consistent way. His advice was sporadic, but indelible. I think I remember everything he ever said to me about music or writing for the theater.

One of Steve’s great inventions, among many, was his phrasing. He broke from the long, lyrical lines of Kern, Rodgers, Gershwin and Porter. He divided melody into conversational clauses, as Stravinsky divided folk melodies into cells in “L’Histoire du Soldat,” “Les Noces” and “Le Sacre du Printemps.”

Fifty years apart, they shocked and insulted music and theater conservatives in Europe and New York with the same profound insight: that melody could be pixelated and recombined into something original and dynamic. What a blessing that this migration can be charted in the Sondheim Collection and the rich collection of Stravinsky manuscripts in the Library.

And there is the Steve I knew as a person. (So much has been thoughtfully written about his work.) Many were intimidated by him. But for a man at the pinnacle of the arts, he was a social journeyman; rumpled, shy, easily embarrassed, warm, generous, easily offended and quick to forgive. Doing his best. People probably thought Beethoven was grouchy, too.

Once, I brought Steve to Wempe, an elegant watch boutique on 5th Avenue, thinking he might be drawn to a beautiful watch, where less was more, and content dictated form, and God was in the details. He politely turned them all down. On the way to lunch, he said he didn’t understand spending so much on something that did so little. Sort of like the opposite of clarity.

On my piano rests one of Steve’s planetary watches, an orrery. It’s made of metal, beautiful and precise. That’s his level of interest, way up there, his level of endeavor, and now he circles around us, a giant in the sky. He’ll always be a giant here, too, thanks to the Library of Congress. He will never be gone. We can know him, and ask him and have him forever.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 24, 2025

Send in the Genius: Stephen Sondheim

This article also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which is primarily devoted to Stephen Sondheim’s collection coming to the Library. The cover story contains more detail.

It was late in rehearsals for “A Little Night Music,” and Stephen Sondheim had yet to write the show’s penultimate song. The male lead was to sing it during a scene with an ex-lover, explaining why he couldn’t leave his still-virginal wife and rekindle his relationship with her. But director Hal Prince determined the song should instead be for her.

Sondheim attended a rehearsal of the scene, directed to reveal the change in focus. He was convinced. Afterward, Sondheim and Prince retired to a bar to discuss it; Sondheim took notes, then went home to write the first chorus. The next day, he played it for his collaborators and with their blessing completed the song that night — possibly the fastest Sondheim ever wrote a song.

By this time, he knew the show intimately and, more relevantly, the strengths and weaknesses of actress Glynis Johns, who would sing the new song. She had a light, silvery voice but couldn’t sustain long notes.

This led to a song of short phrases that suggested a series of questions: “Isn’t it rich? Are we a pair?” And because the character Johns played is an actress, the song included lines like “Making my entrance again with my usual flair/Sure of my lines.”

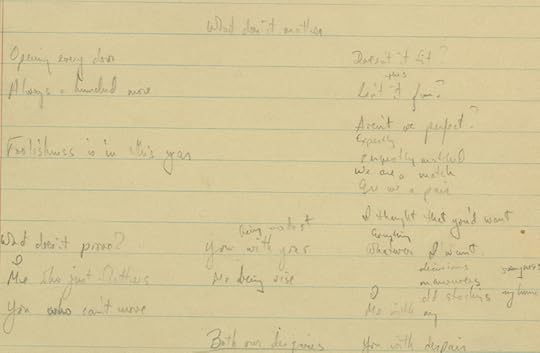

Sondheim sketched out an early draft of “Send in the Clowns” lyrics in longhand, trying different lines and words. The pattern of short questions is developing on the right hand side.

Sondheim sketched out an early draft of “Send in the Clowns” lyrics in longhand, trying different lines and words. The pattern of short questions is developing on the right hand side.“Send in the Clowns,” written in about 24 hours, ironically became Sondheim’s most famous and oft-recorded song, with well over 400 covers. Judy Collins’ recording of it won a Grammy, as did Sondheim for song of the year. Since then, it has been performed and recorded in almost every style imaginable (including a disco version by Grace Jones).

