Phil Miller's Blog

April 5, 2016

Pitch In — Where?

No, I’m not talking about human vandals. It’s the bear, raccoon, or turkey vulture that would make a mess of the trash.

The “Adopt-a-Mile” sign on the county road features a cartoon figure dropping a wrapper into a trash can. It says, “Do Your Part, Pitch In.” If you think this sign literally lets drivers and their passengers know what to do with their litter, guess again.

Some of them don’t read the words on the city’s “Don’t be a Litterbug” notice but see the cartoon and follow the example, which wasn’t the artist’s intention, I’m sure.

Drive up and down the mile my wife and I have adopted, or the mile below, or the mile beyond, three “adopted” miles in a row, and you won’t see anything resembling a trash can within reach. Same thing applies to other county roads.

Why there aren’t trash cans placed every mile or so? I don’t need to ask the County Commissioners. The reason isn’t merely their lack of funds to pay for the hardware. It’s more than the lack of time for county road crews to come along to empty the cans every few days.

Even if the county planted a can every mile or two, unless they anchored it firmly to the ground and used a screw-on lid (not very practical for drive-by trash drops), our neighbors would pull out the trash and spread it around scavenging for anything edible or delectable.

No, I’m not talking about human vandals. It’s the bear, raccoon, or turkey vulture that would make a mess of the trash.

Which leaves us with signs instructing travelers to “pitch in” their litter but nowhere to pitch it. No wonder so many people just toss their cups, cans, bottles, napkins, and wrappers onto the road.

But wait! If people in a car or truck can endure keeping litter inside their vehicle until arriving at their destination, they will find trash cans at a gas station, in front of a retail store or doctor’s office, and in most cases, even at home.

But wait! If people in a car or truck can endure keeping litter inside their vehicle until arriving at their destination, they will find trash cans at a gas station, in front of a retail store or doctor’s office, and in most cases, even at home.So “Do Your Part — Pitch In,” after you get to the place where you can find a trash container. (Spread the word, okay?)

March 28, 2016

Choked by Styrofoam

So what are you supposed to do with it? Toss it out the car window?

Found this paper plate by the road today, only it’s not paper.

Ah, Styrofoam! For 75 years, it has kept pipes warm, coffee hot, and iced drinks cold. Now they mold it into hinged boxes called clam shells to hold a sandwich or a to-go meal.

How did people live without it?

When I directed a meals-on-wheels program, we searched for a suitable container to get a hot lunch from our kitchen to a client’s home. The problem with Styrofoam was, if someone saved the lunch until suppertime and tried to heat it up in a microwave, the package would melt. Worse still, it would leak toxic chemicals into their food. We found a safer alternative. However, Styrofoam cups and boxes are ever-present in our fast-food society.

You can’t take Styrofoam to the recycle center. It can’t be recycled. So what are you supposed to do with it? Toss it out the car window?

My mountain neighbors adopted the mile of road heading west from our mailbox. Since adopting the mile heading in the opposite direction, my wife and I share stories with our neighbors about the quest for a beautiful roadway.

“What gets me,” my friend says, “is the Styrofoam.”

“Agreed,” I say. “It breaks up into little pieces that are hard to pick up.”

We try to get the beverage cups and clamshell sandwich boxes before they break up, but the regular litterbugs keep us busy.

Since Styrofoam doesn’t rot away, it adds up. It takes hundreds of years to decompose — even if it breaks into little pieces. Those little pieces, by the way, choke animals that who smell the residue of our food and try to eat the container or its remnants.

If you care about wildlife, and if you care how the foothills look, please get that Styrofoam cup or box into a proper trash bag.

Better yet, patronize merchants who have opted not to use Styrofoam containers. Now that some cities are considering banning such products, safer alternatives are readily available.

March 21, 2016

Valleys of Dry Bones

In the midst of the valley, it is full of bones, and behold, there are very many upon the valley, and lo, they are very dry.

Spring waxes green, and I hold back. Less trekking down the steep slopes that fall eastward from the serpentine county road. During past summers, I’ve given in to the litterbugs, somewhat. I’ve put off picking up bottles or cans half-covered in poison ivy. I’ve left paper plates in a ditch if they could be sitting over a snake nest. I’ve even avoided wading into hip-high grass if I’m afraid I’ll exit with ticks and chiggers up my pants.

During winter’s final days, however, I’ve continued sliding down to clean up trash that has blown, washed, or been tossed over the edge.

