Gene Ruyle's Blog: Profile at Google+

April 8, 2018

This is the Link to my network site.

It finally brings ALL of my online sites together, including this one, into a single working network. From now on, I look forward to encountering everyone there.

Gene

(Update On The Newly Opened Site:)

In addition to this WP blog, ALL of my other sites have finally been combined into the one overarching site entitled, THE HUMAN REALM: The unfolding of human experience, which makes up an entire online network. It can be reached directly through http://www.thehumanrealm.com I now look forward to encountering you there. -Gene

December 29, 2013

ON THE UNACKNOWLEDGED DIFFICULTY OF BECOMING A PERSON

Is it really this hard? Yes. Then is it worth the trouble? You must consider the alternative and answer that for yourself. But why is it like this? Because most people decide to finish with life before life finishes with them. They start to drift, and gradually begin to sink from the weight of their own unspent vitality, until they come to settle in its residue. And if you decide not to do this, if you choose to take a stand that shows you will not join the hoards and herds of the half-alive, then you have made it clear that you will not go with them, that you will stand all by yourself if necessary, and that will threaten them -- and you will have exposed them too, and that will anger them, and they will see you as the enemy . . . and that is right. For if your way prevails, theirs will die. And if their way prevails, you will die. That is how it is and how it has always been. (from The Stuff of a Lifetime by Gene Ruyle)

March 2, 2013

#6 To Arrive At Something New

Making Your Way On To Anything New

Can you move further on by staying where you are? Are you likely to reach something new by searching in the familiar places and company of those who join in believing and behaving as you do? Should you perhaps start to search elsewhere . . . or at least in some significantly different way? And more important than these questions is this one: How, among the infinite number of ways there are of seeking, do you expect to be able to pick out the fruitful and most promising ones? There is only one clue I have and trust enough to pass along to anyone else: Look for someone who out-humans you – that can thus make your life bigger and turn it into something it never was before.

There are such furthering souls as these out there to be met. They already know what the basics are — such as what true friendship is, or how love is actually exchanged, and what life day in and day out really consists of — and you can tell right off that they live by these things because, of course, it shows. That is why, though neither they nor any human being can simply hand these to you, they can, if you’re willing to move, enable you to find your way on to all of them yourself.

If you are fortunate enough to come across a few such people and have this happen, they themselves may never even know they did this for you – (for most of us let just such deeply personal matters as this go unsaid) – but you will know and never forget either it or them. Were they to somehow learn this later, they’d likely simply give a little smile, turn, and be on their way. And isn’t this just the way it goes with love? Unfolding somewhere in its quickening way, unexpectedly showing itself here or there as it arises in a specific someone and something, a real piece of life and the world becoming better . . . ever growing itself into more of what it is, and then going its way . . . as it’s doing in places out there right now, just as it will be tomorrow, and keep on doing ever thereafter?

But all this can arise in one place only: in the “land of the living,” . . . there in those souls out there still seeking to arrive at something somewhere that is new.

December 1, 2012

The Arresting Life & Writings of Nikos Kazantzakis (an incidental review of his Report To Greco)

August 30, 2012

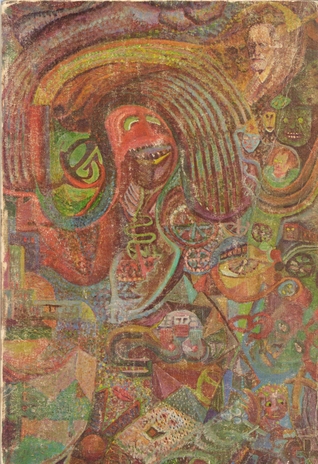

Gestalt Therapy In A Nutshell -- As Seen By Its Founder And Most Flamboyant Practitioner

In and Out the Garbage Pail

by Frederick S. Perls

From Fritz Perls himself comes this deceptively "simple," breezy, and brashly personal account in later life on how his work and thinking developed over time.

He sketches a broad-stroke portrait from his childhood in Berlin, Bar Mitzvah and puberty crisis ("I am a very bad boy and cause my parents plenty of trouble"), on through his military service in World War I, into the period that followed in Frankfurt during the time when the Institute for Social Research was being founded (sharing the same intellectual ethos of the neurological clinic in which Gestalt psychology was begun in earnest), up to his actual break in both theory and practice with Freud's traditional psychoanalytic method and circle, followed by his own subsequent individual development of Gestalt Therapy, starting in South Africa and then later carrying it to the United States, eventually landing him at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California -- which became the closest thing to a spiritual home he ever found.