Because of the speed with which it was written, Sondheim made far fewer sketches for the song than for almost any other song. But what is there is deep and rich, including three dense pages comprising an interior monologue — the characters’ subtext — and two pages of monologue with the character expressing her reasons and arguments to him.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 20, 2025

The Secrets of Illustrating Bug Beauties in the 17th Century

—This is a guest post by Cindy Connelly Ryan, a preservation science specialist in the Preservation Research and Testing Division, and Jessica Fries-Gaither, an Albert Einstein distinguished educator fellow at the Library. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Would you raise insects in your kitchen? Travel thousands of miles from home to study them?

Maria Sibylla Merian, a 17th-century natural scientist, artist and engraver, did just that and broke new ground in science and art.Born in Germany in 1647 and later a resident of the Netherlands, Merian raised the larvae of caterpillars, butterflies and moths, determined their preferred food plants and observed adults emerging from their pupal chrysalides and cocoons. Her detailed notes and sketches became the basis for several groundbreaking books on caterpillars. She pioneered scientific illustration techniques by using counterproof printing to create softer images that more closely resembled her original drawings. She published De Europischen Insecten, and the Library preserves a copy of that book, now more than 300 years old.

In 1699, the intrepid Merian and her youngest daughter journeyed to the Dutch colony of Suriname in South America to study and paint insects. Back home, she published a book in 1705 — Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Metamorphosis of Surinamese Insects) — that featured vibrant color illustrations of exotic species.

Recent analysis by scientists in the Library’s Preservation Research and Testing Division revealed details about how the book’s colors were created. X-ray fluorescence provided elemental “fingerprints” of materials, and reflectance spectroscopy captured chemical bonds’ visible and near-infrared absorption features. Multiband microscopy revealed details of the paints’ textures, layering and application techniques.

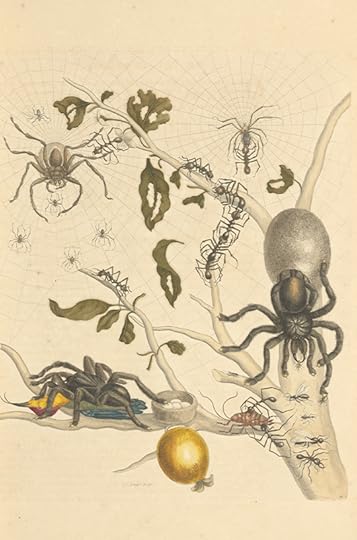

Merian’s artwork, here of spiders, gained her lasting fame. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Merian’s artwork, here of spiders, gained her lasting fame. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The red cherries are rendered with the poisonous pigment vermilion applied in matte and glossy layers to model depth. The caterpillar hungrily advancing up the branch is rendered in at least eight shades of yellow, gold, orange and red, all made from mixtures of just two pigments.

The colorants were created with a combina tion of European and imported raw materials. Butterflies get their blue colors from thin layers of azurite, a mineral mined in Hungary and Germany. Translucent pink and burgundy tones come from brazilwood, a South American tree first used by European artists in the early 1600s.

In this way, modern science sheds new light on centuries-old science and art.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 29, 2025

Broadway Comes to the Library, and the Library Goes to Broadway

This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a public affairs specialist in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In a page among the Library’s Jonathan Larson Papers, the visionary composer and playwright mused: “… if I want to try to cultivate a new audience for musicals I must write shows with a score that MTV ears will accept.”

Larson’s collection is not the largest in the Library’s Music Division, but among the roughly 15,000 items included within it are scripts, personal writings, programs, correspondence, recordings, lyric sheets and even floppy disks that provide an intimate look into the mind of a generational artist.

Larson, who also was a lyricist and performer, once wrote that “creating rock operas” was his “true calling.” Although he died tragically young in 1996 (he was 35 and was felled by a sudden aortic dissection), the contemporary themes and style of his works — modern, introspective, political — have continued to inspire creators and audiences alike.

“I am striving to become a writer and composer of musicals…” a page from one of Jonathan Larson’s notebooks. Music Division.

“I am striving to become a writer and composer of musicals…” a page from one of Jonathan Larson’s notebooks. Music Division. His most well-known musical, the Tony Award- and Pulitzer Prize-winning “Rent,” has been staged around the world and was adapted into a 2005 film featuring many of the original Broadway cast. But it is an earlier project — Larson’s semiautobiographical musical “tick, tick … Boom!” — that influenced the 2021 Lin-Manuel Miranda film of the same name.