A basic technique for identifying what doesn’t belong on the forest floor or valley wall is picking out contrasts. Granted, some clam shell meal boxes are black, but for the most part, the glint of aluminum, the sheen of plastic, and the bright whiteness of paper or Styrofoam give away my targets. Repetition trains my eyes, legs, and hands to head for the litter.

Litterbugs don’t hide their trash, but the forest does its best to camouflage what doesn’t belong there. Nature’s cover-up results in my half stumbling over a wine bottle buried under pine needles. It leads to my finding a large Styrofoam cup mostly concealed under a leafy fallen oak branch. I see half an inch of white! And pull forth a paper plate. Ta-dah!

Nature must silently laugh when I am deceived. I bend my knees and my back to reach down for what appears to be a corner of Styrofoam and — surprise!

In the midst of the valley, it is full of bones, and behold, there are very many upon the valley, and lo, they are very dry.

Sounds almost biblical. I’m not describing a religious experience, though. At least, I don’t think so. It’s not a mystical vision. I don’t feel called to prophesy to these bones. I’m merely surprised to see them.

Sometimes it’s a strand of vertebrae; from what creature, who  can say? Sometimes a longish leg bone, probably a deer though I wonder how long a wild turkey leg can be?

can say? Sometimes a longish leg bone, probably a deer though I wonder how long a wild turkey leg can be?

Often it’s a jawbone. Samson, as you know, slew thousands with a jawbone. What died under the grasp of these jaws before they died under some greater force?

This valley of dry bones doesn’t freak me out. Bones are Nature’s litter, and it’s not my job to haul Nature’s litter out of the valley.

This valley of dry bones doesn’t freak me out. Bones are Nature’s litter, and it’s not my job to haul Nature’s litter out of the valley.

Like the trees that break and fall on the valley floor in a storm, the bones provide a healthy reminder of mortality.

State laws prohibit letting our bones dry in the open after we die. If a human skeleton weren’t a sign of an unsolved mystery, and if I didn’t have to watch the disappearance of the flesh, I’d kneel in homage before the bones of the men and women astonishing me from beneath the leaves.

March 14, 2016

The Last Straw

How long until I can say I’ve picked up the last straw?

How many suckers live in our county? Of 28,000 residents, plus some-timers, how many get a drink with a plastic tube to suck on? Couple of thousand a day?

Of those thousand or two, how many get past the drive-through window, past the fast food exit, onto the four-lane and up one of our 256 miles of paved county roads? Safe to guess 500?

Of those 500 straws, how many end up on the side of the road? I find 5 or 10 a day just on the one mile of road my wife and I have adopted. That would average out to over 1200 a day if every mile gets that much litter! Hmm.

How long until I can say I’ve picked up the last straw?

Predictably, drivers don’t like to slosh beverages onto their laps. Gripping the wheel with their left hand, they hold a lid-covered cup in their right as they suck on their drink. Heaven smiles on those who keep the cup, lid, and straw until they can drop these into a trash can, but others use the roadside and forest floor as their garbage bin.

Plastic straws and lids take years to decompose. Sure, they crack and splinter in freezing weather, but they don’t dissolve. They collect by the roadside, down the hillside, half covered with leaves or mud, until a bird mistakes a straw for a worm and gets plastic splinters stuck in its craw.

I’ve heard sucking on plastic (with its BPA chemicals) isn’t even healthy for human beings. So here’s a pitch to restaurants, especially fast-food businesses. Give straws only at the customer’s request. Meanwhile, follow the lead of Texas Roadhouse and other establishments that have switched to paper or bamboo straws.

As a customer, consider carrying your own reusable sippy cup or a stainless steel or titanium straw, something you don’t have to put in the landfill. You’re not likely to throw an investment like that on the road, are you?

March 7, 2016

Butt Eaters

Even a raccoon deserves a better diet than cigarette butts.

One afternoon, I came across a spot where a driver emptied an entire ashtray full of cigarette butts on the road. I brought over my broom and dustpan and swept up 789 smelly butts, or thereabouts.

People refer to it as the “end” of the cigarette. They don’t even call it a “stub.” They call it like it is — a “butt.” Makes sense! After all, examined closely, a cigarette butt is downright ugly. Plus, for a while at least, it stinks.

Fifty years ago, lots of people smoked. They smoked indoors, in offices, college classrooms, airplanes, even hospital rooms. Place after place banned indoor smoking. Outside to a building entrance we pass by the free-standing outdoor ash urn, where smokers are instructed to dispose of the remnants of their cigarettes or cigars.