Part autobiography, part theoretical elaboration and summing up, part off-the-cuff philosophizing and qualifying commentary, part painful personal admission, true confession, and a clearing of the air, part playful peacock parading and pleasurable pontificating of an iconic figure and public paragon, this work is woefully misunderstood and seriously distorted if it is either taken too lightly or made too much of. It must be seen in the context of all his other writings and serious work with clients, workshops led and lectures given, and ever-animated and sometimes slightly animalistic encounters (and he would be the first to admit when this was true -- as, indeed, he does in these pages) -- with the actual acquaintances, close friends, and yes, the enemies too, that made up the unusually rambunctious life that was his.

A member of my doctoral committee, Dr. Vincent F. O'Connell, then also teaching on the Psychiatric Faculty of the Medical School at the University of Florida, had heard Perls deliver the very first lecture on Gestalt Therapy ever given in the United States (attended by three people!). The two became close friends and collaborating colleagues from that point on until Perls's eventual death, March 14, 1970. "Vinnie" is referred to by Perls at a few places in this book. Among the many elaborations he shared with me about Perls's specific views on select topics -- always highly original, provocative, and enlightening -- was an intriguing one about Perls's having once written a paper entitled, "Interpretation is a hostile act." He was given to making such remarks. When working with the Human Development Institute in Atlanta, we filmed both Perls and Eric Berne in action before the American Psychological Association convention in San Francisco, near the end of their lives. Lamentably, these rich and revealing films on the two colorful figures were both withdrawn from circulation as part of a legal dispute and are no longer available for public or even private viewing. -G.R.)

(Cover painting: One of Perls's own entitled "Eyeglass in Gaza." If you look closely in the top right corner of this painting, you can plainly make out the famous face of Sigmund Freud. -G.R.)

August 29, 2012

What Turgenev’s Early Writing Led Him To

The Hunting Sketches , Book 1 (My Neighbour Radilov and Other Stories…) by Ivan Turgenev

A work from a distant country in a foreign language written over a century-and-a-half ago had better be able to speak for itself. Fortunately, as an audio book, this one can.

When a book first comes out, as this one did, it attracts or repels readers largely on the basis of three things: its author, its topic, and its type or genre. While a swing and a miss on any of these is a strike against you, a hit on just one of them may save the day and keep the game alive. When Turgenev published The Hunting Sketches in 1852, he wasn’t well known (Strike One!). What’s more, though his material had a definite place to it (the estate he had just inherited from his domineering mother) and a gaggle of colorful people, it really had no theme or topic (Strike Two!!). When it came to the sole remaining chance, what Turgenev did actually doubled his difficulty ratio, because what he chose wasn’t the familiar and more popular story form, but that of the sketch (When was the last time you read, and thoroughly enjoyed, a sketch – on anything?). And here is exactly where Turgenev’s fortunes pivoted and turned around. Not only did he get his hit, but he knocked the ball into the stands, and – to stick with the sports metaphor – he even made it into the hall of fame.

The response was instantaneous. It wasn’t a matter of beginners luck, but emerged out of what he chose to focus his sketches on: character. Not as a mere literary device or technique employed to make a written piece more effective (though many regard it in this very way, and their work shows it), and few writers succeed, despite their many labored attempts, in learning to wield it in the engaging and life-like way Turgenev did. That is what shows so clearly in The Hunting Sketches, where again and again he seizes his people with both hands, determined not to let them go until they all “gave,” handing over the revealing riches character always holds within. He wrote of this exclusively, relentlessly, and unswervingly in every single sketch. What Turgenev found in character gave the people he wrote about -- the peasants and nobles of the provincial Russia of his day -- real things to talk about, think of, feel, say, and do. And that is found in his distinctly vivid characters.

Surely this boundless depth and dimensionality came as something of a surprise even to him. For what had he published up to that time but a long poem and a short story? But in 1847 at 29, he begins to write in the fine fashion found in The Hunting Sketches. It changed both the way he saw things and the way he would write from then on. It even had a hand in changing the world around him (several credit his writing with hastening the official end of serfdom as well).

That Turgenev could actually see the reality of character is evidence of his artistic creativity, but that he also chose to follow where it led is a sure sign of his own.

Rainer Maria Rilke's Letters to a young poet, at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Rainer Maria Rilke's letters to a young poet, at the beginning of the twentieth century

In 1903, by choosing to answer a letter and some poems sent him by the nineteen-year-old Mr. Kappus, Rilke, then twenty-seven, initiated a five-year intermittent exchange of letters that became one of the most famous in world literature. The two began by acknowledging solitude as both a burden and a gift, but even more as the foundation without which no genuine poetic work could ever emerge -- this solitude being the center around which their letters and their lives revolved, and to which their thoughts returned again and again.

Both men wrote out of that particular reality each was facing and dealing with at the time: Kappus, revealing himself to another human being as never before, out of his considerable confusion and need for help; and Rilke, now with wife and child, starting to see for the first time how terribly great a distance was there both within and around him because of the individual at core he was. He feared this and longed to be freed of the suffering it brought; he even touches on that in these letters, but though he finally came to see the kind of relating it would take to transcend it, he could not manage to arrive there.