As his collection demonstrates, Larson’s “tick, tick … Boom!” was constantly evolving. His papers feature numerous iterations and evolutions of the musical’s script, which began as a one-man rock monologue called “30/90.” Promotional materials show that Larson later staged the show under the title “Boho Days” before settling on its final name.

Miranda, who earned international acclaim for his groundbreaking musical “Hamilton,” played Larson in a 2014 revival of “tick, tick … Boom!” His movie fleshes out Larson’s story with insights from his papers and adds songs from the collection that did not appear in the composer’s original versions of the show.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Steven Levenson and Jennifer Ashley Tepper in the Library’s Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Steven Levenson and Jennifer Ashley Tepper in the Library’s Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.Miranda was joined by scriptwriter Steven Levenson and theater historian Jennifer Ashley Tepper in a 2017 visit to the Library as part of the research for the film.

Tepper’s experience with the Larson Papers is extensive. As the creator of “The Jonathan Larson Project,” which completed its off-Broadway run earlier this year, Tepper began her research with the collection nearly a decade ago. In days spent poring through his written materials and listening to hours of recordings of Larson performing his own songs, Tepper discovered notes, reflections and ideas that revealed the depth of the artist’s passion and vision.

Tepper called her experience with the Larson collection “the adventure of a theatre historian’s wildest dreams.”

“The Jonathan Larson Project” originally began as a concert of Larson’s music in 2018, transforming over the years into a full-scale stage musical. It features around 20 lesser-known Larson songs, including music never before performed as part of a show, songs cut from “tick, tick…Boom!” and “Rent” and songs from unproduced shows, like Larson’s musical adaptation of “1984” and an original sci-fi musical called “Superbia.”

Leonard Bernstein in his home studio in Fairfield, Connecticut, in 1988. Photo: Joe McNally. Prints and Photographs Division.

Leonard Bernstein in his home studio in Fairfield, Connecticut, in 1988. Photo: Joe McNally. Prints and Photographs Division. The expansive papers and manuscripts of another legendary Broadway figure, the renowned Leonard Bernstein, also were recently the subject of study for two films about the conductor-composer. Bernstein’s Broadway bona fides include “On the Town,” “Candide,” the short-lived “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” and the inimitable “West Side Story,” which itself received a modern film adaptation in 2021.

His more than 400,000-item Library collection includes materials not just from his professional life, but personal letters, recordings, scrapbooks, photographs and physical objects.

Bernstein is best recognized for his musical contributions, but his lifelong commitment to civil rights and work as a humanitarian were a major focus of Douglas Tirola’s 2021 documentary “Bernstein’s Wall.” The film weaves audio and images of the artist’s activism around societal issues — concerns about McCarthyism, civil rights and the war in Vietnam — with footage highlighting his personal life and musical genius.

Library staff helped the documentary team find and select images from the collection, including photos from Bernstein’s childhood and wedding — some of which appear in the finished film. Even more detail on this topic can be found in the Library’s collection, which holds materials documenting the many engagements and fundraising efforts Bernstein and his wife, Felicia Montealegre Bernstein, undertook for a range of causes.

The 2023 biographical drama “Maestro” from Bradley Cooper also drew many insights from the Library’s Bernstein Collection. The film’s team examined photos of Bernstein’s suits, a ring, his glasses and even re-created the musician’s “MAESTRO1” license plate for the movie. The Library has shared more about the “Maestro” team’s research process online and in the March/April 2024 issue of the Library’s magazine.

In cases like these, a line from the eighth Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam rings especially true: “A book used is fulfilling a higher purpose than a book which is merely preserved.” It remains a powerful mission to share the Library’s unparalleled collections so their stories can be interpreted through new voices and told to new generations (even if they don’t watch MTV anymore).

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 25, 2025

The Genius of Stephen Sondheim: Forever at the Library

—This is a guest post by Mark Eden Horowitz, a senior music specialist in the Music Division. It also appears in the September-October issue of the LIbrary of Congress Magazine.