Some people still smoke indoors, though, in the privacy of their own homes — and cars or trucks. With our wet climate, most smokers aren’t worried about starting a forest fire when they flick their butt out the car window. Chances are, they’ve grown up watching other people do this. They think it’s normal and acceptable. Maybe they bought a car without an ash tray. Maybe their car’s ash tray is full. Or maybe they don’t like to stink up their car so they don’t use its ash tray.

According to one study, tobacco products comprise 38 percent of roadside litter. Animals can mistake these stubs for food. Even a raccoon deserves a better diet than cigarette butts.

Most smokers choose filtered cigarettes. The filters are made of cellulose acetate, a type of plastic which takes a long time to decompose. So their butts pile up and spoil the beauty of our mountain forests.

I doubt if the chamber of commerce wants to invite visitors to come see our stinky butts.

February 29, 2016

Recycling Tobacco Spit

“What’s your problem?” he griped. “I didn’t throw it on your property.”

Sometimes I picture myself returning home from a litter hike, laying out a bagful of trash on the driveway, washing the bottles, searching for cardboard that isn’t greasy, and separating the aluminum cans to salvage what’s recyclable.

We keep a bin outside our back door for glass, plastic, cardboard, paper and steel. We save plastic bags to re-use or recycle, too. I believe in recycling. It conserves natural resources and cuts down on the waste in landfills. Maybe I could add cans and bottles I find in ditches or on the hillside.

Collecting the litter seems a big enough job, though. Sorting glass, plastic, cardboard, and paper items would take even more time.

The recycling center limits plastic items to those  labeled with a 1 or a 2; it’s hard to see the number on some of the things I pick up. In the switchback coves of our mountain road, I zigzag up and down steep slopes. I reach through brambles, briars, prickles, and thorns for a Styrofoam coffee cup or half-empty beer can. It’s impractical to carry multiple bags for sorting. They snag and tear as it is.

labeled with a 1 or a 2; it’s hard to see the number on some of the things I pick up. In the switchback coves of our mountain road, I zigzag up and down steep slopes. I reach through brambles, briars, prickles, and thorns for a Styrofoam coffee cup or half-empty beer can. It’s impractical to carry multiple bags for sorting. They snag and tear as it is.

Besides, melted cheese coats cardboard pizza boxes. Grease from French fries soaks paper wrappers. Mud settles in glass bottles, and plastic bottles carry someone’s tobacco spit. So I’m pretty much resigned to mixing items which might have been recycled with the Styrofoam, cheap plastic and plain old garbage I send to the landfill.

At our recycling center, we can separate aluminum cans as a funding resource for the fire department. The department could get rich off the cans tossed into the woods and left half covered by oak leaves.

But do you know why so many cans never make it to the recycling center? Here’s a for instance. My friend gave a ride to a logger who had cut some trees on her land. As she drove him back to town after his day of work, the man refreshed himself with a can of beer. Yeah, open container in a moving vehicle, not uncommon in these parts. He chugged down his drink and tossed the can out the window of her truck.

“Hey!” she said. “Don’t throw cans out my window!”

“What’s your problem?” he griped. “I didn’t throw it on your property.”

Well, actually, if his trash lands on a county road or a state highway, it is our property, isn’t it?

February 22, 2016

An Unplanned Afternoon

. . . from the arched branches of a wild rose bush, a copper-colored can winked at me.

As the adoptive parent of a stretch of road, I employ two strategies. First, when possible while driving, if I see a cup, can, bottle, or sack cluttering the roadside, I park where the shoulder widens and run back to pick up the litter. Second, if time and weather permit, I hike along the road as it switches back and forth and down into the steep coves. On foot I find litter my eyes never see. Either way, unplanned adventures sometimes take me by surprise.

Early one afternoon, less than a mile from our cabin, I turned off Bullen Gap at Rosewood. Our mailbox is on the corner. On my left, ten yards up the one-lane road, from the arched branches of a wild rose bush, a copper-colored can winked at me. I stopped and shut off my motor. I hopped out and stared at the shiny object. Technically, it wasn’t within the boundaries of our adopted mile. Nevertheless, it was a place we pass every time we go anywhere, and it had been ignored since 1950, or so it seemed.

Taking a deep breath, I resolved to grope my way into the briar patch and get rid of the can.

Ultimately, I took possession of my target. But only after an hour and a half of tromping back and forth through bloodying blackberries and rose thorns, head-bumping low-hanging branches, and shin-skinning roots. Yes, all this to retrieve innumerable beer bottles, propane canisters, empty jars, aluminum cans, Styrofoam cups and clamshells, a window visor, a defunct 35-foot measuring tape, a nylon hiking boot, a jogging shoe, a child’s booster seat, a broken tea pot, a car’s headlamp, plastic beverage containers and margarine tubs.

