Amanda Curtin's Blog

November 26, 2025

A new novel for 2026…

I’m thrilled to share the cover of Six Days, which is being published by Upswell in August 2026.

Daniel, an expatriate Australian who has lived in Paris for more than forty years, has made a mess of his life and is trying to atone, to become the ‘good man’ his friend Marcelline believes him to be. But Marcelline has disappeared, the quotidian world has been tipped out of balance and Daniel makes an error of judgment that places at risk everything he values.

More on the Upswell website.

November 23, 2025

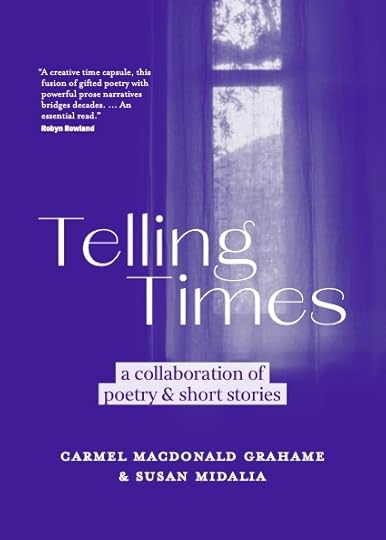

Telling Times

Telling Times

Carmel Macdonald Grahame & Susan Midalia

Short fiction/poetry

2025; see end of post for availability

It is a great pleasure to read anything written by Susan Midalia or Carmel Macdonald Grahame, so to find them together in a volume of their own is a rare treat. Telling Times is unusual in being a collaboration of two writers writing in two genres, with a common purpose.

I’ll let the book’s back-cover blurb elucidate this further:

From beauty pageants to experiences of war, Telling Times charts the lives of women and girls in the context of crucial events and political movements that have shaped the modern western world. Its ethical lens is trained on subjects as varied as education, migrant experience, domestic violence, the movie Titanic and the effects of contemporary technology. Acutely observed, and with a keen sense of social justice, Telling Times takes readers from the 1950s into the new millennium, where the plight of asylum seekers and awareness of climate change begin to shape a sense of our future.

Carmel Macdonald Grahame’s short fiction, poetry, critical essays and reviews have appeared in literary journals and anthologies in Australia and Canada, and her novel, Personal Effects, was published by UWAP in 2014. Her most recent publication is Angles, a poetry collaboration with Karen Throssell. Carmel currently lives in Victoria.

Susan Midalia is the author of three short story collections, all shortlisted for major national awards—A History of the Beanbag, An Unknown Sky and Feet to the Stars—as well as two novels, The Art of Persuasion and Everyday Madness. Her latest publication is Miniatures, a collection of flash fiction. Susan lives in Perth.

I was delighted when Susan and Carmel agreed to tackle a barrage of questions from me.

AC: For the benefit of those who have not had the pleasure of hearing the two of you speak about the genesis of Telling Times, could you please sketch out how this collaboration came into being?

CMG: Susan and I have been friends for years. When she sent an email suggesting we exchange work, we initially thought of it as a writerly exchange, an exercise if you like, for me during a protracted Melbourne lockdown. The invitation was a wonderful way of spending time that had begun to feel quite lost. As we exchanged work, the idea grew that we might make something of it; that our retrospections had a point to them. The structure grew out of our correspondence, through emails, phone calls and some face-to-face meetings, about this sense of the relevance of the work.

SM: As Carmel said, the collaboration was a way to help Carmel endure months of lockdown, but I was also in need of some stimulation and encouragement after months of not writing a thing. All writers have these fallow times, but I was feeling increasingly moody about my lack of productivity. So the collaboration helped both of us get into the swing of writing again and to keep refining our writerly and editing skills. And we’re still great friends after the process!

AC: The book is a bold, beautiful hybrid in terms of genre, combining Susan’s short stories and Carmel’s poems. I have a couple of questions regarding genre, the first for Carmel. When I first met you, many years ago, you were a prose writer. I remember your powerful short stories (I can vividly remember you reading one called ‘Slack Key Guitar’), and of course there is your beautiful novel, Personal Effects. Has there been a particular impetus for your turning towards poetry or was it just the right vehicle, for you, for this project?

CMG: I’ve always most enjoyed short forms and I find the short story a rich genre. It requires us to write economically into a situation, an experience, a relationship, and to find ways of opening it out internally to suggest circumstances beyond the story itself. It’s a writerly challenge I’ve always enjoyed trying to meet, deeply pleasurable in fact. Economy of form makes particular demands, doesn’t it? As does poetry of course, which is even more finely wrought in that you most often come to it with a preexisting sense of form. In both cases it has something to do with taking pleasure in the intricacies of the work. I think of it as a kind of embroidery. I enjoy the essay form for the same reason: there’s an internal logic you are hoping to stitch together in language. You are always finding the language to give expression to an idea, are you not? Was it Mallarmé who said poetry is made of words, not ideas—a favourite quote of mine—meaning that language is the stuff with which you’re working, your paint if you like. I wrote my novella as a personal challenge to see if I could bring the same sustained attention to creative work as I had previously applied to the writing of academic work, like writing a thesis. I wanted to try that deeper immersion into storytelling, but the sprawl of the form and the time it takes to achieve it are not for me. I’m a miniaturist, I guess.

AC: And Susan, I’ve never known you as a poet, although your prose is often undoubtedly poetic. Can you see yourself ever inhabiting that space?

SM: As you suggest, Amanda, the line between poetry and prose is porous. Both genres, at least in their modern forms, rely on compression, implication and concision. Both can have a narrative impulse, and both can use imagery, metaphor and the musicality of language. But on those few occasions when I’ve attempted to write poetry, it always read like chopped up prose: banal, predictable, dead. What draws me to prose is a fascination with the psychology of character (although the poetic form of the dramatic monologue is a study in the ambiguity and complexity of an individual). I enjoy imagining creating the inner lives and the voices of different characters, and not always sympathetic ones: individuals of different ages, genders, cultural backgrounds, temperaments and values. Although I’ve published two novels, my heart lies with the short story form, because it reminds me that we experience our life in terms of moments in time: a crisis, a turning point, a revelation, the realisation of intense disillusionment, a brief moment of unalloyed joy. I also love striving to combine economy and evocation, brevity and depth, in ways that I hope readers will find satisfying, and I’m drawn to the use of the unsaid—what cannot or must not be expressed—that often characterises short stories. It reminds us that life is always a contest between the spoken and the silent, the known and the unknown. It also encourages readers to read between the lines, as it were; to be active participants in the creation of meaning, instead of passive recipients.

AC: Telling Times uses decades (1950s–2000s) as its structuring/thematic logic, and I’ve heard you both say, quite forcefully, that its focus is not nostalgia; that it has, rather, an anti-nostalgia focus in the sense of questioning, critiquing, laying bare those times. For example, the title of the 1950s pieces, ‘The Good Old Days’, is used in a deeply ironic way, in stark contrast to the way that phrase is sometimes invoked by certain politicians and others wearing rose-tinted glasses. Tell us a little about some of the issues your pieces speak to.