The powerful themes of creativity and love arise, and insights are expressed here regarding both of these that are as profound as can be found anywhere. As Pascal observed: "The ones we love the most are not those who give us something we did not have before, but those who show us the richness of what we already possess." That is certainly what Rilke was doing for Kappus: showing him the richness -- as well as the cost -- of fully acquiring that which he already possessed. And in doing that, Rilke was also speaking to himself as well.

What the two found is seen in what they wrote. Their efforts were rewarded. Will yours also be in reading of theirs? What you find will depend on whether you bring to the reading of their words the same fullness of living from your life that they brought to the writing about theirs. Yet, there's a way of getting some inkling of whether reading the book is likely prove to be worth your time. Try reading this:

"And if it frightens and torments you to think of childhood and of the simplicity and silence that accompanies it, because you can no longer believe in God, who appears in it everywhere, then ask yourself, dear Mr. Kappus, whether you have really lost God. Isn't it much truer to say that you have never yet possessed him? For when could that have been? Do you think that a child can hold him, him whom grown men bear only with great effort and whose weight crushes the old? Do you suppose that someone who really has him could lose him like a little stone? . . . But if you realize that he did not exist in your childhood, and did not exist previously, if you suspect that Christ was deluded by his yearning and Muhammad deceived by his pride -- and if you are terrified to feel that even now he does not exist, even at this moment when we are talking about him -- what justifies you then, if he never existed, in missing him like someone who has passed away and in searching for him as though he were lost?

"Why don't you think of him as the one who is coming, who has been approaching from all eternity, the one who will someday arrive . . . What keeps you from projecting his birth into the ages that are coming into existence, and living your life as a painful and lovely day in the history of a great pregnancy? Don't you see how everything that happens is again and again a beginning, and couldn't it be His beginning, since, in itself, starting is always so beautiful?"

Remember, this is only his prose. We've yet to cover the poetry that critics pro and con acknowledge extended the range of the whole German language, bringing forth melodies and a use of imagery in it not found there before. But if you find no such promise in a passage such as this, then I suggest you pass this book by and go on to other things that strike and stir you instead.

Of the numerous translations of Rilke's book into English, Stephen Mitchell's is the one I most prefer. For me, his comes closest to the common tongue, and has such a natural elegance to it that it lets Rilke's own shine through. Rilke's book speaks for itself, and Mitchell has the humility to let it. Enough said.

Harold Clurman -- The Completely Qualified Critic

The Collected Works of Harold Clurman by Marjorie Loggia

The Collected Works of Harold Clurman by Marjorie LoggiaMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

The Collected Works of Harold Clurman: Six Decades of Commentary on Theatre, Dance, Music, Film, Arts and Letters…

This book cannot be praised enough. Like the man from whom it came, it is too big, too magnificent, too extraordinary, too passionate, and too full of life to summarize. There is no way to do either it or him justice. The great English critic Kenneth Tynan came close: 'Few modern critics have traveled so far in search of theatre. Clurman gets to the heart of the matter more rapidly and more cogently than any other critic of his time. I don't think he's ever failed to recognize a new talent. You read Clurman to have your vision of the theatre replenished. If you're losing faith, you go and read Harold.'

But even that is much too thin and far too faint to do him justice. Clurman's place as one of the giants, not only in American theater but in the history of theater in the world, is unquestioned. If most theater critics could meet even three of Clurman's twelve "The Complete Critic's Qualifications," they would be twice the critics they are. I defy anyone to read a single page of this huge work (1055 pages), and not walk away from it with some fresh and significant discovery about the art and literature of our culture, the history of our country, or life in general. In reviewing this book, one critic said were he stranded on a desert isle in some ocean, and informed that the ship to rescue him had finally arrived, he would say "But First, I have to finish reading this book." Get you hands on the book in some store or library, take a good look at it, and you will see for yourself.

The book isn't about him, of course, but about all the grand classic arts presented in its title. Harold Clurman was born in 1901 and died in 1980. His offhand remarks and stories read like the Who's Who of American theater, to be sure, but his long life also reads like the What's What of American arts and literature. (There is no such book as the second, of course, but if there were, Clurman would likely have been the only one whose wealth of knowledge, first-hand involvement, demonstrated professional expertise, and widely acclaimed ability to write was broad enough, deep enough -- and yes, high and grand enough -- to find the right and truly telling words to fill its pages.)