Ultimately, I took possession of my target. But only after an hour and a half of tromping back and forth through bloodying blackberries and rose thorns, head-bumping low-hanging branches, and shin-skinning roots. Yes, all this to retrieve innumerable beer bottles, propane canisters, empty jars, aluminum cans, Styrofoam cups and clamshells, a window visor, a defunct 35-foot measuring tape, a nylon hiking boot, a jogging shoe, a child’s booster seat, a broken tea pot, a car’s headlamp, plastic beverage containers and margarine tubs.

These filled two large white trash bags. Stuffed them too full, let me add. The first one I set on a sheet of cellophane in the back seat. I hauled the second one around to the right side. Shards of glass tore holes in the bag. Putrid brown fluids sullied my upholstery. Off we hurried, the bags and I, to the road department’s dumpster.

The backseat bag I heaved over the seven-foot wall of the bin. The leaky one, however, hit the upper edge like a basketball bouncing off the rim.

The backseat bag I heaved over the seven-foot wall of the bin. The leaky one,  however, hit the upper edge like a basketball bouncing off the rim. It crashed and splashed shattered glass around my ankles. Not having planned to delve into such an undertaking, I’d neglected to wear my work gloves among the prickles and thorns. My hands were bloodied. So I was sure to put them on while scooping up the broken glass and dividing the spilled mess into two fresh bags.

however, hit the upper edge like a basketball bouncing off the rim. It crashed and splashed shattered glass around my ankles. Not having planned to delve into such an undertaking, I’d neglected to wear my work gloves among the prickles and thorns. My hands were bloodied. So I was sure to put them on while scooping up the broken glass and dividing the spilled mess into two fresh bags.

As for the muddy booster chair, I tossed it over the top without a bag. How old must the baby who once sat in it be by now?

February 15, 2016

The Murder of Crows

Seven black feathers still lay on the ground. Reverently, I positioned them next to the empty box.

In my thoughts, I commended the County Road Department. Two hours earlier, I had stopped there to report what I had come across.

“Y’all pick up road kill?” I asked.

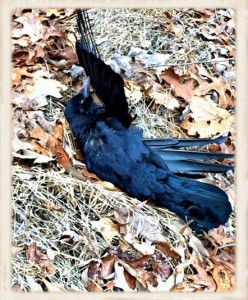

“Well, I was driving down road my wife and I adopted. I thought I saw a shredded black trash bag. I pulled over to check it out. One piece seemed hung up in a low branch of a tree. It was no trash bag. It was 21 dead crows. One was what I’d seen hanging from the branch.”

“How far from the road?” he asked, as if to imply he wasn’t about to send a crew down into the valley to pick up dead birds.

“Close enough to see from your car, maybe 10 feet from the shoulder. I’m afraid they’ll become a biohazard unless they’re removed.”

“Where about is this? Like from Sugar Creek, how far, which side?”

“Mile and a half, on your right,” I answered. “You’ll see an empty box of Remington shotgun shells with the crows.”

I had to take care of some paperwork when I got home. Also, I made a sandwich, but as soon as I could, I headed back with my camera to where I’d seen the crows. I remembered someone had painted a blue spot on a nearby tree. I pulled my car onto the shoulder and got out to look. The birds were gone. Only the empty box of shotgun shells called “Game Loads” remained. And the seven feathers.

As I picked up the box for my trash bag, I recalled telling the man at the road department, “Someone must’ve waited to watch them roost in their nest for the night and then let loose with the shotgun.”

I told a friend, “It’s hard for me not feel judgmental toward  whoever killed those crows. They’re intelligent birds, remarkable creatures. They weren’t near any corn fields. They weren’t causing any trouble. They were in a nest high up in a tree next to an uninhabited section of the road. They were settling in to keep each other warm through a cold night.”

whoever killed those crows. They’re intelligent birds, remarkable creatures. They weren’t near any corn fields. They weren’t causing any trouble. They were in a nest high up in a tree next to an uninhabited section of the road. They were settling in to keep each other warm through a cold night.”

My friend cried, “Where’s the sport in that? It’s like shooting fish in a barrel!”

Or, I thought, like lining people up against a wall for the firing squad.

Nevertheless, as I work at not seeing the speck in someone else’s eye while there may be a log in my own eye, I decided not to dwell on the malicious murder of 21 crows.

At the road department, I asked, “What do you do with the road kill, sir?”