CMG: Just to take two examples—It seems to me that a decade like the 1950s is often idealised, probably in the wake of World War II. In fact, when I scrutinise it, I come up with childhood memories of an often-cruel education system, unleashed child abuse, ugly prejudice against migrants who were arriving in great numbers, deep institutional misogyny, and a culture profoundly riven by sectarianism. I try to take a child-perspective of what I observed and experienced around me and to tell it as vividly, as true-to-life, as I can. This impulse is at work in poems like ‘Telling Times’ and ‘The Red Phone Box’. Later, in the 1980s say, a changing and unscrupulous workplace culture became evident as economic rationalism took hold. I engage with my memories of this in the poem ‘Zeitgeist’ that opens the decade. The AIDS crisis occurred during which homophobia and a self-evident lack of basic compassion in response gripped the world. Chernobyl and technologies of various kinds began to give us the sense of a threatened planet, President Reagan and his Star Wars defence not least. Retrospectively it felt to me like the decade when optimism waned in some global way.

Both the stories and poems are rich with details and features of each decade that we do celebrate, but the driving impulse was to resist nostalgia and keep track of what we saw as significant and sometimes disheartening changes. I suppose it amounts to a skewed form of memoir, and the collaboration and hybrid form allowed us to be comprehensive and agile in our retrospections.

SM: Like Carmel, I’ve used the perspective of children in the 1950s section of our book to expose the rigidity and cruelty of teachers; to reveal the racism and xenophobia of a period of history which white Australians still refer to as ‘the good old days’. A couple of the stories in that decade are heavily autobiographical: ‘Fitting In’ and ‘Dictation’ (although the latter is deliberately hyperbolic…I had no intention of being subtle!). The child’s perspective can be a particularly engaging one, combining as it often does raw emotion and a naivety about the actions and beliefs of the adult world. And while some of the details in the book about fashion, objects, food, will give older readers the pleasure of recognition, one of our specific aims was to undercut stereotyped and sometimes romanticised ideas about the past. As another example: the 1960s in Australia is still often viewed as socially and morally progressive: all that sex, drugs and rock and roll (alas, that wasn’t my experience as an adolescent). While the hippie culture was becoming more visible, the country was still in the tight grip of conservative forces. Rape within marriage was legal; abortion was illegal under any circumstances; male homosexuality was illegal; domestic violence was typically ignored by the police—regarded as a ‘personal’ matter between husbands and wives. And as some of Carmel’s later poems and my later stories suggest, while there undoubtedly has been some progress, prejudice and bigotry persist.

AC: The stories and poems have a distinctly Western Australian flavour, and many cultural references that will be especially satisfying for readers who live or have lived here. (My own favourite is the reference to the House of Tarvydas. How I longed, at fifteen, to be cool enough, or able to afford, or even to have an occasion I could wear, a Ruth Tarvydas dress!) What was your thinking in taking this approach?

CMG: My thinking was to pay attention to significant events and the flavours of each decade, to try to capture a kind of atmosphere that is particular to a place—it’s in the detail really. Tim Winton, Elizabeth Jolley, so many more, have firmly imprinted our local setting on the literary landscape. Western Australia continues to be my country, although as life has gone on, I’ve had to be mobile. I wanted to acknowledge historical circumstances that have been a part of my experience and tell it as I see it from that vantage point. Without fictionalising, and by weaving personal and observed circumstances together, I tried imaginatively to reinhabit the times and places in which I’ve lived. And for much of that time I lived in Fremantle. Heartland.

SM: I spent my first ten years living in seven different towns in the West Australian wheatbelt—my father was a salesman who was always in search of a ‘better’ job. I think the experience left me with a deep sense of dislocation; a feeling that I didn’t really ‘belong’ to any one place; a feeling exacerbated by being the child of postwar European migrants. I’ve tried to capture that sense of living in Western Australia in two stories set in the 1950s. What has always interested me as an adult living in Perth is Western Australia as a political, rather than a physical space. My natal family always talked politics, sometimes ferociously so (as in my story ‘Dirty Commie Bastards’), and I have continued to do so with my children and with friends. I wanted to capture the ‘flavour’ of some major events in my adult life: the passion of ideas, if you like. The Vietnam War, the AIDS crisis, the Lindy Chamberlain case, the Bicentennial celebrations, for example.

AC: Still on the subject of Western Australia: Carmel, I’m wondering what it was like to write about your former home from a geographical (as well as temporal) distance. Do you think it made any difference? Gave you a different perspective?

CMG: I do. Time and distance have made my sense of the where-and-when more comprehensive perhaps than would otherwise have been possible for me—the view from outside can be panoramic, so they say. I think writing about anywhere after you have left it somehow illuminates your experience of it. At the same time, since I have a sense of distilling personal experience and trying to blend it with things I have heard from other people, it was inevitable that my early focus would be WA. It anchors my thinking. I also wanted to celebrate Western Australia, to make it sing in parts of the country where it seems to me under-sung.

AC: Susan, if musicality is one characteristic of your prose, another is humour. How important is humour in this collection, and in your work generally?

SM: Humour in this collection is a vital part of the way I respond to the injustices and cruelties of the world. As Oscar Wilde famously quipped: ‘Comedy is the most serious form of literature.’ We laugh or give a wry smile, and then we think about why we’ve reacted in this way. Sometimes I’ve used satire—the deliberate use of exaggeration—as in my story ‘Dictation’ to expose the sadism of a teacher. The satiric story ‘Topical’ takes form of an interview in which a homophobic politician’s responses to questions become increasingly ludicrous, unhinged. I’ve also used techniques such as incongruity, juxtaposition and the form of a questionnaire to make fun of the Australian public’s warped priorities: for example, choosing Queen Elizabeth’s visit as more important than the return of Vietnam veterans. Apart from using humour for ethical and political purposes, I also wanted readers to have a laugh at the absurdities of life. If I believed in reincarnation, I would like to come back as a stand-up comedian (without the heckling). I can think of nothing more joyful than making a room full of people laugh.

AC: Carmel, while listening to you speak about the past, I was struck by your comment about belief: that in those earlier times in your life, you had the absolute belief that it was possible to change the world through activism, through alternative ways of living; that you were going to achieve it. The poem ‘Season’ (1970s) beautifully conveys that kind of optimism. I’m wondering what it was like to write that in hindsight.

CMG: To be honest it was partly driven by a sense of disappointment and a growing sense of disillusionment. I remember a time of confidence in ideas like answers blowing in the wind…It’s Time…Give Peace a chance…etc. We tried to create communes, live in alternative ways, send our children to alternative schools and so on. Protesters chained themselves to trees. There was a burgeoning environmental movement. Women’s refuges were set up in the hopes of finding solutions to misogyny and family violence. Refugees were welcomed after the Vietnam War. And so on. There was a sense of forward momentum, possibility, potential. There is a growing sense among many of my contemporaries of wheels being reinvented and old ground being gone over, of past efforts being dismissed rather than furthered (the old idea of standing on the shoulders of those who came before seems to have been ‘influenced’ out of existence), and above all peace most certainly has not been achieved. It feels now that a world we thought possible—so idealistically—has slipped below the horizon. Poems like ‘Of States, Of Mind’ and ‘Invasion Eve Protest’ are underpinned by this sense of disillusionment.

AC: Susan, I love the companion stories ‘And Here is the News for 2001’ and ‘And Here is the News for 2009’, which combine satire and serious comment in an unusual way. Could you talk, please, about the way you put these stories together?

