Library of Congress's Blog

January 22, 2026

Forging Bonds: The Veterans History Project Turns 25

—This is a guest post by Travis Bickford, the head of the Program Coordination and Communications Section of the Veterans History Project. It also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Preserving the personal narratives of our nation’s veterans has the power to connect and reunite people. These stories link generations, bridge cultural and geographic divides and build lasting bonds between families, friends and even strangers.

The Veterans History Project at the Library was born out of a family moment. Former congressman Ron Kind attended a backyard gathering and listened as his uncle and father swapped war stories. He realized the value of those kinds of stories and the importance of preserving them. Soon after, he brought the idea to Congress.

Since its founding by Congress in 2000, VHP has blossomed into an archive of stories from over 121,000 U.S. military veterans. Those stories are used in all kinds of ways — perhaps by Ken Burns for a documentary film, by Liza Mundy for a bestselling book, by a family member who just wants to hear a loved one’s voice again or by your neighbors, simply because they’re interested in World War II history.

VHP unites and even reunites people — witness the story of the Pacific war POW diaries from the Robert Augur and George Pearcy collections.

Pearcy and Augur were captured by the Japanese in the spring of 1942 in the Philippines following the Battle of Corregidor. According to Pearcy’s diaries and records, they were incarcerated together at Cabanatuan Prison Camp, just north of Manila. Veterans often speak of the intense relationships they develop with fellow soldiers while deployed. Augur and Pearcy were no exception and became fast friends.

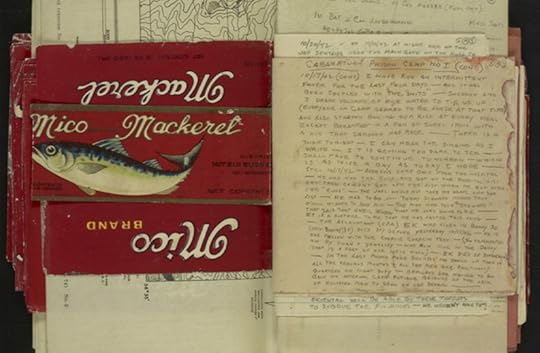

The scarcity of paper in remote places in the Philippine islands made diaries like these rare. Augur journaled in a small Japanese notebook. Pearcy documented his experiences on whatever he could find: old maps, hospital forms, the back of labels peeled from tins of mackerel. He wrote about his memories of Bataan, illnesses he’d suffered, things he wanted to do when he got back home, life at Cabanatuan — the beatings of prisoners, the decapitation of a guard, attempted escapes.

George Pearcy used this label from a can of mackerel for his diary. Veterans History Project. Photo: Shawn Miller.

George Pearcy used this label from a can of mackerel for his diary. Veterans History Project. Photo: Shawn Miller.After over two years at Cabanatuan, Pearcy was selected to board a prison ship headed to a labor camp in Japan in the fall of 1944. Augur, whose leg had been amputated because of injuries suffered in battle, stayed behind. Just before shipping out, Pearcy gave his diary and letters to Augur and asked him to send them to Pearcy’s family in case he didn’t make it home.

Sure enough, Pearcy’s ship was torpedoed by a U.S. submarine, and he perished. Augur was released in 1945, after the war, and sent his friend’s documents to Pearcy’s parents.

Seventy years later, Pearcy’s family donated the diary and letters to VHP. And after reading a blog post written by a VHP staff member about the Pearcy diary, Augur’s family contacted the Library and donated his diary, too — reuniting the two friends in the VHP archives.

Last year, those diaries were displayed side by side in a new Library exhibition, “Collecting Memories: Treasures from the Library of Congress.” When the exhibit opened, VHP invited the Pearcy and Augur families to attend, bringing them together for the first time. They shared a private lunch at VHP’s info center in the Jefferson Building. Many tears were shed — happy tears.

Pearcy’s family donated photos and diaries to the VHP. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Pearcy’s family donated photos and diaries to the VHP. Photo: Shawn Miller.In the summer of 2024, VHP hosted the family of a Korean War veteran, 1st Sgt. Richard Owens, at a ceremony marking the donation of the late patriarch’s collection. The event resembled a mini reunion, bringing together almost 20 family members spanning three generations and multiple states to honor his legacy as a Marine, father, grandfather, uncle and brother.

Owens served in the Marines for 20 years — including as an infantry machine gunner in the Korean War — and continued on active duty and in the Marine Corps Reserves until 1990.

Documenting veterans history helps create new relationships, too.

Author Liza Mundy and science educator Bill Nye met after Mundy referenced Nye’s mother in her 2017 bestseller, “Code Girls: The Untold Story of the Women Code Breakers of World War II.”

Over 10,000 women with skills in mathematics and languages were recruited as cryptographers (codemakers) and cryptanalysts (codebreakers) and tasked with breaking German and Japanese codes.

These women were sworn to secrecy, so decades passed without anyone knowing how vital their role was in helping the Allies end the war — a demonstration of the importance of preserving and making accessible as much of their history as possible.