When Stephen Sondheim first visited the Library of Congress in May 1993, the Music Division arranged for a private show of its treasures with the intention to knock his socks off. The subtext, of course, was to convince him that the Library would be the ideal home for his manuscripts.

At that time, Sondheim already was considered one of the most important figures in the history of musical theater. He was the lyricist behind “West Side Story”; the creator of “Company,” “Follies,” “A Little Night Music” and “Sweeney Todd”; the winner of a Pulitzer Prize, an Academy Award and multiple Grammys and Tonys; the man who, in receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom years later, would be credited with reinventing the American musical.

So we covered a small room with music manuscripts and other material from our collections: papers from his mentor, Oscar Hammerstein II, and collaborators Leonard Bernstein and Richard Rodgers; manuscripts by his private composition teacher, Milton Babbitt; works by composers and songwriters he admired, like Bartók, Berlin, Kern, Porter, Rachmaninov, Ravel.

We knew we’d succeeded when, looking at George Gershwin’s manuscript for “Porgy and Bess,” Sondheim began to cry. In a thank you letter, he wrote: “I’ve not stopped talking about what I saw at the Library since.”

Not long after, he agreed to leave his manuscripts to the Library in his will. Then, in February 1995, tragedy struck: a fire in Sondheim’s home in Manhattan. Though much was lost or damaged, the manuscripts miraculously were spared. Singe marks outlined where they sat in cardboard boxes on shelves — literally seconds from going up in flames. A collection of Sondheim music. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A collection of Sondheim music. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.The fire prompted Sondheim to make his first donation to the Library. That June, the Library received his vast record collection, approximately 15,000 LPs. Sondheim was an omnivorous collector of both classical and serious contemporary music recordings, many of them obscure, a surprising number of Scandinavian and South American composers. The collection was accompanied by his meticulously maintained (though also singed) hand-typed card catalog.

Over the years, Sondheim maintained connections to the Library.

He and collaborator John Weidman conducted research here, watching original films of vaudeville performers as they were writing their musical “Bounce.” He sat for a series of interviews — 6.5 hours’ worth are available on the Library’s website. He helped persuade friends and colleagues like Arthur Laurents and Hal Prince to also give their papers to the Library. In 2000, the Library celebrated Sondheim’s 70th birthday in the Coolidge Auditorium with a memorable concert that featured Broadway stars Nathan Lane, Audra McDonald, Marin Mazzie, Debra Monk and Brian Stokes Mitchell.

Now, more than 30 years after that first visit and four years after his death, the Sondheim collection has arrived at the Library and is accessible to researchers. It’s extraordinarily rich, with 5,000-plus items like music and lyric sketches and manuscripts in Sondheim’s clear, careful hand.

For the song “Putting It Together” from “Sunday in the Park with George” alone, there are five annotated script pages, 61 pages of lyric sketches, 18 pages of music sketches and an 80-page “fair copy” of the completed number — 164 pages for one song.

The Library’s Sondheim collection has much of his handwritten work, showing his creative process. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.

The Library’s Sondheim collection has much of his handwritten work, showing his creative process. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.The collection includes songs that were never used or were cut from shows or were written for shows that never materialized, such as a proposed film musical, “Singing Out Loud,” and “Muscle,” a one-act musical that originally would have been paired with “Passion.” There are three boxes of non-show songs, much of it specialty material such as birthday songs he wrote for friends like Bernstein and Prince.

Most thrilling, perhaps, is what Sondheim’s manuscripts reveal about the craft of composition, both music and lyrics. For Sondheim’s most famous song, “Send in the Clowns” from “A Little Night Music,” the first step appears to have been a one-page interior monologue discussing the character Desirée’s thoughts and feelings — her subtext.

It reads in part:

“We’re having a parallel experience — & I can’t convince you … I didn’t want to marry you. I’m getting what I deserve, but I didn’t kill anybody. Who did I hurt? Me. I want to right it all before it’s too late. Serves me right. I thought I wanted to rescue you — & myself. But how can you rescue someone who doesn’t want to be rescued? … How do you make somebody want something?”

It is dense and emotional stuff.

Stephen Sondheim at work in 1993. Photo: Nancy Lee Katz. Prints and Photographs Division.