SM: These two stories, which book-end the final decade of the collection, are fundamentally concerned with the inhumane treatment of asylum seekers and continuing inaction on climate change (both of which, to my despair, remain with us today). Both stories use the form of a news broadcast in which the seemingly endless repetition of headlines and soundbites about those two issues draws attention to the fact that politicians and the general public keep denying responsibility for addressing, let alone trying to resolve, the problems. Using the form of a news broadcast also allowed me to cover a whole range of other items: from the important, like the attack on the Twin Towers, to the trivial, like the popularity of distressed skinny jeans. It was a way of suggesting that the daily diet of news can ultimately reduce everything to the same value. I’ve also mixed fact and fiction to, for example, satirise misogyny: the then Deputy Prime Minister Julia Gillard being vilified as ‘deliberately barren’ (a real statement made by a conservative politician) and mocked for her new hairstyle being ‘too masculine’ (fictional). Another example is the announcement of the First Nations movie Samson and Delilah as the winner of the 2009 Australian Film Industry Awards (a fact), followed by an invented comment from a politician about most Australians being ‘fed up to the teeth with all this rubbish about so-called Indigenous so-called disadvantage’. I’m so glad you enjoyed these two stories, Amanda, because I feared that the barrage of lists might merely frustrate the reader, when part of my point was for them to experience the frustration of continuing injustice, bigotry and political self-interest.

AC: You have been quite open in talking about the lukewarm/non-existent response you received after submitting Telling Times to several publishers. The hybridity of the work counted against you, I’m sure. Can you tell us about the experience of self-publishing this work: the positives and negatives.

CMG: I have to be honest and acknowledge Susan’s energy and her skill which have brought us to this conclusion. We both have track records as readers and editors and do have genuine faith in each other’s work, and this gave us confidence that the book has something to offer. So I was only pleased to join a growing DIY Arts movement. Publishing independently is no longer tarnished by the vanity publishing label, for obvious reasons: the protocols of publishing work against us; a submission taking six months for a response or, regrettably, receiving none at all; and in the current underfunded climate, an experimental, mixed-genre text like ours is not going to be regarded as a commercial proposition. As well, many publishers insist that your work hasn’t been submitted elsewhere, so all this meant that we would simply run out of time to put our work out there. This is the subject of many conversations I have with poets who have long and substantial track records. And as some of them say about the current difficulties of getting published—just when we’d really learned the craft! The actual process of bringing this book to fruition has taught me a lot about the industry, and there is real satisfaction in taking creative responsibility for your work from first beginnings to having it in your hand. Perhaps the most positive part of the experience has been the fruitful collaboration between us, even about the nitty-gritty of publishing.

SM: While Carmel generously attributes the final production of this book to my energy and skill, I also have to say that she can be ridiculously modest about sending her work into the public domain. She would have left her exquisitely written novella languishing in a drawer if I hadn’t pushed her to send it to a publisher. But working on this project together has been a rewarding joint effort. We knew that finding a publisher would be difficult: neither poetry nor short stories are on top of publishers’ lists, and many publishers don’t accept either genre at all. So self-publishing it was. The positives of the process? Professional advice from Night Parrot Press enabled us to find a wonderful typesetter and printer, both of whom gave us choices typically unavailable from a publishing house. The typesetter gave us several options for the font and the layout, and he was perfectly happy for Carmel and me to keep making countless nitpicky changes with each draft, at no extra cost. The printer was also extremely accommodating about all stages of the process, while their in-house designer consulted with us about the cover, and gave us about 20 options! You rarely get that kind of flexibility with a traditional publisher. Self-publishing also allowed us to make changes at our own pace instead of having to adhere to a publisher’s deadline. Finally, we get to keep more of the proceeds from sales: a traditional publisher pays most writers a mere $2 per sale of a book! But there are of course negatives to the process, the two main ones being costs and marketing/distribution. The biggest costs were typesetting and printing, but there were also incidentals like postage and purchasing a bar code. We will now have to do all the marketing and distribution ourselves: it will be extremely time-consuming, and there’s no guarantee of a reward. As well, self-published works are ineligible for most literary awards. But despite all these obstacles, Carmel and I are delighted to be able to hold our book in our hands and to offer it to readers. We are proud of what we’ve created. Anyone interested in self-publishing is welcome to get in touch.

AC: And finally, and importantly, where can people buy the book? Will it be available also as an e-book? Audio-book?

CMG: We are selling it ourselves through readings and presentations. The Lane Bookshop in Claremont stocks copies of our book, and some libraries are accepting it. People can purchase a book by leaving a message on Susan’s website.

The book is also available on Amazon as a print-on-demand and as an e-book: check under the book’s title and the name of the authors. We know distribution is our next and biggest challenge, and we will take that on next year after the celebration of the launch winds down.

SM: Carmel and I will send a copy of the book to various independent bookshops, as well as preparing to brave face-to-face encounters with their managers. If readers enjoy the book, we would love them to use the power of word-of-mouth to promote it. Carmel and I would also welcome invitations from book clubs in Melbourne and Perth, respectively.

Telling Times was launched in Perth last month,

with a Melbourne launch to follow.

October 7, 2025

2, 2 and 2: David Whish-Wilson talks about O’Keefe

It’s been five years since I last posted in my ‘2, 2 and 2’ series featuring writers talking about specific aspects of their new books. I love hearing about those kernels of inspiration that lead a writer into a new work, and also about how their works connect with particular places. The third ‘2’ is different for each writer, and either the writer chooses something important to their work or I choose something I’m curious about.

Up to late 2020, I had featured 56 books. A chance reference to one of these posts recently made me think it’s time to revive the series.

David Whish-Wilson was my last guest, so it is entirely fitting that he should be the first now, and I’m delighted that he agreed!

David is an impressively prolific writer, having published eleven novels and three creative non-fiction titles while somehow also managing to teach creative writing at Curtin University in Perth and to create stunning-looking knives—this last possibly very handy for a crime writer! His crime novels have received two Ned Kelly Award shortlistings, and his last, Cutler, was shortlisted for the Danger Awards and the Western Australian Premier’s Book Awards.

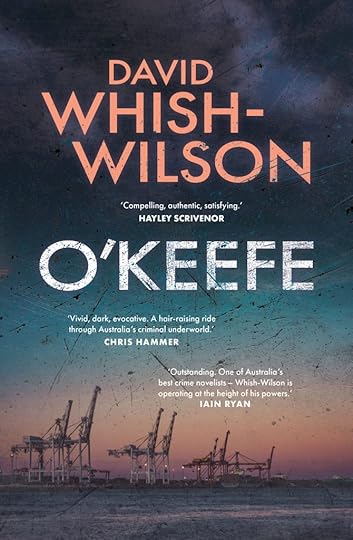

David’s new release, O’Keefe, is the second in his Undercover series (following on from Cutler). Here is the blurb:

Fresh from his exploits on the high seas, undercover operative Paul Cutler assumes a new identity to become Paul O’Keefe.

Paul is tasked with stepping into the shadows to reveal the mysteries surrounding a surge of Mexican cartel meth flooding Australian streets. Assigned to infiltrate a newly appointed security company at Fremantle Port, he discovers a clandestine world of off-the-books operations, and a business front that goes far beyond mere security. There’s a dangerous game afoot over who gets control of the port’s smuggling operations, and O’Keefe is caught in the crossfire.

A pulse-pounding thriller that takes a hard look at the Australian ‘cocaine gold rush’, where maritime crime meets the ruthless currents of the underworld.