A former “Code Girl” attends a 2019 Library event that celebrated their work. Veterans History Project. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A former “Code Girl” attends a 2019 Library event that celebrated their work. Veterans History Project. Photo: Shawn Miller.Mundy had used VHP and other Library collections extensively while researching her book. Nye, whose mother was a Code Girl, saw his mother mentioned in the book and in 2017 emailed Mundy about it. Two years later, VHP hosted a reunion for Code Girls, featuring both Mundy and Nye as guest speakers. There, Nye donated materials from his mother’s World War II service, allowing her story to live on.

And for Mundy and Nye, the Code Girls story had an especially happy ending: They got married in 2022.

John Stavast’s military career began in World War II as an Army infantryman and ended with his retirement in 1980. In 1949, after a three-year break from serving, he moved to the Air Force to become a pilot.

In 1967, Stavast, flying his 91st combat mission, was shot down in North Vietnam and incarcerated for more than five years at the infamous Hanoi Hilton. While imprisoned, Stavast kept a roster, handwritten on camp toilet paper, of every pilot who was captured and imprisoned with him — including future Sen. John McCain. That roster currently is held in the VHP archives, along with seven unique collections from pilots who also appear on Stavast’s list.

John Stavast (right, with cap) smiling at a welcome home event in his honor in Claremont, California, in 1973. Photo: Unknown. Veterans History Project.

John Stavast (right, with cap) smiling at a welcome home event in his honor in Claremont, California, in 1973. Photo: Unknown. Veterans History Project.After he was released, doctors confirmed that Stavast had suffered broken bones in his back, arms and legs, a skull fracture and a fractured jaw — just some of what he endured while imprisoned for over half a decade. And that’s only his story. It’s likely some POWs on that roster forged a familial bond with each other, which makes capturing their stories and reuniting them at VHP all the more necessary.

The personal narratives housed within VHP’s archive help reunite and connect people, by keeping veterans’ legacies and memories alive. Doing so often helps keep a family’s legacy or a military unit’s history alive, too.They create an avenue to hear a lost loved one’s voice again, to read an old letter again or to see a face again in a video or photo.The Veterans History Project is more than just practical. It connects people across past, present and future generations on a personal level.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 14, 2026

About Mom’s Chocolate Chip Cookie Recipe…

Once upon a time many years ago, I called long distance to ask my mother, who still lived in our little farmhouse in the Mississippi countryside, if she might tell me the recipe for her magical chocolate chip cookies.

I had long since moved away from my rural childhood home, all the way to a Big City in the North. Cooking a few things from the old country had proven to be a way to keep in touch with my Southern roots, and an earlier trip back home to my grandmother’s house had been a delightful time in learning to make her fried apple pies. There was no recipe and no plan; she’d been making them from scratch all her life and thought it both sad and hilarious that I was writing it down.

No doubt my mom’s cookies had the same sort of provenance. Her kitchen had all sorts of banged-up hand mixers and warped rollers and culinary doodads that that had been handed down over the eons.

Mom — her name was Betty — was a bit flustered when she answered my call, but she didn’t need to look this up.

“I make them just like my mother made them,” she said.

Great, I said, pen and paper at the ready. This was really going to be special. How I would charm dinner guests with these Tucker family originals!

The rest of the conversation went something like this:

Mom: “So you’ve got a cookie sheet and everything like that?”

Me: “Yes, ma’am.”

Mom: “Okay, so the first thing, you’ll want to go to the store and get you a bag of Nestle Toll House chocolate chips.”

Me: (scribbling) “Got it!”

Mom: “And the recipe is right there on the back.”

Me:

Mom: “Hello?”

Me: “I —”

Mom: “That’s just how Mamaw made them. And they’re so good!”

I was crushed. The cookies I cherished, the wonders from Mamaw’s old Southern kitchen, were … a corporate promo? Was nothing sacred?

This, it turns out, was a generation-wide realization – the same scenario was a later a popular skit on a “Friends” episode (“nesssuhlll tollHAUSseee”) – a clip of which now has millions of views on social media platforms.

So of course I read every word of my Library colleague JJ Harbster’s wonderful piece over the Christmas holidays about how the Nestle’s “corporate” recipe was actually the homemade concoction of Ruth Graves Wakefield, who, no kidding, invented the chocolate chip cookie in the late 1930s.

The Toll House Inn

, where Ruth Wakefield sold the first chocolate chip cookies. Pictured here in 1984, it later burned down. Photo: John Margolies. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Toll House Inn

, where Ruth Wakefield sold the first chocolate chip cookies. Pictured here in 1984, it later burned down. Photo: John Margolies. Prints and Photographs Division.She and her husband ran the popular Toll House Inn in Whitman, Massachusetts, a small town south of Boston. Wakefield was experimenting with cookie recipes when she decided to chop up a Nestle semisweet chocolate bar and drop the chunks into the batter. The chunks didn’t spread out during baking, and thus the chocolate “chip.”