Stephen Sondheim at work in 1993. Photo: Nancy Lee Katz. Prints and Photographs Division.There is “Not a Day Goes By” from “Merrily We Roll Along,” where it’s sung in two versions — as a torch song and a love song. As the lyric begins to coalesce in the sketches, we get to these lines where Sondheim has a partial lyric but also considers alternate possibilities (in the sketches, the words shown here in brackets are penciled above the words they follow):

“That I just can’t keep

Thinking + sweating and burning [shaking raging] + crying

And thinking [hurting] + reaching [hoping] and waking + dying.”

In addition to the above lines, in the left margin of this single page he lists more than a dozen alternate words to consider for the release: “trembling,” “circling,” “fiercer,” “rougher,” “viler.” Though verbs and adjectives are comingled here, one discovers in the final versions of the song that the torch song uses only verbs, the love song just adjectives.

The sense it leaves is that, in Sondheim’s mind at least, we humans like to think about and grade the quality of our love but that suffering is physical.

As researchers begin to delve into the evidence of Sondheim’s creative genius, other realizations and discoveries wait to be mined from the treasures of the Stephen Sondheim Collection. These anticipated discoveries will lead to new productions of Sondheim’s classic and lesser-known shows, inspire future generations of performers, teach Sondheim’s craft to aspiring songwriters and demonstrate how Sondheim’s songs are timeless.

Sondheim remains front and center in the American cultural consciousness, and it is fitting that his legacy finds a home at the nation’s library in time for America’s semiquincentennial.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!September 22, 2025

Nobody Would Edit Shakespeare, Right? Right?

This is a guest post by Patrick Hastings, a specialist in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

A contemporary production of one of William Shakespeare’s plays might cut lines for a snappier performance, and some directors will even eliminate characters or combine scenes for expediency. The plays might be set in Miami or Mantua, costumed in ’60s mod or medieval tunics. We are taught early on that we can cut and paste Shakespeare’s text, and we can put Richard III in a World War I uniform, but we do not change Shakespeare’s language. Prince Hamlet says, “How dost thou?” not “Wassup?”

But theater people were not always so precious about Shakespeare. The Rare Book and Special Collections Division holds no fewer than seven printings of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” that include an added deathbed conversation between Romeo and Juliet in the play’s final scene. The editorial introductions to these editions reveal changing attitudes toward the fixed nature of the text; they challenge our contemporary reverence for Shakespeare as an untouchable genius.

The first full edition of “Romeo and Juliet,” in 1599. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The first full edition of “Romeo and Juliet,” in 1599. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The first authorized, complete edition of “Romeo and Juliet” was published in 1599 and served as the source text for the 1623 First Folio of “Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies.”

By 1769, a new version of “Romeo and Juliet” — “as it is performed at the Theatre-Royal in Drury Lane” — had become popular. Published with alterations to the text made by an actor/director named David Garrick and first staged in 1748, this edition eliminates references to Rosaline (Romeo’s initial love interest), reduces the role of Mercutio and, most notably, adds a 67-line final conversation between Romeo and Juliet.

In Garrick’s version of Act 5, Scene 3, Juliet wakes up after Romeo takes the poison but before he dies. (“O true apothecary! Thy drugs are not so quick” in Garrick’s version.) The lovers share a melodramatic final conversation, and then Romeo dies in Juliet’s arms. Subsequent 1794, 1814, 1819 and 1874 editions of “Romeo and Juliet” adopt Garrick’s alterations to Shakespeare’s original text.

The stage actor David Garrick revised parts of “Romeo and Juliet” and his version gained popularity for decades. Artist: Benjamin Wilson, 1754. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The stage actor David Garrick revised parts of “Romeo and Juliet” and his version gained popularity for decades. Artist: Benjamin Wilson, 1754. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The prefatory notes to these editions provide context and justification for retaining Garrick’s changes. Some simply prefer Garrick’s version over Shakespeare’s. A few claim that Garrick’s alterations are more faithful to the original 16th-century sources that Shakespeare used for the story of “Romeo and Juliet,” including an Italian novel by Bandello.

After more than a century of preference for printing Garrick’s altered version of “Romeo and Juliet,” attitudes begin to shift back toward Shakespeare’s original text in the late 1800s. An 1882 edition reprises the figure of Rosaline, and Romeo dies immediately after taking the poison without the deathbed conversation added by Garrick.