Over to David…

2 things that inspired the novel

The first thing is that I wanted to follow on from the maritime theme of Cutler, which was set on the high seas amid the depredations of a modern industrial fishing vessel and all that entails. I greatly enjoyed writing Cutler, but because my protagonist was the only English speaker on board the vessel, it limited my enjoyment in terms of writing dialogue in the Australian vernacular, something I remedied by setting O’Keefe largely in Fremantle port, amid a mixed bunch of smugglers, local characters and policing officials.

What really inspired O’Keefe was coincidentally seeing an old friend from the Netherlands in a news bulletin following the murder of Holland’s best known journalist, Peter de Vries, in 2021. I was watching a late-night YouTube video about the murder and there was my friend, who I hadn’t seen for 30 years, distraught and grieving, a member of the public who’d gathered outside the journalist’s home. I became interested as a result in the pernicious influence cocaine money is having on Dutch and Belgian civil society, with the murders of lawyers and threats against politicians and judges, to the point that some have begun to label these two countries ‘narco-states’ (in the same vein as Mexico, Columbia, Ecuador, etc.). Given the high price of cocaine in Australia (the most expensive country in the world, bar two Middle East countries where drug possession carries the death penalty) and the fact that we’re per capita some of the largest users of cocaine in the world, I began to follow local events more closely, seeing some of the early warning signs of what has happened in countries like Holland, Belgium and parts of Spain and the Balkan states (where cocaine money brings violence, but also mass political corruption and the erosion of trust in civic institutions). I wrote O’Keefe as a way of situating that research in a local context, using examples of things that are on the public record as happening here already, and indicating the potential for some of the more serious things that have happened elsewhere.

2 places connected with the novel

This is probably my most Fremantle-centric book, despite the frequency of settings here in earlier Frank Swann and Lee Southern novels (and in some of my non-fiction). O’Keefe is a work of fiction, and there’s no suggestion that what I write about is actually happening now in the port (where I write, looking across at it), but I loved revisiting some of my favourite haunts in a contemporary context, when my earlier novels were all historical in some sense.

Even though what guided the setting of the story here was the port itself, the emotional momentum behind it was the awareness of the consequences that the so-called ‘war on drugs’ has meant for similar places, especially due to the extraordinary amounts of money generated by cocaine smuggling specifically, when large bribes can be offered without affecting the bottom line, when large amounts of money can be used to buy political influence without affecting the bottom line, and when well-funded violence is ruthlessly used to silence those who threaten business interests.

Two sobering thoughts

One quote contained in the book that really describes the way this particular branch of organised crime works is the terrible choice that people in positions of influence are forced to make between accepting either ‘the bribe or the bullet’. O’Keefe is written as a crime thriller, an entertainment for those who enjoy the genre, and designed to be enjoyed by anyone whether they’re interested in drug policy or not, but behind the thrills and spills is the reality of this quote for the characters in the story, but also sadly for many people caught up in the business reality of the world’s most lucrative recreational drug.

I highly recommend anyone interested in the failures of the war on drugs to read British journalist Johann Hari’s book Chasing the Scream. Treating drug addiction as a medical issue and decriminalising drug possession (such as in Portugal) will inevitably result in some degree of social harm; however, given the destabilisation of nation states caused by drug cartels and traffickers, the horrific violence associated with the international drug business, the overdose deaths and the incarceration of drug users and small-time dealers worldwide, the wastage of police resources and the fact that wherever there is prohibition there is organised crime, and wherever there is organised crime there is political and police corruption, it’s incredible to read in Hari’s text that the near universal prohibition on recreational drug use is the result of a single, troubled, moralistic, hypocritical and highly motivated American public servant, and that things could have so easily been so different.

O’Keefe is in stores now

Find out more at Fremantle Press

Follow David via his website or on Instagram

August 29, 2025

WA Premier’s Book Awards winners

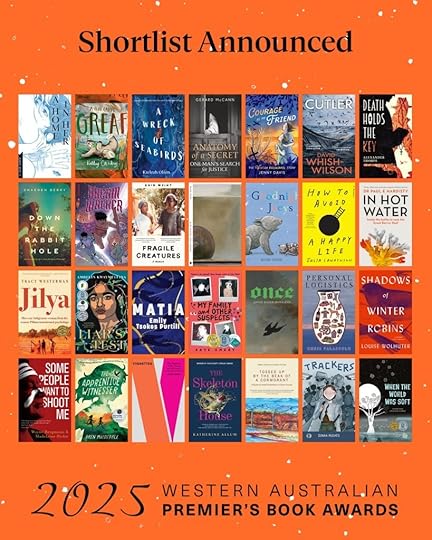

This year’s WA Premier’s Book Awards were celebrated tonight at the State Library of Western Australia. Congratulations to the winners—in bold below—as well as to all the shortlisted authors.

Emerging Writer

Down the Rabbit Hole by Shaeden BerryFragile Creatures: A Memoir by Khin MyintMatia by Emily Tsokos PurtillThe Skeleton House by Katherine AllumThe Moment of the Essay: Australian Letters and the Personal Essay by Daniel JuckesFiction Book of the Year

A Home in Her by Sarah Winifred SearleCutler by David Whish-WilsonDeath Holds the Key by Alexander ThorpeShadows of Winter Robins by Louise WolhuterOnce by Annie Raser-RowlandNon-Fiction Book of the Year

Anatomy of a Secret by Gerard McCannHow to Avoid a Happy Life by Julia LawrinsonSome People Want to Shoot Me by Wayne Bergmann & Madelaine DickieIn Hot Water: Inside the battle to save the Great Barrier Reef by Paul HardistyJilya by Tracy WestermanPoetry Book of the Year

Personal Logistics by Chris PalazzoloTossed Up by the Beak of a Cormorant by Nandi Chinna & Anne PoelinaG-d, Sleep, and Chaos by Alan FyfeChildren’s Book of the Year

A Leaf Called Greaf by Kelly CanbyGoodnight, Joeys by Renée TremlThe Apprentice Witnesser by Bren MacDibbleWhen the World Was Soft by Juluwarlu Group with Alex MankiewiczCourage be my Friend by Jenny DavisYoung Adult Book of the Year

A Wreck of Seabirds by Karleah OlsonLiar’s Test by Ambelin KwaymullinaMy Family and Other Suspects by Kate EmeryTrackers by Donna HughesDreamwalker #1 by Scott Wilson & Molly Hunt with Chris WoodDaisy Utemorrah Award for Unpublished Indigenous Junior and Young Adult Writing

Noble Intentions by Krista DunstanThe Takeback Heist by Jannali JonesJax Paperweight and the Neon Starway by Beau WindonThe Book of the Year Award, drawn from the winners and sponsored by Writing WA, was won by Alan Fyfe for G-d, Sleep, and Chaos.

Congratulations to all!

July 29, 2025

New writers’ festival for Fremantle

With the apparent demise of the Perth Writers’ Festival—for this year, anyway—it’s heartening to see new festivals emerge in Perth to fill the gap. Earlier in the year, there was Perth Storyfest 2025, established by The Writers Collective, which was fully booked and a great success. The second half of the year also sees the Festival of Fiction 2025, in Joondalup, running for its second year. And coming up very soon, a brand-new kind of writers’ festival in Fremantle/Walyalup, Totally Lit.

Totally Lit, which runs from 26 September to 10 October 2025, is said to be ‘inspired by place, culture, community and story’. I spoke to curator/producer Sharon Flindell about what the festival offers.