She called them the “Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookie” (she baked them to a crispy finish) and they were an instant hit, spreading nationwide via her 1938 cookbook, “Toll House Tried and True Recipes,” mass-market radio shows and newspaper articles. It was so popular that a year later, Nestle asked if they could feature her recipe on the back of their chocolate bars. They even altered the product to come in morsel-sized bits, expressly for cookie use.

And no doubt that’s how my grandmother, aka Mamaw, would have come across a bar or a bag of Nestle’s chocolate in a tiny grocery store in Clarksdale, Mississippi, sometime in the late 1930s. She would have looked on the back of the package and thought, “I’ll try that.” My mother would have been 7 or 8.

Wakefield’s recipe became so popular so quickly — particularly with an effective Nestle ad campaign to send the cookies to soldiers serving overseas in World War II — that the postwar generation grew up with the same cookie, from Massachusetts to Mississippi and beyond. They really were homemade, really did seem to be your mom’s own creation and really were dusted with a dash of childhood magic.

And besides, those cookies really were good.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 12, 2026

From “Happy Days” to “The Love Boat,” Charles Fox’s Themes Were Always Exciting and New

This article also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

For millions of Americans in the 1970s and ’80s, Charles Fox was the sound of weeknight entertainment.

You came home from work, gathered with the family in the living room after dinner, sprawled on a beanbag chair, turned on the TV and out came a song composed by Charles Fox.

“Love, exciting and new. Come aboard, we’re expecting you.”

“Schlemiel! Schlimazel! Hasenpfeffer Incorporated! We’re gonna do it!”

“Sunday, Monday, happy days.”

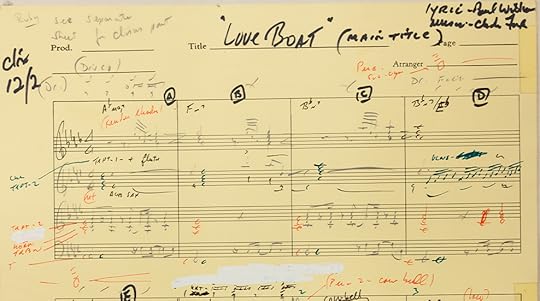

“The Love Boat” working sheet music. Music Division.

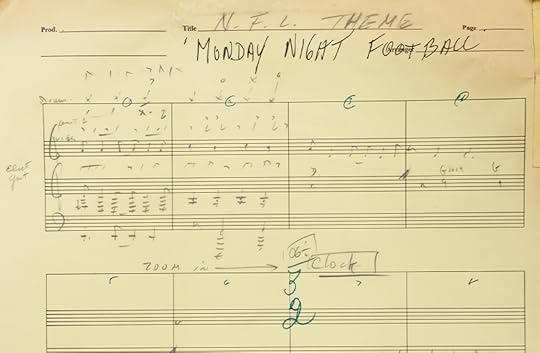

“The Love Boat” working sheet music. Music Division.Fox composed the theme songs for some of the era’s biggest and most fondly remembered TV shows: “The Love Boat,” “Happy Days,” “Laverne and Shirley,” “Wonder Woman,” “The Paper Chase.” He wrote the original theme for “Monday Night Football.” With his score for “Wide World of Sports,” he made a catchphrase of “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.”

In the days before streaming or widespread cable, television was a communal experience, with an audience not yet fragmented by endless channels and choices. Much of the nation watched the same shows and heard the same theme songs, embedding them in the popular consciousness: “300,000,000 people hear his music weekly,” the headline of a trade journal cover story on Fox noted in 1979.

Fox had an incredibly varied career. He wrote the themes for popular game shows such as “Match Game,” “What’s My Line?” and “To Tell the Truth.” He composed ballets and scores for musical theater. He arranged for Latin jazz legend Tito Puente and for “The Tonight Show” band. He scored over 100 films: the Oscar-nominated drama “Goodbye Columbus,” the kitschy sci-fi “Barbarella,” the dramedy “9 to 5.” He earned Oscar nominations for his songs from the films “Foul Play” and “The Other Side of the Mountain.”

An early draft of Charles Fox’s theme for the first broadcasts of “Monday Night Football.” Music Division.

An early draft of Charles Fox’s theme for the first broadcasts of “Monday Night Football.” Music Division.And he wrote popular hits that still resonate today — especially the classic “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” a No. 1 hit for both Roberta Flack in 1973 and, in 1996, the Fugees.

Fox didn’t work alone. He composed the music, a partner wrote the lyrics. Most often, that was Norman Gimbel, who made a name for himself in the 1960s by writing the English lyrics for Brazilian bossa nova classics like “The Girl from Ipanema.” Together, Fox and Gimbel created a soundtrack for the ’70s: among others, “Happy Days,” “Laverne and Shirley,” “Wonder Woman,” “Killing Me Softly” and “I Got a Name,” a top 10 hit for an up and- coming singer-songwriter named Jim Croce.