“We eat it!” he said.

“Mainly raccoons and ‘possums,” I joked. “Well, sir, if you’ll have someone remove those birds from the roadside, next time I see you I won’t ask you to eat crow!”

February 8, 2016

The Green Commode in the Valley

Behind the “No Dumping” sign shot up with bullet holes, the downhill slope offers up weird findings. They don’t show up all at once, much less by categories, but let me classify some of the more intriguing types.

Behind the “No Dumping” sign shot up with bullet holes, the downhill slope offers up weird findings. They don’t show up all at once, much less by categories, but let me classify some of the more intriguing types.

First, the automotives: I see something not quite shiny, but definitely metallic. A wiggle and a tug, and up comes a rusty old muffler. Something round looks like the bottom of a bottle but, pulled up, reveals itself as a carburetor. Sunlight gleams off an object in the leaves— a chrome steering wheel. Windshield wipers go into my trash bag, along with a big old truck radio.

Next, abandoned apparel: A tee-shirt, men’s colored briefs, women’s lingerie; a single flip-flop sandal here or there, a solo jogging shoe, and more of the same in other places though never matching, never in pairs; one sturdy-looking hiking boot, plus another boot sole and heel without the upper.

Next, abandoned apparel: A tee-shirt, men’s colored briefs, women’s lingerie; a single flip-flop sandal here or there, a solo jogging shoe, and more of the same in other places though never matching, never in pairs; one sturdy-looking hiking boot, plus another boot sole and heel without the upper.

Someone thought the forest animals might find a long cell phone charging cord useful. I discovered it neatly folded in an open box. I’m unconvinced that raccoons and ‘possums talk on the phone so I tossed the package into my trash bag.

I decline to roll the dozens of old tires up the steep incline. A television, its thick glass screen punched out, resists coming up from its semi-burial site. One of these days, I’ll haul up the tricycle wheel with pedals still attached. And so far, I’ve left a folded lawn chair and a number of rusting real estate for sale signs. I may get them when I bring a stronger bag, and perhaps a stronger friend.

Speaking of things left where I found them, did I mention the toilet? It’s still sitting on the valley floor, scarcely sheltered by scattered trees. I doubt anyone uses it. You can’t flush it. A purple skink slithered out of it when I took a look.

My friend Pam says this toilet will evolve into a planter growing ferns and moss. If so, someday someone will write a song about the green commode in the valley.

February 1, 2016

Big Deal!

“BIG DEAL!” Phyllis shouted. She was a gorgeous...

“BIG DEAL!” Phyllis shouted. She was a gorgeous blonde, a high school student who lived around the block and belonged to our church. As for me, I was a nine-year-old kid on his first-ever church retreat.

Phyllis was introducing the program, getting everyone’s attention with her sarcastic yell. The fact that I remember her shouting “BIG DEAL” nearly 60 years later is proof of how effective she was. “Big deal,” in the way Phyllis said it, means “who cares?” Her program, anticipating the 1960s, addressed the problem of apathy. Her goal was to get young people to care about the world where we live.

When you drive around the North Georgia Mountains (or wherever you live) and see roadsides littered with trash, do you say “big deal?” Or do you care?

One man says it ticks him off when people throw their lunchtime leftovers out the car window. He feels angry because he cares about how the area near his home looks. He gets mad because someone else doesn’t care if trash piles up along our roads.  He might even like to catch someone in the act of littering so he could pick up their trash and hand it back to them and say, “Excuse me, I saw you drop this. If you don’t want to keep it, please put it where it belongs.”

He might even like to catch someone in the act of littering so he could pick up their trash and hand it back to them and say, “Excuse me, I saw you drop this. If you don’t want to keep it, please put it where it belongs.”

Instead calling them an ugly name, he and his wife patrol a mile of a county road and pick up after those who just don’t care. The reward is the satisfaction of a better-looking stretch of land, and the knowledge that the resident wildlife will suffer less harm than when they’re confused by litter, which can threaten their health and safety. This man and his wife inspired my wife and me to follow their example.

I wish everyone cared as much as my friends who adopted a mile of the county road. I wish I knew how to make litterbugs care enough to change their ways. Rather than dwelling on those who don’t care, I’ve decided to pick up after them.

Every year during April, chambers of commerce promote the slogan, “Keep America Beautiful!” Merchants and realtors want their community to be charming. When our surroundings are covered with trash, our community isn’t a very scenic place to visit. Since tourism plays a key role our economy, so is a nice-looking environment.

Taking pride in the beauty of our mountain forests and neighborhoods is a big deal.