AC: It’s exciting news for Western Australia’s reading and writing community that there’s a new writers’ festival on the way, and I’m interested to know more about your plans to ‘shake up public expectations about what a writers’ festival can be’. Could you give me some examples?

SF: The idea for Totally Lit sprang from a personal light bulb moment I experienced a few years ago. I was attending the Literature Centre’s ‘Celebrate Reading’ Conference at Fremantle Town Hall and at some point I looked around the venue and noticed how many people in the audience and on stage were resident Fremantle writers and illustrators, the majority of whom were also published by Fremantle Press. Meanwhile, the team from Paper Bird were in the foyer busily selling books and it struck me that the whole event was this great collaboration between Fremantle’s writing sector organisations and writing talents. At that moment I realised Fremantle was truly a ‘city of literature’ and that this was something worth shouting about and celebrating. The festival sprang from there.

From the outset, I began thinking about curating a program of live literature events that didn’t rely solely on inviting audiences into auditoriums or focusing on new release titles and best-selling authors but that took Fremantle’s places and people and communities as the jumping off point.

What’s been so interesting and rewarding about developing Totally Lit has been the response from the community. The idea of Fremantle as a ‘city of literature’ has really resonated across the board—from local government to local businesses and of course writers and other creatives . There’s been a lot of enthusiasm to get involved, which has meant that we’ve also had lots of scope to invent new and fun ways to enjoy live literature and to think about creating events in unexpected places.

For seasoned writers’ festival audiences, Totally Lit has plenty of the types of events you would typically expect from a writers’ festival—book launches, open mic nights, workshops, great conversations with award-winning and best-selling authors, et al.—but we’ve also got quite a lot more.

Totally Lit is as much about oral storytelling as it is about the written word, so you can expect a range of different storytelling experiences and activities. You can also expect to discover Fremantle through its many stories, whether captured in places, buildings or books.

It’s all very much about having live lit fun in lots of different ways!

Unfortunately, we didn’t succeed in raising as much investment as we’d hoped, so there are several great events that we’d planned but aren’t going to be able to deliver this year. It’s ok, though, we’re keeping those in a back pocket for another time.

AC: When will the program be available, and who can we expect to see?

SF: Any day now!

We’re aiming to embrace a really broad range of communities, interests and age groups, and we’re really excited about the fantastic line-up of writers, storytellers and other creatives that have joined us in Totally Lit. We think we definitely have something for everyone.

AC: How can readers, writers and others in the literary industries become involved?

SF: Another way that we’re doing things a little differently at Totally Lit is that the program was always conceived to be a hybrid of curated and open access events. We wanted to create an inspiring framework and then open that out to allow more opportunities for others in the literary industries and wider community to create and bring their own events. We’ve had a strong response to that invitation and some fantastic events have been incorporated into the program as a result.

Once the program is launched, we hope there’ll be an equally strong response from the sector and that we’ll see lots of writers, publishers, readers, and others in the community who may not necessarily think of themselves as readers coming along to experience the festival. Perhaps we’ll change their ideas about what writers‘ festivals are and who they’re for.

AC: I see on your website that Fremantle/Walyalup is aiming to become Australia’s third UNESCO City of Literature (following Melbourne and Hobart). Is the festival involved with this?

SF: Establishing Fremantle/Walyalup as a UNESCO City of Literature and creating the Totally Lit festival were ideas born at the same time and as a result of the realisation that Fremantle truly is a city of literature. Both things we think should be recognised and celebrated.

Certainly in my various conversations over the past eighteen months, I believe there is a strong political and community will to do both.

Totally Lit is happening 26 September to 10 October 2025

The program is about to be announced. You can subscribe here for updates.

June 25, 2025

WA Premier’s Book Awards 2025

Congratulations to the amazing Western Australian authors and creators—and their publishers—shortlisted for this year’s WA Premier’s Book Awards! Winners in the following categories, together with the Book of the Year Award sponsored by Writing WA, will be announced in late August.

Emerging Writer

Down the Rabbit Hole by Shaeden BerryFragile Creatures: A Memoir by Khin MyintMatia by Emily Tsokos PurtillThe Skeleton House by Katherine AllumThe Moment of the Essay: Australian Letters and the Personal Essay by Daniel JuckesFiction Book of the Year

A Home in Her by Sarah Winifred SearleCutler by David Whish-WilsonDeath Holds the Key by Alexander ThorpeShadows of Winter Robins by Louise WolhuterOnce by Annie Raser-RowlandNon-Fiction Book of the Year

Anatomy of a Secret by Gerard McCannHow to Avoid a Happy Life by Julia LawrinsonSome People Want to Shoot Me by Wayne Bergmann & Madelaine DickieIn Hot Water: Inside the battle to save the Great Barrier Reef by Paul HardistyJilya by Tracy WestermanPoetry Book of the Year

Personal Logistics by Chris PalazzoloTossed Up by the Beak of a Cormorant by Nandi Chinna & Anne PoelinaG-d, Sleep, and Chaos by Alan FyfeChildren’s Book of the Year

A Leaf Called Greaf by Kelly CanbyGoodnight, Joeys by Renée TremlThe Apprentice Witnesser by Bren MacDibbleWhen the World Was Soft by Juluwarlu Group with Alex MankiewiczCourage be my Friend by Jenny DavisYoung Adult Book of the Year

A Wreck of Seabirds by Karleah OlsonLiar’s Test by Ambelin KwaymullinaMy Family and Other Suspects by Kate EmeryTrackers by Donna HughesDreamwalker #1 by Scott Wilson & Molly Hunt with Chris WoodDaisy Utemorrah Award for Unpublished Indigenous Junior and Young Adult Writing

Noble Intentions by Krista DunstanThe Takeback Heist by Jannali JonesJax Paperweight and the Neon Starway by Beau WindonJune 2, 2025

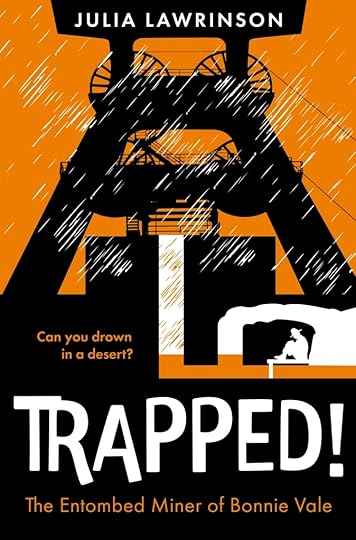

Talking (new) fiction: Julia Lawrinson’s Trapped!

I’m delighted to be featuring in this post one of my favourite Western Australian authors and another new book that celebrates Western Australian history. Julia Lawrinson’s Trapped!, a verse novel for middle readers, draws on an episode from the rich history of the Eastern Goldfields and is, I’m sure, destined to become a favourite with schools, libraries and young readers.

Julia is one of the most accomplished—and prolific—writers I know, and a truly impressive speaker. Her author biography only scratches the surface of her career, but here it is: She has published more than fifteen books for children and young people, from a picture book to books for older teenagers, and in 2024 published a memoir called How to Avoid a Happy Life [highly recommended]. Her books have been recognised in the Children’s Book Council Awards, the WA Premier’s Book Awards and the Queensland Literary Awards, and she has presented to schools across Australia, in Singapore and in Bali. She is an enthusiastic adult learner of Indonesian, yoga and the cello. Her favourite place on earth is the dog park.