Chasing these changes from edition to edition through time eventually leads us back to where we started; in 1886, a multivolume series of Shakespeare’s plays publishes a facsimile of the 1599 quarto edition of “Romeo and Juliet” along with a scholarly preface that demonstrates a concern for identifying the original text and introduces a practice for noting textual variants.

This focus on representing and honoring the true, authoritative text continues today, and we might be surprised to learn that readers haven’t always regarded a fixed version of Shakespeare’s plays with such “mannerly devotion.”

Rather, an altered version of the text was a “trespass sweetly urged” for over a century.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!September 18, 2025

Snakeskin Bookmarks (Yes, Really)

Linnea Vegh was working at a large, well-lit workspace in the Conservation Division on a recent day, considering an unusual problem in an 1869 Persian-Arabic dictionary published in India: snakeskin.

Staff in the African and Middle Eastern Division had found five pieces of snakeskin — thin, desiccated, brownish, each several inches long — among the 500 or so brown, brittle pages of “Muntakhab al-lughāt,” a lithograph produced in Lucknow, India, by the influential Nawal Kishore publishing house. It’s one of several hundred rare Persian-language lithographs that Vegh is preparing for scanning and digitization.

The repeated usage implies that, unlikely as it might seem, “they were probably used as a convenient bookmarker,” said Vegh, who, as one of the Library’s book conservation technicians, is familiar with finding weird things in old books. In this collection alone, she’s found “leaves, flowers, insects, spiders … breadcrumbs, tobacco and of course lots of handwritten notes.”

Welcome to the world of “inclusions,” an ecosystem known to archivists the world over in which they come across all sorts of things readers have purposefully or inadvertently left between a book’s pages. Time passes, the item is forgotten, the book goes to a library or museum and, decades or centuries later, an archivist turns the page to find a talisman.

Modern readers do this all the time, using something at hand for an impromptu bookmark — a letter, receipt, pencil, note, a $1 bill — and so did their long-ago peers. Sometimes people will press autumn leaves between pages for preservation. Other times, readers will tuck a love letter or special note into a book — perhaps at a meaningful spot in the narrative — for a private memory.

All of these may or may not be meaningful to researchers and scholars, prompting a professional quandary: What to do with this stuff?

Breadcrumbs, bugs and tobacco aside, technicians check with curators to see how they want items to be preserved and where. Pressed leaves, for example, are nice but they are acidic and damage the book over time, so they might be preserved separately.

This unsigned sketch was another unexpected find in the dictionary. African and Middle East Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

This unsigned sketch was another unexpected find in the dictionary. African and Middle East Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.And that, as it turns out, is the same strategy for snakeskin that is likely more than 150 years old, of uncertain provenance with an unknown meaning.

So Vegh began her work in one of the Library’s conservation labs, a windowless room in the basement of the Madison Building, across the street and miles removed from the glamour of the Jefferson Building’s Great Hall.

Vegh first mounted the snakeskins in a sink mat (a slender shadow box), covered it with mylar and placed it within a hinged cover. She then set this inside the preservation box of the book itself. This will allow the snakeskins to be digitized, kept with the book and seen by scholars without having to be handled.

This might seem overly cautious, but the Library measures time in centuries. Who can know what future technologies or insights may come? Who, in 1869, would have predicted DNA or hyperspectral imaging?

“We’re always talking about how you can’t really know what future scholars and researchers will want to see or know about these items in the future,” Vegh said. “So we really try to be conservative in terms of keeping everything together as much as possible.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 16, 2025

Dell Mapbacks: Bright and Cheesy

They just popped off the rack in the midcentury, those Dell mapbacks, the pulp series with dramatic, cheesy covers and bright maps on the back. Who could resist?

Guys, dames, gunshots, cops, killers, a little romance, a little naughtiness — they had it all, kid. “Curtains for the Copper.” “Hearses Don’t Hurry.” “Blood on the Black Market.” “Memo to a Firing Squad.” Big-shot writers like Agatha Christie, Dashiell Hammett, Erle Stanley Gardner. Top-shelf artists such as Ruth Belew, Robert Stanley and Gerald Gregg. That Dell logo, or colophon, an eyeball staring at you through a keyhole, a nice little voyeuristic touch.