Fox donated a trove of his papers to the Library’s Music Division, mostly consisting of works for television. The papers reveal Fox’s way of working. Elements change from draft to draft; “realizing defeat” stands in for “agony of defeat” in an early “Wide World of Sports” score. A timing sheet shows the precision required for scoring a film or TV show, denoting how the music syncs to the video second by second — the famous “cut to skier falling — agony of defeat” comes precisely 13.5 seconds into the theme.

In his 2010 memoir, “Killing Me Softly: My Life in Music,” Fox wrote that he aimed to compose music so attractive that people would hear the theme, leave the refrigerator and happily turn back to their TV sets.

“The theme,” he wrote, “should feel like a good friend, an old friend who comes back each week to entertain you.”

And were we not entertained?

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 8, 2026

A Globe That’s Out of This World

—This is a guest post by Julie Stoner, a reference librarian in the Geography and Map Division. It also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

For millennia, people have attempted to capture the wonder of the heavens, to make the movements of the stars and planetary objects comprehensible to ordinary minds. One method was the armillary sphere — a model of the heavens featuring a central globe within a framework of rings representing celestial bodies.

The Geography and Map Division’s oldest globe, and one of its rarest, is an armillary sphere created by Caspar Vopel in 1543.

The German mathematician and geographer operated a prominent workshop that produced celestial and terrestrial globes, armillary spheres, sundials, quadrants and astrolabes. Nine of his globes are known to exist today, including the exquisite example held by the Library.

The Library’s armillary sphere consists of a terrestrial globe only 3 inches in diameter, bearing a hand-drawn map with names of regions written in red and the location of important cities marked with red dots. Geographers of the era weren’t certain whether the Americas and Asia were the same continent or separate landmasses; Vopell drew his globe showing the two landmasses connected.

The globe is contained within 11 interlocking armillary rings that illustrate the rotation of the sun, moon and stars in the Ptolemaic tradition, with the Earth at the center of the universe. The rings include the equator, the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, the equinoxes, the polar circles and the ecliptic circle of the sun. Some of the rings move and could be used to demonstrate the movement of the stars during different seasons.

Ironically, this globe was produced the same year Nicolaus Copernicus published his heliocentric model of the universe, which mathematically proved that the Earth revolves around the sun, revolutionizing the way humans saw their place in the universe.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 29, 2025

Ancient History Unfolded

—This is a guest post by Gwenanne Edwards, a conservator in the Conservation Division. It will appear in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The majority of Library’s physical collections are, as you might think, on paper. But before paper was invented in China and introduced globally, papyrus dominated as the writing surface of the Mediterranean world. Made from a freshwater sedge found in the Egyptian Nile valley, papyrus was used as a writing surface as early as 3000 B.C. The earliest text on papyrus at the Library is from around 2000 B.C., held in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

A recent Library workshop focused on the conservation treatment of papyrus texts from the African and Middle Eastern Division.

These texts, which come from Egypt and date from the 7th to 11th centuries A.D., are written primarily in Arabic with a few in Greek and Coptic. They were recovered from a midden (a refuse heap) in Fustat, an area now part of Cairo.

The texts are administrative, documenting practical or legal accounts — decrees, contracts and other records. Because of their condition prior to conservation, the contents of most of the papyri have not yet been fully studied. Before conservation, many of the Fustat papyri were fragmentary, covered in dirt and debris and crumpled and folded with fibers askew, obscuring the text.

Conservators cleaned and stabilized the papyri by unfolding and aligning fibers and fragments and reattaching delaminating fibers and loose or detached fragments. Papyrus becomes extremely fragile and brittle over time, so conservators introduced humidity to make the papyri more flexible, allowing fibers to be unfolded and aligned safely.

Many of the Egyptian papyri treated by conservators were crumpled fragments, covered in dirt and debris. Shawn Miller.

Many of the Egyptian papyri treated by conservators were crumpled fragments, covered in dirt and debris. Shawn Miller.After conservation, the papyri will be digitized so that they can be studied by researchers.

Conservation of the Fustat papyri is meticulous work, with immense rewards. By removing debris and opening creases and folds, conservators reveal previously obscured text. Fragmentary as they are, these texts give us glimpses into social, economic and political history, adding to our knowledge and understanding of late antiquity and the post-ancient world.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 19, 2025

Remember Pierre Chambrun? He Has Your Reservation at the Beaumont Hotel. (Just Watch Out for the Other Guests.)

—This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, a writer-editor in the Publishing Office. It will also appear in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

A poisoned opera prompter. A conjure-man bludgeoned with a bone. A hat-pin used as a murder weapon. A cat burglar jumping across the roof of a chateau. A police chief draining a lake to look for a missing girl.

These characters and hundreds more can be found in the Library of Congress Crime Classics series. Launched in April 2020, the critically acclaimed series features some of the finest American crime writing from the 1860s to the 1960s. Drawn from the Library’s collections, each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author bio, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger.