The Julia Lawrinson section of my bookcase is huge!

In 1907, the mining town of Bonnie Vale experiences a sudden deluge of rain that floods a gold mine while miners are still at work down the shaft.

Joe’s dad is one of them. And it soon becomes clear that he’s the only one who hasn’t made it back out yet. Where is he? Why didn’t he escape with the others? And more importantly, how will they rescue him?

Inspired by the true story of the trapped miner of Bonnie Vale and told in verse, Julia Lawrinson weaves a tale that will beckon readers down into the gold mine with Joe’s dad to find out how the rescue unfolded.

Panel by panel

AC: Julia, we’ve both wandered through the rooms at the wonderful Exhibition Museum at Coolgardie. Was it there that you first heard about the incredible rescue that is at the heart of this new novel? I seem to remember that the museum has one room dedicated to the story.

JL: Yes, it was—I had absolutely no idea of it, and once I’d gone through the story, panel by panel, I couldn’t believe that it wasn’t better known outside the goldfields. At the end of the story, you turn on a light, and there is a life-size reconstruction of the rise, complete with Varischetti in it, which was completely arresting.

From thriving town…

AC: Bonnie Vale, where the novel is set, was a mining town about 15 kilometres north of Coolgardie. I say was because it appears on the map today as just the name of a mine site. What was the town like in 1907, when your novel is set?

JL: In the goldfields of 1907, the gold rush was on the wane but was still attracting prospectors from all over the world. Bonnie Vale was gazetted in 1897, and had twelve streets and about as many mining operations, of which the Westralia mine was the biggest. It had about 1,000 official inhabitants, but hundreds more—like Modesto ‘Charlie’ Varischetti—lived in tents, shanties made of flat tin cans and brush shelters. There was a state school with either one or two teachers, a hotel built of iron, a post office, and all the trades you could want in 1907: blacksmiths, carpenters, butchers, a baker, a tinsmith and a plumber. There was Australian Rules football, foot racing and weekend cricket, including a women’s team, and an 11 kilometre cycling track. A Catholic priest visited from Coolgardie once a month.

…to ghost town

AC: As someone fascinated by the ghost towns of the Eastern Goldfields, I’m wondering whether you were able to visit the site during your research and, if so, whether there is any remaining physical evidence of the township that once existed there?

JL: I really wanted to go. I applied for two grants but didn’t get them, so had to rely on photographs and descriptions. I had been to Kalgoorlie and Boulder many times, and Coolgardie twice, so I tried to extrapolate a bit. Apparently there is nothing there now, but I would have liked to have stood on the ground and felt it.

A young person’s voice

AC: Trapped! is told through the eyes of Joe, the eldest son of the trapped miner, Modesto Varischetti. Was there a real Joe?

JL: There was a Joe (Giovanni, not Guiseppe), but he was Modesto’s brother, not his son. Varischetti did have a twelve-year-old at the time he was trapped, but she was a girl, and in Italy with her four younger siblings. The story needed the point of view of a young person involved and invested in the rescue, and so Joe was created.

Changing approach

AC: I’m interested in your decision to write the story in the form of a verse novel, which is, I think, a first for you. Could you talk, please, about why you chose this form and the technical challenges and opportunities it presented?

JL: Initially I wrote the novel alternating between Joe’s point of view and third person. I ended up getting bogged in detail and research—about everything from the mine to the living conditions to the school routine and children’s games. In despair over this unwieldy manuscript, I decided to try and cut it down to the absolute nuts and bolts of the story. Before I knew it, I had a few experimental pages of verse. I sent it to Cate Sutherland at Fremantle Press, and she loved it, so I kept going. I was focusing on what it sounded like, reading it.

The appeal of verse

AC: The novel’s intended readership is middle readers, defined as age eight and over (although I think it could be read and enjoyed by anyone). Does the verse novel genre have specific appeal for this age group?

JL: I hope so! Kids can sometimes be overwhelmed by blocks of text, especially in this digital age, and I think poetry as a format is much friendlier.

Divisions

AC: Apart from being a thrilling narrative of a near-impossible rescue, Trapped! is also a very skilfully told story about social divisions: the Italians and the ‘Britishers’, the working men and the bosses. Some people might be surprised to learn that Italian immigration to Western Australia began this early. What were the circumstances that led to the migration of Italians to the other side of the world in these early years of the twentieth century, and what attitudes did they find here?

JL: The agricultural poverty of northern Italy led many Italians to move from working in lead or zinc mining in that area in the late 1800s to the goldfields for work, mostly with the aim of sending money home to their families. But the attitude they found from the labouring ‘Britishers’, or Australians of British descent, was often harsh. One woman who grew up in Bonnie Vale from 1899 and lived there until 1911 said the mines chose to employ the Italians as ‘cheap labour’. She remembered some Italians walking seven miles from the train line to the Westralia mine, but were chased off: her mother, who ran the hotel, hid them wherever she could, in the pantry and under the bed, and told the men chasing them to take it up with the mine managers, not the poor Italians.*

There were Royal Commissions in 1902 and 1904 into foreign contract workers, focusing mostly on Italians. Even though the commissions concluded there was no undercutting of wages, the tension remained. In 1934 there was a riot in Kalgoorlie, aimed at ‘Dingbat Flat’, which housed Italians, Slavs and other southern Europeans.

My step-Nonna came to Western Australia as a child in the 1930s, and for all her days she remembered the terrible treatment she got from the other children, who made fun of her accent and the food she ate. Her stories were the basis of Joe’s treatment in the novel.

I think readers now will be surprised at how acrimonious the relationship was between Italians and Anglo Australians. To me it shows that divisions—even ones that appear stubborn and intractable—can eventually be overcome in the right circumstances.

A story revivified

AC: Given the dramatic nature of the Bonnie Vale mine collapse and the rescue of Varischetti, one might imagine it would be a story known to most Western Australians. It certainly held the attention of the state, the country and even the world while it was happening. But are you finding this is the case?

JL: No, the story is remarkably unknown—hence this book! There is a quote from The West Australian from 29 March 1907 which says: ‘Our educational authorities would do well to find a place in the school reading books for so inspiring a story from real life.’ It’s taken more than a century, but I hope Trapped! is it!

*The woman was interviewed by Tom Austen for his book The Entombed Miner (St George Books, 1986).

Trapped! is published by Fremantle Press

Follow Julia on Substack; contact her via her website or Fremantle Press

March 31, 2025

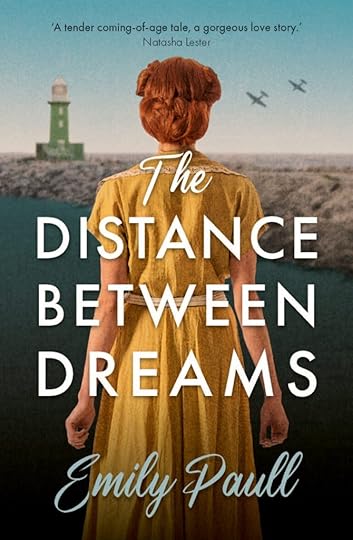

Talking (new) fiction: Emily Paull’s The Distance Between Dreams

I love history, and Western Australian history is a particular interest of mine, so I’m delighted to be featuring today a new historical novel that is set in Western Australia and focuses on major world events of the mid-twentieth century.