Imagine, eighteen and in school at Columbia in New York, he skipped his classes one February afternoon to take in the first performance of a play just opening at the Morosco Theatre by a largely unknown thirty-one year old playwright. The play, Beyond The Horizon, by Eugene O'Neill. The point is, Clurman was there; as he also was when his father scraped together enough to send him to Paris to study at the Sorbonne from 1921-1924, where another student friend was on the way to becoming one of the favorite musical celebrities: Aaron Copland (they remained friends for life). Harold was there too, as he would be in numerous other places over the next sixty years at one incredible history-making event after another. With his eyes open, his passion aflame, his mind alert, and his pen always at hand. And he used it royally, and the 2,000 results of that are contained in this book, with a good many scattered elsewhere.

But let's bring this to a close by sharpening the focus and turning the spotlight on this man full force, listening to what another monumental figure, later to become a famous director of both stage and film, had to say about him. "He was the best first-week director of our time, as he was our best theater critic. What he did during that marvelous first week's work was to illuminate the play's theme, then sketch each role brilliantly, defining its place in building the final meaning of the production. . . .He had a unique way of talking to actors -- I didn't have it and I never heard of another director who did; he turned them on with his intellect, his analyses, and his insights. But also by his high spirits. Harold's work was joyous. He didn't hector his actors from an authoritarian position; he was a partner, not an overlord, in the struggle of production. He'd reveal to each actor at the onset a concept of his or her performance, one the actor could not have anticipated and could not have found on his own. Harold's visions were brilliant; actors were eager to realize them. His character descriptions were full of details, of stage "business." They were also full of compassion for the characters' dilemmas, their failings and their aspirations. . . .I used to read the notes he made in the margin of his text and to write down what he said to the actors after each rehearsal." (These are the words of Elia Kazan, taken from his autobiography, A Life.)

That's an indication of the richness to be found in the work and writings of Harold Clurman. And the marvel of the material is this: it is written with so much obvious underlying humanity, that even the untrained person can grasp the greater part of everything it says. That is an essential aspect of the wide-ranging greatness of this gifted man.

View all my reviews

August 28, 2012

Wandering The Wilderness Until The Desert Blooms

Artificial Wilderness by Sven Birkerts

Artificial Wilderness by Sven BirkertsMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

An Artificial Wilderness: Essays on 20th-Century Literature (William Morrow and Company, New Yourk, 1987)

Wandering The Wilderness Until The Desert Blooms

This book by Sven Birkerts -- whose fine essays have appeared in The New Republic, The New York Review of Books, and elsewhere -- just may serve to keep alive the fine art of literary criticism after the ravages of a post-modernism that has all but torn it apart. If this seems too harsh a verdict to render on the bleak outcomes to which elite intellectual efforts can all too easily lead, then please think again. Well before An Artificial Wilderness ever appeared, John Bayley's had this to say in New York Review of Books in June 4, 1981. "The reality of the thing, the return of the thing. Structuralism and deconstruction . . . have banished physical realities from literature, replacing them with the abstract play of language, the game of the signifiers. They were on their way out anyway, they were leaving literature, and the critical process, as usual, found ways of explaining and rationalizing their departure, even of suggesting they had never been there."

Enter Sven Birkerts. He had been quietly "worrying the matter" of his voluminous reading since his days as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, when he stumbled into a second-hand bookstore as well as upon the life-lasting pursuit that later led him to the proliferating gleanings infused into this bountiful book. But how to lay out the scatter of it all in "a single balanced entity," or better still, in some "more concrete narrative"? Avoiding the trap of trying to survey the entire span of a century, Birkerts wisely chose here instead to excavate the sites of some of its better-known prospectors in order to assay their findings -- thus dealing in substance instead of sweep. What he finds is high-grade ore. Since Birkerts has to fend off his share of sharpshooting detractors sniping at him from the hills', who take him to task for being much too fond of foreign writers over those from America's own shores, let us pick an American writer to enter as evidence and make our case. Birkerts, who clearly understands that it takes a soul to sense the sickness, lostness, or absence of another one, excavates Malcolm Lowry's overwhelming achievement Under the Volcano, rightly recognized the world over as a masterpiece in depicting nothing less than the ruin of a soul -- which in his own life, Lowry certainly lived out. No empty, arid, condescending, ivory-tower, vacuous, stuffy theorizing here. Every phrase is taut as a drawn bow string and terribly telling . . . Birkerts's no less than Lowry's. But don't take my word for it. Read this book and judge for yourself.

Because of how subtly his own mind works, Birkerts is also able to discern the subtlety that is there in the artful minds of those he is treating. This, in its turn, is what can bring forth in even the most barren wilderness a bloom in the desert as rare as this.

View all my reviews

Profile at Google+

plus.google.com/+GeneRuyle/posts

-G.R. My site at Google+ for stand-alone media clips that speak for themselves . . . and are designed for each viewer to quietly see, feel, and take in by themselves.

plus.google.com/+GeneRuyle/posts

-G.R. ...more

- Gene Ruyle's profile

- 5 followers