This past summer, the Library published the 20th title in the series “Uncle Abner”; the most recent one, “The Cannibal Who Overate,” hit shelves Dec. 9.

“Cannibal,” first published in 1962 by Hugh Pentecost (the pen name of the wildly prolific Judson Philips), marks the debut of Pierre Chambrun, hotel manager and amateur sleuth extraordinaire. He’ll go to any lengths necessary to protect the reputation of his beloved Beaumont Hotel, New York City’s finest. In this, his first adventure, his wealthiest and most obnoxious guest, Aubrey Moon, is so loathed that a club has formed to kill him before his over-the-top birthday party at the Beaumont, which means Chambrun has work to do.

Chambrun and his fictional hotel were a hit, continuing for more than 20 books over the next 26 years.

Many of the Crime Classics books in the series, such as this one, also focus on New York City. But mysteries also abound in a Massachusetts women’s college; the backwoods of West Virginia; a small town in Ohio; Los Angeles and Boston; the Mexican desert; the gorgeous French Riviera; the fog-filled streets of Victorian London; and even the Metropolitan Opera’s backstage.

Historic firsts are presented: the first full-length American detective novel (“The Dead Letter,” from 1866); the first female sleuth to appear in a crime novel series (Amelia Butterworth in “That Affair Next Door,” from 1897); the first novel to feature a Black detective and all Black characters (“The Conjure-Man Dies,” from 1933); and the first police procedural (“V as in Victim,” from 1945).

Whether you enjoy witty short stories, longer complex novels, detectives who use scientific instruments or sleuths who crack cases using their fists, there’s something for all mystery lovers in the series — and all of them are avaiable in the Library of Congress Store and from booksellers worldwide.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 18, 2025

Hallelujah for Handel’s “Messiah”

The Christmas season is filled with cherished traditions, and one of them is George Frideric Handel.

Few works in Western classical music achieved the enduring popularity of Handel’s 18th-century oratorio “Messiah” — the thrilling power of its “Hallelujah” chorus has given audiences goosebumps for 283 years and counting.

And unlike many works or composers, “Messiah” never went out of fashion, never needed to be “rediscovered.”

Handel’s masterwork, which chronicles the prophecy, birth, crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, originally was most associated with Easter. Over time, especially in the U.S., it became a Christmas tradition, performed in big city concert halls, college auditoriums and small-town churches just down the road. The “Messiah” singalong is a ’tis-the-season programming staple for major performing arts centers and community chorales alike.

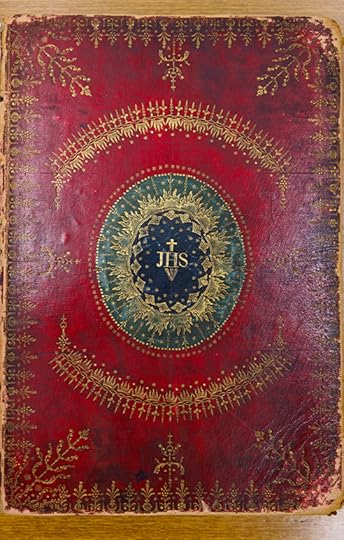

The red leather cover of an early edition of Handel’s “Messiah.” Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.

The red leather cover of an early edition of Handel’s “Messiah.” Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.The Music Division collections hold testaments to that tradition’s roots: a variety of 18th-century printings of selections from the work as well as complete scores.

Handel debuted “Messiah” in Dublin in April 1742. The first complete score, however, wasn’t published until 25 years later — eight years after Handel’s death. The Music Division’s earliest complete orchestral score is bound in sumptuous red leather, brilliantly gilded. The letters “IHS” — a Christogram for the Latin Iesus Hominum Salvator, or Jesus, Savior of Mankind — lie within a circle of angels and stars.

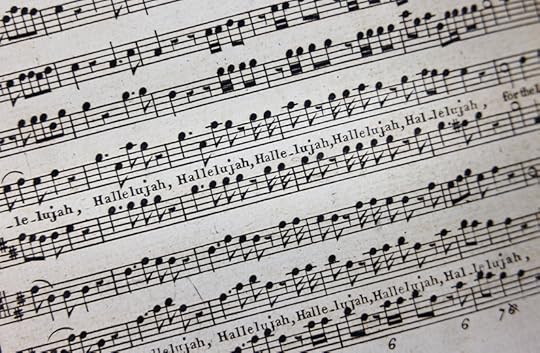

A close-up of the famous “Hallelujah” chorus. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.

A close-up of the famous “Hallelujah” chorus. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.The frontispiece presents an elaborate portrait of the regally dressed composer, followed two pages later by a list of subscribers who would be buying this, his latest work — starting with King George III and Queen Charlotte and the Dukes of York, Gloucester and Cumberland. Also on the list: Charles Jennens, the wealthy arts patron who compiled the “Messiah” libretto (he got three copies).

Inside, from the first words of “Comfort Ye” to the final “Amen,” Handel delivers high drama, memorable arias and stirring choruses that peak over and over again and bring back audiences again and again — as they have now for nearly three centuries.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 12, 2025

Louder than Words: The Lives of Johnathan Larson and Leonard Bernstein

— This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a public affairs specialist in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In a page among the Library’s Jonathan Larson Papers, the visionary composer and playwright mused: “… if I want to try to cultivate a new audience for musicals I must write shows with a score that MTV ears will accept.”

Larson’s collection is not the largest in the Library’s Music Division, but among the roughly 15,000 items included within it are scripts, personal writings, programs, correspondence, recordings, lyric sheets and even floppy disks that provide an intimate look into the mind of a generational artist.

Larson, who also was a lyricist and performer, once wrote that “creating rock operas” was his “true calling.” Although he died tragically young in 1996, the contemporary themes and style of his works — modern, introspective, political — have continued to inspire creators and audiences alike.His most well-known musical, the Tony Award- and Pulitzer Prize-winning “Rent,” has been staged around the world and was adapted into a 2005 film featuring many of the original Broadway cast. But it is an earlier project — Larson’s semiautobiographical musical “tick, tick … Boom!” — that influenced the 2021 Lin-Manuel Miranda film of the same name.

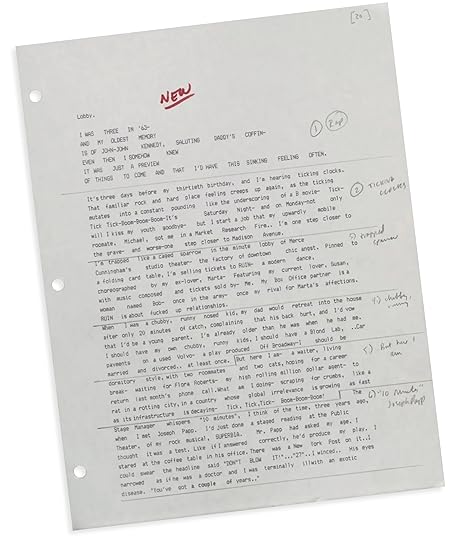

As his collection demonstrates, Larson’s “tick, tick … Boom!” was constantly evolving. His papers feature numerous iterations and evolutions of the musical’s script, which began as a one-man rock monologue called “30/90.” Promotional materials show that Larson later staged the show under the title “Boho Days” before settling on its final name.

A script draft of “Boho Days,” which was later renamed “tick, tick… BOOM!” Music Division. Used by permission of the Jonathan Larson estate. Music Division.

A script draft of “Boho Days,” which was later renamed “tick, tick… BOOM!” Music Division. Used by permission of the Jonathan Larson estate. Music Division.Miranda, who earned international acclaim for his groundbreaking musical “Hamilton,” played Larson in a 2014 revival of “tick, tick … Boom!” His movie fleshes out Larson’s story with insights from his papers and adds songs from the collection that did not appear in the composer’s original versions of the show.

Miranda was joined by scriptwriter Steven Levenson and theater historian Jennifer Ashley Tepper in a 2017 visit to the Library as part of the research for the film.

Tepper’s experience with the Larson Papers is extensive. As the creator of “The Jonathan Larson Project,” which completed its off-Broadway run earlier this year, Tepper began her research with the collection nearly a decade ago. In days spent poring through his written materials and listening to hours of recordings of Larson performing his own songs, Tepper discovered notes, reflections and ideas that revealed the depth of the artist’s passion and vision.

Tepper called her experience with the Larson collection “the adventure of a theatre historian’s wildest dreams.”

“The Jonathan Larson Project” originally began as a concert of Larson’s music in 2018, transforming over the years into a full-scale stage musical. It features around 20 lesser-known Larson songs, including music never before performed as part of a show, songs cut from “tick, tick…Boom!” and “Rent” and songs from unproduced shows, like Larson’s musical adaptation of “1984” and an original sci-fi musical called “Superbia.”

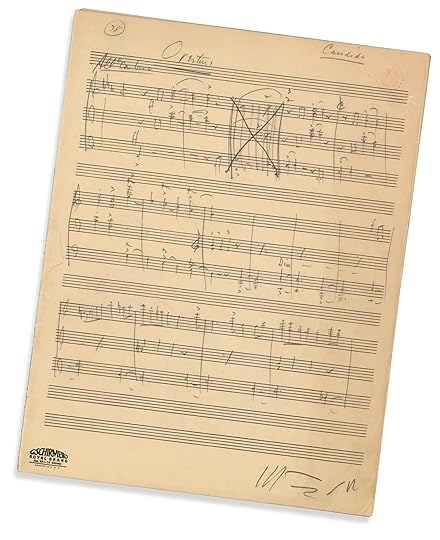

The expansive papers and manuscripts of another legendary Broadway figure, the renowned Leonard Bernstein, also were recently the subject of study for two films about the conductor-composer. Bernstein’s Broadway bona fides include “On the Town,” “Candide,” the short-lived “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” and the inimitable “West Side Story,” which itself received a modern film adaptation in 2021.