The Distance Between Dreams (Fremantle Press) is Emily Paull’s first novel, following her short story collection Well-Behaved Women (Margaret River Press, 2019). It was shortlisted for the 2023 Fogarty Literary Award, awarded biennially to a Western Australian author between 18 and 35 for an unpublished work of adult fiction. (*The Fogarty Award is currently open; the deadline for entries is 18 April 2025.)

Emily, a Western Australian writer and librarian, has also been shortlisted for the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Prize for Young Writers and the Stuart and Hadow Award. She is well known in the Perth writing community as an interviewer and reviewer, and her book reviews have been published in the Australian Book Review, AU Review and Westerly.

Seventeen years of drafts

Sarah Willis longs to free herself from the expectations of a privileged upbringing, while Winston Keller can’t afford the luxury of a dream. Despite their differences, the pair are drawn together in a whirlwind romance that defies the boundaries of class.

But when a dark family secret pulls the young lovers apart, and the Second World War plunges the world into chaos, it seems impossible that they will ever find their way back to each other—or even hold onto the dream of what might have been.

AC: Emily, I know that The Distance Between Dreams has had a very long gestation. How different is the novel we read today from the one you envisaged when you began?

EP: When I first started writing this book, I was 17 years old. I was studying for my final year of school before university, and one of my favourite subjects was history. I’d also just been on a trip to Japan—all of these things influenced elements of this book.

Initially I remember thinking that it was going to be a mystery of sorts, or a missing persons case set in the 1940s. In the original planning for the book, Winston was going to be trying to work out what had happened to Sarah, who he had met, had a whirlwind romance with, and who had then gone missing. But when I started writing, a completely different story came out!

I think the roots of the story as I envisaged it in 2008 are all still there, reflecting on class and family and secrets, but the layers that have been added since, as I have learned more and read more and got feedback from other writers, as well as working with some incredible editors, have added so much. I’m actually very grateful that it took 17 years to get published if this is the end result. It was worth it. (Though ask me again after I have seen some reviews…)

Wartime FremantleAC: I love that Western Australian history is front and centre in this novel, intersecting with world history and the history of individuals and families. How did you go about bringing to life Fremantle in the prewar and World War II period?

EP: I know a lot of readers have started to feel like war novels, and in particular World War II novels, are a bit overdone, but as someone who grew up in Western Australia, I felt like our history wasn’t really all that present in the novels that were available. We’ve had a couple of wonderful books published since then, and I’ve enjoyed reading how other writers have approached this period, but I really wanted to write a book that was like the ones I loved reading, but was set in a place that I knew.

Fremantle was the second biggest naval port in the world during WWII and the biggest was Pearl Harbour, so after December 1941, West Australians might have been feeling a little anxious, but the influx of American naval personnel who were stationed in Fremantle after March 1942 also meant that there was a lot of excitement. Australian women really only knew American men from what they saw in the movies, so is it any wonder that quite a few of them got swept off their feet—though not all of them would have had a happy ending to their love stories.

Aside from books, my biggest research tool was Trove, the online newspaper archive. This was really useful for looking at the daily papers, and wherever I mentioned a particular time period in my writing, I could go and look at what the characters might have been seeing in the news that day to give me an idea of what daily life might have been like, what they cared about, what their leisure options were, etc. Sometimes a newspaper article even gave me a new direction to explore and this occasionally turned into a scene.

Looking for meaning in sufferingAC: Part IV of the novel, which evokes the horrifying conditions of prisoners of war forced to clear the jungle for construction of the Thai–Burma Railway, must have been a challenge to write. What sources did you use, and (without getting into spoiler territory) how did your research impact on the story and your writing of it?

EP: This section is another reason why I am glad that the book is being published now, in the version that it is in, rather than in an earlier form. I knew that I wanted Winston to go away to war, but I originally had a time jump, where we didn’t get to see where he ended up or what happened to him, and reading it back, that always felt off to me. A very, very intelligent writer I was friends with was the first person to suggest to me that Winston might have ended up as a prisoner of war and encouraged me to do some research into the Thai–Burma railway. I read a lot of history books, but I also read some memoirs and biographies (a few self-published) about people who had been there or who had a similar experience, and the film The Railway Man came out at exactly the right time for me.

Hilariously, I remember when The Narrow Road to the Deep North came out, I was so upset because I thought that writing about this was going to be something that set me apart and then Richard Flanagan had come along and drawn attention to that part of history again so everyone would write about it. I wanted to hate that book, but I didn’t, I loved it so much, and I am excited to watch the TV show that’s out this year.

It was difficult to write, yes, but I also wanted Winston’s experience to be meaningful, rather than just be a whole section of him suffering and being ill-treated and getting sick for the sake of it. So, while there are some things in there (based on what I found in research) that are really awful, there are also moments of friendship and hope.

The creative selfAC: Could you talk, please, about the decision to make Winston an artist and Sarah an actor? What does creativity bring to the lives of these young characters?

EP: I can’t draw, so making Winston an artist was maybe a bit of wish fulfillment on my part there. I liked the idea that Winston has a very practical attitude to life, but that he feels almost compelled to create things. When things get too much and he needs to unwind, he can lose himself in drawing. He’s tall and strong but he’s also sensitive and artistic, which makes him a target for a group of young men who have been bullying him since his school days—boys who have discovered that money can’t buy talent.

Sarah’s acting was originally a bit of an affectation. She starts off not wanting to be an actress so much as she just wants to be famous and a lot of this is tied to the idea of her being almost starved for love. Her parents’ love is very superficial. But she finds that she’s good at being dramatic and funny and performing for people, and making her friends laugh, so she thinks, why not make it a career. It’s only when she actually starts working with a proper theatre group that she realises acting isn’t what she thought it was and that she truly does love it.

I used to love drama class at high school so I think I gave her a bit of my own love of acting too.

New roles, new horizonsAC: The plot brings the issues of gender and class to the fore. The word feminism existed in those years, but I doubt it would have been treated seriously, let alone respectfully, in Perth and Fremantle. In Sarah, you’ve constructed an interesting character of her time. Was it difficult to strike a balance between the Sarah who is a product of patriarchal dominance and the Sarah who is alive to an incipient feminism?

EP: That’s always the danger, isn’t it, as a modern woman writing women in earlier times? It’s nearly impossible not to give them too much of your own feminism…They might not have used the word often, but during both World Wars, women found themselves taking on new roles and finding capabilities as they had to keep things running on the home front, or as they became nurses or worked in roles in the military. I imagine it was really hard for them to go back to the way things were when men started to return and wanted their jobs back.

Sarah was a tough character to get right in general, because of how brash she can be and because of the way she puts on a persona to get through the world sometimes—deep down, she’s quite lonely at the beginning of the book. Early readers kept telling me that they didn’t understand why Winston liked her so much and I was really perplexed by that, but I think the contradiction you talk about is a big part of it. Sarah knows that the life her father is giving her is a good one and she is supposed to be grateful, but she also knows that there’s a lot wrong with her situation and she feels like she deserves more, she just doesn’t know how to get it. I had to revise her many, many, many times. But I also feel that any woman who has been told to tone it down, or that she’s too much, too loud, too dramatic etc. will relate to Sarah.

Contrary to what we’ve been told…AC: Did you know, from the beginning, that class would play such an integral role in your story? I ask because I’ve sometimes heard, or read, the comment that Australia has always been a ‘classless society’, which to my mind could not be further from the truth.