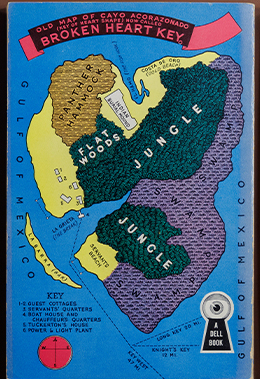

Flip the title over, and there was a color map of the house where this guy got dead, that island where things went south, these cutaway floor plans, those mean streets.

They were crazy popular, too, starting in 1943 and running for more than 600 titles for nearly a decade. Mostly mysteries, nearly all reprints of earlier hardcover titles, sure, but a few romances, Westerns, sci-fi and nonfiction narratives from World War II thrown in. Put them together and you have a slice of Americana at the middle of a difficult century, a country emerging as one of the world’s great powers but still uneasy with itself, letting off a little cultural steam.

The maps for “Midnight Sailing,” “The Iron Spiders” and “The Strawstack Murders.” Rare Book and Special Collections Divison. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The maps for “Midnight Sailing,” “The Iron Spiders” and “The Strawstack Murders.” Rare Book and Special Collections Divison. Photo: Shawn Miller. You can go down quite the rabbit hole with the Library’s collection of these in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, a near complete run of the series. It’s courtesy of Helen Meyer, the chair of Dell Publishing Company, who orchestrated their donation to the Library in 1976 as part of a larger collection of more than 6,000 titles. (They’re available in used bookstores and online, too, most just for a couple of bucks.)

The mapbacks in particular, and Dell paperbacks in general, were cheap, compact and made to take anywhere. (True confession: I have 1949’s “The Corpse Came Calling” by Brett Halliday on my desk, and it is perfect in every way.)

These books didn’t mess around, either. There was a plot summary right up front, along with thumbnail character descriptions and a list of clues before the story even started.

Let’s meet our femme fatale in “See You in the Morgue,” a 1946 tale by Lawrence G. Blochman, a popular and prolific mystery writer of the era: “JULIA FRYE, who normally had the face of a Madonna by a highly stylized modern painter, but when she looked at Pierre she was an untamed animal.” Next, we learn PIERRE LAURENT teaches French and bridge (as one does), and is “sleek and glib, with a tiny hair-line moustache, an intriguing foreignness, and a way with women.”

Throw in some clues listed on the following page (“A crumpled, bloodstained HANDKERCHIEF… Artificial animal EYES … Mysterious telephone MESSAGES”) and we’re off to some all-caps MAYHEM.

A closer look at the mapback for “The Iron Spiders” by Baynard H. Kendrick. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A closer look at the mapback for “The Iron Spiders” by Baynard H. Kendrick. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Pulps of the period have long been fondly regarded by collectors, and mapbacks have been catalogued in several books and online sites, including the extensive The Mapback Index. They weren’t meant to last but they have — and taken together, they’re a small window into another time, preserved at the Library, where they remain a delight.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 9, 2025

Justice Barrett Offers Insight Into Court’s Inner Workings

Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett took the stage early Saturday morning at the National Book Festival to talk about her new book, “Listening to the Law: Reflection on the Court and Constitution,” to a crowd that filled a ballroom.

She was the first justice to speak at the book festival since Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the justice she replaced on the nation’s top court.

Interviewed onstage by festival co-Chairman David M. Rubenstein, Barrett said she wrote the book so that Americans could see how the court works and to “feel pride” as the nation approached its 250th birthday.

“The drafting of the Constitution has been called the ‘Miracle at Philadelphia,’” she said, referring to the city in which the document was debated and signed in 1787. “And I think it really was a miracle … it has lasted because each generation has taken it and made it its own.”

Barrett, 53, was a Notre Dame law professor and serving on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Indiana when she was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Trump in 2020, just weeks before the presidential election. (She had been a finalist in 2018, after the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy.)

Trump, when introducing her as his nominee, described her as “one of our nation’s most brilliant and gifted legal minds.”

Born in New Orleans, she was the oldest of seven children and now has seven children with her husband, Jesse Barrett. She obtained her law degree at Notre Dame (meeting her husband in the process) and, she told the crowd, the family was happy there before her nomination.