His more than 400,000-item Library collection includes materials not just from his professional life, but personal letters, recordings, scrapbooks, photographs and physical objects.

Leonard Bernstein’s license plate. Music Division.Bernstein is best recognized for his musical contributions, but his lifelong commitment to civil rights and work as a humanitarian were a major focus of Douglas Tirola’s 2021 documentary “Bernstein’s Wall.” The film weaves audio and images of the artist’s activism around societal issues — concerns about McCarthyism, civil rights and the war in Vietnam — with footage highlighting his personal life and musical genius.

Leonard Bernstein’s license plate. Music Division.Bernstein is best recognized for his musical contributions, but his lifelong commitment to civil rights and work as a humanitarian were a major focus of Douglas Tirola’s 2021 documentary “Bernstein’s Wall.” The film weaves audio and images of the artist’s activism around societal issues — concerns about McCarthyism, civil rights and the war in Vietnam — with footage highlighting his personal life and musical genius.Library staff helped the documentary team find and select images from the collection, including photos from Bernstein’s childhood and wedding — some of which appear in the finished film. Even more detail on this topic can be found in the Library’s collection, which holds materials documenting the many engagements and fundraising efforts Bernstein and his wife, Felicia Montealegre Bernstein, undertook for a range of causes.

The 2023 biographical drama “Maestro” from Bradley Cooper also drew many insights from the Library’s Bernstein Collection. The film’s team examined photos of Bernstein’s suits, a ring, his glasses and even re-created the musician’s “MAESTRO1” license plate for the movie. The Library has shared more about the “Maestro” team’s research process online and in the March/April 2024 issue of this magazine.

In cases like these, a line from the eighth Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam rings especially true: “A book used is fulfilling a higher purpose than a book which is merely preserved.” It remains a powerful mission to share the Library’s unparalleled collections so their stories can be interpreted through new voices and told to new generations (even if they don’t watch MTV anymore).

A music manuscript for “Candide” — part of the Bernstein papers at the LIbrary. Music Division.

Subscribe

to the blog— it’s free

A music manuscript for “Candide” — part of the Bernstein papers at the LIbrary. Music Division.

Subscribe

to the blog— it’s free

December 4, 2025

“A Marvel of Ingenuity” — The Library’s Main Reading Room

—This is a guest post by Jane A. Hudiburg, an analyst in the Congressional Research Service. It also appears in the September/October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In 1888, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the sixth Librarian of Congress, detailed his vision for the public reading room in the new Congressional Library — now known as the Thomas Jefferson Building. The space should follow the example set by the British Museum Library and be “circular or octagonal in form, so that all parts of it may be commanded” from the center.

To realize this panopticon concept, Spofford provided specifications for a “massive circular desk” that would give librarians and the Main Reading Room superintendent a view of every researcher, the card catalog and each alcove representing a major realm of knowledge.

Meanwhile, from the eye of the room’s domed ceiling, the figures in the aptly named painting “Human Understanding” could monitor the books springing forth from conveyor systems that connected the control room under the central desk to the stacks, the Capitol and eventually the John Adams Building and beyond. In her memoir “Thirty Years in Washington” (1901), Mary Cunningham Logan, the widow of Sen. John A. Logan, called the entire process — identifying, requesting and delivering books — a “marvel of ingenuity.”

The Library’s Main Reading Room as seen from high above. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Library’s Main Reading Room as seen from high above. Photo: Shawn Miller.Since that observation, the ingenious process has changed. The computer catalog replaced the card catalog; Electronic Book Paging phased out the call slips sent by pneumatic tubes; the book carrier pulled by continuously moving chains ceased operation, as did its replacement — a specialized elevator that lifted books from the control room into the reading room.

The tunnel to the Capitol, which once allowed the quick transport of materials to members of Congress, closed prior to the construction of the Capitol Visitor Center. And, the Library began providing content online, allowing researchers all over the world to access its digitized collections. Still, the mahogany central desk remains a powerful symbol — a direct connection between knowledge and its seekers and the never-ending quest to deepen and expand all human understanding.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 1, 2025

Literary Maps: Real Maps for Imaginary Places

The novelist started with a map.

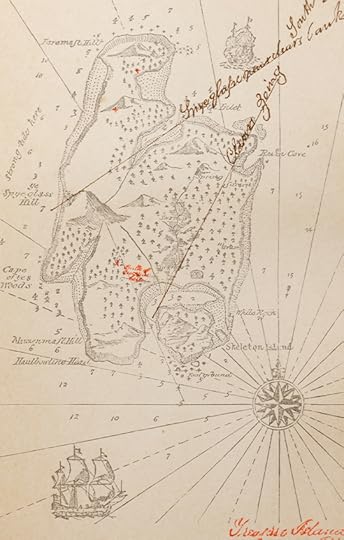

His name was Robert Louis Stevenson, it was 1881 and he was playing a game with his stepson when he sketched out an idea.

“I made the map of an island; it was elaborately and (I thought) beautifully colored; the shape of it took my fancy beyond expression; it contained harbors that pleased me like sonnets; and, with the unconsciousness of the predestined, I ticketed my performance ‘Treasure Island,’ ” he wrote years later. “… The next thing I knew, I had some papers before me and was writing out a list of chapters.”

The center section of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” map, with landmarks named and outlined. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The center section of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” map, with landmarks named and outlined. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.“Treasure Island,” the adventurous story of a boy, gnarly pirates and a treasure map, would become one of the most influential novels of the era. Stevenson’s sketch has become one of the most famous literary maps in world literature.

The Library preserves a first edition of Stevenson’s classic, along with dozens of other famous examples that have created a unique subset of the literary imagination over the centuries. There are so many that in 1999 the Library published “Language of the Land: The Library of Congress Book of Literary Maps” as a companion volume to the exhibition “Language of the Land: Journeys into Literary America.” Both drew on some of the 230 literary maps held in the Geography and Map Division.

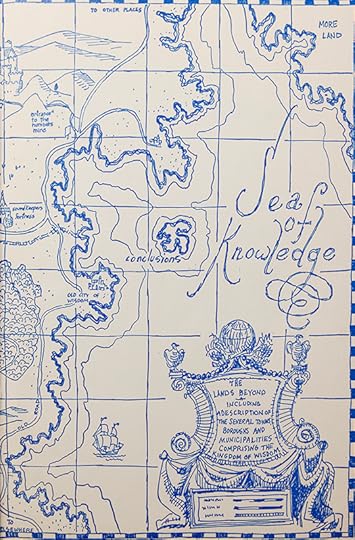

After all, what would “The Lord of the Rings” be without its map of Middle-earth? If 18th-century readers of “Gulliver’s Travels” didn’t have a map to go along with Jonathan Swift’s satirical prose, how would they know where the fictional island of Lilliput — with its diminutive citizens — could be found? What sense could kids have made of “The Phantom Tollbooth” without legendary artist Jules Feiffer’s map of The Lands Beyond?

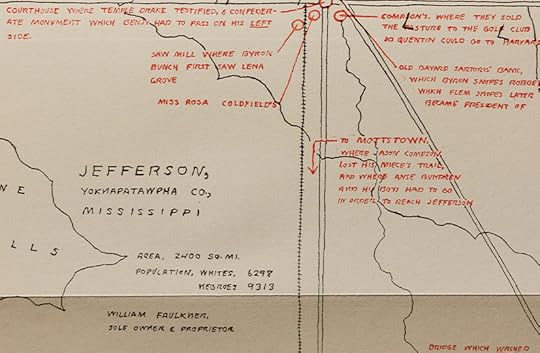

Here on a table in the soft light of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division is a first edition of William Faulkner’s “Absalom, Absalom!” with a foldout map of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, the setting for most of the Nobel laureate’s work. Faulkner sketched it out himself. Just to the east of the “Pine Hills” area and just north of the squiggly river that gives the place its name, he wrote, “William Faulkner, sole owner and proprietor.”

William Faulkner sketched out a map of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, at his publisher’s request. In this closeup, he identifies himself as the “sole owner and proprietor.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

William Faulkner sketched out a map of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, at his publisher’s request. In this closeup, he identifies himself as the “sole owner and proprietor.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.There’s also a brisk post-publication demand for maps that show readers where authors lived and worked, or the places in which their characters came to life. This begins with the foundations of Western literature — Odysseus’ epic 10-year trip home after the Trojan War — and continues today, more than 2,700 years later.Name a famous fictional work and there’s a map showing you the highlights — Count Dracula came this way, Mrs. Dalloway went shopping here, the Buendia family lived there, James Bond got in trouble in all these places.

In “The Phantom Tollbooth,” artist Jules Feiffer sketched out the Sea of Knowledge. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

In “The Phantom Tollbooth,” artist Jules Feiffer sketched out the Sea of Knowledge. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.This appeal isn’t hard to understand, says bestselling novelist Ace Atkins, who will receive the 2026 Harper Lee Award next year in his home state of Alabama.

Two decades ago, when he settled in Oxford, Mississippi, not far from Faulkner’s home, he had an idea for a series of books set in a fictional Mississippi county, similar to Faulkner’s. So, before he wrote a word of what turned out to be an 11-book series, he got a ruler, a manila folder, a glass of bourbon and started drawing a map of his new creation. Streets, stores, woods, the whole shebang. He included several shoutouts to Faulkner characters so readers would understand the homage.

“That’s the fun of it, just having a county like that and developing new rivers and creeks and places where events happened,” he said. “That map became much more alive as I continued to write the books.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 75 followers