EP: That came up so often in my history classes, the idea of Australia being an egalitarian society, and it’s just not true. You just have to travel from one suburb to another to see it, even in relation to the older houses, the schools, the churches.

Yes, class was always integral to the tension in my book. Sarah’s father, Robert Willis, is from a farming background but he’s very proud of being a self-made man because he sold the farm and used it to start a business manufacturing and distributing cigarettes. I think part of the reason why Robert is so against the idea of Winston and Sarah being involved is that he sees her association with Winston as a kind of backslide to working-class status, and he thinks of that as shameful.

The difference in their classes also means that Sarah is able to imagine a lot of different possibilities for her future and have an idealised dream life in her head because money makes things more possible, whereas Winston has never even considered doing anything other than working in a factory and doing what he needs to do to make ends meet. It’s only when they meet and see the world through each other’s eyes that things begin to change for them.

Sleepers and dreamersAC: I always ask writers about the title of their work because I have had varying experiences with titles myself—ranging from ‘always was’ to ‘the book has to go the printer next week and still doesn’t have a title’! Where do you sit on that continuum with this book?

EP: I am not very good at titles! Originally the book was called The Compound because that is the name of the album that inspired it. Then after a few years I realised that didn’t really tell people much about the book and I workshopped all sorts of different ideas, coming up with Between the Sleepers. The idea of that was that sleepers meant railway sleepers but also the image of people sleeping, dreaming, and referenced Sarah’s feelings that Fremantle sometimes felt like a sleepy little town away from everything exciting. I still really love that title even though so many people have told me they don’t understand it!

When I entered this book in the Fogarty Literary Award in 2023, I knew that it had already been rejected by Fremantle Press I *think* twice by that point, and to give it the best shot I could, I needed to come up with a new title. Finally, I decided to go with The Dreamers.

The team at Fremantle Press came up with The Distance Between Dreams, and I liked the way they had elements of the two previous titles in there, but it did take me a while to warm up to it! Now that I’ve seen it printed on that beautiful cover, however, I can’t imagine it called anything else.

The Distance Between Dreams is published by Fremantle Press

Follow Emily on Facebook, Instagram, Substack and her website

Photo credit: author photograph by Jess Gately

December 31, 2024

And that was 2024…

Another year ends, and I can’t say it’s been the best I’ve had. But there are always highlights, and those are what I hope I’ll remember of 2024.

Ireland

Ireland has been a big part of my year. I finally made it to a many-times-delayed residency at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in County Monaghan, which was hugely productive creatively and pure joy personally. I also spent some time in the county town of Monaghan, where part of my work-in-progress is set, and driving around the Killeevan area with some wonderfully knowledgeable local taxi drivers. Along the way, I met several local historians who were generous with their time and knowledge.

I’ve read a lot of Irish fiction during the year, and it’s no surprise that Claire Keegan is once again among my favourites of the year. How good is So Late in the Day! An online residency run jointly by Varuna here and the Irish Writers Centre in Dublin introduced me to seven novelists, Irish and Australian, who are producing exciting new work and whose published work has blown me away.

Revered Irish novelist Edna O’Brien died this year, and I realised that, apart from a short story studied at university, I was unfamiliar with her work. So I embarked on the ‘Country Girls’ trilogy, novels that have also been categorised as memoirs: The Country Girls (1960), The Lonely Girl (1962) and Girls in their Married Bliss (1964) (this last title deeply ironic). I loved O’Brien’s portraits of ‘ordinary’ girls and young women and the city and rural social worlds of mid-twentieth century Ireland. O’Brien broke new ground in writing about matters of sex and the oppression of women, and these novels were considered so scandalous at the time that they were banned by clergy and the Irish Censorship Board.

And, finally, I’ve spent the year dwelling in the heart and mind of an Irish character whose voice I hope might find its way into print someday.

Vale Brenda Walker

I was deeply shocked and saddened by the recent death of WA novelist Brenda Walker—a terrible loss not only to her family, friends and colleagues but to the writing and reading community.

Brenda Walker’s many achievements as a writer included the historical novel The Wing of Night, one I have always admired for its focus on the women left behind when their men went to the Great War. Her other novels were Crush (debut, and winner of the TAG Hungerford Award), Poe’s Cat and One More River, and many writers are familiar with The Writer’s Reader: A Guide to Writing Fiction and Poetry, which she edited. Her memoir of a journey of recovery from breast cancer, Reading by Moonlight: How Books Saved a Life, won many awards.

For me, she was one of a group of women writers I looked up to from my earliest days as a reader of Western Australian literature, and whose work taught me much about writing and that there was value in women’s stories. Vale Brenda Walker.

Online…

One of the literary news stories of the year was Richard Flanagan winning, and declining, the $97,000 Baillie Gifford Prize for his non-fiction book Question 7: story here.

I was delighted to read that Gail Jones, one of my favourite authors, was granted the Creative Australia Award for Lifetime Achievement in Literature: story here.

I also listened to this excellent interview with Gail Jones, in which she talks about her award-winning novel Salonika Burning and imagining the past: link here.

A fabulous initiative by Australian authors, headed by Paddy O’Reilly, saw every Australian federal MP and senator gifted a ‘Summer Reading’ pack of five books that shed light on the complex history of the Israel–Gaza region. I’m planning to use the list of titles myself to help me understand the issues: story here.

And finally, I have been unable to do much in the way of blog posts this year, but I’m pleased to have featured an interview with WA author Katrina Kell on her fascinating historical novel Chloe, and the announcement of the winner of this year’s City of Fremantle Hungerford Award, Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes, whose bilingual hybrid-genre manuscript የተስፋ ፈተና / Trials of Hope will be published by Fremantle Press in 2025.

Happy New Year, everyone!

October 24, 2024

2024 Winner, City of Fremantle Hungerford Award

Warm congratulations to Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes, winner of the prestigious City of Fremantle Hungerford Award for 2024. Yirga’s memoir, የተስፋ ፈተና / Trials of Hope, is told in both poetry and prose, in English and Amharic (using Ethiopia’s indigenous script, Ge’ez Fidel), and follows his journey from boy shepherd in Ethiopia to human rights academic at Curtin University in Perth.

Yirga is a writer, researcher and poet from Lalibela, Ethiopia, who now lives in suburban Perth with his wife, writer Rebecca Higgie (award-winning author of the astoundingly imaginative The History of Mischief).

Yirga said:

The Hungerford Award means an opening of hope, a realisation that stories and languages like mine could have places in a world where they are rarely heard. People who live carrying multiple worlds shouldn’t have to hide or sacrifice one world to exist in the other world. This too is our home; our stories can be heard.

The City of Fremantle Hungerford Award is presented biennially for an unpublished manuscript by a Western Australian author, with a cash prize of $15,000, a publishing contract with Fremantle Press and, new this year, a residency fellowship with the Centre for Stories in Perth. In its thirty-three year history, the award has introduced many new writers who have gone on to establish stellar careers—among them, two of my all-time favourite writers, Gail Jones and Simone Lazaroo.

Congratulations must also go to the three other shortlisted authors for this year’s award: Howard McKenzie-Murray, Jodie Tes and Fiona Wilkes. Being shortlisted from a field of eighty manuscripts is no small achievement!

The award was judged by writers Richard Rossiter, Marcella Polain and Seth Malacari, and Fremantle Press publishers Georgia Richter and Cate Sutherland.