“My husband and I have plots at Notre Dame in the cemetery there,” she said, “so I really thought that’s where we were going to stay.”

Her conversation Saturday morning touched on how she comes to her decisions, indicating it’s not a cut and dried process.

“I try to keep an open mind,” she said. “One thing I try to communicate in this book is that every step of the decision-making process is really important and it matters. So, I go into (judicial) conference knowing what I think, but I do listen to my colleagues, and I will adjust what I think about how we should approach the opinion based on what my colleagues say.”

Justice Barrett also provided the audience with details about the daily business of the court.

The justices do not discuss cases before oral arguments; sometimes the oral arguments are so good they can cause her to change her mind about at least part of her opinion; one of her four clerks writes the first draft of her opinions, then she rewrites and edits as needed; when her opinion is circulated among justices, sometimes a fellow justice will ask for a small change before signing on; and, finally, the most recent justice has to oversee the court’s cafeteria and open the door when someone knocks during their discussions.

Another book while she’s on the bench isn’t in the offing, she said, calling the publication a “one and done.” She had to find time over the past several summers to write while the court was in recess, she said, and free time is at a premium.

“It was an arduous process writing the book, to be honest,” she said with a smile, drawing a laugh from the crowd. “I’m not sure I would repeat it just because it did take so long. I have seven children and another job.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 8, 2025

The Library’s 2025 Literacy Award Winners

This is a guest post by Judith Lee, the Literary Awards program manager.

In 1973, volunteers set up a modest literacy program in New York City, working to help parents and their children gain reading skills to improve their lives in a foundational way. Over the decades, Literacy Partners grew into a nonprofit with more than 30 full-time staffers in eight states and Puerto Rico.

Today, 52 years later, the program’s two-generation approach won the Library of Congress’ top honor in the 2025 Literacy Awards, the $150,000 David M. Rubenstein Prize, bringing the organization resources and national acclaim.

Acting Librarian of Congress Robert Newlen made the announcement today — World Literacy Day — awarding the annual program’s four top prize winners and 20 honorees. The groups were awarded a total of $525,000, all going to literacy-building nonprofits working around the world, and all funded by philanthropic donations.

“The 2025 winners and honorees have demonstrated a commitment not only to individuals but also the communities in which they live,” Newlen said.

For agencies that often work in low-income and difficult circumstances, the awards and recognition hit home.

“We are deeply honored to have our work recognized by the Library of Congress,” said Kristine Cooper, Literacy Partner’s chief external affairs officer. “This recognition affirms not only the strength of our mission, but also the lasting impact literacy has on generations to come.”

In Memphis, Tennessee, Literacy Mid-South received the $100,000 Kislak Family Foundation prize for its outsized impact on literacy development relative to its small size.

The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Prime Time Reading Program received the $50,000 American Prize for their outstanding work. Photo courtesy of Prime Time.

The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Prime Time Reading Program received the $50,000 American Prize for their outstanding work. Photo courtesy of Prime Time.In New Orleans, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Prime Time Reading Program received the $50,000 American Prize for equipping families with the tools and habits to make reading a shared and enriching part of daily life.

Finally, Building Tomorrow, a former Literacy Award Successful Practices Honoree, received the $50,000 International Prize for teaching literacy and increasing access to education in Uganda. The program has been such a success that it recently expanded into Rwanda.

“Building Tomorrow was a proud Successful Practices Honoree in 2023, and receiving this even greater recognition in 2025 is a humbling validation of the momentum building around community-powered education,” said George Srour, Building Tomorrow’s co-founder.

The Library’s Literacy Awards, established in 2013 with Rubenstein’s support (and bolstered by the Kislak Family Foundation in 2023) has awarded 247 prizes, totaling more than $4.3 million. More than 200 organizations from 42 countries have been recognized for their work.

Nonprofit organizations, schools, libraries and literacy initiatives from across the country and around the world apply for the awards every January. The 15-member Literacy Awards Advisory Board then reviews the applications before the Librarian of Congress makes the final decisions.

This year’s other international honorees were in Kenya, Scotland, Nigeria and South Africa. There were 15 other U.S. honorees, ranging from locally focused efforts to nationwide campaigns.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers